After four years, ending in 2014, of working with the Bulgarian Grandmaster, Veselin Topalov, the second (“a Second generally has to work at night, often all night”) to the former FIDE World Champion speaks of his duties, preparation and with colour (“He fought like a lion for 71 moves”). It is a tale of dedication and loyalty to a seemingly fearsome character. (Presumably this could not have been written whilst the author, who is also the Managing Editor of Thinkers series, was under contract?!)

Chapters: A World Apart. The Start of Our Co-operation. Learning the Job. Zug More Success! Tough Times in Thessalonika. Rollercoaster in Beijing! Preparing for the Candidates. The Candidates Tournament. A Few Novelties More. Exercises 24 positions and Solutions.

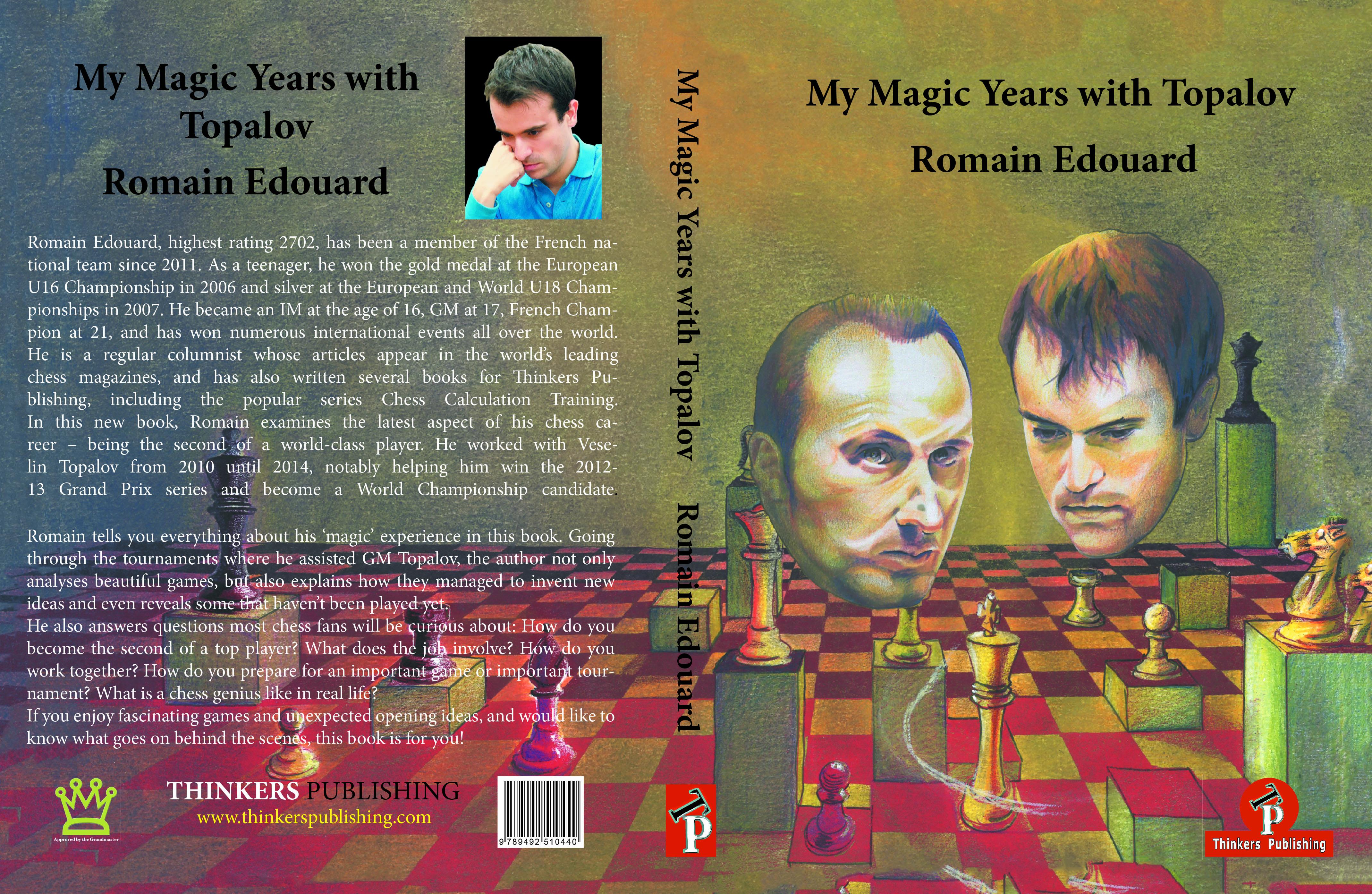

Many annotated games, mostly recent, no Rabars but ratings quoted. Use of smaller diagrams in notes (good!). A few cartoons and 7 crosstables. Very artistic colour cover. No index.

Digestible and thorough and, happily, honest. The author has been a French grandmaster for the last decade.

James Pratt, Basingstoke, April 2019

Book Details:

- Paperback: 310 pages

- Publisher: Thinkers Publishing 28th April 2019

- Language: English

- ISBN: 9492510448

- ISBN-13: 978-9492510440

- Product Dimensions: 17 x 2 x 23.4 cm

- 31 black and white photographs

Official web site of http://www.thinkerspublishing.com