You’ve already read about Charles Dealtry Locock’s career as a chess player and problemist. In the final part of this trilogy you’ll learn more about his life, and about what might be seen as his most lasting and significant contribution to chess.

You’ll recall that he married his first cousin, Ida Gertrude Locock, and that they had two daughters. Both were named after characters in Wagner operas who met unfortunate ends: was Wagner his favourite composer?

Elsa, born in 1891, received her name from a character in Lohengrin, who, to cut a long story short, died of grief after her brother was turned into a swan. She worked for a time as a shorthand typist, did voluntary social work for the Red Cross during the Second World War, and died unmarried in 1985.

Her sister, born in 1894, was named Brynhild, a version of Brünnhilde from the Ring Cycle, a Valkyrie who, to cut a very long story short, rode her horse into a funeral pyre after the death of her lover Siegfried. (If you’d like to find out more, Anna Russell is considerably shorter and much more amusing than Wagner.) In fact her name was registered twice, the second time as Hilda Vivien, which she seemed to prefer. She worked as a children’s nurse, and died, again unmarried, in 1950.

Although Locock gave up competitive over the board chess in 1899, he played on Board 2 for the South of England in a correspondence match against the North the following year. He was matched against the mathematician George Adolphus Schott, winning a brilliant game. As always, click on any move for a pop-up window.

In the 1901 census the family were living in Camberley, on the Surrey-Hampshire border, along with four servants: governess, parlourmaid, cook and housemaid.

Charles’s occupation was described as ‘living on own means & literature”. His particular literary interests were the poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Swedish poetry and drama. It appears that he was also still writing a regular chess column in the science magazine Knowledge at this point (some of them are available online).

The same year he had his first book published: neither literary nor chess related, but about the game of billiards. Entitled Side and Screw, you can read it here.

Chess and billiards weren’t Locock’s only games. He was also very much involved in the game of croquet, editing the Croquet Association Gazette between 1904 and 1915, and being employed as the Croquet Association handicapper from 1907 to 1929.

More books followed: Modern Croquet Tactics in 1907, Olympian Echoes, a book of poems and essays, in 1908 (here), and, in 1911, an edition of Shelley’s poetry (Volume 2 here).

In October 1910 he made a rare appearance at the chessboard, taking part in one of a series of consultation games between the veterans Blackburne and Gunsberg. His team was unsuccessful, but the game was exciting.

By the 1911 census the family were in the Hertfordshire market town of Berkhamsted, now employing only two servants, a Swiss cook and a parlourmaid. Charles’s occupation was given as Editor and Handicapper.

In 1912 he celebrated his 50th birthday by writing his first chess book, which, unfortunately, doesn’t appear to be available online.

By 1915, Charles Dealtry Locock, returned to playing chess, having joined the Imperial Chess Club, here giving a simultaneous display.

Here’s his loss against solicitor George Bodman, formerly of Bexhill, whom he may well have known from his time in Sussex chess.

It’s possible his marriage had broken up by this time, and he was living in London. Either way, the social atmosphere of the Imperial (about which there’s much to be researched and written) would have been ideal for Locock, who loved chess while not enjoying the pressures of competition.

Locock continued at the Imperial for the rest of the decade, and, in 1920, returned to correspondence chess, playing on top board for Kent against an Italian magazine, and scoring the full point when his opponent went wrong in a bishop ending.

In the 1921 census, Charles Dealtry Locock, claiming to be still married, was visiting a widow named Rose Edith Heath in 4 Ferry Road, Barnes. (I got off the bus about 100 metres from there the other day: perhaps I should have walked in the other direction to say hello.) I don’t know whether he was just visiting a friend, or whether there was anything else to their relationship. Ida and Elsa, working for the Red Cross as a shorthand typist, were living in Redcliffe Square, just south of Earl’s Court. Brynhild was in Scarborough, a trained nurse but working as a servant for a young doctor, perhaps helping to care for his infant son. I’d like to think she bought her groceries from Edward Wallis, whose shop was only a short walk away.

By this time, Locock was very much engaged in translating Swedish poetry and plays, particularly those of Strindberg, into English (for which he was awarded a silver medal in 1928), and resigned from his post at the Imperial Chess Club in 1923. He was still actively involved in the world of chess composition, though, publishing another collection of problems and puzzles in 1926.

You might think that, approaching his seventies, it was time to wind down his chess career, but in fact he had a few more moves to make.

In 1930 he published a booklet entitled 100 Chess Maxims (for Beginners and Moderate Players). Perhaps I’ll review this further another time. For the moment I’ll just say that, while it contains much excellent advice, some of the maxims are decidedly odd.

