I recently introduced you to the competitors in the first London Boys Chess Championship, which took place in 1923-24.

Let’s look at how the competition progressed over the next few years.

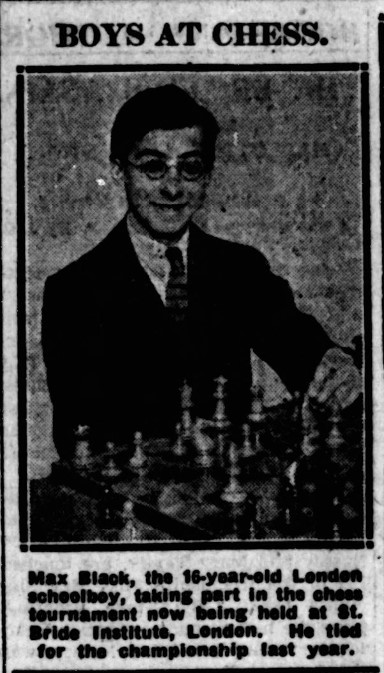

In 1924-25 there were again ten competitors. Five had returned from the previous year: Black, Bowers, Brüning, Excell and Smith.

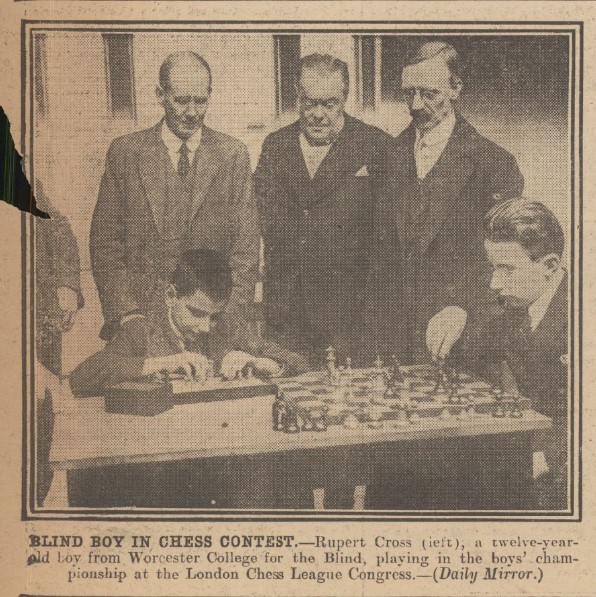

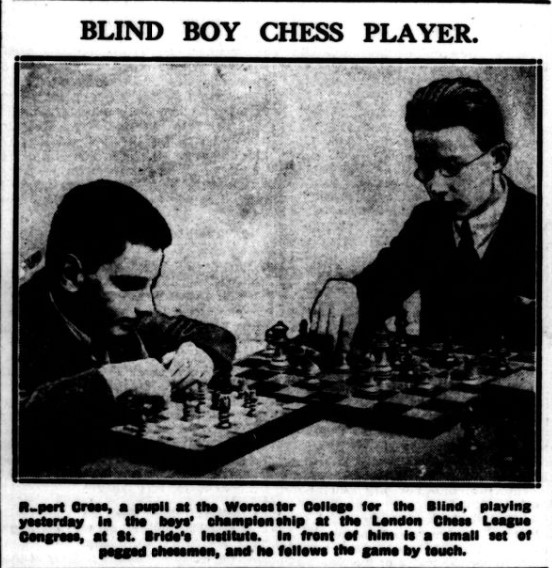

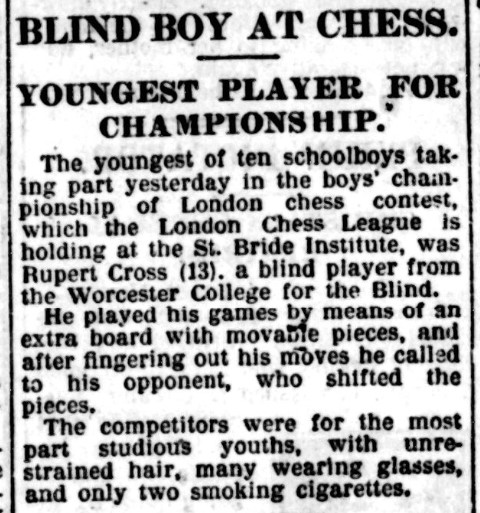

One of the newcomers in particular attracted a lot of press attention. This was the young blind player Alfred Rupert Neale Cross (1912-1980), known as Rupert, a pupil at Worcester College for the Blind.

He wasn’t new to competitive chess, having taken part in the British Boys Championship the previous April when he was only 11. But the press, intrigued by the novelty, provided short paragraphs about how he played the game. He was also photographed, as here in the Daily Mirror…

… and also in the Daily News.

Linlithgowshire Gazette 09 January 1925

Linlithgowshire Gazette 09 January 1925

The Staffordshire Advertiser (10 January 1925) published this game between the two youngest players, commenting that it is a really excellent game when considering that Rupert Cross is a blind boy, and has to play with board and pieces specially made for the blind.

Click on any move for a pop-up window.

