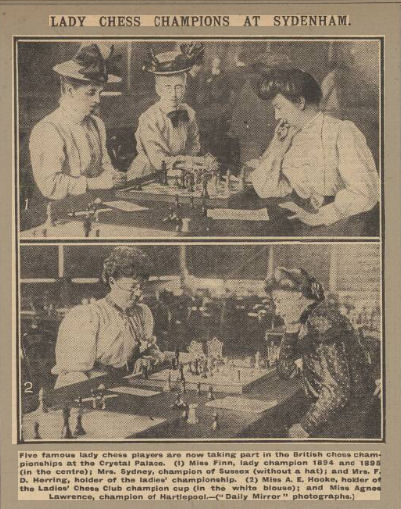

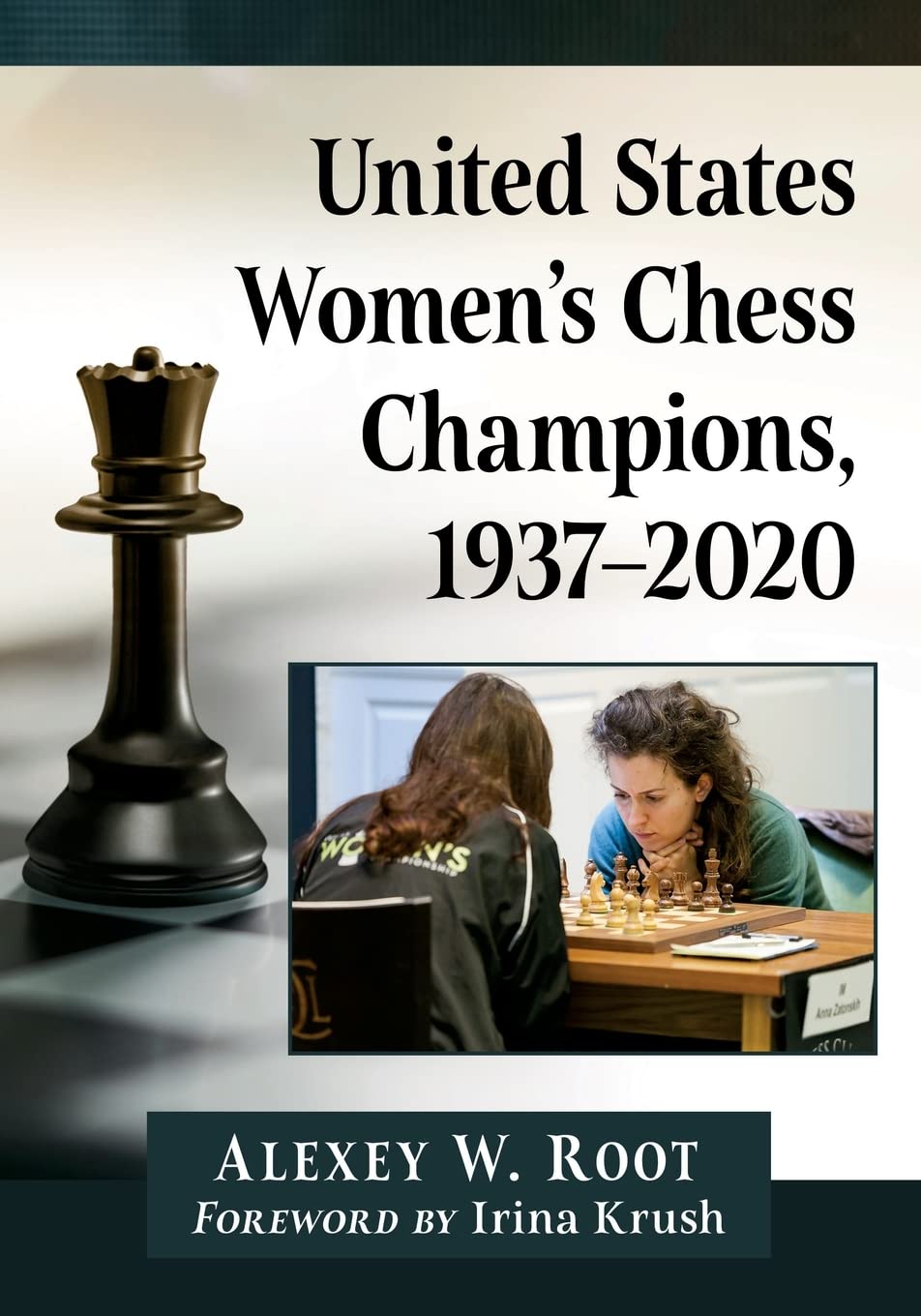

Last time we left Alice Elizabeth Hooke in 1914, on the outbreak of the First World War, a member of the London Ladies’ Chess Club and a competitor in the British Ladies’ Championships. She was unmarried, living in Cobham, and working as a Civil Servant for the Post Office Savings Bank near Olympia.

It would have been understandable if she had retired from chess at that point, but in the following decade she made a comeback. And what a comeback it was.

Our first post-war reference is in the 1921 British Championships, where she played in the Second Class A tournament, scoring 4½/11. I presume she wasn’t selected for the British Ladies’ Championship that year. Not having played for some years, and now in her late 50s, perhaps the selectors had good reason.

By 1922 Alice had moved from Cobham to Barnes, much more convenient for her job in Kensington, I suppose. Again, that year’s British Championship saw her competing in the Second Class A tournament, only managing 3/11.

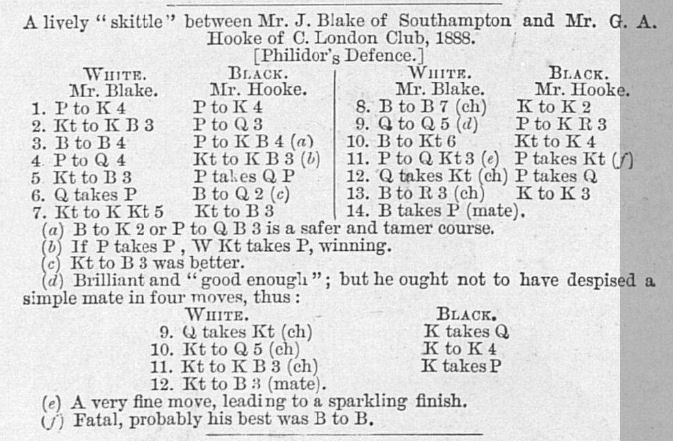

On 27 October 1923 the Cheltenham Chronicle published this position, which, they claimed, won a brilliancy prize in that year’s British Championship. I think they made a mistake: there’s no evidence that Alice played in the British that year, and in any case the subsidiary tournaments were run in a different way. So this game must have been played the previous year, where one of her three wins was against Arthur William Daniel, better known as one of England’s leading problemists of his day. As always, click on any move for a pop-up window.

The pension age for both men and women was reduced from 70 to 65 in 1925, so it’s possible Alice was still working at this point.

Here, from about 1924, is a Ledger Room in Blythe House. I’d imagine Alice was in a more senior role: perhaps, with her undoubted administrative skills, she was supervising the ladies in this picture.

Rather unexpectedly, she moved out of London again at about this point, this time up to Abbots Langley, north of Watford: electoral rolls for the period give her address as The Bungalow, Tanners Hill. If she was still working in London this would have been quite a long commute for her.

By 1925 she was back at the British Championships, this time selected for the British Ladies’ Championship for the first time since 1914. Her score of 4½/11 was very similar to her previous scores in the event.