No. 4, for instance (translated into algebraic by Carsten Hansen) advises you not to play your c1-bishop to f4. Devotees of the London System won’t be happy.

Then there’s:

37. The object of the game is to mate, and as quickly as possible. Captures are only made to deprive the king of his defenses.

Perhaps I’m wrong, but I always thought the object of the game was to mate as certainly as possible. If you look back to some of his games in the first article of my Locock trilogy, you’ll see some examples of him playing in exactly this way 40 years or so earlier.

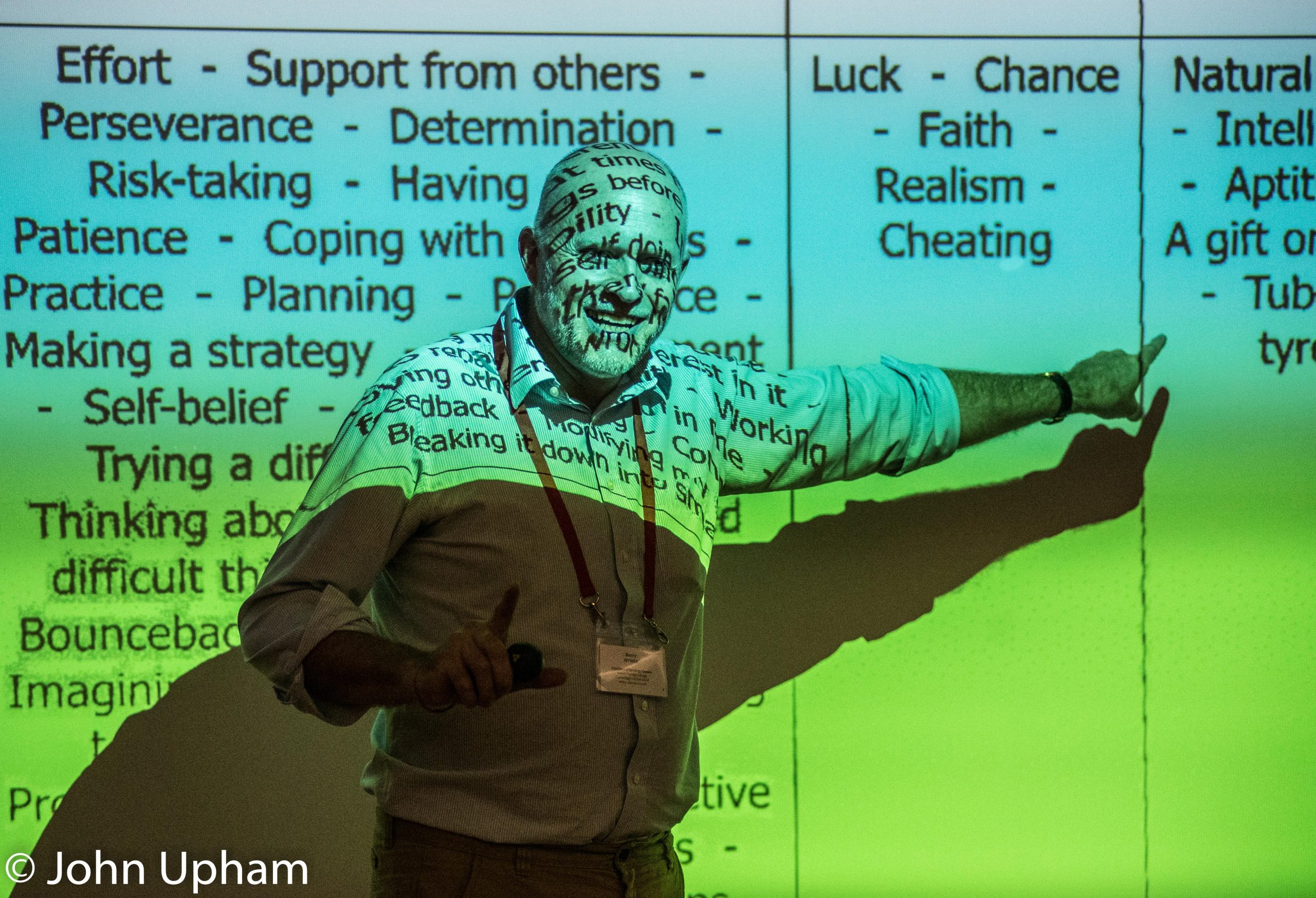

This book might, in part, have been occasioned by Locock’s new career – as a chess teacher in schools, specifically girls’ schools, and specifically the Oratory Central Girls School in Chelsea. He even wrote an article about Chess for Girls for the first issue of the Social Chess Quarterly.

This seems to have been a rival tournament to the British Girls Championship, with which Locock was also involved, which had taken place a few months previously, with the same winner. See BritBase (here) for further information on this event.

