Last time we left Alfred Lenton in 1939, at the outbreak of World War 2. Although Alfred didn’t serve in the war, there were fewer opportunities for him to play chess.

The county championship continued to take place, with Lenton retaining his title in 1940, and there was also a wartime county chess league, along with county matches against their Nottinghamshire neighbours.

In 1941 he was unexpectedly defeated by Philip Collier, who went to to claim his second county title, just as his father had done before him. In 1942 Elsie and Alfred welcomed their only son, Philip, into the world. (There were a lot of chess playing Phil(l)ips in Leicester at the time: Collier, Wallis, Rimmington and others.) He didn’t take part in the county championship that year, only resuming his chess career in 1945. In 1946 he was appointed President of the Leicestershire Chess Club, serving the required two year term.

He had intended to play in the 1946 British Championships in Nottingham, but had to pull out at fairly short notice: whether due to work or family commitments is unclear. But he was still playing successfully in the county championship, claiming his fifth and sixth titles in 1947 and 1948.

In June 1947 a Czechoslovakian team visited England to play two matches, against an England team in London, followed by an encounter with a Midlands team in Birmingham. Alfred resumed his international career here where he was matched against Jaromir Florian (not the Hungarian Tibor as incorrectly given in MegaBase and other sources). Thanks to Christopher Kreuzer and others on the English Chess Forum for researching and confirming this.

Two interesting games ensued, with our hero scoring a win and a draw. Click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up window.

By August that year he felt ready to commit himself to the British Championships, held that year in Harrogate.

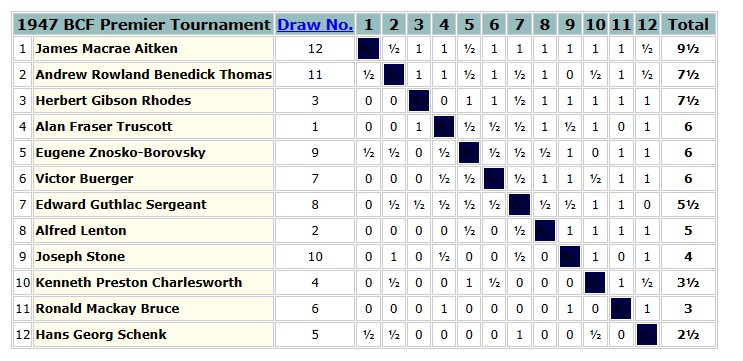

He was selected to play in what was called the Premier Tournament, the section immediately below the championship itself, also a strong competition with some international interest. Lenton, not for the first time, started slowly, but recovered to finish on 5/11.

Tournament report and further details here.

Here are two of his wins.

You’ll see that, by this time, although still throwing in the occasional hypermodern opening from pre-war days, he was usually playing in much more classical fashion.

Every year around this time he’d give a simultaneous display against fellow members of the NALGO (Local Government Officers) Chess Club. Here he is pictured in 1949, alongside the big news of a pigeon being arrested in Coalville. Strange things often happen in Leicestershire.

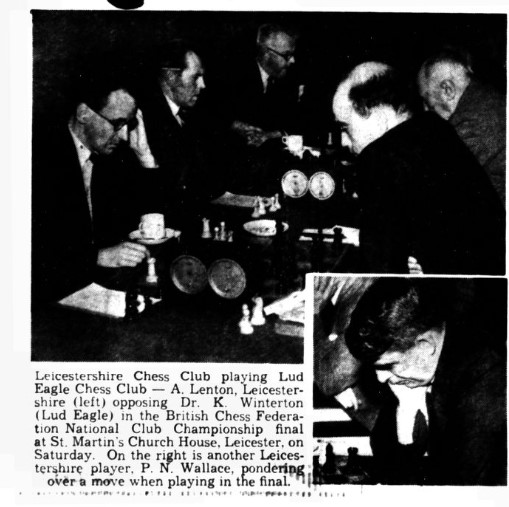

In 1951 Leicestershire Chess Club reached the final of the National Club Championship, going down 4-2 against the London club Lud-Eagle. Alfred drew his game on board 4, pictured here.