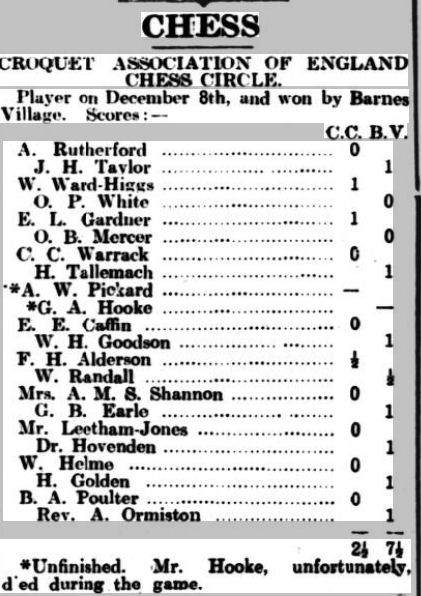

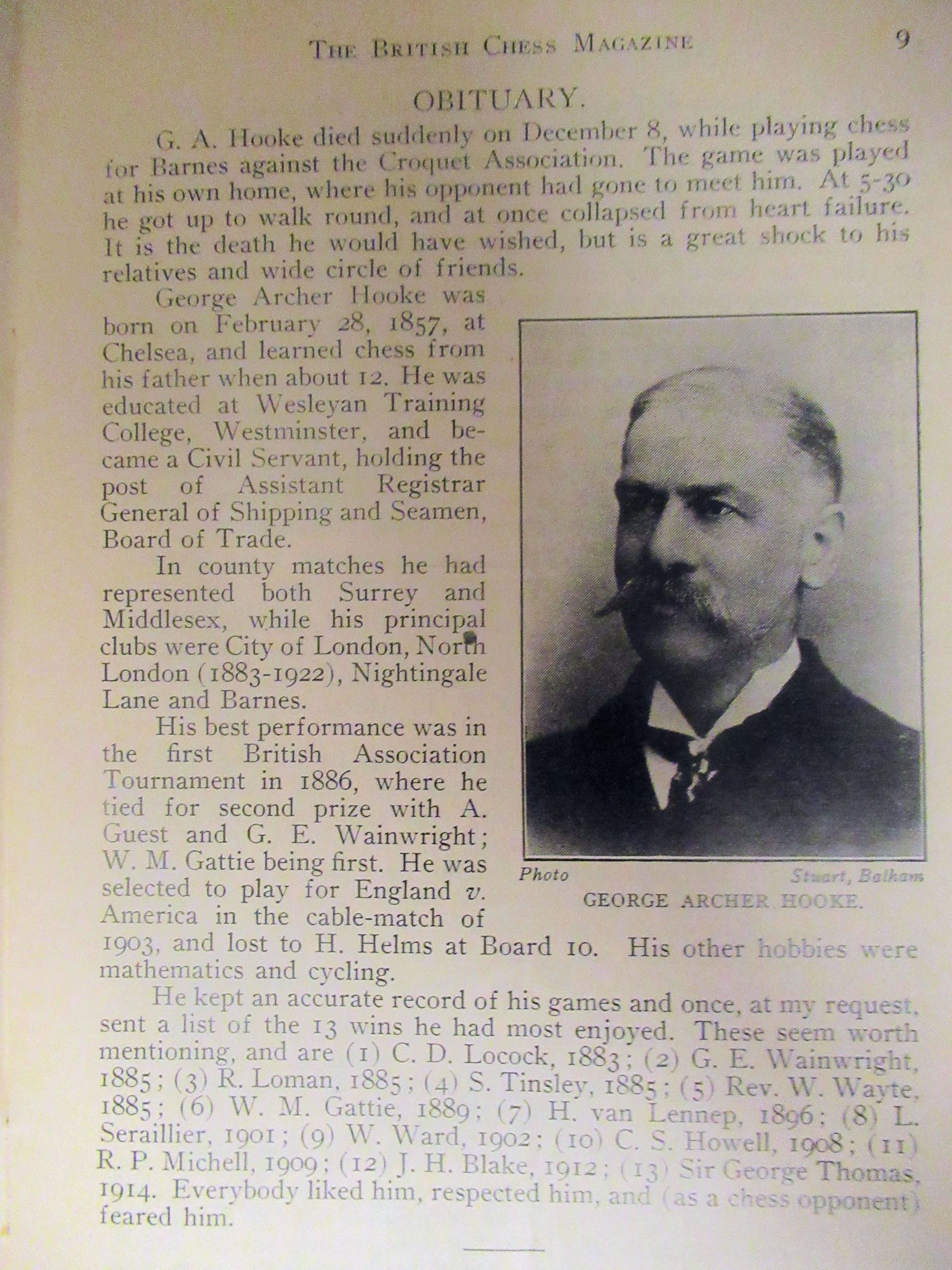

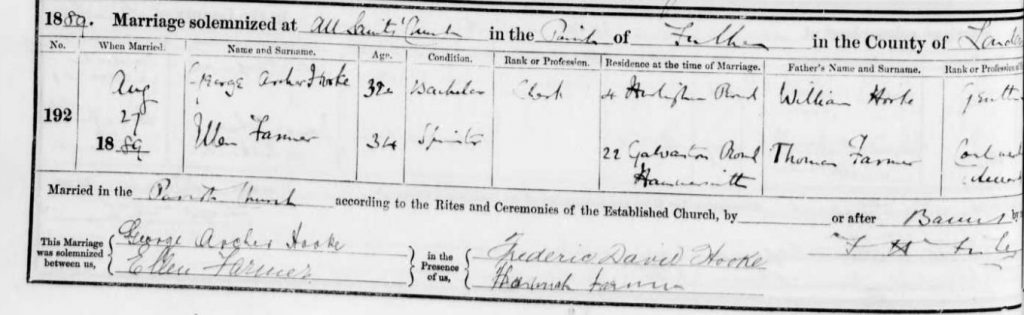

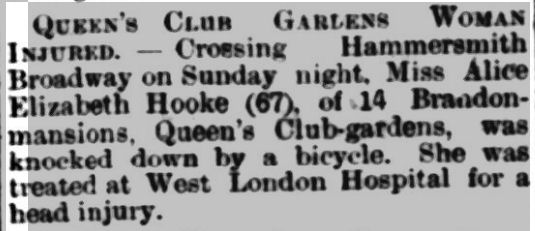

In 1928 Alice Elizabeth Hooke moved back to London, settling at 14 Brandon Mansions, Queens Club Gardens, W14, a mansion flat on the borders of Fulham and West Kensington, a mile or so from Blythe House (was she still working there?) and within easy reach of Hammersmith Bridge, where a bus would take her to visit her beloved brother George, whose wife would sadly die that year.

The British Championships that year took place in Tenby, and she made the journey to Pembrokeshire, where she more than surpassed her previous performances. She’d always finished mid-table in the past, but this time she finished in 3rd place with a score of 7/11 (including a win by default), behind Edith Charlotte Price and Agnes Bradley (Lawson) Stevenson.

This game, against the tournament winner, doesn’t show her in the best light. Alice chose a dubious plan in the opening and then made a tactical oversight, losing rather horribly.