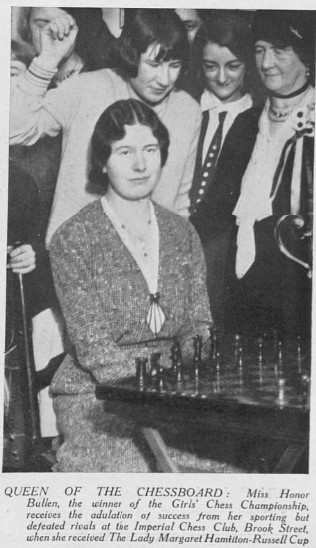

Here’s Honor having just won the earlier tournament.

The school prizegiving that year even included a chess play.

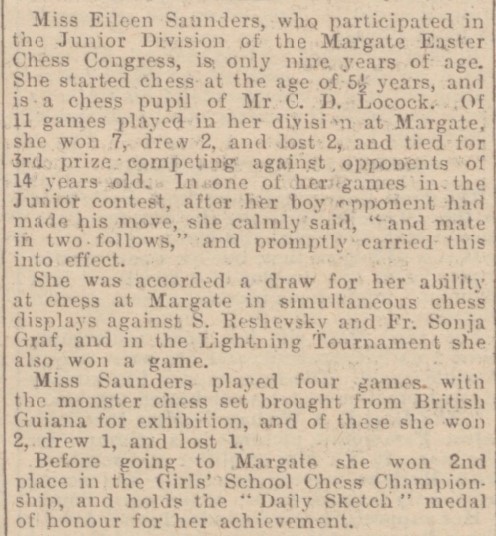

By 1935 one of his very young private pupils was doing rather well.

She was Elaine, not Eileen, and her family were living on the prestigious St Margaret’s Estate, on the borders of Twickenham and Isleworth.

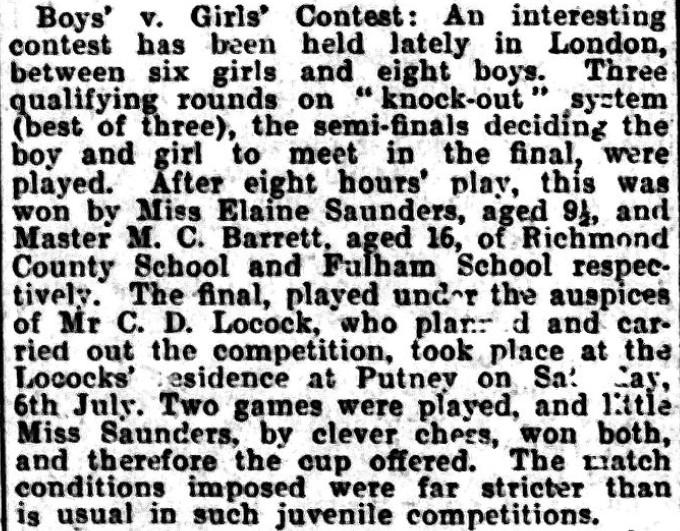

That July she was successful again in a rather unusual event organised by her chess teacher.

Almost half a century later, Elaine wrote (British Chess Pergamon Press 1983):

My father, assisted by a 2d. (= almost 1p) book of rules from Smiths, taught me the moves at somewhere round the age of five. We were rescued by the problemist CD Locock who noticed me playing in a girls’ tournament two years later. It was he who brought me up on a diet of the Scotch, the Evans and any gambit that was going. We analysed them in some depth – for those days – and my severe task-master made me copy out long columns of dubious lines. He also made me his guinea-pig for his Imagination in Chess and it is small wonder that I still find it hard to resist a sacrifice, and much of my undoing comes from premature sorties such as f4 and Qh5.

In retrospect he must have been a brilliant teacher. Starting in 1936 a succession of girls’ titles came my way including the FIDE under-21, and in 1939 the British Ladies at the age of 13. It is hard to assess how strong or weak one was at the time because there has been such a marked improvement in the standard of play among women over recent years. At all events, those pre-war years were happy ones, especially away from chess which took second place to horses and more physical pastimes.

(See here for more on Elaine.)

Yes, we have another book, Imagination in Chess, published in 1937.

