As the British Championships are taking place in Leicester as I write this, it seems appropriate to stay in my father’s home city a while longer and meet one of its finest ever players. Unless you’re in the habit of perusing old newspapers and magazines from a hundred years or so ago, you probably haven’t heard of him. Yet, for about 20 years he was almost invincible in local competitions and more than held his own on top board in county matches when facing some of the country’s strongest players.

Because he chose not to take part in events such as the British Championships or Hastings he never became a household name. Had he done so, he would certainly have performed well at Major Open level, and perhaps gained the experience to reach championship standard.

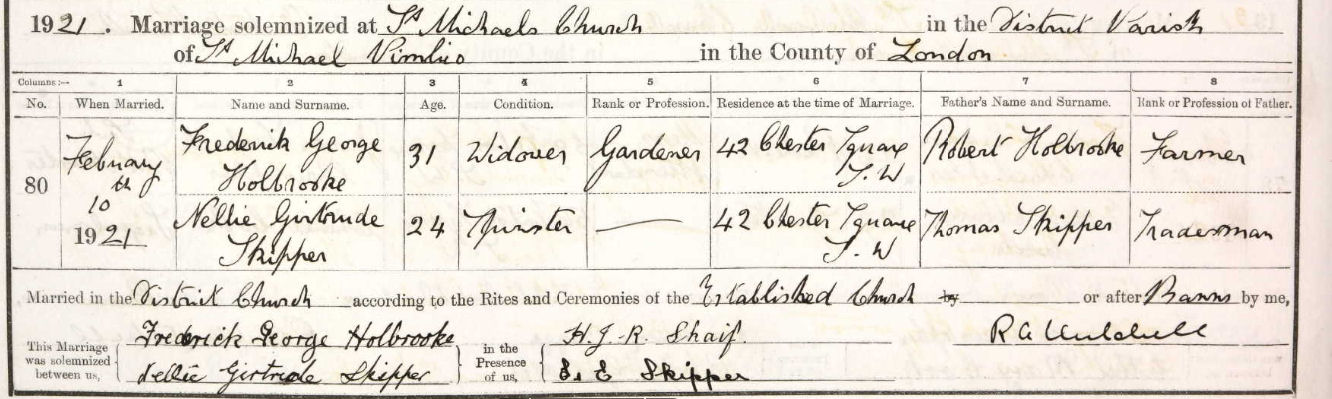

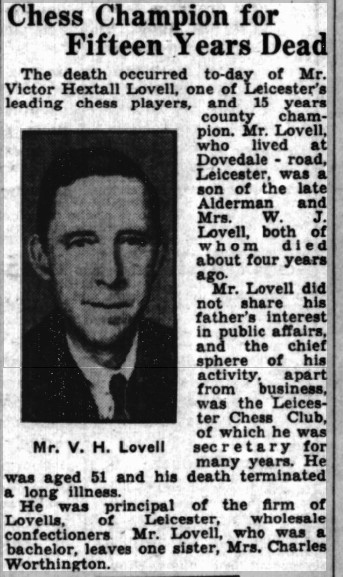

His name was Victor Hextall Lovell, and his birth was registered in the first quarter of 1889. He was probably born on 31 January that year, although there are some inconsistencies in public records. His father, Walter, ran a wholesale confectionery business and was also involved in civic affairs, becoming a local councillor representing the Conservative Party, an Alderman, and, in 1918, Mayor of Leicester.

Victor was educated at Wyggeston Grammar School for Boys, following in the footsteps of Henry Ernest Atkins. A few decades later, Richard and David Attenborough would also be educated there. It seems that, on leaving school, he joined his father’s business and, at the same time, started playing chess in the county league.

The earliest game I have for him is an odds game against Atkins, who was no doubt something of a mentor to young Victor. The master was successful on this occasion, despite giving his pupil the odds of a rook. To play through this or any other game in this article, click on any move for a pop-up window.

It soon became clear that here was a young man of great promise and, by 1910, he was already playing on Board 7 for the county team, winning, in this game, against piano dealer Frederick William Forrest, who miscalculated badly on move 17. (Did he have any connection with the Forrest Cup, since about 1934 the Midland Counties Individual Championship?)

In 1914 Victor Lovell won the county championship for the first time. How appropriate that Victor should be victorious while Miss Champ became Ladies’ Champion. He was also appointed to the role of Hon Secretary, a post he would hold for a quarter of a century.

