Last time we visited the Yorkshire seaside resort of Scarborough in the company of Francis Joseph Lee, just a few weeks before his untimely death.

Congresses like the British Championships only take place if there’s someone there to organise them, and, as it happened the prime mover of this one was someone who was mentioned in a different context just a few Minor Pieces ago.

Lowestoft Journal 04 September 1909

Lowestoft Journal 04 September 1909

Didn’t Edward Wallis do well? He had a long involvement with the game of chess, and this, along with the publication of his book of miniature problems, was one of his life’s highlights. You might recall that one of George Law Francis Beetholme‘s problems was included therein.

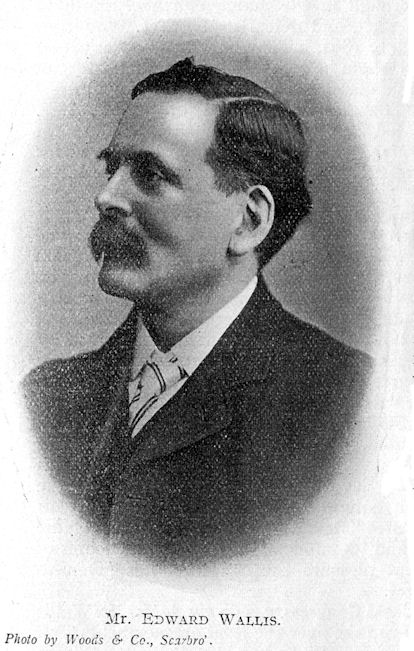

Here he is, pictured in the September 1909 British Chess Magazine.

Edward Wallis had an interesting story to tell, one that involves, as well as chess, chocolate and conscientious objection.

Let’s go back to the middle of the 17th century, when, in the aftermath of the English Civil War, a new religious group founded by George Fox, known as the Society of Friends, or the Quakers, became popular. Jumping forward a century or so, a Quaker named Joseph Fry started a business producing drinking chocolate in Bristol. In 1831 another Quaker, John Cadbury, started producing drinking chocolate in Birmingham. In 1862, Henry Isaac Rowntree, also a member of the Society of Friends, bought out the chocolate making part of the Tuke family’s York business. These three companies, Fry, Cadbury and Rowntree, would become the three major producers of confectionery in Britain through the remainder of the 19th and much of the 20th century.

The Rowntrees had been a prominent Quaker family in Scarborough for a very long time. and, by the early 19th century, John Rowntree was running a grocery business there. His son Joseph moved to York to start a grocers shop in 1822, and it was his son Henry Isaac who started the confectionery business. Joseph’s brother William remained in Scarborough, and it was his grandson, Alderman John Watson Rowntree, who was the chairman of the committee running the 1909 British Championships in his home town.

The Wallis family were also prominent Quakers, from the village of Springfield in Essex, now a suburb of Chelmsford. After his marriage in 1849, Francis Wallis moved from Essex to Scarborough, no doubt in part because of the strong Quaker presence there, setting up as a corn dealer and miller. One of Francis’s daughters, Priscilla Gray Wallis, married George Rowntree, a brother of the aforementioned John Watson. One of Francis’s sons, born in 1852, was Edward Wallis, author of 777 Chess Miniatures in Three (you can read it online here) and the local organiser of the 1909 British Chess Championships.

In 1877 Edward married Dublin born Annie Johnson in London, returning to Scarborough, and, at some point in the 1880s, moving to a house they named Springfield after his home village. Their children were Eleanor (1878), Edward Arnold (1880), Arthur (1881), Dorothea (1883) and Annie Mabel (1885). He ran a grocery and bakery business there for the rest of his life.

On 24 January 1880 Edward had a chess problem published in the Leeds Mercury Weekly Supplement. At 27 years of age he was a relatively late starter in chess.

Problem 1: Mate in 3: you’ll find the solution at the end of this article.

In the same year he was also seen playing correspondence chess. In this game from a Leeds Mercury tournament he had the better of the opening but rather lost the plot thereafter.

In this game, probably played in the same event, he defeated schoolteacher GW Farrow, born in Scarborough, but by that time living in Hull

In 1881 he entered a correspondence tournament run by the Preston Guardian. This win against GW Farrow was almost certainly (although this isn’t specificed in the source) played in the 1881 edition of the Leeds Mercury competition.

In 1882 he won an exciting, but not entirely sound, game against Scarborough Chess Club secretary and chemist Henry Chapman.

In January 1883 he played on Board 53 in a match between Lancashire and Yorkshire, losing his game against Dr Dean of Burnley. The Manchester Courier (27 January), with an element of hyperbole, claimed that this was “the greatest chess match which has ever taken place in the history of the royal game, which extends over a period of more than 3,000 years”.

