Last time I looked at the short but eventful life of Arthur Compton Ellis. He seemed to have a very good chess playing friend in George Tregaskis.

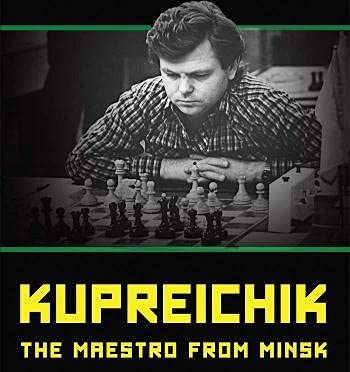

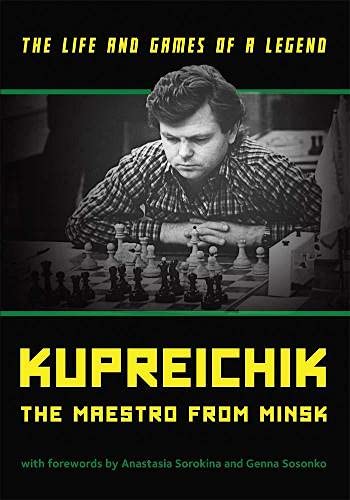

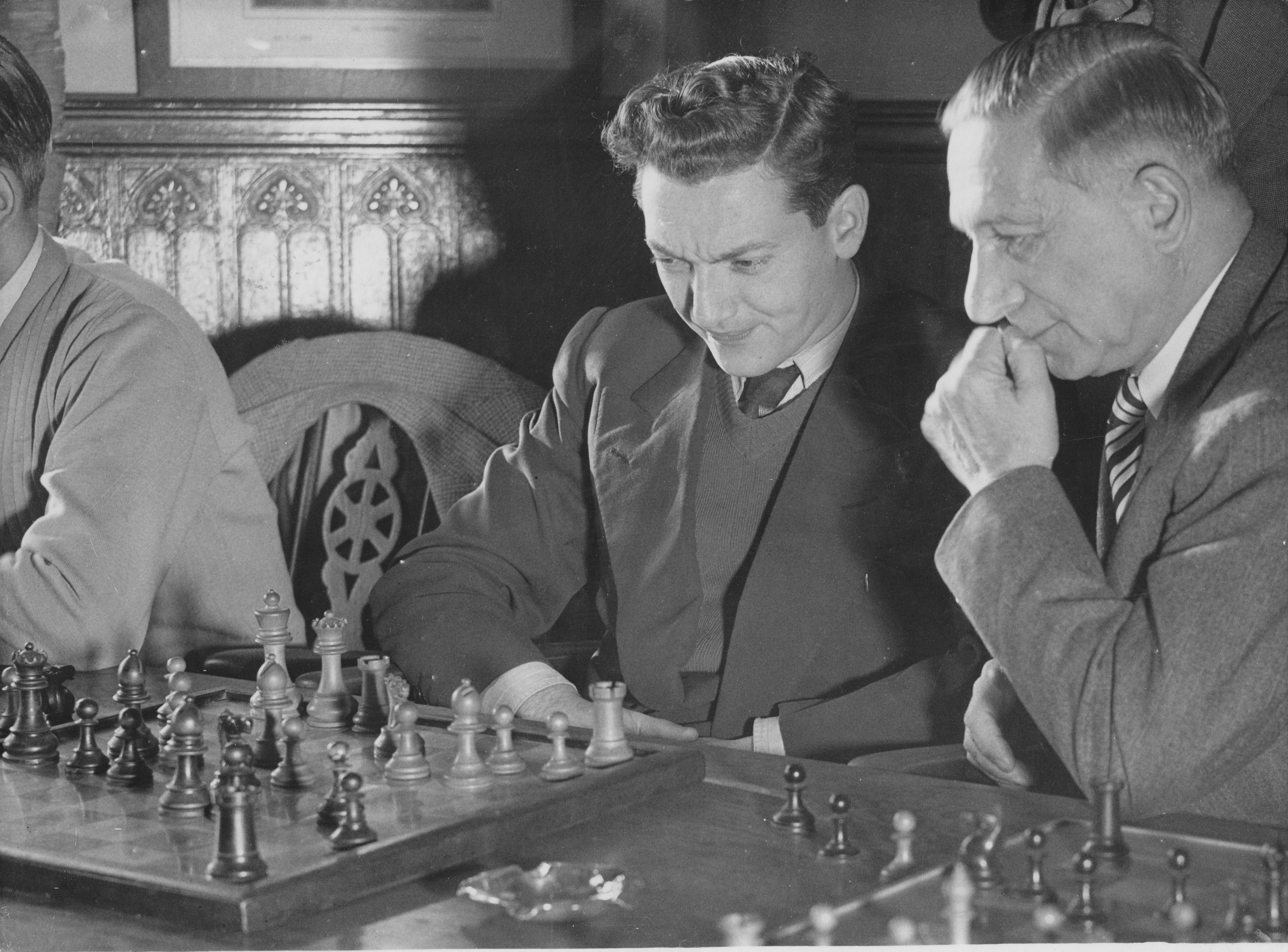

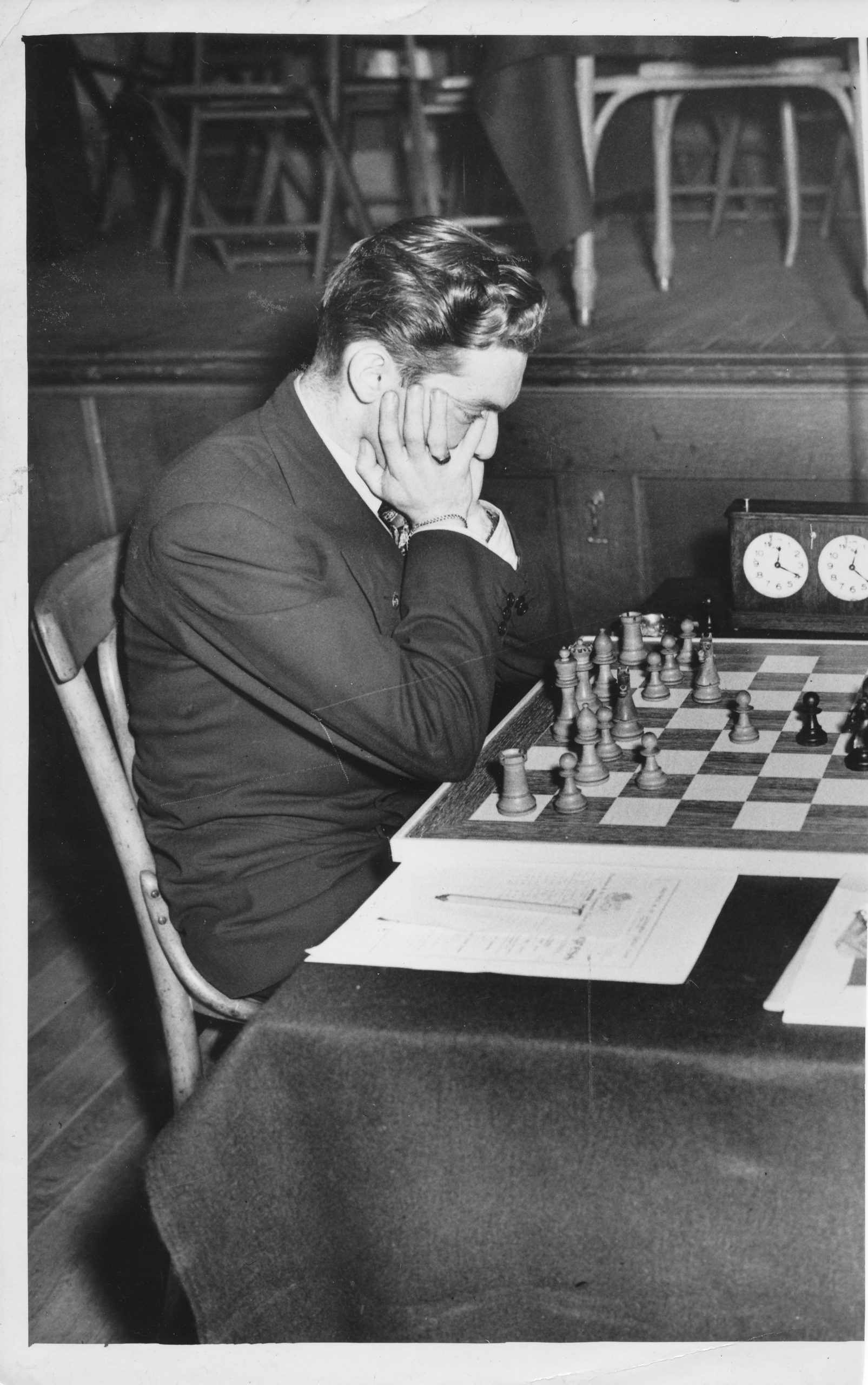