But then war broke out, although club and county chess continued into the Spring of 1915, when Victor retained his title. Lovell did his bit for the war, serving as a corporal in the 298th Siege Battery of the Royal Garrison Artillery, but was still able to attend the county’s 1916 AGM where he was re-elected as the Hon. Secretary. He saw active service in Ypres in 1917, but he was also ‘attached for a while to the staff of some great man with whom he played innumerable Allgaier Gambits‘ (Gould).

It was not until January 1920 that county matches resumed, with Lovell, now clearly Leicestershire’s leading player, on top board. In 1921 he picked up where he left off, winning the first post-WW1 edition of the county championship. The following year he was unexpectedly beaten by Edward Heath Collier, but resumed his winning ways in 1923. Unfortunately there don’t seem to be any scores of his games available for this period, when he was approaching his peak. Local newspapers had got out of the habit of publishing games, and he didn’t compete in external events.

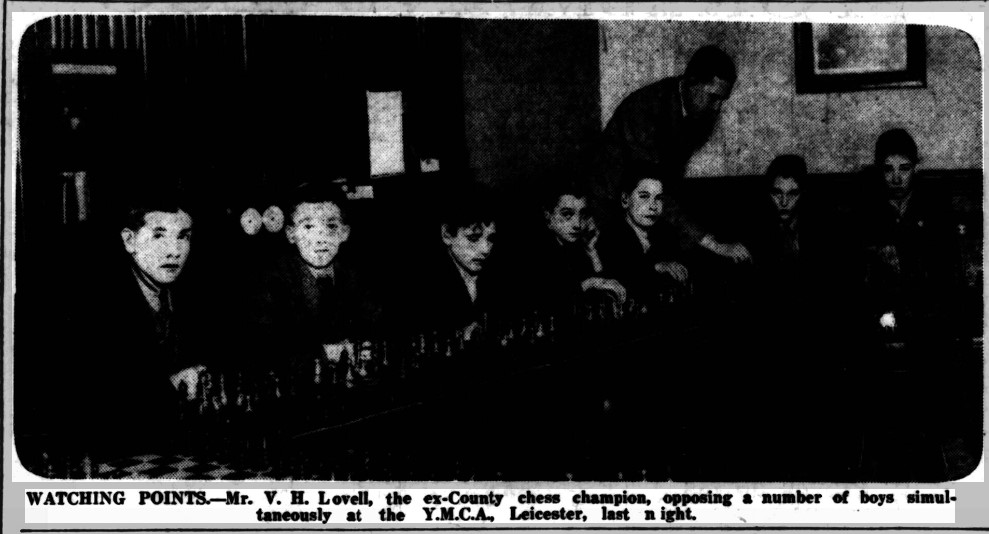

Apart from taking part regularly in club and county matches, Lovell also visited other clubs in the county, and later also schools, to give simultaneous displays.

There was, for many years, some confusion in Leicestershire chess because the main club in the city, calling itself Leicestershire, was responsible for running the county teams and championship as well as competing in the local league. In 1923 they decided not to enter the league, but to concentrate on running internal competitions. VIctor Lovell decided to join the Vaughan College team. Vaughan College, which would later become part of Leicester University, was a Working Men’s College, providing further education for men from what would then have been considered working class backgrounds. The idea of self-improvement for those involved in manual labour was a big thing at the time in many industrial towns and cities, especially so in Leicester. This was my father’s background, but that’s a story for another time and place.

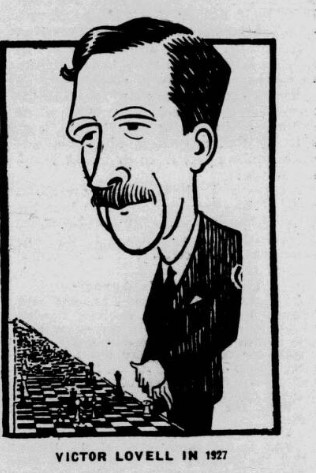

Victor’s chess life continued in very much the same way throughout the 1920s. Here, you can see a caricature from 1927.

In 1930 he won a game in only 14 moves against Warwickshire’s Arthur John Mackenzie, who had been one of the country’s strongest players in his day, but was now rather past his best.

Later the same month he was playing in, rather than giving a simul, against his old mentor Henry Atkins. This time he came out on top.

