You’ve seen this before:

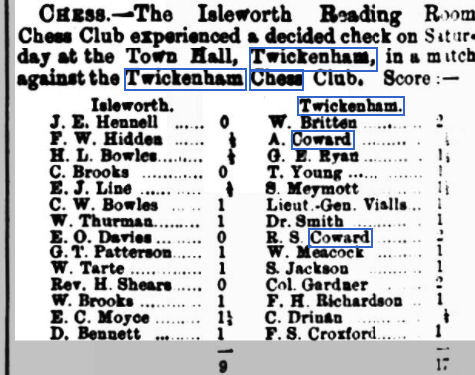

You’ll notice Twickenham fielded two military men in this match.

We need to find out more about them.

The rank of Lieutenant-General is the third highest in the British Army behind only General and Field Marshal: an officer in charge of a complete battlefield corps.

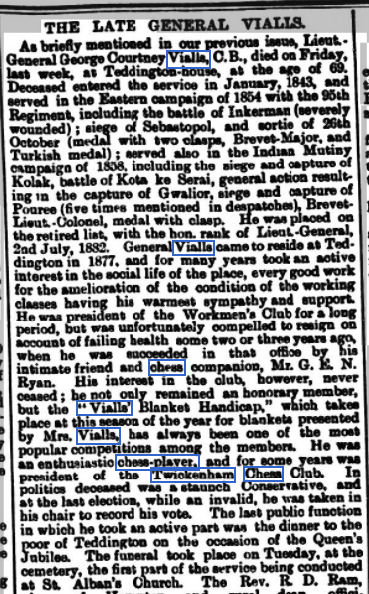

George Courtenay (Courtney in some records) Vialls is our man. He must have been pretty good at manoeuvring the toy soldiers of the chessboard as well as real soldiers in real life battles.

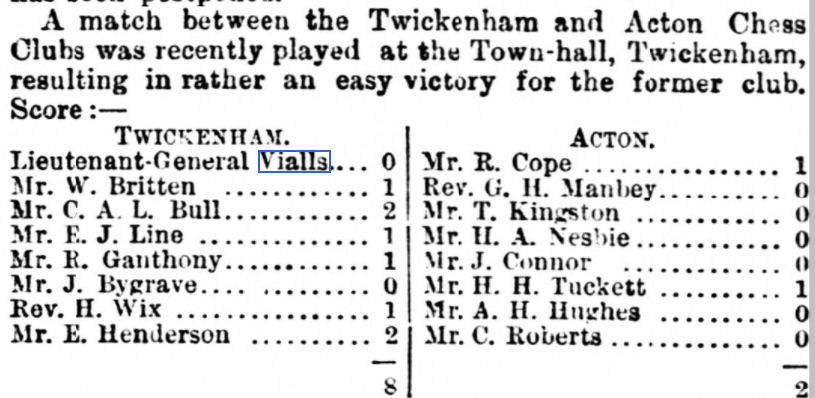

In this match he was on top board, ahead of the more than useful Wallace Britten, but this might, I suppose, have been due to seniority of rank rather than chess ability.

There are a couple of other interesting names in the Twickenham team here, to whom we’ll return in subsequent articles.

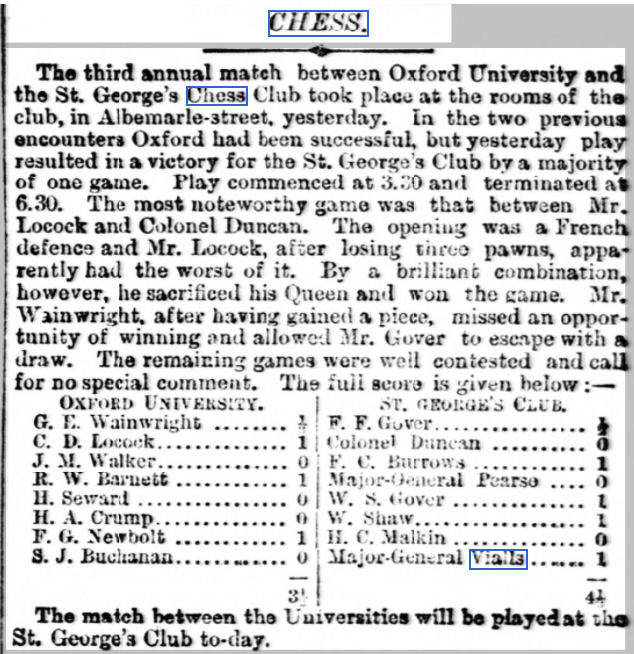

However, he was good enough to score a vital win for St George’s Club against Oxford University two years earlier.

