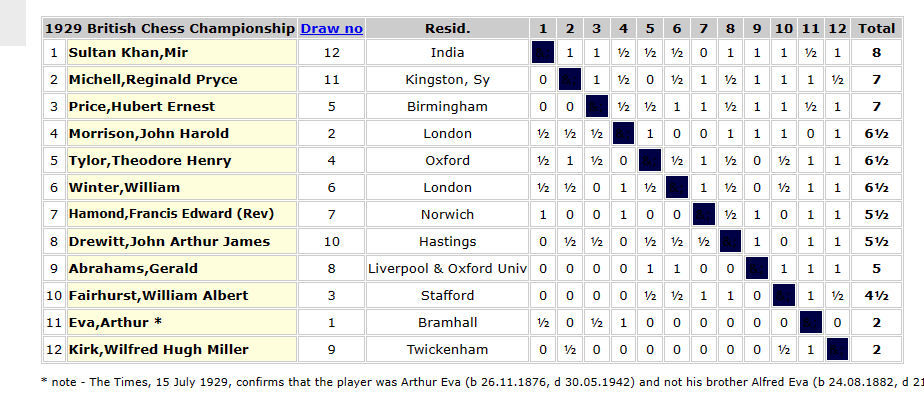

For several years in the 1930s, two blind players, Theodore Tylor and Rupert Cross, were amongst the competitors in the British Championship, restricted at that time to twelve players selected from the best in the country.

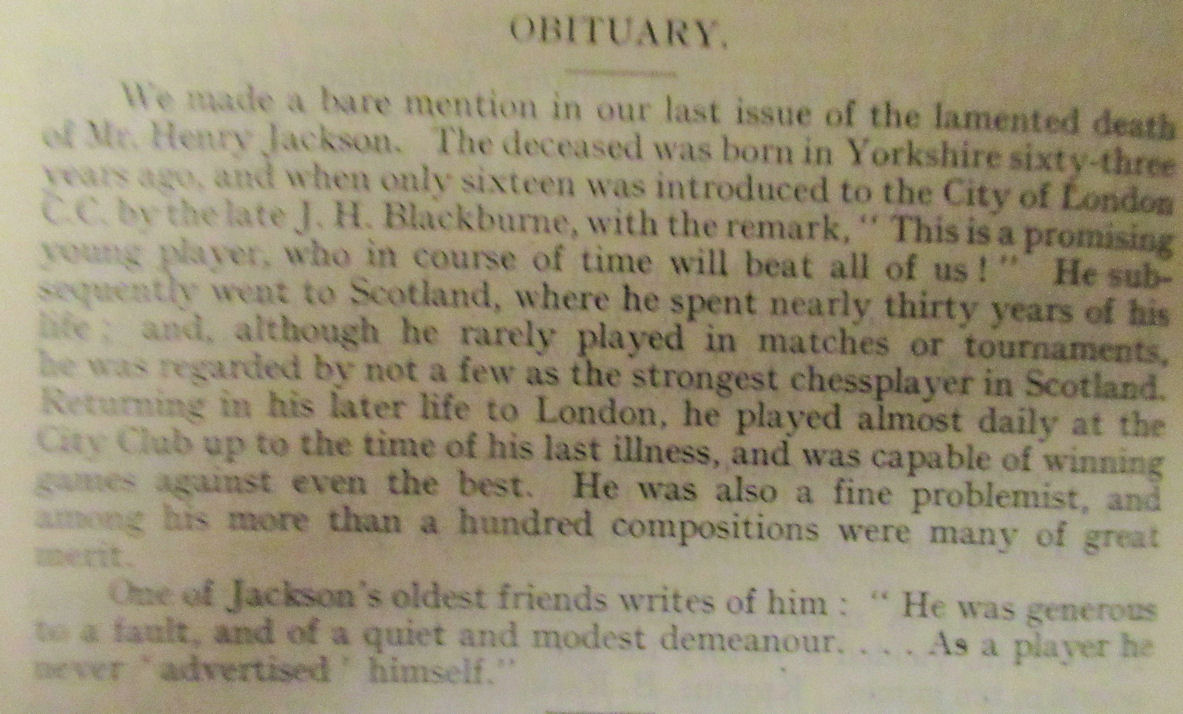

Tylor was a player of genuine master standard, competing with distinction against the best in the world, while Cross was a very strong county standard player. In addition, another blind player, Reginald Bonham, halfway between Tylor and Cross in age, was of similar strength to the latter, although he played most of his chess after the war. Tylor and Bonham were also formidable correspondence players, both winning the British Correspondence Championship on three occasions.

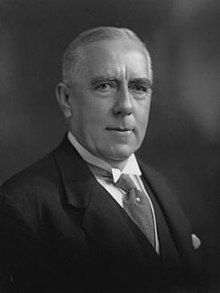

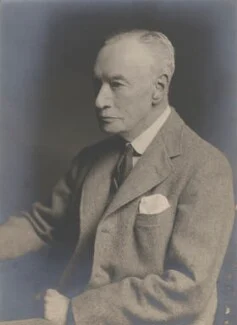

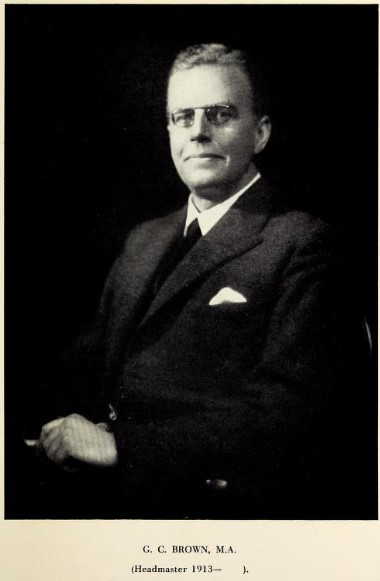

All three of these players had attended the same school, Worcester College for the Blind, where chess was promoted by their inspirational headmaster, GC Brown. This is his story.

George Clifford Brown was born on 29 May 1879, the son of a chemist and pharmacist from Brading on the Isle of Wight. His paternal grandfather, though, had been a master mariner from Yorkshire. In the 1901 census he, along with his brother John, was a pupil at Solent College in Lymington, just a short ferry ride from Yarmouth, on the other side of the Isle of Wight from Brading. By 1901 he was teaching at Shoreham Grammar School, on the Sussex coast, but he seems not to have stayed there long.

In 1902, George married Catherine Harvey Robertson Smith in Wealdstone, near Harrow, giving his profession as a schoolmaster and an address in Jersey. They would go on to have four children, Clifford (1906), Geoffrey (1909), Douglas (1911) and Joan (1913).

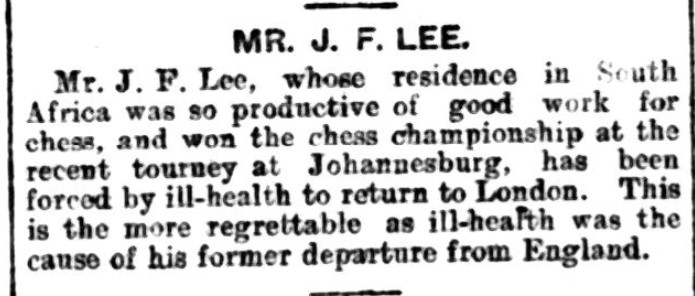

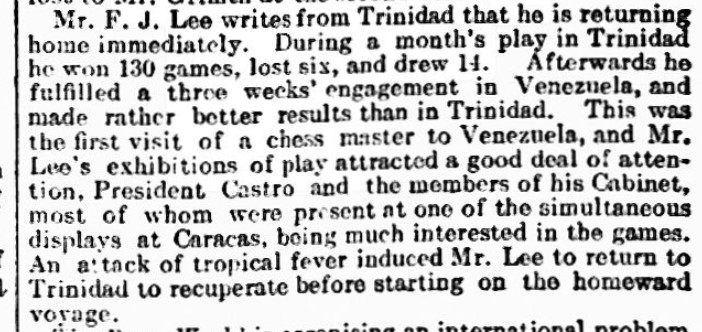

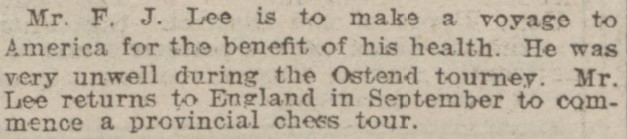

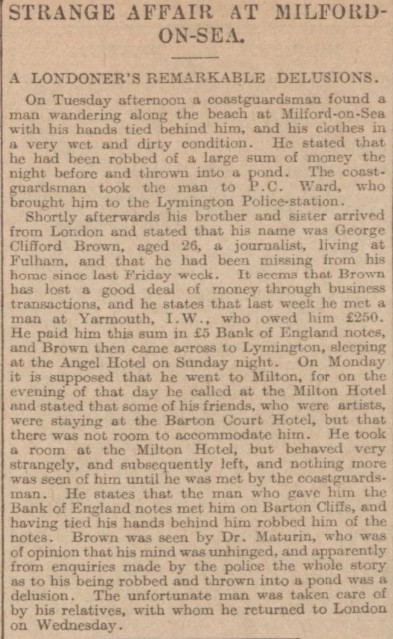

In 1905 something very strange seems to have happened, judging from these news items.

George’s sisters, Lilian and Muriel, ran a private school in Wealdstone called Hillside between 1900 and 1915: George might have been teaching there at some point, and might possibly, I suppose, have met Catherine there.

It seems he wasn’t suited to the world of journalism and publishing, and returned to teaching, by 1907 becoming one of the principals of Tollington Park College, a private school near Finsbury Park, in North London which had been founded by William Brown (as far as I know no relation) in 1879.

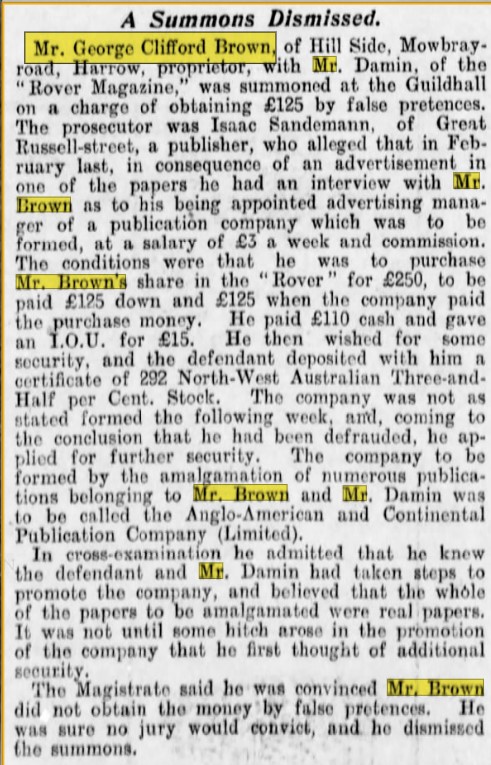

At the same time he was studying for an external degree at London University, graduating in 1910 with a second class degree in Modern European History.