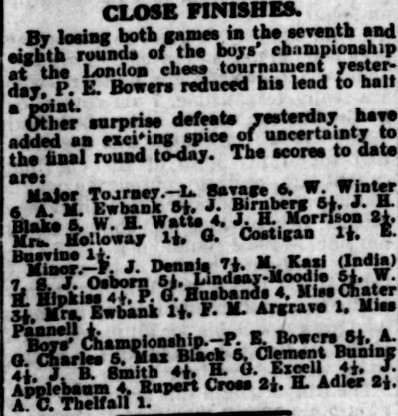

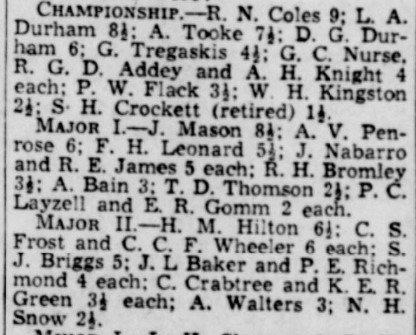

The last record I have of the complete scores was this, from before the final round.

The Daily News didn’t publish the full final results, but we know that Bowers, Black and Charles all finished on 6/9 (or perhaps 6½/9: sources differ), with Excell and Smith on 5½/9, and that Cross finished on 3/9.

It was therefore the established players who, for the most part, dominated. The only interloper was Alfred George Charles, one of two competitors who would live to witness the 21st century (1907-2001). Alfred was the son of an insurance agent (previously a letter sorter), born in Holloway, North London, but, by the 1921 census, living in Tooting. He was educated first at Seddon Street School in Canonbury, and then at Battersea County (Polytechnic Secondary) School. He had previously taken part in the 1924 British Boys Championship, where he performed fairly well. In 1933 he married a South African girl who later worked as a physiotherapist: they had three daughters, one of whom died in infancy. By 1939 he was working for the Statistical Office of the Ministry of Supply in Rugby, which must have been temporary war work as the family had settled in New Malden.

Did Alfred go on to have a glittering chess career? Sadly not: this seems to have been his second and last appearance in competitive chess.

Rupert Cross wasn’t the only pupil of Worcester College for the Blind taking part in the tournament. There was also Arthur Charles Threlfall, who, as he wasn’t mentioned in the press reports, was probably partially sighted and didn’t require a special board. Arthur who was another who had a long life (1910-2002), was a Worcester pupil from 1921 to 1928. His family came from Clapham, and his father seems to have had a variety of jobs, including working as an agent in metals and for a paper. By 1939 he was an area manager for an electrical goods company in Solihull before moving to Salisbury.

Threlfall continued playing chess while he was in Worcester, sometimes representing his county on one of the lower boards.

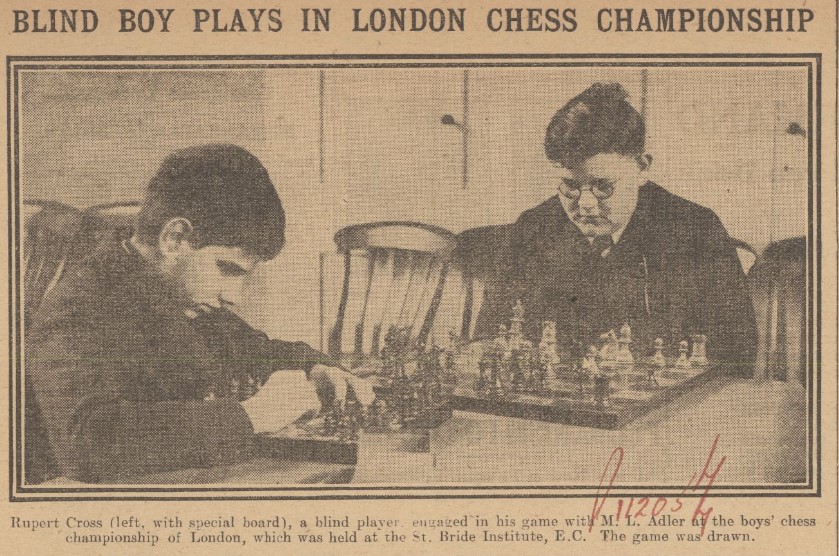

The other two competitors were both, like Black, Jewish. Moses Lazarus Adler (1908-1978) was living in Whitechapel in 1921, just round the corner from where Mary Ann Nichols had been murdered by Jack the Ripper on 31 August 1888. His father, a newsagent, was Polish and his mother Russian. He married in 1932, but in 1939 was still living with his father, by now a widower, and the rest of his family, working as the secretary of a skin merchants’ company. Towards the end of his life he seems to have moved to Canada, where his brother had earlier emigrated.

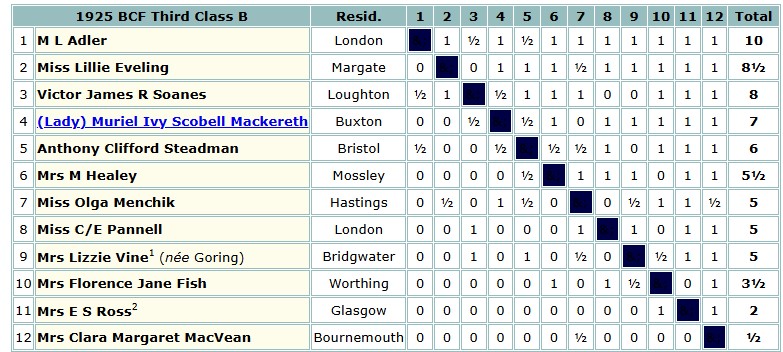

Moses had made his tournament début in the British Championships at Stratford on Avon the previous summer, in the 3rd Class B section.

You’ll see he scored a convincing victory against a field including future BCF President Vic Soanes and Vera Menchik’s sister. You’ll also note with interest that nine of the 12 players in this section were female.

