Last time we left London chess professional Francis Joseph Lee as the calendar turned from 1899 into 1900.

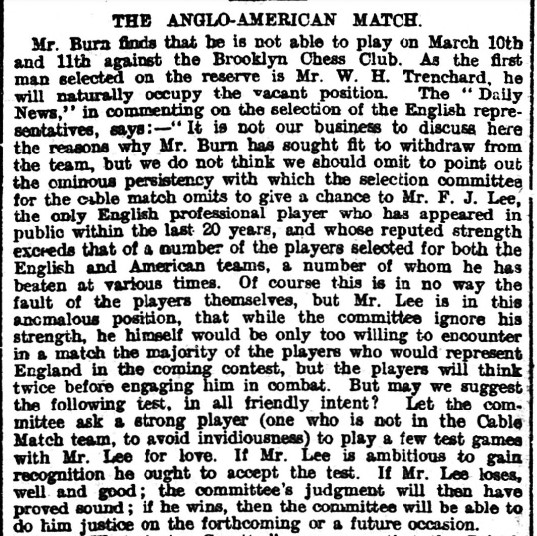

He was finally selected for the Anglo-American Cable Match that year, being assigned to Board 2 where he took the white pieces against one of his London 1899 opponents, Jackson Whipps Showalter. Standing worse much of the way he managed to escape into a somewhat fortunate draw.

This was the critical position, with Black to play his 45th move.

Stockfish tells me Black is winning easily if he goes after the h-pawn, but, in the heat of battle, it’s very tempting to target the dangerous looking a-pawn instead. The game concluded 45… Ra1? 46. Nc4 Rxa4? (Kf6 still offered some winning chances) 47. Nxe5 Kd6 48. Nf3, and the combatants agreed to share the point.

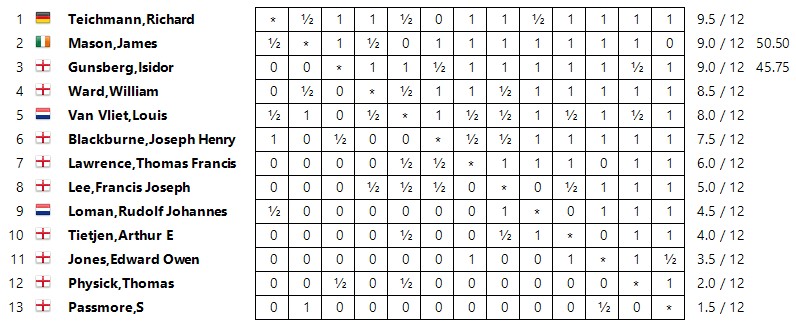

In April Lee took part in an invitation tournament run by the City of London club, where his result was about what he would have expected, although he only managed to beat the three tail-enders.

In this game his knights on the rim were far from dim. (As always, click on any move for a pop-up window.)

A match against Passmore that summer was won by 5 points to 3. In December he finished second to Teichmann in a 5-player tournament at Simpson’s Divan.

In this game he was successful with the London System.

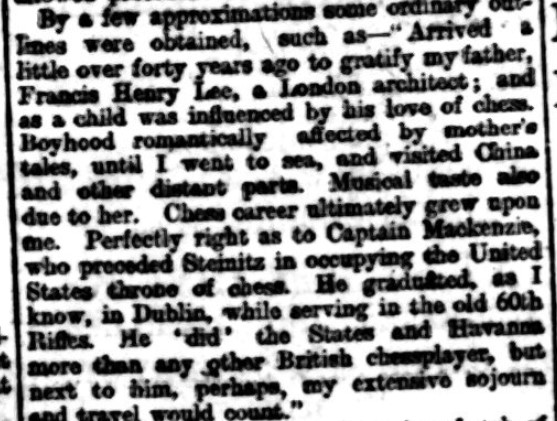

In 1901 Francis Joseph Lee was on tour again, returning to Ireland where he spent a weekend with Irish Nationalist MP and chess addict John Howard Parnell, whose love of chess is mentioned on several occasions in James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Here’s a game from a Dublin simultaneous display.