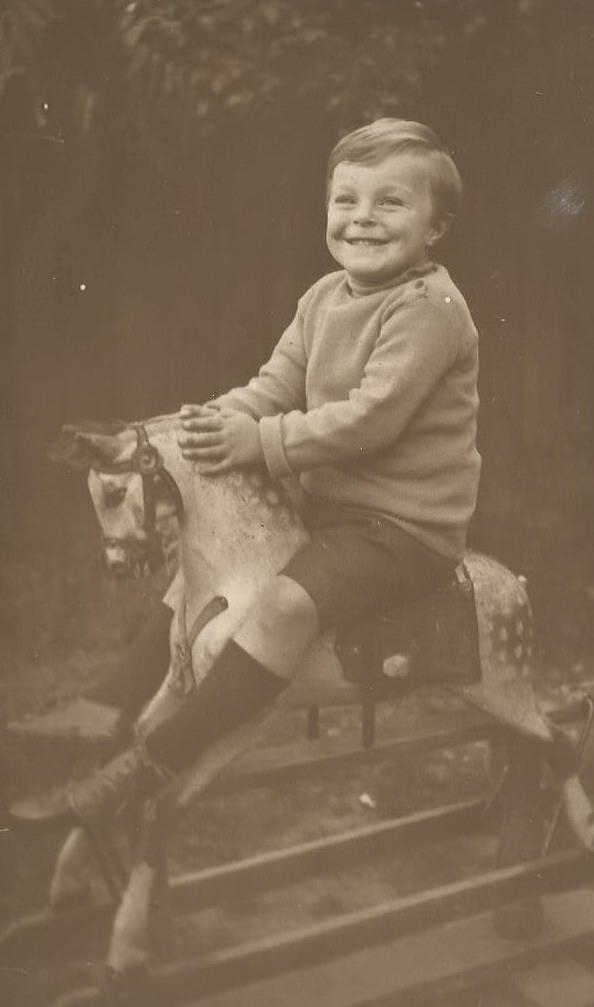

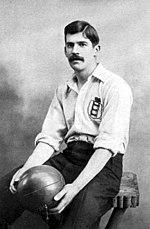

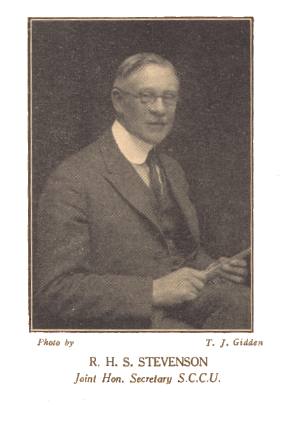

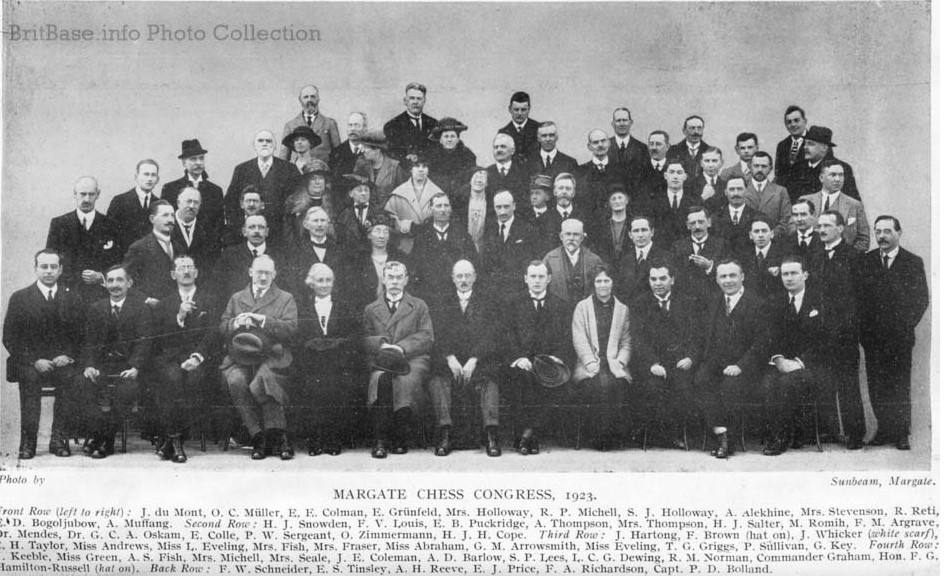

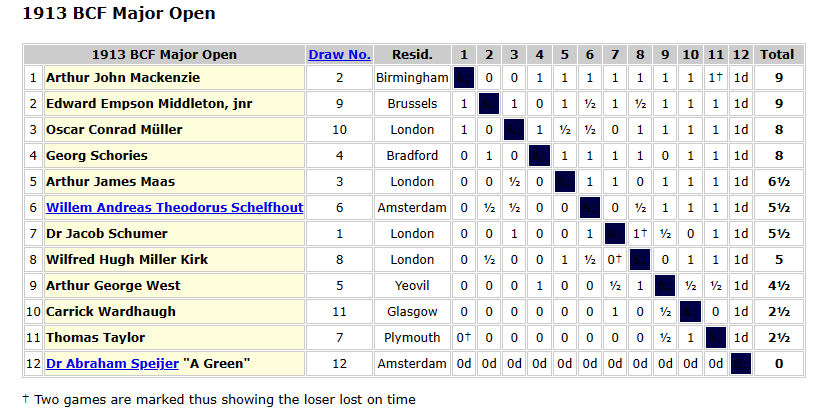

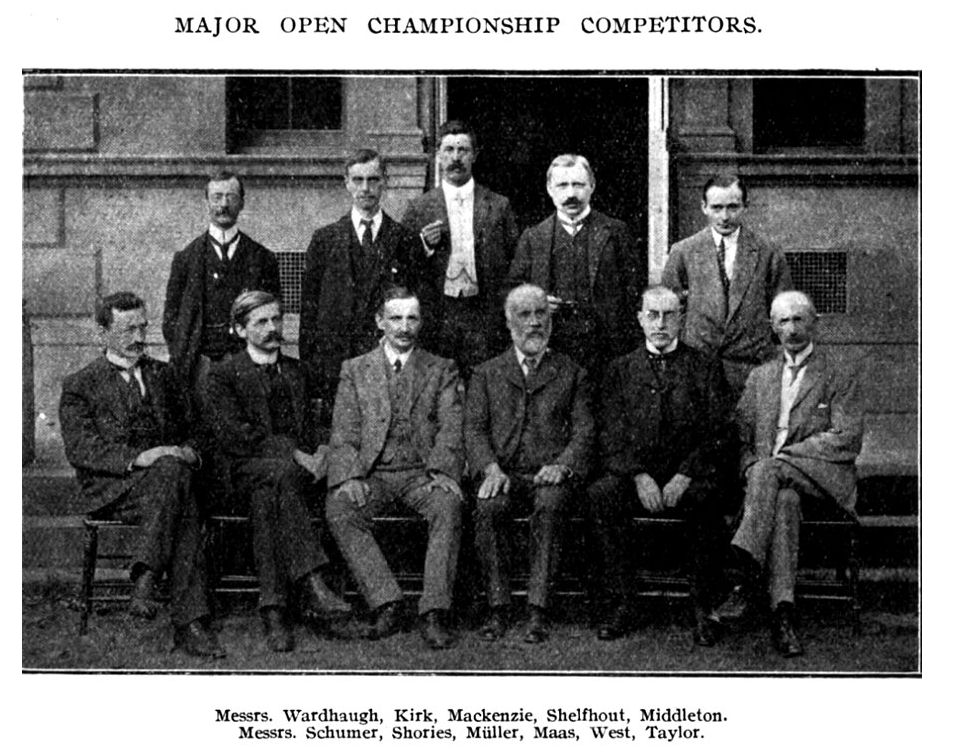

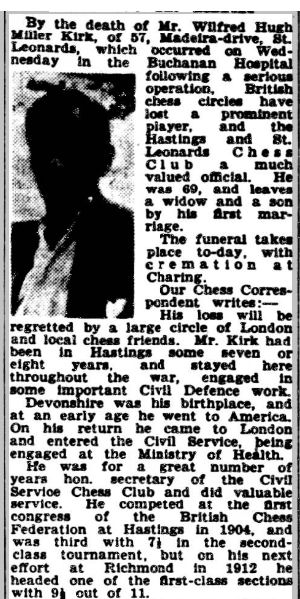

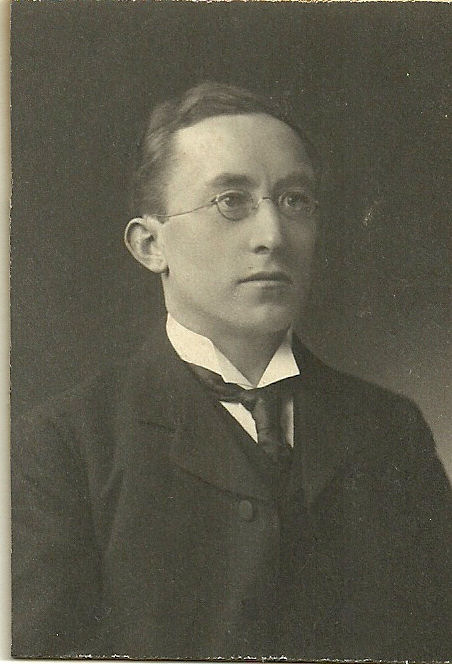

Here he is, and there, on his left, is Alfred Dudley Barlow, whom he would later meet over the chessboard on at least two occasions.