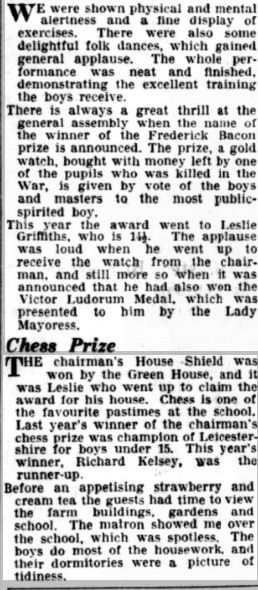

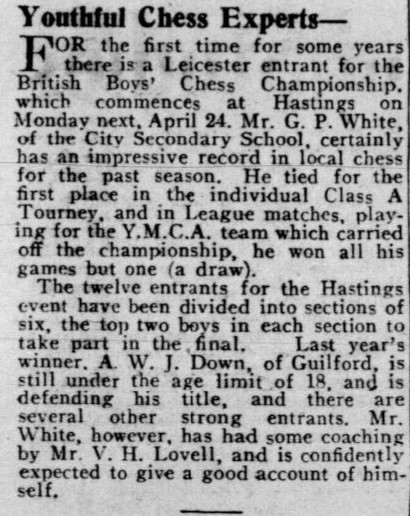

Victor Lovell, apart from being the county’s leading player, was always eager to support youngsters. Aside from vising schools to give simultaneous displays, he also coached the young YMCA player George Percy White before he played in the 1933 British Boys Championship.

George, who had been born on 13 February 1916, did indeed give a good account of himself, finishing in 4th place out of 12 in the Championship section, Alfred Down retaining his title. Most of the other competitors were Grammar School boys, but George was from a working class background: his father was a warehouseman at British United Shoe Machinery, one of Leicester’s largest employers. British United themselves fielded strong teams in the Leicestershire League, but he preferred to play for the YMCA. He was also, I believe, the great-grandnephew of my 3rd cousin 3x removed’s husband. The last chess record I can find for him is selection for a county match in 1938. In 1939 he was working as a dye turner and fitter in shoe machinery, like his father, I suppose, for British United. He married in 1941 and had two children, dying in Leicester in 1985.

There was now a new star on the Leicester chess horizon by the name of Alfred Lenton. Not only was he a fast improving player, he was also a young man with a passion for both reading and writing. In 1933 he started a weekly column in the Leicester Evening Mail in which he often published games from local as well as national and international events. You’ll be able to read a lot more about young Alf in future Minor Pieces.

From here until the column terminated due to WW2 we have a number of Victor Lovell’s games available.

He was ruthless against weaker opponents who failed to calculate accurately, as here against the aforementioned Donald Gould.

In a club match against Hinckley he scored another crushing victory against an opponent who didn’t know the opening well enough (11. d4 was correct). Henry Richmond Fisher was a Medical Officer of Health: one of his brothers was Geoffrey Francis Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1945 to 1961.

At about this time, Lovell, clearly a man ahead of his time, was playing the currently popular London System in some of his games.

In this game he gained revenge for a defeat against the same opponent, also with the London System, the previous year.

The 1934 Leicestershire Championship proved to be a close-run affair, coming down to their individual encounter in the last round. This time it was the older man who prevailed.

Gould takes up the story.

Lightning chess was becoming more popular, and here we have a game from a speed tournament later in 1934. Arthur Ernest Passant had an older brother, Norman Edward Passant, who also played. He really should have reversed his forenames to become EN Passant. The family later moved to Worthing, where, in 1939, Norman was a bank clerk and Arthur a commercial artist.

But by 1935, Victor Lovell’s health started to fail: he had a weak heart. His results became more erratic and his run of twelve consecutive victories in the county championship came to an end at the hands of Lenton.

On a good day, though, he was still able to play powerful chess, in this game using Bird’s Opening (he was also partial to Bird’s Defence to the Ruy Lopez). ‘Rimmington, short and tough, looked like, and was, a rugger forward‘ according to Gould. He was also a cricketer.