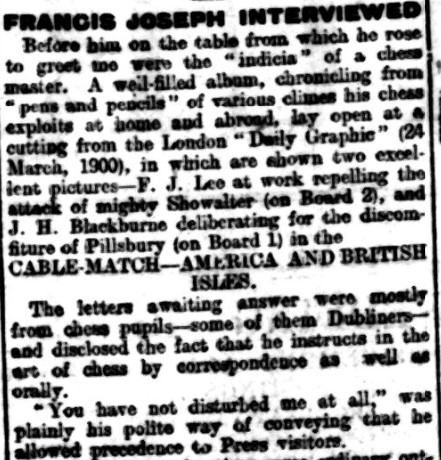

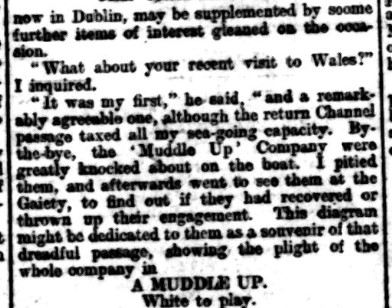

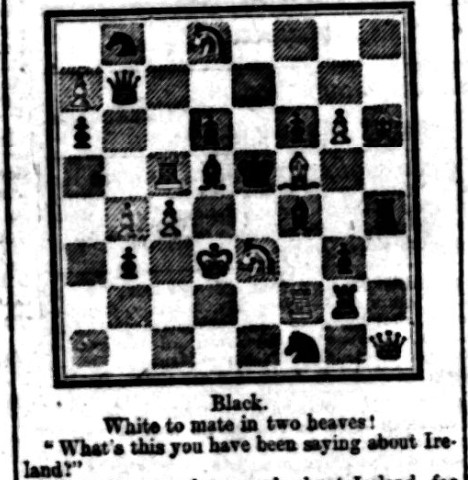

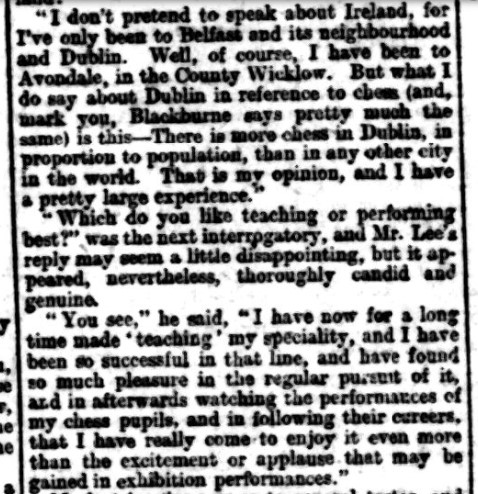

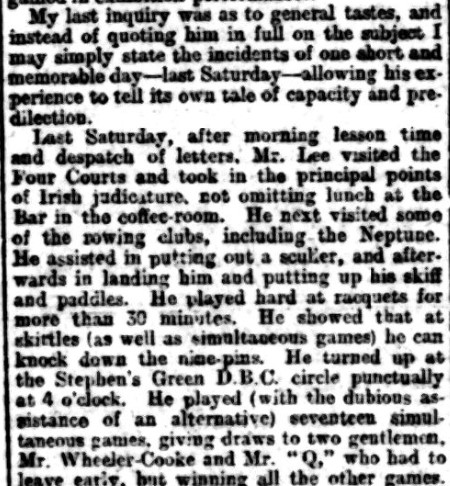

Lee was also interviewed by the Dublin Evening Herald (16 March 1901).

In April he returned to London where he was placed on Board 3 in the Anglo-American cable match, drawing his game with John Finan Barry. That summer there was another match against Richard Teichmann, which he lost by 5½ to 2½.

Lee continued touring in England into 1902, when he played on Board 4 in the Anglo-American Cable Match. Playing white against Albert Beauregard Hodges, he seemed ill at ease in an IQP position, losing the exchange and, eventually, the game.

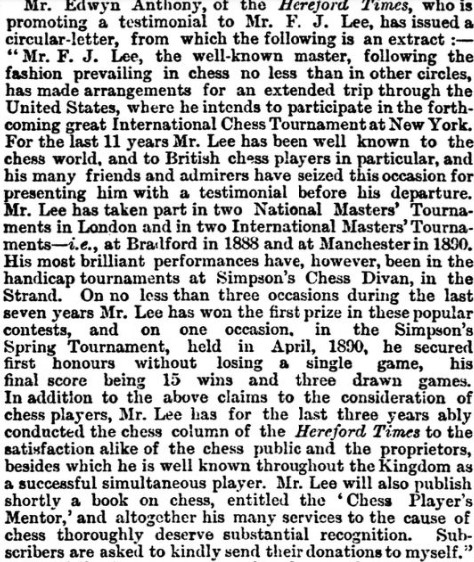

Then, in April, there was an announcement.

Eastern Daily Press 02 April 1902

Eastern Daily Press 02 April 1902

But he had time for an Easter party before he left, having fun with some distinguished friends.

Except that he never reached Australia, instead stopping off in South Africa, where his brother George was living. By June it was reported that he was giving simultaneous displays and playing exhibition games in Cape Town.

This game was played against two of South Africa’s strongest players, Abraham Michael and Max Blieden, playing in consultation.

He then visited Pretoria and Johannesburg, where, in December, he was appointed Chess Editor of the Rand Daily Mail. He seemed well and truly established in a new country of residence.

Fairly substantial sponsorship for the time and place, I would have thought. Needless to say, he won first prize with a score of 8/9, followed by Blieden on 7½ and Michael on 6½.

In this game his opponent missed a chance to activate his queen on move 31 before ill-advisedly trading queens into a lost bishop ending.

Nice work if you can get it. Organise a tournament, find a sponsor and then, because you’re the strongest player around, win it (the first prize was £55) yourself.

But then:

(There are quite a few instances of his being referred to as JF Lee rather than FJ Lee.)

Back in England again, he spent the autumn touring clubs in the south west of the country. In January 1904 he was at the other end of England, in Carlisle, before travelling down to Brighton for a 9-player tournament in February.

Here, he shared second place with 5½/8 with the young German player Paul Saladin Leonhardt, resident in London at the time, a point behind Reginald Pryce Michell.

Here’s his win against Leonhardt.

In March Lee was appointed umpire of the Oxford v Cambridge match, and was called upon to adjudicate an unfinished game when time was called. Summer was a busy time, with two tournaments to play in.

