The Immortal Games of Capablanca: Fred Reinfeld

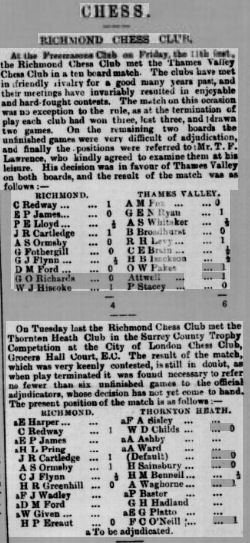

From the publisher:

“We are pleased to release another book in the Fred Reinfeld Chess Classics series. The Immortal Games of Capablanca was – and continues to be – one of Reinfeld’s most popular books. A detailed biography of the third world chess champion introduces the 113 games. They are presented chronologically, with clear and instructive annotations.

This 21st century edition has been revised and reformatted to meet the expectations of the modern chessplayer. This includes:

(a) The original English descriptive notation has been converted to modern figurine algebraic notation;

(b) Over 200(!) diagrams have added, along with more than a dozen archival photos; and

(c) The Index of Openings now has ECO codes.

Reinfeld’s annotations were also cross-checked by Stockfish 14, one of the most powerful engines available. When Stockfish had a different, meaningful evaluation from that of Reinfeld’s, the engine’s suggestion is indicated by “S14:” followed by the specific line.

As in our other “21st Century Editions,” and with the exception of the occasional supplement by Stockfish, Reinfeld’s original text has been preserved.

Follow the life and games of the brilliant Cuban world champion in Reinfelds’s timeless classic The Immortal Games of Capablanca.”

End of blurb…

According to Wikipedia:

“Fred Reinfeld (January 27, 1910 – May 29, 1964) was an American writer on chess and many other subjects. He was also a strong chess master, often among the top ten American players from the early 1930s to the early 1940s, as well as a college chess instructor.”

In July 2019 Richard James reviewed Fred Reinfeld: The Man Who Taught America Chess, with 282 Games and perhaps you might like to read this to get a better feel for FRs legacy.

Russell Enterprises (via New In Chess) with this new edition have, to date, added a total of eight titles to their Fred Reinfeld Classic Series: the more the merrier!

Over the years many have looked down their noses at publications from Reinfeld, Chernev, Schiller and others but if we are completely honest then Reinfeld and Chernev have brought a huge amount to the chess buying public and many have found much benefit from their publications.

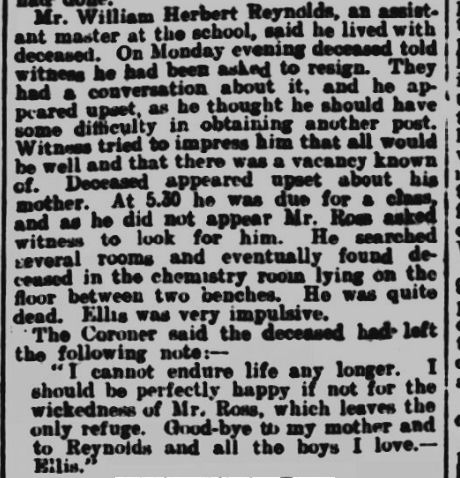

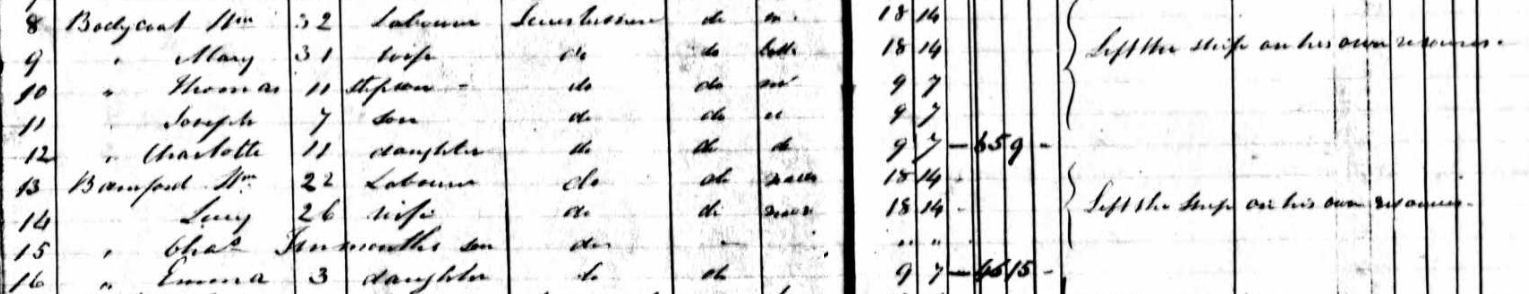

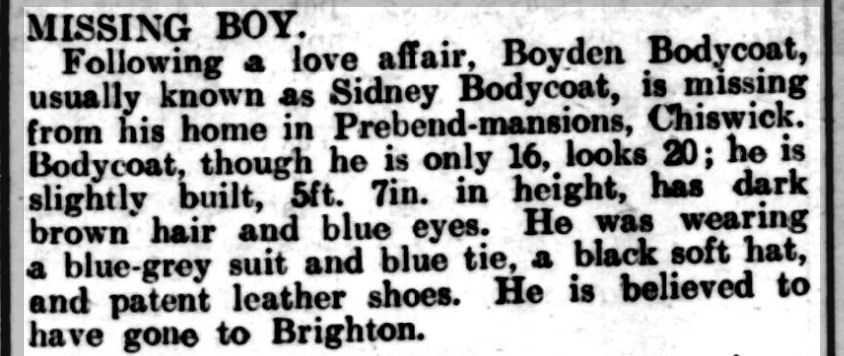

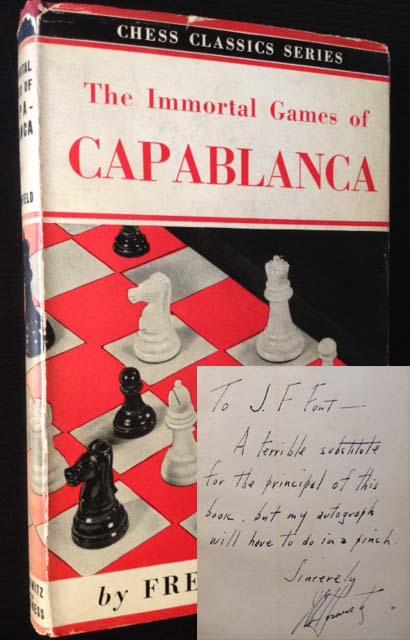

The Immortal Games of Capablanca by Russell Enterprises is (to use a modern phrase) a “re-imagining” of a timeless classic. Most of us reading this review would have almost certainly had one of the previous versions. The first edition dates from 1942 and, interestingly, the copyright lies with Beatrice Reinfeld rather than Fred, himself. Published by Horowitz and Harkness, New York here is an original first edition copy from the collection of Jose Font:

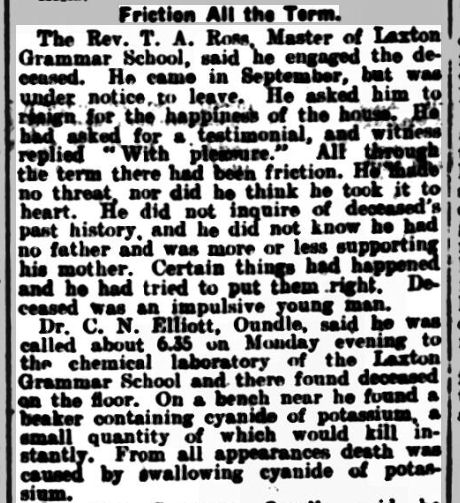

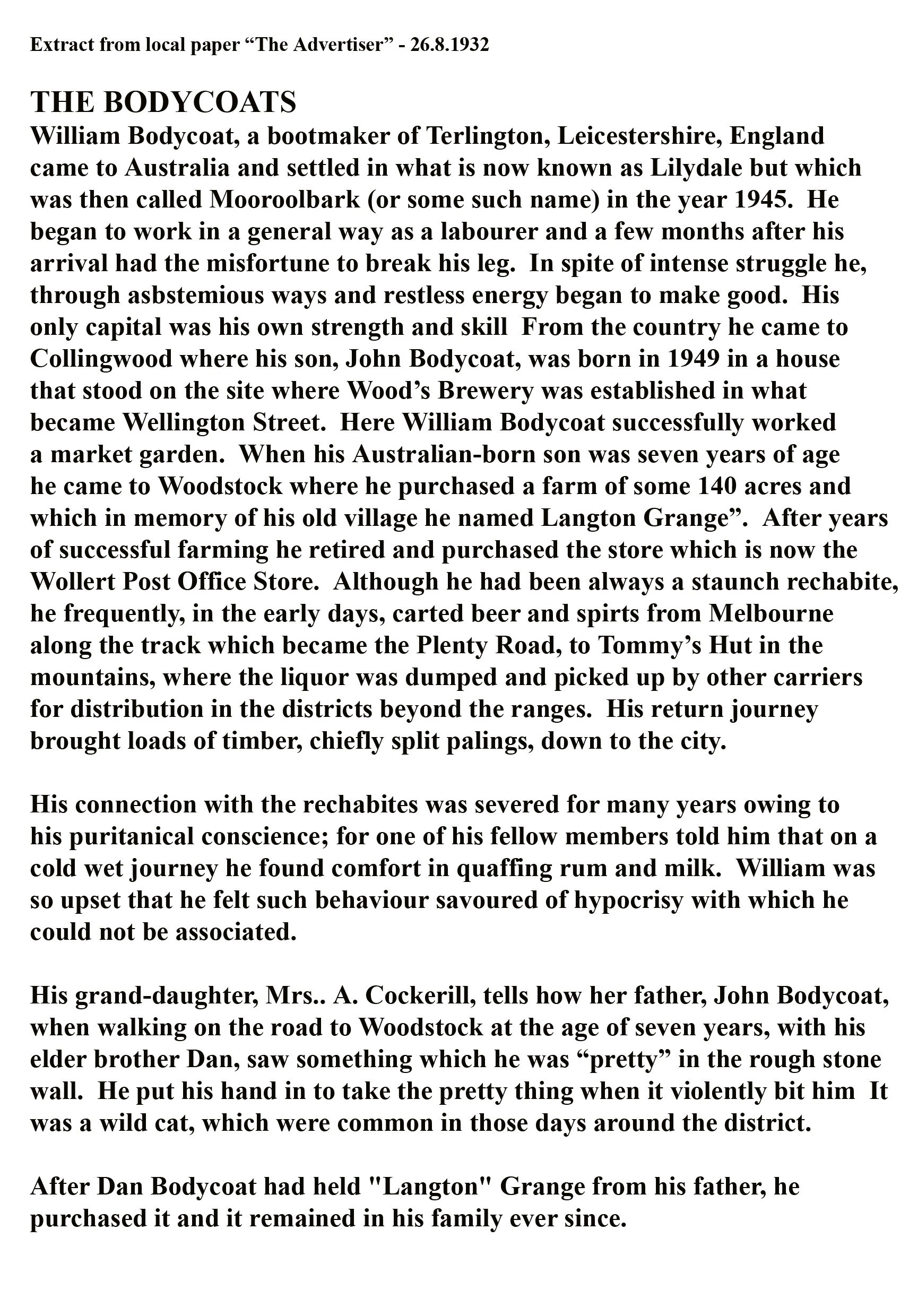

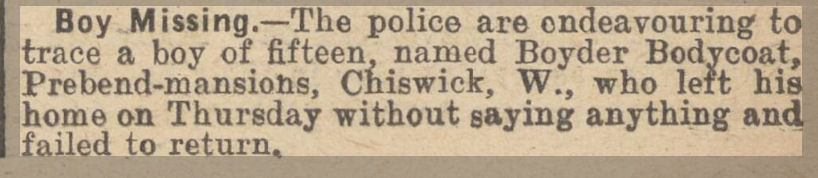

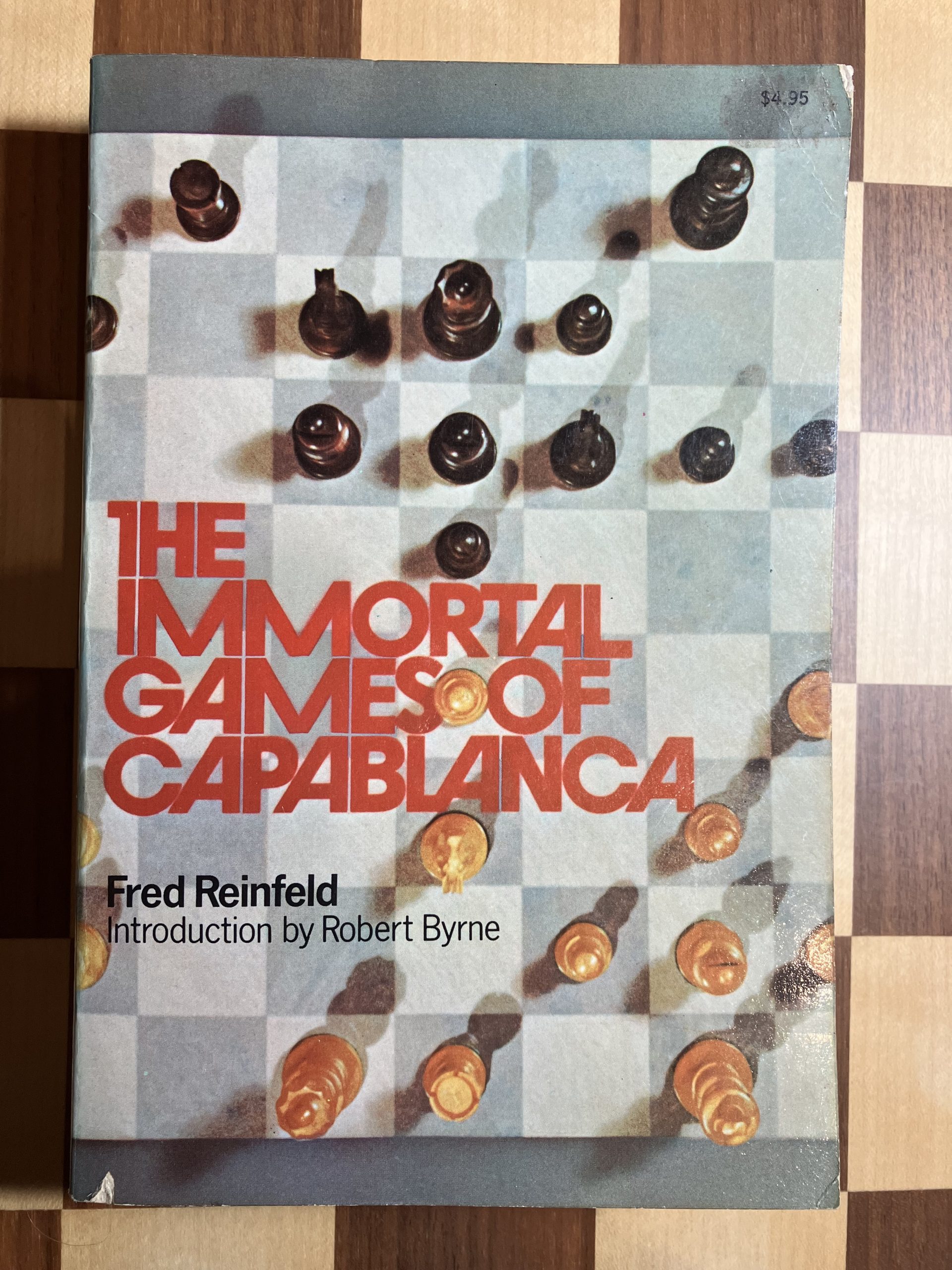

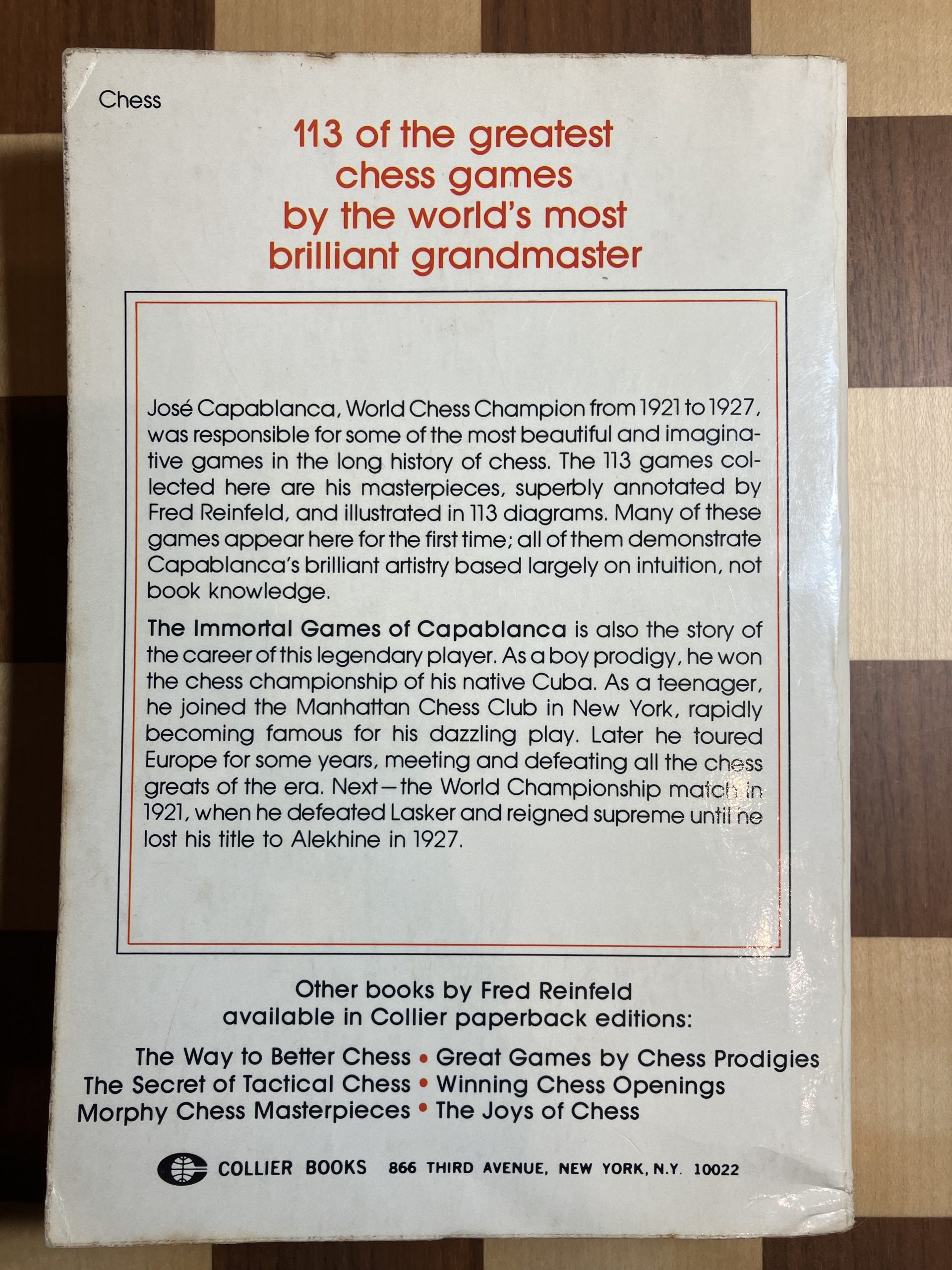

Betts (Chess: An Annotated Bibliography of Works Published, 1850-1968) informs us that this very edition was re-issued in 1953 by the same publisher. In 1974, Collier Books (A Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. New York) brought out their own edition and added an Introduction by Robert Byrne, Chess Editor of The New York Times. This had the following appearance front and rear:

and, for the sake of completeness, and because it is worth reading, here is the Introduction from Robert Byrne:

Introduction

I joined the Manhattan Chess Club a year or so after Capablanca’s death, and the afterglow of the great Cuban’s presence still filled his favourite haunts. There was an old white-haired patzer, Richard Warburg, who would collar me, my brother Donald, and several other young high school players to tell us the “compliment” Capa had once paid him. What Capa had said was, “Warburg, nobody plays the Rinky-Dink the way you do!” So overcome with pride and delight was Warburg that the great man had deigned to remark on his play that he never stopped to think why Capa had dubbed his Accelerated Dragon Variation the “Rinky-Dink.” Needless to say, the ironic joshing of Capablanca’s remark was totally lost on him.

Moreover, it would not have mattered, for Capablanca was so idolized that it was deemed a privilege to breathe the same air he did. Not only did his fans feel that way about him, but the man from whom he won the world championship, Emanuel Lasker, said of him, “I have known many chess players, but only one chess genius.” Capablanca’s successor, Alexander Alekhine, also termed him “a very great genius whose like we shall never see again.”

What lent Capablanca the glamour that was denied to his fellow champions of the game was the incredible speed of his play. Hard work at the board, consuming the full two and one half hours for forty moves, was unknown to him at the peak of his career. Brilliant strategic plans, marvellous com binational possibilities, scintillating turns in the play came tumbling out of him in response to his extraordinarily quick sight of the configuration before him.

