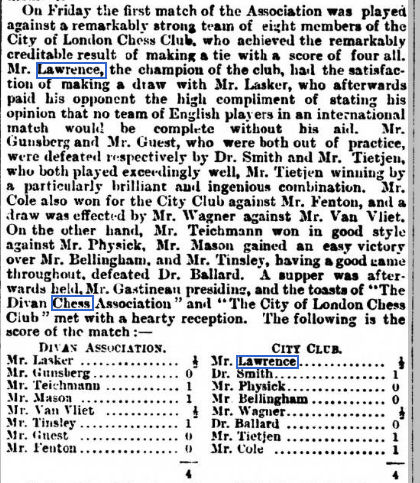

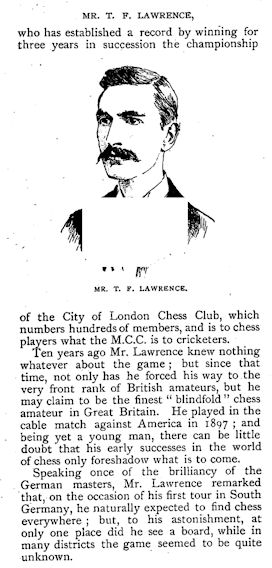

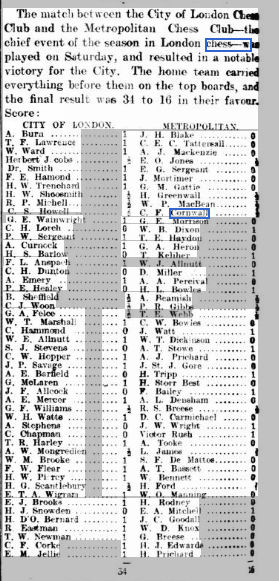

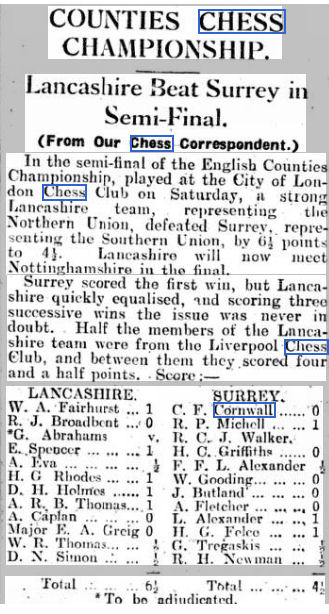

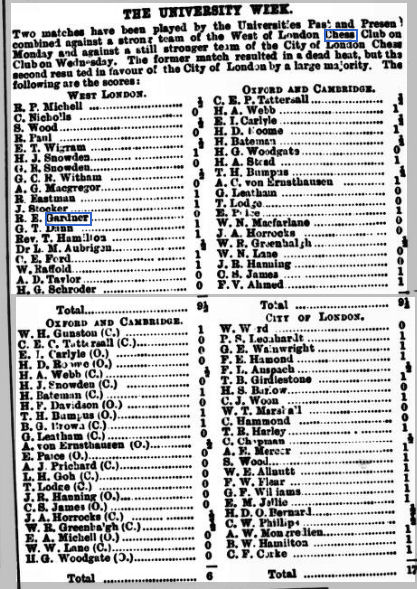

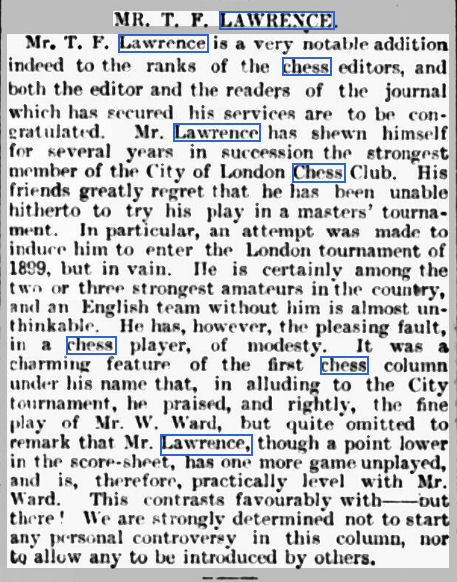

We left Thomas Francis Lawrence in 1901, living in Westminster with his mother and brother, and now established as one of England’s leading players, having won the prestigious City of London Chess Club Championship on five occasions and represented his country in the Anglo-American cable matches.