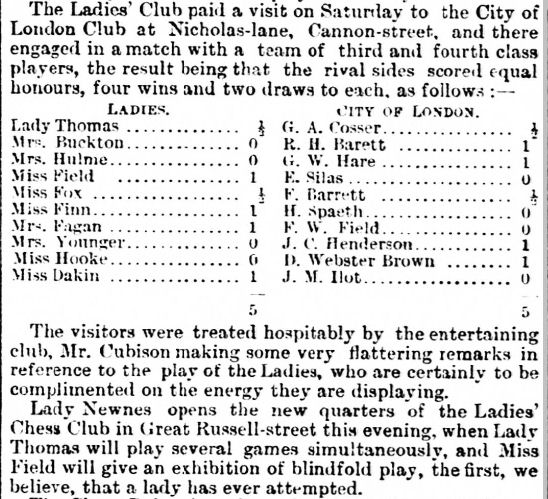

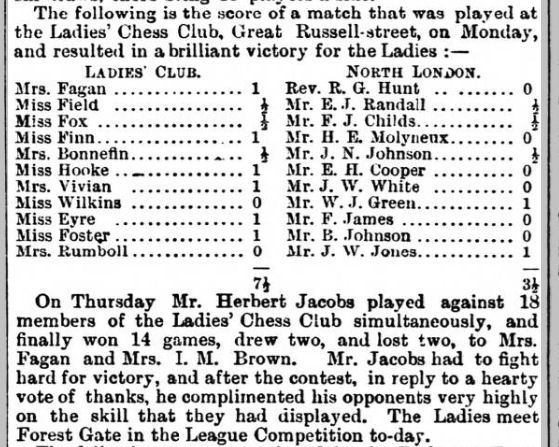

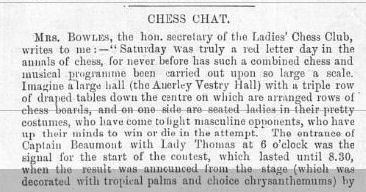

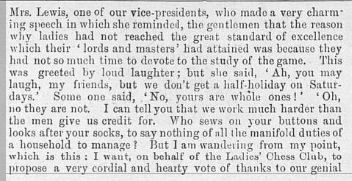

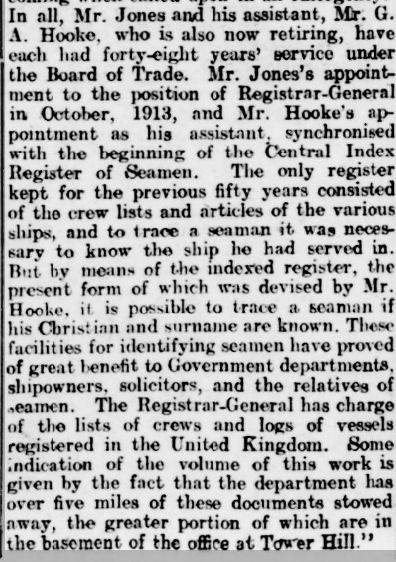

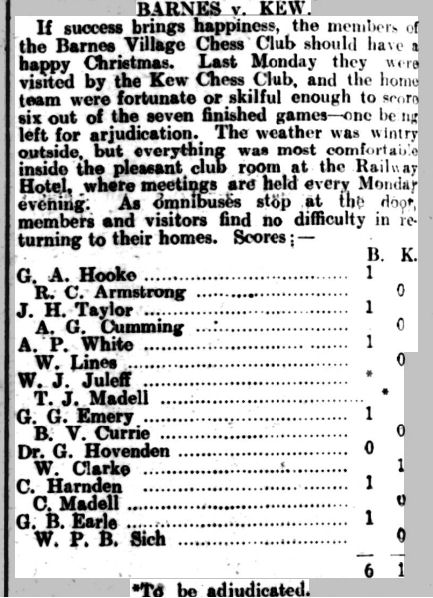

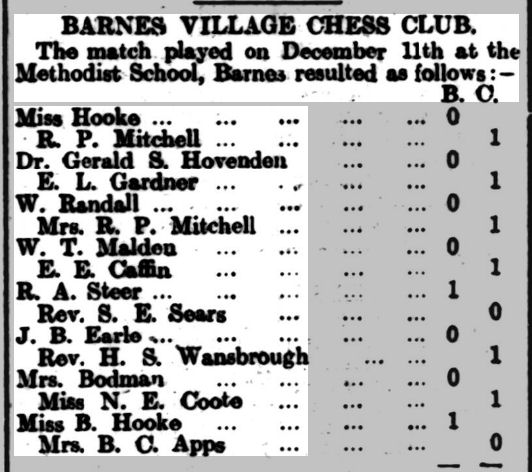

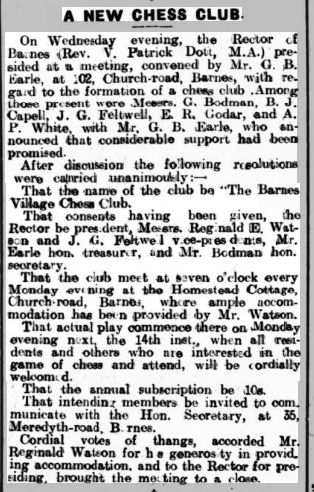

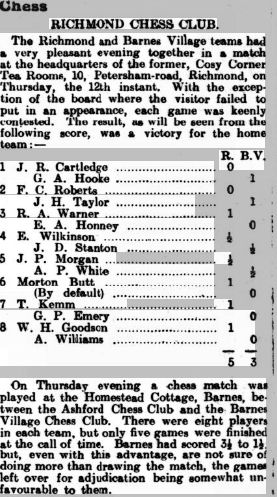

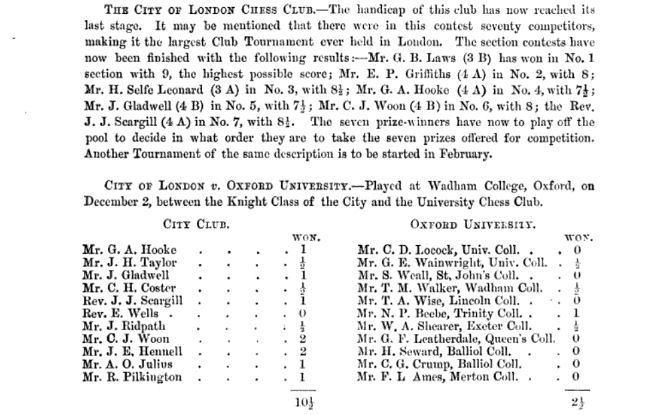

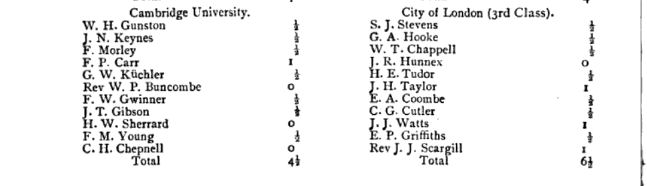

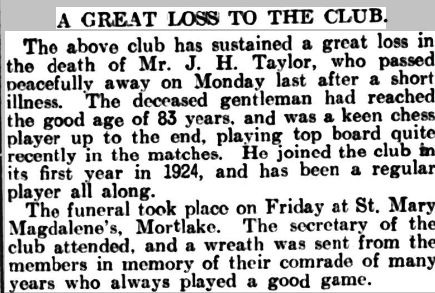

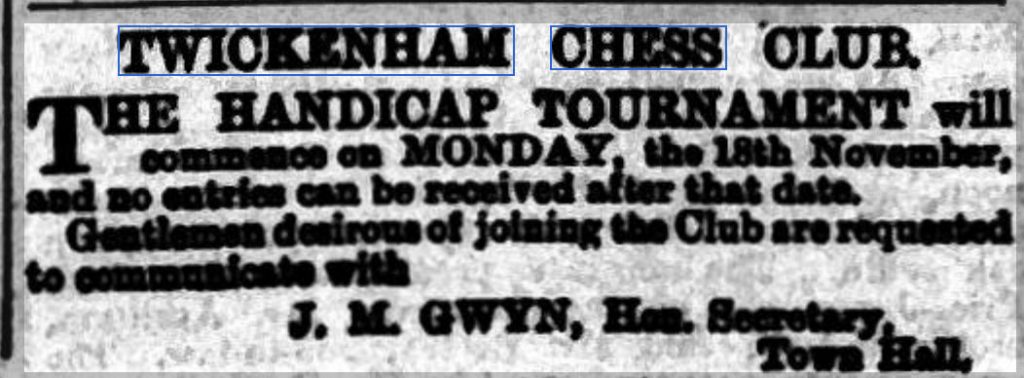

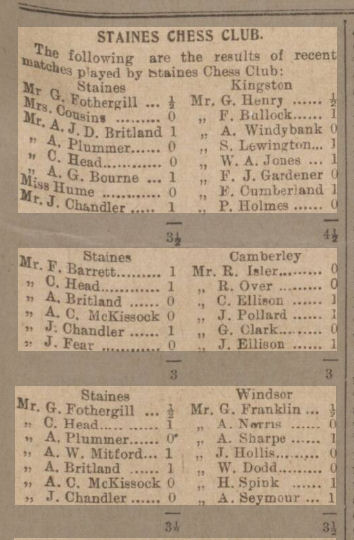