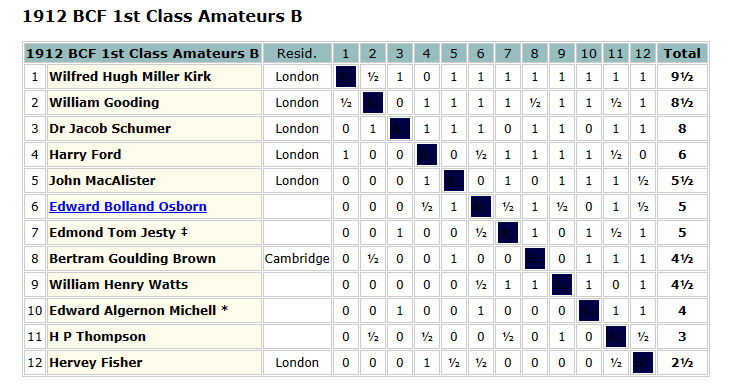

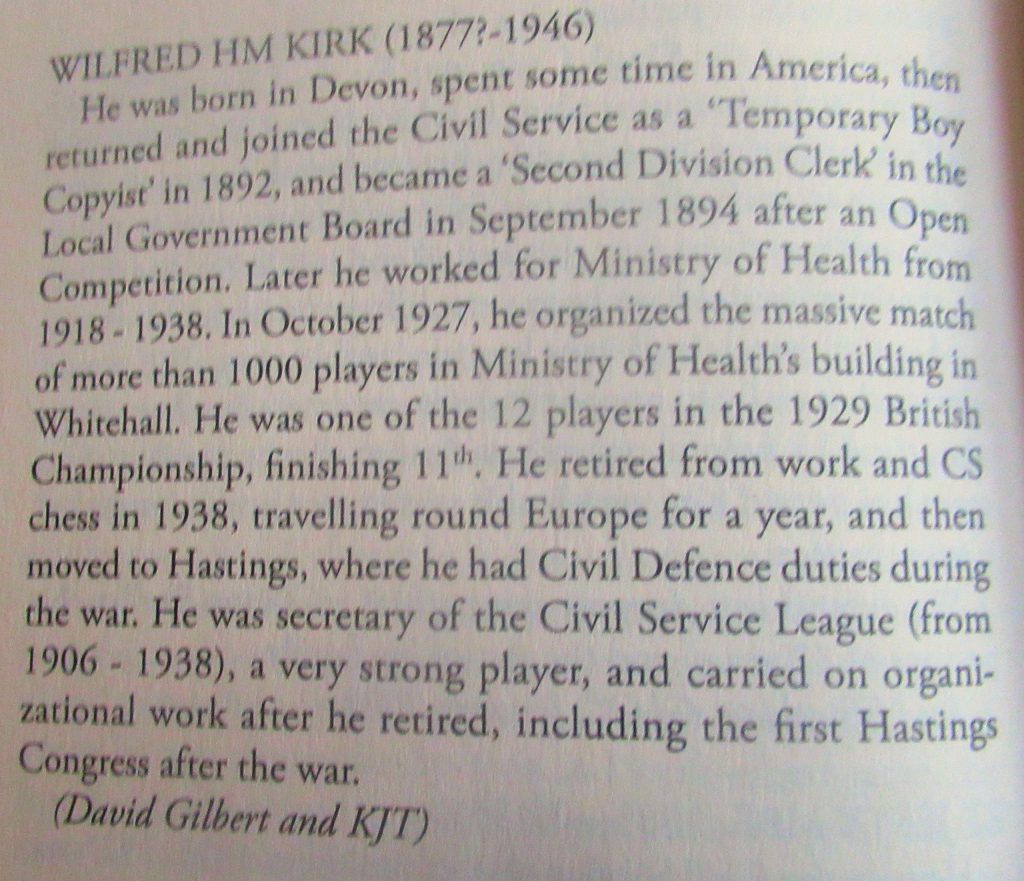

He was still at Tollington Park in the 1911 census, but left in 1912, in part due to young Douglas being unwell, and, in January 1913, started a new job as Headmaster of Worcester College for the Blind. A public school for boys with visual impairments, it was struggling financially at the time, and there were only five pupils there when he arrived. One of them was Theodore Tylor, who was already playing chess, and, as Brown was himself a chess enthusiast (he ran a club at his previous school) the two must have bonded.

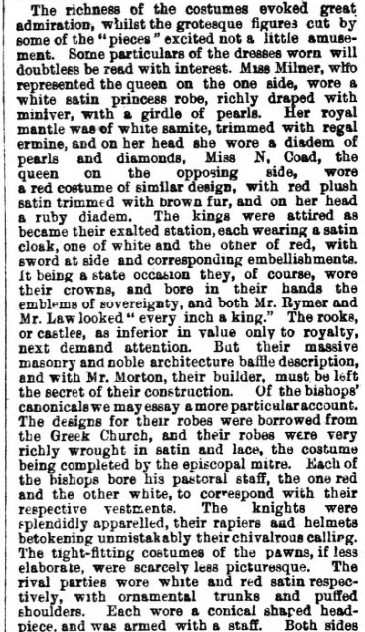

Although he had only attended a small private school himself, Brown was a supporter of the Victorian and Edwardian Public School ethos, where excelling at games was considered almost as important as academic success. He was very keen to promote games at which the blind could compete on level terms with their sighted contemporaries, and settled on rowing and chess, which are both practised while seated. He also encouraged swimming and adaptive forms of football and cricket, and, Chris McCausland will be delighted to hear, would later introduce dancing lessons.

He soon started a chess club, encouraging all the boys to learn chess, and, by 1916, they were good enough to win the Worcestershire Public Schools Chess Championship for the first time, an event they would win on almost every occasion for more than twenty years.

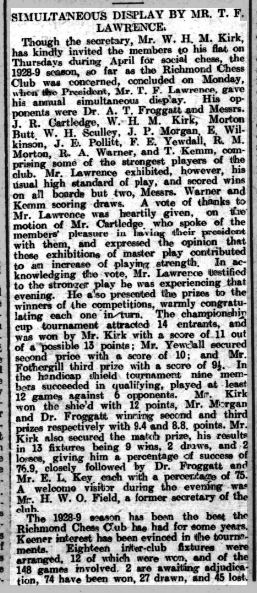

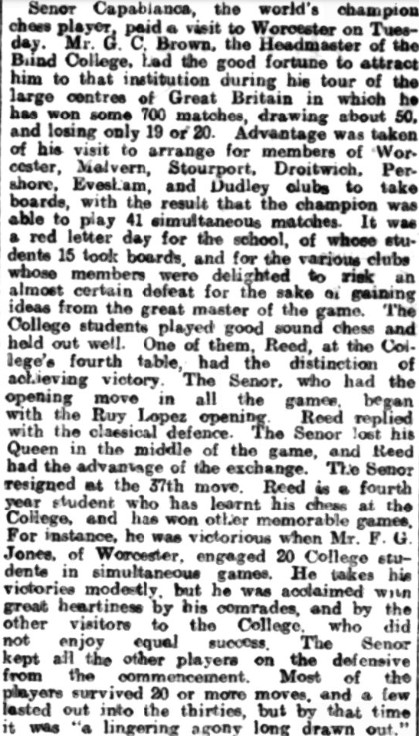

Every year a star player was invited to give a simultaneous display against the students, who were joined by players from other schools and clubs in the area.

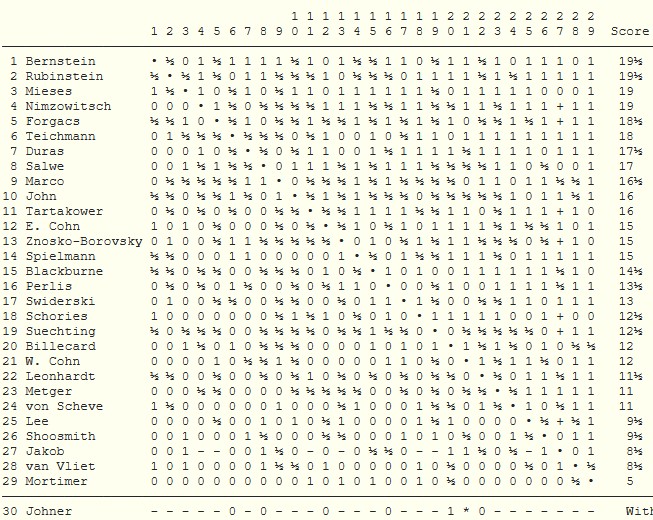

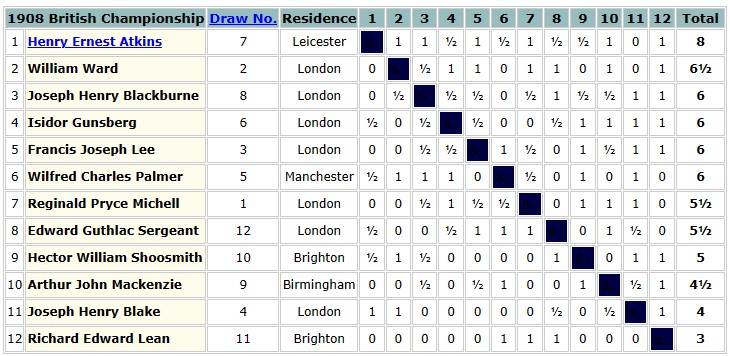

Visiting simul givers included Alekhine, Maroczy, Réti, Kostich, Sultan Khan, Sir George Thomas, Mieses, and, in 1919, none other than Capablanca, who even lost a game to one of his sightless opponents.

Here’s a photograph of the display in progress.

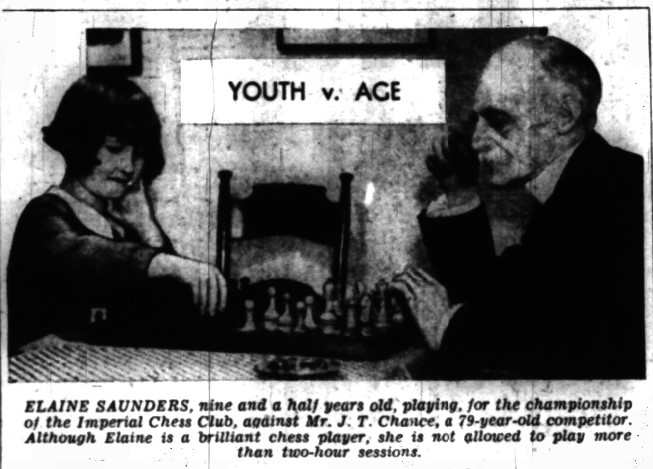

The winner, Edward Ingram Reed (1899-1951), from Monmouthshire, who later became a solicitor, continued playing county chess, both over the board and by correspondence, until the outbreak of World War 2. He came from a working class background – his father was a platelayer on the Great Western Railway – so must have been on some sort of scholarship. What a great day this must have been for him.

