Sir Charles Locock (1799-1875) was an interesting chap. Queen Victoria’s obstretician, he also pioneered potassium bromide as a treatment for epilepsy and conducted the autopsy in the notorious Eastbourne Manslaughter Case, establishing that an unfortunate 15-year-old boy had died as a result of corporal punishment.

Locock had five sons, four of whom had distinguished careers. Charles junior became a barrister, Alfred a clergyman, Sidney a diplomat and Herbert an army officer. The middle son, Frederick, though, was the black sheep of the family. He married the illegitimate daughter of a labourer and brought up a son who claimed he was the illegitimate child of Princess Louise. There’s little evidence that this might be true, so we’ll move swiftly on to the Reverend Alfred Henry Locock.

Alfred married Anna Maria Dealtry: their four children were Ella, Charles Dealtry, Henry and Mabel.

Charles Dealtry Locock, born in Brighton on 27 September 1862, was a lifelong chess addict. He started playing chess at his prep school, Cheam, which is now in Hampshire, but really was in Cheam in those days, delivering a back rank mate at the age of 6 or 7, and later winning a tournament there. I would have thought chess tournaments at prep schools were quite unusual in those days. Moving to Winchester at the age of 13, and playing chess on his first evening there, he could find no one to beat him, instead immersing himself in the world of chess problems.

