If, like me, you enjoy family and social history, you’re probably a fan of David Olusoga’s documentary series A House Through Time.

Here’s an idea for a new series: A Book Through Time.

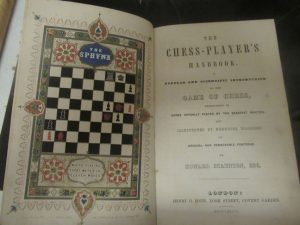

If you’ve read my article about Henry George Bohn, you’ll have seen this before. It’s my first edition of Staunton’s Chess-Player’s Handbook.

If you’ve read my article about Henry George Bohn, you’ll have seen this before. It’s my first edition of Staunton’s Chess-Player’s Handbook.

I acquired this as a gift from a pupil’s mother, who ran an antiques shop in Hampton Wick.

There are also two inscriptions. The second is ‘Peter Elliott’: there were several people of this name in this area, none of whom mean anything to me.

There are also two inscriptions. The second is ‘Peter Elliott’: there were several people of this name in this area, none of whom mean anything to me.

We can, however, identify the first inscription: WD Hutchings Stoke on Trent 1882.

Who was Mr Hutchings? Was he a chess player who required a handbook, or did he just have a casual interest in the game? What was he doing in Stoke on Trent? How did the book reach Hampton Wick?

It transpires he was William Dobell Hutchings, the son of Frank Hutchings and Mary Laskey (close, just one letter out) Dobell, and was born in Exeter in 1844, making him three years older than the book. His mother doesn’t seem to have been related to Hastings chess player Herbert Dobell.

We first pick William up in the 1851 census, where he appears to be at a local boarding school. Upper middle class families like the Hutchings’ started boarding their children young in those days. By 1861 he’s at home with his parents and many siblings: we learn that his father is a solicitor, and young Bill is apprenticed to a banker.

1871 finds him in West Ham, living in a boarding house and working as a banker’s clerk. A few months later, though, he turns up at Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, on the edge of the Cotswolds, between Bristol and Stroud, where he marries local girl Ann Clark. The happy couple move back to West Ham, and, a year, later, welcome their daughter Alice Emma into the world. Two years later, a son, Frank Henry, is born, but, tragically, he dies back in Devon at the age of only 3.

At some point over the next few years he gains a promotion and, now in a managerial role, moves to Stoke on Trent, where, by 1881, he’s doing well enough to employ two servants. Later in the year, their third child, a son named William Dobell after his father, is born. The following year he comes across a second-hand copy of the first edition of Staunton’s Chess Player’s Handbook: the copy I have in front of me as I write these lines. At this point the book was 35 years old, just three years younger than its new owner.

He doesn’t remain in the Potteries very long, though. He soon gets a new job – in Leicester. I wasn’t planning to return to my father’s home town so soon, but here we are. Perhaps inspired by Staunton’s best-seller, he joins the local chess club.

The Leicester Journal of 22 February 1884 reported on the Leicester Chess Club AGM, which saw WD Hutchings elected to the committee. After the meeting, Leicester played a match against their regular opponents from Nottingham, which they lost by 8 points to 5.

There, on the top board, was Martin Luther Lewis, winning his game against Sigismund Hamel, with William Withers on board 5 scoring a draw. Hutchings wasn’t playing in this match but for the next decade he played regularly on a middle board for Leicester in matches against other midland clubs. EdoChess doesn’t rate him highly: between about 1600 and 1650: merely an average club player.

However, it’s always useful to have a bank manager in your club. As we in the present day Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club can testify, they make excellent treasurers, or, in the case of William Hutchings, it appears, auditors.

So here, then, we have someone who wasn’t an outstanding player, but who played an important role in the life of his club by taking part in matches regularly, serving on the committee and auditing their accounts. One of the purposes of these articles is to demonstrate that average club players like Bill are just as important to the chess community as masters and grandmasters. I’m honoured to possess a book which he once owned. But how did it reach Hampton Wick?