He did not consider what he achieved as coming under the head of thinking, scandalizing his colleagues by insisting that chess was not an intellectual game. For him it was nothing remotely resembling problem solving, but rather flashes of intuition in which he grasped the essential pattern governing each individual position. That is why he looked upon chess playing as an aesthetic activity.

Quite obviously, no greater natural player ever lived. At the age of four, Capablanca learned the moves by watching his father play and, years later, he declared that he had never bothered to study the game. Of course, growing up in the fertile chess climate of Havana and later New York, he honed himself on very strong opposition. Watching the games of his competitors could hardly have failed to serve as an education in itself.

In chess style, Capablanca was the master par excellence of reduction, stripping positions down to the bare backbone by exchanging off all irrelevant material. In what were for others

positions of unfathomable complexity, he could, with uncanny lucidity, expose the genuinely dominant but often hidden theme that dictated the strategy to be pursued.

It is this astonishing clarity in Capablanca’s conceptions that makes his games a gold mine for the aspiring student. The elements of chess strategy can all be seen here purged of the confusion introduced by side issues. The late Fred Reinfeld has made an excellent selection of 113 Capablanca games which give a rounded picture of the scope and invention of Cuba’s greatest genius. These are the wonderful performances that have so heavily shaped the play of current world champion Bobby Fischer, Capablanca’s spiritual descendant.

One of my favourites, which I have replayed many times, is game 6, from Capablanca’s match with Frank Marshall (see page 39 ). It is not too much to say that this is the indispensable stem game for the understanding of how White develops a kingside attack in the Ruy Lopez. Another lesson in the Ruy Lopez, this time in the exchange variation by transposition, is given by game 17 against David Janowski (see page 83). Capablanca’s handling of the pawn structure and his fine rook play in the ending beautifully illuminate a formation reintroduced into current practice by Bobby Fischer.