He returned to the London Boys Championship the following year, and continued playing occasionally in Middlesex through the 1930s, appearing in county matches and winning the Minor section of the 1937 county championship.

The most interesting competitor, apart from Cross, in the tournament was the player whose surname was variously given as Apfelbaum, Appelbaum and Applebaum. There were several possible candidates named John/Jack in birth and census records but I eventually managed to locate him through an obituary.

Our John, born in 1908, came from a Polish family: his father, born in Łódź, was from a family of merchants, but, in 1921, living in Greek Street, Soho, was employed more humbly as a tailor’s cutter, a job he still had in 1939.

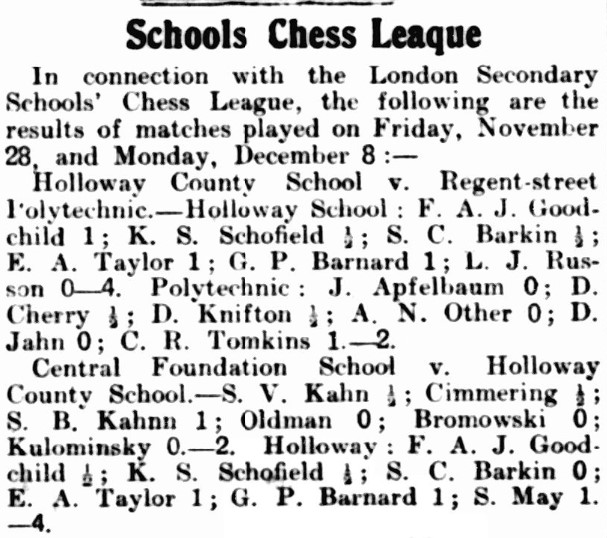

Here he is in a school match and there, in the other match reported in the same column, is a certain Bromowski, who was actually the great polymath and chess player Jacob Bronowski.

The family later changed their name to Apley, and it’s under that name that we can pick up the rest of John’s life. In 1927 he won a scholarship to study medicine at University College London. On completing his studies he became a GP in Pinner, and was also developing an interest in paediatrics. On the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserves as a medical specialist based in Wiltshire, rising to the rank of Squadron Leader. After the war he worked in paediatrics in Bath and Bristol, but with a few spells abroad, becoming, as well as a much loved doctor, a prominent author, teacher, lecturer and broadcaster. His obituary on the website of the Royal College of Physicians tells us that he was also a musician, playing oboe and clarinet, a first class chess player, a golfer and skier

You can see him on YouTube giving a tour of the Bristol Children’s Hospital.

His obituary is here and find details of his books here.

The following year there were again ten competitors. I’d assume there may have been more applications but the selectors chose the players they considered to have the best credentials.

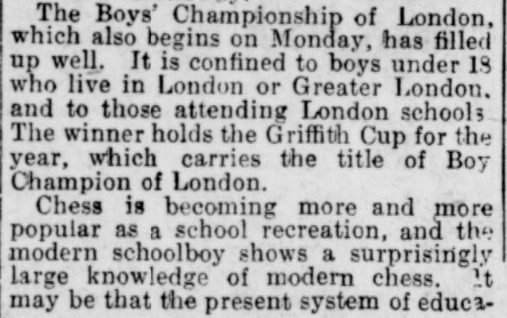

The event still had something of a novelty value. The Evening News told its readers about the growing popularity of chess in schools.

Evening News (London) 02 January 1926

Evening News (London) 02 January 1926

Rupert Cross was back again, as explained by the Daily News, who were not averse to repeating some still current stereotypes.

Here’s Rupert again, playing Moses Adler.

And here’s a smiling Max Black.

I don’t have the names of all ten participants at present but I can identify (at least) six returnees along with (at least) three newcomers.

As in the previous year there was a three-way tie for first place on 6/9, with two of the players repeating their earlier success: Black, Bowers and Smith.

Two of the newcomers shared 4th place on 5½: Geoffrey Harold Rowson and Simon Edward Bloom Solomons.

Geoffrey is of considerable interest. He was born on 14 May 1910, the younger of two brothers, Leslie having been born in 1905. His birth was registered in Brentford, so he might, like me, have been born in West Middlesex Hospital. His family name was originally Rosenbaum, so he may have prononced the first syllable of his surname to rhyme with ‘know’ rather than ‘now’. His mother was Esther Bloomer Caro: I haven’t been able to find any immediate connection with Horatio. Geoffrey’s father, Simon, founded a film distribution company along with his brother Harry in 1911. Ideal Film Company were originally distributors but soon started producing their own films.

Harry, who was himself a chess player, moved on to other things, spending time in America where, at one point, he worked with Emanual Lasker. Simon was later joined by his older son, Leslie, who himself became a renowned cinematographer.

Geoffrey was educated at St Paul’s School in West London, which would later count the likes of Jon Speelman, Julian Hodgson and William Watson amongst its pupils. He spent a few years, 1926 to 1928, playing chess, taking part in the London Boys Championship on three occasions and the British Boys Championship twice.

In the 1926 British Boys Championship he lost this game to a young C H O’D Alexander, that year’s winner.

Moving briefly forward, the following year Geoffrey became British Boys Champion, but after the 1928 London Boys Championship he moved on to other things in his life. After working for the family company for a short time he decided to branch out, becoming an accountant working for Marks & Spencer.