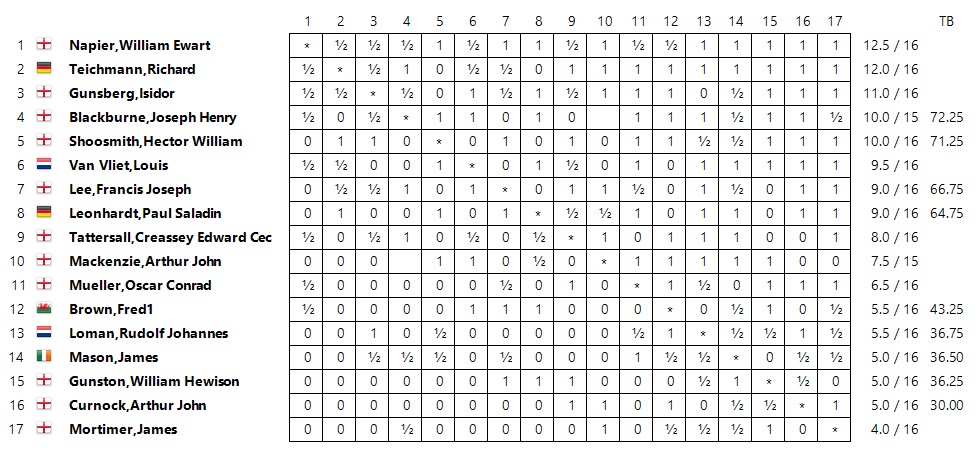

The City of London club organised an event starting at the end of July featuring many of the top players then resident in England. With the Germans Teichmann and Leonhardt, along with Dutchmen van Vliet and Loman it had quite an international feel to it.

Lee’s score of 9/16 was round about a par result for him.

The great veteran Blackburne opened 1. a3, and Lee was able to build up one of his trademark slow kingside attacks.

He was fortunate to win an exciting game against endgame (and carpet) expert Tattersall.

At this time he liked to transpose from the Exchange Caro-Kann into the Scandinavian by capturing with his queen on d5. It didn’t always work out, but here, against one of the weaker players in the event, it proved effective.

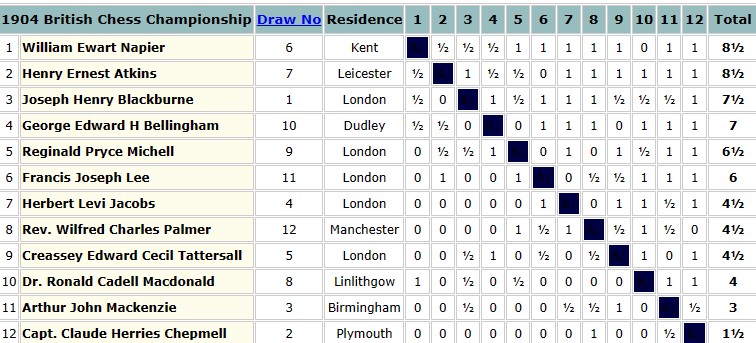

Just a week later, the first British Chess Championships took place in Hastings. Lee was selected for the top section, so had to make another trip down to the Sussex coast.

His result was again what he would have expected. On retrospective ratings he finished below those rated above him, and above those rated below him, but he did have wins against Atkins and Michell to his credit.

In the first round Mackenzie carelessly blundered into a queen sacrifice.

Lee annotated this game for the British Chess Magazine. He commented after Black’s 24th move that Black should have played Qf7, but White’s advantage was probably sufficient to win. Stockfish, as you’ll see, is of a different opinion.

This is the key position from Lee’s game against Atkins. Atkins miscalculated by playing 22… Bxe1? (Qxb7 is only slightly better for White) 23. Bxc8 Rd8 24. Bc5 Qc7 25. Bxe6 and Black resigned as he’s going to end up a piece down.

His win against Michell is well worth looking at.

Later that year, Lee undertook another tour of South West England, but 1905 started quietly. He was selected to take part in the Anglo-American cable match, but this was called off at short notice due to broken cables.

