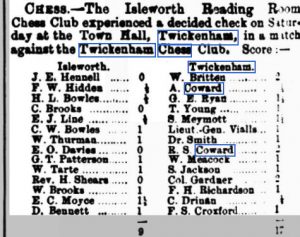

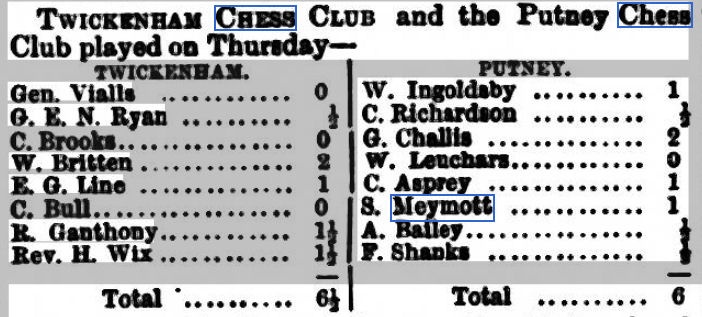

You saw this result in my recent article about the Coward family. There are some other names of interest in this Twickenham team.

On board 5 for Twickenham was Sydney Meymott. Many players, like Arthur and Randulph Coward, only play competitive chess for a few years before moving on to another stage in their lives. There are others for whom chess is a lifelong obsession: the Complete Chess Addicts (now that would make a great book title!), and Sydney was one of those, with a chess career lasting almost half a century.

He came from a distinguished family. His grandfather, John Gilbert Meymott was a prominent lawyer, and his father Charles Meymott a doctor whose other interests included cricket and chess.

Charles played two first class cricket matches for Surrey, but without success. Against the MCC in 1846 he was dismissed without scoring in the first innings and made 4 not out in the second innings. Against Kent the following year he failed to trouble the scorers in either innings. He also failed to take any wickets in either match.

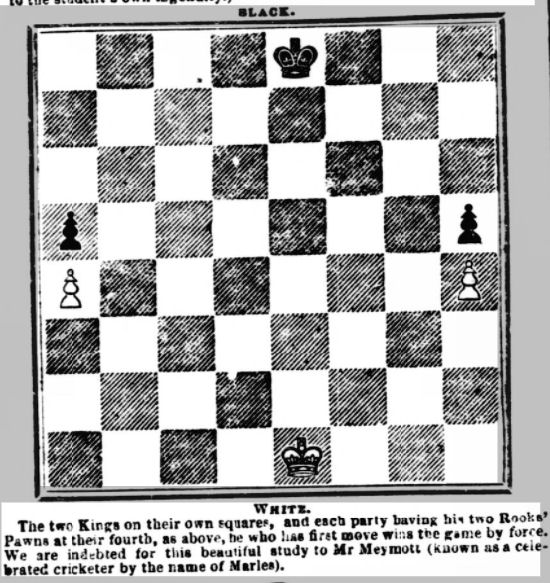

In 1848 he submitted a ‘beautiful study’ to Bell’s Life, as you can see below.

A few weeks later the solution was published, failing to provide any moves but just saying that White will win a pawn and the game.

But as you can demonstrate for yourself (or verify using tablebases) this is complete nonsense: the position is drawn with best play.

A celebrated cricketer who composed a beautiful study? I think not.

Earlier in 1848, he’d submitted a mate in 4 to the Illustrated London News, which was at least sound, if not very interesting. You can solve it yourself if you want: the solution is at the end of the article.

Problem 1:

#4 Illustrated London News 12 Feb 1848

In about 1859 Charles, his wife Sarah (née Keene, no relation, as far as I know, to Ray) and their three daughters (a son had died in infancy) emigrated to Australia, where his brother Frederick was a judge. The family must have been well regarded there. If you visit the suburb of Randwick today, not far from Coogee Beach, you’ll find a residential road there named Meymott Street, with Frederick Street running off it.

From there Charles submitted another mate in 4, slightly more sophisticated this time.

Problem 2:

#4 Illustrated London News 26 Nov 1859

The following year, Sarah gave birth to a son, who was given the name of his home city: Sydney.

Charles Meymott had started out in conventional medicine but at some point he had converted to homeopathy. You can find out a bit more here, although some of the links no longer work.

Charles died in 1867 at the age of 54, and his widow and children decided to return to England. I wonder if he’d been able to teach his young son how the pieces moved.

In 1871 Sarah and young Syd were living in Queen Street (now Queen’s Road) Twickenham: perhaps the girls only returned to England later.

By 1881 the oldest girl had married and moved to Scotland, but Sarah and her three youngest children were now at 4 Syon Row, Twickenham, right by the river.