The 1939 Register found Geoffrey, his wife and their young son Henry living in a leafy suburb of Nottingham. He then moved to Leicester, where he returned to the chessboard, playing in the county wartime league and in informal matches against Nottinghamshire.

At the same time he also joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve, qualifying as a pilot of Avro Lancaster bombers.

On the evening of 17 January 1943, his plane took off from Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire, but never returned. It appears that it was shot down by a German night fighter, crashing into the sea off the Dutch coast. You’ll find more details here.

In a tragic coincidence, the following year, John Henry Hewitt, the son of the man who donated an equipment cupboard to Twickenham Chess Club, and whose story was told in my previous Minor Piece, would lose his life in exactly the same way.

Geoffrey and John were both members of the RAFVR, both flying Lancasters, and both losing their lives when their planes were hit by night fighters.

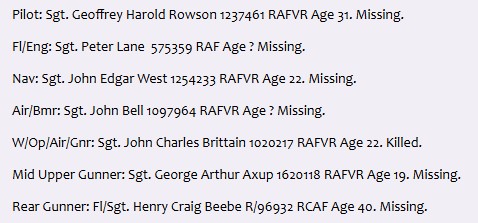

Here are the names of Geoffrey’s crew. We should never forget the brave young men who paid the ultimate penalty in our fight against Fascism.

Unfortunately I haven’t been able to find a photograph of Geoffrey, but here’s his brother Leslie as a young man.

Sharing 4th place with Rowson was Simon Edward Bloom Solomons. Simon was born in Battersea on 2 May 1908, but by 1911 the family had moved to Willesden, where his father ran a tailor’s shop. His business was sufficiently successful for him to afford to employ a servant. The family were still there in 1921, but, as Simon was educated at Owen’s School, they may have moved to Islington at some point. They would return to Willesden later.

This seems to have been his only foray into competitive chess. On leaving Owen’s School, Simon went to London University, where he was awarded a General BSc.

He married Ada Eisman in 1936 (pictured below) but, to the best of my knowledge they had no children.

The family moved around quite a lot. In 1939 they were in Wycombe, where Simon’s occupation was given as a Civil Servant and Physicist. In the late 1940s and early 1950s Simon and Ada were living in Ruvigny Mansions, a block of mansion flats on Putney Embankment, where they were near neighbours of Enid Mary Lanspeary, They must have retired to Chichester, where Simon’s death was recorded on 25 January 1996.

The other new name in 1926 was one with some very local connections to me: William Francis Darke.

William was born on 8 December 1911 in Twickenham. For some reason he was baptised in Eastleigh, Hampshire, although neither of his parents had any obvious connection there, with his address given as 4 Gothic Road, off Staines Road not far from Twickenham Green, and his father’s occupation given as a farmer. The 1911 census, though, found the young and newly married Francis and Ada Darke at 95 Staines Road, Francis was born in the Devon village of Lamerton: his occupation here was given as a railway engine stoker working for the South Western Railway. Make of it what you will.

We can pick up the family again in the 1921 census, where the family’s address was 40 The Green, Twickenham. (This address is now a house down an alleyway behind Sainsburys, but the numbering might have changed since then.) Francis had been promoted to an Engine Driver with the London and South Western Railway, while young William had been joined by siblings Leslie and Alma.

William, a bright boy, gained a place at Hampton Grammar School, where chess was popular at the time (and indeed still is, although these days it’s just Hampton School). He learnt the moves from a children’s encyclopaedia.

His first tournament was the 1926 British Boys Championship, where he won this entertaining but inaccurate game. His opponent, the son of missionaries and born in what was then Madras, would go on to win the London Boys Championship in 1928. I also recall him playing for Staines in the 1970s and 1980s.

However, he lost a piece in the opening against (Arthur) Eric Smith: 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 a6 4. Ba4 Nf6 5. O-O b5 6. Bb3 Nxe4 7. d4 f6 8. dxe5 d6 9. Bd5 and White eventually won.

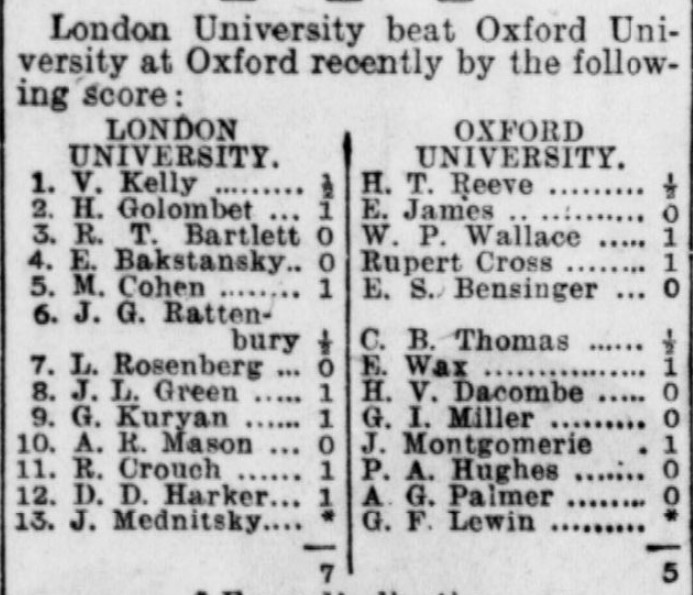

William played in both the British and London Boys Championships for several years, reaching the final stages of the former in 1928, and drawing with Harry Golombek, who went on to win the title, in the London 1929 event.