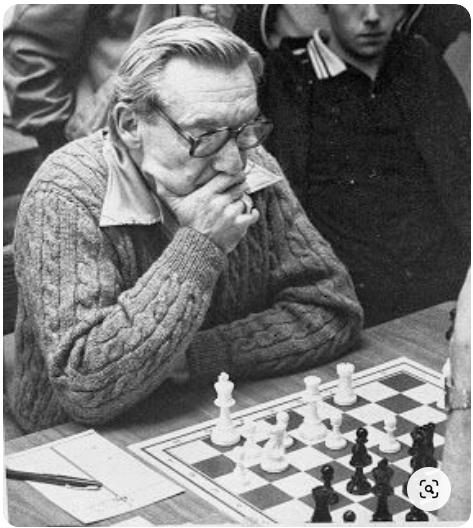

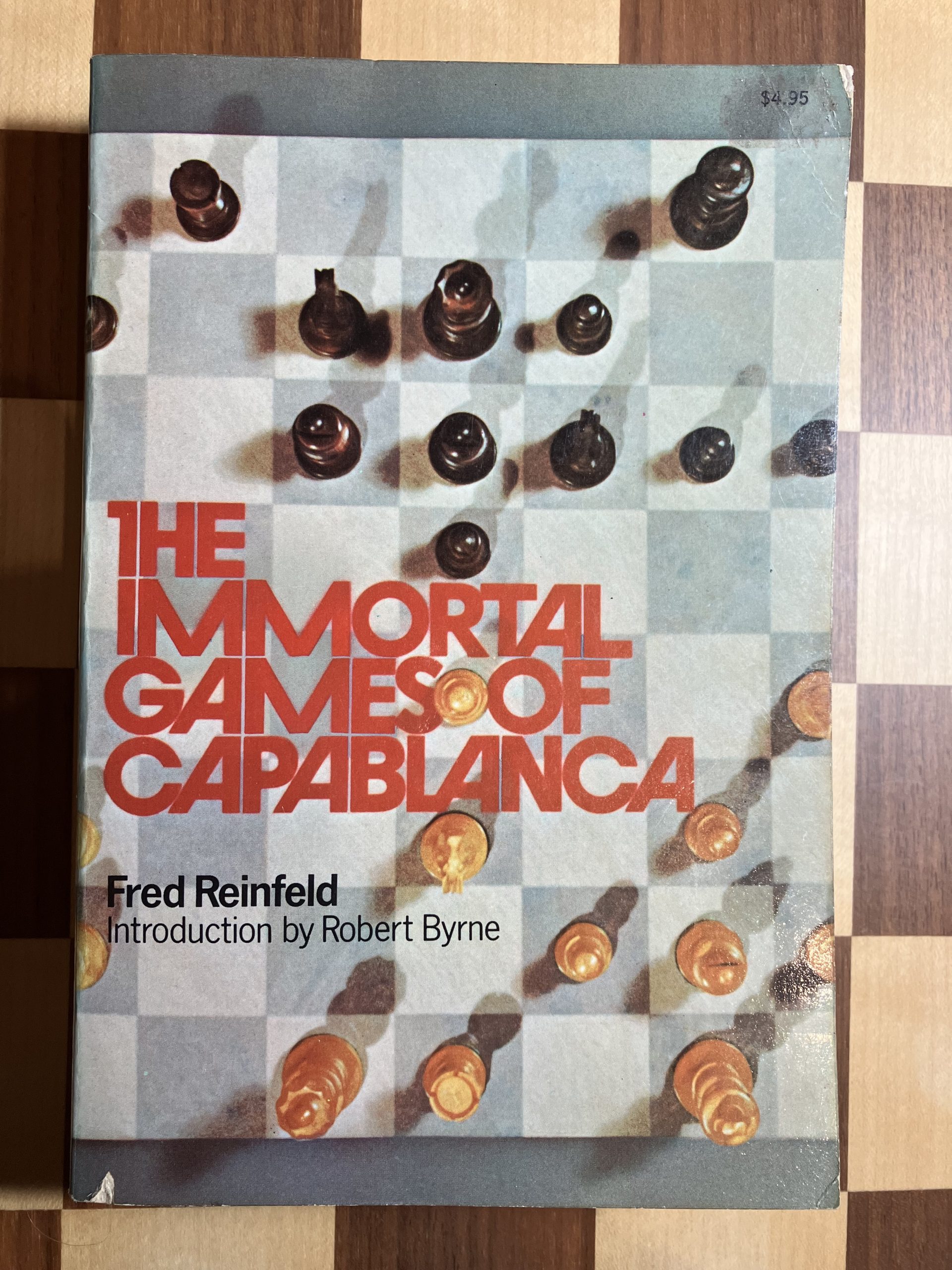

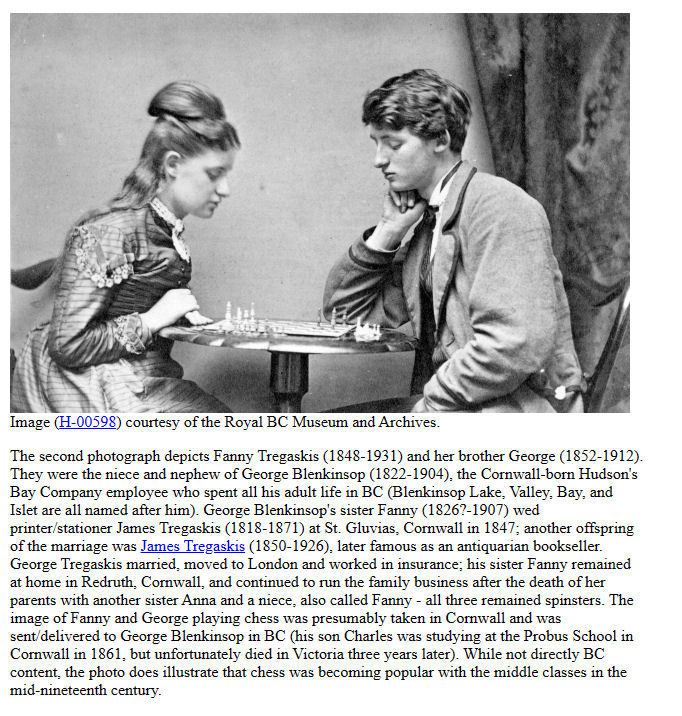

It’s time to find out more. Let’s start with this charming photograph, which, for rather obscure reasons, ended up in a museum collection in British Columbia.

As you might have guessed, the name Tregaskis is of Cornish origin, but George, the young man in this photograph, moved to London, finding work as a Fire Insurance Clerk. He married Annie Isabella Balfour in 1883, fathering four children, our George (born 18 February 1884), Oswald, Annie and, very much later, Frances.

