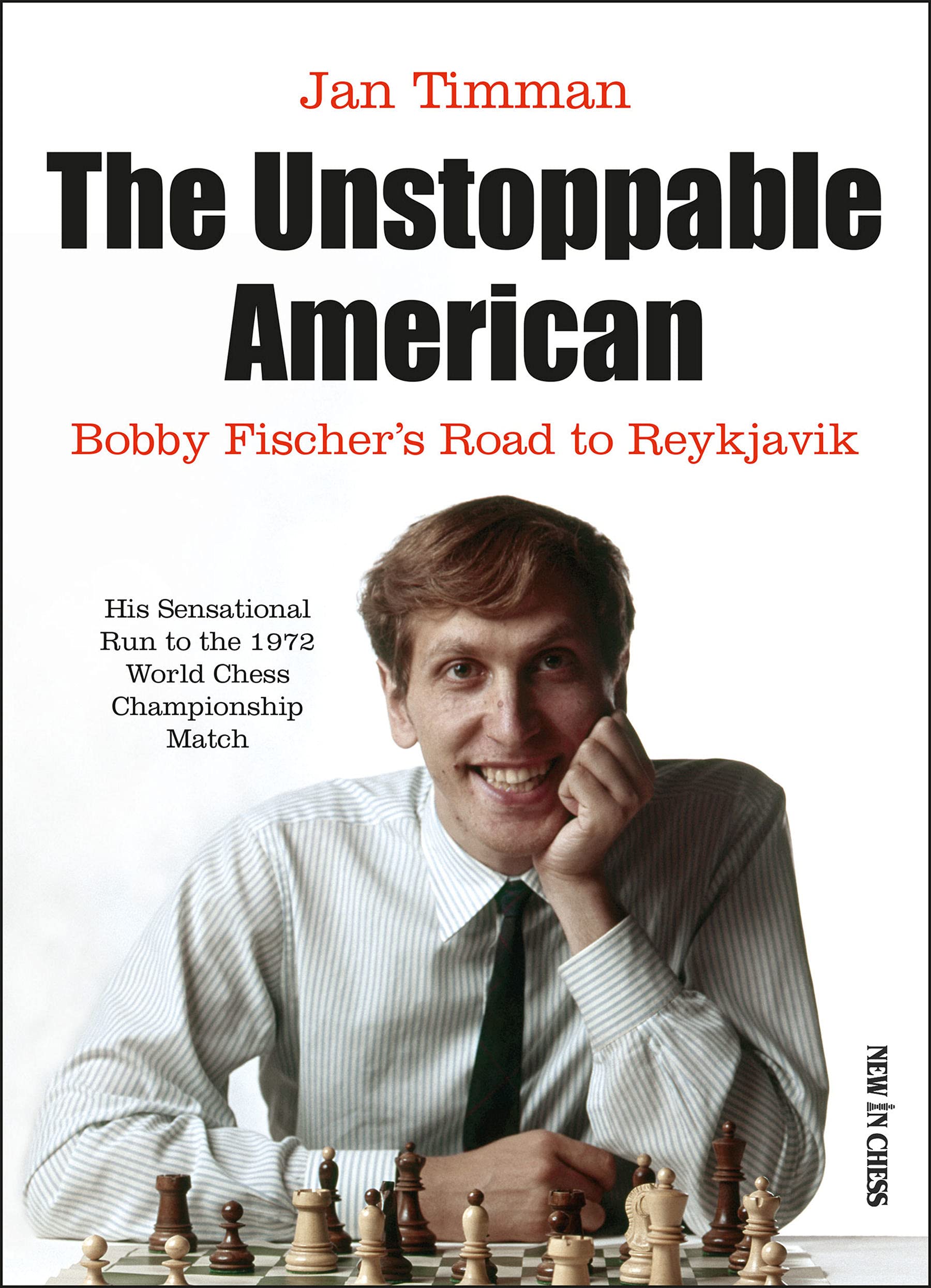

From the publisher:

“Initially things looked gloomy for Bobby Fischer. Because he had refused to participate in the 1969 US Championship, he had missed his chance to qualify for the 1970 Interzonal Tournament in Palma de Mallorca. Only when another American, Pal Benko, withdrew in his favour, and after the officials were willing to bend the rules, could Bobby enter the contest and begin his phenomenal run that would end with the Match of the Century in Reykjavik against World Champion Boris Spassky.