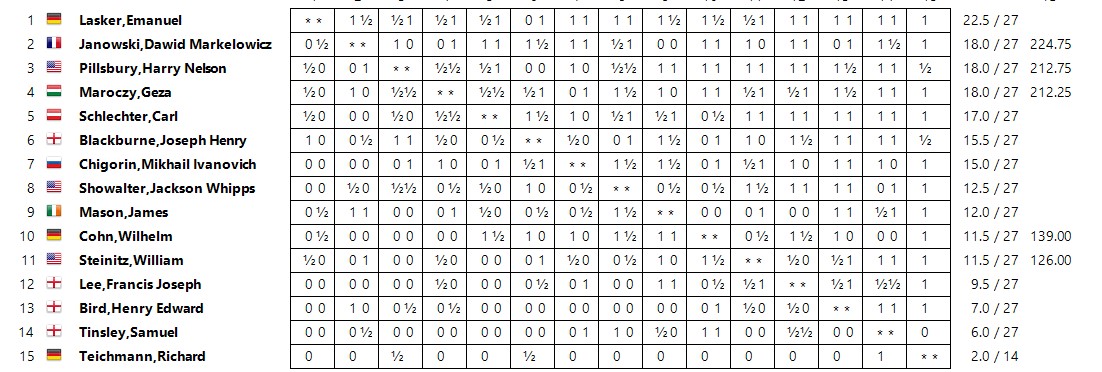

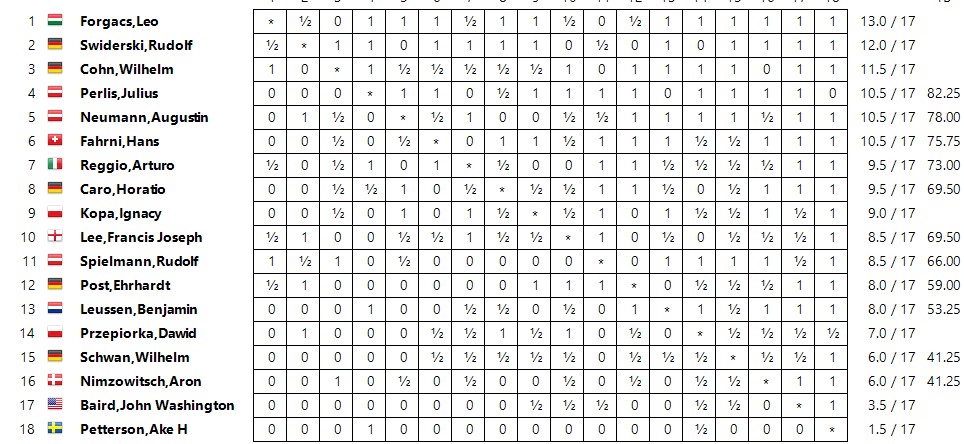

That summer, rather than playing in the British Championship, he took part in his first continental tournament, playing in the Masters B section of a massive event in Barmen, Germany.

His 50% score was again about par for the course, but, typically, he performed as well against the top half as he did against the bottom half. The two most familiar names to you, I guess, would be Spielmann, finishing level with Lee, and Nimzowitsch, who had a poor result. Both were young men who would do much better in future.

His win against Spielmann, using his favourite Caro-Kann Defence (I’m sure Horatio Caro himself would have been delighted) was an excellent game.

His game against the Italian representative was also very typical of his style.

In this game against a German master, though, he was on the wrong side of a spectacular miniature. Sadly, Post would later become the Nazis’ leading chess organiser.

Here, against a Dutch opponent, he escaped from a lost position by sacrificing a rook for a perpetual check.

In the last round he won another good game against the second place finisher.

You’ll see from these games that Lee was capable of producing interesting games from openings which might be considered slow, but not necessarily dull.

By November he was touring in Scotland, announcing that he was planning an extensive tour of the Colonies in the new year.

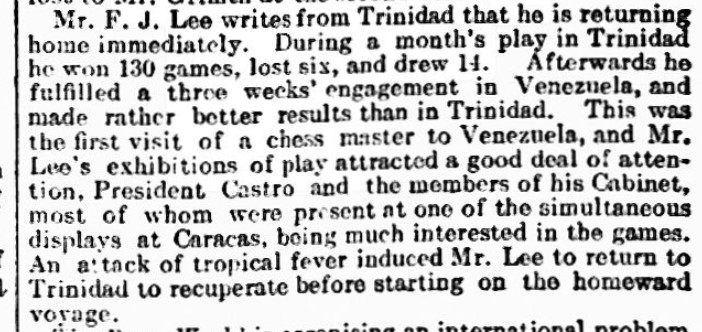

This time he ended up visiting Trinidad and Venezuela.

The visit to Trinidad may well have been instigated by the chess-playing Bishop of Trinidad and Tobago, John Francis Welsh. They met eleven times during Lee’s visit, mostly in simuls, with each player winning five games. Here’s one of the Bishop’s wins, in which he opted for the Lesser Bishop’s Gambit (my source names it the Limited Bishop’s Gambit, known in London, apparently as the Circumcised Bishop’s Gambit).

My source suggests Lee resigned in a lost position as 26… Ne3 would have been winning. Stockfish continues 26… Ne3! 27. Ne6! Nxf1 28. Rxf1 Qd7 29. Nxf8 Qxg4+ 30. Qg2 Qxg2+ 31. Kxg2 Rxf8 when Black is a pawn up in the ending but White should probably be able to hold the draw.

Lee had entered the 1906 Ostend megatournament, but was forced to withdraw for health reasons. Some reports suggested he was, for a second time, planning to visit Australia, but was now unable to do so. However, he had recovered in time to take part in the 3rd British Championships, which took place in Shrewsbury that August.

A score of 7/11 was enough for a share of third place: an excellent result considering his recent health problems.

Against Mercer his pet Stonewall/London formation again led to a winning kingside attack.

Here’s another example: it’s striking that even a strong player like Palmer didn’t really understand what was happening and eventually perished down the h-file.

At the prizegiving, both Lee and Blackburne were presented with purses of gold for their services to chess.

In the autumn of 1906 and early 1907 he toured the north of England, Scotland and Ireland, including spending a week with the Edinburgh Ladies Chess Club. By February 1907 he was back in London, taking board 6 against Albert Whiting Fox in the Anglo-American Cable Match, back after a three year absence.

This was a long and well-played draw, but Lee missed an opportunity on his final move.

Fox (Black) had just played 65… Ke5-d5? instead of the correct fxg2. Now Lee missed the chance to play 66. gxf3! which should secure the full point because the pawn ending after 66… Bxf3 is winning.

