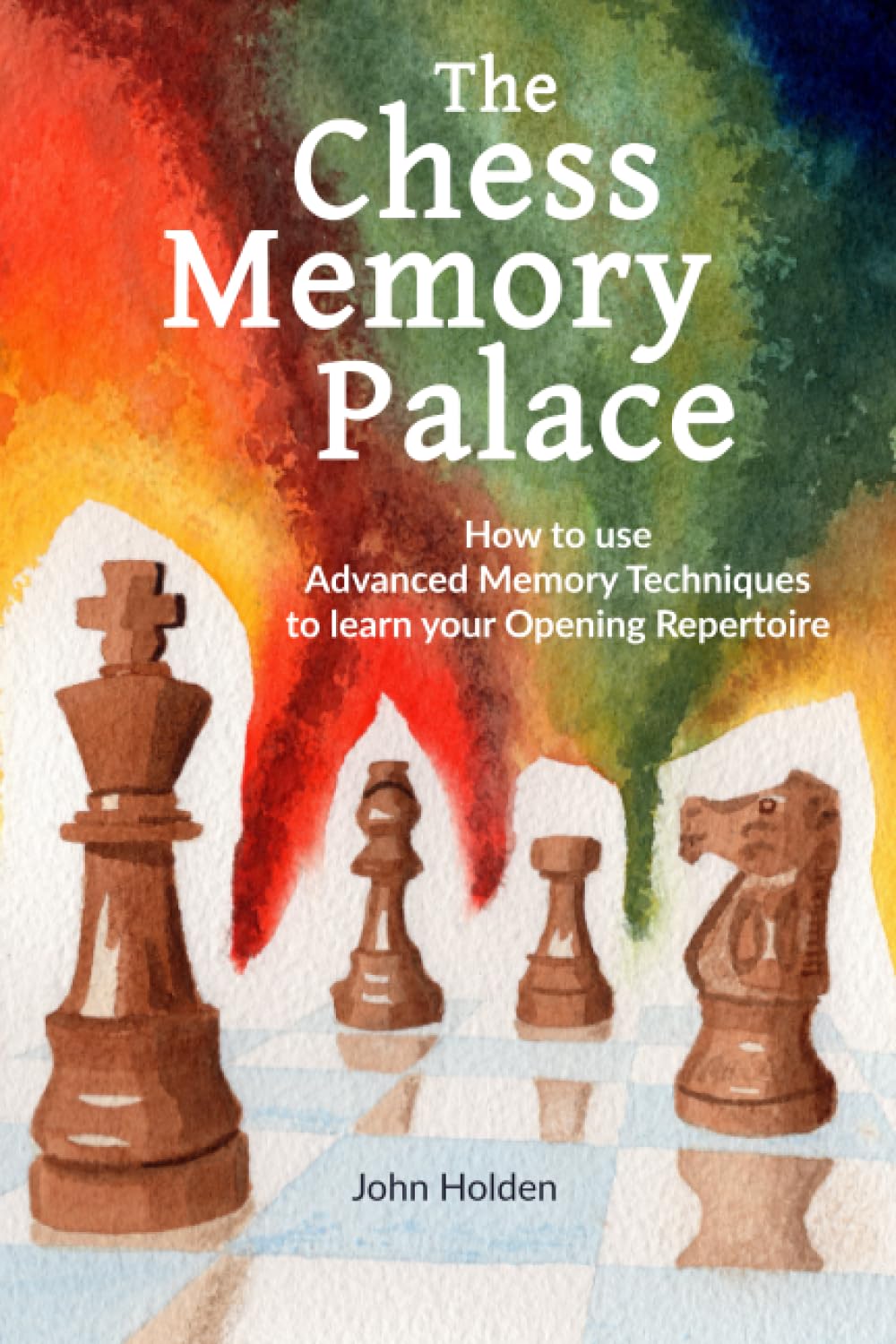

Blurb from the publisher, Amazon:

Chess players spend hours and hours trying to memorize openings, but even Grandmasters forget their preparation.

Meanwhile, memory competitors routinely memorize thousands of facts and random digits, using special techniques that anyone can learn.

This book explains how to use these memory techniques for chess.

- Teaches advanced memory techniques from scratch.

- Contains full worked examples in the Ruy Lopez Exchange and Schliemann Gambit.

- Ideal for tournament players who want to recall their opening repertoire perfectly.