He’s seated on the right in this family photograph from about 1912.

We can also identify the college chess captain Vernon Charles Grimshaw (1901-1958), a headmaster’s son from London. By 1921 he was living in Brook Green, Hammersmith, just the other side of the park from where Amos Burn would move a few years later, and playing for West London Chess Club in matches against Richmond. He later became the Assistant General Secretary of the National Federation of the Blind.

Sadly, Reed’s game hasn’t survived, but this one has. Capa’s Stourport opponent might be considered rather unlucky to lose, having had the better of things most of the game. Click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up window.

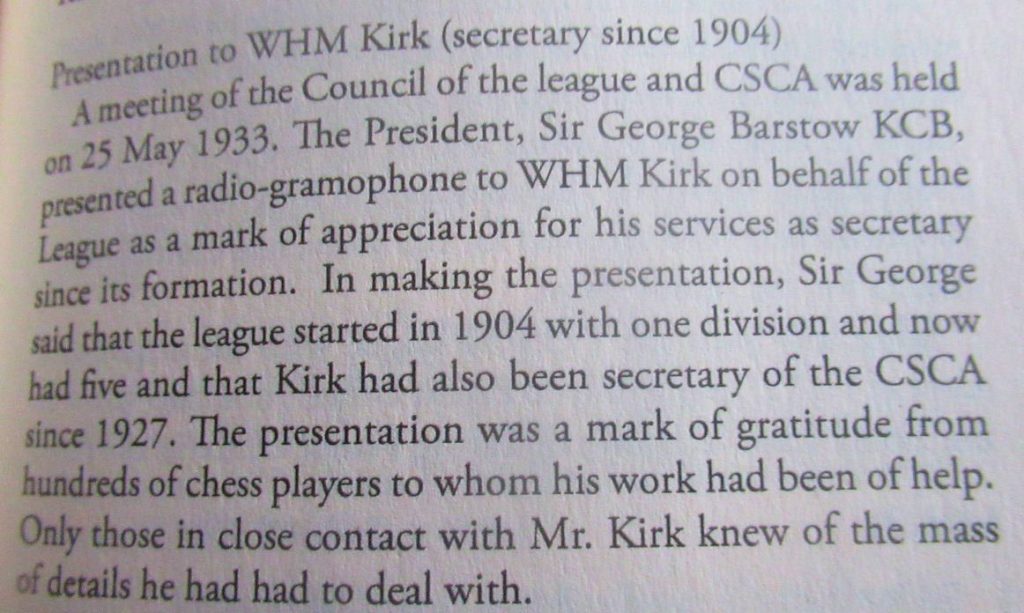

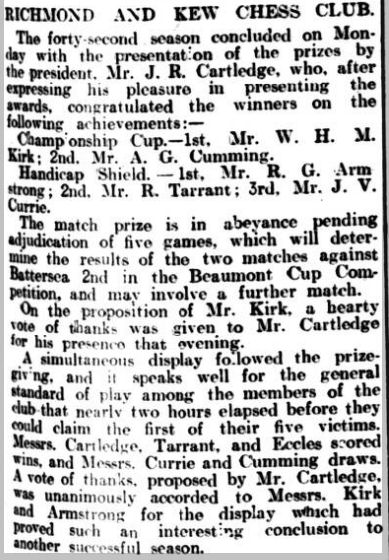

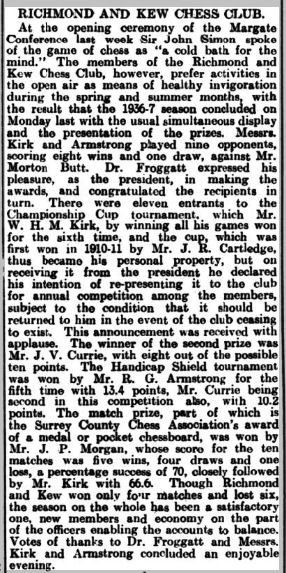

Brown later started to be involved with chess outside the college, taking up county chess and being elected Secretary of the Worcestershire County Chess Association.

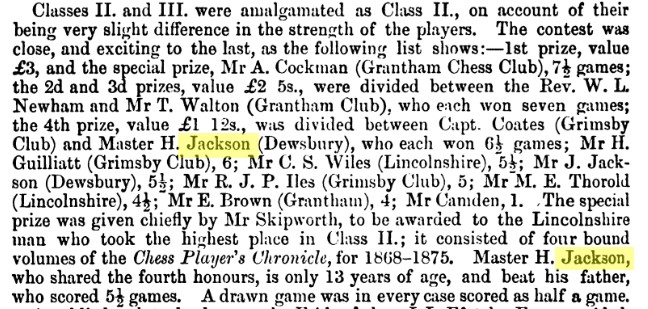

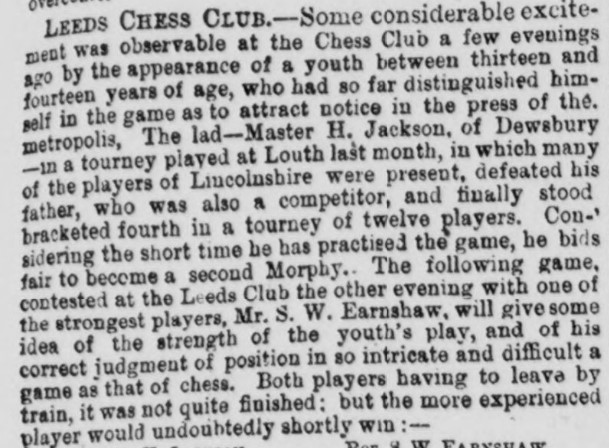

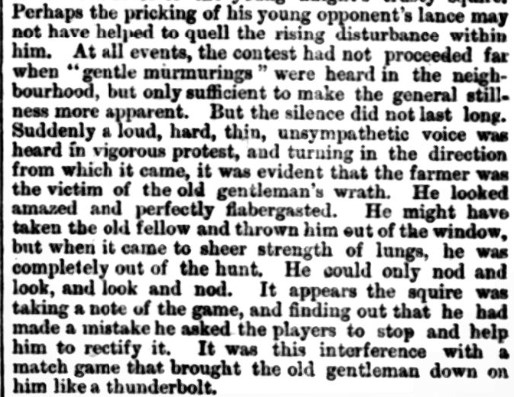

In 1924 he took part in his first tournament, entering the 1st Class B section at Weston-Super-Mare.

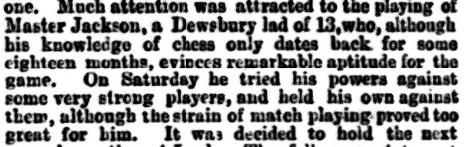

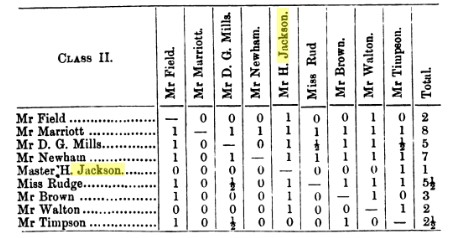

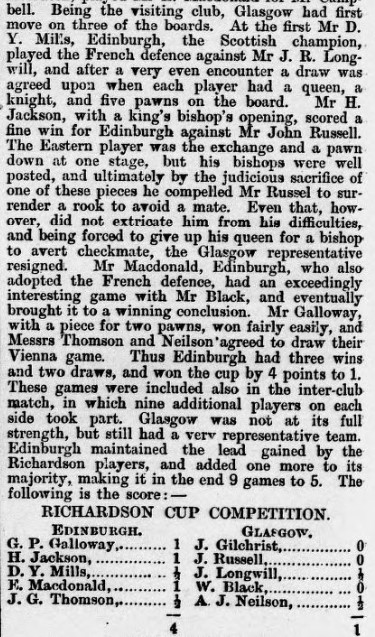

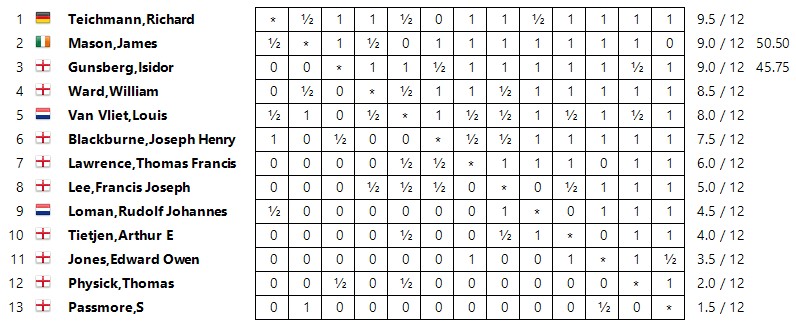

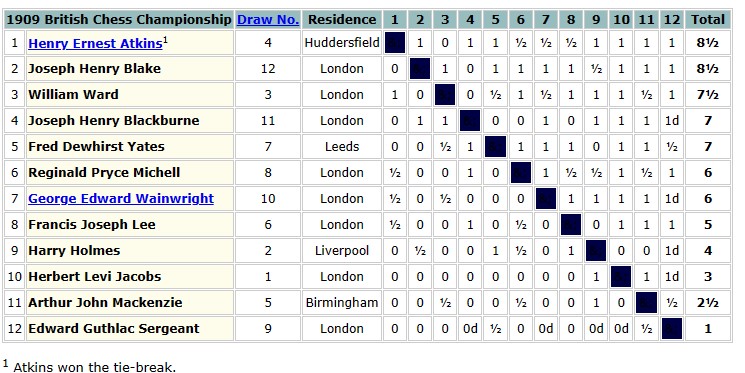

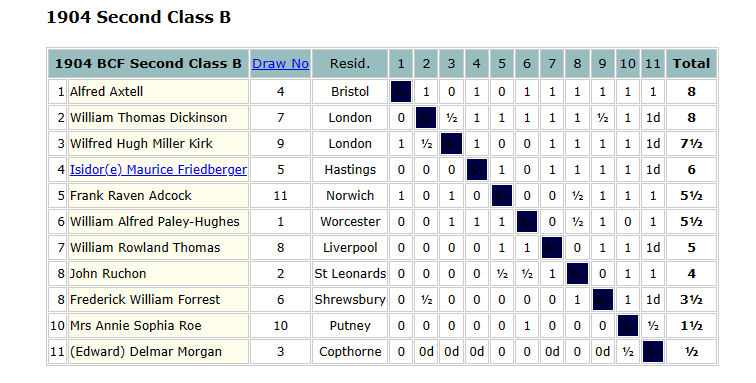

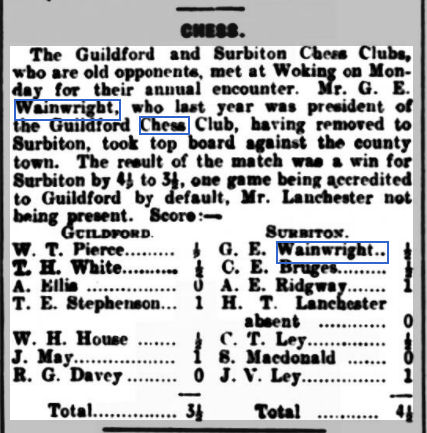

The results were as follows:

(1) Percival John Lawrence (Reading) 7½/9;

(2) F A Richardson (London) 7;

(3-4) Mrs. Agnes Bradley Stevenson (London), Rev. Ernest Walter Poynton (Bath) 5½;

(5) Hiram James Horace Cope (Ilfracombe) 5;

(6) George Clifford Brown (Worcester) 4;

(7) Samuel Waterman Viveash (Bristol) 3½;

(8) Ernest Fowler Fardon (Birmingham) 3;

(9) Edward Buddel Puckridge (Kent) 2½;

(10) Francis Frederick Finch (Bristol) 1½.