We can pick him up in the 1901 census: the family is living at 36 Alderbrook Road, just south of Clapham Common, and George Junior, aged 17, has the same occupation as his father. Although George Senior doesn’t seem to have been a competitive chess player himself, he must have taught his children to play.

George Junior’s job would probably have involved gaining experience in different insurance offices in different parts of the country. We have a one-off mention of G Tregaskis playing for West Bridgford (Nottingham) in an away match against the Belgrave club of Leicester, where he won both his games on Board 4. This is quite likely to be our man, but we can’t be certain.

By 1911 he’d moved to Stoke on Trent, where the census found him living as a lodger with a widow, Lois Toft, and her 24 year old daughter Evangeline Maud. Everyone should have a daughter named Evangeline Maud. He joined the nearby Hanley Chess Club and, by October 1912, was chairing the county AGM. The 1912 edition of Kelly’s Directory tells us he was the District Superintendent, working for the Sun Insurance Office, 10 Pall Mall.

As you’ll have seen last time, his friend Arthur Compton Ellis (you’ll find three games played between them if you follow the above link) suddenly appeared in Stoke in early 1913. George and Arthur both played in a congress in Hastings, where George, in his first tournament, performed outstandingly well. Would this be the start of a glittering chess career?

You then saw that, in July 1913, the two friends suddenly left town: Arthur moved back to London, and then, tragically, to Oundle, while George’s work took him to Bristol.

He did, however, return to Stoke later in the year, when he tied the knot with his landlady’s daughter, Evangeline. It seems that his new mother-in-law joined him in Bristol, where the three of them set up house together.

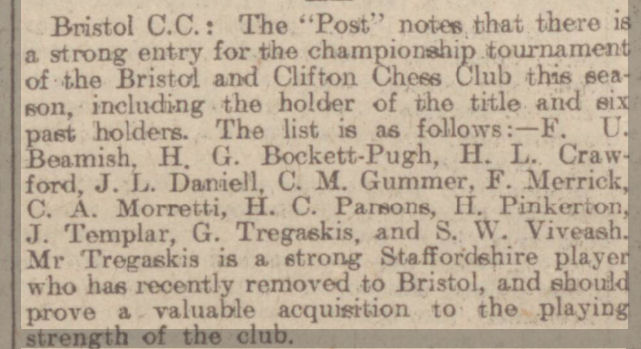

He didn’t waste much time joining the local chess club.

Observant readers will notice that the unfortunately initialled FU Beamish shared a surname with one of Arthur Compton Ellis’s opponents. You’ll find out more very soon.

The winner of this event was Scottish born Master Baker Henry Pinkerton, with George Tregaskis finishing in second place.

For a while chess in Bristol continued during the First World War, but there’s little mention of activity between 1915 and 1920.

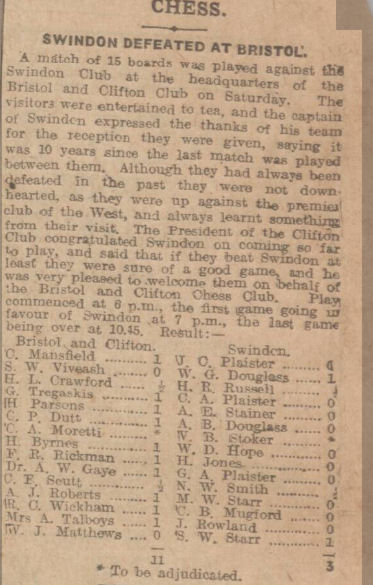

In December 1920 Bristol & Clifton played their first match against Swindon in a decade.

George had some interesting teammates. Comins Mansfield, on top board, was one of the leading chess problemists of the last century, and also a strong over-the-board player.

Agnes Augusta Talboys, down on board 14, was an artist whose paintings often involved her two passions, chess and cats. With any luck, she’ll be the subject of a future Minor Piece.

The 1921 census recorded George, Evangeline and Lois, along with a young general domestic servant, living at 21 Clyde Road, Bristol. George was working at the Sun Insurance Office as an Insurance Clerk, Evangeline was performing Home Duties, while Lois had no occupation. There would be no children of the marriage.