In the realm of bishops-of-opposite-colour play, the drawing chances of the defence can only be defeated by the kind of positional mastery Capablanca evinces in game 2L against Richard Teichmann (see page 97 ) and in game 25 against Aron Nimzovich (see page 111). Capablanca’s terrifically coolheaded defensive play shows up in his defeat of Frank Marshall’s anti-Ruy Lopez gambit in game 36 (see page 157), which the American champion kept under wraps for eight years to spring on him. I could go on and on, but, if I must limit myself to just one more, Capablanca’s best-played-prize-winning Caro-Kann Defense in game 63 against Aron Nimzovich (see page 276) would be my choice. It is a wonderfully instructive masterpiece of infiltration tactics to undermine a passive position and score with Zugzwang.

Fred Reinfeld’s annotations are clear and schematic and give a dramatic portrayal of these epic battles. Fred, the epitome of the hero-worshipper, is a little too harsh in fastening on the very human foibles that brought about Capablanca’s loss of the world championship to Alekhine. With the ease of success Capablanca enjoyed, it was all but impossible for him to have taken Alekhine’s challenge seriously, especially since Capablanca had a 6-O record against him going into the match. No one could have guessed the fanatic zeal that Alekhine put into his preparation for the struggle.

Moreover, the last word on Capablanca’s enormous capacity can be gleaned from Alekhine’s behaviour. He sought lesser opponents rather than give the awesome genius a return match.

-Robert Byrne”

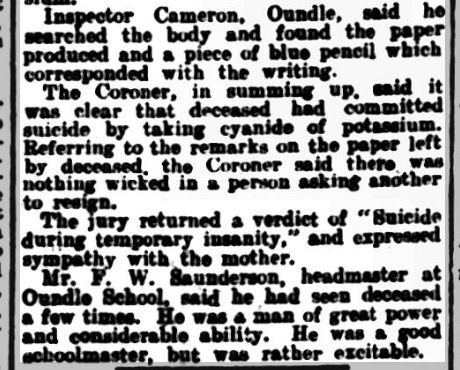

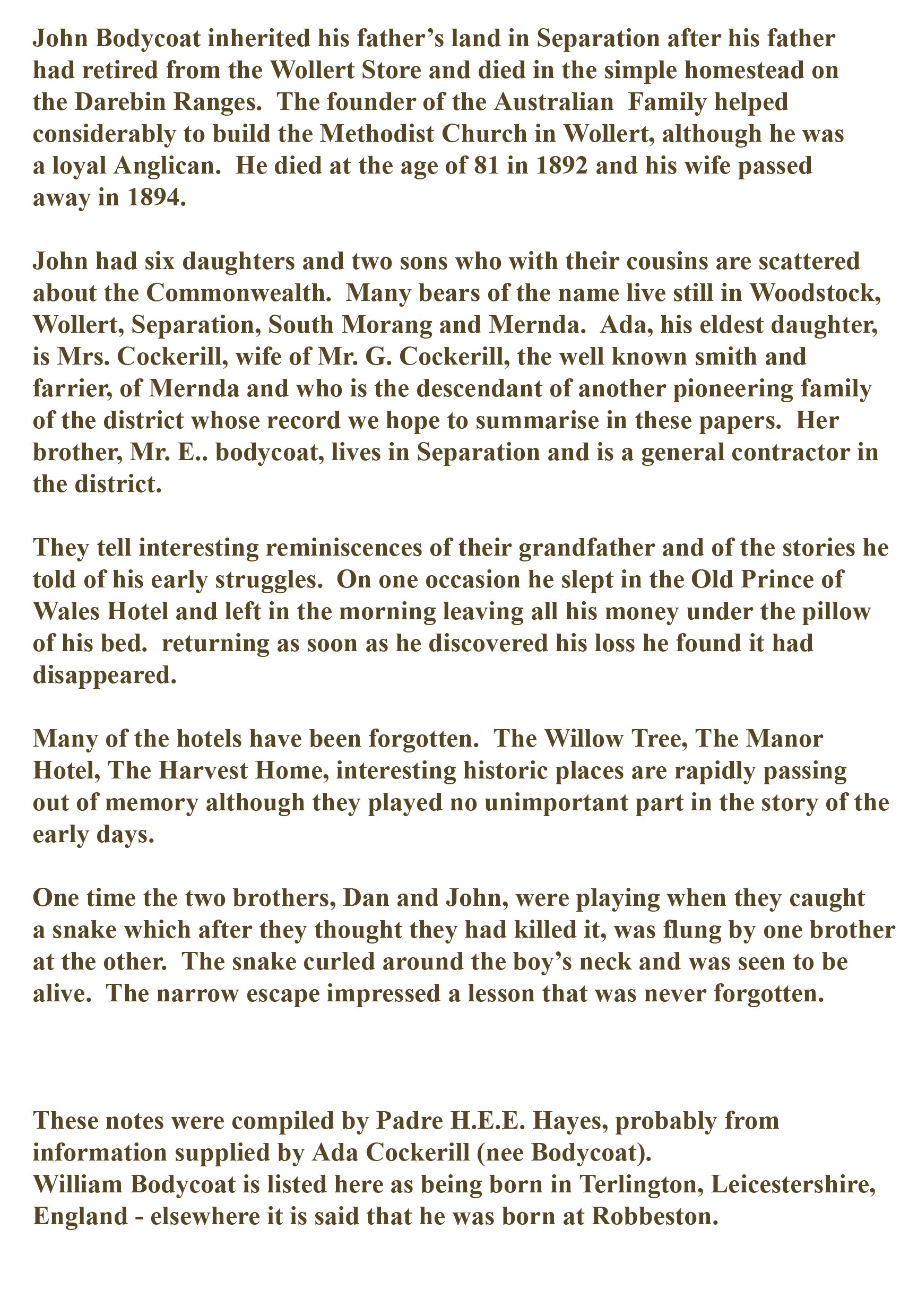

In 1990 Dover did their usual “reprint” thing and re-issued the Horowitz and Harkness, New York, 1942 version with this cover:

and in 2011 Sam Sloan put on his anti-copyright Ye-Ha! cowboy spurs and re-issued his version with the original 1942 cover.

So, in 2022, what do we have that is new in this 21st century edition?

Firstly, we have FAN or figurine algebraic notation which should help to bring in those for whom English Descriptive is old hat (their words not ours).