The clergyman from Bath beat him with some smooth positional chess.

In 1926 Alekhine visited Worcester College for a simultaneous display. George Clifford Brown put up some stiff resistance in his game, only losing control at the end of the session when his opponent would have had just a few games left.

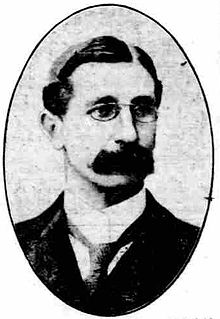

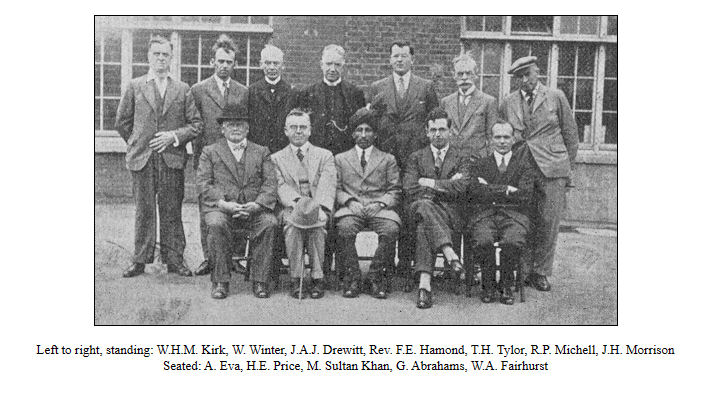

Here’s Alekhine, with Brown on his right, and young Rupert Cross on the right of Brown, with other Worcester College pupils who took part in the display.

You can read the whole Chess Pie article, along with a lot of other interesting material in this article by Neil Blackburn (simaginfan).

In the 1926-27 season Brown achieved a significant success, winning the Worcestershire County Championship, a title his pupil Tylor had won in 1923-24 and 1924-25. Another pupil, Bonham would later take the title on no less than 18 occasions between 1939-40 and 1960-61. His immediate successor, though, was former Minor Piece subject Dr Abraham Learner.

The school’s prowess at chess was recognised nationally in 1928 when they were awarded a British Chess Federation Schools Shield along with an annual medal to be awarded to the College champion.

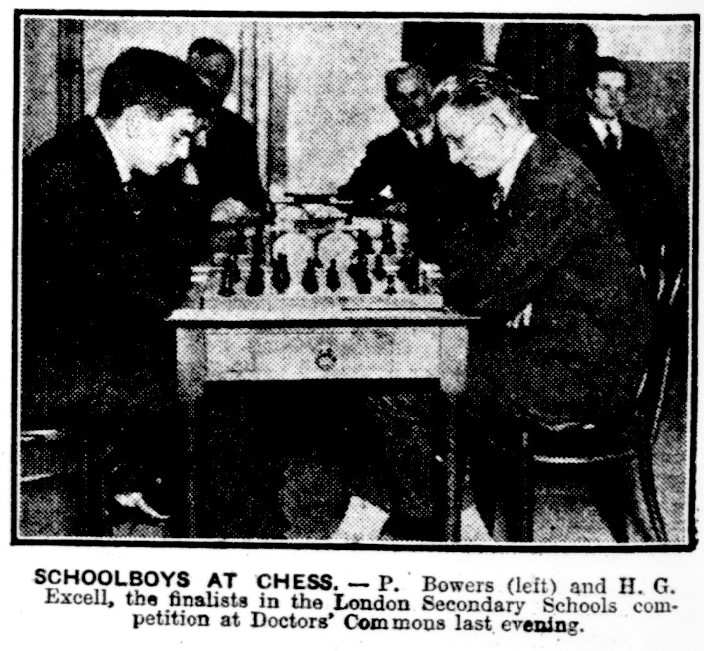

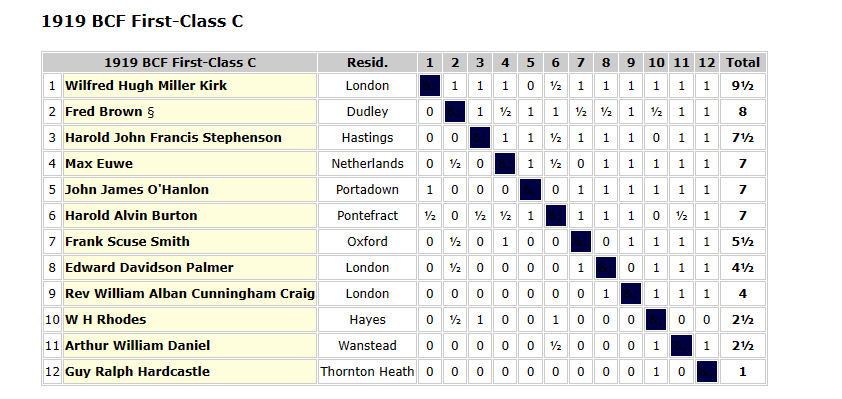

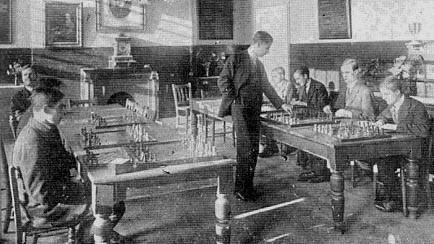

George Clifford Brown returned to tournament chess over Easter 1929, but he finished in last place in the First Class C section at Ramsgate, won by one of the competitors in the inaugural London Boys’ Championship.

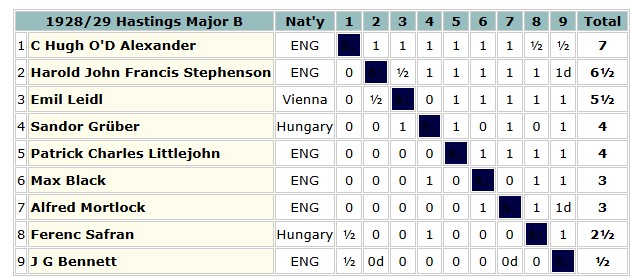

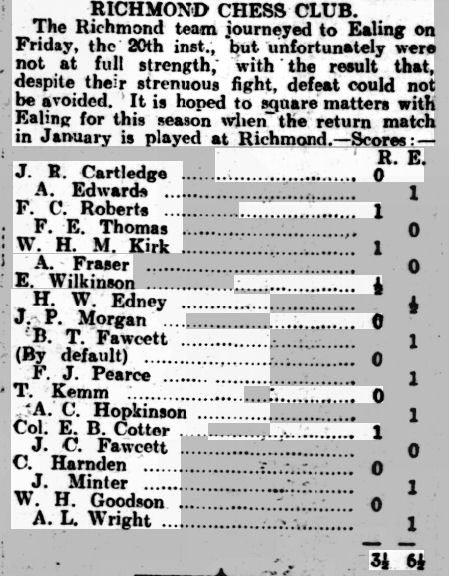

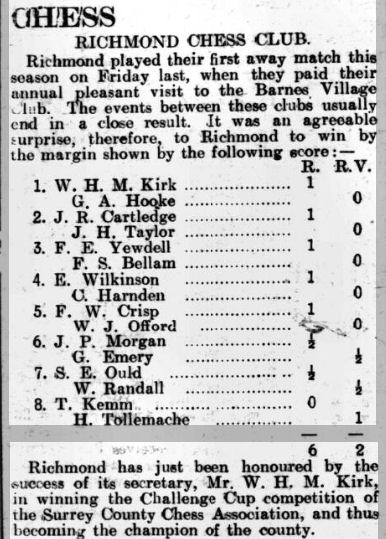

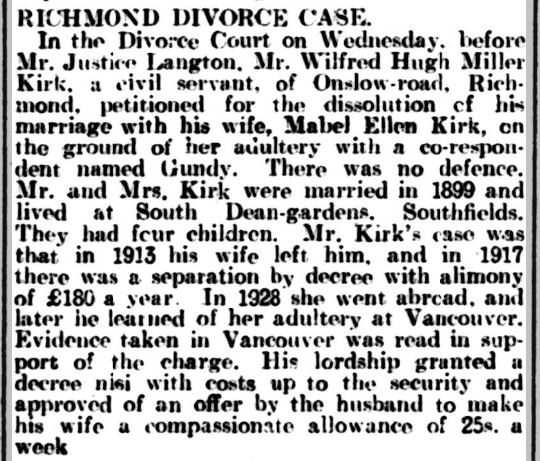

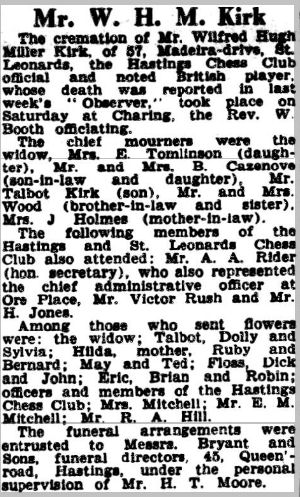

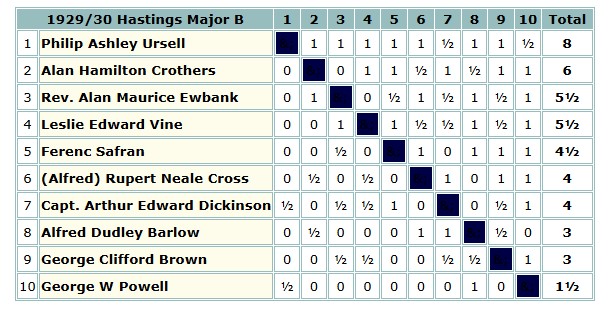

That winter Brown ventured to Hastings for the first time, scoring 3/9 in the Major B section, where he lost to his pupil Rupert Cross, and drew with the previously mentioned Alfred Barlow.