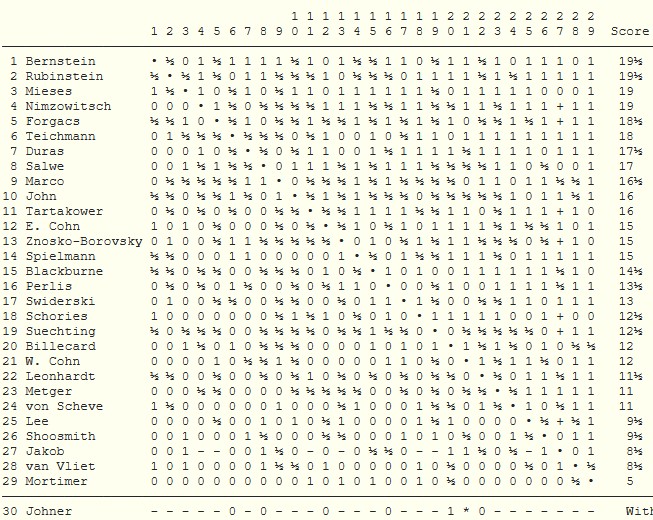

By May he was well enough to cross the channel to Ostend, where another mammoth tournament was being held. The format was slightly more comprehensible than the previous year. A grandmaster section where six players (Tarrasch, Schlechter, Janowsky, Marshall, Burn and Chigorin) played each other four times, a 30-player all play all master section, three amateur sections and, like the previous year, a Ladies tournament. Lee was placed in the master section, which was reduced to a mere 29 players when Paul Johner withdrew after 7 rounds. Another player, Jacob, withdrew towards the end.

Here’s what happened.

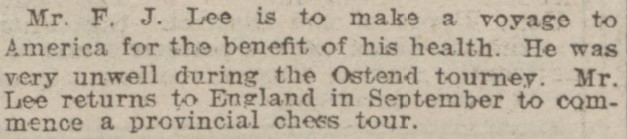

Lee’s performance in such a strong field was only slightly disappointing, and he was in poor health again during what must have been a tiring event.

The players castled on opposite sides in this game, and Lee’s attack proved more successful.

This is probably Lee’s best known game, which will be familiar to readers of Nimzowitsch’s My System.

Lee’s opponent in this game was a German master who spent a lot of time in England before the First World War.

Here’s another game you might have seen before. Fred Reinfeld anthologised it in A Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces.

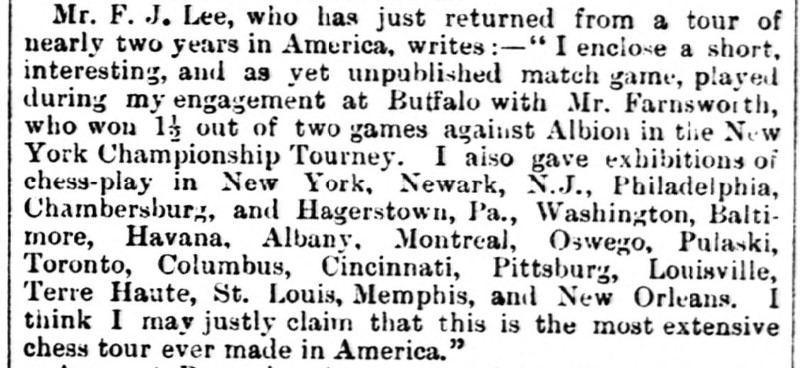

No sooner had he returned from Ostend than he was off on his travels again.

After spending time in Canada he returned, again visiting the north of England, Scotland and Ireland. His tour continued into the new year, but in May 2008 he returned to tournament play in a small tournament in Sevenoaks, Kent, where he was also called upon to give a simultaneous display.

The top section was split into two sections. Lee played in the A section, which was won by the future Sir George Thomas on 5½/6, two points clear of Lee, Shories and Muller, who shared second place.

He won this game with a stock queen sacrifice, but also missed some earlier tactical opportunities.

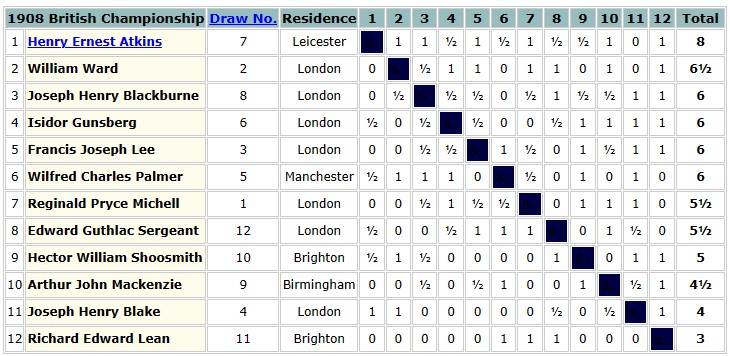

Then it was on to the British Championships, held that year in Tunbridge Wells, Kent. Lee’s score of 6/11 was enough for a share of third place in what was, with the exception of Atkins, a closely fought contest.

A mistake in this position against Ward cost him a half point which would have left him, rather than his opponent, in the silver medal position.

In this exciting position 34… c2 might have led to a perpetual check for White, but Lee erred with 34… Qe7?, and had to resign after the beautiful 35. Bf7!.

