From the author’s introduction:

I was lucky enough to play against six world champions and several top players in my modest chess career, but the greatest player I feel privileged to have known, to have spent time with him, was Miguel Najdorf, “El Viejo”.

This is a chess book, with 275 commented games, it covers all his chess career, but it has also many stories. Najdorf was the most important Argentinean chess player, and he was an exceptional person. Oscar Panno said that Najdorf reminded him of Don Quixote, in the part of the book where he tells Sancho Panza, “Wherever I am, that is where the head of the table is going to be”. He successfully overcame the most terrible setbacks, as few are capable of doing. Writing about Miguel Najdorf is one of my greatest pleasures as a chess journalist and writer!

Zenon Franco Ocampos, April 2021.”

“Zenon Franco Ocampos was born in Asuncion, Paraguay, May 12, 1956. From there he moved to Buenos Aires until 1990. Since 1990 he has lived in Spain. Zenon authored 28 chess books which have been published in six languages. In addition to his books, he has served as a chess columnist for the Paraguayan newspapers ‘Hoy’ and ‘ABC Color’ for 17 years. He has written a chess column for magazines from Argentina, Italy, and Spain. Zenon is most respected Grandmaster and FIDE Senior Trainer. He has participated in 11 chess Olympiads and will now captain the Paraguay team during the Moscow Olympiad 2021. His greatest achievements winning gold medals at the Olympiads of Luzern, 1982 and Novi Sad, 1990. His most successful students were GM F. Vallejo Pons and IM David Martinez Martin, Spanish editor of Chess24.com.”

If you hear the name Najdorf, what immediately comes to mind? The Najdorf Variation of the Sicilian Defence, I’d guess.

Something like this, perhaps, although it transposes into a Scheveningen.

It wasn’t Najdorf who originated the idea, though. He’d been playing it since the mid 1930s, perhaps having been shown it by the Czech master Karel Opocensky

In this important game, from the last round of the 1948 Interzonal, he was playing black against Dr Petar Trifunovic, who was considered almost unbeatable with the white pieces, but who needed a win to have any chance of qualifying for the Candidates Tournament.

Here’s Najdorf on his choice of 5th move:

In those days the line had scarcely been investigated and I emphasise that Dr Trifunovic was famous for his theoretical knowledge.

And after the game:

I was pleased with this game against Trifunovic, because it was a battle of ideas and plans to bring about a balanced game.

His attempt to attack is not successful and with an extremely audacious manoeuvre he exposes his queen, granting me a very tiny chance. Maybe he didn’t foresee the consequences. What is certain is that, from that moment on, Black takes control and forces and forces, until resignation.