But on 19 May 1930 George Clifford Brown’s life was struck by tragedy, with the sudden death of his wife Catherine, who had, beyond her family duties, played an important role in helping her husband run the school.

The Evesham Standard (24 May 1930) paid tribute: She was a genial and charming hostess, a lady well fitted to have a kind of maternal oversight of a company of blind students, unfailingly cheerful and gracious in all sorts of circumstances, and mindful in every way of the peculiar claims which are made upon one occupying such a position. She will be greatly missed by many intimate friends, and particularly by the students and those chess players of the Midlands and West of England who were wont to gather at the College for chess matches.

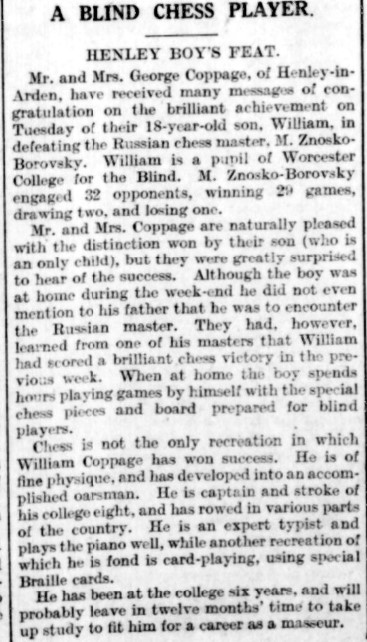

This blow didn’t curb his interest in chess, which still remained popular at the school. In November a pupil, William George Coppage (1912-1985), the son of a house painter (1911) and builder (1921) scored a victory against Znosko-Borovsky.

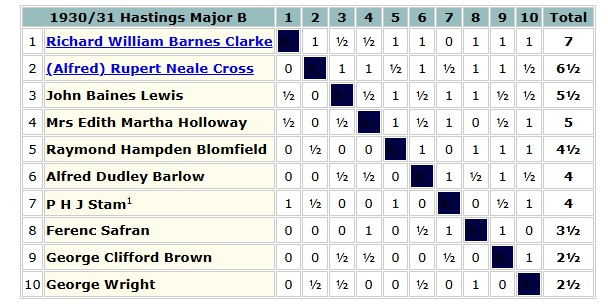

George Clifford Brown was back at Hastings that New Year, with a similar result in the same section as the previous year. This time he lost to both Cross and Barlow, as well as to the winner, the future Sir Richard ‘Otto’ Clarke, who would much later devise the first British Chess Federation grading system.

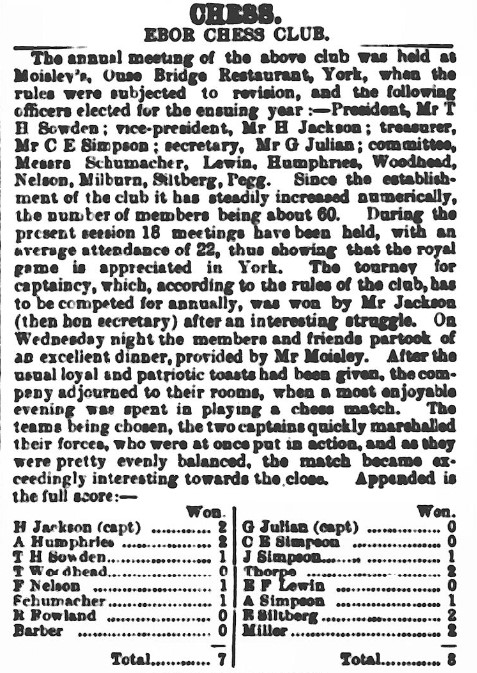

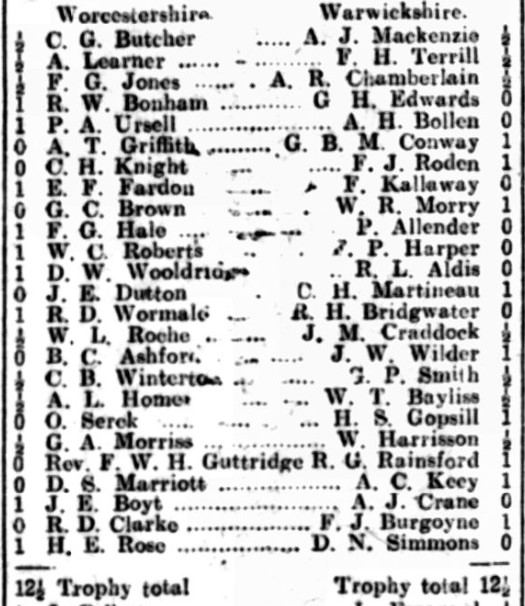

On 7 February 1931 Worcester College hosted a 100 board match between Worcestershire and Warwickshire. The top 25 boards counted towards the South Midlands County Championship.

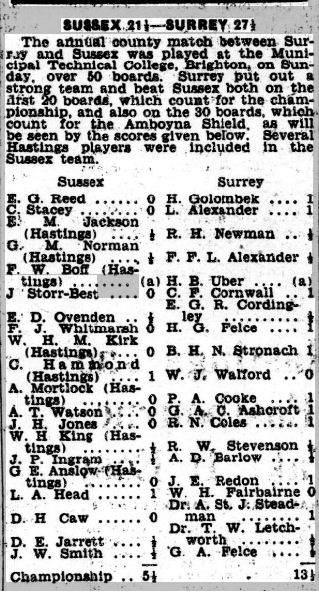

You’ll notice that Brown lost to Ritson Morry on Board 9, while Bonham won his game on Board 4.

Architect Arthur Troyte Griffith, on Board 6, was a close friend of Edward Elgar (who, as a young man, had taught music at Worcester College) and the dedicatee of one of his Enigma Variations, which you can hear here conducted by another of Elgar’s great friends, Sir Adrian Boult.

Three of Brown’s children were also involved: Clifford and Geoffrey both played on lower boards, neither troubling the scorer. Their sister Joan was on hand to welcome the players and provide refreshments, also making a presentation to the Warwickshire top board to mark his forthcoming retirement to Hastings.

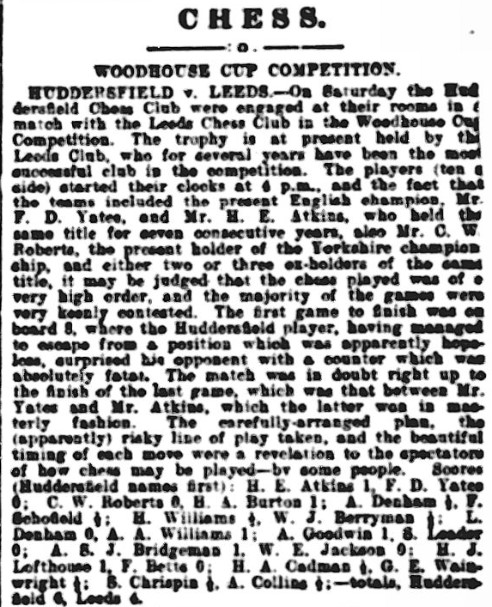

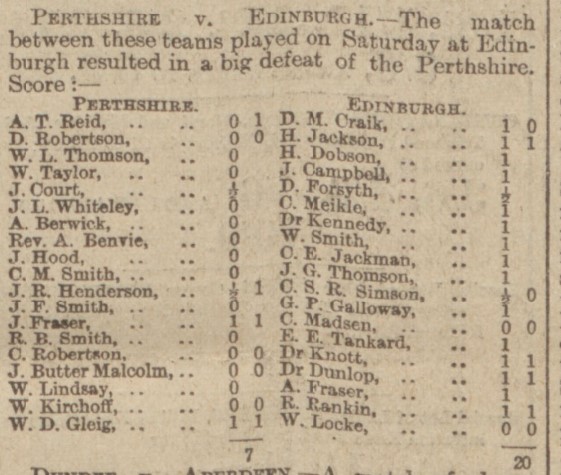

Warwickshire won the match by the narrowest possible margin, but, of greater significance, it was announced that the school would be hosting the British Championships that August, a considerable coup, not just for the Headmaster but for the whole school community.

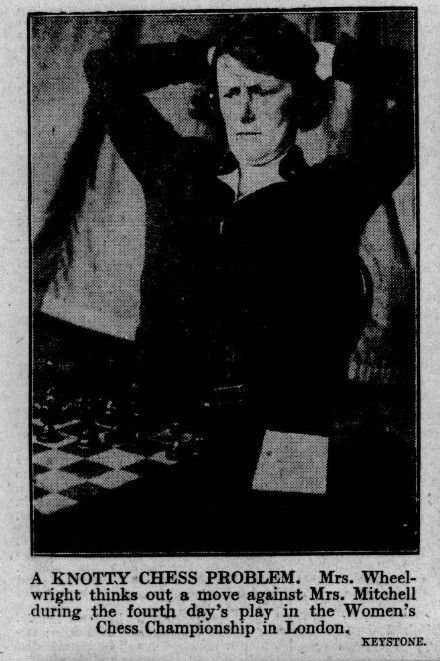

The school community was well represented: Tylor played in the Championship, won by Yates, just ahead of Sultan Khan and Winter. Cross was in the Major Open, won by the young Vera Menchik, while Bonham shared third place in the Major Open Reserves, with Ritson Morry in mid-table and BH Wood bringing up the rear.

One of their students also took part: Barnet Ellis (1914-1974), born in Leeds, the son of a Ukrainian Jewish tailor, took park in the 2nd Class B section, where his opponents included future Leicester chess historian Don Gould and a young Russian boy named Rostislav Chernikeeff. Barnet later gained a 2nd Class Degree in Jurisprudence from Oxford University, going on to run a solicitor’s practice in Pickering, North Yorkshire.