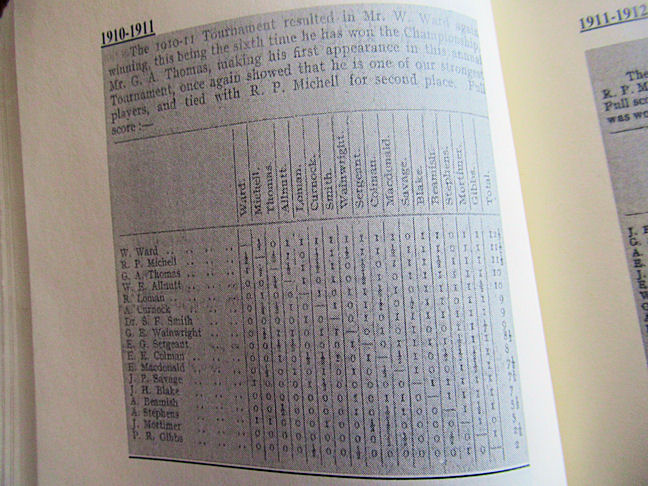

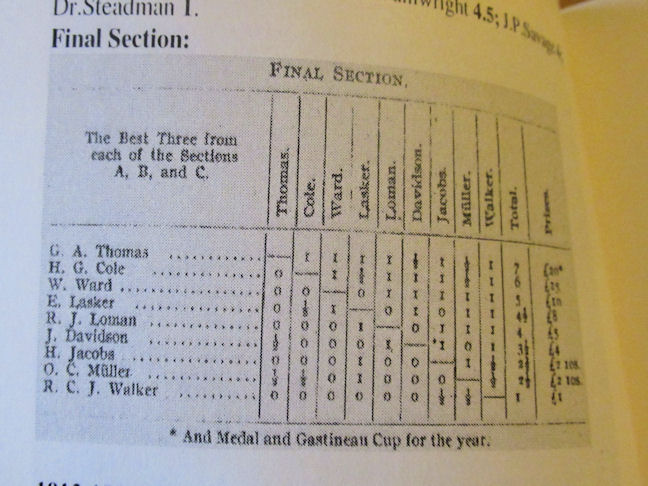

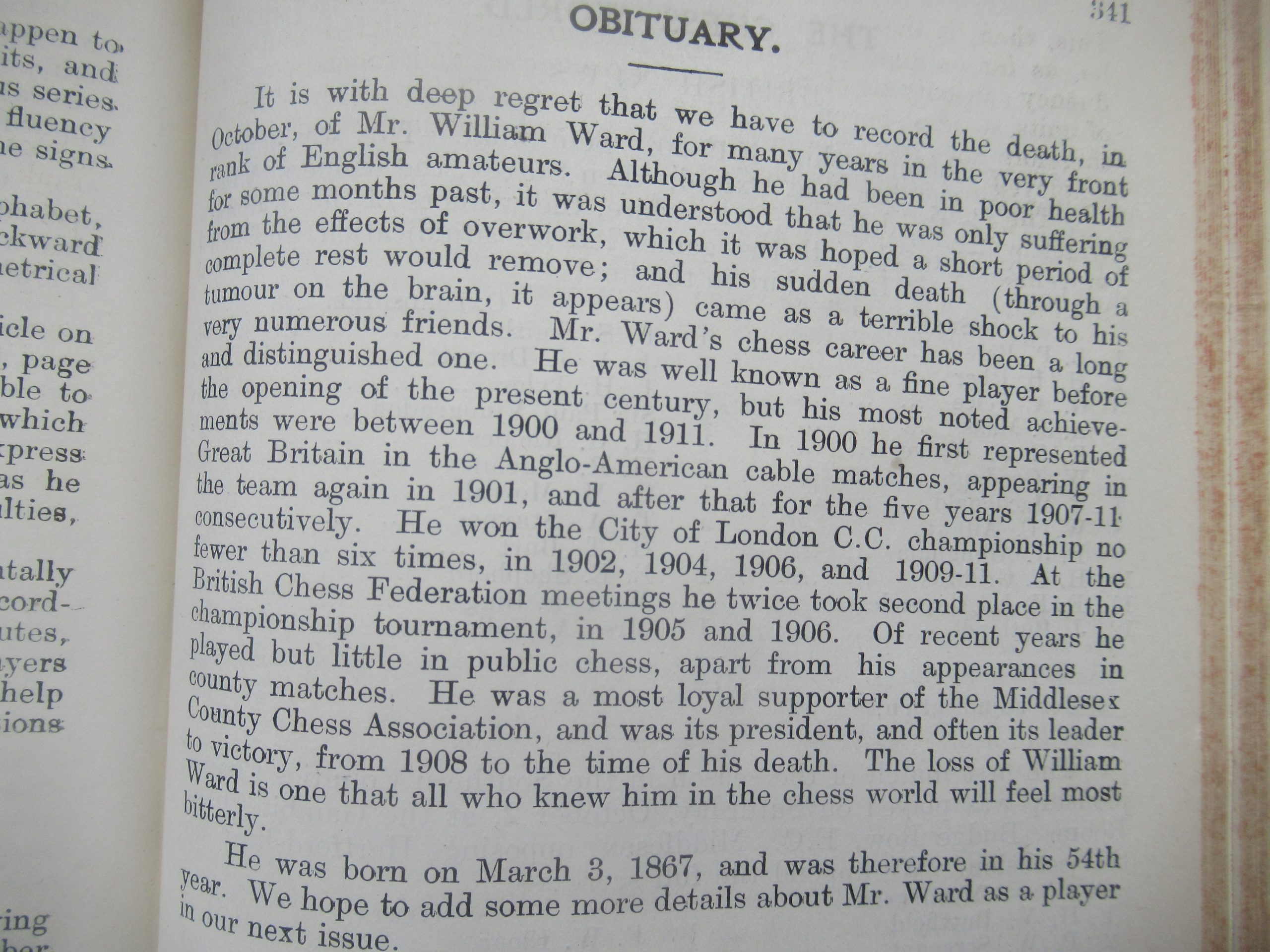

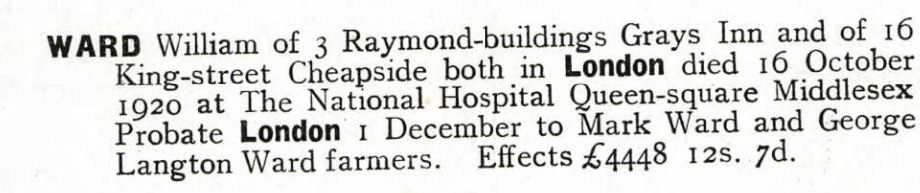

In 1901-02 William Ward won the City of London Club Championship for the first time, with Lawrence in second place. He won the title back the following year, his sixth victory.

In 1902 Lawrence was appointed chess columnist for The People: his columns are exemplary for the time, including, as was standard, the latest chess news, a recent tournament game and a problem along with lists of those who had submitted correct solutions to the previous week’s problem. Along with his work for the Prudential and his regular chess playing commitments, he must have been pretty busy.

He didn’t play in the 1901 cable match, but in both the two following years he was on top board against the great Harry Nelson Pillsbury, drawing both games. Here’s the 1903 game: click on any move for a pop-up board.

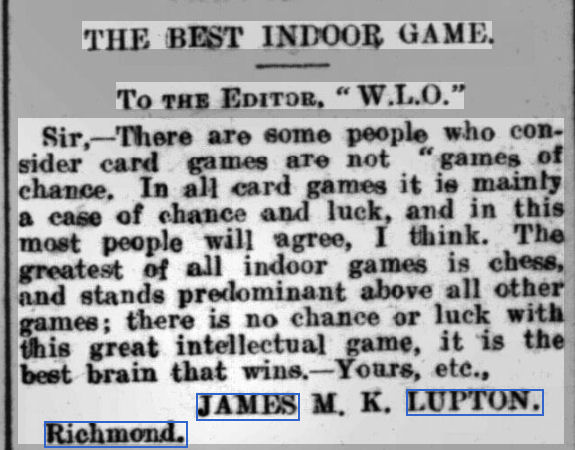

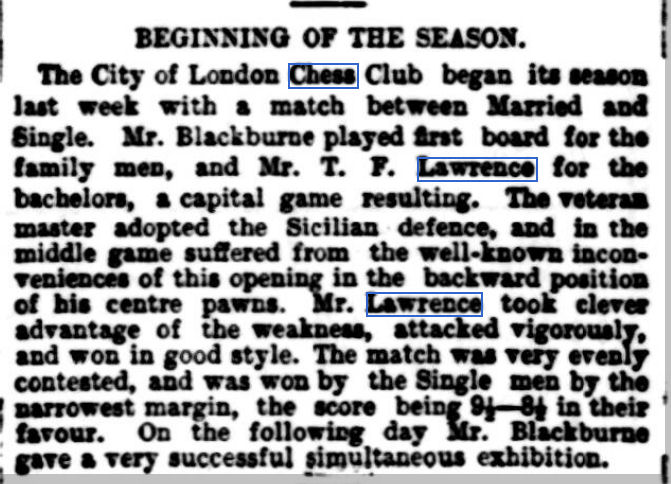

It was common at the time for clubs to open their season with a novelty match. Richmond Chess Club, as we’ve seen, staged matches between the residents of Richmond and Sheen. Some clubs played matches between smokers and non-smokers, or, in this case, married men against bachelors, and in 1903 Thomas Francis Lawrence was on top board for the singletons against the illustrious veteran Joseph Henry Blackburne.

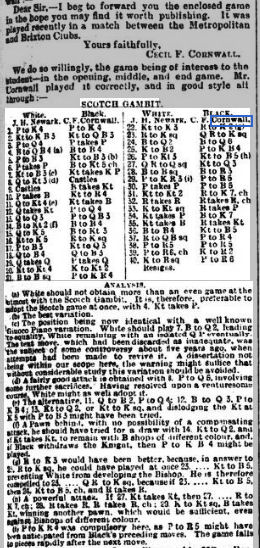

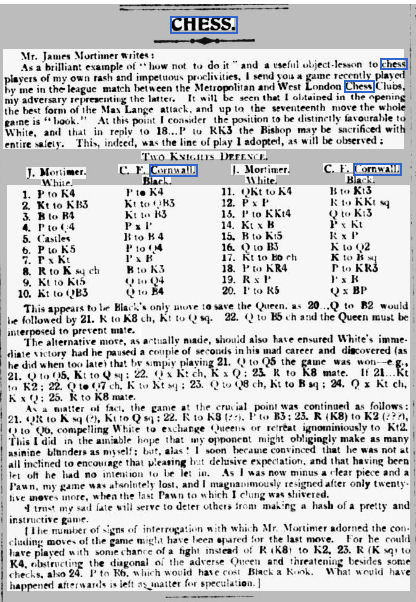

Here’s the ‘capital game’. Blackburne’s loss, according to Stockfish, was caused by trading bishops on move 22, allowing the white knight into play.