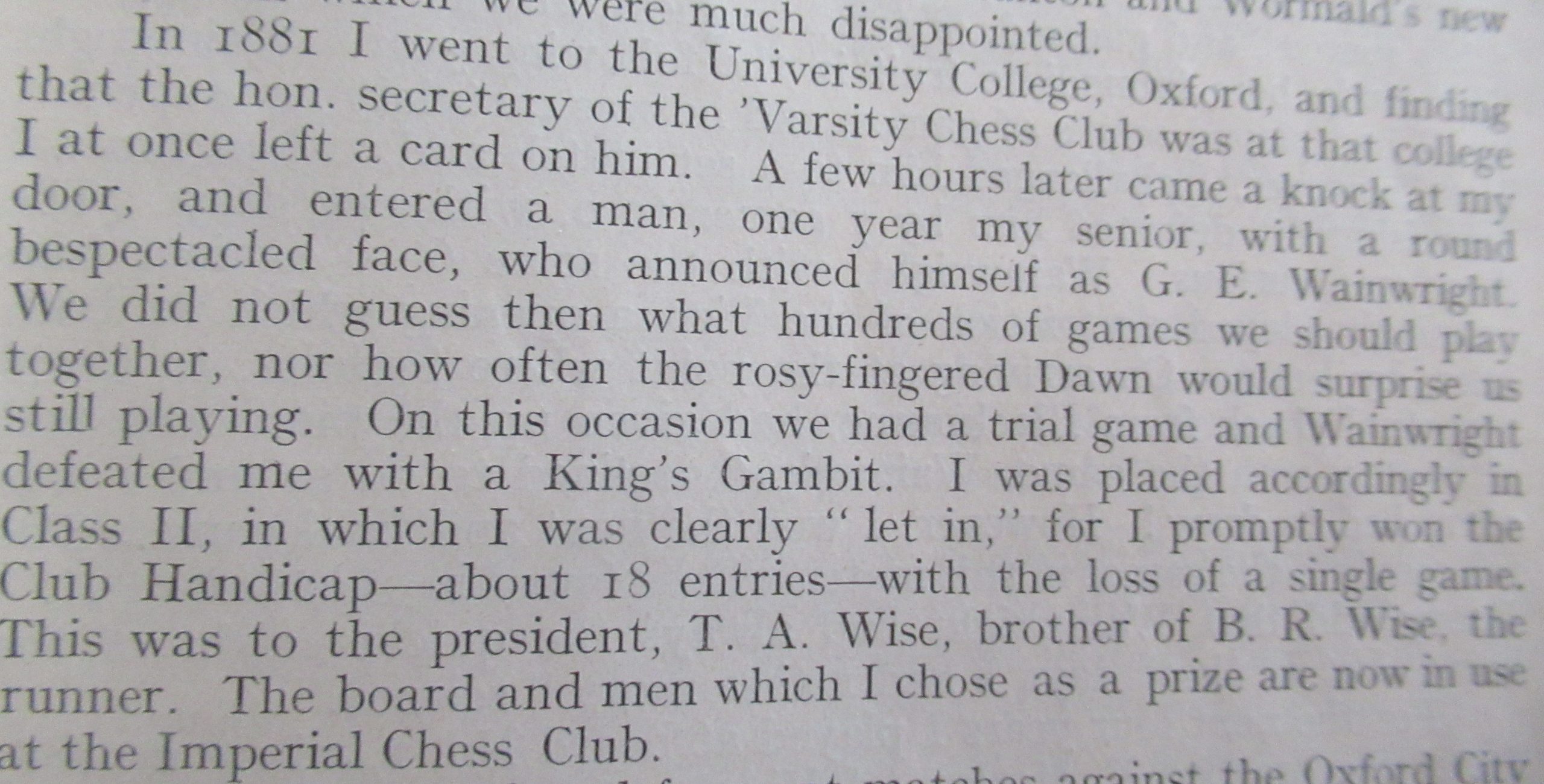

In Autumn 1881 Locock went up to University College Oxford, where he takes up the story.

Wainwright (see here, here and here) was sufficiently impressed to select his adversary for matches against the Oxford city club, Birmingham and the City of London club. At first he was placed on bottom board, but rapidly worked his way up the board order.

In those days the standard of play in the universities wasn’t strong, and their teams would take on the Knight’s Class players of the City of London Club (who would receive knight odds from the top players). Here, he describes a game was one of those matches.

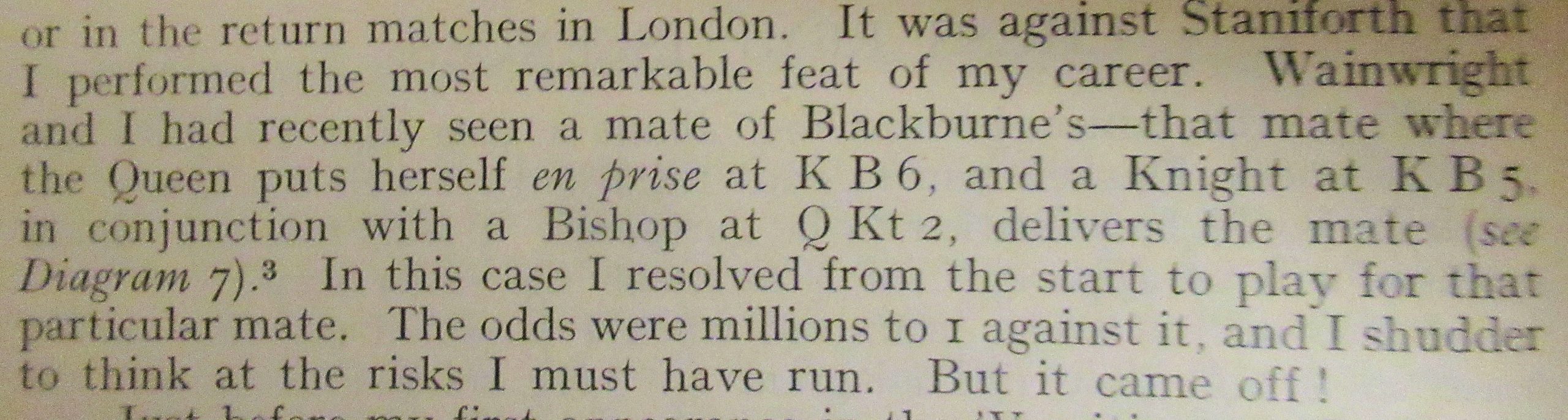

I’m not sure how reliable Locock’s memoir is. We do have a game against Staniforth with a bishop on b2, but otherwise it doesn’t match this description. As with all the games in this article, just click on any move for a pop-up window.