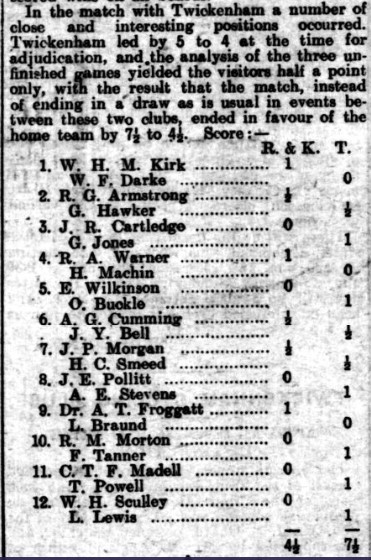

He also joined Twickenham Chess Club, in this match against Richmond & Kew, playing on top board against Wilfred Kirk.

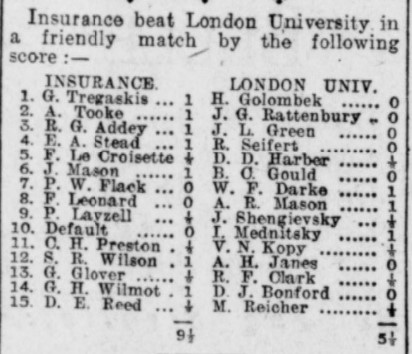

On leaving Hampton Grammar, William continued his studies – and his chess at London University. In this match Harry Golombek was unexpectedly beaten by George Tregaskis on top board.

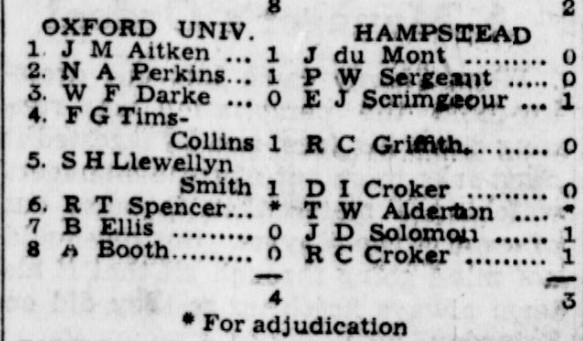

From London University he then joined Balliol College Oxford, playing for the University team, but not selected for the Varsity matches.

(In a further tragic coincidence, FG Tims Collins would also, like Geoffrey Rowson and John Hewitt, lose his life in a Lancaster bomber: details here.)

On leaving Balliol, William joined the Civil Service, working as an economist in agriculture. His job soon took him to California, where he met and fell in love with a GP’s daughter named Marjorie Aileen van Vorhis (or Vorhies: sources vary).

Here she is now, from the University of California Berkeley 1936 Yearbook.

After what must have been a whirlwind romance, they wasted little time tying the knot: they were married before the year was out, settling in a newly built house in Beech Way, a short walk from Twickenham Green in one direction and from where I currently live in the other direction.

But something very quickly went wrong. By the time of the 1939 Register, just a few months later, he was back at home with his family, claiming to be a widower.

Except that he wasn’t. The 1940 US Census found Marjorie back at home in California with her mother, working as a schoolteacher.

They briefly reunited: in 1947 they were living in 12 Arlington Park Mansions, Chiswick, a block of mansion flats overlooking Turnham Green. At number 9, just down the corridor, was the eminent novelist and chess enthusiast EM Forster (commemorated by a blue plaque on the wall). One wonders if William and Morgan ever got together for a few games. But by 1948 they’d split up again, with William having returned to his family in Twickenham.

By 1955 he was living on his own in Grange Avenue, just the other side of Twickenham Green, and, curiously, registered as a Service Voter, implying that he was in the Armed Forces, although that indication had disappeared by 1957. He was still there in 1961, but had moved on by 1962, to where I don’t know.

The only other information I have is that William Francis Darke died in Eastbourne, a popular retirement destination, on 13 November 1998. It seems that he and Marjorie had reunited again: she also died in Eastbourne, on 30 April 2006. One online tree suggests they had a daughter, but I have no more information. She may have been born and brought up in California.

I’ll conclude for now by taking a look at the 1927 event.

Rupert Cross was still attracting press attention, but he was not the only prodigy taking part.

The Daily Chronicle managed to get a lot wrong. Rupert had, of course, competed for the London Championship before, and it also seems rather odd to describe Capablanca as imaginative rather than scientific. The sub-editor writing the headline seems to have made the mistaken assumption that this was a knock-out competition.

