TF Lawrence (not to be confused with TE Lawrence, and certainly not with DH Lawrence) was one of that group of strong amateurs (about 2400 on retrospective ratings, so FM/IM strength by today’s standards) who were active in English chess in the years leading up to the First World War, all of whom are virtually forgotten today, and several of whom had connections with the area around Richmond, Twickenham, Kingston and Surbiton.

I’ve already featured two of their number, George Edward Wainwright and William Ward, here. Now it’s time to investigate the life and games of Thomas Francis Lawrence.

Let’s start by crossing the North Sea to visit a place very familiar to all chess fans: Wijk aan Zee. Before 1968 the tournament took place 5 km inland, in the city of Beverwijk. Immediately south of Beverwijk is the municipality of Velsen, divided by the North Sea Canal.

This canal was constructed between 1865 and 1876 to improve access from Amsterdam harbour to the North Sea. The chief engineer was John Hawkshaw and the contractors were Henry Lee & Sons of Westminster.

It was in Amsterdam, at some point between 1866 and 1870, that the marriage between Henry Lawrence and Esther Jane Izard was recorded. Our man Thomas Francis Lawrence was born in Velsen on 2 March 1871, and another son, Henry Arthur Edward Lawrence, followed on 8 August 1873.

Why were Henry and Esther in Velsen? Were they involved in the construction of the canal in some way? At the moment, I don’t know for certain. I can certainly identify Esther Jane Izard, who was born in Cheltenham in about 1834, although by 1841 her mother, Elizabeth, was a widow working as a laundress. I have no idea at all who Henry was, though: no one in his family seems to know and, as he had a fairly common name, there’s no way of finding out.

We can pick the family up in the 1881 census, living at 37 Henry Street, St Marylebone, which has been renamed Allitsen Road: you’ll find it in St John’s Wood, just north west of Regent’s Park. Esther, a widow, is working as a dressmaker, and her two sons, Thomas and ‘Edward’, are both scholars.

By 1891 they’ve moved to 32 Great George Street, which runs from St James’s Park to Big Ben and Westminster Bridge, with Downing Street just a stone’s throw away. Esther is now a housekeeper (which could mean all sorts of things) and her younger son, now named ‘Henry E A’, is a Solicitor’s Clerk. Thomas isn’t at home: I haven’t yet been able to locate him. It’s quite possible he was abroad at the time.

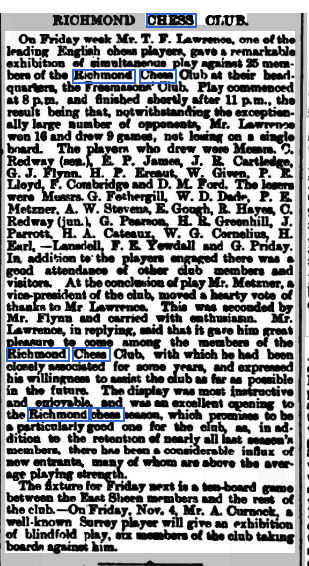

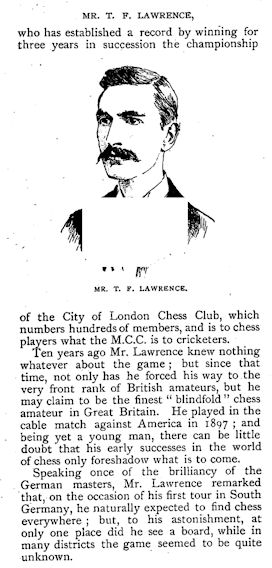

Thomas Francis Lawrence didn’t come from a chess playing background, and it was only round about this time that he learnt the moves. This didn’t prevent him becoming recognised, within only a few years, as one of the strongest players in London. His name first appeared in the press in 1893, playing for the City of London Club, and for the South of England against the North. He entered the City of London Club championship in 1893-94, sharing first place in his section, but losing the play-off against the eventual winner of the championship, Herbert Levi Jacobs. The following year he made the final pool, and in 1895-96 he won the Gastineau Cup for the first time. It wouldn’t be the last.

In 1895 he made the news playing a six-board blindfold simul match against Arthur Curnock (also mentioned in the above clipping), winning two games (scores available online) and drawing four.

This game was published in the Chess Player’s Chronicle on 16 October 1895, with White’s name being given as I Passmore and no venue. It’s reasonable to assume that the initial was incorrect and this was Devon born music teacher Samuel Passmore, and that the game might well have been played in the City of London CC Championship.

The fascinating Max Lange Attack was very popular at the time, and here White’s 23rd and 24th moves each cost half a point, as he’d missed Lawrence’s rather unusual winning coup. Click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up window.

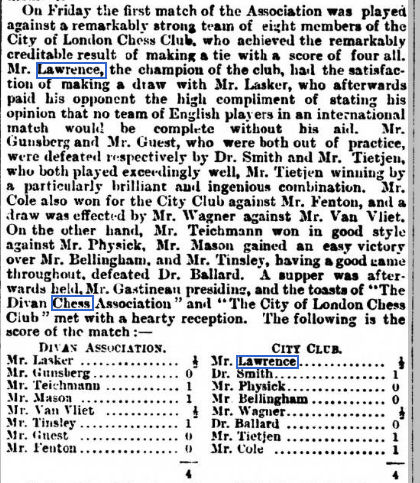

In 1896, playing on top board for the City of London Club against the Divan Chess Association, he found himself facing none other than the great Emanuel Lasker.

Here’s the game: you’ll see that Mr Lawrence totally outplayed his illustrious opponent, and was still winning according to Stockfish in the final position, where he was about to reach a queen ending with an extra pawn.