The road is so well known that a rather expensive book has been written about it.

It was from there, then that, at some point in 1883 or 1884, the 23-year-old Sydney Meymott joined Twickenham Chess Club.

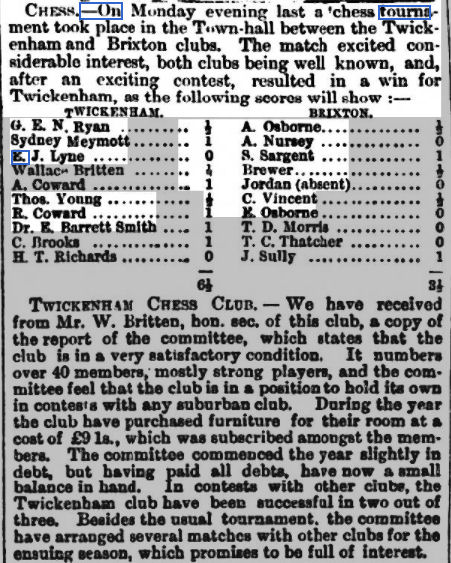

Here he is again, in a match played in October, now on Board 2 against Brixton. You’ll see George Ryan on top board, with Wallace Britten and the Coward brothers lower down. Young Edward Joseph Line (not Lyne), born in 1862, who had played for Isleworth against Twickenham earlier in the year, was on Board 3, although he was one of only two Twickenham players to lose.

If you’re interested in this part of the world, you might want to check out my good friend Martin Smith’s new book Movers and Takers, a history of chess in Streatham and Brixton. A review will be appearing on British Chess News shortly.

Syd had decided on a career as a bank manager, and his training would have involved working at different branches gaining more experience before managing a larger branch himself. This was perhaps to be his last appearance for Twickenham, but we’ll follow the rest of his life in this article.

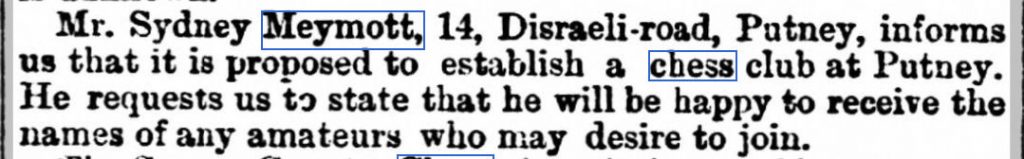

Just a couple of weeks later he wrote to the Morning Post:

Disraeli Road is conveniently situated just round the corner from Putney Station, with its frequent trains to Waterloo. Impressive houses they are too: young Syd was doing well for himself.

The new chess club in Putney rapidly became very successful. Inevitably, they invited Blackburne to give a blindfold simul in February 1886: Meymott was the only player to draw.

In December the same year, Sydney issued a challenge to his old club, with Putney winning by 5 games to 3.

Here’s what happened in the return match in the new year.

He was soon on the move again, leaving the good chess players of Putney to their own devices. Without their leading light the club struggled on for a few years before apparently folding. This time, Syd’s work took him to Honiton, Devon, where again he started a chess club. By now he was writing regularly to the Morning Post, solving their problems and sometimes submitting problems of his own – which were not considered suitable for publication.

In this game he demonstrated his knowledge of Légal’s Mate. (In this and other games in this post, click on any move to obtain a pop-up board and play through the game.)

Source: Morning Post 17 Dec 1888

Here, he was able to show off his attacking skills in the Evans Gambit, giving rook odds to another semi-anonymous opponent.

Source: Western Morning Post 26 Feb 1891

By now it was time for Sydney to move on again, this time back to West London, to Ealing the Queen of the Suburbs, where he’d remain for the next 40 years. He’d eventually become the Manager of the Ealing Broadway branch of the London and South Western Bank.

This time he didn’t need to start up a chess club: there already was – and still is – one there, founded in 1885. As a bank manager, he was soon cajoled, as bank managers usually are, into taking on the role of Honorary Treasurer.

In this game from a local derby against Acton, Black’s handling of the French Defence wasn’t very impressive, allowing Meymott to set up a Greek Gift sacrifice.

Source: London Evening Standard 25 Nov 1895

Meymott commented: … it may interest some of the younger readers and stimulate them to ‘book’ learning, the game being a forcible example of the utility of ever being alert to the well-known mating positions… Sixteen years later, the young Capablanca played the same sacrifice in the same position. Perhaps he’d read the Evening Standard. Learning and looking out for the well-known mating positions is still excellent advice today.