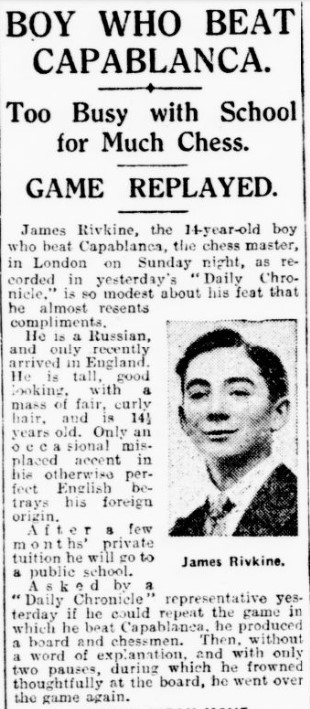

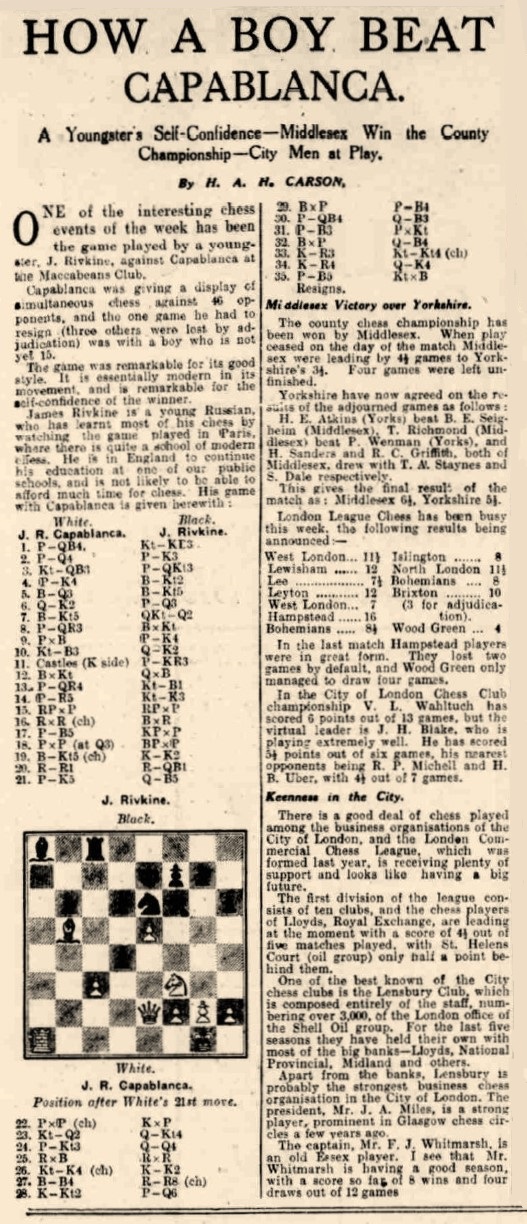

We need to go back just over a year to witness James Walter Rivkine’s success against the great Capa.

London Daily Chronicle 15 December 1925

London Daily Chronicle 15 December 1925

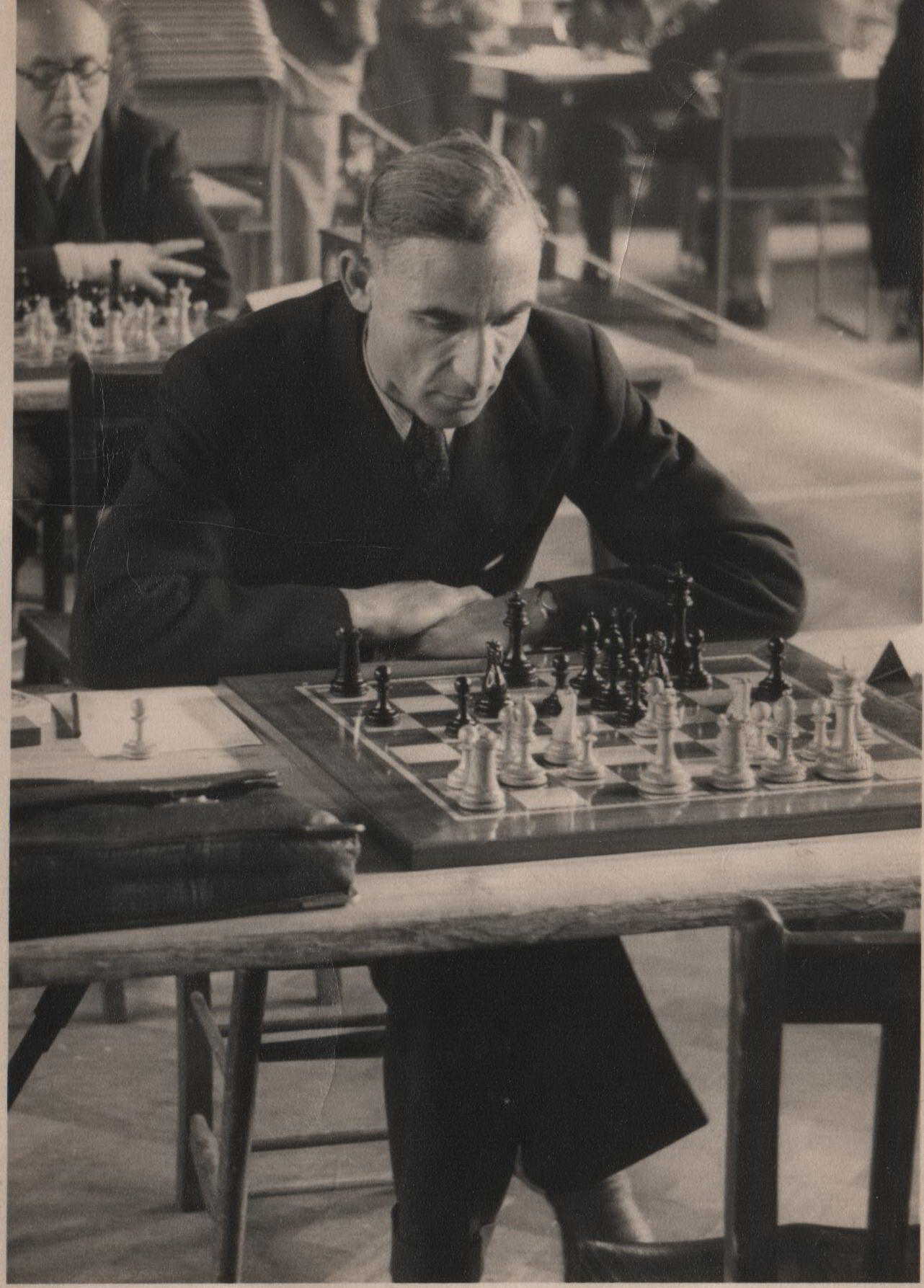

He doesn’t look from the photograph as if he has a mass of fair, curly hair, does he?