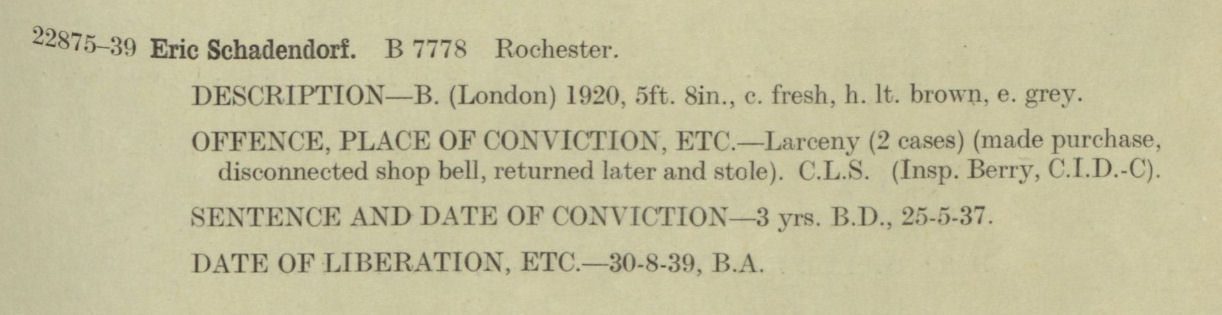

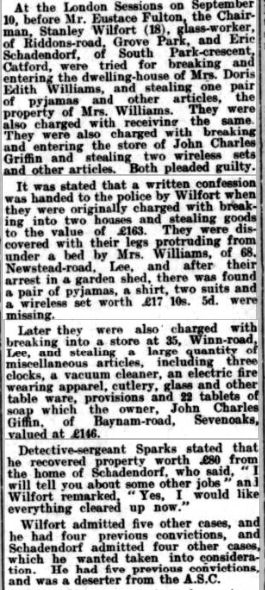

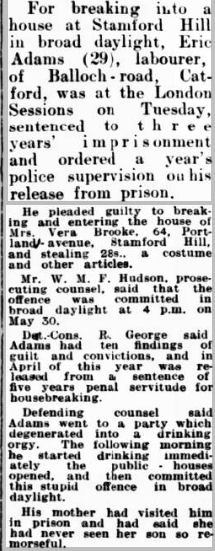

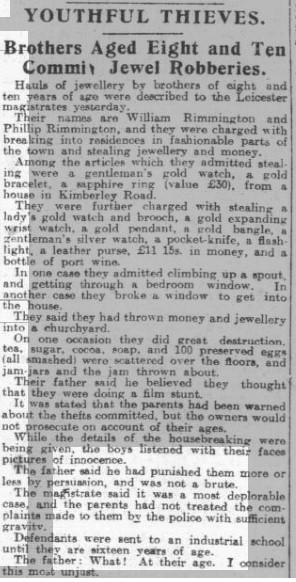

Rimmington’s father was a well-known leather dealer who had had numerous brushes with the law concerning motoring offences. His sons were also no angels. Take a look at this.

Yes, it seems that Phillip, the younger of the two naughty boys, had spent perhaps eight years in Desford Industrial School, as it was then, a decade or so before the boys we met last time. Unlike them, he became a strong player, a regular in the county side up to 1939, and still playing occasionally after WW2. He was also a respected administrator at the Leicester YMCA Chess Club. I wonder if he learnt his chess at Desford. (His brother William was in trouble again in 1934, fined for stealing a Dance Trumpet valued at £19.)

Lenton won the county championship in both 1935 and 1936, but Lovell was still active in many areas of chess. In this photograph he’s taking on a group of boys at the YMCA, where chess seems to have been very popular.

Alfred Lenton didn’t defend his title in 1937, leaving the way clear for Lovell to take his 15th and final title.