You’ll note the two other high ranking army officers in the St George’s team, as well as two significant chess names on Oxford’s top boards (who may well be the subject of future Minor Pieces).

Vialls must have been a prominent member of St George’s Club as he was on the organising committee for the great London Tournament of 1883.

An obituary, from 1893, provides some useful information.

We learn that he was an intimate friend (no, not in that sense, but read on for some more intimate friends) of George Edward Norwood Ryan, and that he was a former President of Twickenham Chess Club.

Going back to the beginning, George Courtenay Vialls was the son of the Reverend Thomas Vialls, a wealthy and rather controversial clergyman. In 1822, prosecuted his gardener for stealing two slices of beef, which in fact his aunt had given him for lunch. He was himself up before the law two years later, accused of whipping his sister-in-law. Thomas had inherited Radnor House, by the river in Twickenham, from an uncle in 1812, and it was there, in 1824 that George was born.

He joined the army in 1843, serving in the 95th Regiment of Foot, and the 1851 census found him living in Portsmouth with his wife and infant daughter, awaiting his next assignment. That came in 1854 when his regiment embarked for Turkey and the Crimean War. At the Battle of Inkerman in November he was severely wounded and his commanding officer, Major John Champion, was killed in action. The regiment suffered further losses due to cold and disease. It was remarked that “there may be few of the 95th left but those few are as hard as nails”.

In 1856 they returned home, but were soon off again, at first to South Africa, but they were quickly rerouted to India to help suppress what was then called the Indian Mutiny, but we now prefer to call the Indian Rebellion.

Looking back from a 21st century perspective (as it happens I’ve just been reading this book), you’ll probably come to the conclusion that this was far from our country’s finest hour, but at the same time you might want to admire the courage of those on both sides of the conflict, and note that Vialls was five times mentioned in despatches.

In 1877 he seems to have been living briefly in Manchester, where he started his involvement in chess, taking part in club matches and losing a game to Blackburne in a blindfold simul.

The obituary above tells us that he moved to Teddington in 1877 (he was in Manchester in December that year so perhaps it was 1878), but the 1881 census found him and his wife staying with his wife’s sister’s family on a farm in Edenbridge, Kent. Perhaps they were just on holiday.

By 1891 they were in Teddington House, right in the town centre. It was roughly behind the bus stop where the office block is here, and if you spin round you’ll see the scaffolding surrounding Christchurch, in whose church hall Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club met for some time until a few years ago.

Before we move on, a coincidence for you. At about the same time the chess players of Northampton included a Thomas H Vials or Vialls, who was also the Secretary of Northamptonshire County Cricket Club, as well as a Walter E Britten, neither of whom appear to have been related to their Twickenham namesakes.

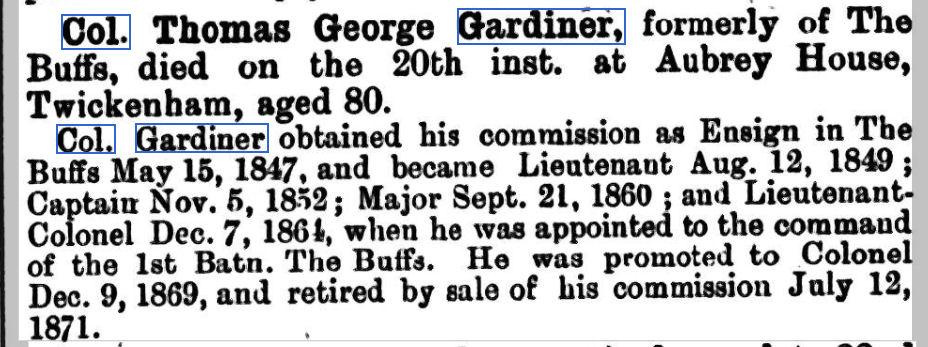

Our other military chesser from Twickenham, Colonel Thomas George Gardiner, was slightly less distinguished as both an army officer and a chess player, playing on a lower board in a few club matches in the early 1880s. As you’ll see, he came from an interesting family with some unexpected connection.

