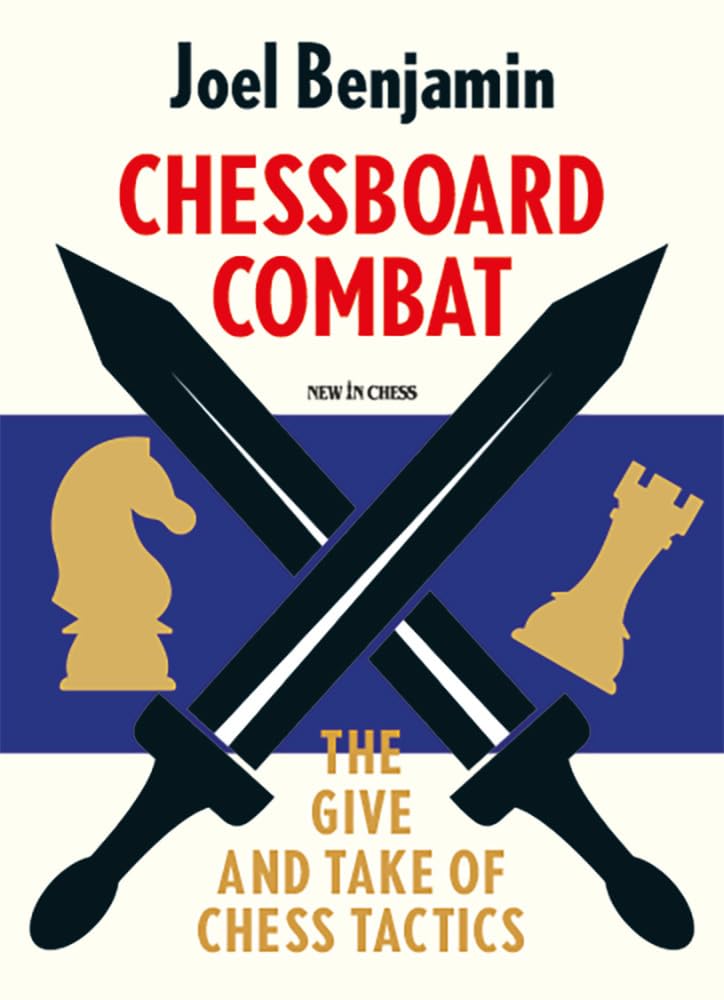

From the back cover:

“Chess students love a Puzzle Rush. And solving tactics puzzles certainly helps you improve your pattern recognition and will help you find good moves in tournament games. But there is a downside to most tactics puzzles — we always know who is supposed to win!

Chess in real life is different, not just because no one taps us on the shoulder and tells us to look for a tactic. Sometimes tactics work, and sometimes they don’t. Sometimes your opponent has a few tricks up their sleeve, too.

This book shows the reality of chess tactics. It explores a chess player’s challenges over the board: attack, defense, and counterattack! It exposes the actual give-and-take nature of chess tactics.

American grandmaster Joel Benjamin, a three-time U.S. Champion, was inspired by the 20th-century classic Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by legendary chess authors Fred Reinfeld and Israel Albert Horowitz. With modern examples, Benjamin arouses the same spirit of fun and enjoyment. With a generous amount of puzzles in quiz form, this manual will help chess students sharpen their tactical skills and be ready to strike – or counterstrike.”

About the Author:

“Joel Benjamin won the US Championship three times and has been a trainer for almost three decades. His book Liquidation on the Chess Board won the Best Book Award of the Chess Journalists of America (CJA), and his most recent book Better Thinking, Better Chess is a world-wide bestseller.”

I’ve recently been reviewing books on endgames and grinding, and understandably so as well.

Here’s something, as they say, completely different.

I’ve always liked the Tal quote: “You must take your opponent into a deep dark forest where 2+2=5, and the path leading out is only wide enough for one.”.