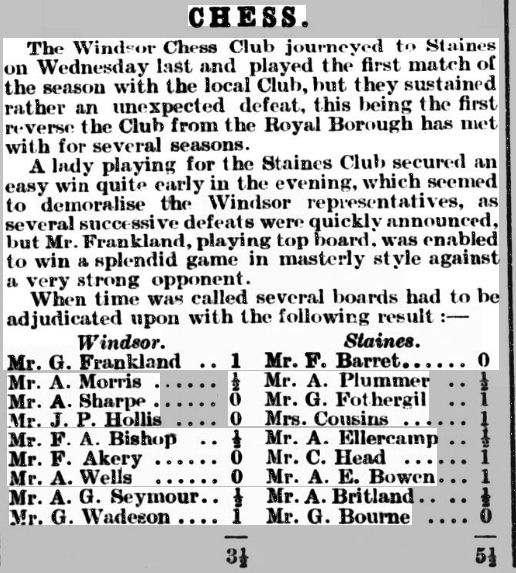

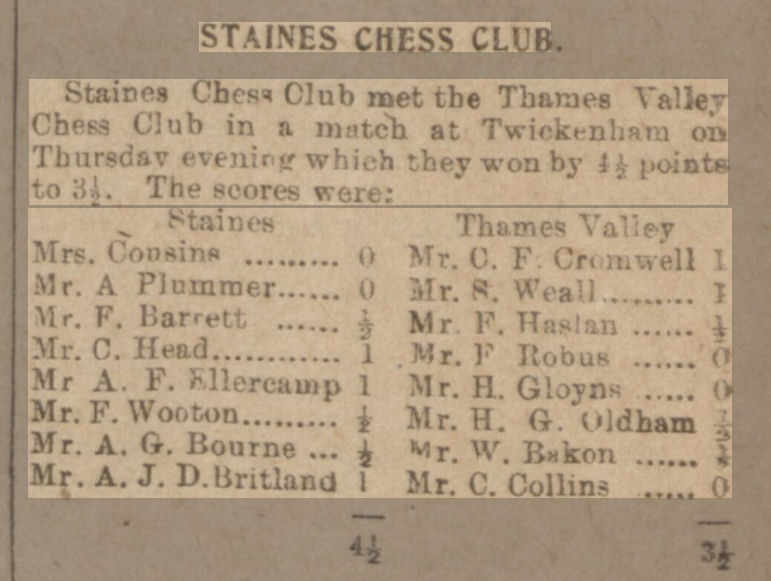

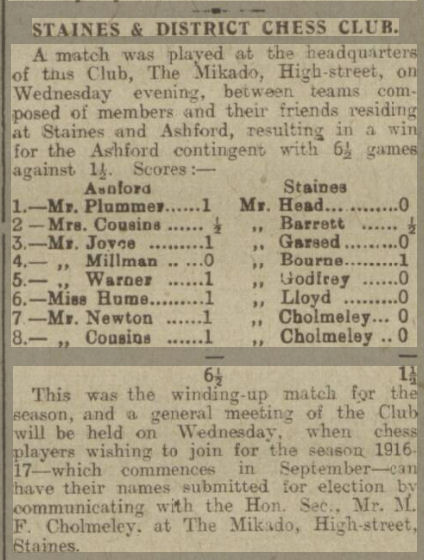

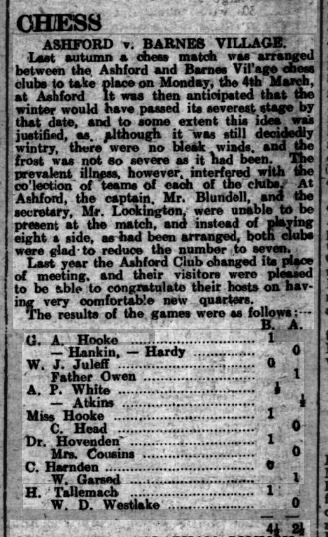

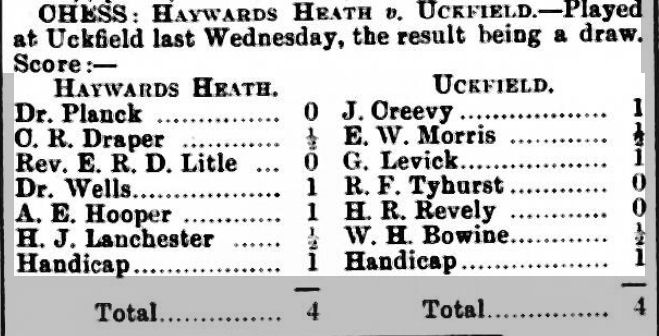

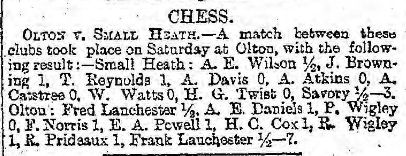

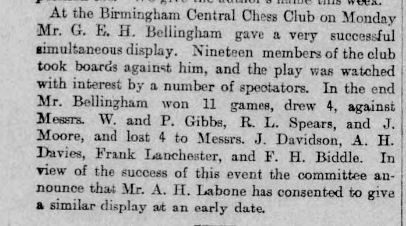

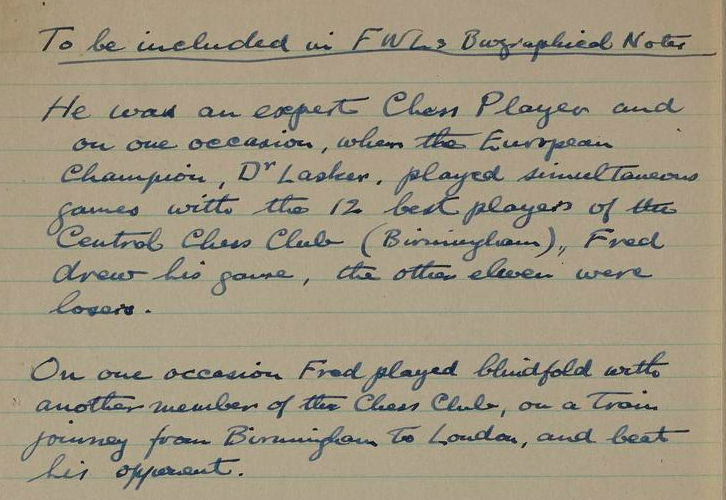

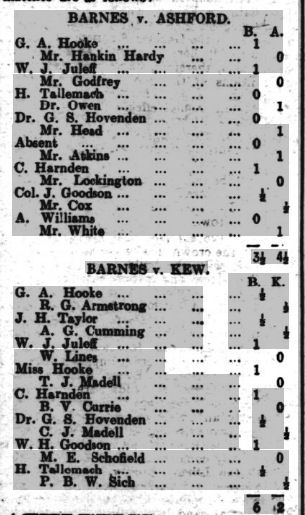

At this point her chess career really took off. She joined Barnes Village Chess Club and, probably for the first time since the demise of the Ladies’ Chess Club, started playing regularly in club matches. You might have seen this before.