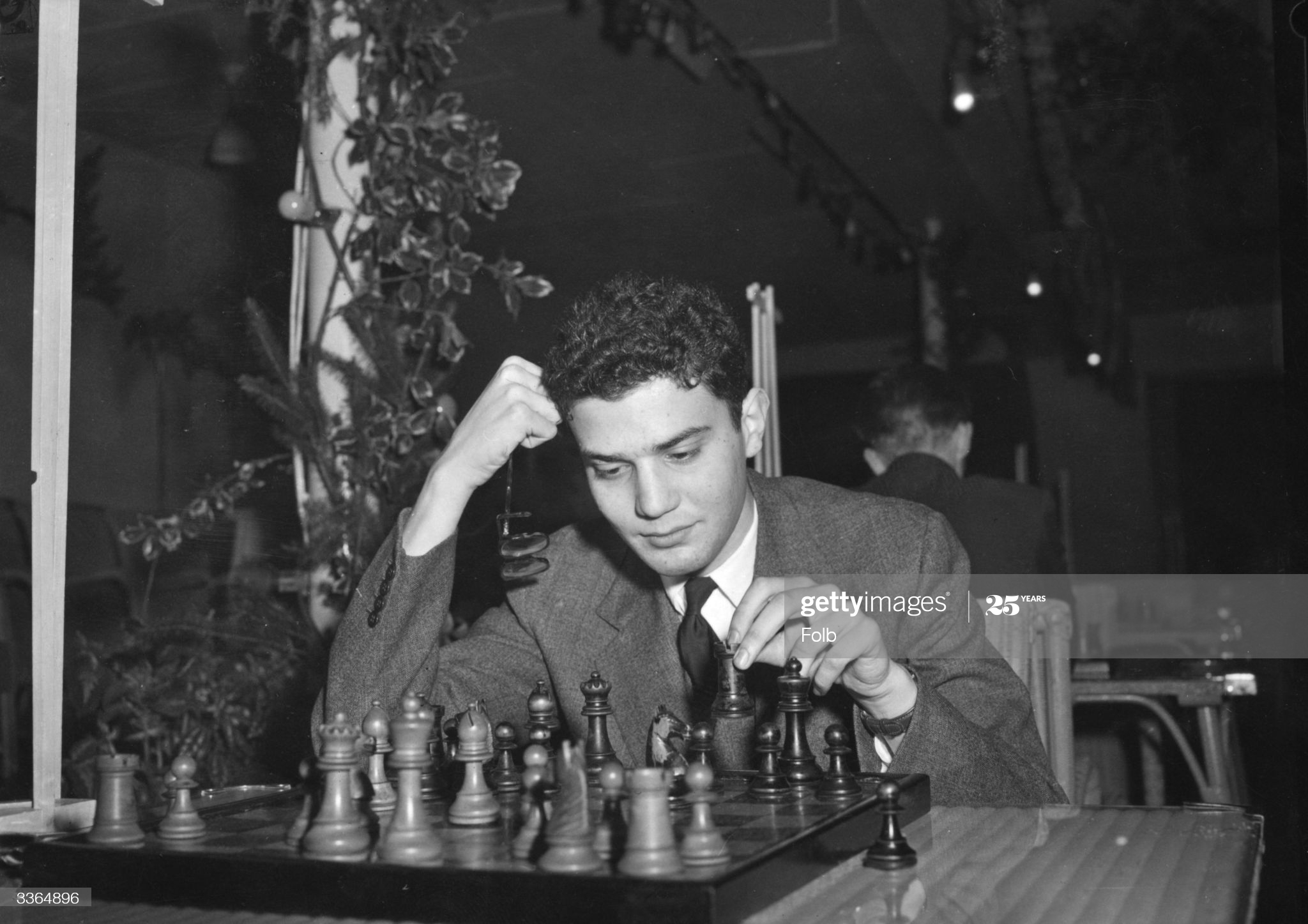

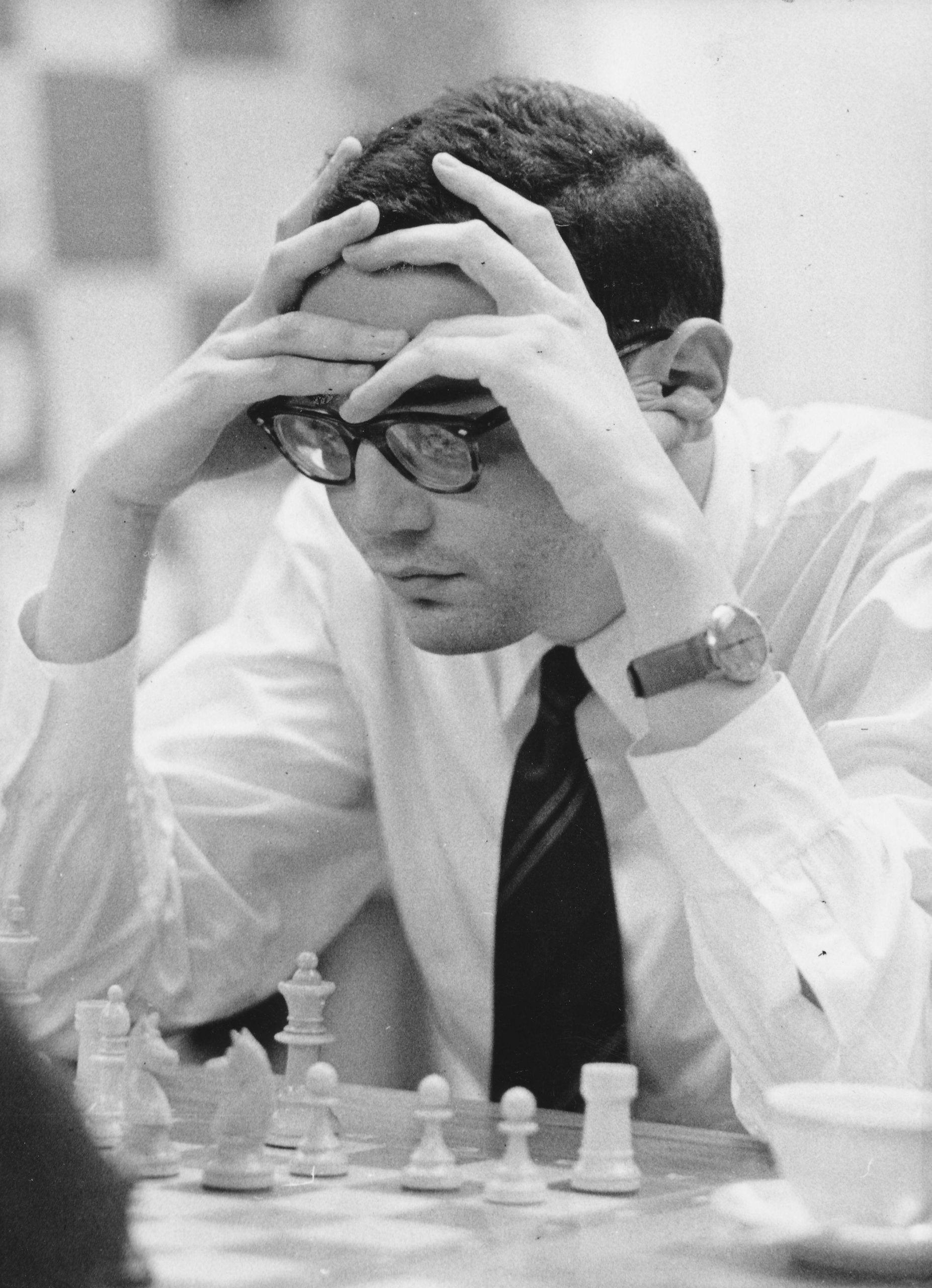

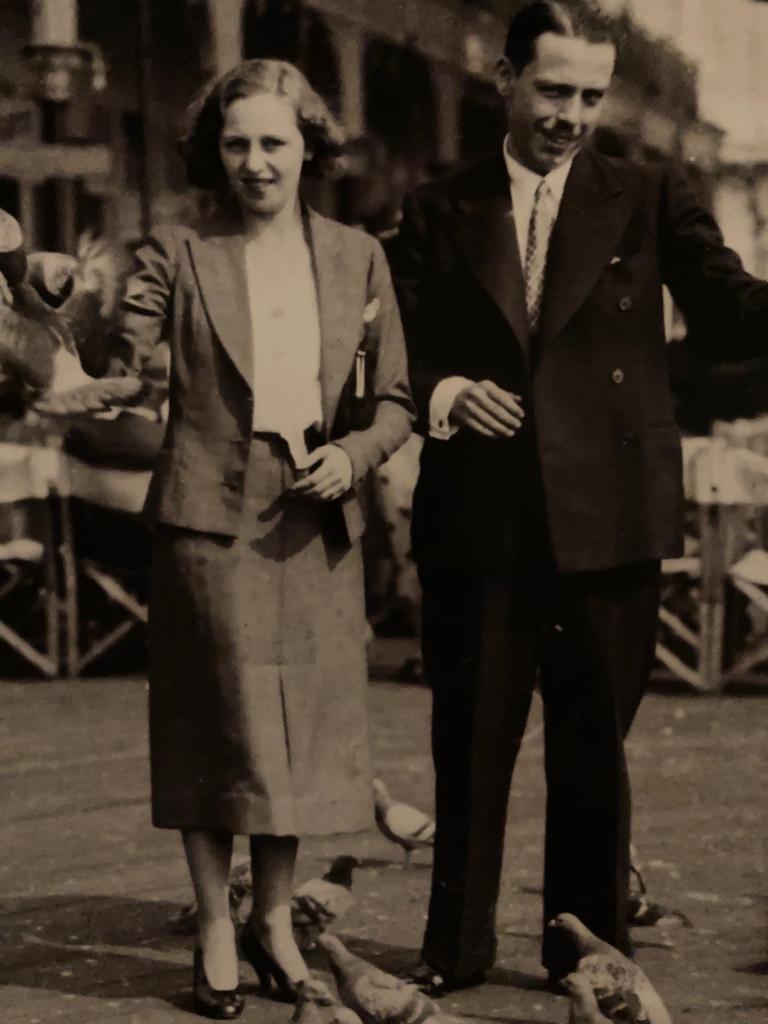

Secondly, thirteen photographs of of Capa and his opponents liven up the pages that once contained a single image of Capa giving a simultaneous display at the Imperial Chess Club in London, 1911. Printing quality could have been improved but welcome they are nonetheless.