By the 1882 Varsity Match Locock had reached Board 3, where he scored a draw and a win against Edward Lancelot Raymond. He already had quite a reputation as a tactician, the BCM describing him as ‘perhaps the most brilliant and attacking player now at either University’. Unfortunately, the score of his second game, decided ‘by an uncommonly happy series of finishing strokes’, does not appear to have survived.

The 1883 Varsity Match found Locock on top board against Frank Morley. The first game was a solid draw, but the second was more exciting. Zukertort adjudicated the game a draw, but today’s engines give Morley (Black, to play) a winning advantage after h5 (or h6) followed by Ng4.

That summer he played his first tournament, the Second Class section of the Counties Chess Association meeting in Birmingham, scoring 10/14 for second place, a point behind Pollock.

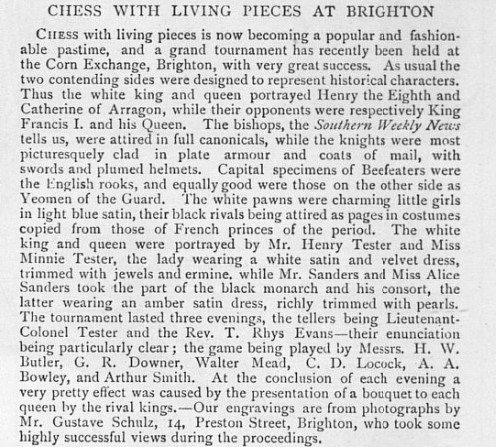

In October that year he took part in a Living Chess exhibition in his home town of Brighton. It all sounded rather splendid.

Playing against auctioneer and estate agent Walter Mead, early exchanges led to Locock being a pawn down. Exchanges in living chess games are always fun, but didn’t really play to his strengths. (The game had actually been played the previous day: they re-created the moves for the exhibition.)

Round about this point we have a mystery. Several correspondence games between Locock and FA Vincent were published, dated 1884. Locock’s memoirs suggest they were actually played much earlier, when he was still at school. They also state that his opponent was Mrs Vincent, while newspaper columns of the time refer to this player as Mr Vincent. We can identify Francis Arthur Frederick Vincent, a retired Indian Civil Servant who had been born in Singapore, living in Cam, Gloucestershire (not far from Slimbridge Wetland Centre) with his wife, born, rather strangely, Sutherland Rebecca Sutherland. It’s not clear which of them was the chess player, or whether they might have collaborated on their games. If you know more than I do, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

In the 1884 Varsity Match Locock again faced Frank Morley on top board. This time they only had time for one game, and, more than compensating for the previous year’s incorrect adjudication, he was awarded a win in a lost position, even though Bird, the adjudicator, spent 15 minutes determining what the result should be.

In summer 1884 Locock was promoted to Division 2 of the First Class tournament in the Counties Chess Association gathering, held that year in Bath, finishing on 4½/10. First place was divided between Fedden, Loman and Pollock.

However, his game against Blake, where, after getting the worst of the opening, he successfully ventured a positional queen sacrifice for two minor pieces, demonstrated exactly why his creativity, imagination and tactical ability were so highly regarded. He must have seen at move 18 that his queen was being trapped.

Here’s a position from a game against Colonel Duncan of the St George’s Club (whom I suspect was this rather interesting fellow) he sacrificed four pawns for nebulous attacking chances against his opponent’s Benoni formation.

He was rewarded when the Colonel overlooked his threat, playing 31… b3?? (there were plenty of good defences available), allowing 32. Qxh6!! Kg8 33. Rxg6 with a winning attack.

In the 1885 Varsity Match Locock was again on top board, this time facing a former prodigy, John Drew Roberts. This game suggested that, although he excelled at attacking play, he was less comfortable in endings.

Here, Locock (Black, to move), would have been slightly better after a move like d4 or a5, but misguidedly played 32… b5?, allowing 33. b4!, fixing some pawns on the same colour square as his bishop.

A few moves later he erred again: Bd7, for example, should hold, but after 35… Rf8? 36. Rxf8+ Kxf8 37. b4! he was saddled with a bad bishop against a good knight. Roberts converted his advantage efficiently.

From these examples, we can see that Locock was a player with very specific strengths and weaknesses.