If you know Twickenham at all you’ll recognise this scene. The River Thames is behind you. Just out of shot on the left is Sion Row, where Sydney Meymott lived for a short time. On the right, just past Ferry Road, you can see the White Swan.

On the left of the photograph is Aubrey House, and the smaller house to its right with the pineapples on the gateposts is The Anchorage, also known in the past as Sion Terrace. As it happens I used to visit this house once a week in the mid 2000s to teach one of my private chess pupils.

The houses are discussed in this book, which I also referred you to in the Meymott post. At some point both Aubrey House and The Anchorage came into the possession of the Gardiner family: Thomas George Gardiner senior and his family were there in 1861 after he’d retired from work with the East India Company. The younger Thomas George had been born in Ham, just the other side of the river, in 1830 and chose an Army career, joining the Buffs (East Kent Regiment). He married in Richmond in 1857 and in 1861 was living in Twickenham with his wife and her mother’s family, described as a Major in the Army on half pay.

He apparently bought Savile House, out towards Twickenham Green, in 1870, but the family weren’t there in 1871. Perhaps he was serving abroad: his wife, ‘the wife of a colonel’, was still with her family, in Cross Deep Lodge, just a short walk from Twickenham Riverside. By 1881 he had retired, and the family were indeed living in Savile House. The building is long demolished: Savile Road marks the spot.

He sold the house in 1889, and the 1891 census unexpectedly found him in Streatham. Perhaps he joined one of the local chess clubs in the area. His wife died in 1896, and by 1901 he’d moved back to his father’s old residence, Aubrey House, along with a widowed daughter. He died in 1910: here’s his obituary from the Army & Navy Gazette.

The 1911 census records his daughter still in Aubrey House, along with three servants.

It’s worth taking a look at his mother, Mary Frances Grant (1803-1844), who was one of the Grants of Rothiemurchus, whose family, entirely coincidentally, are now the Earls of Dysart, the Tollemache family having died out. The Tollemache family owned Ham House until its acquisition by the National Trust in 1948, and a very short walk from Aubrey House will take you to Orleans Gardens, from where you can see Ham House across the river.

One of Mary’s brothers, William, married Sarah Elizabeth Siddons, whose grandmother was the celebrated actress Sarah Siddons. Another brother, John Peter Grant, married Henrietta Isabella Philippa Chichele Plowden. One of their daughters, Jane, married Richard Strachey: their famous offspring included the biographer and Bloomsbury Group member Lytton Strachey. One of their sons, the oddly named Bartle Grant, married Ethel Isabel McNeil. Their son was the artist and Bloomsbury Group member Duncan Grant. Duncan and his cousin Lytton had intimate friendships with very many people, including each other, and also including the economist John Maynard Keynes. His father, John Neville Keynes played chess for Cambridge against Oxford between 1873 and 1878, the last four times on top board. Strachey and Keynes also had relationships with WW1 and WW2 codebreaker Dilly Knox, who, until his death in 1943, worked closely with Alan Turing at Bletchley Park. His other colleagues there included leading chess players such as Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry.

So there you have it. George Courtenay Vialls and Thomas George Gardiner: two Twickenham men with distinguished military careers, both from very privileged and well-connected backgrounds. The Twickenham aristocracy, you might think, with their large riverside houses. Two men who, after decades commanding troops in real wars, spent their retirement commanding wooden soldiers on a chequered board.

We’re beginning to see a pattern within the membership of Twickenham Chess Club in the 1880s.

Who will we discover next? Join me soon for more Minor Pieces.

Sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

Google Maps

Twickenham Museum website