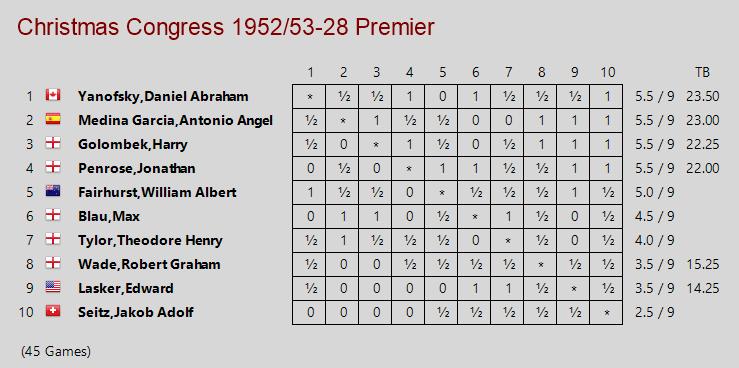

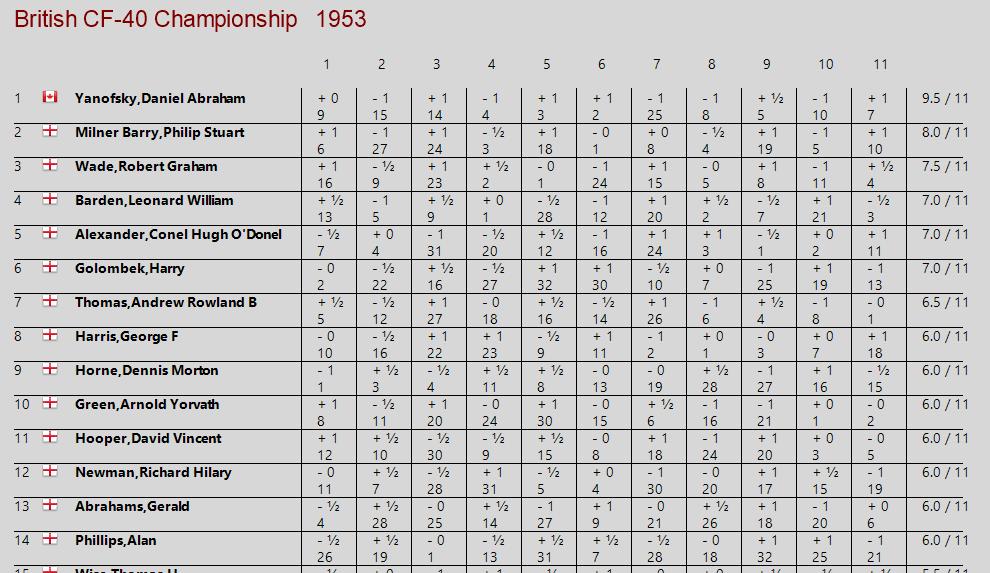

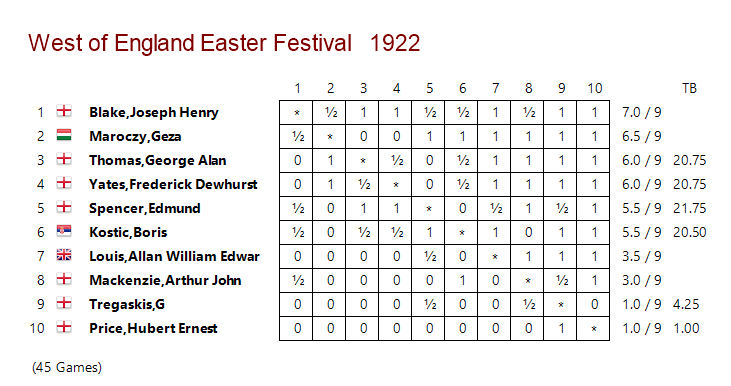

The following year, George Tregaskis, nine years after his tournament debut, finally had another opportunity to take part in a major event. As the champion of the West of England, he was invited to take part in the top section what would be the first of three biennial tournaments in the Somerset resort of Weston super Mare. International stars Geza Maroczy and Boris Kostic took on some of England’s leading players, headed by Sir George Thomas and Fred Yates.

The very unexpected winner, at the age of 63, was Joseph Henry Blake, as you’ll see below.

(Apologies to Fred Dewhirst Yates: ChessBase, annoyingly, still haven’t got his name right. It also cut off the last letter of Mr Louis’ third forename while seemingly being ignorant of our hero’s full name.)

You’ll also see that it didn’t go well for Tregaskis. In the very first round he provided the talented but erratic Hubert Price with his only win. In Round 2 he opened his account with a draw against Mackenzie, in a game which went into a second session.

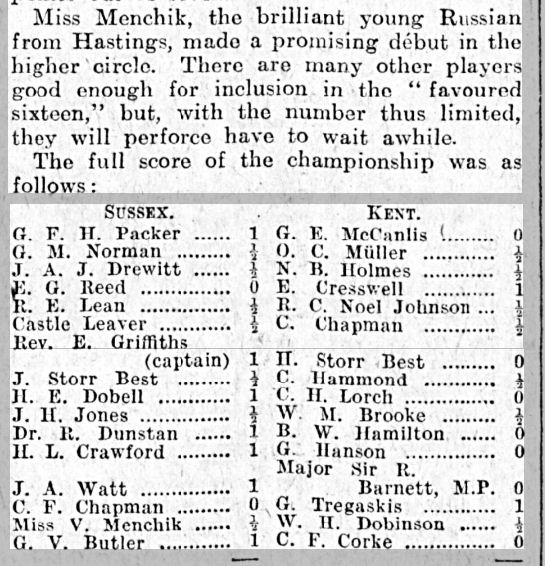

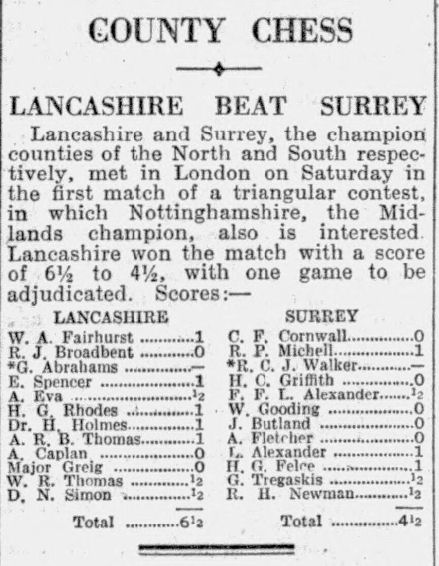

His third round game was also a long one.