Sadly, shortly after this game his mother, Esther Jane (Izard) Lawrence, died at the age of 70, necessitating Thomas’s withdrawal from the City of London Club Championship, in which William Ward took the title for the second time. The burial record confirms that at some point after the 1901 census the family had moved from Westminster to 132 Palewell Park, Mortlake (it would now be considered East Sheen), one of the area’s most desirable roads, close to Richmond Park. Esther was buried at St Mary the Virgin Church Mortlake, also the burial place of Queen Elizabeth I’s astrologer John Dee.

It’s worth a look at Rod Edwards’ retrospective ratings for 1903 at this point. Lawrence is ranked 54th in the world, with a rating of 2423. You’ll see Atkins (2542) and Burn (2540) ranked 13th and 14th, and then a gap to Blackburne (2451), Michell (2428) and Lawrence. Two distinguished veterans, then, and three up-and-coming young players.

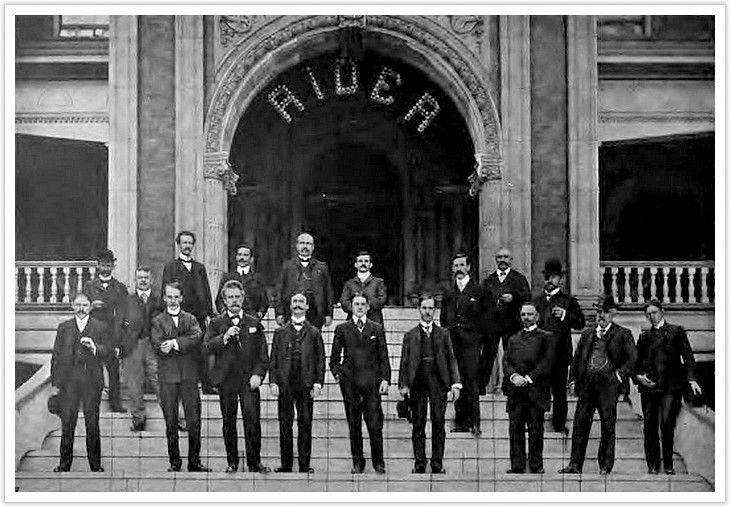

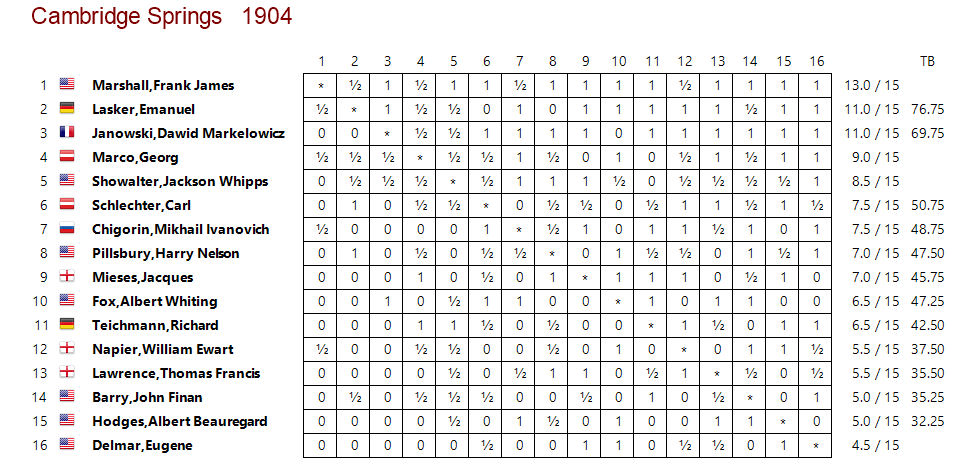

In 1904 a major chess tournament took place in Cambridge Springs, a small town in Pennsylvania noted at the time for its mineral springs. The world’s leading players were invited to take part, and it was perhaps surprising for several reasons that Thomas Francis Lawrence was one of the participants. Apart from having a busy life, his seeming modesty and lack of ambition made him an unlikely choice: indeed, he was the only one of the eight European participants with no previous experience at this level.

Here’s a group photograph with Lawrence third from the right at the back.

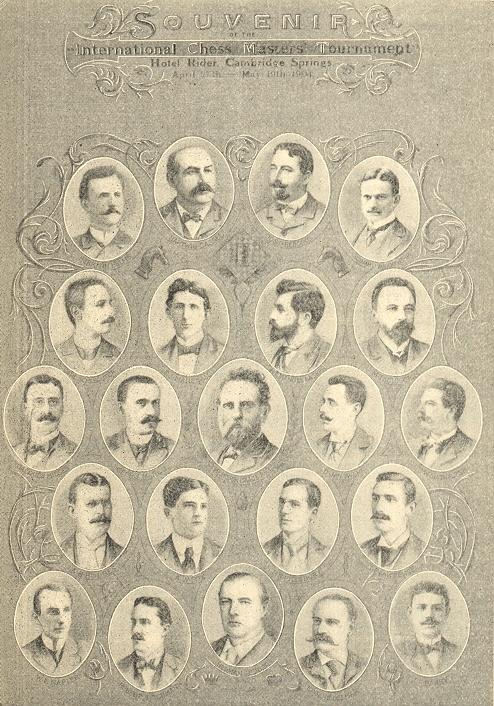

And here he is again (on the right on the fourth row down) in this rather wonderful tournament souvenir.

Lawrence scored 5½/15, about par for his (hypothetical) rating, but it could easily have been much better.

In Round 2 he could have obtained good winning chances against Delmar by trading queens on the right square instead of weakening his pawn formation. In Round 5 he lost on time in a winning position against Fox. In Round 8 he had a big advantage from the opening against Barry. In Round 10 he made an elementary one-move blunder in a drawn rook ending against Lasker. In Round 11 he missed a win against Chigorin, and then, it appears, agreed a draw after his opponent made a losing blunder. In Round 15 he took a draw by repetition in a winning endgame against Showalter.

A score of 9 rather than 5½ would have been a great success, so what, I wonder, went wrong? The pressure of the big occasion? Lack of experience at this level? Nerves? Poor clock handling? There were other lessons to be learnt: while he did well with black, his play with the white pieces was often uninspiring: he was comprehensively outplayed by Janowski, Marco, Schlechter and Hodges.

His game against Napier demonstrated that, given the chance, he was a strong attacking player.

Although Pillsbury was mortally ill with syphilis, it was still no mean feat to bring off a tactical finish against his old cable match opponent.

If you’re interested in finding out more about Cambridge Springs there’s a new book coming out later this year which sounds well worth reading. This website is also informative.

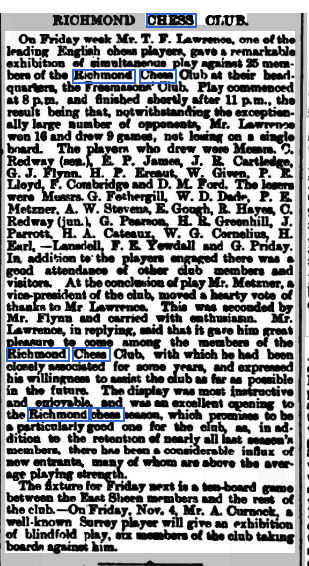

It was at this point that we first met him in our previous instalment, giving a simul at Richmond Chess Club in October 1904.

