Continuing my series about Arthur Towle Marriott’s Leicester opponents, we reach W Withers, almost certainly William. Apologies to those of you who’ve been eagerly awaiting this article, but I’ve been busy on other projects. You’ll find out more later.

Great song, and I hope you all have a lovely day, but this wasn’t William Harrison Withers Jr.

W Withers, sometimes WJ Withers (or were they two different people?), first appeared in Leicester chess records in 1874, when he was elected Club Secretary, and continued his involvement, representing Leicester, and the smaller club, Granby, in matches against other Midlands towns and cities, until 1900. But who was he?

Withers is a surprisingly common name in the East Midlands. One of James Towle’s fellow Luddites bore the name William Withers, but his family were from Nottingham rather than Leicester and seem not to have been related to the chess player.

There were several gentlemen named William Withers in Leicester at the time. We can assume, because, as a young man he was the club secretary, that he came from an educated background. The only W Withers who fits the bill is William John Withers, who lived most of his life in Leicester, although his birth was registered in the St Pancras district of London in the second quarter of 1853, and who died in the Harrow/Hendon area on 23 December 1934.

William’s father, George Henry Withers, was the son of John Withers, born in the chess town of Hastings. John had a varied career. Originally a lace maker, he joined the police, rising to the rank of inspector. He then went to work on the railways, first as a station master, and then as a railroad contractor, before becoming a commission agent, and, finally, a clerk at a coal wharf. Was there any job he couldn’t turn his hand to? In between times, he found time to father eight children: seven sons and a daughter. Not for the first time in Minor Pieces, his seventh son was named Septimus.

George Henry Withers was John’s eldest son. Born in about 1830, he followed his father into the railways, a very common occupation at the time. When he married Mary Ann Caunt in 1849, he was a railway clerk, living in the Leicestershire town of Melton Mowbray, famous for its pork pies. He was described as being ‘of full age’: it’s not certain that this was true. By the 1851 census he was a station master living in Orston, Nottinghamshire.

This was presumably Elton Station, now called Elton and Orston, half way between those two villages, which had only opened to passenger traffic the previous year. In 2019/20, it was the second least used station in the country.

He didn’t stay there long. By 1853, when our man William was born, he was in the St Pancras area of London, perhaps working at one of the London railway termini: St Pancras itself, Kings Cross next door, or nearby Euston.

Just a few months later he’d moved again. Sadly, the death of his oldest child, Albert, was recorded in Grantham, and he was buried in the nearby village of Great Gonerby, whose inhabitants are known as ‘Clockpelters’, from their habit of trying to strike the face of the church clock with stones or snowballs.

We pick him up again in 1857, when, now working as a bailiff, he was appointed a Freeman of the City of Leicester. Later census records see him working as a commission agent, an accountant, a bookkeeper and a gardener. Like his father, a many of many skills and occupations.

It’s more than time to find out more about William John Withers. His first job was as a clerk in a coal office, and when he married in 1873, he was still in the same job. His wife, Annie Clarke, was the daughter of a house painter, the same occupation that was followed by my grandfather Tom Harry James. Their first child, Horace, was born the following year, when William was also elected to the post of Secretary of Leicester Chess Club. It seems that he didn’t stay in that post long, though.

On 29 October 1880, he represented Leicester in a match against a visiting team from Nottingham Chess Club, where he faced Minor Pieces hero Arthur Towle Marriott.

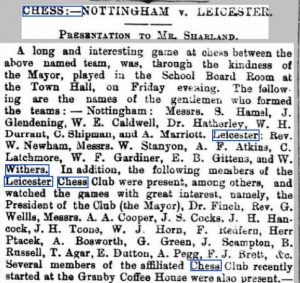

The Leicester Chronicle (6 November 1880) reported what sounds like a convivial affair. Half way through, they all stopped playing to witness a presentation to Mr Sharland, the Leicester Club Secretary, who, in less than five years, had increased the club membership from 18 to 61. Various speeches were made before the gentlemen of Leicester and Nottingham resumed their games.