Fischer started out by sweeping the field at the 23-round Palma Interzonal to qualify for the next stage of the cycle. In the Candidates Matches he first faced Mark Taimanov, in Vancouver. Fischer trounced the Soviet ace, effectively ending Taimanov’s career. Then, a few months later in Denver, he was up against Bent Larsen, the Great Dane. Fischer annihilated him, too. The surreal score in those two matches, twice 6-0, flabbergasted chess fans all over the world. In the ensuing Candidates Final in Buenos Aires, Fischer also made short shrift of former World Champion Tigran Petrosian, beating the hyper-solid “Armenian Tiger” 6½-2½.

Altogether, Fischer had scored an incredible 36 points from 43 games against many of the world’s best players, including a streak of 19 consecutive wins. Bobby Fischer had become not just a national hero in the US, but a household name with pop-star status all over the world. Jan Timman chronicles the full story of Fischer’s sensational run and takes a fresh look at the games. The annotations are in the author’s trademark lucid style, that happy mix of colourful background information and sharp, crystal-clear explanations.”

Where does history start? I’ve always thought history is what happened before you were born. For those of us, like Jan Timman and myself, who learnt our chess in the 1960s, perhaps chess history is what happened before World War 2. The events of the late forties were full of names familiar to us from tournaments of our time.

This book covers Bobby Fischer’s career in the years 1970 and 1971. More like current affairs than history for our generation. We all remember it well: we were around at the time and some of us will be familiar with many of the games. But, for younger readers, Fischer’s games from half a century ago will be ancient history. If we turn the clock back another five decades we reach 1921 and the Lasker – Capablanca World Championship match. Now that really does feel like ancient history, even to me.

Fifty years on, it seems like a good time to revisit the games with the aid of today’s powerful engines and greater knowledge. Jan Timman is ideally qualified to do just that.

Readers of Timman’s other recent books will know what to expect: clear annotations based on explanations rather than variations, along with entertaining anecdotes and background colour to put the games into context.

We have all 43 games (44 if you include a win by default) from the 1970 Interzonal and 1971 candidates matches, along with a selection of 19 games from earlier in 1970.

After withdrawing from the 1967 Interzonal, Fischer played in two relatively minor tournaments the following year, and, in 1969, played only one serious game, in a New York league match. The chess world was uncertain whether or not he’d ever play again, let alone fulfil what appeared to be his destiny and become world champion. Exciting, but also worrying times.

After an 18 month absence, Bobby agreed to take part in the 1970 match between the USSR and the Rest of the World, even ceding top board to Larsen. Chapter 1 takes us from this event, via Rovinj/Zagreb, the Herceg Novi blitz and Buenos Aires, to the Siegen Olympiad.

In round 7 of Rovinj-Zagreb, Fischer was black against one of the tournament’s lesser lights, the Romanian master Ghitescu.

Timman informs us: It has never been brought up before, but Fischer was demonstrably lost in this game, after having taken too much risk.

Here’s the critical position with Ghitescu to play his 23rd move. Where would you move your rook?

The exchange sacrifice 23. Rf4! would have been very strong. Black cannot accept the sacrifice, because he would have been strategically losing. Also after 23… Rg8 24. Re4 Rae8 25. Rf1, White is winning.

I may be wrong but I would have thought Rf4 would be automatic for master strength players today. Wouldn’t it also have been automatic for, say, Petrosian, back in 1970?

Instead, the game continued 23. Rd3 Rad8 24. Ng3 (24. b3 would have maintained the advantage) 24… Ba6, when Fischer took control of the game, eventually bringing home the full point. If he’d lost that game, perhaps chess history would have been very different.

Here’s the complete game.

The strategic insights Timman brings to positions like this are, for me, what makes this book so instructive. Here’s another example: Gligoric – Fischer from Siegen, with Gligoric to make his 39th move.