The British Chess Magazine (September 1931) commented:

According to the rota it was the privilege of the Midland Counties Chess Union to hold the Congress in its area. It is fortunate that the Union had ideal opportunities of carrying out the Federation’ ambitious programme. Worcester has many attractions which appealed to the public as the large number of entries and visitors amply showed. The College for the Blind afforded the best accommodation. It is situated in a pleasant position outside the town. The various rooms and grounds were placed at the disposal of the visitors for every purpose that could be devised. The lounge and swimming pool especially were luxuries not often to be found at a Chess Congress. Above all the Union is to be congratulated upon its organising officers! A. J. Mackenzie, president of the Union, as an old hand experienced in Congresses, was probably quite at ease in leaving the arrangements in the hands of the headmaster of the College, G. C. Brown, M.A. It is only fair to state that the exceptional success of the Congress was due to the quiet organisation and to the general courtesy and welcome that was extended to every one by Mr. Brown and the members of his family and staff who outdid one another in their efforts to make things go smoothly.

You can find full details of the event, along with some games, on BritBase here.

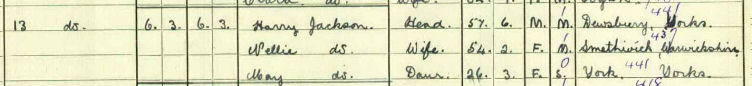

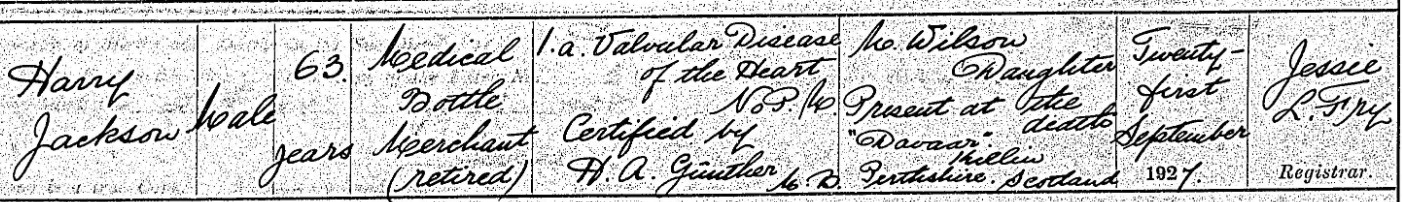

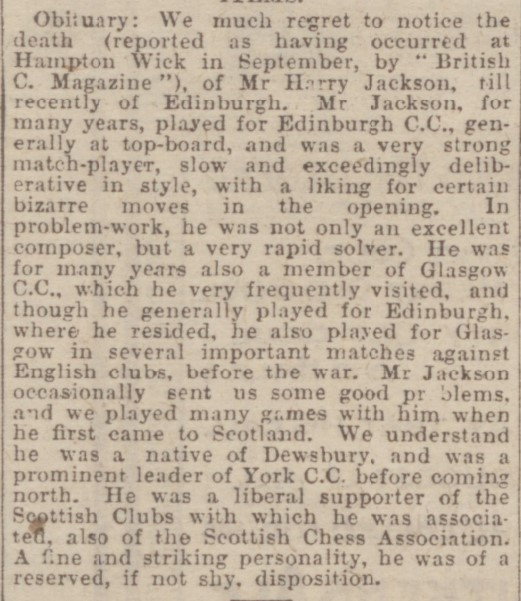

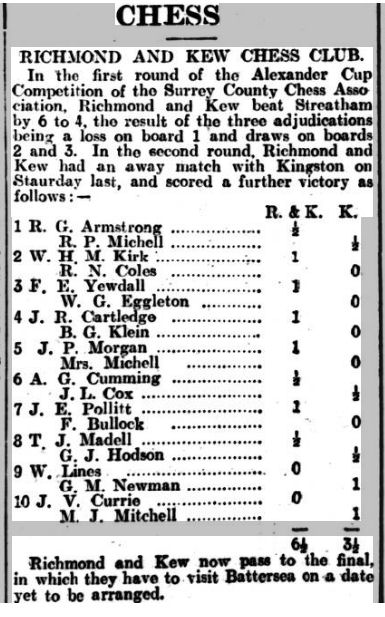

One of Worcester College’s regular match opponents were Oxford University. In 1931 Brown faced a future multiple Scottish champion, coming away with half a point.

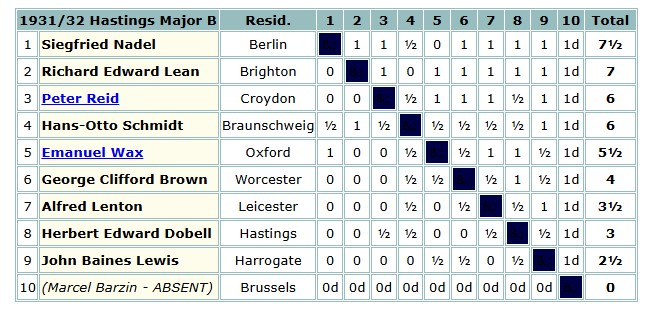

He was back again at Hastings, again in the Major B section, over the 1931-32 New Year, where his opponents included my distant kinsman Alfred Lenton.

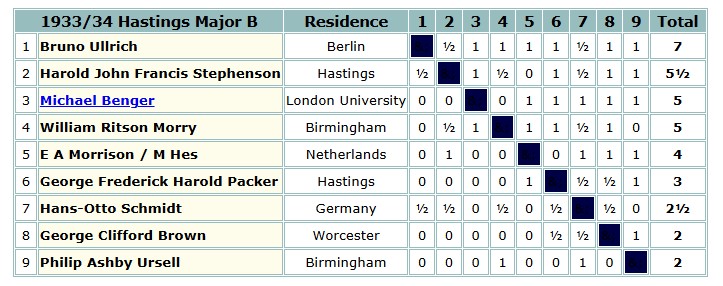

Brown missed Hastings in 1932-33, but was again in the Major B section in 1933-34, where he shared last place.

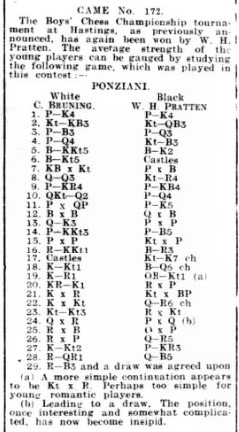

He went down to a crushing defeat in this game against former Sussex champion Harold Stephenson.

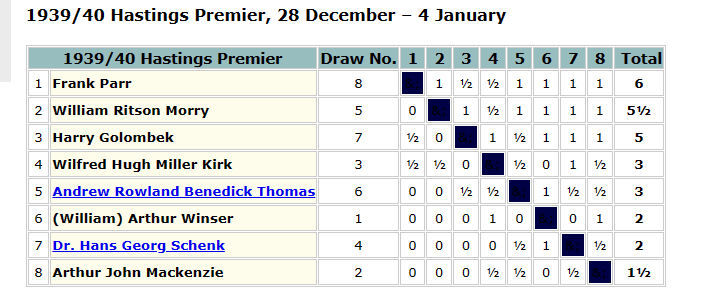

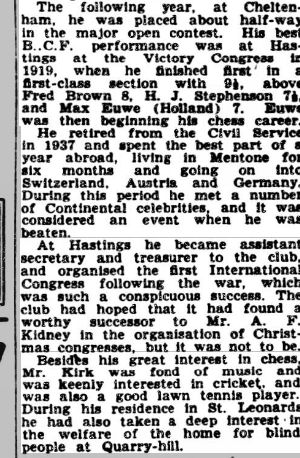

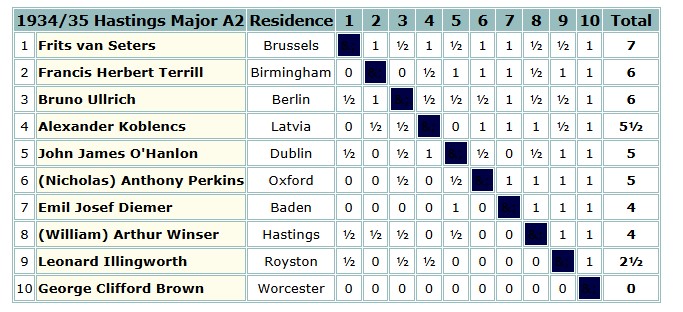

The following year he made what would be his final appearance at Hastings, where he unfortunately lost all his games, but this was a pretty strong international tournament, featuring Koblents, who would later achieve fame as Tal’s coach, and the eccentric Nazi Diemer, of Blackmar-Diemer Gambit fame.

The winner was a Belgian international player who had no problem outclassing the tail-ender.

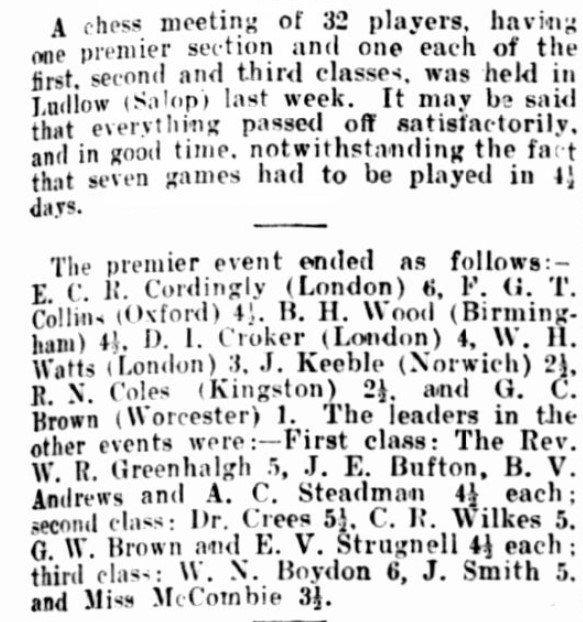

In August 1935 George Clifford Brown took part in a small tournament in Ludlow. Playing in the top section, his opponents included future chess author and historian R Nevil Coles, whom I played many years later.

His son Geoffrey also took part, winning a prize in the Second Class section.

This was to be his last tournament. We can sum him up as a strong club and county player who was rather out of his depth when competing against stronger opposition in the 1st Class sections at Hastings and elsewhere. It’s unfortunate that I’ve only been able to find draws and losses so far: if you have the scores of any of his wins I’d love to see them.