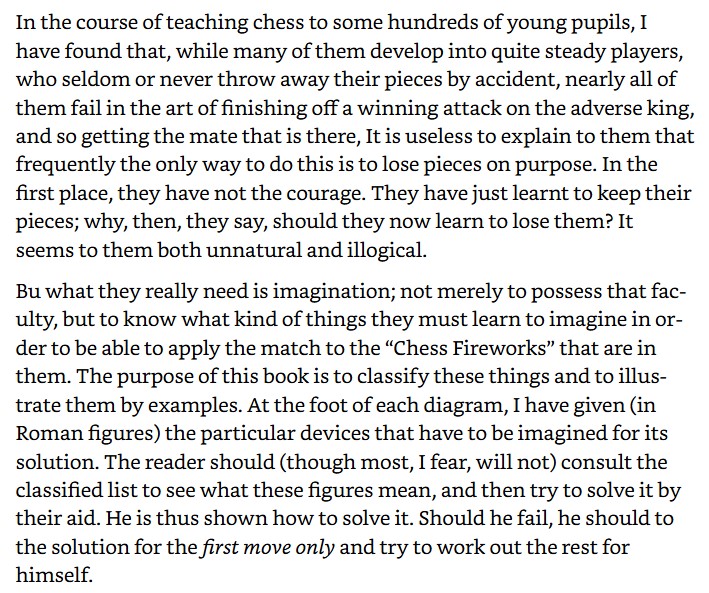

From the author’s introduction:

Based on my own chess teaching experience I have partial sympathy with Locock’s views. I noticed at Richmond Junior Club that children learnt the Two Rooks Checkmate early on, and, if they were winning, would head for that mate, spurning quicker mates in the process. On the other hand, most checkmates don’t require sacrifices, apart from a few stock patterns which need to be remembered, just accurate calculation. While we all like to play brilliant combinations, my view is that, at club level, more games are lost by unsound sacrifices than won by sound sacrifices. Over-emphasising sacrifices to young and inexperienced players can be dangerous.

We have 60 positions, in each of which (with one exception) you can play a problem-like sacrifice to force mate. A halfway house, if you will, between problems and game positions.

A couple of examples:

This is a mate in 3: you’ll want to sacrifice your knight, and then your queen.

Here, you have to mate in 4 moves, being careful to play your sacrifices in the right order: knight, then queen, then the other knight.

If you’d like to see more you’ll be delighted to know that this book has very recently been updated, edited and published by Carsten Hansen, with 100 Chess Maxims added as a bonus. You can buy it here.

Locock also played training games with Elaine, one of which survives.

By the time of the 1939 Register, and with war imminent, the Saunders family had taken the precaution of moving out of London, and were staying in the George & Dragon Hotel in Princes Risborough – and Charles Dealtry Locock (Author, retired) was staying with them. It’s not clear how long they stayed there, and whether or not Locock was only visiting.

When he was writing about synthetic games in 1944, one of his correspondents and collaborators was a young RAF pilot named David Brine Pritchard. I’d like to think they met and perhaps played each other, if only because it would give me a Locock number of 2 (I played David, but not Elaine). I’d also like to think he introduced David to Elaine, as they married in 1952. Their daughter, Wanda, was also a strong chess player.

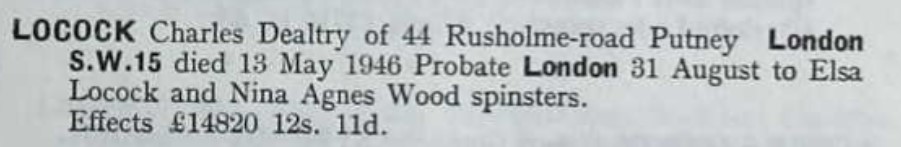

Charles Dealtry Locock died in Putney on 13 May 1946. Here’s his probate record.

I haven’t been able to identify Nina Agnes Wood for certain: the only likely candidate is a journalist named Agnes Nina Wood (1871-1950). I wouldn’t want to speculate.

His wife lived on until the age of 94, dying in 1962 at the same address and leaving £63975 11s: were they reconciled at the end of their lives?

There, in three parts, you have the long and eventful chess career of Charles Dealtry Locock. In the first part we looked at his competitive chess career in the 1880s and 1890s, winning the British Amateur Championship and representing his country. The second part considered his career of more than sixty years as a creative and innovative problemist. But perhaps it’s for his final act, as a pioneer in promoting chess in schools, and, particularly chess for girls, that he should be most remembered. Elaine (Saunders) Pritchard’s memoir confirms that he was a brilliant teacher. More than that, he also pioneered the idea of solving composed positions to teach creativity and imagination. Many chess teachers today encourage their students to solve studies and problems for this reason, but Locock got there first. He should always be an inspiration to all of us involved in junior chess.

Come back soon for the story of another chess prodigy.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

Many thanks to Carsten Hansen for sending me a copy of his new edition of Locock’s Imagination in Chess + 100 Chess Maxims.

Many thanks also to Brian Denman for sending me his file of Locock’s games.

Other sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

Internet Archive

ChessBase 17/Stockfish 16.1