Barnes Village wasn’t the only club she joined. She also, rather improbably, joined Lewisham Chess Club over in South East London, playing for them in the London League and for Metropolitan Kent in a competition against other parts of the county. They had several female members, most notably the aforementioned Agnes Bradley Stevenson, who lived in Clapham and was married to the Kent born organiser Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson: perhaps it was she who encouraged her friends to join Lewisham.

You’ll have seen a photograph of Alice playing Agnes Lawson, as she then was, in the previous article.

In 1929, now very much involved in Kent chess, she took part in their Easter congress, playing in the First Class A section. She also played in the British Ladies’ Championship again, which took place in Ramsgate that year, but found herself back in the middle of the pack, with a score of 5/11.

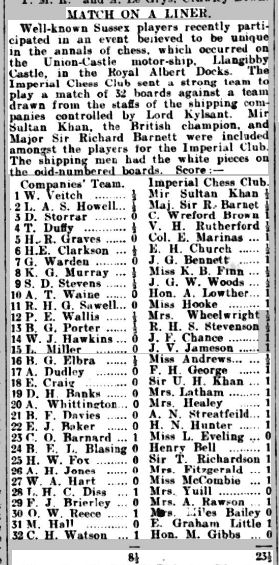

In June 1930 Alice took part in an event which attracted a lot of press attention: a chess match on a liner.

There she was, playing in the same team as Sultan Khan and other notables from various fields, one of thirteen ladies in the 32-player team (Board 32 was Mildred Gibbs). There, you’ll see, was Kate Finn, one of the F squad from the London Ladies’ Chess Club, from whom little had been heard since World War One. Although Agnes Stevenson wasn’t playing, her husband was there on board 13. There’s a lot more to say about this match: I’ll return to it in a later Minor Piece.

You can see Alice seated second from the right in this photograph of the event.

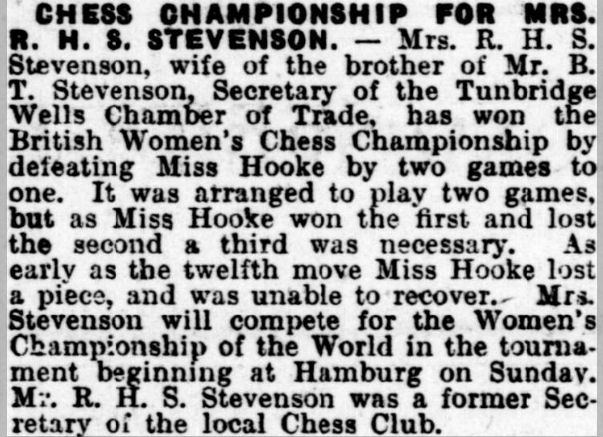

The British Ladies’ Championship in 1930 required a trip to Scarborough, and it was there that Alice Elizabeth Hooke scored what would be one of her greatest successes. She shared first place with Agnes Stevenson with a score of 8½/11. Although she lost the play-off it seemed that, now in her late 60s, Alice was in the form of her life.

The following month the news wasn’t so good, as Alice was involved in an accident requiring hospital treatment.

I can sympathise: Hammersmith Broadway has never been the easiest place to cross the road. Fortunately, she made a full recovery.

In 1931 in Worcester, Alice was less successful at the British Ladies’ Championship, but her score of 6½/11 was very respectable and sufficed for 5th place.

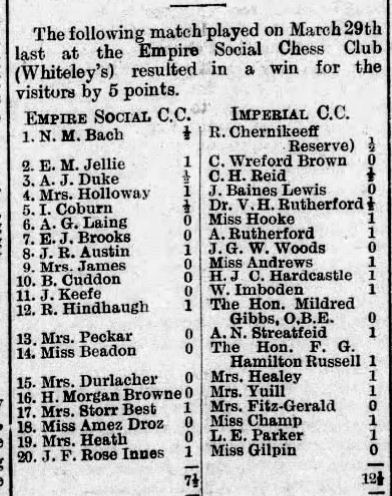

She didn’t have to travel far for the 1932 British Ladies’ Championship, which took place at Whiteley’s department store in Bayswater, which also hosted the Empire Social Chess Club. Perhaps the home advantage helped as she repeated her 1930 success, sharing first place this time with Kingston’s Edith Mary Ann Michell and her old rival Agnes Bradley Stevenson. Her loss to tailender Jeanie Brockett, from Glasgow, who had also beaten her last year, cost her the title.

BritBase reports on the play-off:

The first game, played at the Empire Social Chess Club, Bayswater, London, on Thursday 8 September 1932, was a win for Agnes Stevenson against Edith Michell. Subsequent games had to await the return of Alice Hooke from holiday. Two games were played during the week 19-25 September in which Stevenson and Michell both won games from Hooke and Michell won her return game with Stevenson. Scores at that stage: Michell, Stevenson 2/3, Hooke 0/2. Then according to the Times, 3 October 1932, the following Tuesday (27 September) Michell beat Hooke, but then Hooke won against Stevenson on the Thursday (29 September) making the scores Michell 3/4, Stevenson 2/4 and Hooke 1/4. The text in the Times was as follows: “The match to decide the tie for the British Ladies’ Championship has ended in a win for Mrs. R. P. Michell, who defeated Miss Hooke on Tuesday last. There was a possibility of another tie between Mrs. Michell and Mrs. Stevenson, but Miss Hooke put this out of the question by defeating Mrs. Stevenson on Thursday, and the final scores are:—Mrs. Michell 3 points, Mrs. Stevenson 2, and Miss Hooke 1.”

As she approached her 70th birthday, Alice Elizabeth Hooke seemed finally to have established herself as one of the country’s finest woman players (excluding, of course, Vera Menchik). The results from the pre-war years, where she was consistently in the lower middle reaches, must have been a distant memory. Perhaps the standard of play among the British Ladies had declined, but even so, reaching her peak at this time of her life was undoubtedly a remarkable achievement. In between playing in the tournament, she was also supervising social chess at the Imperial Club, which suggests that, even at that age, she wasn’t short of stamina. Well played, Alice!

It’s unfortunate that very few games from the British Ladies’ Championship in these years have survived: if you come across any of Alice Elizabeth Hooke’s games from these events, do get in touch.

This was to be her last great result, though. Her performances in the three subsequent years saw her back in mid-table positions (4/11 in 1933, 5½/11 in 1934 and 5/11 in 1935), and she also played without success in the First Class A section of the 1933 Folkestone Congress. Perhaps her age was finally catching up with her.