The 1885 Counties Chess Association meeting was held in Hereford, and, in the Class 1A tournament he shared first place with another old friend of ours, George Archer Hooke.

The game between the two winners was a very exciting affair which Locock really should have won, but positions with queens flying round an open board are never easy to calculate.

Locock’s fifth and last Varsity Match appearance in 1886 was another defeat, when he misdefended against Herman George Gwinner’s kingside attack. That year he finally graduated with honours in Classics.

In the Counties Chess Association meeting in Nottingham he encountered two members of the Marriott family in the Minor Tournament Division 1. John Owen took first place, ahead of Edwin Marriott, with Locock, Thomas Marriott and George MacDonnell sharing third place. Although he lost to both Marriotts he managed to beat Owen, who blundered in what should have been a drawn ending.

Locock then took a job as an assistant master at Worcester Cathedral School, whose headmaster, William Ernest Bolland, was a chess acquaintance of his.

In August 1887, placed in a stronger section, he disappointed in the Counties Chess Association meeting in Stamford. Blake won with 5/6, and Locock’s solitary point left him in last place.

Later in the year (I’m not sure how he managed to get the time off his teaching job) he took part in the Amateur Championship in the 3rd British Chess Association Congress. He won his qualifying group, shared 1st place in the final group, where he encountered his old University friend Wainwright, and won the play-off against Frederick Anger, making him the British Amateur Chess Champion.

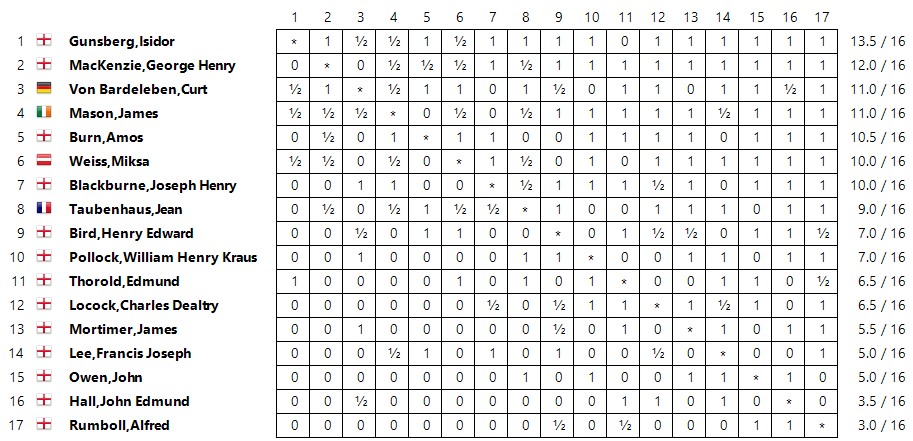

August 1888 gave Locock his first taste of international chess. The British Chess Association held a tournament in Bradford, and Locock was invited to take part. His score was respectable given the strength of the opposition.

It could have been so much better, though. He certainly should have beaten MacKenzie in the first round.

He lost in ridiculous fashion against the tournament winner in a game which he might later have confused with the Staniforth game.

Either Nxg7 or the simple Rxe1 would have given him a very large advantage, but instead he played the absurd Qh6??, simply overlooking that Black could block the discovered check with f6.

His game against Mortimer again demonstrated his prowess in the Ruy Lopez.

On 12 February 1889, at St George’s Hanover Square, Charles Dealtry Locock married his first cousin, Ida Gertrude Locock, a daughter of Charles’s army officer Uncle Herbert. They can’t have had much time for a honeymoon as he was soon in action again over the board.

In a March 1889 match between Oxford Past and Cambridge Past (the first of what would become an annual event) he faced an interesting opponent in economist John Neville Keynes, the father of John Maynard Keynes.

Again he attacked strongly in the opening, but missed the best continuation, allowing his opponent to equalise, and then blundered in what should have been a drawn ending.

They met again in the same fixture two years later, the game resulting in a draw.

At the end of 1889 Locock resigned his position at Worcester Cathedral School, briefly taking a post at Hereford Grammar School before moving to London.