It’s not dissimilar to the previous example, and indeed both positions arose from King’s Indian Defences. Here, a white knight is fighting against a dark-squared bishop outside the pawn chain.

White could have obtained a winning position with 39. Nb1!. The strategic plan is simple: White is going to bring his knight to c4 and install his king on g4. Black has nothing to offer in exchange; his doubled c-pawn will be blocked, and his pieces are barely able to display any activity.

Again, the complete game:

Chapter 2 covers the 1970 Interzonal at Palma, Mallorca. You won’t find very many brilliant miniatures in this book, but Fischer’s win against Rubinetti is an exception.

Chapters 3-5 offer Fischer’s 6-0 shutouts against Taimanov and Larsen, and the final match against former champion Tigran Petrosian.

This position interested me. Any well-read player from my generation will recognise this as coming from the 7th Fischer – Petrosian game, where Bobby played 22. Nxd7+, a move garlanded with various numbers of exclamation marks by many commentators both at the time and later.

Here’s what Timman has to say.

The praise with which this move has been showered is unbelievable. Byrne commented: ‘This exchange, which wins the game, was completely overlooked by the press room group of grandmaster analysis. Najdorf, in fact, criticized it(!), suggesting the incomparably weaker 22. a4.’

Kasparov, too, was full of praise. ‘A brilliant decision, masterfully transforming one advantage into another (…) Petrosian was obviously hoping for the “obvious” 22. a4 Bc6 23. Rc1 Nd7 24. Nxd7+ Bxd7 with possibilities of a defence.

In Chess Informant 12, Petrosian himself and Suetin give two ‘!’s to the text move.

True, not all commentators were so pronounced in their praise. Spassky and Polugaevsky limited themselves to the conclusion that White exchanged one advantage for another and didn’t give an ‘!’ to the move.

However, the general drift was that Fischer had done something highly instructive, adding a new facet to strategic thinking in chess. I was very impressed at the time, but I also had doubts. There were no computers yet, and young players looked to the great players on the world stage as their examples. So, Fischer must have understood it better than I did.

Yet, I am almost certain that in this position, or a similar one, I would have opted for Najdorf’s move. And almost half a century after the event, it turned out that the Argentinian had simply been right!

Timman goes on to demonstrate that, indeed, 22. a4 is clearly winning, whereas Fischer’s 22. Nxd7+ Rxd7 23. Rc1 would have given Petrosian defensive chances if he’d chosen 23… d4 rather than the passive Rd6.

See for yourself:

What comes across from this book is the remorseless power and logic of Fischer’s play in this period, as well as his determination to play for a win in every game. Short draws were never on his agenda.

In the past, there was a tendency to annotate by result or reputation, and this seems to have been what happened here. These days, we can all switch on Stockfish and annotate by computer, while neglecting the human, the practical element.

Timman’s annotations, both here and in his previous books, strike me as getting the balance just about right. Call me old-fashioned, but I’d rather have verbal explanations than long engine-generated variations.

Older readers will enjoy reliving memories of the golden days of the Fischer era, while younger readers will learn a lot of chess history. Players of all levels will benefit from the annotations, which, because of their lucidity, are accessible to anyone from, say, 1500 upwards.