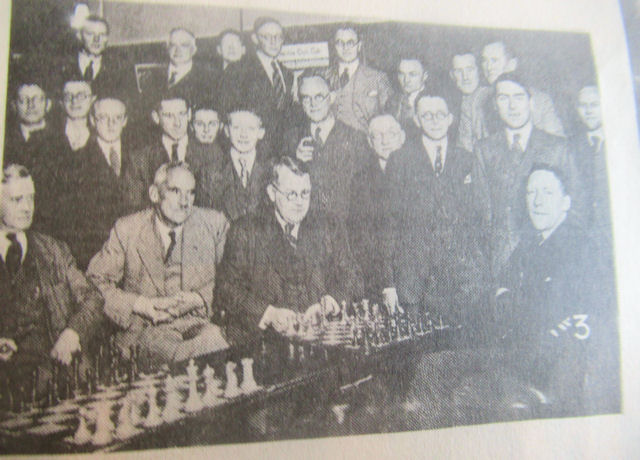

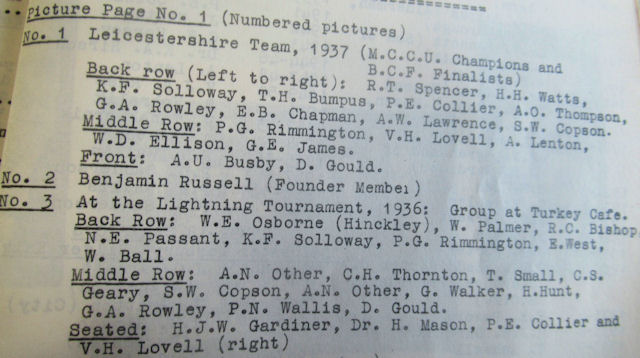

Lovell features in two group photographs from this period. This is the 1937 county team, with Victor Lovell second from the left in the middle row. Infant jewel thief Phillip Rimmington is on his left and Alfred Lenton on his right.

This was taken at a 1936 lightning tournament: Lovell is seated on the far right.

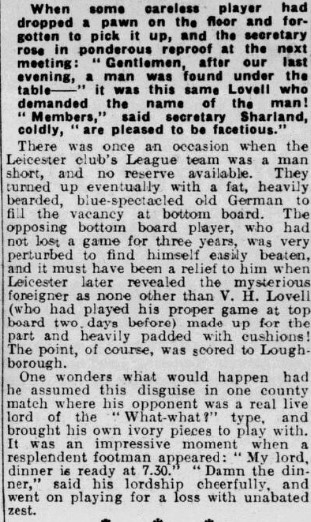

In an article on local chess history in the Leicester Mercury, Donald (styled as Donn) Gould had some amusing anecdotes to relate, one of which referring to a game you saw earlier in this article.

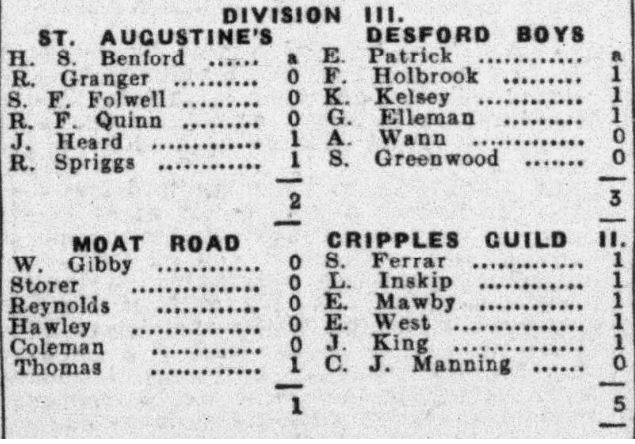

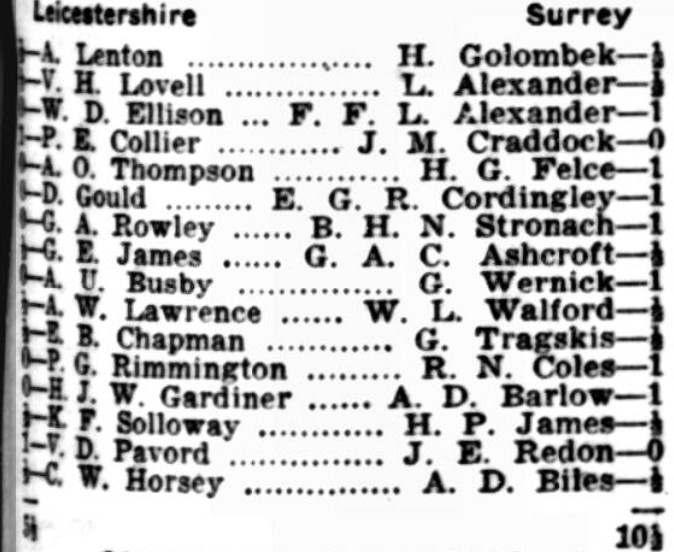

By the time we reach the late 1930s we come across players I knew three decades or more later, as witnessed in this county championship semi-final against Surrey.

Surrey fielded Harry Golombek, a Major Piece who deserves a full biography, on top board. Then there are the two Alexanders, unrelated both to each other and to CHO’D Alexander, both of whom may become subjects of future Minor Pieces. Felce was from a famous family of chess players and administrators. Cordingley became a publisher of chess books. Wernick’s name lives on in a trophy competed for in Surrey. Tregaskis has already featured here. Coles became a respected author and historian – and also beat me in the Surrey Trophy. From a personal perspective, the most significant name is that of Jack Redon, losing here to the unfortunately initialled Vincent Dwelly Pavord. Again, you’ll find out more in a future Minor Piece. I’m not, as far as I know, related to either James, but I do have a distant family connection with one of the other participants. Watch this space.