In May 1896 Sydney made the headlines in the local press for reasons unconnected with either chess or banking. He was one of those stuck for 16 hours on the Great Wheel at Earl’s Court, and was interviewed at length about his experiences by the Middlesex County Times (30 May 1896 if you want to check it out). Fortunately, a lady in his car managed to let down a reel of cotton, so that they were able to receive refreshments, in the shape of stale buns and whisky and soda, from the ground.

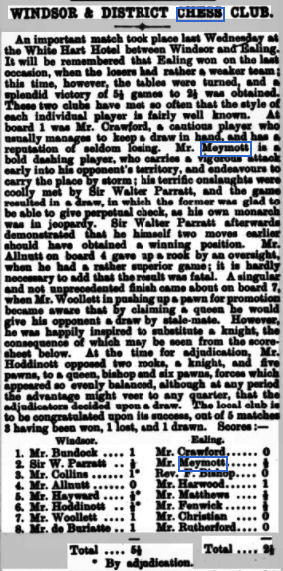

A match against Windsor in 1897, where he was described as a ‘bold dashing player’ saw him pitted against an illustrious opponent in Sir Walter Parratt, organist and Master of the Queen’s Musick, and a possible subject of a future Minor Piece.

Life at Ealing chess club continued with a diet of inter-club matches, internal tournaments and simultaneous displays, with Syd often successful in avoiding defeat against the visiting masters.

In 1899, approaching his forties, he married Annie Ellen Nash. They stayed together for the rest of his life, but had no children.

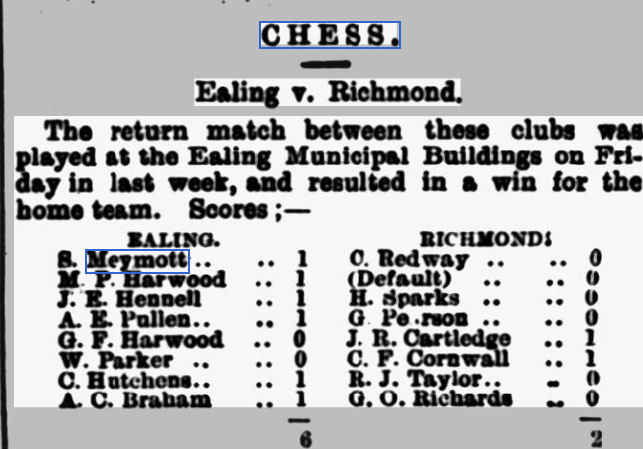

In this 1902 match against Richmond, Ealing scored an emphatic victory helped by the non-appearance of Richmond’s board 2. A future series of Minor Pieces will introduce you to some of the Richmond players from that period in the club’s history.

As he settled into comfortable middle age, life continued fairly uneventfully for Sydney and Annie. The 1911 census found them at 18 Uxbridge Road, Ealing, which seems to have been in the town centre, possibly above the bank.

Many clubs closed down during the First World War, but Ealing, with Sydney Meymott still balancing the books, kept going. Electoral rolls from the 1920s record Syd and Annie at 23 Woodville Road, Ealing, and very nice it looks too. A spacious detached house just for the two of them. In 1921, he was in trouble with the law, though, receiving a fine for not having his dog muzzled.

At some point in the 1920s, Sydney would have retired from his job as bank manager, giving him more time for chess, and time to resume submitting games for publication. In his sixties, when many players would be thinking about hanging up their pawns, Syd, always the chess addict, took up tournament chess.

Hastings 1922-23 was what might have been Meymott’s first tournament. Unfortunately he had to retire ill with 1½/6 in First Class B section.

In 1925 he visited Scarborough, playing in the Major A section. He won a few games but didn’t finish among the prizewinners.

In 1926, using his favourite French Defence, he managed to beat Fred Yates in a simul. The complications towards the end are intriguing: do take a look.

Source: Middlesex County Times 23 Jan 1926

That Easter Syd took part in one of the First Class sections of the West of England Championship at Weston-Super-Mare, finishing in midfield.

Later the same year, representing the Rest of Middlesex against Hampstead, he played this game against Ernest Montgomery Jellie. White’s 11th move looked tempting but turned out to be a losing mistake: Jellie’s knight was very shaky on d6 and his position soon wobbled.

Source: Middlesex County Times 16 Oct 1926

At this point it’s worth taking a slight detour to consider Meymott’s opponent. Ernest Montgomery Jellie and his wife Emily, who sadly died young, had three Jellie babies. Their daughter Dorothy married Sidney Stone, and one of their sons, Chris, inherited his grandfather’s love of chess.