Did he, inspired by his participation at Cambridge Springs, take part in more tournaments?

The answer is ‘No’. He didn’t take part in the next three City of London Club Championships. The Anglo-American Cable Match didn’t take place, for various reasons, for three years between 1904 and 1906, so, it seems that, at this point, he was playing very little chess. Perhaps he had other things on his mind.

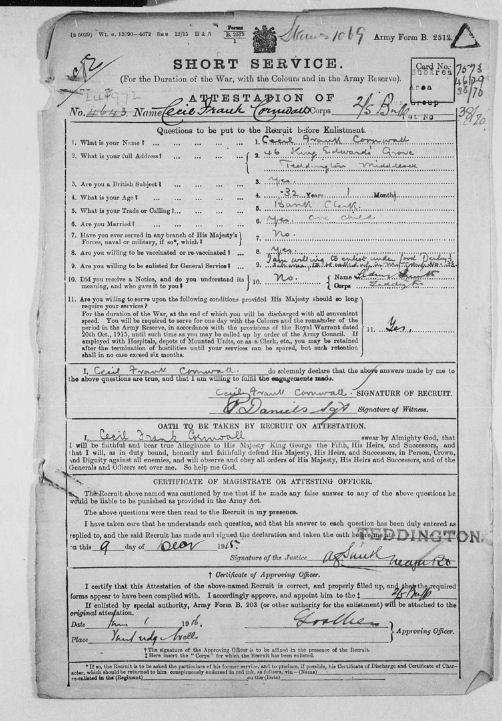

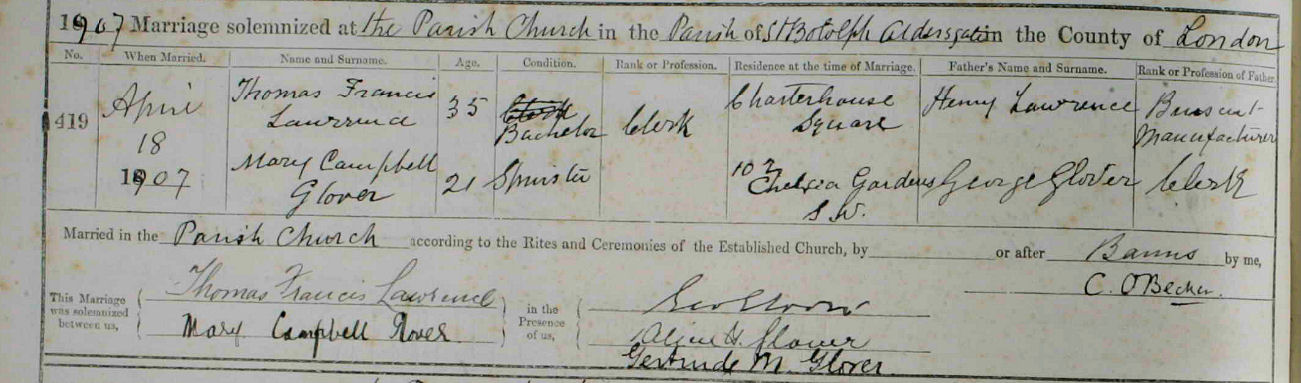

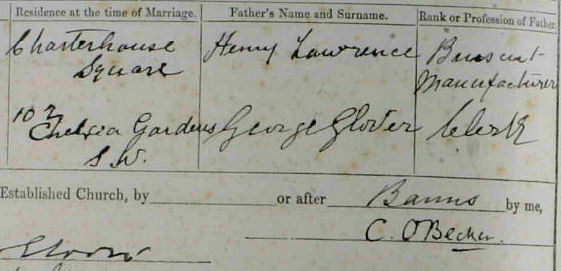

Perhaps he had a young lady on his mind. Take a look at this.

Here he is, aged 35, tying the knot with 21-year-old Mary Campbell Glover, on 18 April 1907, in St Botolph’s Church, Aldersgate, right by the Barbican and very near St Paul’s Cathedral. There are a few mysteries. We know his family owned a property in East Sheen at the time (as you’ll see shortly) but his address was given as Charterhouse Square, close to St Botolph’s. Perhaps he had a London pad, conveniently situated a few minutes’ walk from the new Prudential headquarters in Holborn.

Mary’s father, George Glover, was an insurance clerk and chess enthusiast: he and Thomas knew each other from the Insurance Chess Club.

There are a couple of interesting things to point out. Look at it more closely.

Look closely at Henry’s Rank or Profession. Biscuit Manufacturer? I’m not sure. When Thomas was born he was living in Velsen, where the North Sea Canal was being built. Was he manufacturing something to do with canals? Or did the construction workers need a supply of freshly baked biscuits? Any idea?

There’s something else strange. It was customary (and probably still is) to add ‘deceased’ under the father’s name in marriage registers, and, if you look at the complete page, you’ll see several examples. Thomas’s late mother Esther had claimed to be a widow on the census records between 1881 and 1901, but here’s her son implying that Henry was still alive. It was very common at the time for women who had split from their husbands to describe themselves as widows so perhaps that’s what had happened. Or perhaps Thomas had no idea whether or not Henry was still alive. Perhaps the omission of the word ‘deceased’ was just an oversight.

He had in fact returned to chess a few weeks before this happy event, taking part in the 1907 cable match, where he drew with the splendidly middle-named Albert Beauregard Hodges.