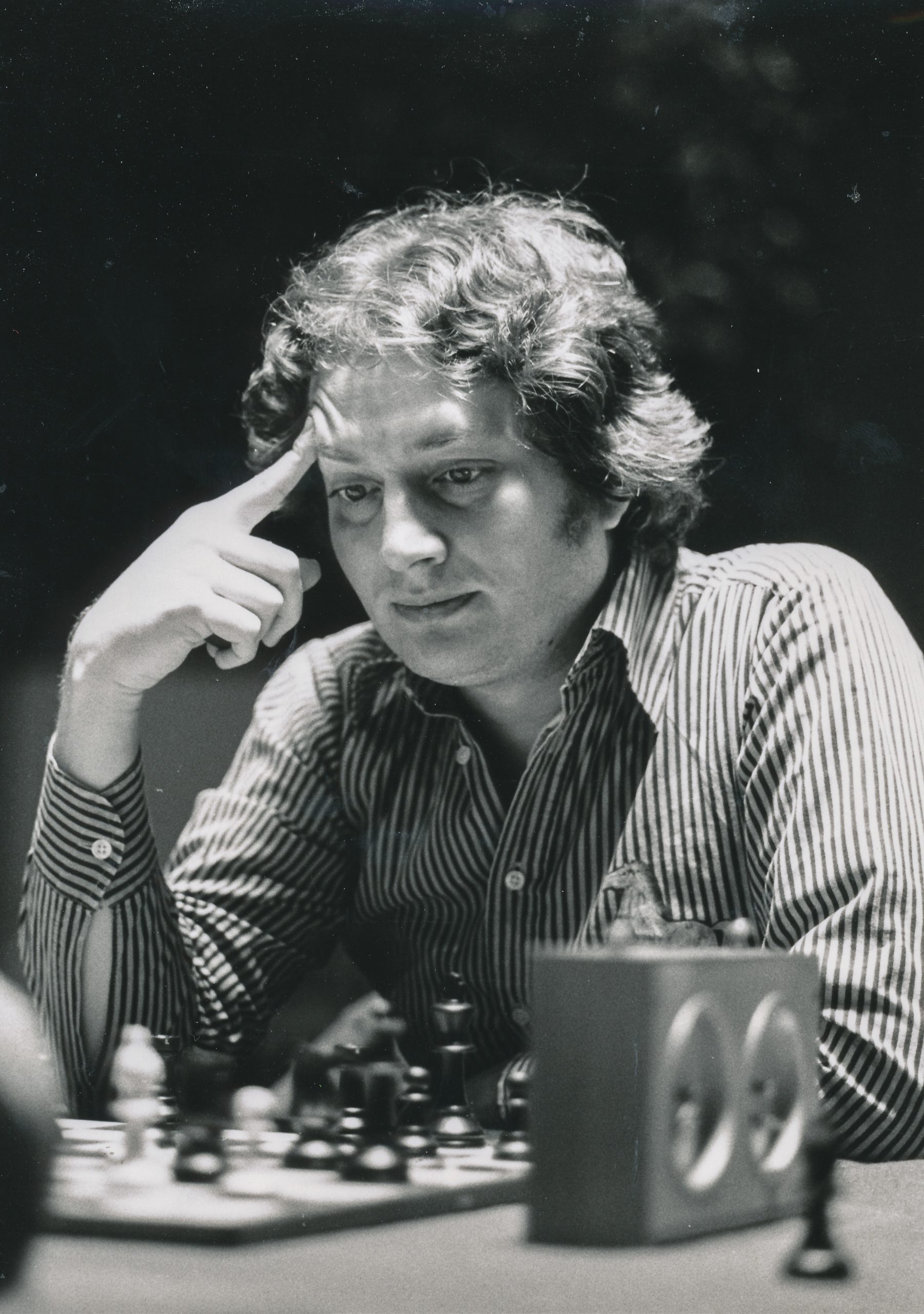

The many anecdotes add much to the book, although serious historians might feel frustrated that they’re not always sourced. There are also several pages of photographs: while their quality, as they’re printed on matt paper, isn’t perfect, they’re still more than welcome.

There are a few typos and mistakes regarding match scores and tournament crosstables which more careful proofing might have picked up, and the English, in one or two places (you may have noticed this from the extracts I quoted), might have been more idiomatic. Slightly annoying, perhaps, but this won’t really impede your enjoyment of the book.

In spite of these slight reservations, this is an excellent book which is warmly recommended for players of all strengths. Next year will see the 50th anniversary of Fischer – Spassky. Might we hope that Timman will cover this match in a future volume?

One last thought: I wrote at the beginning of this review about how people of different ages have different perspectives of history. If Capablanca and Alekhine had been granted long lives, they would have lived to see these games. What would they have made of them? What would they have made of Bobby Fischer?

Richard James, Twickenham 10th August 2021

Book Details :

- Softcover: 256 pages

- Publisher: New In chess (17 May 2021)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9056919784

- ISBN-13:978-9056919788

- Product Dimensions: 17.27 x 2.54 x 23.62 cm

Official web site of New in Chess