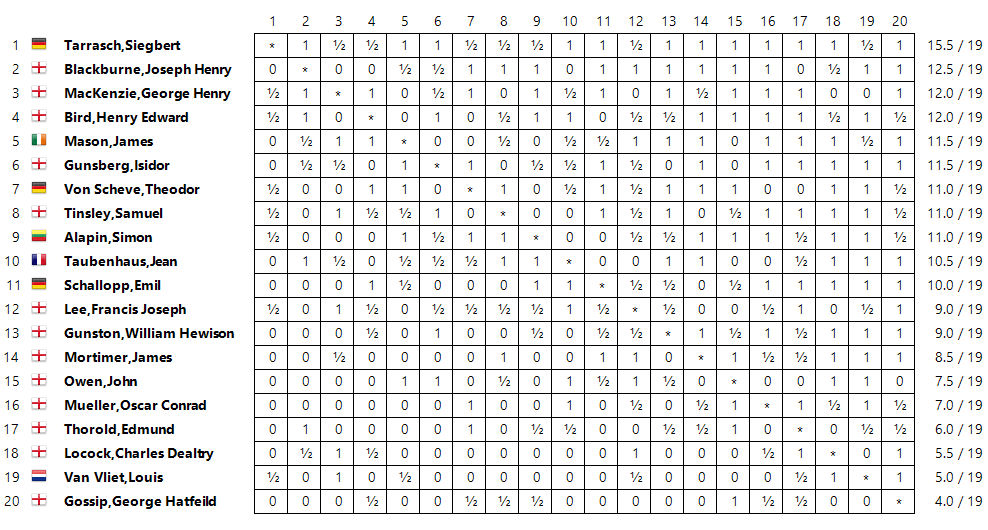

The BCA ran another strong international tournament in 1890, this time in Manchester. This time Locock was less successful, although he did score 50% against the top four.

Unlike two years before, he made no mistake against MacKenzie.

In 1891 Locock’s first daughter was born in Hawkhurst, Kent, although his location was still being given as London at the time. He was also still playing at the British Chess Club, winning this brilliant miniature against a strong opponent in their handicap tournament.

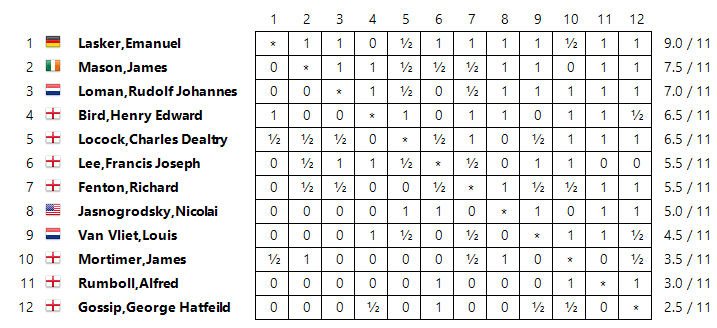

In 1892 the BCA ran another international tournament, this time in London, with the participation of the young Emanuel Lasker. Locock did well to score 6½/11.

Unfortunately, his draw against Lasker doesn’t appear to have been published, but we do have this game.

This would be his last tournament, although he continued playing in matches for several more years.

Soon afterwards Charles Dealtry Locock and his family moved out of London and back to his county of birth, settling in the village of Burwash, not all that far from Hawkhurst. Although it was 15 miles away, he wasn’t deterred from joining the Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club.

It was in Burwash that his second daughter was born in 1894. Meanwhile, he was taking part in county and other matches, and playing consultation games with other leading players, a popular feature of Hastings chess at the time.

Here’s an exciting example in which he had a very strong partner.

One of the opposing team would late meet a tragic end, as described in Edward Winter’s excellent and thorough article here.

The same year a cable match took place between the British and Manhattan Chess Clubs, which was the predecessor of the official Anglo-American Cable Matches starting the following year. Locock was matched against Albert Beauregard Hodges: their game was drawn in 28 moves.

As a gentleman amateur he was just the sort of chap the selectors were looking for, and, although he was no longer an active tournament player he was selected for the Great Britain team for the first four matches. In 1896 he drew a fairly long ending against Edward Hynes, but in 1897 he was well beaten by Jackson Whipps Showalter.