The format has transitioned from the old style single column with diagrams few and far between to a double column format with a liberal sprinkling of diagrams of greater printed clarity than the originals. Each game has been allocated an ECO code (or Rabar Index for our more mature readers). Indeed, the font is a little smaller than it was in 1942 but quite readable all the same.

The authors pithy annotation style has been retained for the modern student to enjoy and engine worshippers (“I cannot read a chess book that has not been engine checked”) are acknowledged using supplemental comments indicated by a Stockfish (S14) label.

We carried out a detailed edition comparison with the Collier edition and found some subtle differences. As noted previously the Robert Byrne Introduction is not present but then again, it wasn’t in the original. Game 2a, Corzo-Capablanca is now Game 3 and the comment “This game discovered just as the book was going to press” is no longer present.

Capablanca-Voight, Philadelphia, 1910 is labelled as a Team Match between Manhattan CC and Franklin CC in 1942 and in 2022 as a simultaneous display game. Both Megabase 2023 and Chessgames.com concur with the recent verdict: any Capa scholars (EGW) out there with definitive knowledge?

Game 15 is now identified as Capablanca – Bacu Arus from a blindfold simul whereas Black was listed simply as “Amateur” in the original.

Through out this fresh, new edition there are subtle additions of detail together with corrections to the original which are to be admired.

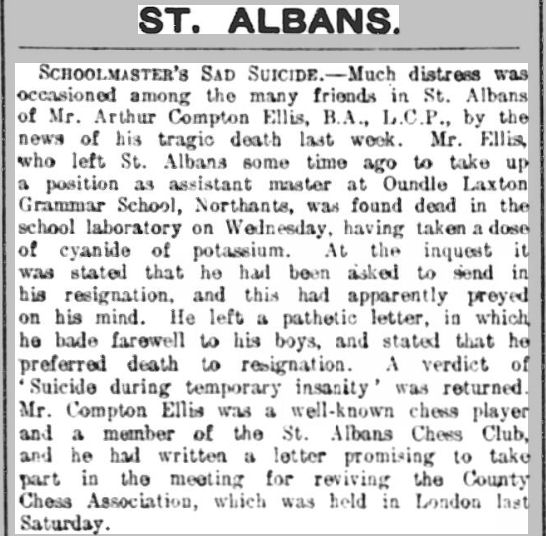

The Stockfish (S14) comments are sparse and unobtrusive but of value. For example, from Capablanca- Janowski we have reproduced the comments to Black’s 24th move only:

In summary it was an absolute pleasure to be re-united with this timeless classic and Russell Enterprises are to be congratulated on producing this fresh new edition with added value.

John Upham, Cove, Hampshire, 2nd March 2023

Book Details :

-

- Softcover : 256 pages

- Publisher: Russell Enterprises (September 12, 2022)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1949859274

- ISBN-13: 978-1949859461

- Product Dimensions: 15.24 x 1.27 x 22.86 cm

Official web site of Russell Enterprises

The Immortal Games of Capablanca Reinfeld, Fred Reinfeld, Russell Enterprises, Hanon Russell,

September 12, 2022, ISBN:

9781949859461

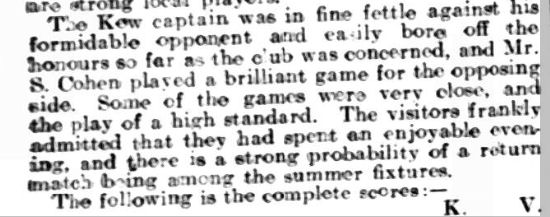

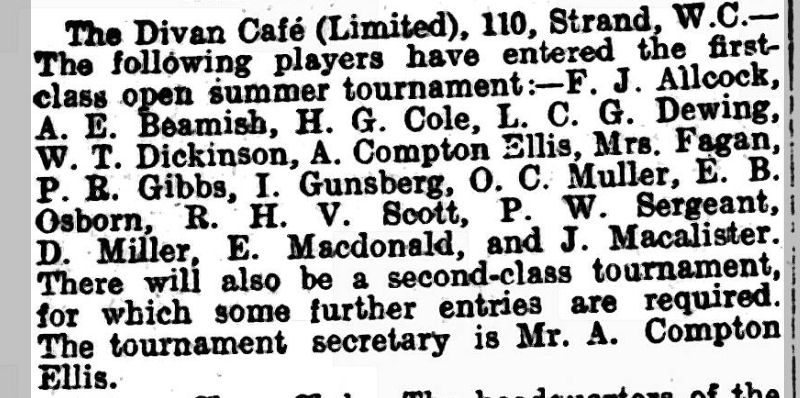

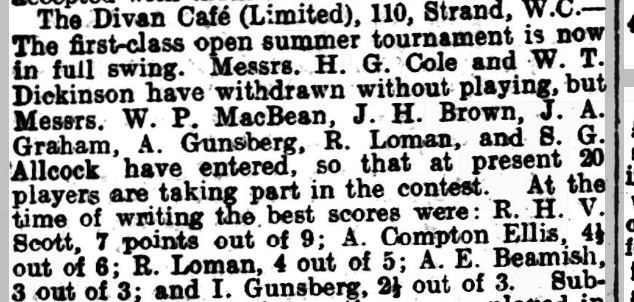

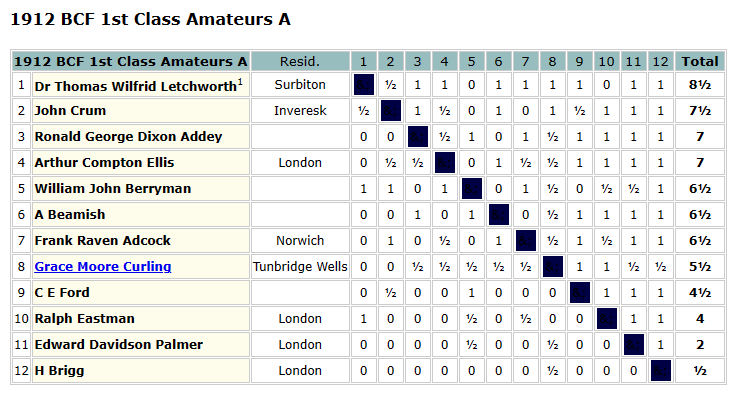

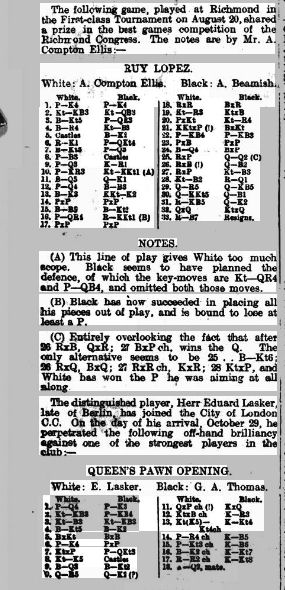

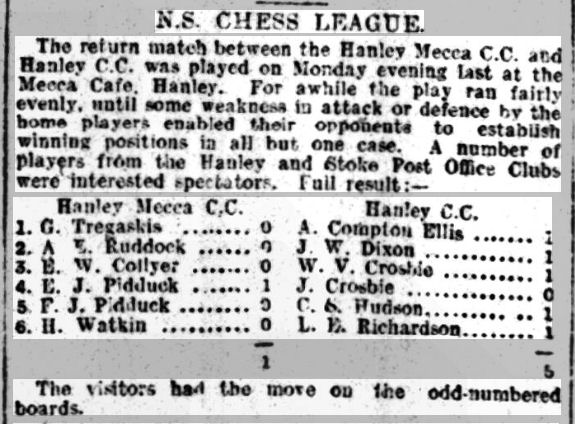

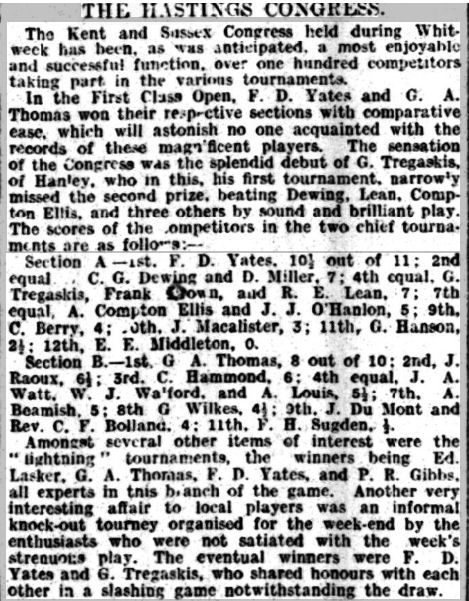

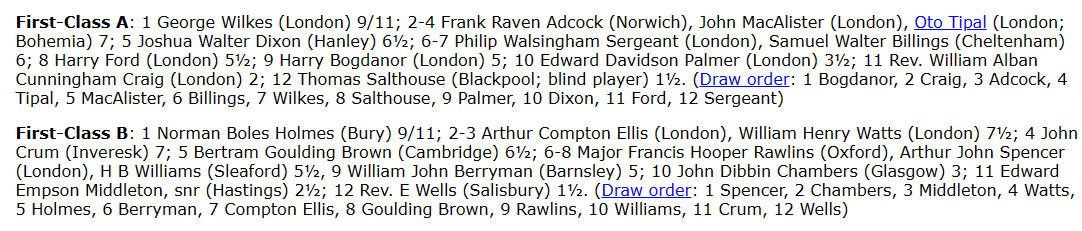

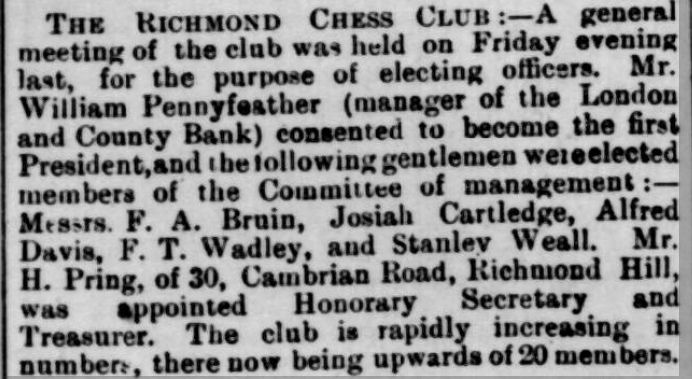

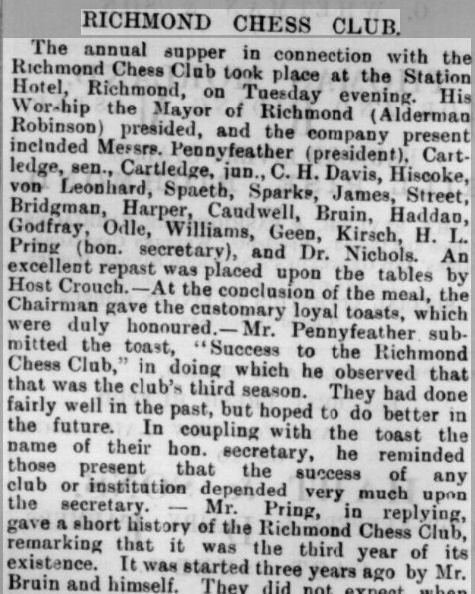

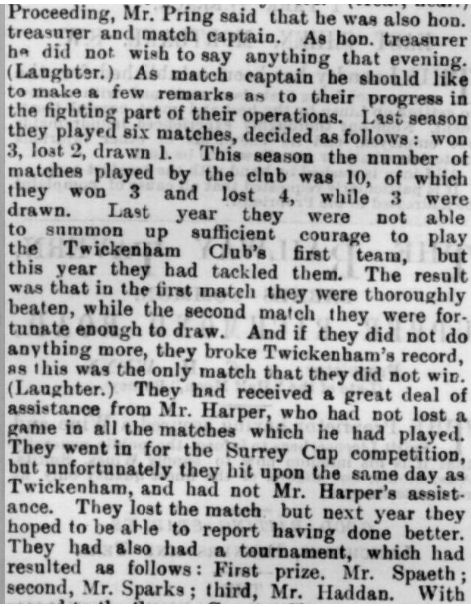

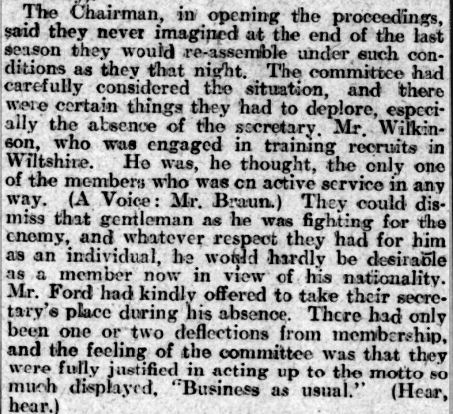

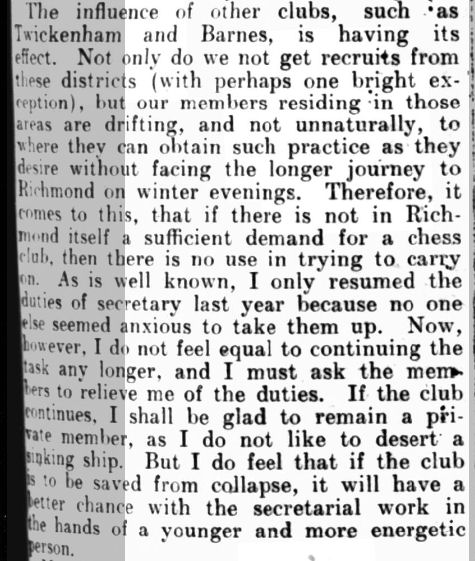

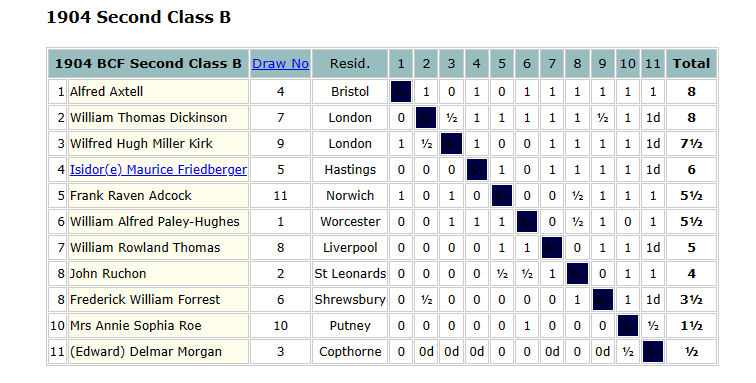