In 1954 Lenton won the county championship again, playing enough chess to make the BCF Grading List in Category 3a (209-216) which you can see here, although he dropped out the following year.

Round about this time he decided on a change of career, giving up his job in local government to establish an antiquarian bookshop in the city centre, which, at various times sold all sorts of other things: model railways, stamps, gramophone records for example. This enterprise afforded him less time for chess, especially county matches as Saturday was his busiest day.

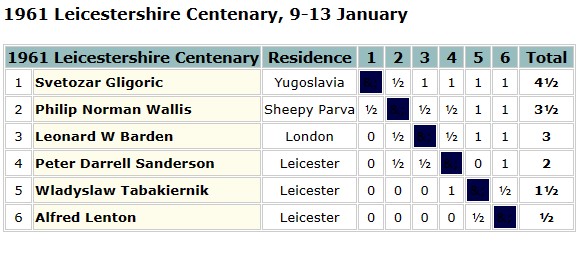

In 1960, as you may recall, the Leicestershire Chess Club celebrated its centenary. As part of the celebrations a tournament was organised in January the following year.

They invited one of the world’s strongest players, Svetozar Gligoric, and one of the country’s strongest players, Leonard Barden, both of whom had just competed at Hastings, to take on the four most recent county champions.

As well as Alfred Lenton, champion in 1954, they were Polish player Wladyslaw Tabakiernik (1915-1997, known as Tabby, champion in 1952 and 1953), Philip Norman Wallis (1906-1973, champion in 1955, 1956, 1958 and 1959), and Peter Darrell Sanderson (1934-2013, champion in 1957 and 1960).

Here’s the final table.

Tournament report here.

Tournament report here.

It soon became clear that Alfred was very rusty. Young star Sanderson beat him with a fine combination in the first round.

In Round 2, Wallis, playing black, had a winning attack by move 14. In Round 3, against Barden, he was again lost by move 14, losing two pawns to an obvious tactic.

Against the great Gligoric he started well enough, but a tactical oversight led, after a series of exchanges, to a position where his opponent could play a temporary knight sacrifice to end up two pawns ahead. Disheartened, he resigned rather than waiting to be shown.

In his final game he gained a clear advantage against Tabakiernik, but decided to play safe by offering a draw.

He was in better form in this county match game played a couple of months later against one of England’s most promising young players.

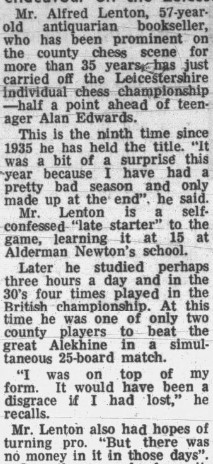

Leicester 1961 was to be his last major tournament, but Alfred continued playing locally with success. He was interviewed by the local paper following his triumph in the 1969 county championship.

Sadly we have very few games available from the last 40(!) years of his chess career. Here’s a game he lost against an opponent he’d beaten on top board of a county match two years earlier.

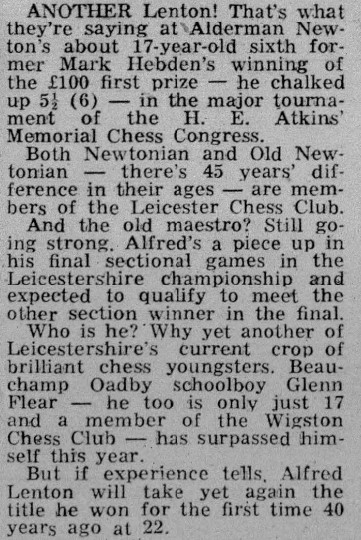

In the 1970s, buoyed by a strong local organisation, Leicester was at the forefront of the English Chess Explosion, with several teenage stars coming to the fore. Here, a young Mark Hebden, a pupil, as Lenton had been many years earlier, at Alderman Newton’s School, was being compared to Alfred.