The Evening News published the game.

Even Stockfish was impressed with Rivkine’s play.

The tournament this year had a different format. This time there were 16 entrants, split into two all-play-all groups of eight, with a final pool to determine the top four placings.

James had rather more difficulty with his opposition here than he did against the World Champion, failing to finish in the first three places in his group.

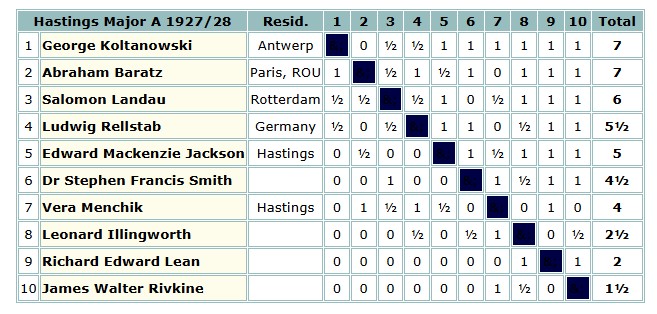

The following year he gave the London Boys Championship a miss, playing at Hastings instead.

The selectors, giving more credence to his win against Capablanca than his less than stellar results against his contemporaries, placed him in the Major A section, in itself a pretty strong international event: the two winners were, according to EdoChess, above 2400 strength.

Although he was somewhat outclassed, he did have the satisfaction of winning an excellent attacking game against Vera Menchik.

His loss against Landau was also entertaining.

We can see from these games that Rivkine was a creative attacking player with excellent tactical skills, who, with more experience, might well have reached master standard. But, as he suggested in the above interview, he decided to focus on his studies instead.

He was also interested in chess problems, in August 1928 winning a prize in a newspaper solving competition, his address being given as 58 Priory Road Kew Gardens, just the other side of the railway line from the National Archives. By 1931 he was in Hampshire, where he played for the county: playing on Board 3 against Devon he beat Harold Mallison, and, also on Board 3 in 1932, losing to Edward Guthlac Sergeant of Middlesex. On 5 May 1933 he was awarded a Certificate of Naturalization, making him a British citizen. His name was given as Isaac Ritvine, known as James, and he was described as a commercial traveller from Southsea. In 1936 he married Irma Willk, a dental student, and in 1939 was back in London, in Heathfield Court, Chiswick, working as a gas engineer. This is another block of flats alongside Turnham Green, just round the corner from where William Francis Darke would briefly live. James (or Jimmie as he was known within the family) and Irma didn’t stay there very long either: after the war we find them in Cricklewood, North London. After Irma’s death in 1990 he retired to Bournemouth, where he died in his late 90s in 2008.

His memory lives on today. His grandson Simon runs a business consultancy, JWR Ventures, named after his beloved grandfather’s initials.

Simon writes about him here.

James Walter Rivkine did not know when he was born – his UK passport said 1911, his birth certificate stated 1910 and when you asked him he had no real idea! He knows he was born an only child in St Petersburg, Russia and when he was about 10 years old was brought to stay with family friends in Paris by his mother – his parents feeling the real threat of the pogroms closing in. Promising to return with his father, his parents tragically did not make it back to Paris (killed in the pogroms) so James found himself orphaned and alone in pre-war Paris.

However, tragedy seemed to follow wherever life took him, with his wife and both of his children dying before he finally peacefully slipped away aged 97 (we think :-)) in his apartment with a view over the majestic Bournemouth beach on the south coast of England. He was a man that lived a thousand lives, spoke six languages and charmed hundreds that came into contact with him. Sure he had times when he was depressed, pained by all the emotional and physical challenges that life threw at him but he somehow picked himself up and got back on the saddle again more times than I care to remember.

Winding the clock back more than 80 years, I don’t have the names of all the competitors in the 1927 London Boys Championship, and I haven’t been able to identify some of the names I do have.

There were a lot of new entrants, and, unlike previous years, it was they who were the most successful.

The winner was Vincent Peter Kelly (1910-1954), the son of a police officer from Carlow, Ireland, and a pupil at St Ignatius College. This was his first tournament, and would be his only first place, although he would share second place the following year. Vincent was a problemist as well as a player, and, during 1927 had a number of problems published mostly in the Catholic newspaper The Tablet.

Here are a couple of them.

In this mate in 2 (The Tablet 09-04-1927), the key move leaves Black in zugzwang.

Another mate in 2 (mistakenly first published as a mate in 3: The Tablet 27-08-1927), a battle between the black queen and the white bishop.

The solution to the first problem is Qf3, and to the second problem is Ne8. You can work out the variations for yourself.

On leaving school he proceeded to London University, where he played for them in friendly matches, on occasion, as here, on top board ahead of none other than Harry Golombek.

On graduating he became a maths teacher in Essex, but then joined the RAF as a pilot in the Meteorological Branch, later transferring to the Admin and Special Duties Branch, and finally to the Education Branch, eventually reaching, like John Apley, the rank of Squadron Leader.

He had married in 1937, but the marriage soon broke up, his wife obtaining a divorce on the grounds of his desertion. He remarried in 1949, but sadly died young in 1954.