Here’s a game he lost in another correspondence tournament run by the Leeds Mercury. After White’s alert response to his erroneous 22nd move he could only choose which bishop to lose. (Click on any move of any game in this article for a pop-up window.)

He also lost this game, played in a correspondence game between two players representing clubs at almost opposite ends of the country, misplaying a tricky ending. It’s not clear whether or not this was a formal match between the two clubs.

In 1891 Scarborough were treated to a visit by our good friend Francis Joseph Lee.

An excellent result for Edward: it would have been good if they’d published the game. Mr F Wallis was probably Edward’s father Francis, but we’ll come to another possibility later.

Later in the same year he was one of the protagonists in a living chess game raising money for a good cause.

During this period, Edward Wallis was playing on top board for Scarborough, but, to be honest, there wasn’t that much opposition. Most of the county’s stronger players resided in the larger towns and cities.

In January 1893 he was selected to represent the North of England against the South in a 100 board megamatch in Birmingham, but ended up not in the match itself but on the bottom reserve board where he won his game against Wiltshire’s CJ Woodrow.

In April Scarborough welcomed another professional visitor: Samuel Tinsley. This time Wallis was less successful.

“… in a game known as the Queen’s Fianchetto?” I think the journalist was rather confused.

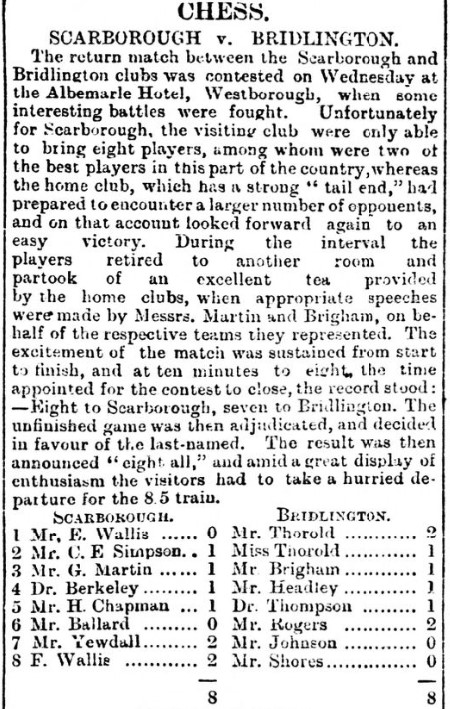

Here’s a report on a 1894 match against Bridlington, the days when matches were interrupted half way through for an excellent tea and appropriate speeches.

You’ll see that (presumably) Edward’s father won both his games on bottom board. The Mr Yewdall on Board 7 was the teenage Francis Edward Yewdall, who, almost 40 years later, would become the Secretary of Richmond & Kew Chess Club (where he was the assistant borough surveyor), and therefore, if you want to stretch a point, one of my Great Predecessors. Charles Empson Simpson, on Board 2, was Edward’s next door neighbour. You might notice some name connections: Wallis and Simpson living in adjacent houses, and Wallis (but not Simpson) living in Springfield. Bridlington, very unusually for the time, fielded a lady on second board: Eliza Mary Thorold, sister of their top board Edmund, who had been for many years one of the country’s top amateurs but was now approaching the end of his career.

Here’s one of the top board games, in which both sides missed chances.

A few weeks later there was another North v South megamatch, over 108 boards. Edward Wallis was on Board 102, losing to Horace Fabian Cheshire, who would soon find fame as the editor of the Hastings 1895 tournament book.

By 1897 he’d ceded top board to Charles Empson Simpson, and in 1899 he played on Board 9 for the North and East Ridings of Yorkshire in a match against the West Riding, losing his game against Isaac McIntyre Brown, the editor of the British Chess Magazine. Simpson lost on fourth board to John Musgrove.

One thing that you may know about the Quakers is that they are noted for their liberal views, many of their members being committed pacifists, and that was certainly true of the extended Rowntree family in Scarborough.

Appalled by the atrocities of the Second Boer War, a South African Conciliation Committee was set up in Scarborough under the presidency of Joshua Rowntree, a cousin of Henry Isaac and a former Liberal MP for the town. In March 1900 a meeting was arranged. One of the speakers was Samuel Cronwright, British born but living in South Africa and married to author and anti-war campaigner Olive Schreiner, still remembered today for her 1883 novel The Story of an African Farm. The other speaker, John A Hobson, was a prominent anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist.

There were some in Scarborough who considered their views heretical and unpatriotic. Word got round about the meeting, and a crowd, brandishing Union Jacks, formed outside, smashing the windows and throwing stones. Not content with that, some of them proceeded to vandalise the shops and houses of other members of the Rowntree family.

Perhaps you were, like me, unaware of this story, which, of course, has many resonances today. If you’d like to read more there’s a paper on the riots here.