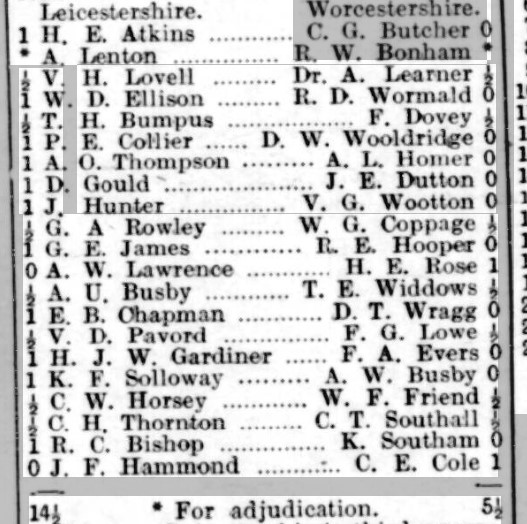

In 1939 Leicestershire scored a big win against Worcestershire in the final of the Midland Counties Championship. The games on boards 1, 2 and 16 were published: Board 2 (perhaps I’ll publish it in a future Minor Piece) was adjudicated a draw, but Stockfish tells me Lenton, a pawn up in a bishops of opposite colour ending, was unfairly done out of half a point.

There are again some interesting names on both sides.

You’ll notice that Henry Atkins was back playing for his home county on top board. Leicestershire’s Board 7, Alfred Oakley Thompson, was a brother of the eccentric John Crittenden Thompson, author of this rare booklet (there should be a copy somewhere in the Chess Palace). You’ll also spot two Minor Pieces, Horsey and Bishop, in their team: they’d later be joined, on a higher board, by AA Castle.

Victor Lovell’s opponent has already featured in an earlier Minor Piece. Worcestershire also fielded the blind player Reginald Walter Bonham on Board 2, and his friend and teaching colleague at Worcester College for the Blind, Robert Douglas Wormald, on Board 4. Of particular interest to me was their Board 20, Keith Southan (not Southam), who later moved to Twickenham, teaching Classics at Tiffin School in Kingston. I knew him well at Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club between the mid 1960s (when he kindly gave me lifts to away matches) and the mid 1970s.

Here’s a game from 1939 between Gould and Lovell, from a match between former pupils of Leicester’s two most prominent Grammar Schools at the time. Gould, like Lenton, was a former pupil of Alderman Newton’s Grammar School, while Lovell, like Atkins, was a former pupil of Wyggeston Boys’ Grammar School. Lenton and Atkins split the point on top board, Charles Hornsby, whom I beat in the Leicestershire League thirty years later, lost on board 7 or the Old Wyggestonians, who, nevertheless, beat the Old Newtonians 4½-3½.

The 1939 Register finds Victor at 42 Dovedale Road Leicester, along with a housekeeper. If he’d travelled a mile and a half or so to the west he’d have encountered my father and his family in Sheridan Street. I’d like to think they passed each other somewhere along the way.

I’ll leave it to Donald Gould to relate Victor Lovell’s rather sad endgame.

The Leicester Evening Mail published this obituary.

And there you have the all too short life of Victor Hextall Lovell, a legendary figure in Leicester chess. At his best, round about 1930, he must have been round about 2250 strength by current standards and they still make a good impression today. He was solid and consistent, with a sharp tactical eye: perhaps it’s to be regretted that he chose not to test himself outside his county. Lenton was of the opinion that he had the talent to become one of the country’s strongest players. Instead, never marrying, he chose to devote his life, outside his family confectionery business, to supporting and promoting chess in his native county.

One final thing. In 1960, his scrapbooks and scoresheets were, along with a lot of other documents of historic interest, in the possession of the Leicestershire Chess Club. I wonder what happened to them. Perhaps they’re now in the ECF Library at De Montfort University. I’ll try to find out, but, if you have any information, do get in touch.

Sources:

Chess in Leicester 1860-1960 Centenary History of the Leicestershire Chess Club (Donald Gould): thanks to Ivor Smith, whose copy I now have, and to Ray Cannon for telling Ivor I would be interested and delivering it to me.

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archive

chessgames.com