Stockfish doesn’t think Mr Tregaskis ever had the upper hand, but you can judge for yourself. Click on any move for a pop-up window.

In the next round he faced Kostic, starting well enough, but, as so often happens when an amateur plays a master, he lost the thread in the middle game, after which his king fell victim to a snap attack, ending up uncomfortably on h4.

In Round 5 Tregaskis lost to Louis, but in the sixth round he managed to double his score with a draw against Spencer. The press reports suggest that his opponent missed a win.

Round 7 saw a heavy defeat against the eventual tournament winner, who played one of his pet opening variations.

In Round 8 George Tregaskis faced Yates, and managed to take him to a second session before capitulating. In the final round, despite having the white pieces against Maroczy, he lost quickly to a mating attack.

From the evidence of these games, it seems he was rather out of his depth against master standard opponents. Sometimes he went wrong in the opening, and, if he survived that part of the game he defended doggedly, but usually in vain.

Two years later he was back at Weston Super Mare, but this time relegated to the second section, billed as the ‘Minor Open’, where he managed 50% against strong amateur opposition. Max Euwe won the top section ahead of Sir George Thomas.

Later that year he left Bristol, moving to Kent, where he soon joined Bromley and Beckenham Chess Club as well as the Insurance Chess Club, and also represented Kent in county matches.

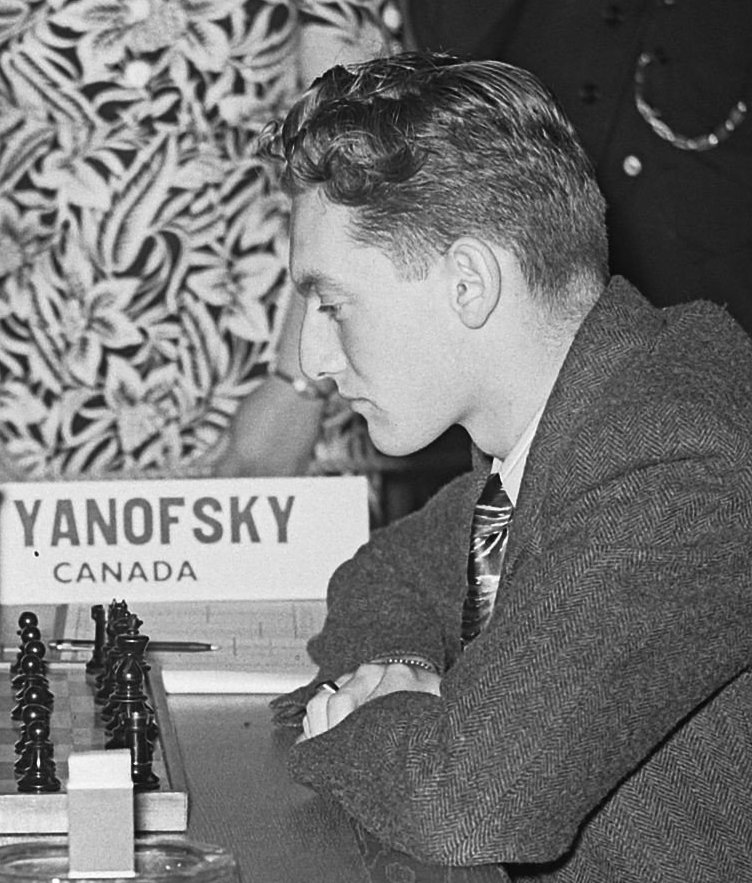

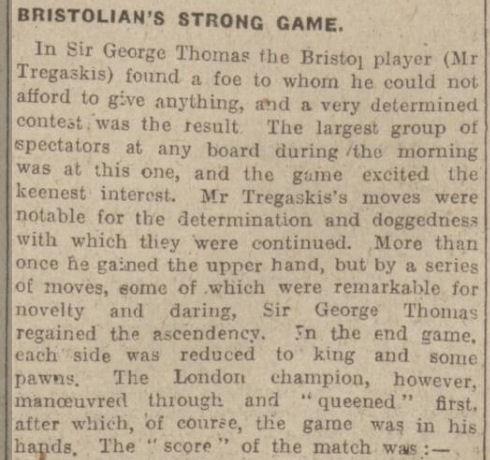

In this 1925 encounter on Hastings Pier he just missed playing a ‘brilliant young Russian from Hastings’.

Some interesting names on both sides, some of whom you’ll be meeting in future Minor Pieces.By 1928 the family had moved across South London to Sutton, where George, Evangeline and Lois were recorded as living in a house called The Crest in The Downsway, half way between the town centre and Royal Marsden Hospital, a tree-lined road of large detached houses: suburban living at its finest. As a result of this move he changed his county allegiance from Kent to Surrey.

In this match, played at St Bride’s Institute, a venue all London players of my generation will remember well, he helped his new county to an overwhelming victory.