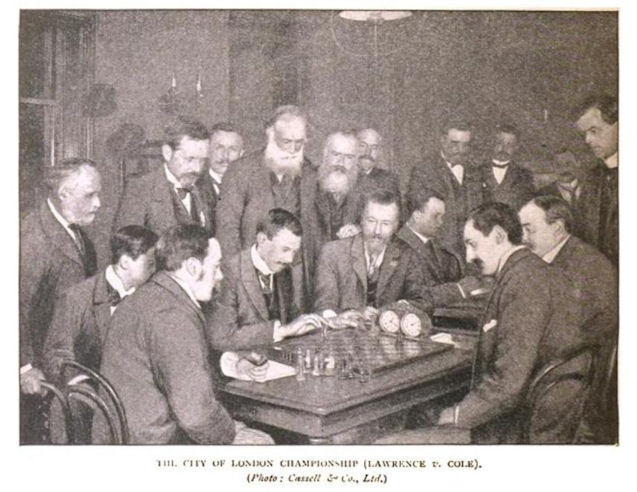

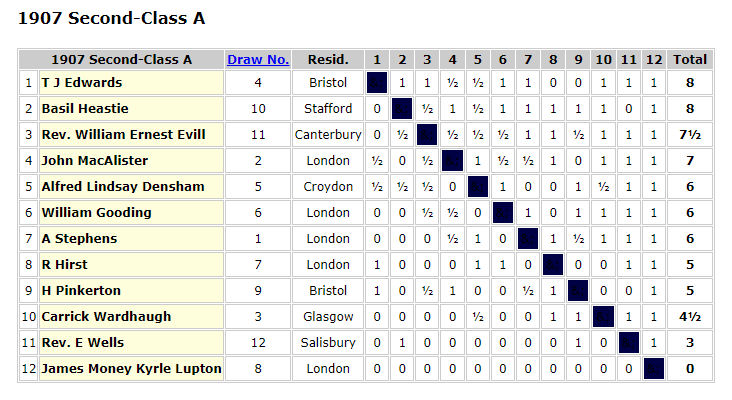

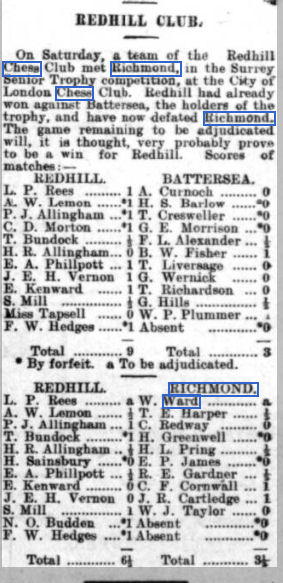

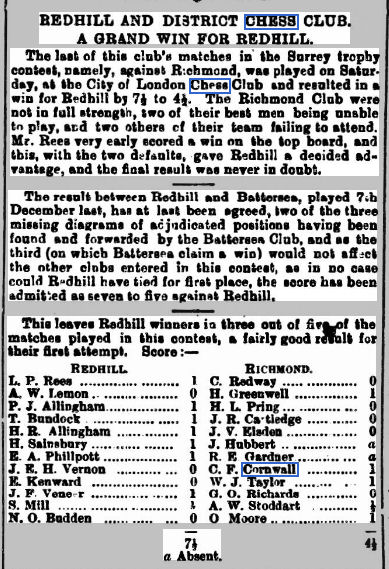

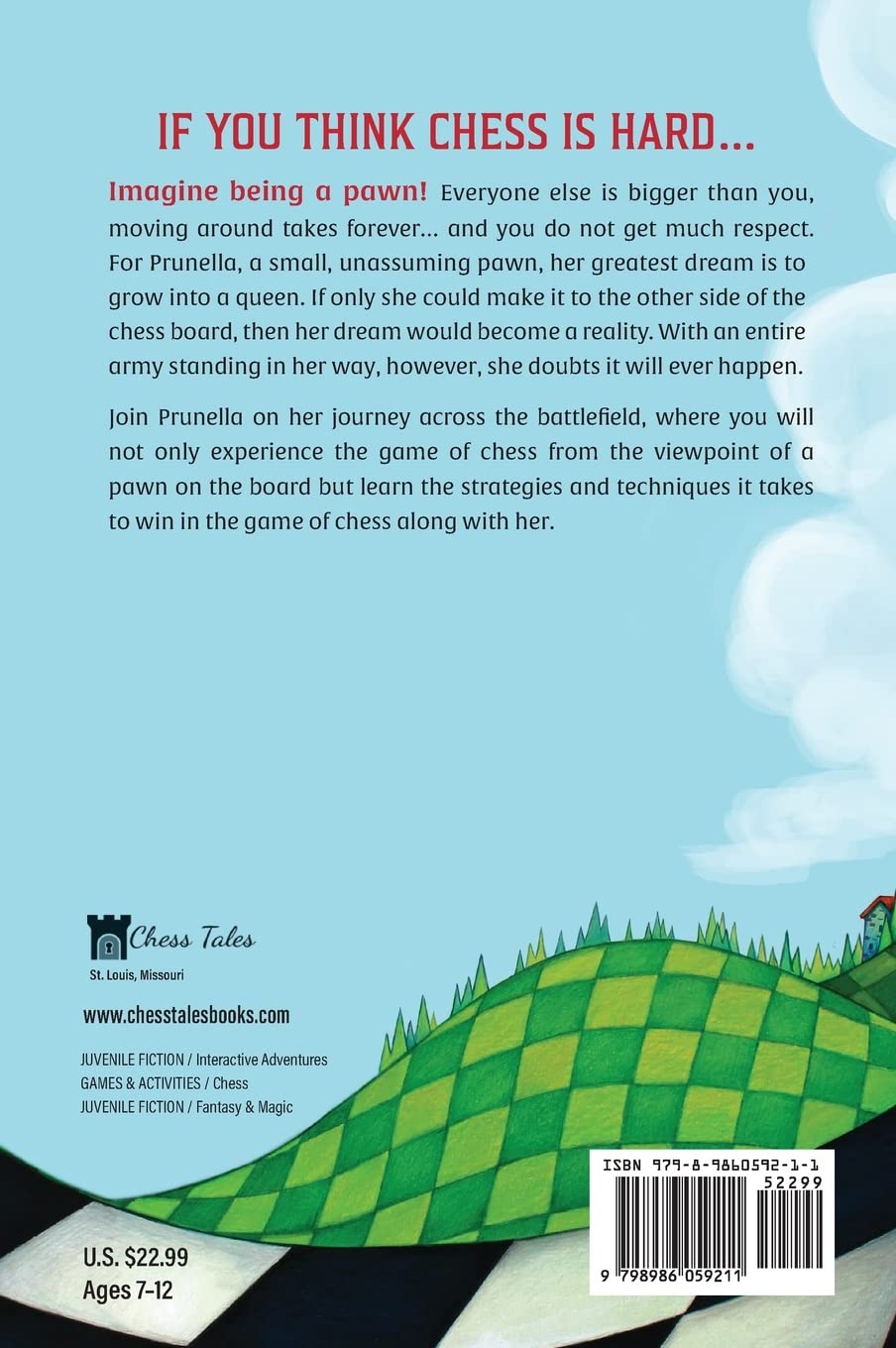

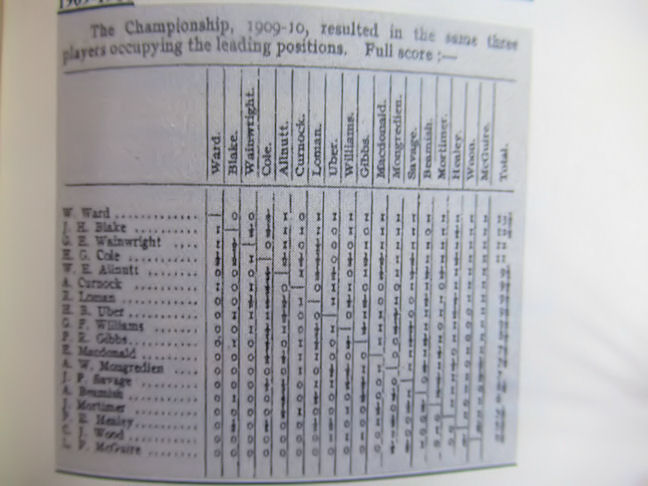

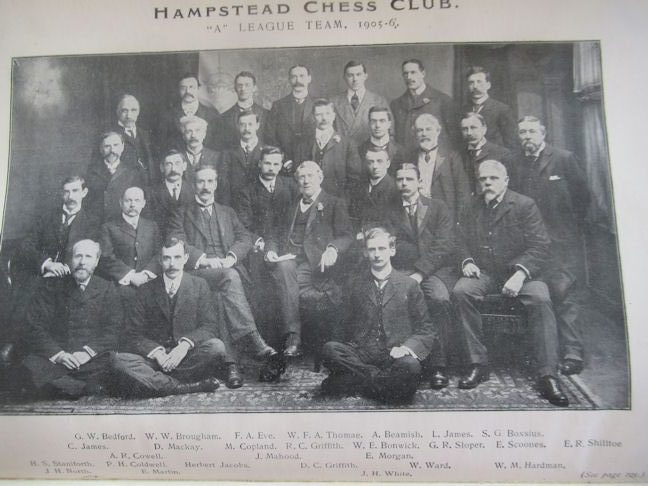

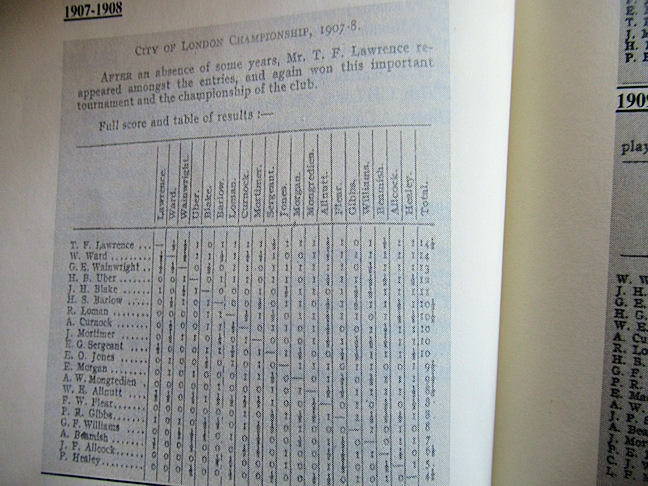

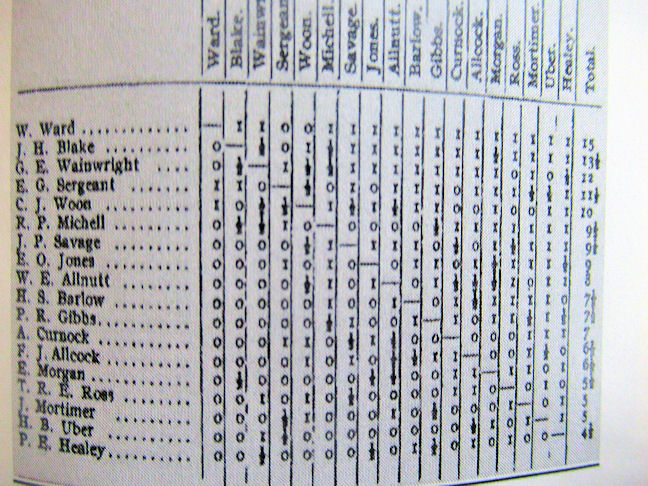

Later in the same year he returned to tournament play in the City of London Championship, taking the title for a seventh time just ahead of William Ward and George Edward Wainwright a 1-2-3 for Richmond and Twickenham chess.