I knew Chris very well back in the day, when he was involved with Pinner Junior Chess Club, where his son Andrew was one of their star players. Chris was an enthusiast rather than a strong player himself, but Andrew is both. He’s been a 2200 strength player for many years, representing Streatham in the London League as well as his local club, Watford.

You can read much more about the Jellie-Stone connection here (Martin Smith again).

After Christmas 1926, Sydney went down to Hastings where he took second prize in the Major C section with a score of 7/9. Well played, Syd!

On his return, he played this game. This seems to have been in a handicap tournament, where, instead of giving knight odds, the players agreed that Meymott would play blindfold.

Source: Acton Gazette 14 Jan 1927

At Hastings 1927-28 he scored 50% in the First Class B section. Easter 1928 saw him back at the West of England Championships, held that year in Cheltenham, where he galloped to victory in the Class IIB section, scoring 7½/9.

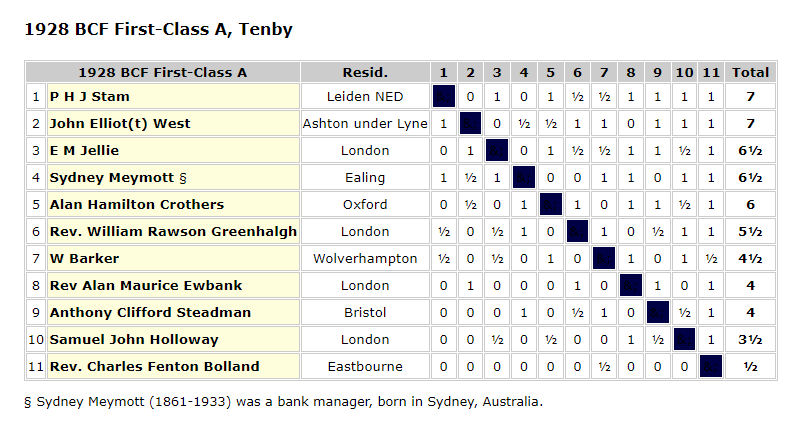

The British Championships in July 1928 took him further west, to Tenby, where he played in the First Class A section, sharing third prize with the aforementioned Ernest Montgomery Jellie on 6½/9, but again beating him in their individual game.

He was back at Hastings 1929-30, where he scored a respectable 5/9 in the First Class B section.

In September 1931 he did what many chess players of that period did: he retired to Hastings, after four decades living and playing chess in Ealing. He was soon playing for his local club.

In a match against Brighton in 1932 his opponent was Kenneth Gunnell, who would much later become, briefly, a rather controversial member of both Richmond and Twickenham Chess Clubs.

That would be one of his last games. On 7 February 1933 Sydney Meymott died at the Warrior House Hotel, St Leonards on Sea.

Writing about Ernest Montgomery Jellie, Martin Smith summed him up beautifully:

But who is he, and why should we be interested? There two reasons that come to mind.

One is that he turns out to be an exemplary specimen of an ordinary decent chesser, the sort often overlooked in histories of the game. He and other enthusiasts like him, then and now, are the body-chessic upon which the chess bug spawns and beneficently multiplies. Stir E.M. Jellie together with the rest and you get the thriving chess culture that we all know: the one that germinates the few blessed enough to rise to the top.

Replace E.M. Jellie with Sydney Meymott, and the same sentiments apply. A good player, but not a great player. For almost half a century a stalwart of club, county, and, later, congress chess. A club treasurer for many years, but in his younger days also a founder and secretary of two clubs.

In these days of chess professionalism, even at primary school level, of obsession with grandmasters, prodigies and champions, we’re at risk of losing the likes of Jellie and Meymott. We should be developing chess culture in order to develop champions, not the other way round. And that celebration of chess culture is one of the reasons why I’m writing these Minor Pieces. My friends at Ealing Chess Club today should certainly raise a glass to Sydney Meymott.

Solutions:

1.

1. Bxg5+ Kg6 2. Bf6+ Kh5 3. Ng3+ Kh6 4. Bg7#

2.

1. Nxd5 gxf3 (1… Rxb5 2. e3+ Kc4 3. Nb6#) (1… Bc3+ 2. Nxc3 Bd5 3. e3+ Kc4 4. Bxd5#) (1… Bxb5 2. e3+ Kc4 3. Nxb6#) 2. e3+ Ke4 (2… Kc4 3. Ndc7+ (3. Nc3+ Bd5 4. Bxd5#) 3… Bd5 4. Bxd5#) 3. c3 Rxb5 (3… Bxd5 4. Bxd5#) 4. Nf6#