With his slow style of play, Lee wasn’t noted for winning miniatures in serious play, but here his opponent (whom I really ought to write about sometime) blundered on move 19, resigning two moves later.

His game against Shoosmith reached an unusual ending when Black, in a blocked position, sacrificed two minor pieces for four connected passed pawns. Both players missed chances, but it was Shoosmith who made the final error.

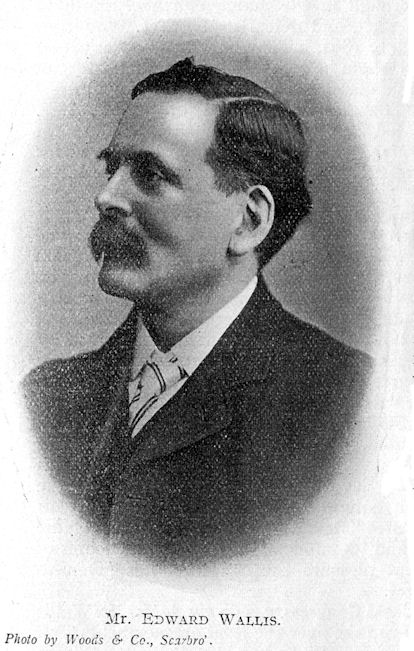

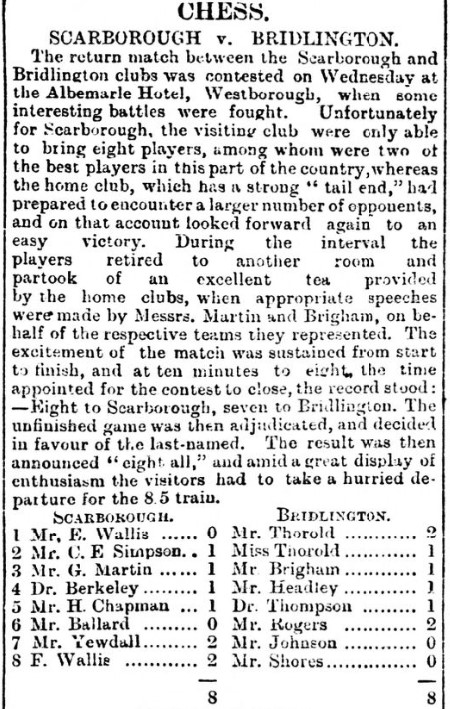

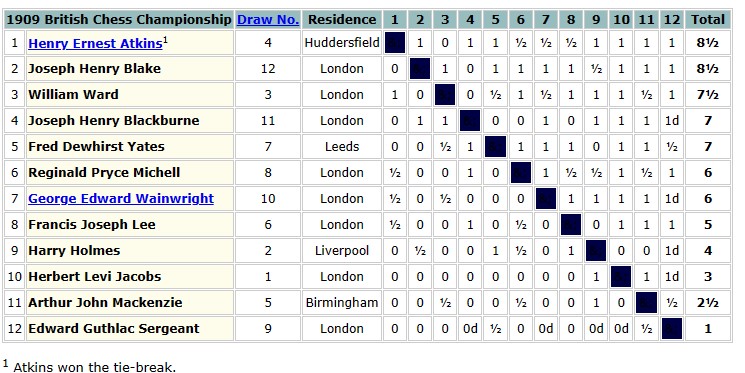

This was a quiet period in Lee’s life – perhaps he had further health problems – but he did visit Bradford in January 1909. Nothing more was heard of him until August when he was back in Yorkshire for the British Championships, held that year in Scarborough.

A score of 5/11 in a strong field was again a more than respectable performance, especially as he was clearly ailing in the second week.

Let’s look at his last three games.

In Round 9 he won a good game against Mackenzie, helped by a blunder on move 38.

In Round 10 he played his favourite Caro-Kann too passively, and Blake, gaining revenge for his defeat the previous year, used his space advantage to engineer a brilliant finish.

In the last round, the fast improving Yates took apart another of his favourite openings, the Stonewall Attack, concluding with an unstoppable Arabian Mate.

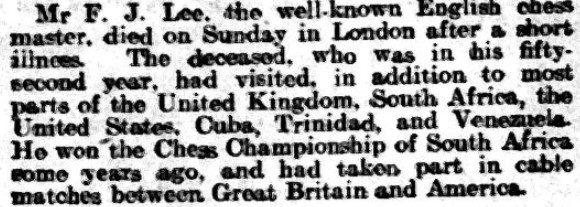

Then, just three weeks later:

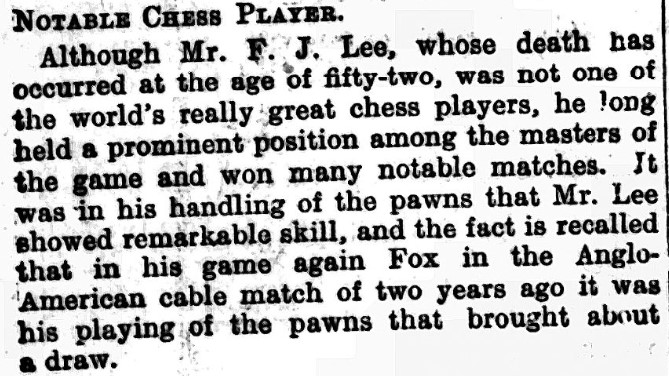

“… not one of the world’s really great chess players”. Not very generous for a death notice, I would have thought.