He didn’t take very long to dispose of Rudolf Loman, a game which followed his game against Barry from Cambridge Springs for the first 14 moves.

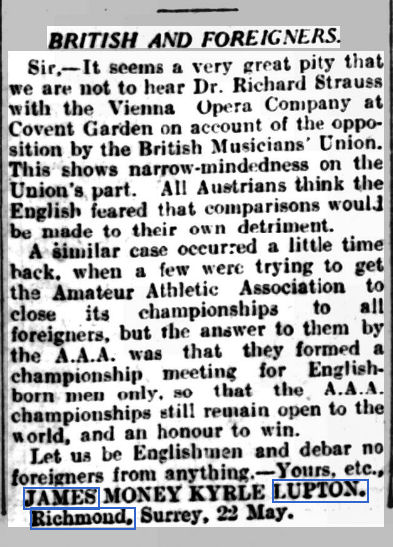

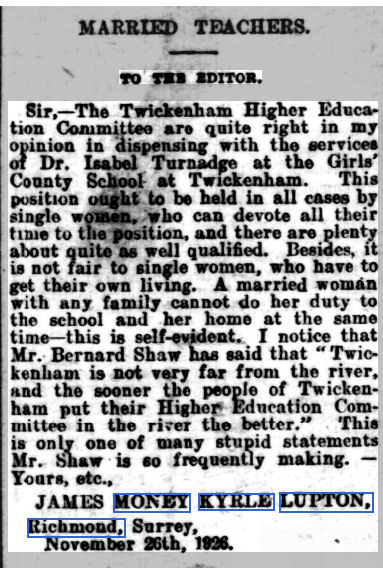

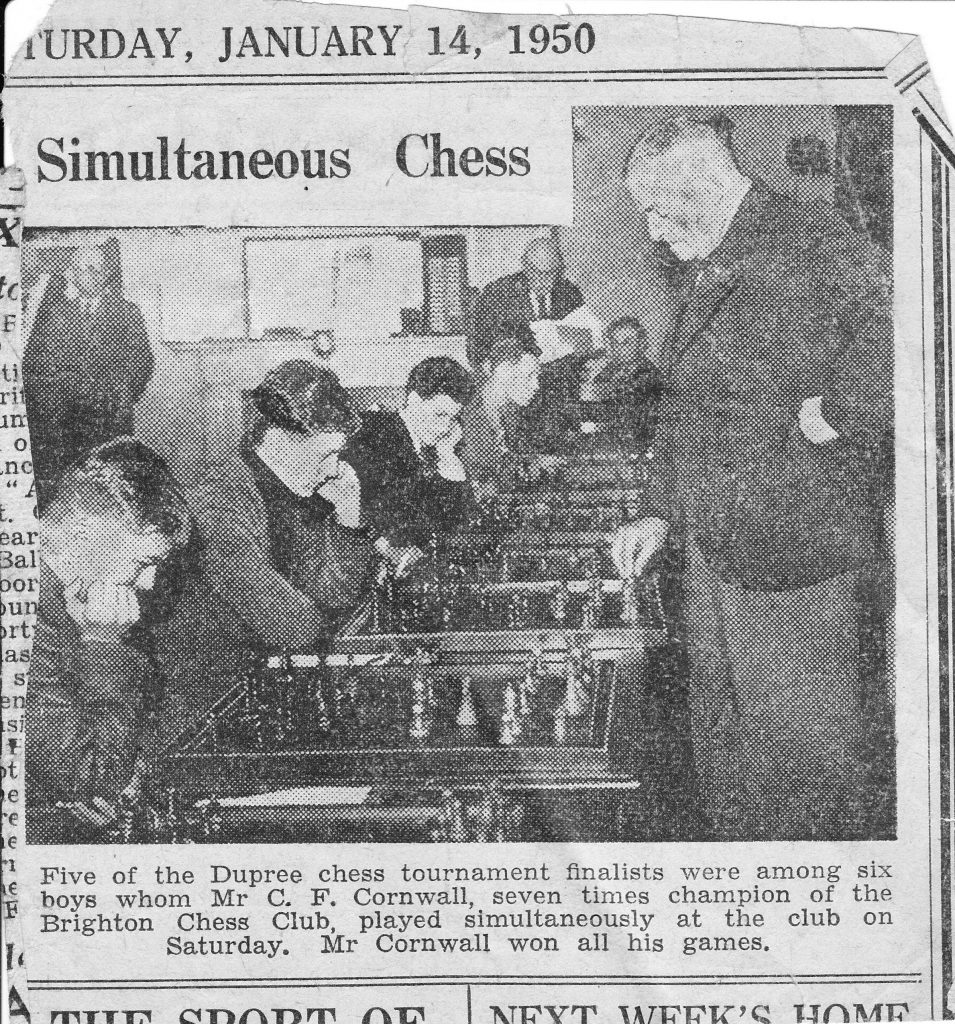

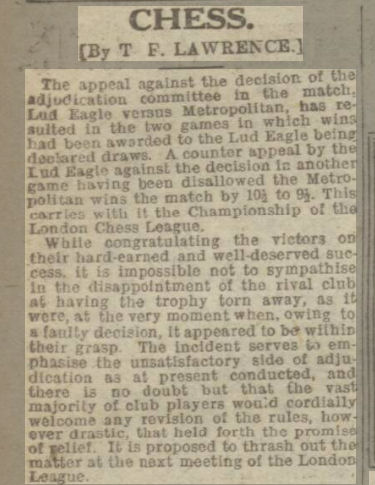

This was to be Lawrence’s last appearance in the City of London Club Championship, but he continued to play club chess, both for Ibis and for the central London club Lud-Eagle, and county chess for Surrey. He was also a popular visitor to many London clubs, giving simultaneous displays and playing consultation games.