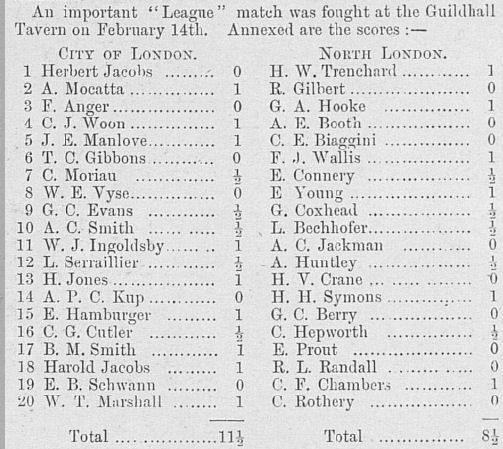

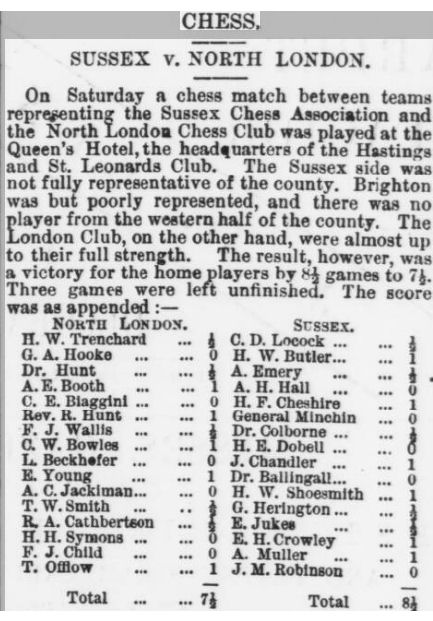

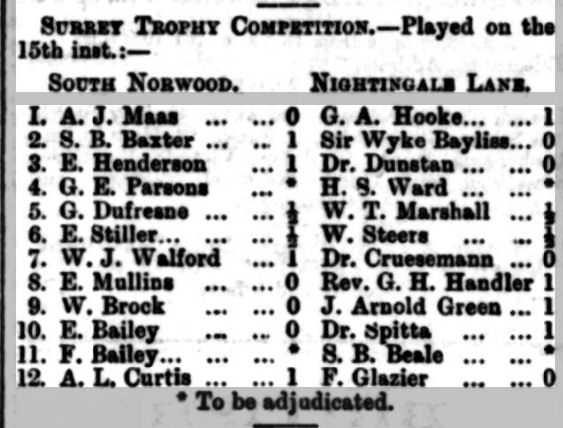

Thanks to Brian Denman for providing this game from a county match where Alice was outplayed by a very strong opponent. The top 20 boards of this match were an official county championship match, for which Mackenzie wasn’t eligible.

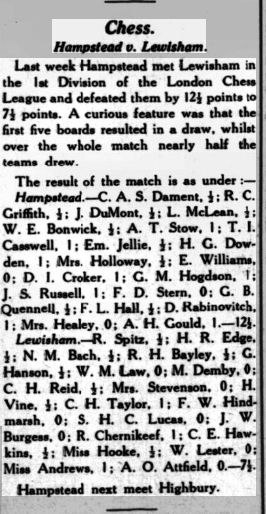

Here she is in 1932 playing for Lewisham in the London League with Mrs Stevenson & Miss Andrews against a strong Hampstead team including another of her regular rivals, Edith Martha Holloway. There are some interesting names on both sides, but for now I’ll just draw your attention to the Hampstead Board 7 Thomas Ivor Casswell (1902-1989). He was still playing for Hampstead in the London League 42 years later: I played him in 1974: the result was a draw. The golden thread that binds us all together.

The Imperial Chess Club, which ran between 1911 and the outbreak of World War 2, along with the shorter-lived and similarly named Empire Social Chess Club, in some respects, fulfilled the purpose the Ladies’ Chess Club had served before the First World War. The Imperial was open to ladies and gentlemen for mostly social chess, and was in part designed as a club for visitors from other parts of the British Empire, so it was understandable that Sultan Khan and his patron were members.

You will notice that there were eight ladies in each team of this twenty-board friendly match.

For more information about the Empire Social Chess Club I’d encourage you to read two fascinating articles by Martin Smith here and here.

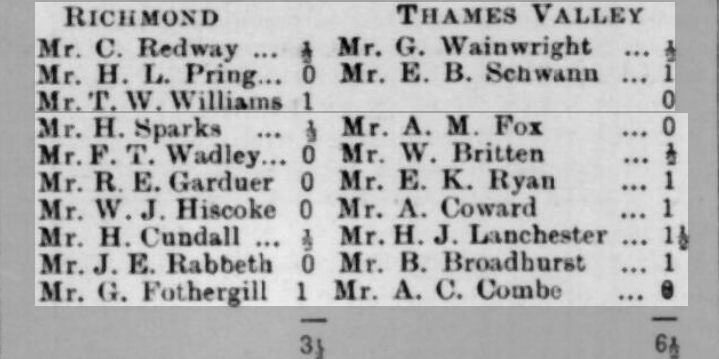

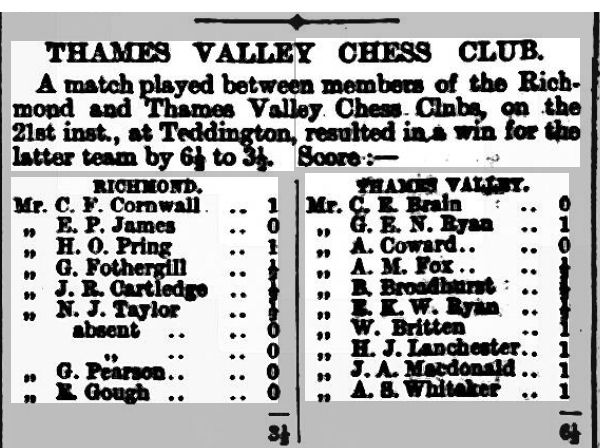

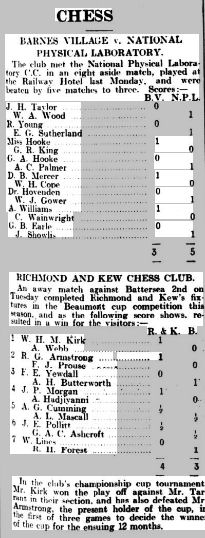

In this 1934 match against the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington she just missed playing metallurgist Edwin George Sutherland (1894-1968).

This was almost certainly the EG Sutherland I played in a 1966 Thames Valley League match between Richmond & Twickenham C and Kingston B. He beat me after I made a horrendous blunder all too typical of my early games in a better position. To the best of my knowledge, he’s also the earliest born of all my opponents in competitive games, whose dates of birth therefore range from the 19th to the 21st centuries.

There are some interesting names in the Beaumont Cup match between Richmond & Kew and Battersea 2: you’ll meet one or two of them in future Minor Pieces.

By the mid 1930s, and now into her 70s, Alice decided it was time to downsize. A new estate of Art Deco mansion flats, called Chiswick Village, had just been built near Kew Bridge, between the A4 and the Thames, which were smaller – and much cheaper – than those in the rather palatial Queen’s Club Gardens. Looking at them now, they’re still remarkably cheap for the area: I was almost tempted to sell off my chess library and buy one myself.

The Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society tells us here that Chiswick Village is the name of the development of four separate blocks containing 280 flats, built on land that was formerly orchards between Wellesley Road and the railway line. The flats, designed by Charles Evelyn Simmons and financed by the People’s Housing Corporation, were built in 1935-6. When the plans were displayed at the Royal Academy, the development was called Chiswick Court Gardens – a more appropriate name than ‘Chiswick Village’ with its connotations of a rural idyll. The 1937 edition of the official guide to Brentford and Chiswick, described Chiswick Village as ‘undoubtedly London’s most remarkable and praiseworthy housing venture’.