There, you’ll see another future GM, Glenn Flear, a pupil at Beauchamp Oadby School, which had originally been Kibworth Grammar School in the village from which the Lentons came. Elsewhere, Flear’s ‘smooth positional style’ was compared to that of Lenton. Other contemporaries were future IM Geoff Lawton, Shaun Finlayson and Alan Richardson.

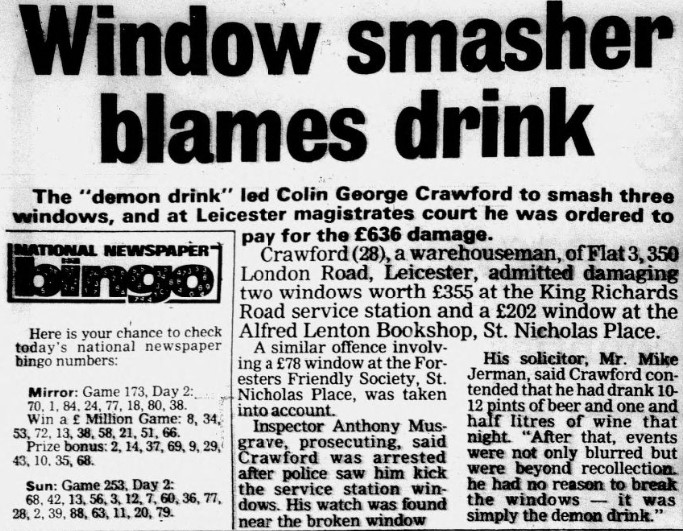

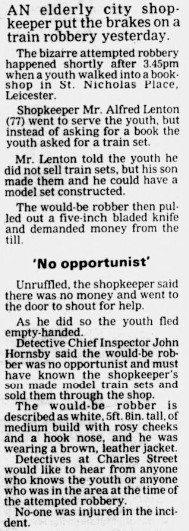

The 1980s seems to have been a quiet decade for Alfred Lenton as a chess player, but life in his shop was, on occasion, rather more eventful.

In 1988 he made the front page of the papers for foiling a train robbery.

Later in life he became active again, playing for his local club, Thurnby: we have a draw from a match between Thurnby 2 and Market Harborough.

Jonathan Calder blogged about this game here: many thanks to him for looking out the scoresheet for me. There’s another story concerning an informal game played in his shop here.

Shabir Okhai has sent me a game he played against Lenton in 1999, when he was 14 years old. You’ll see Alfred, just as he had done, more than 60 years earlier, chose a hypermodern opening, and, after missing some winning chances, exceeded the time limit in a position which offered chances to both sides.

Alfred Lenton (always Alf to his friends) died on 5 November 2004 at the age of 93. You’ll see from the ECF ratings site that he was active almost to the end. I guess not many players who had previously been about 2300 strength eventually plummeted to about 1600, but then not many of them continued playing into their tenth decade. The game above suggests that he had problems with time management at the end of his long career.

I met Alfred a couple of times myself, at Sandys Dickinson’s second hand bookshop in London, while looking for material for The Complete Chess Addict, but don’t have any particularly strong memories of him. I wasn’t certain then that the P Lenton I’d played in Leicester was his son, and had no idea of our family connection.

The shop is still there, or at least is was last time Google Maps passed by. I presume Philip still runs it.

Here it is, dwarfed by a hairdressers and a branch of Subway on either side. You can see a photograph (is that Philip behind the counter?) here.

There you have the long life of Alfred Lenton, a life devoted to chess, as an international player, as a journalist, and as a lover of chess books. Perhaps an unconventional life, but, I’d say, a life worth lived.

While I still have your attention, I’d like to introduce, very briefly, another long lived Leicester player.