Locock, playing Black, had misplayed the opening, and now Showalter replied to 14… Bxg5 with 15. Rxd7! Kxd7 16. Qg4+ Qe6 17. Qd4+ Kc8 18. Bxg5, having no problem converting his advantage.

This very short consultation game is (or at least was) perhaps his best known game, although it’s not clear whether the game lasted 9 or 18 moves. Unsurprisingly, it involves a queen sacrifice.

This position, from an 1897 match between North London and Hastings & St Leonards, is another demonstration of how Locock’s predilection for sacrifices could end up looking foolish.

He was Black here against Joseph William Hunt.

Locock being Locock, he couldn’t resist the Greek Gift sacrifice here. 11… Bxh2? 12. Kxh2 Ng4+. Here, Hunt played 13. Kg3?, which was unclear, the game eventually resulting in a draw, but 13. Kg1! Qh4 14. Bf4! would have left Black with very little for the piece. These sacrifices usually don’t work if your opponent has a diagonal defence of this nature: there are one or two examples of this in Chess Heroes: Puzzles Book 1. Curiously, the notes in the Pall Mall Gazette (Gunsberg?) claim that 13. Kg1 ‘was obviously impossible owing to Qh4 by Black’. Obviously not, but newspaper annotations, without Stockfish to assist and probably written overnight, were very poor in those days.

In the 1898 Cable Match Locock drew with David Graham Baird, this time missing an early tactical opportunity.

15… Bf3! 16. gxf3 Qh3 was winning, but instead he played 15… g5 and after 16. f3 White was safe, the game eventually resulted in a draw after a long double rook ending.

Locock’s opponent in the 1899 Cable Match was Sidney Paine Johnston.

Here’s the game.

Locock missed a win: 28. Qxe6+ Kh8 29. Rd8!, while Johnston in turn missed 29… Qh6!

There was quite a lot of comment in the press about Locock’s miss. Here’s the Morning Post (Antony Guest):

Morning Post 13 March 1899

Stung by this criticism, he decided it was time to give up competitive over-the-board chess. He kept his word, too. In 1901 it was announced that he’d compete in the Kent Congress, but he changed his mind. This was indeed the end of that part of his chess career.

Many years later he recalled:

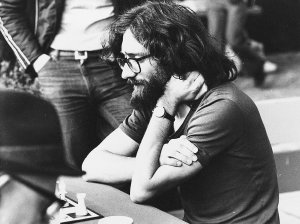

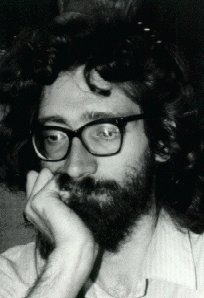

What, then, should we make of Charles Dealtry Locock (pictured above) as a chess player? He was clearly a very creative and imaginative tactician, who, at his best, was of master standard for his day (EdoChess rates him as 2346 in 1892), but his constant quest for brilliancy led him to play the occasional silly move, and he sometimes missed tactical opportunities, particularly if they involved more unusual ideas. He also seemed to find endings rather boring. But perhaps, judging from the quote above, he wasn’t temperamentally suited to competitive chess, finding the pressure of the ticking clock too stressful. I can empathise. Fortunately for him, there were other ways to fuel his chess addiction.

You’ll find out more in my next two Minor Pieces.

Sources and Acknowledgements

Many thanks, first of all, to Brian Denman for kindly sending me his extensive file of Locock games.

Locock’s memoirs, quoted in several places above, and written with a combination of arrogance, false modesty and facetiousness, were published in the January 1933 issue of the British Chess Magazine.

Other sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

BritBase (John Saunders)

Chess Notes (Edward Winter)

ChessBase 17/MegaBase 2023/Stockfish 16.1

chessgames.com (Locock here)

EdoChess (Rod Edwards: Locock here)

Correspondence Chess in Britain and Ireland 1824-1987 and British Chess Literature to 1914, both written by Tim Harding and published by McFarland & Company Inc.