In the 1936 electoral roll she was ensconced in 13 Chiswick Village, one of the first occupants of this new development, and was still there, described as a retired civil servant, in 1939.

Although she was no longer taking part in the British Ladies’ Championship, Alice was still playing regularly for Barnes Village Chess Club, and still travelling to Kent where, in 1938, she lost to 12-year-old prodigy Elaine Saunders in the first round of the County Ladies’ Championship. Elaine was actually living in Twickenham at the time: her only Kent connection seems to be that it was her father’s county of birth.

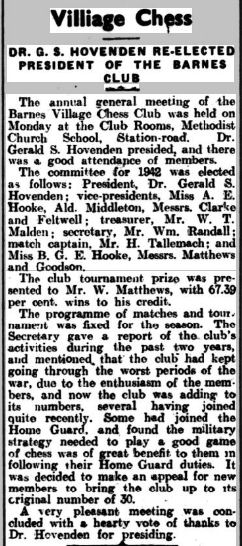

Barnes Village was the only club in the area keeping its doors open during the Second World War, and Alice was still, in old age, very much involved both as a player and a committee member.

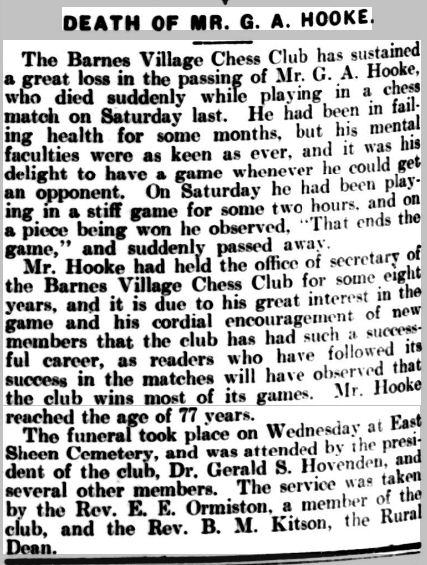

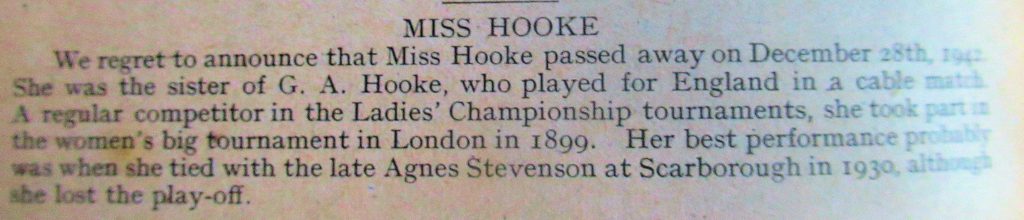

In 1942 she was elected a vice-president at their AGM, while her niece Beatrix was also on the committee. But this would be her last AGM as she died at the end of the year at the age of 80. The BCM, beset by wartime paper shortage, only gave her a six line obituary, mistakenly placing the 1897 Ladies’ International two years later.

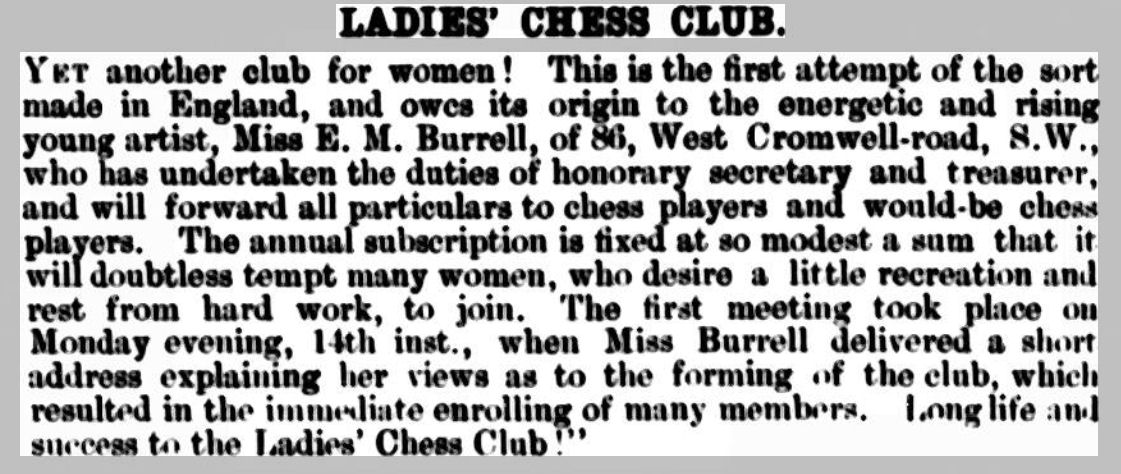

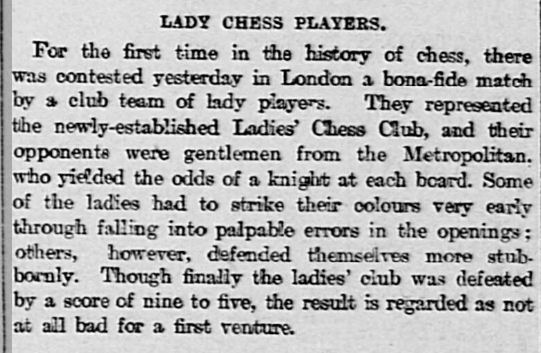

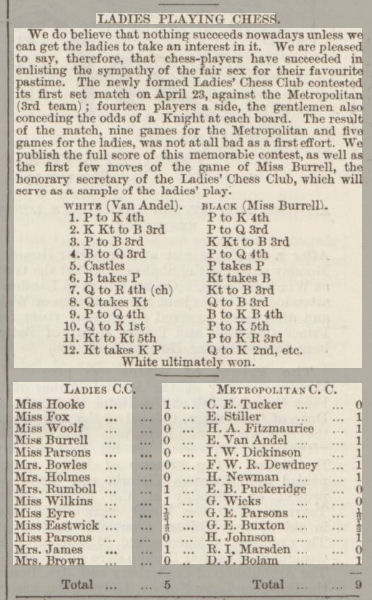

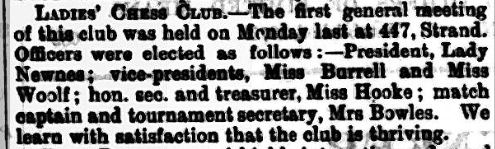

She really deserved better. Alice Elizabeth Hooke played an important part in women’s chess in England for more than forty years, both as a player and as a backroom administrator, from her pioneering work with the Ladies’ Chess Club through to playing club chess into her late 70s. Although she wasn’t all that much more than an average club player herself, she was still good enough to share first place in two British Ladies’ Championships in her late 60s. Reaching your peak at that age is also something to be proud of, I think. As she helped keep Barnes Village club going during the Second World War, you might think that some of her legacy is still present in today’s Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club.

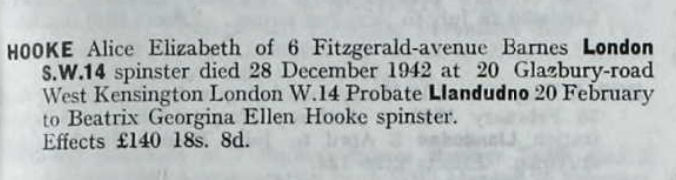

Her probate record indicates that since 1939 she’d moved from Chiswick to Barnes, perhaps to be nearer her brother and niece as well as her chess club. I presume 20 Glazbury Road was, at the time, some sort of nursing home or private hospital.