In this match from 1930, Surrey were defeated by their northern rivals from Lancashire.

You can find out more about the Lanacshire boards 8 and 11 here. You’ll also spot Cecil Frank Cornwall: in those days it was the custom that county champions automatically played on top board.

George Tregaskis was also playing for Battersea at this time, although he lived some way away. Perhaps it was convenient for him to drop in on his way home from work.

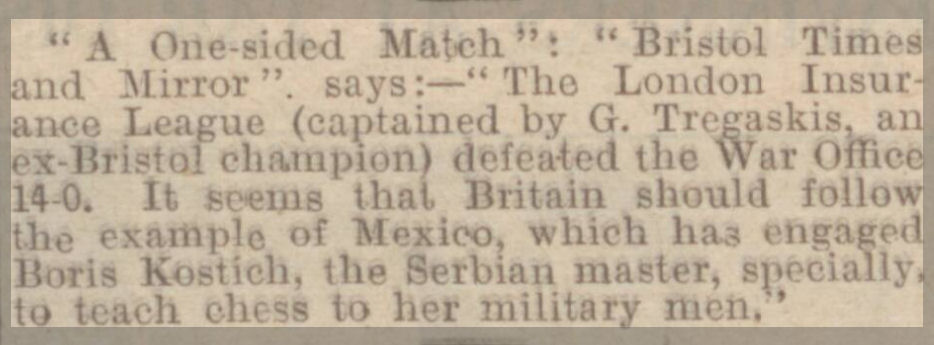

Here he is, captaining the Insurance Chess Club in a one-sided match against the War Office.

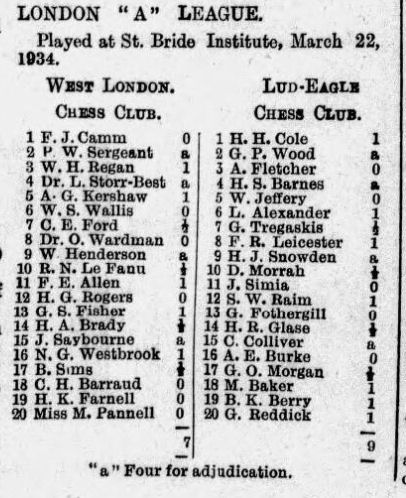

George also played for Lud-Eagle in the London League.

I’m guessing Board 13 was Percival Guy Laugharne Fothergill, who, as we’ve seen, appeared to compose as PGLF and play as G Fothergill.

You’ll see that the match was undecided due to that quaint old-fashioned concept of adjudication. Oh, wait a minute…!

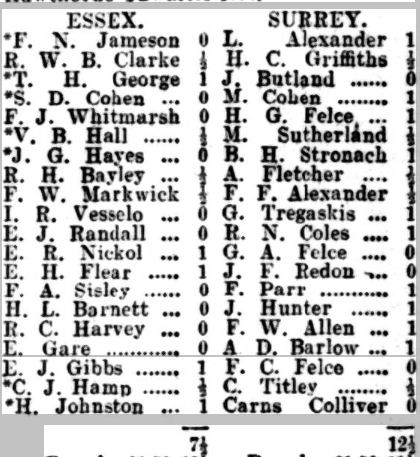

He had an interesting opponent in this 1935 county match against Essex.

(Isaac) Reginald Vesselo would go on to found the Chess Education Society. (He appeared on my Twitter timeline the other day as an attendee at the Ximenes 1000 Crossword Dinner: the 1st prize for that crossword was won by chess sponsor, problemist and banker Sir Jeremy Morse.) The Essex board two, Richard ‘Otto’ Clarke, would go on to devise the BCF Grading System. We’re now getting towards my time: many of my contemporaries would have known and played Frank Parr. I played both Nevil Coles and Jack Redon (whom I knew very well, but that’s another story for another Minor Piece.)

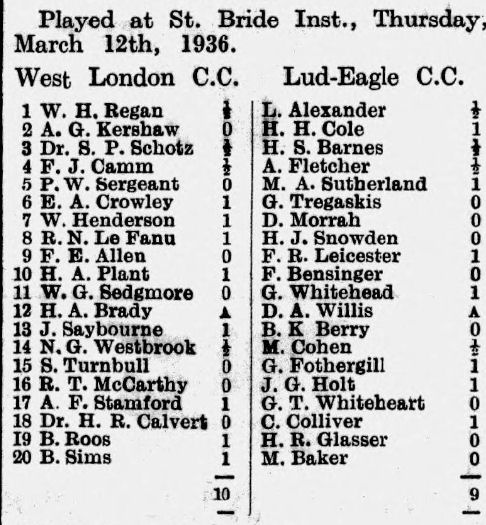

In this 1936 London League match he was up against an even more interesting, and perhaps rather disturbing, opponent.

Yes, this was indeed Aleister Crowley, ‘wickedest man in the world’ and star of The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict. One wonders whether George enjoyed the post mortem.