Perhaps Lasker had underestimated his opponent, but to go from learning the moves to outplaying the world champion in only a few years is a pretty impressive performance, I think you’ll agree.

Thomas won the City of London Championship again in 1896-97 and, for a third consecutive time, in 1897-98. At that time the winner received two trophies, the Gastineau Cup and the Mocatta Trophy, a full size Staunton ivory set and board, with silver mounts and inscriptions, valued at 16 guineas. The deal was that if you won the championship three times you got to keep the Mocatta Trophy in perpetuity, so the set and board was his.

In this game he demolished his opponent’s French Defence.

In this game from an inter-club match he took advantage of his opponent’s misplaced queen.

The City of London was not Lawrence’s only club. He was also representing Ibis, which tells us that, like Charles Redway, he was working for the Prudential Assurance Company.

Unsurprisingly, he soon came to the selectors’ attention, and in 1897 was chosen to play board 4 in the second Anglo-American Cable Match, where he lost to Boston lawyer John Finan Barry, miscalucating a tactical variation and losing a couple of pawns. He didn’t play the following year, but in 1899 again went down to the same player, being outplayed in a minor piece ending.

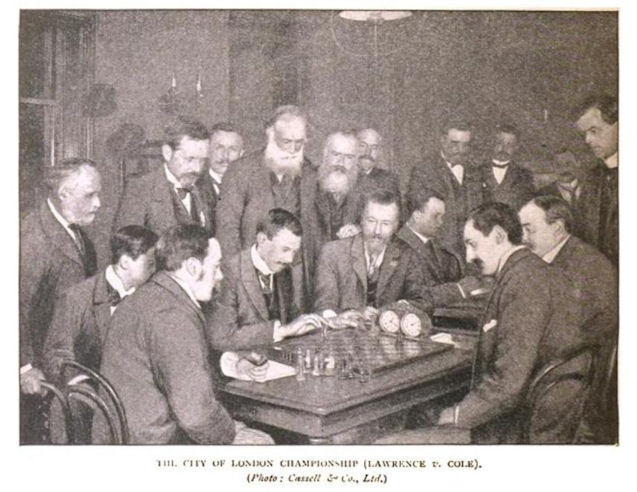

In 1898 Cassell’s Magazine ran a feature on amateur players at the City of London Chess Club, including this photograph of Thomas Francis Lawrence playing Henry Holwell Cole. (Thanks to Gerard Killoran for posting this on the English Chess Forum here.)

Here’s the accompanying pen-picture of Lawrence.

In 1899 he was invited to take part in a major international tournament that was due to take place in London. It was clear that he was considered a player of considerable potential who would benefit from crossing swords with the world’s finest. Even up to a couple of days before the first round it was hoped he would take part, but in the end he decided to reject the offer: I have yet to discover why. An even later withdrawal was Amos Burn, who stated that he was dissatisfied with the general arrangement of the tournament and with the supercilious treatment he received from some members of the management team.

In the 1898-99 edition of the City of London CC Championship Lawrence failed to retain his title: it was Herbert Levi Jacobs who had his name inscribed on the Gastineau Cup for the second time. One of the other players in the final pool was the novelist Louis Zangwill.

He was back on top in 1899-1900, though, with a score of 14½/17, a point ahead of William Ward, with the rest of the field well behind.

In April 1900 the City of London Chess Club ran an invitation tournament in which their leading members were pitted against leading foreign-born masters resident in London. Teichmann won with 9½/12, just ahead of Gunsberg and Mason, who shared second place, William Ward had an excellent result, just another half point behind. Lawrence finished on 50%, scoring 5/6 against the bottom half of the field, but only 1/6 against the top half. Not a bad result, and exactly as expected according to retrospective ratings, but neither did it suggest that he was ready to take on the world elite. In fact, looking at his games, you’ll have to admit he was lucky to score as many as he did: most of his wins came from opponents blundering in good positions. Here’s his best effort from this tournament, against Dutch organist Rudolf Loman.

A third cable match defeat, against Philadelphia building contractor Hermann Voigt, reinforced the suggestion that he was a strong amateur at this point in his career rather than a player of genuine master standard.

Lawrence’s style usually tended towards the safe and solid, but he clearly kept up to date with opening theory and favoured the sacrificial Albin-Chatard Attack against the French Defence. Here’s an example from the 1900-01 City of London Championship, against Canadian born doctor Stephen Smith, with a bonus game in the annotations. Alas, Smith and Jones indeed!

Lawrence was successful again in this event, getting his name on the trophy for the fifth time in six years. This time he notched up an impressive 19½/21, with Jacobs two points behind and Ward another point adrift.

By then it was time for the census enumerator to call round again. He found the Lawrence family still at 32 Great George Street, with not much changed from the past decade. Esther was still there, and still a housekeeper. Thomas and his brother, this time recorded as ‘Edward H A’, were both at home, and both working as clerks.

The association with Richmond isn’t obvious at this point: you’ll recall that in 1904 he claimed to have been associated with the club for some years, but in 1901 he was still in Westminster, although the District Railway would have taken him there reasonably quickly. He would have had friends there, from the City of London Club, and also Charles Redway from the Ibis Club.

What happened to Thomas Francis Lawrence next? Did he make the great leap forward to become a world class player? Did he continue his relationship with Richmond Chess Club? You’ll find out in my next Minor Piece.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

chessgames.com

MegaBase

The City of London Chess Club Championship (Roger Leslie Paige)

English Chess Forum

Chess Notes (Edward Winter)

BritBase

Gerard Killoran

Brian Denman

One thought on “Minor Pieces 41: Thomas Francis Lawrence Part 1”