She didn’t leave very much money: she may well have gifted much of it to her relatives to avoid death duties.

The name of Miss Hooke continued to be prominent in Barnes Village chess through George’s daughter Beatrix.

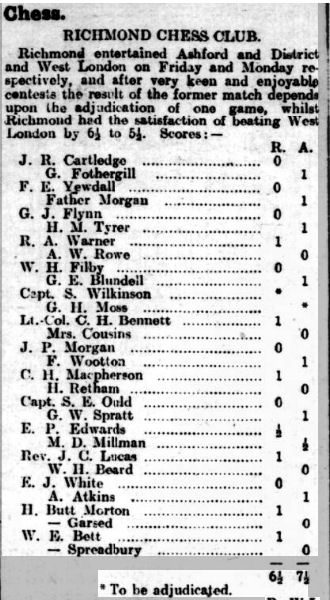

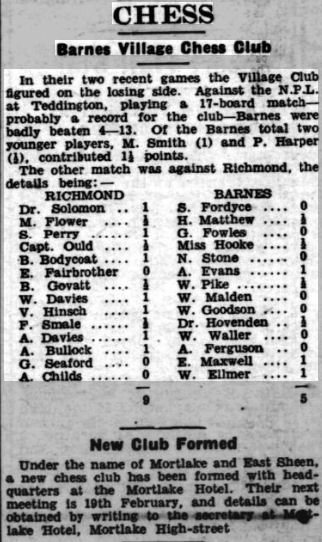

Here she is, in 1948, playing as high as Board 4 in a match against Richmond, who had reconvened after closing during the war. Her opponent, Captain Samuel Ould, had been a Richmond stalwart between the wars, but most of the other Richmond players were relatively new members.

And this is where I come in. I knew George Seaford at what had by that point become Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club, in the 1960s, and Ted Fairbrother into the 1970s, though neither very well. Dr JD Solomon (a strong player) and Stan Perry left Richmond but rejoined for a time in the 1970s, the latter serving a term as Hon Treasurer. There were one or two other Richmond members at the time who would still be involved 20 years later. There was also one player in the team whom I never met, but who had an influence on my early chess career. I’ll write about him another time. The golden thread again.

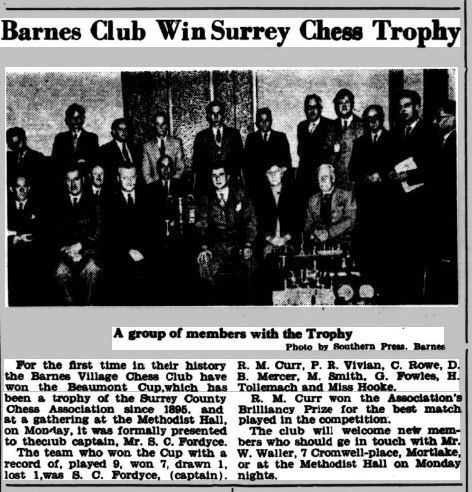

Here Beatrix is again, celebrating Barnes Village winning the Beaumont Cup (Surrey Division 2) for the first time. This was their first, and, as it turned out, their only trophy, as they would eventually be subsumed into Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club. Also in the photograph is young Peter Roger Vivian (1927-1987): I played him at Paignton, also in 1974. Another strand of the thread.

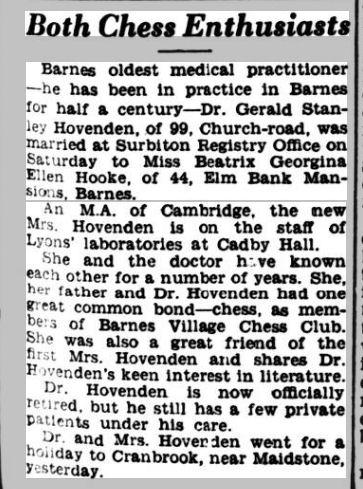

Two of the Barnes Village members had something else to celebrate in 1950: here are Beatrix and her widower clubmate Dr Gerald Hovenden demonstrating how chess can bring people together. At the time of their marriage Beatrix was 57 and Gerald 81.

This tells us she was living in Elm Bank Mansions, right by Barnes Bridge, and working at Cadby Hall near Olympia, just as in the 1939 Register. Perhaps she walked along the riverbank and over Hammersmith Bridge to work, a journey almost identical to that made by her music teacher at St Paul’s Girls School more than 30 years earlier.

This was Gustav Holst, who, at the time, lived in The Terrace, Barnes, just a few yards upstream from Elm Bank Mansions. Always a keen walker, Holst was in the habit of making that journey on foot. Coincidence, or something more?

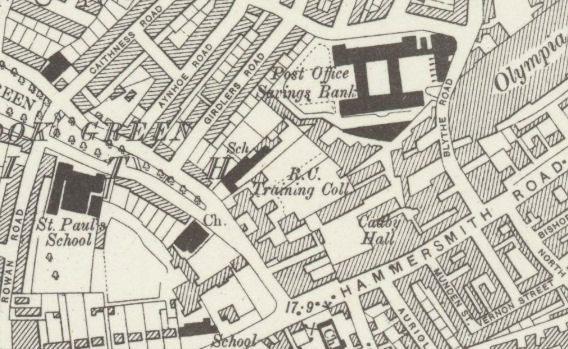

In this map you can see the Post Office Savings Bank in Blythe Road, just opposite Olympia, where Alice spent her career. Cadby Hall, just round the corner, was where Beatrix worked, as a statistician according to the 1939 Register. (As a footnote, in 1926 she co-authored a scientific paper on British skulls in prehistoric times.) Just a few yards again took you to St Paul’s Girls School, marked as St Paul School here, where Gustav Holst taught music to Beatrix and her sisters, while their brother Cyril attended St Paul’s Boys School, just off the map opposite the smaller school on Hammersmith Road. I visited there a couple of times myself in the 1960s for school bridge matches: it was rebuilt in Barnes, the other side of Hammersmith Bridge, a few years later. It’s extraordinary how much of the Hooke family’s lives played out within such a small area of London.

If you continue west along Hammersmith Road, you’ll soon reach Hammersmith Broadway, where Alice was knocked down by a cyclist, and the Underground stations. Continue into King Street and you’ll pass a turning on your right taking you to the London Mind Sports Centre, also the home of Hammersmith Chess Club, and then arrive at Latymer Upper School, a place I used to know very well.

Did Gerald and Beatrix continue playing chess after their marriage? Sadly, the online Richmond Herald records only go up to 1950, so I’d have to get out of my chair to find out. Gerald lived on until 1957, while Beatrix retired to Sussex, where she died in 1974.

That concludes the story of the chess playing Hooke family: George, his sister Alice and his daughter Beatrix. George and Alice were prominent players in earlier decades, but through their work and play at Barnes Village Chess Club for a quarter of a century they had a huge influence on chess in the Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It’s the likes of them, organisers behind the scenes as well as players, who make the chess world go round. Raise a glass to them next time you visit us at the Adelaide.

Supplementary games:

Sources and acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

chessgames.com: Alice’s page here.

Britbase (John Saunders): British Championship links here.

EdoChess (Rod Edwards): Alice’s page here.

chess.com

Streatham & Brixton Chess Club Blog (no longer active)

Google Maps

National Library of Scotland Maps

Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society website

Other sources referenced in the text.