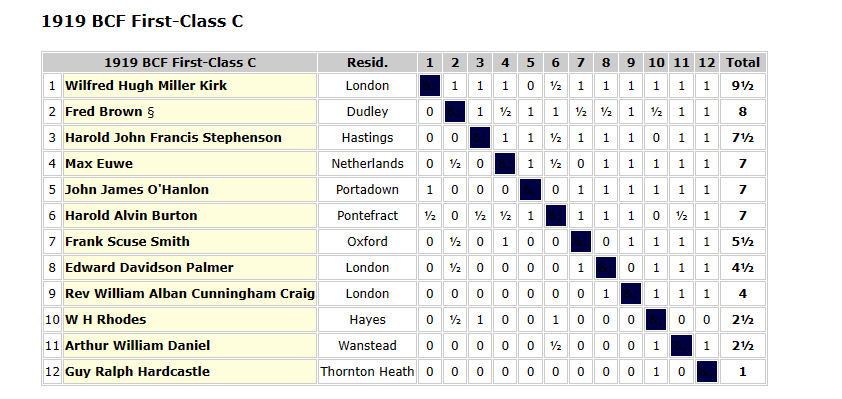

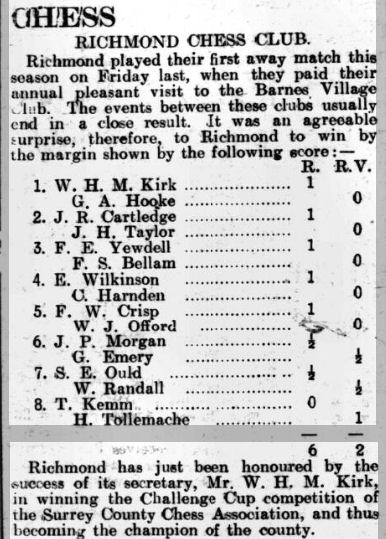

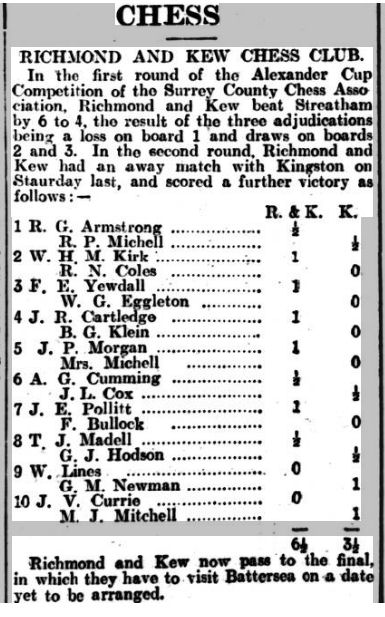

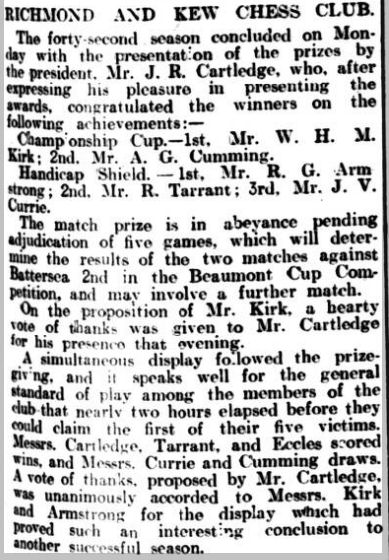

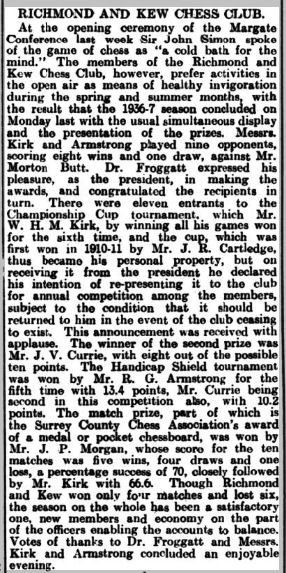

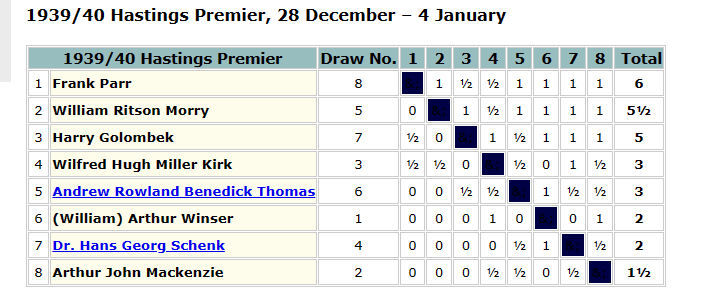

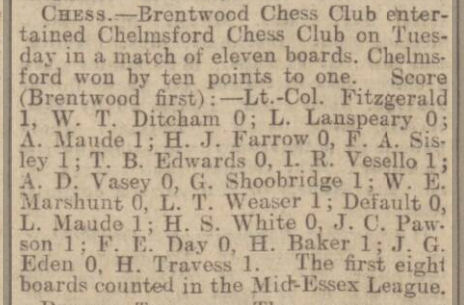

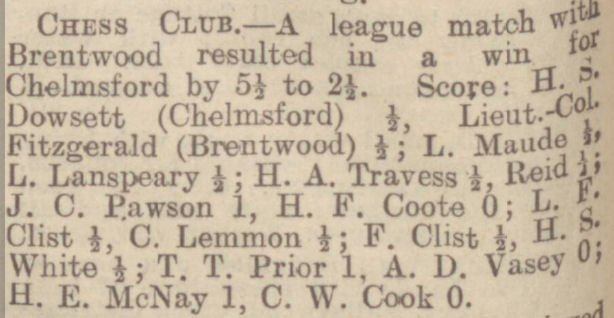

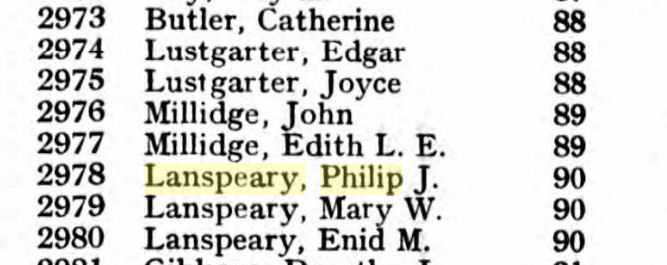

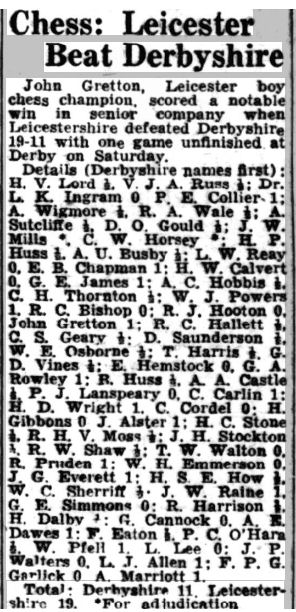

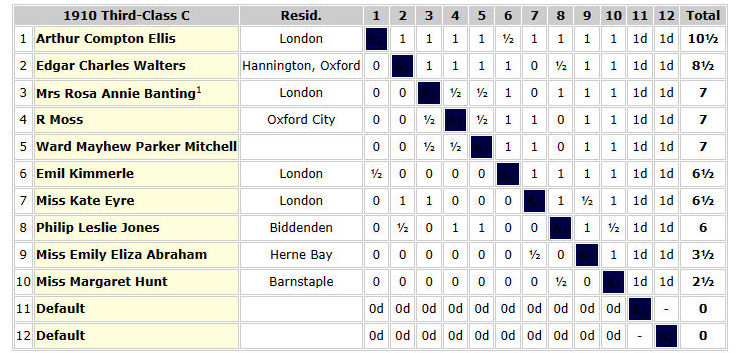

With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than

With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than