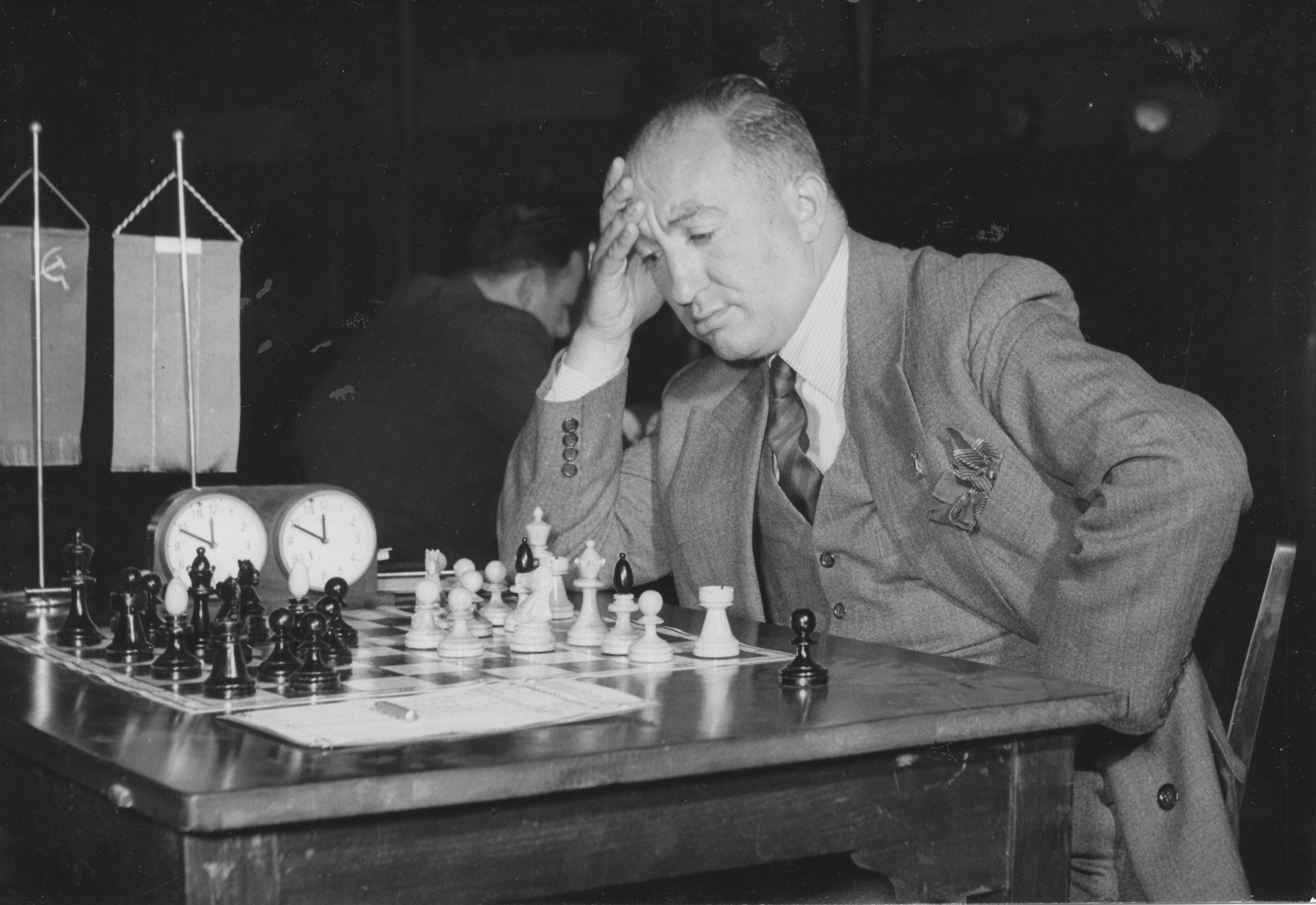

But there was a lot more to Najdorf than his variation. He was a colourful personality who had a long and eventful life, and a chess career lasting 70 years: from 1926 to 1996, playing everyone from Capablanca, Alekhine and Rubinstein through to Fischer, Karpov and Kasparov. Jeff Sonas (Chessmetrics) puts him in the world top 10 for the decade or so after World War 2, and at number 2, with a highest rating of 2797, for most of the period between 1946 and 1949.

If you’re from my generation you may know quite a lot already, but younger readers may not.

Here’s your opportunity to put that right: Zenon Franco Ocampos and Thinkers Publishing offer you 720 pages on the life and games of El Viejo (the old man, as he was often known, especially by himself), with 275 annotated games and extracts, along with much historical information and a wealth of hilarious anecdotes.

We start with an unfinished book written by Najdorf himself, with thirteen annotated games, before moving onto an account of his early life.

Najdorf was born in 1910 in Warsaw, named Moishe Mendel, although the Polish version, Mieczyslaw, was also used, but when he settled in Argentina, he became Miguel. He learnt the moves at the relatively late age of 14 from a friend’s father, but his parents were unhappy with his chess obsession.

He soon gained a reputation as a highly talented but erratic player, capable of producing brilliancies such as the much anthologised ‘Polish Immortal’ against Gluksberg, where he sacrificed all his minor pieces, but Najdorf himself preferred this game (the date, venue and name of his opponent are all uncertain).

Najdorf was playing for Poland in the 1939 Buenos Aires Olympiad when World War 2 broke out, and, like a number of other European Masters, decided to stay there.

This was a decision that saved his life: his wife, daughter, parents and four brothers were all murdered in the Holocaust. You won’t read a lot about this here, though. As Franco points out, this is a games collection rather than a biography, and he directs you to Najdorf’s daughter Liliana’s book for further information.

Further chapters look at the war years, when he settled in Argentina, the decade or so after the war when he was a world championship candidate, the years up to 1982 when he was still competing regularly at the top level, and the last phase of his career, up to his death in 1997.

You might be disappointed if you’re expecting a lot of Sicilian Najdorfs. There aren’t very many – and he didn’t play it all that often. A large proportion of the games have Najdorf playing White, where he usually opened 1. d4, so you’ll get a lot of queen’s pawn games. Before the war he often adopted a Colle-Zukertort set-up, but later preferred more critical variations. He was particularly impressive playing positions with an isolated queen’s pawn: study of these games will be beneficial if you enjoy this pawn formation yourself.

This position is from Najdorf – Kotov (Mar del Plata 1957), where our hero chose 21. Bd1!

An unusual move, very imaginative, which brings White a quick victory. This is strong, but not the most forceful.