CONTENTS:

Introduction

1. Picture Notation

2. Essential Memory Techniques

3. Memory Palace Architecture

4. Example Palace: The Schliemann Transit Line

5. Example Palace: The Spanish Exchange Airport

6. Bonus: Memorising Endgames

7. Miscellanea

Notes

Appendix: Picture Words for all 64 Squares

About the Author:

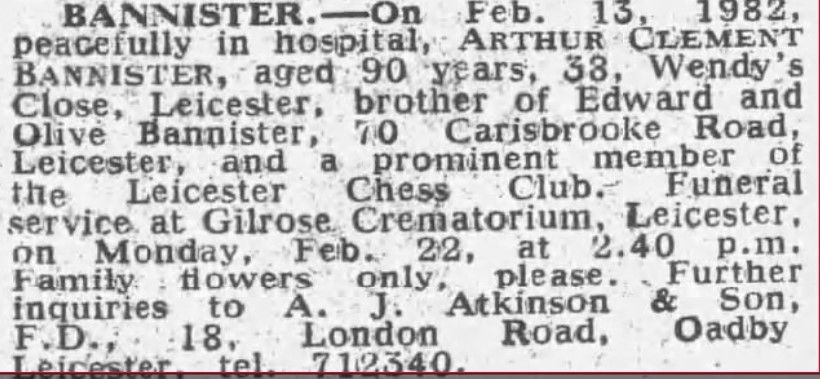

Author of The Chess Memory Palace (2022) and A Curious Letter from Nebuchadnezzar (2021)

I don’t know about you, but I like to know something about the author before I read a book. John Holden seems remarkably coy. It’s clear from the book that he’s a memory expert, but what are his chess credentials?

He tells us in the book that he lives in London, which is a start. His website is johnden.org, and there’s a chess.com user named John Holden whose username is NEDNHOJ (johnden reversed) with a blitz rating round about 900.

There was also a Kent junior on the grading list between 2007 and 2013, when he’d reached 160 (about 1900), who played a few rapidplay tournaments last year, giving him a 1755 rating. Are these the same person? You’d expect someone of that strength to have a higher chess.com rating than 900, especially if he’d put his memory training to good effect.

Is the author, then, either, both or neither?

If you’ve read anything about memory training in the past you’ll be aware of the Memory Palace technique which top competitive memory people use to learn the digits of pi or memorise the order of a shuffled deck of cards.

Here’s the start of the introduction. I have a few questions.

Modern chess requires its players to memorise more and more. “That’s probably the number one thing,” said top grandmaster Hikaru Nakamura, “For becoming a really strong grandmaster today you have to have a really good memory because there’s so much to memorise.”

Yes, if you want to become a really strong grandmaster like Nakamura you need a really good memory. But to what extent is this necessary if you’re a 900 online rapid player like NEDNHOJ or a 1755 rapid player like Kent’s John Holden? From my own experience, playing at that level is probably not about that sort of memory at all, and learning openings in that way might even confuse you.

Most of this effort goes on the opening moves, because you have to survive the opening to demonstrate your middlegame and endgame prowess. Although chess players have a good memory for moves, even elite players can struggle to remember their preparation at the board. And it is a constant source of frustration for all of us to spend so much time rehearsing openings.

There are some (teachers as well as players) who recommend that club level players should concentrate on opening study, while others prefer the 20-40-40 rule: 20% of your time on openings, 40% on middlegames and 40% on endings. Some even think that 20% is too high: you’re better off just playing simple openings leading to playable middlegames. One of the examples here is playing White against the Ruy Lopez Schliemann (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 f5). How often are you going to reach this variation?

Meanwhile, a new sport of competitive memory has sprung up, which reaches new heights every year. The record for most numbers memorised in five minutes stands at over 540. In 15 minutes, 1300. A man from India has recited 70,000 digits of pi.

How is this possible? Is it a special photographic memory? Actually no, it’s the disciplined application of memory techniques – and the techniques are surprisingly simple! They tap into our brains’ natural ability to remember places, images and stories. We can all remember our route to work, and we can all understand a story, even when it’s told to us quite fast. The trick is to convert non-memorable information, like a number, into memorable images.

‘… our brains’ natural ability to remember places, images and stories’. You brain might well work like that but not everyone’s does. You might want to look at conditions such as aphantasia (the inability to form mental pictures) which would make techniques like this difficult, or perhaps impossible.

It’s like everything else: some people are very good at this sort of thing, others fairly average and others again will find it very difficult.

Here’s how it works.

We have eight consonant sounds representing the numbers 1 to 8. Therefore, each square can be associated with a word including the sound representing the file (a-h becomes 1-8) followed by the sound representing the rank (1-8). If more than one piece can move to the same square we deal with this through the number of consonants in the word. If more than one piece can move to the same square you use words with different numbers of syllables to determine which piece you should move.

You might possibly recognise this as a position from one of the main lines of the Schliemann.

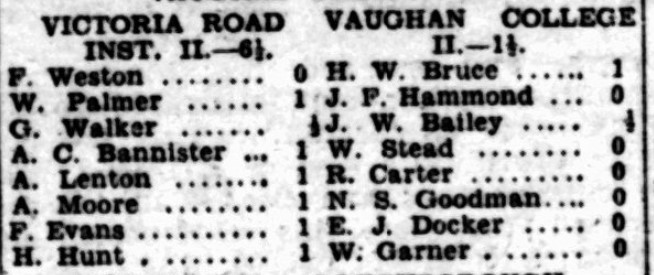

Just out of interest, looking at some lichess stats (filtered on games with an average rating of 1400+:

- e4 e5 (35% in this position)

- Nf3 Nc6 (64% in this position)

- Bb5 f5 (2% in this position)

- Nc3 fxe4 (54% in this position)

- Nxe4 d5 (46% in this position: the other main line, Nf6 is slightly more popular)

- Nxe5 dxe4 (95% in this position)

- Nxg6 Qg5 (62% in this position)

- Qe2 Nf6 (93% in this position)

- f4 Qxf4 (73% in this position)

Realistically, even if you play the Lopez at every opportunity you won’t get the Schliemann very often, and, even then, many of your opponents will choose alternatives at moves 4 or 5. If you’re just a club standard player I’d advise you to play something sensible like 4. d3 instead and get on with the rest of your life.