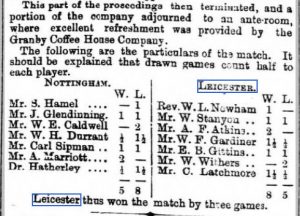

It seems that only one game was played on top board, while the other boards played two games each. Arthur Towle Marriott, the only Nottingham player to win both his games, seems to have been playing on too low a board.

Here’s his game with White.

The game followed well known (at the time) Evans Gambit theory for some way. Black’s 7th move is brave: 7… Nge7 and 7… d6 are most often played, but the engines like 7… Nf6 8. e5 d5. 10… b5 was also a bold choice: again 10… Nge7 would have been more circumspect. Marriott had stronger, but difficult, options on move 13, but his choice proved successful when the Leicester man blundered horribly in reply.

Three weeks later the Leicester chessers visited Nottingham for the return match, this time with a much weaker team. Mr Bingham’s restaurant provided an excellent supper, with speeches and toasts, before play started. Arthur Marriott, after his success in the earlier match, had been promoted to board 3, and again found himself facing William Withers.

The Nottingham Journal (27 November 1880) reported on an overwhelming victory for the home team. 11½-2½ was very different from the earlier 5-8 defeat.

These matches appear to have been social events rather than the competitive inter-club matches with which we’re all familiar. Although there was considerable interest in the result, the eating and drinking seemed just as important. Perhaps that’s how club matches should be.

Again, we have the game where Marriott played White against Withers.

This time, Withers chose to avoid the Evans Gambit, but playing 3… Nf6 without knowing the theory isn’t a good idea. Even then, it was known that 5… Nxd5 wasn’t best, giving White a choice of two strong options, 6. d4 and that primary school favourite, 6. Nxf7, the Fried Liver Attack.

Engines now confirm that 8… Ne7 in the Fried Liver is losing, but 8… Nb4 might just keep Black in the game. Marriott missed a couple of better moves, but Withers panicked on move 13, losing even more quickly and horribly than three weeks earlier.

By today’s standards, the chess of William John Withers makes a poor impression: a player with a patchy knowledge of opening theory along with tactical vulnerability.

Note that A F Atkins, who played for Leicester in these matches, was Arthur Frederick Atkins, originally from Coventry, and no relation to the great Henry Ernest Atkins, about whom more next time.

By now William had a new job: the 1881 census told us he was a bookseller in Loseby Lane, Leicester, only a few yards away from where a later and stronger Leicester chess player would, several decades later, also run a bookshop. You may well meet him in a future article. He was also just a short walk from what is now De Montfort University, the new home of the English Chess Federation library and also, as it happens, my alma mater.

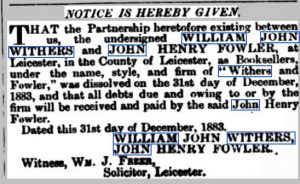

An announcement in the Leicester Journal (5 January 1884) suggests that his bookselling business hit a problem.

It was time for him to turn over a new leaf. By 1891 he was an antiques dealer, having moved just round the corner to Silver Street, and doing well enough to employ a servant. The 1901 and 1911 censuses told the same story: in the latter year he styled himself a ‘dealer in genuine antiques’.

At some point after that, perhaps after the death of his father in 1913, he moved to London. The 1921 census, due for release next January, will reveal more.

We can pick William up again in 1932, when he made his last will and testament, granting generous bequests to his children and grandchildren. Still working as an antique dealer, his address was given as 48 George Street, Manchester Square, WC1, only a few minutes’ stroll from 44 Baker Street, where, had he been able to travel through time, he’d have been able to stock up on the latest chess books.

His antique dealing had clearly been very successful. He died in 1934, and probate records reveal that he left effects to the value of £15,240 17s 9d, which, depending on how you calculate it, amounts to anywhere between one and seven million pounds in today’s money.

So there you have it. While his chess playing didn’t impress, he played an important role in chess life in Leicester. Away from the board, in both business and family life, he seems to have done very well for himself. Well played, William John Withers!