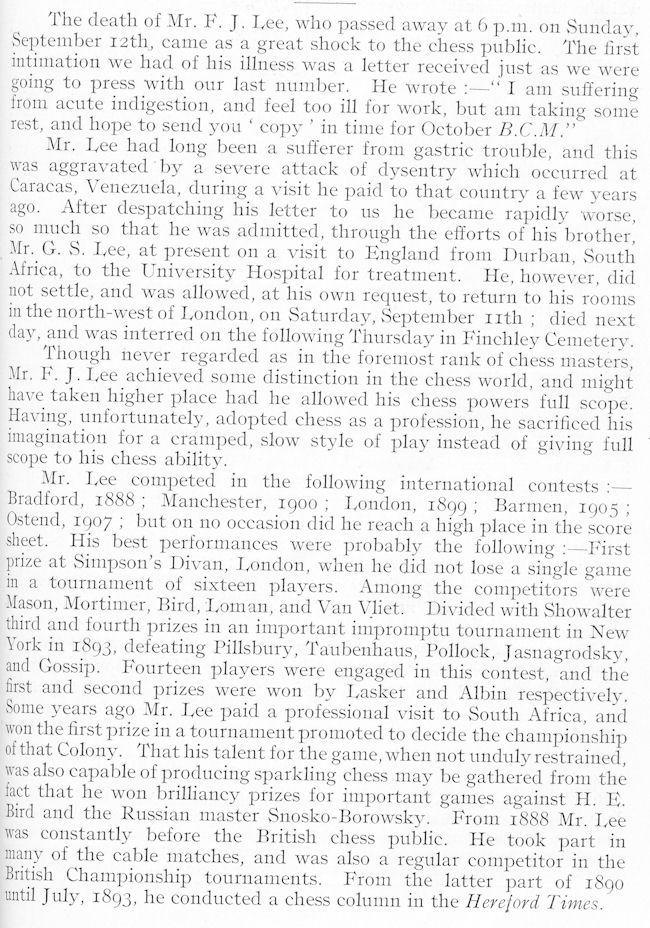

He regularly annotated games for the British Chess Magazine, who had rather more to say.

They might also have been more generous about the premature death of a valued contributor.

Again: “… never regarded in the foremost rank of chess masters…”: harsh but true, I suppose.

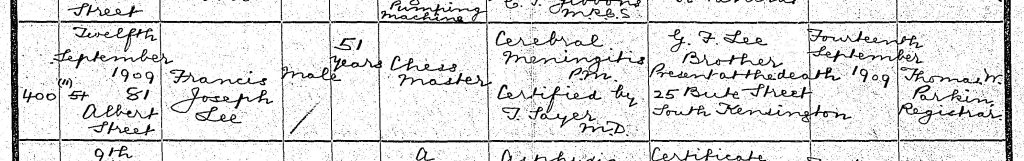

The obituary spoke about his gastric trouble, and he had also had lung problems in the past, but his death certificate reveals that neither was his cause of death.

Cerebral Meningitis (is there any other type): to the best of my knowledge indigestion isn’t a symptom.

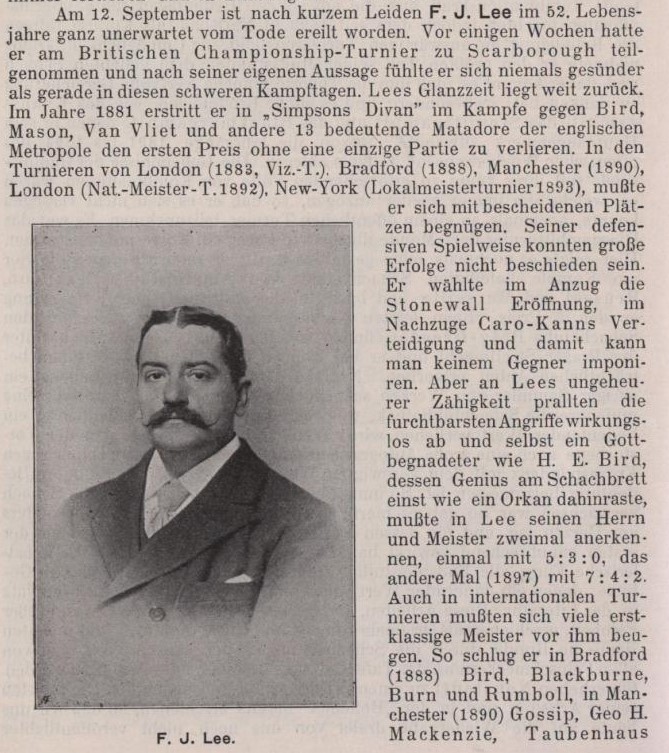

The Wiener Schachzeitung provided a long and rather more sympathetic obituary.

Not very accurate, though. The 1881 Simpson’s Divan event seems to have been the 1890 event misdated, although there were 19, not 14 players and it was a handicap tournament. It was the short-lived Henry Lee (no relation as far as I know) who played in the London 1883 Vizayanagaram Tournament, not our man Francis Joseph Lee.