If you’re interested in the history of the Rowntree family I’d recommend visiting the Rowntree Society website. This page is a good place to start.

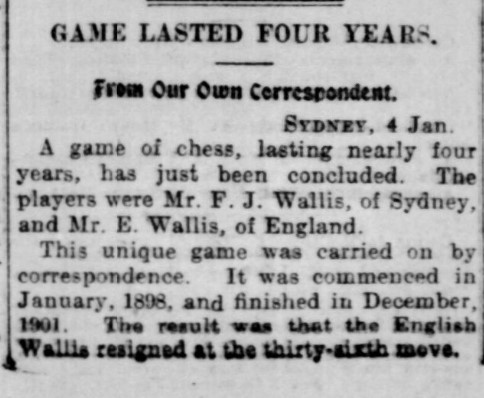

While all this was going on, it appears that Edward Wallis was engaged in a long-range postal game.

I’m pretty sure, although it’s not mentioned in the press, that FJ Wallis was Edward’s brother Francis John Wallis, and that he had emigrated to Australia in 1891, becoming prominent in Sydney chess circles. In that case the F Wallis mentioned twice above would definitely be Edward’s father Francis senior.

A few years later, this game was published in the British Chess Magazine with, typically for the time, rather inaccurate annotations by Bellingham. The loser, at lease in my secondary source, is incorrectly identified as AG Wallis.

By now Scarborough Chess Club seems to have become inactive, putting Edward Wallis’s chess career on hold. His name started to reappear towards the end of 1907, when he made two contributions to a testimonial for FR Gittins, the author of The Chess Bouquet, which was being organised by the always witty Philip Hamilton Williams. He also announced that he was collecting miniature (no more than 7 pieces on the board) mates in 3. In 1908 he published a self-mate in 16 based on an earlier problem by Frederick Baird, but it turned out to be unsound as there were quicker solutions.

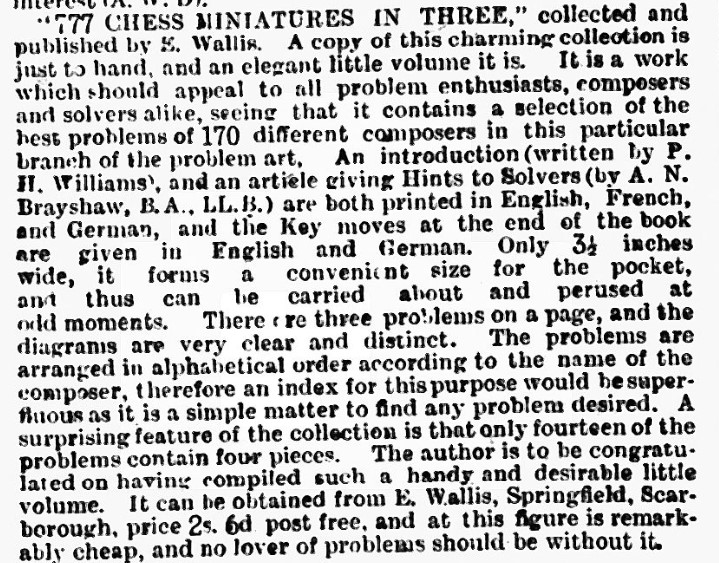

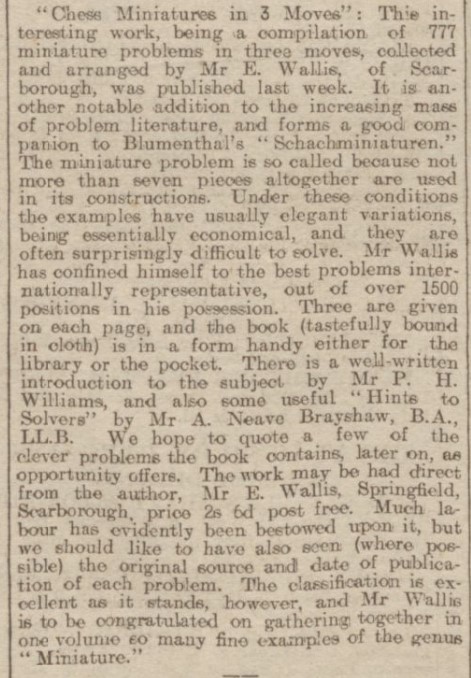

By October 1908 his book was (self-)published, receiving positive reviews.

Then, in 1909, came the second highlight of his life: the British Chess Championships in his home town, which you read about earlier. Although he was referred to as being from Scarborough Chess Club, I haven’t found any other mentions of the club between the late 1890s and the 1920s.

In 1910 he had a problem published in The Chess Amateur. It’s a mate in 3, but not a miniature.