In second place was Harold Israel (1909-1984), the son of an elementary school teacher from Willesden, another Owen’s School pupil.

Whereas many of his contemporaries stopped playing once life, in the shape of work and marriage, got in the way, Harold was someone who continued playing chess at a high level for many years. One reason for this was perhaps that he never married. He was working in the textile industry at the time of the 1939 Register.

For several decades he was one of London’s strongest amateur players, the highlights of his career were sharing the British Correspondence Championship with Frank Parr in 1948-49 and sharing 2nd place in the 1952 British Championship. In the first BCF Grading List, published in early 1954, he was graded 2b (217-224, or about 2350 today).

There’s a discussion about him from some years ago on the English Chess Forum here. This photograph comes from an online family tree.

These two games from different stages of his career bear witness to his tactical ability.

In third place was yet another newcomer, Douglas George Durham (1911-1993). Douglas’s father was a tailor from Tottenham, North London. His older brother, Leonard Ambrose Durham (1904-1996), also a chess player, was, at the time of the 1921 census, working for what was then Crawley, Dixon & Bowring, Insurance Brokers: they later became simply Bowrings.

Here are the family, again in 1921, at their sister Queenie’s ill-starred wedding.

Douglas is on the left on his father’s lap, and Leonard is the young man in the bow tie standing behind the bridesmaid.

He took part in the London Boys Championship in 1928 and 1929 as well, without equalling this performance. By 1930 he was working for Bowrings alongside his brother, where they were seen taking the top two boards for their company team in the Insurance League.

In 1931 Leonard tied with our old friend George Tregaskis in the Insurance Championship, with Douglas down the field sharing 8th place.

In the 1934 Insurance Championship Douglas lost this game against Nevil Coles, who would later write several excellent chess books.

The top sections of the 1936 Insurance Championship included three of my opponents from more than half a century ago: Nevil Coles, Godfrey Nurse and Rodney James (no relation: he had been a competitor in the first British Boys Championship).

Both brothers were later involved in chess in Hertfordshire, where Leonard lost this Best Game Prize winning game to a Scottish international and, later, author.

The two Durham brothers continued playing for a time after the war, but it seems like they gradually withdrew from chess in the early 1950s. They were both strong amateur players, though: I suppose Leonard would be about 2100 and Douglas about 2000 in today’s money.

Fourth place was occupied by Geoffrey Rowson, while the 5th and 6th places were shared between Max Black, unable to repeat his successes of the previous two years, and Rupert Cross. James Rivkine was further down the field, along with William Darke.

There’s one other story I want to share briefly: when you see the name Barnett Bodgin you really have to investigate further.

Barnett, born 15 February 1909 (according to the 1939 Register), lived in Mile End, in what was then the Jewish quarter of London. His family had only just arrived there when he was born: his older siblings, along with his parents, were born in Vitebsk, in what is now Belarus. In the 1921 census, his father, Israel, was working as a Boot Upper Maker. There’s something odd here: The census clearly states he was aged 13 years and 10 months (which, I think, would have made him too old for the tournament), but, if the date of his birth registration and his 1939 claim is to be trusted, he was 12 years and 4 months. Who knows?

Other sources give his name as Barnet Bogin and sometimes also Slobodin: he later changed it to Lawrence Byron. By 1939 he was married to his first wife and living in Manchester, working as an engineer for a radio company. He died in Sale, Cheshire, in 1966.

This seems to have been his only experience of competitive chess.

Here he is with what I’m reliably informed is a Renault, probably a Town Car.

With Lawrence and his car, it’s time to conclude, at least for the moment, the stories of the boys who took part in the London Boys Chess Championships a century or so ago.

What can we learn from this?

Two things immediately stand out from looking at the demographics of the young players.

Firstly, you’ll note that the Jewish community were strongly represented, ranging from the sons of long established families such as Simon Solomons to new arrivals like James Rivkine. We can see this mirrored today: many of the leading young players, and this is true across all English speaking countries, come from the South and East Asian communities.

This was also a time of considerable social mobility, a time of a rapidly growing middle class, and a time when the concept of hobbies for children of secondary school age was starting to take off.

We can see here bright boys from lower middle or working class backgrounds who were winning scholarships to grammar schools, and sometimes then continuing their studies at London University. There was now a schools chess league in London: if you were fortunate enough to attend a school where one of the masters was interested in chess, a club would be set up, matches would be played against other schools, and you’d be encouraged to take part in competitions such as this. I note that my old school, Latymer Upper, wasn’t playing chess at this time, but its local rival, St Paul’s, and my local grammar school, Hampton Grammar, were both strongly represented in boys’ chess tournaments in the inter-war years.

While many of them dropped out of competitive chess on completing their education, there were some who remained hobby players for the rest of their lives, while, for Harry Golombek, chess became a career. But all of them would have retained their love of the world’s greatest game.

And what, you may well ask, about the girls? That will be another article for another time, but I have some other stories to tell first.

Join me again soon for some more Minor Pieces.

Sources and Acknowledgements

ancestry.co.uk (various family trees)

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archives

PapersPast

Wikipedia

YouTube

BritBase (John Saunders)

English Chess Forum

British Chess News

chessgames.com

EdoChess (Rod Edwards)

ChessBase 18/Stockfish 17

MESON chess problem database (Brian Stephenson)

Yet Another Chess Problem Database (YACPD)

Royal College of Physicians website

aircrewremembered.com

JWR Ventures website

Various other sources mentioned above