Anyway, let’s continue. Your opponent has gone down this line and you have to dig into your memory to remember what happens next.

Black’s last move was Qxf4: your word for f4 is ‘shark’ (f/6 is represented by ch/j/tch/sh, d/4 is represented by r, so you choose a monosyllabic word including these two sounds.)

It’s a sharp variation and you want to remember what to do next so you look into your Memory Palace. There you find a shark biting a jester; a match catching fire and burning a lion’s nose, making the lion roar; and a frog chewing gum. The jester gives you lol (laugh out loud, your word for e5), telling you that you now play 10. Ne5+. Well, hang on a minute. Stockfish slightly prefers Nxa7+, and d4 is by far the most popular choice on lichess, but Ne5+ is also fine, so we’ll let it pass. Then we have the match, indicating c6, so we expect our opponent to evade the check by playing 10… c6 – the only good move. Now the lion’s roar tells us to play 11. d4, again clearly best. Then the frog chewing gum gives you 11… Qh4+ 12. g3. It’s still a complicated position so you may need to extend your story a bit.

(If you’re interested in this variation, I’d add that, although 9. f4 is usually played, Stockfish flags 9. Nxa7+ as a significant improvement.)

You see how it works, then, and if you want to play this variation with either colour it’s a sharp line which you need to know well, so, in this case, memory is important.

You should by now have some idea of whether or not this technique will work for you (if you have a strong visual memory it may well do, but if you don’t, it won’t), and whether or not you’re prepared to spend the time to develop your memory in this way and apply it to improving your chess.

The second and third chapters, if you’re still undecided, explain more about memory techniques. The author has helpfully made the first three chapters available for free here.

The next two chapters provide worked examples. Chapter 4 returns to the variation of the Schliemann we looked at earlier, looking at it in more detail, including other variations that Black might choose. John Holden sees this as resembling a train journey: he’s very familiar with the journey on the London Underground from Waterloo to West Ham,

Chapter 5 takes a very different variation of the Lopez: the exchange variation, which is considered from Black’s perspective.

We’re most likely to reach this position, where White usually retreats the knight to either b3 or e2. In either case, Black will trade queens.

This time, Holden’s setting is an airport, where Ne2 is a journey through security to a connecting flight, while Nb3 takes you through immigration to leave the airport.

Again, I have a question. Yes, I can understand you need to memorise the moves in a tactical variation like the Schliemann line discussed earlier, but in this quiet line with an early queen exchange, understanding positional ideas might be more helpful.

Chapter 6 is a bonus chapter explaining how you can use the Memory Palace idea to learn theoretical endings such as KQ v KR. Chapter 7 is a miscellany, answering some of the questions you may have and tying up some loose ends. Holden mentions other learning techniques such as flashcards and spaced repetition, which I’m aware other improvers have used with success.

I notice that this book has been one of the best selling chess books on Amazon since its publication. The book is well written, well produced and well researched, and is being strongly promoted by its author, including sending a review copy to British Chess News. I’m all in favour of supporting authors who are self-publishing on Amazon if their books have something worthwhile to say (and I hope you’ll support my Chess Heroes books as well). John Holden is clearly very knowledgeable on the subject of memory training and, if you’re interested, you’ll want to read this book. However, I remain to be convinced that his chess knowledge is sufficient to make a good case for his methods.

You might have read other chess self-help books in which authors explain the methods they used to improve their rating. If the author had been able to relate how he had improved his rating as a result of using these techniques I might have been impressed, but, as far as I can tell, his rating appears to be modest and perhaps lower than when he was a junior.

Perhaps at some point I’ll write more about the place of memory in chess and how different peoples’ memory works in different ways. I know I’m not alone in thinking very much in words rather than pictures: I have a good memory for words, facts and connections but very little visual imagination and a relatively poor memory for images (which is why I can’t play blindfold chess). For this reason the method outlined here wouldn’t work for me. But, if your brain works in a different way to mine, it might be just the book to help you improve your opening knowledge and endgame techniques. I’d certainly be very interested to hear from anyone who has made a dramatic rating gain by using the Memory Palace method. But until I’ve seen some evidence I’ll remain sceptical.

Richard James, Twickenham 17th October 2023

Book Details :

- Hardcover : 206 pages

- Publisher: Amazon (15 July 2021)

- Language: English

- ISBN-13:979-8370251146

- Product Dimensions: 15.24 x 1.19 x 22.86 cm

Official web site of Amazon Purchase location

Tournament report

Tournament report