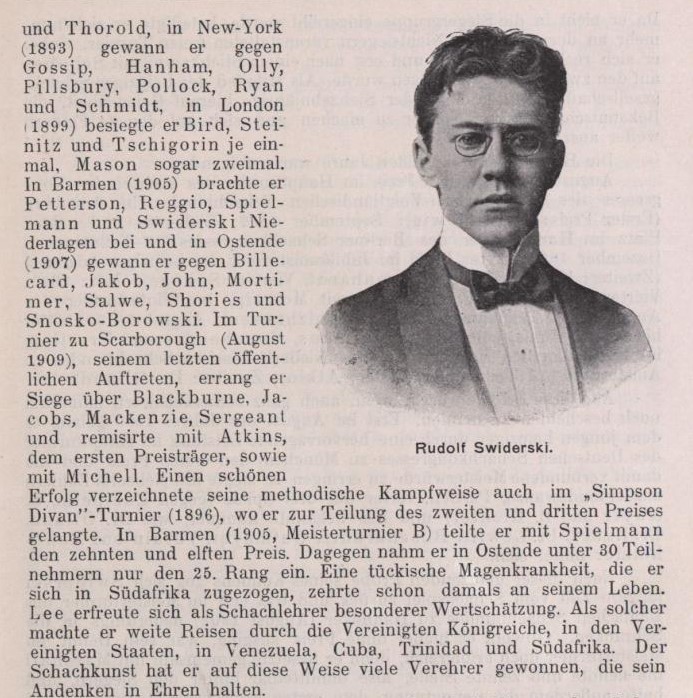

The layout could perhaps also have been improved. Swiderski died at the same time (by his own hand) and his obituary was immediately below that of Lee.

Let’s return for a moment to the BCM obituary: “Having, unfortunately, adopted chess as a profession, he sacrificed his imagination for a cramped, slow style of play instead of giving full scope to his chess ability.”

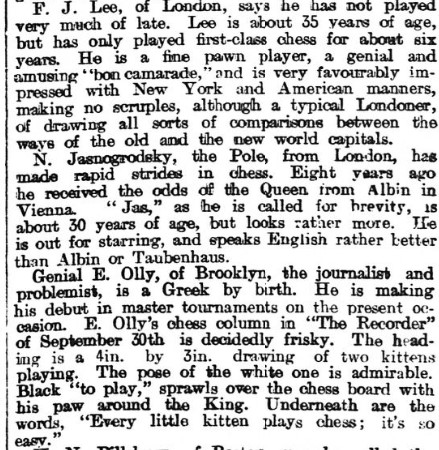

This suggests two reasons why he wasn’t universally popular. He was a professional at a time when professional sportsmen (they always were men in those days) were scorned, and he preferred playing closed rather than open positions.

I consider this rather unfair. Although he played gambits in simuls and informal games, he was very much a player in the modern style, influenced in part by Steinitz. With White he favoured mostly d-pawn openings: the Stonewall and London Systems, often combined, as well as Queen’s Gambits and types of Colle System. With Black he defended against 1. e4 with, at various times, with the French, Caro-Kann and Scandinavian Defences. Understanding of closed positions, although they had been played by the likes of Philidor, La Bourdonnais and Staunton, was still rudimentary compared with today’s grandmasters, but it was the experiments of players like Lee which played an important role in the development of chess ideas.

You’ll also see that, although his games, and those of other similarly inclined players of his day, could descend into meaningless woodshifting, there were also positive ideas, in particular in building up slow kingside attacks. His games were often not short of excitement, but that was more likely to come at move 50 than move 15. I’d put it to you that his obituarist (Isaac McIntyre Brown?) failed to appreciate his games fully.

Of course he had his faults: he was prone to tactical oversights and, against the top players of his day, didn’t always understand what was happening positionally, but he was still in the world’s top 100 players for about 20 years. His fragile health must also have had an impact on his results, and his interview above suggests that he was temperamentally more suited to teaching than playing.

It’s interesting to compare his life with that of a journeyman chess professional today. He was probably never very well off, but he had various sources of revenue: teaching and lecturing, simultaneous displays, exhibition games, writing and journalism, and also sponsorship. An article by Mieses in the August 1941 BCM about former Prime Minister Andrew Bonar Law tells us that he was kindly disposed towards Lee and did a good deal quietly for his professional support. One would imagine that Lee was similarly supported by the likes of JH Parnell and the Bishop of Trinidad and Tobago. In his tours of chess clubs he was seen as being a friendly and courteous opponent.

The Cheltenham Chronicle (13 September 1919), writing just a decade after his death, referred to him as ‘another chess professional, now little remembered’. He’s certainly very little remembered or written about today.

I’d suggest that Francis Joseph Lee is very much worthy of your attention. Here was a man who clearly loved chess, and, despite ill health, devoted more than twenty years to promoting his favourite game throughout the British Isles, and in many other parts of the world as well. While he wasn’t one of the greatest players of his day he also produced some fine chess, along the way experimenting with new openings, some of which are now, a century and a quarter on, now back in fashion.

I hope you’ve enjoyed learning more about his life and looking at some of his games. Do join me in drinking a toast to Francis Joseph Lee, and also join me again soon for some more Minor Pieces.

Sources and references:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archive

Wikipedia

chessgames.com: FJ Lee here

ChessBase/MegaBase 2024

Stockfish 16

EdoChess (Rod Edwards): FJ Lee here

British Chess Magazine (thanks to John Upham)

Wiener Schachzeitung