Problem 2: #3 (E Wallis The Chess Amateur 1910)

Now, it seems, having perhaps fulfilled his two ambitions, he cut down his chess activities, confining himself to solving problems in newspaper columns.

When the First World War broke out his family commitment to pacifism was tested again. The older of his sons, Edward Arnold (below), registered as a conscientious objector, serving in the Friends Ambulance Corps between 1915 and 1918.

His younger son, Arthur, on the other hand, joined the RAF in 1918, but as a lecturer rather than in a combat role.

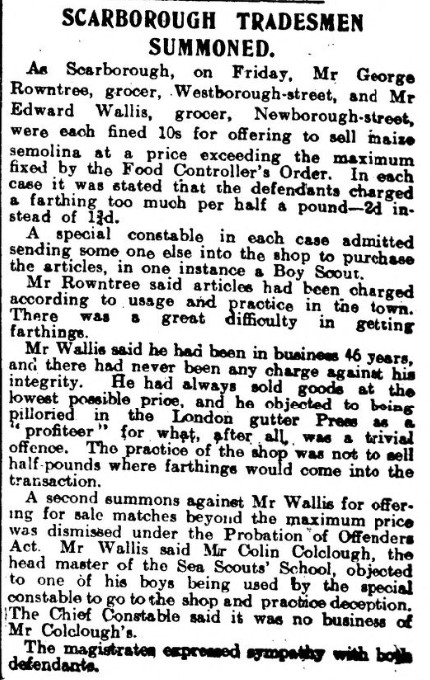

In 1917 George Rowntree and Edward Wallis unexpectedly fell foul of the law for selling semolina above the maximum fixed price.

In 1921, the census tells us that Edward was still running the family business at the age of 69, living with his wife and youngest daughter, who was working as a hospital nurse.

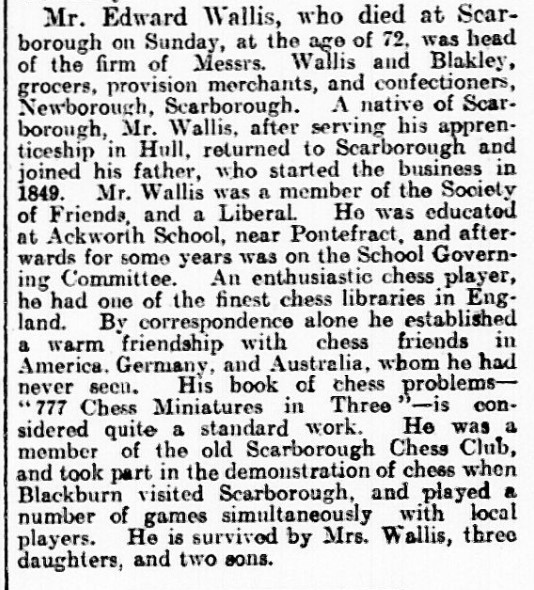

He died a year later, this newspaper obituary erroneously adding two years to his age.

Edward Wallis wasn’t, by the highest standards, a very strong player, nor was he a great problemist. But, as well as taking part in competitions, both over the board and by post, and occasionally composing problems, he was a true chess enthusiast, an author, an organiser and a collector, with one of the finest chess libraries in England (I wonder what happened to it). He was also a man who, along with his extended family and friends, lived his life through the principles expounded by the liberal Quakers: pacifism, integrity and service to the community. A life, I think, that deserves to be remembered, and a story that deserves to be told.

Next time, I’ll continue the story by introducing you to his friend who kindly contributed the Hints to Solvers to his book: Alfred Neave Brayshaw. Be sure not to miss it.

Sources and Acknowledgements

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Digital Chess Problems (Anders Thulin) website (Wallis book here)

Wikipedia

MESON Chess Problem Database (Brian Stephenson)

BritBase (John Saunders: thanks for the photo)

Yorkshire Chess History (Steve Mann): Edward Wallis here

Gerard Killoran for the Bays, Farrow and Chapman games.

David McAlister for reconstructing the Bays game (on the English Chess Forum)

Rowntree Society website

Guise Family website (George Rowntree here)

The Men Who Said No (Peace Pledge Union website: Edward Arnold Wallis here)

Solutions to problems:

Problem 1:

1. Qf6! is the key, threatening Nc7+, Qd6+ and Qxd4+. There are short mates in reply to either queen capture. You can see the full solution here.

Problem 2:

1. Qh2! (threat: Qe2#) 1… Kc4 (1… Ke4 2. Qe2+ Kf4 3. Be5#) (1… Bxc3 2. Qe2+ Kxd4 3. Ne6#) 2. Qa2+ Kb5 (2… Nb3 3. Qa6#) (2… Kd3 3. Qe2#) 3. Nc7#