That’s what we get here. 129 thrilling games in which the tactics could go either way. The author’s main source was his ‘Game of the Week’ series which ran for several years on ICC, so if you followed that you’ll have seen some of the games before. You may well enjoy meeting them again, though. While there are a few familiar chestnuts, many of the games are likely to be new to most readers.

Chapter 1 is Strike, Counterstrike, ‘the fundamental give-and-take nature of chess tactics’.

Chapter 2 tells us that The King is a Fighting Piece, and bears some similarities to the Steel Kings chapter of one of my all-time favourite chess books, Tim Krabbé’s Chess Curiosities.

Take this position, from Spassky – Polugaevsky (USSR Championship 1961).

White could have mated by marching his king further up the board, to f7, but instead played Kh5. This should have led to a draw, but he later blundered and lost.

Here’s the complete game. Click on any move for a pop-up window.

Chapter 3, Dodging Defenses, is much shorter, looking at how the attacker with a plethora of tempting continuations might choose the one that negates the opponent’s attempt to escape.

Chapter 4, Staying Alive, is more David Smerdon than John Travolta. Here, we look at how to maximise our chances of a successful defence, perhaps by looking for swindles.

Here’s a position from a game in which an amateur threw all his pieces at his 500 point higher rated GM opponent.

It proved effective, as Black erred with 29… Qc8, after which White demonstrated the win, as you’ll see below. The winning move would have been 29… Nxd4, but these things are never so easy over the board, even against a massively lower rated player.

Chapter 5 is another short one: Trying Too Hard to Win. In a complex position you sometimes have to decide whether to take a draw (for instance by repetition) or try for more. If you’re too ambitious it might well backfire.

It can work the other way as well.

In this position England’s new No. 1 Vitiugov missed a snap mate against Svidler, taking a perpetual with 26… Nf3+?, when he might have preferred 26… Qa5+! 27. b4 Qxb5!! 28. Qxb5 Nc2+ 29. Ke2 f3#.

The complete game again:

Chapter 6 looks at Back Rank Tactics, which might be the key to a winning combination, or provide an unexpected defence. All players at all levels should be familiar with these ideas.

Chapter 7, In the Beginning … and in the End, considers two very different topics. First, we’re shown a couple of openings which often lead to tactical mayhem: the King’s Indian Defence and the Marshall Attack in the Ruy Lopez. Engines now consider the former close to unplayable and the latter more or less a forced draw, but at anything below GM level they’re worth playing – and often a lot of fun. Then we look briefly at some endgame tactics.

Finally, or almost finally, Chapter 8, Whoops!, looks, as you might expect, at blunders, in particular the nature of mistakes and the misconceptions that cause them.

The book concludes with Chapter 9, Tactical Tips, 30 useful suggestions to help you improve your tactical play.

The first eight chapters open with some puzzles based on the games in that chapter: a total of 78 in all, to provide interactive content for those who wish to avail themselves.

The examples throughout have been expertly chosen, although I suppose another author might have chosen different chapter headings or placed some of them in different chapters. In a book of this nature there will be considerable overlap. The annotations are excellent: Benjamin does a first class job in getting the balance right between computer and human assessments, which, in complex positions can be very different from each other. I’m pleased that the complete games are always given, rather than just the tactics at the end.

The production is well up to this publisher’s customary high standards, although, as everyone does, they fail the Yates test (he was Fred, not Frederick).

You might not consider this an essential purchase, but, if you like games of this nature, and who doesn’t?, you’ll enjoy and perhaps learn from this book. It’s certainly enormous fun for all lovers of red-blooded tactical chess. The names of the author and publisher are guarantees of excellence, and I’d consider it suitable for everyone of average club standard or above.

If you’d like to see more before deciding whether it’s for you, you can read some sample pages here.

Book Details:

- Softcover: 224 pages

- Publisher: New In Chess (5 April 2023)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9493257835

- ISBN-13:978-9493257832

- Product Dimensions: 17.22 x 1.42 x 23.01 cm

Official web site of New in Chess.