The 1891 census finds William, Ann, their two children and two servants living in New Walk, Leicester.

From New Walk – Story of Leicester:

New Walk is a rare example of a Georgian pedestrian promenade. Laid out by the Corporation of Leicester in 1785, the walkway was intended to connect Welford Place with the racecourse (now Victoria Park) and is said to follow the line of a Roman trackway, the Via Devana. Originally named “Queen’s Walk”, after Queen Charlotte, consort of George III, it was eventually the popular name of the “New Walk” that survived. Almost a mile long, New Walk has been a Conservation Area since 1969, ensuring its unique character is protected.

Houses built at the lower end of New Walk in the 1820s were the first on the walkway and were designed as “genteel residences” for the families and servants of businessmen and professionals. Development was controlled however to protect the public’s enjoyment of the walkway. Houses had to be at least ten yards from the Walk, fenced off by iron railings, and there was no access for carriages onto New Walk itself. In 1840 one resident described New Walk as “the only solely respectable street in Leicester”.

The houses around central New Walk date from the 1850s and 1860s and would have been the homes of merchants, manufacturers and professionals. Residents in the 1880s included Josiah Gimson, head of a large engineering firm, whose home (No. 112) is now part of the Belmont Hotel.

Last to be developed along New Walk were the large Victorian houses of its upper section (dating from the 1880s). Many were designed by the architect Stockdale Harrison. They reflect the growing prosperity of Leicester’s business and professional classes who preferred to live away from the town centre.

So William was doing very well for himself, but a few years later he was on the move again. The 1901 census finds him in Sutton Coldfield, still working as a bank manager. His children have now left home, but he still employs two servants, one the appropriately named Alice Bishop. After 1894 his name disappears from the chess records, with one exception. In 1903 Blackburne gave one of his many simultaneous displays (we’ll visit others in later articles) at Birmingham Chess Club. This was William’s moment of chess glory: he was one of three players who managed to defeat the visiting master. Well played, Sir! It’s always good to go out on a high.

It was soon time for him to hang up his cheque books and retire from managing banks. Where did he retire to? He sought the good life in Surbiton. The 1911 census finds him at 3 Walpole Road, just off the Upper Brighton Road, which I’ve passed many times on my way to chess matches. He’s there with his wife and, again, two servants: a parlourmaid and a cook.

He was probably unaware that a five minute walk down the road would take him to a boarding house named Mountcoombe, where he could have met another South Devon born chess enthusiast, the celebrated problemist Edith Baird.

So I’d imaging that William’s Staunton first edition found its way from Stoke on Trent to Surbiton via Leicester and Sutton Coldfield. I’m sure he’d have shown it to his antique dealer friend William Withers, who, you will recall, had played (and lost horribly) to my very distant relation Arthur Towle Marriott.

Perhaps his belongings were sold off after his death in 1923. Or perhaps the book was inherited by his son, a stockbroker, who had also moved down to London. In 1911 he was living in Old Deer Park Gardens, Richmond, just off Kew Road very close to the London Welsh Rugby Club where Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club used to meet. A 35 minute walk through the town centre, passing the location of William Harris’s chemist business, and over Richmond Bridge, would have taken him to the site of the recently demolished residence of Henry George Bohn, the publisher of his father’s book. By 1939 he’d moved 3/4 mile to the north, to Hatherley Road, Kew. I pass both these roads regularly on my way to Kew Gardens. William junior died in 1957, so perhaps Peter Elliott acquired the book at that point.

Thank you for the book, William Dobell Hutchings, and thank you also for your part in the history of our wonderful game. Your contribution might have been relatively modest, but it was still important, and without doubt valued by Martin Luther Lewis, William Withers and your other chess-playing Leicester friends.

I have a few other inscriptions in second-hand books to write about another time. If you have any yourself you’d like me to research, do get in touch and I’ll see what I can do.