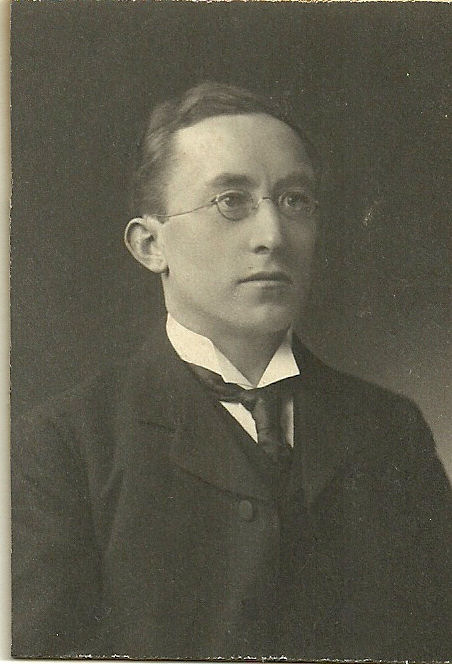

This is the third post in my series about George Edward Wainwright, sometime member of Twickenham, Guildford and Surbiton Chess Clubs, and one of the strongest English amateurs of his day.

You can read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

We left George in Surbiton in 1911, happily married, with four children and an important job in local government.

That summer he travelled abroad to play chess for the first time. He was playing top board for a team of members and friends of Hastings Chess Club who embarked on a tour of France and Switzerland, scoring 4½/5. I guess he was a friend, rather than a member.

Here’s a game from their match against the Union Amicale des Amateurs de la Régence, where he encountered the Russian diplomat Vassily Soldatenkov. (Click on any move of any game in this article and a Magic Pop-up Chessboard should, with any luck, appear.)

At this point he took a break from tournament chess, not playing in either the 1911 British Championship in Glasgow or the 1911-12 City of London Championship.

He wasn’t inactive, though: in November he took part in a simul at the City of London Club against the up and coming young Cuban Capablanca, where he managed to win his game.

In 1912 he didn’t have far to go for the British Championship, which took place just up the road from him in Richmond – the Castle Assembly Rooms to be precise, down by the river and opposite the Town Hall. Again, he didn’t take part, but was there as a visitor. (I’m considering a future series of Minor Pieces about some of the chessers who descended on Richmond that year.)

Wainwright was back in action in the 1912-13 City of London Championship, but without success. A large entry that year required three qualifying sections, with three qualifiers from each section making the final pool. He was well down the field in his section.

Throughout his life he remained loyal to his home county of Yorkshire: in those days there was no problem representing both Surrey and Yorkshire in county matches.

In this game from a Yorkshire – Middlesex match played in Leicester (a neutral venue) he beat one of his regular London opponents and a future Kingston resident.

Just two days later he took part in another simul against Capablanca, forsaking his usual tactical style and, after his opponent’s ill-advised queen trade, winning in the manner of – Capablanca.

The following year, he did better in the City of London Championship, this time qualifying for the finals by winning this game against a young Dutch master who had crossed the Channel hoping to make money by beating rich Englishmen.

By now it was 1914 and storm clouds were gathering over Europe. The London League kept going for one more season. Wainwright was representing the Lud Eagle club and won this game featuring a rather unusual sacrificial kingside attack in a match against West London. His opponent, William Henry Regan, was a stamp and coin dealer.

The City of London Championship managed to keep going for the duration, albeit with far fewer entries, giving George Edward Wainwright the opportunity to continue playing his favourite game.

He didn’t play in 1914-15 or 1915-16, but returned to the fray in 1916-17. Understandably rusty, he finished in last place behind Edward Guthlac Sergeant. The following year, fulfilling the prophecy from Matthew 20:16 (The last shall be first), later repeated by Bob Dylan (The loser now will be later to win) he shared first place with Philip Walsingham Sergeant (EG’s second cousin) and Edmund MacDonald, winning the play-off and so taking the title for the second time.

He was unsuccessful in defending his title in 1918-19, finishing in midfield behind the Latvian master Theodor Germann as chess started to wake up again following the end of hostilities.

In 1919 the British Chess Federation celebrated with a Victory Tournament in Hastings, where Capablanca won the top section ahead of Kostic. The Ladies’ Championship was included but the title of British Champion itself wasn’t awarded. While in the country, Capa gave a simul at the City of London Club, and, for a third time, lost against Wainwright.

Meanwhile, there were some important changes in Wainwright’s personal life. There was a major reconstruction of local government in 1919: the Local Government Board was abolished, its powers being transferred to the newly created Ministry of Health. It seems likely that at this point Wainwright, a wealthy gentleman whose children had now grown up, decided to retire. At some point in 1920 he and his wife moved to Alice’s home village of Box, Wiltshire. Box is situated in the beautiful Cotswolds, on the A4 between the city of Bath and the market town of Corsham.

The village’s previous claim to chess fame was as the birthplace of Thomas Bowdler (1754-1825), who, when he wasn’t expunging Shakespeare’s rude words, was one of the strongest English players of his day.

The Wainwright family settled in a cottage called Netherby, near the centre of the village, now a Grade 2 listed building. Very charming it looks too.

The Reverend Vere Awdry and his family moved into Lorne House (now a Bed & Breakfast establishment), next to the railway station on the road to Corsham, also in 1920. They’d arrived in the village in 1917, and had lived at two previous addresses there. He and his young son Wilbert used to spend hours watching the steam trains pass by. Many years later, Wilbert, now the Reverend W Awdry, would be inspired by this memory to write the Thomas the Tank Engine books, much loved by generations of young children, including me. George and Vere, as prominent members of the village community, would surely have known each other, and George would have known young Wilbert as well.

By 1920 things were back to normal, and George Edward Wainwright, now retired, was one of those selected for the British Championship in Edinburgh: his first appearance for a decade. His address was given as London and Box in different newspapers, which suggests he’d just moved, or was in the process of moving.

Roland Henry Vaughan Scott was the slightly surprising winner, ahead of the hot favourite Sir George Alan Thomas. Wainwright scored a respectable 4½/11, not bad for a player in his late 50s.

In this game he launched a dangerous kingside attack in typical style, and his opponent wasn’t up to the defensive task. Scottish champion Francis Percival (Percy) Wenman, a former petty thief (of chess books) and later plagiarist, will be well worth a future Minor Piece.

It was now 1921 and time for the census enumerator to pay a visit to the Wainwright residence in Box. George and Alice were there, along with a visitor from Bradford, possibly a family friend, and a general servant.

You’ll find out what happened in the latter stages of his life and chess career next time.

Sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

Google Maps

chessgames.com

Britbase

Thanks to Gerard Killoran for information about Wainwright’s simul games against Capablanca.