Many years later, Igor Zaitsev indicated that the strongest move was 21. Bc2!!, with a potential fork on f7 after Rxc2.

After 21. Bd1 Qa5, Najdorf won quickly, but after 21… Rc7, Franco points out the computer move 22. a5, freeing a4 for the bishop.

Here’s the complete game.

Najdorf was also renowned for his prowess on both sides of the King’s Indian Defence.

This game, the first brilliancy prize winner at the 1953 Candidates’ Tournament, is of considerable historical importance, played at a time when players like Bronstein and Najdorf were developing the King’s Indian Defence into a dangerous counter-attacking weapon.

Franco sensibly combines Bronstein’s and Najdorf’s annotations from their tournament books.

If you have a particular interest in the King’s Indian Defence, either as a player or from a historical perspective, you’ll enjoy a lot of the games here.

So what you get in this book is a lot of great chess, many of the games annotated by Franco, but others with annotations from a variety of sources, including, in many cases, Najdorf himself. He also adds modern engine improvements where appropriate. As you’d expect from such an experienced author, the notes are pitched at just the right level: approachable for anyone from 1500 to 2500 strength.

Then you have the anecdotes. Najdorf was an ebullient character, who barely seemed to stop talking, even during his games. Kotov famously asked the (rhetorical) question: should you imitate Botvinnik or Najdorf? He was one of the most popular figures in chess, extrovert, charming, passionate about both chess and people, but sometimes also annoying.

Back in 1937, during the Polish Championship, another player allegedly asked him what the time was. On the first two occasions, lost in thought, he made no reply. On the third occasion he consulted his watch and replied, after some consideration, “d2-d4”.

On a long chartered train journey in Argentina in 1957, Najdorf constantly walked up and down the carriage, talking to all the other players, who wanted to get some rest, and not taking any hints. At length Keres shouted to Kotov at the other end (in English so that everyone would understand) “Alexander, how long have you known Najdorf?” “I think I have known him since 1946.” Keres congratulated his colleague on his good fortune: “I have known him since the Warsaw Olympiad in 1935.”

Pal Benko told the story of how he adjourned a pawn up in a rook ending against Najdorf. He didn’t have time to analyse it, but Najdorf insisted it was a draw and not worth playing out. He wouldn’t stop talking so eventually agreed to shut him up. He then went back to his room and saw that the position was in fact easily winning for him. Outraged, he confronted his opponent:

“Why did you lie to me like that? What the hell’s wrong with you? Why didn’t you let me think?” He just smiled, put his arms round me and said, “Don’t worry about it. Come on, I’ll take you to a nice nightclub.” How could you stay mad at a guy like this?

All entirely believable for anyone who knew Najdorf, but Franco looked at the game, and found it really didn’t match the story. He’s very good at checking out anecdotes like this.

So what we have, then, is 720 pages about an important figure in the chess life of the mid 20th century: great games expertly annotated, a lot of chess history, and a lot to make you laugh as well. Good use is made of various sources, and these are always credited so we know where to go if we want more information about Najdorf. What’s not to like?

Unfortunately, there are problems regarding the production. The book almost seems to be in two halves. The first part of the book provides tournament tables (sometimes with unnecessary errors), but by the time he starts playing in top level tournaments these disappear without explanation. Yes, I know they’re readily available elsewhere but I find the inconsistency rather annoying. We get group photographs, which is great, but the players are often not identified. There’s a lack of proper indexing as well: there’s a list of games in the order in which they appear in the book, but no indexes of players or openings. A summary of Najdorf’s tournament and match results at the end of the book is also something I’d expect from a chess biography of this nature.

To take just one example of a careless factual error, we’re told that Franciszek Sulik was champion of Australia nine time (sic). If he had been, I’d have heard of him. In fact he was champion of South Australia nine times. The typo again is only too typical. There are far too many to be acceptable for a book of this nature. Like so many chess books published these days, it really needed someone else to check it through one more time.

Perhaps the book would have been better as two volumes, or maybe just as a games collection without the historical background. I can’t help feeling the publishers, skilled as they are in producing other types of chess book, were slightly out of their comfort zone here.

It’s an important book, an entertaining book, and in many ways an excellent book which will be enjoyed by readers of all levels, especially those with an interest in chess history. My reservations about the production values, though, preclude a wholehearted recommendation.

Richard James, Twickenham 19th October 2021

Book Details :

- Softcover: 720 pages

- Publisher: Thinkers Publishing; 1st edition (2 September 2021)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9464201134

- ISBN-13:978-9464201130

- Product Dimensions: 16.51 x 1.27 x 23.5 cm

Official web site of Thinkers Publishing