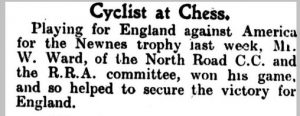

He also continued to play in the Anglo-American Cable Matches, drawing with Hermann Helms, who repeated moves in what, according to Stockfish, was a winning position, in 1908. Helms would go on to have a long and distinguished career as a chess promoter and journalist, being involved in organising the great New York tournaments in 1924 and 1927, and helping the young Bobby Fischer in 1951. Lawrence drew with his old rival John Finan Barry in 1909 and with Hodges again in 1910. In the final match, in 1911, he played a controversial game against Albert Whiting Fox, which I’ve annotated for the Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club website here. It’s well worth your attention.

This left his final record in the cable matches: played 10, no wins, six draws and four losses: perhaps slightly disappointing given his strength. Maybe the format didn’t bring out the best in him.

Meanwhile, Thomas and Mary had wasted no time at all in starting a family. A daughter, Margery (known as Peggy) was born in Mortlake just nine months after their wedding, on 28 January 1908, and baptised at St Botolph, Aldersgate on 28 March 1908. A year later, Joyce was born in Mortlake on 3 February 1909 and baptised at St Botolph on 1 May 1909. In the same year, on 23 December 1909, Ruth followed, but she was baptised on 10 April 1910 at Christ Church East Sheen, close to their family home. This is just a few yards from Sheen Mount Primary School, whose former headteacher, Jane Lawrence (no relation as far as I know) promoted chess very strongly: her pupils there included future IMs Richard Bates and Tom Hinks-Edwards.

It was at 132 Palewell Park that the census enumerator found the family in 1911: as you’d expect, Thomas, Mary and their three daughters were at home, along with Ellen Lloyd, a domestic servant, and Helen Wapshott, a nurse employed to care for the young girls.

The following year the family would be completed with the arrival of a son, named Roger Clive Lawrence, born on 12 November 1912, and baptised at Christ Church on 12 February 1913.

Earlier in 1912 the British Championships had taken place in Richmond, and the local club, of which Lawrence was now President, was involved in the organisation, but he wasn’t to be persuaded to play.

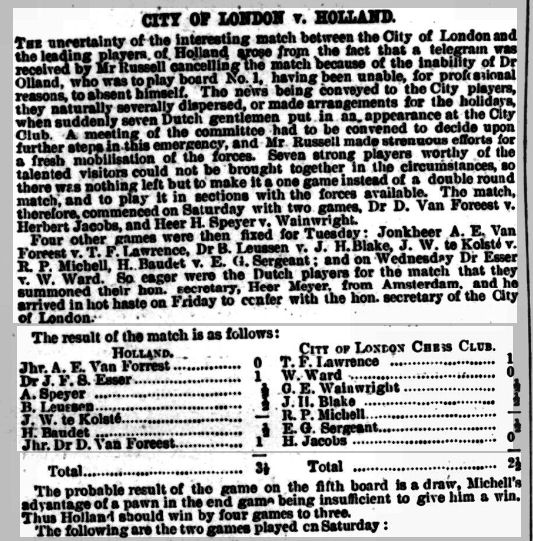

The opportunity to compete again on the international stage came knocking again the following year, when he was selected to travel to The Hague to play two matches against a Dutch team. His opponent here was Arnold van Foreest, great great grandfather of Jorden, Lucas and Machteld.

Their first game resulted in an exciting ending in which both players had advanced connected passed pawns. Lawrence eventually came out on top, as you can see here.

He scored a quicker win in the return encounter when his opponent miscalculated the tactics on the open e-file.

Club chess was curtailed during the war, and, with a growing family, Thomas Francis Lawrence had other demands on his time. He did, however, continue writing in The People up to January 1916. Here, he proposed the abolition of adjudications.

More than a century on, we haven’t progressed very far. Even today, the January 2022 Rules of Play on the London League website still allows for adjudications. Lawrence must be turning in his grave.

He still seems to have been playing occasional club chess: in December 1919 Ibis welcomed a visiting team from Hastings, with Lawrence drawing with MCO co-author Richard Clewin Griffith on top board.

By 1921 the family had moved just round the corner, to 92 East Sheen Avenue, backing onto the house across the road from their previous address. Thomas was by now a Principal Clerk with the Prudential Assurance Company Limited, Mary and their four children were also at home, as was Helen Wapshott, a nurse a decade ago but now a general domestic servant.

Lawrence retained his interest in the game for the rest of his life. He still played occasionally for Ibis, in 1925 losing rather horribly on top board against George Marshall Norman in one of the regular Hastings v Ibis matches.

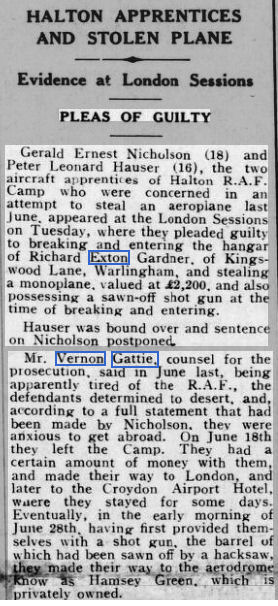

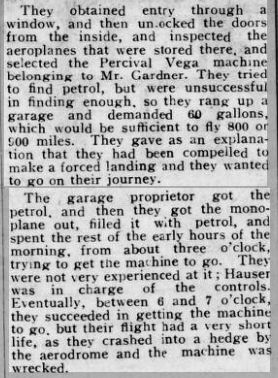

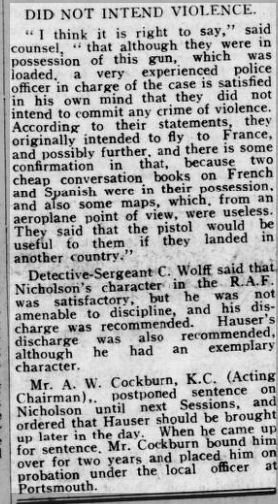

At some point in the 1930s Thomas retired from his job with the Prudential and retired to Comp Corner Cottage, Wrotham, Kent (between Sevenoaks and Maidstone), now a Grade 2 Listed Building, where, in 1939 he was living with Mary, Ruth and two of Mary’s unmarried sisters, Louisa and Charlotte, the latter of whom was employed as a schoolmistress teaching domestic subjects.

His great-niece Jill recalled visiting him at Comp Corner. There were always huge jigsaw puzzles on a huge table in the house in Comp Corner, Wrotham, Kent. Tom was very clever, wealthy, occupation unknown, believed to have been South-East chess champion. Well, he was seven times champion of the City of London Chess Club, which was very much the same thing, as most of the strongest players in the South East took part.