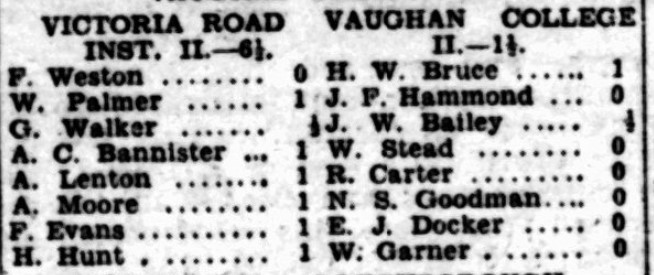

Here’s one of Alfred’s earliest games, and there, on the board above him, is our man, Arthur Clement Bannister.

Arthur, born on 18 February 1891, was twenty years older than Alfred, but the two men would have known each other well for half a century.

If Alfred was a Minor Piece in chess, Arthur was a mere pawn, but pawns, according to Philidor, are the soul of chess. You’ll meet men like Arthur in almost any chess club. An average, or perhaps below average club player who turns out regularly, plays on a low board in county matches and takes in the occasional tournament (Bannister played in the Short 3rd Class section at Margate in 1938 and the 2nd Class Section A in the 1952 British Championships).

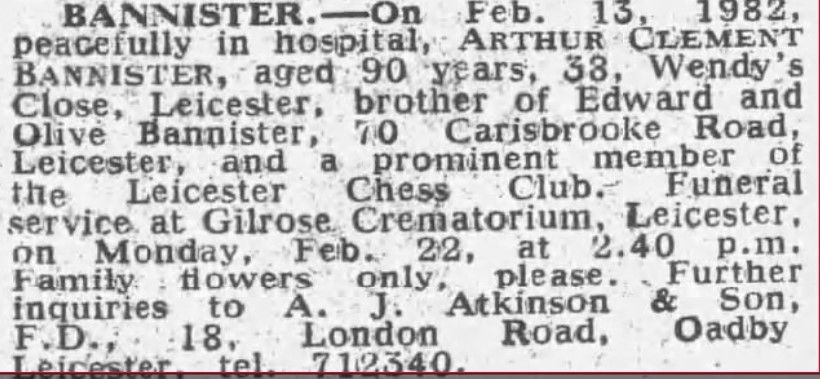

You’ll see from his death notice, that, even at the age of 90, he was ‘a prominent member of the Leicester Chess Club’. I’d put it to you that it’s the likes of Arthur Clement Bannister who are the real soul of chess.

Arthur, who never married, had a hearing impairment, which might, perhaps, be two reasons why chess meant so much to him. In a 1950 match against Coventry he was paired against a blind player, but the captains agreed that they should swap opponents with the adjacent board.

Arthur’s father, James, was born in the town of Earl Shilton, ten miles to the west of Leicester. I wrote more about his family – and their connection to my family – here.

So, back there on adjacent boards in 1929, and friends for half a century or more, were my mother’s kinsman Arthur and my father’s kinsman Alfred, both of whom lived into their nineties. I can see something of myself in both of them. Not so much a golden chain: perhaps a golden helix.

One final thought, though. I’d put it to you that one reason why so many strong young players came from Leicester in the 1970s was the strength of their club and county chess scene. There was a thriving local league, featuring formidable players like Alfred Lenton as well as enthusiasts like Arthur Clement Bannister. There were organisers of many years’ experience, and journalists such as Don Gould and Dick Chapman who tirelessly promoted the game in local newspapers over several decades. You might meet more of them in future Minor Pieces, but for now it’s time to take the train back to St Pancras and return to London.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

BritBase (John Saunders)

John Saunders also for providing me with his Lenton file

ChessBase/Stockfish 16

English Chess Forum/Christopher Kreuzer and others

chessgames.com

chess.com

EdoChess (Rod Edwards)

Google Maps

Chess in Leicester 1860-1960 (Don Gould)

Jonathan Calder

Shabir Okhai