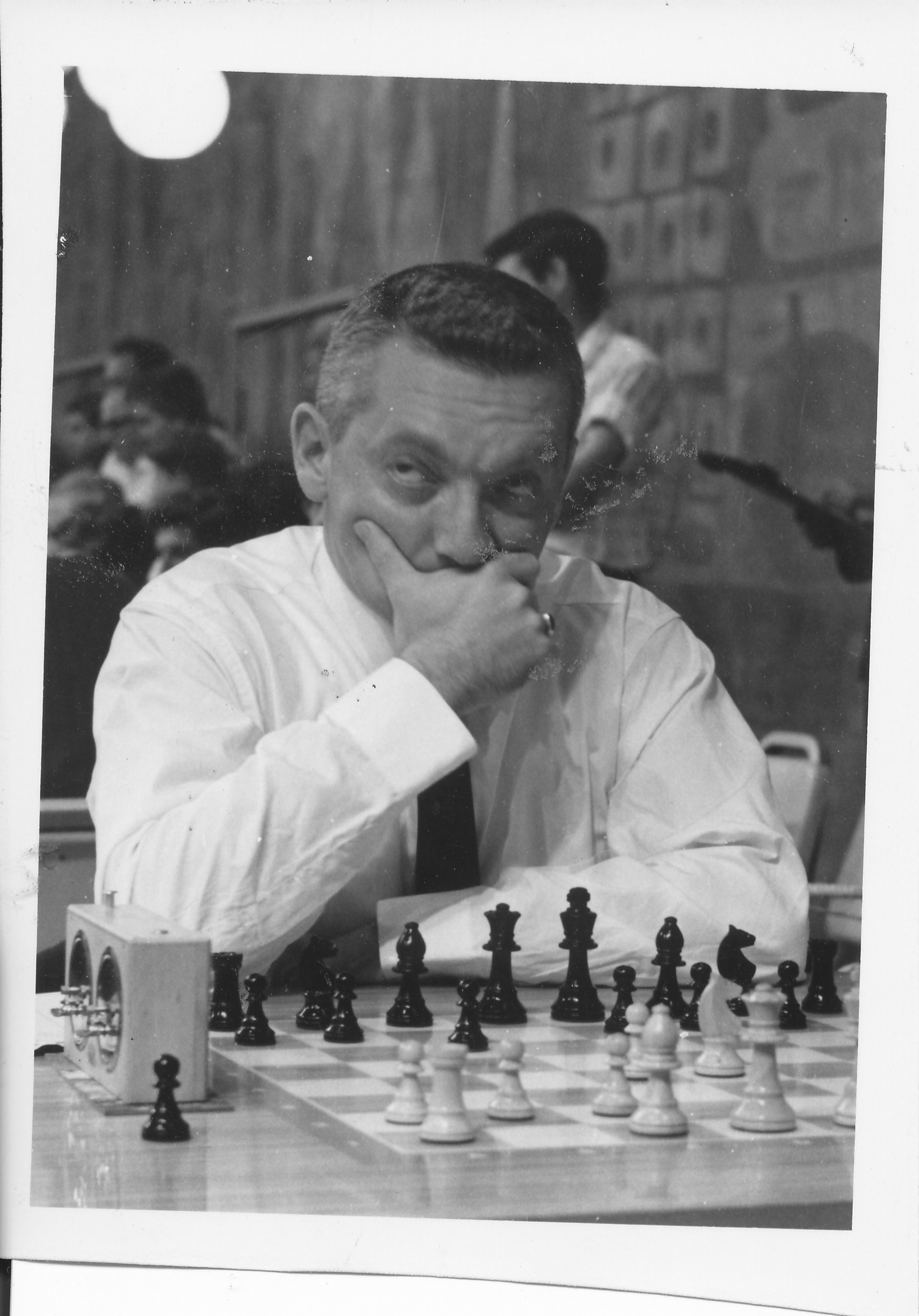

He continued playing up until the outbreak of World War II, taking 6th place behind Harry Golombek in the 1939 Surrey Championship.

At this point George, his wife and mother-in-law, moved down to Hove. Did his job take them there, or did they consider it prudent, with war imminent, to leave London? In the 1939 Register their address is given as 87 Hove Park Road, and his job is still an Insurance Superintendent. Although there was some chess being played in Sussex during the war, he seems to have decided it was time to hang up his pawns.

Lois Toft died on 6 December 1945, leaving only £141 15s 4d, with probate granted to her daughter. George died on 12 September 1959, leaving £3122 15s 5d. His address was given as 15 The Droveway, Hove, parallel to and immediately north of Hove Park Road. Evangeline moved to Goring-by-Sea, near Worthing, dying four years later, on 18 September 1963, and leaving £11143 14s.

Although he never fulfilled the promise of his first tournament appearance, George Tregaskis was a strong club and county player (EdoChess considers him about 2000 strength) who contributed much to chess, as an administrator as well as over the board, for almost 30 years. He deserves to be remembered.

There’s one nagging question, though. I still wonder about his relationship with Arthur Compton Ellis. Were they any more than just close friends? Was his marriage to Evangeline motivated by friendship rather than passion? Would this explain why his mother-in-law always lived with them? I don’t know: perhaps I’m reading too much into it, but perhaps he was hiding a story very similar to that hidden by his Lud-Eagle teammate Henry Holwell Cole. At some point there may well be more about him in another Minor Piece.

Sources and acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Google Maps

chessgames.com

English Chess Forum

EdoChess

ChessBase/Stockfish 15.1

Hastings Chess Club website