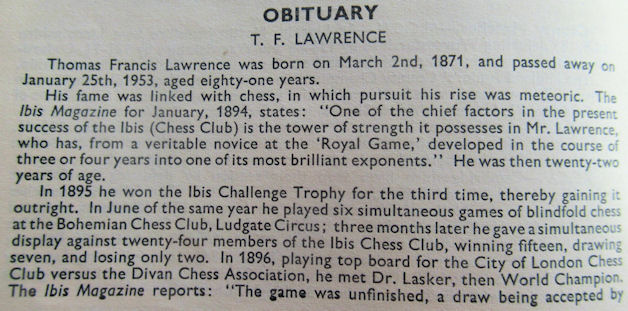

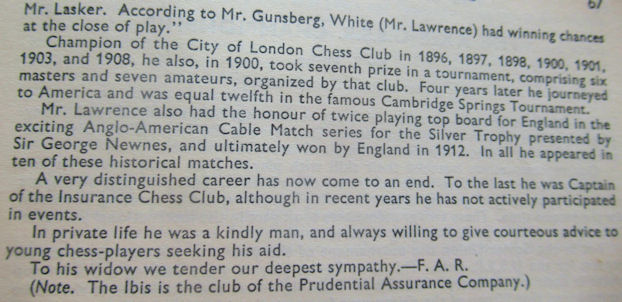

The family finally moved to Storrington, Sussex in about 1950, where he died on 25 January 1953 at the age of 81. Here’s his obituary from the BCM: I presume FAR was Frank Rhoden.

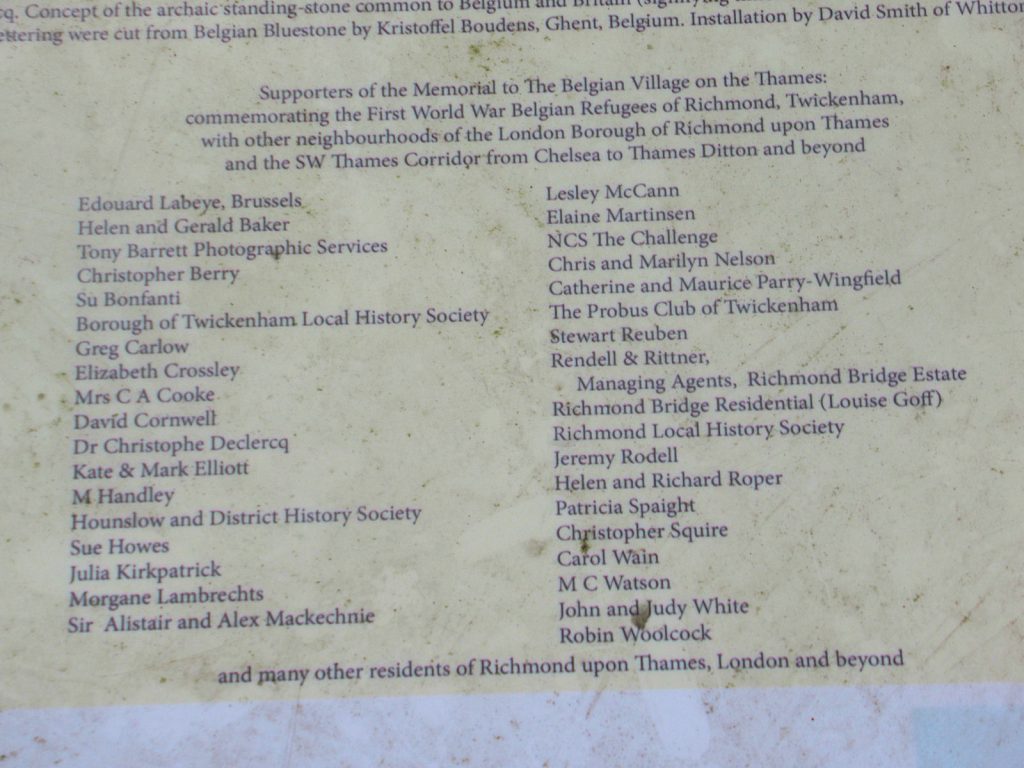

Several mysteries remain. After a recent post on the English Chess Forum, Sussex chess historian Brian Denman contacted me with this message, repeated here with his permission.

The following story will probably have not surfaced for over fifty years. The Worthing Gazette of 27.7.1966, which had as its chess columnist Leslie A Head, reported that thirteen years previously the Worthing CC had in its possession one of the most famous trophies in the history of British chess. The Ibis Challenge Trophy was once the championship trophy of the City of London CC and was won outright by T F Lawrence in 1898. About sixteen or seventeen years ago Lawrence had come to live in Storrington. He invited David Armstrong and the columnist to play him an occasional game. On one of these visits he showed the trophy, which consisted of a set of large ivory chessmen and board. The next time that the columnist heard about the trophy was in January 1966, when a reader, who insisted on remaining anonymous, informed him that the trophy had been presented to the club by his widow. The club minutes in fact recorded that in March 1953 the trophy had been presented to the club by the widow on condition that, if the club parted with it, it should be to a person interested in chess. At that time the committee could not decide how to use the gift and the matter was left in abeyance. Head commented that the club might have held a Lawrence Memorial Tournament or displayed the trophy at Annual General Meetings. In a follow-up article in the Worthing Gazette of 10.8.1966 Head mentions that Eric Chettle, secretary of Worthing CC from 1955-59, remembers the trophy being in the club’s cupboard. The club wrote to Jacques and were told that the set would be worth £60, though the firm no longer made them. Mr Chettle said that he had sold it to a Chichester player for £18 or £20. The columnist commented that it was very sad that this priceless and historic trophy had been hidden away in a cupboard unrecognised and unappreciated until it was sold for a few paltry pounds. He asks why there was such secrecy over the sale. The Worthing Herald of 3.10.1958 mentions that a fall in the club’s membership had caused anxiety and the set had been sold for £20 to ease the club’s balance. One wonders if the set still exists.

There seems to be some confusion with regard to this trophy. I suspect that the BCF obituary was incorrect: my guess is that the Ibis Trophy was originally the Mocatta Trophy, which Lawrence won in 1898 for his third successive victory in the City of London Club Championship. He then donated it to the Ibis Chess Club, whereupon its name was changed. When they no longer had use for it, it returned to Lawrence’s possession, and was then passed onto Worthing Chess Club by his widow after his death in 1953. Anyway, if anyone has any idea what happened to it after it was sold to the ‘Chichester player’, do please get in touch.

There are two other mysteries as well: I still have no idea who exactly his father Henry Lawrence was. I’m also interested in what happened to his brother. He had three Christian names: Henry Arthur Edward, although he seemed to vary their order, so it should be relatively easy to track him down. We can pick up his birth in Velsen in 1873, and see him living with his mother in London in 1881, 1891 and 1901, up to her death in 1903, but after that the trail goes dead. I can find no marriage or death records with those three names in any order, nor any information on online family trees. Again, if you can help with either Henry, father or son, I’d love to hear from you.

What should we make of Thomas Francis Lawrence as a chess player? He was clearly very talented but his games don’t make a particularly strong impression today. With more ambition and perhaps a wider opening repertoire (I don’t think his predilection with the Spanish Four Knights helped very much) he might have reached grandmaster level, but he didn’t play a lot at the top level and seemed to have had other priorities – work and family – in his life. Nevertheless, wins against Pillsbury and Blackburne and draws with Lasker and Chigorin are not to be sniffed at.

More than that, he comes across as a genuinely nice and modest person. Returning to the BCM obituary: ‘a kindly man, and always willing to give courteous advice to young chess-players seeking his aid’. A fine and fitting epitaph, I think. I’m very proud that Thomas Francis Lawrence was one of my predecessors as President of Richmond (& Twickenham) Chess Club.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

Google Maps

chessgames.com

MegaBase

The City of London Chess Club Championship (Roger Leslie Paige)

British Chess Literature to 1914 (Tim Harding)

British Chess Magazine 1953

English Chess Forum

Chess Notes (Edward Winter)

BritBase

Gerard Killoran

Brian Denman

Hastings Chess Club website

Cambridge Springs 1904 website