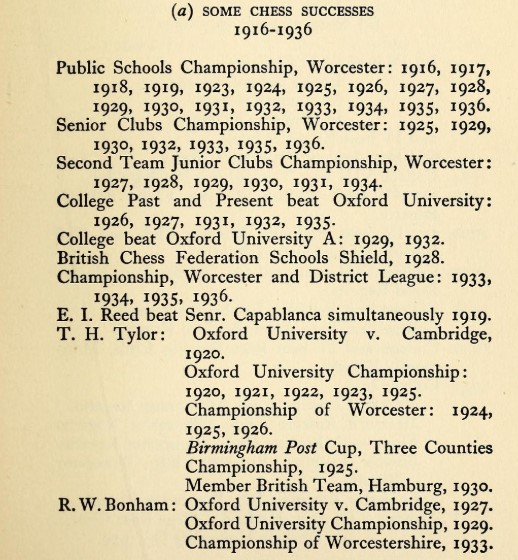

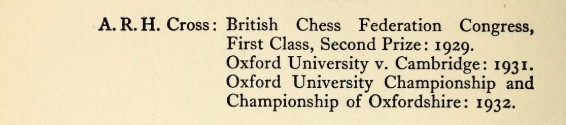

1936 marked the 70th anniversary of the school and a book was published marking the event.

There were several mentions of chess, and, at the end, a list of the school’s chess successes.

The First Seventy Years: Worcester College for the Blind, 1866-1936 by Mary G Thomas

The First Seventy Years: Worcester College for the Blind, 1866-1936 by Mary G Thomas

(The last name should be ARN Cross, not ARH Cross.)

I think that you’ll agree that these statistics are extraordinary, considering that this was a school which had only 5 (or 3, sources differ) pupils when Brown arrived, and, at its peak only 45 or so, and that they were all either totally blind or had severely limited vision.

The number who went on to study at Oxford or Cambridge, also listed in the book, is also notable, with some of them, including Bonham, the son of a butcher, and Ellis, the son of a tailor, coming from non-academic backgrounds.

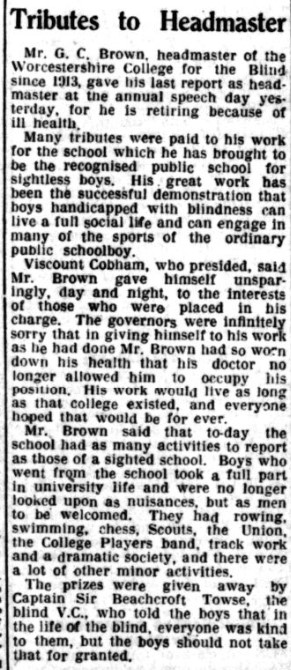

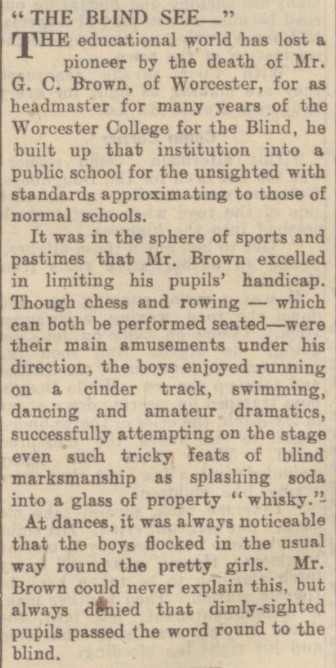

George Clifford Brown was clearly an outstanding and inspirational headmaster, but by now age was catching up with him, and the strain of running the school was perhaps affecting his health. In 1938 he was forced to take early retirement.

Brown died on 16 July 1944, at the age of 65

George Clifford Brown should be remembered as a pioneer of chess for the blind as well as a devoted and popular headmaster for a quarter of a century.

In the rowing world, too, he’s remembered as a pioneer of adaptive rowing, now known as pararowing, and thus as a pioneer of the whole concept of parasports. I’m sure he’d have been delighted to see the success of the Paralympics today, but perhaps also disappointed that not more has been done to promote chess for children with visual impairments.

On the surface, and wearing my chess hat, everything seems wonderful. Brown was clearly an extraordinary man who was passionate about chess, passionate about his pupils, and passionate about helping them thrive as sightless people in a sighted world. Wearing my rowing hat, if I had one, I would no doubt reach the same conclusion.

Behind the scenes, though, there were problems, which grew more acute after Catherine Brown’s premature death in 1930.

In 1931 the school received its first full inspection since 1915. Although it was, in general, highly favourable, a few suggestions were made as to how it might improve.

There was a concern about the use of unqualified staff: Reg Bonham had recently returned after completing his Oxford degree to teach mathematics and Braille, while the Oxford Rower LCR Balding had also joined without a teaching qualification. In 1936 he would marry Joan Brown. There were also suggestions that the organisation of the school was unsatisfactory, that the curriculum was too narrow, and that the academic standards in some subjects could be improved.

It’s notable that the 1928 prospectus included eight photographs of rowing and six photographs of chess, compared with seven photographs of classrooms and one of the school play. While this was no doubt wonderful for the boys who excelled at rowing or chess, or, in the case of Rupert Cross, both, there would surely have been doubts about whether they had their priorities right, and whether they should be doing more to ensure academic success rather than training students to live the life of a leisured Edwardian gentleman. It’s a debate which is still extremely relevant today, a hundred years on.

One of the pupils who gained a lot from chess was John (surname not available) who, in 1935, wrote (I’ve corrected a few mistakes):

Foremost in winter comes the inevitable chess. This fascinating game attracts almost universal interest in the college and matches frequently take place between the college teams and other clubs including, Oxford University, Birmingham City and many others. We have also held the Worcestershire Public Schools Championship for many years, and in 1928, carried off a shield awarded by the British Chess Federation. We also compete in several other chess leagues, and it may also be noted that in the last sixteen years the college has provided Oxford University with several chess champions. Tournaments and informal instruction circles are arranged; whilst chess masters are invited to give lectures and to play the members of the school simultaneously. During my short residence here I have met over the board: Sultan Khan (former British Champion), Maroczy, Sir George Thomas (Present British Champion), TH Tylor (a well-known competitor at the Hastings Congress and an Old Boy of the college), Herr Mieses and Fräulein Sonja Graf (the girl champion of Germany).

Another growing issue was one of discipline, which could be lax at times. Brown was warm, empathetic and approachable, taking a full part himself in all school activities, and clearly being held in great affection by all his pupils. But he wasn’t a strict disciplinarian, and perhaps the boys sometimes took advantage of him.

While efforts were made to broaden the curriculum and improve academic standards, the organisational problems were not addressed, and, the school archives reveal, their financial position was gradually spiralling out of control.

In 1936 the governors, concerned about the deteriorating situation as well as Brown’s nepotism, decided to take action. Brown had expensive tastes in food and drink, which he expected the school to pay for, and the local butchers and wine merchants were owed significant amounts of money. Joan, who had been employed as his housekeeper, had her post terminated, and his son (I presume this was Geoffrey, who was involved in rowing as well as chess) lost his retainer for contributions to social activities. He was also told that his own employment would be terminated by his sixtieth birthday: in fact he left slightly earlier than that. All this must have been extremely distressing to him, but schools have to do what they need to do to survive and be successful.

What happened after his departure? Chess still continued to be prominent in the school for some time, as would be expected with Reg Bonham on the staff. Perhaps the strongest player from this period was John Anthony Wall, who represented Oxford in the 1949 and 1951 Varsity Matches before becoming Britain’s first High Court Judge.

Years later, a pupil at The King’s School Worcester, Malcolm (again surname not available), recalled his contacts with his blind contemporaries:

I was at Worcester Kings School as a boarder from 1949/58, and have memories of playing chess for the school in matches versus the College for the Blind who produced good players under the excellent guidance of Mr RW Bonham, who beat me soundly (at chess, that is!) in 26 moves in a Worcester & District league match on the 8th December 1956.

In that same 1956/57 chess season, 5 boys from the College were entered into the Worcestershire County Individual Junior Championship (Under 18s). Between them they produced one of the finalists – Jones – who lost to me on 17th March 1957 in an exciting 44 move game which started at the College on 13th December and had to be adjourned because of time.

In 1987 Worcester College merged with Chorleywood College (for girls with little or no sight) to form a new school: New College Worcester. Do they still play chess? The website mentions board games and a Scrabble club, but there’s no specific mention of chess.

George Clifford Brown was a remarkable man who, although, like all of us, he had his faults, undoubtedly transformed the lives of many boys who were blind or had limited vision during his 25 year tenure as Headmaster of Worcester College. His opinion that chess is something which can help young people with disabilities integrate into the outside world is something that we’ve perhaps forgotten today. He would, I think, be saddened to see how, a hundred years later, so few children with visual handicaps seem to play the game.

His story prompted quite a few thoughts.

In the 1930s, while the blind boys in Worcester were playing chess so successfully, you might recall that the boys from Desford Approved School near Leicester were also taking part in competitive chess with success. You can read their story here and here. Although the two schools were dealing with very different pupils, they were both using chess to help disadvantaged boys, and both run by men who were considered progressive in many ways. There’s even a family connection. George’s youngest son Douglas Brown’s wife had a brother-in-law, an auctioneer in Market Harborough, who was distantly related to Sydney Gimson via the Symington soup and corsets family. It’s a small world.

I spent some years involved with what was, at first, a small family-run school which, although open to everyone who could pay, attracted a high proportion of children who, for a variety of reasons, didn’t fit in to mainstream schools. Comparing the two schools I can see quite a lot in common: many of the same strengths, and also perhaps some of the same weaknesses.

There’s also the wider question, which I alluded to earlier, as to whether secondary schools should focus purely on academic attainment and future earning potential, or whether they also have a responsibility to provide cultural and social capital. This is discussed in indirect terms, for instance, in Alan Bennett’s play The History Boys. I suspect I know what Brown’s view would be and, on a personal level, I think I’d agree with him.

With regard to children with disabilities, to what extent should we be helping them meet other children who share their disabilities, and to what extent should we be finding ways to help them make contact with the wider world? Ideally, of course, you want to do both, but perhaps our education system could do more of the latter.

Leading on from this, should we in the chess community be doing more to use chess to help children with a variety of disabilities? One of the great aspects of chess, for me, is that it has few barriers of this nature. We’re not just talking about children with visual disabilities, but also children with auditory and physical disabilities, not to mention children diagnosed with conditions such as ASD (autism) and ADHD. On several occasions I’ve tried to arrange meetings in schools to discuss this, but have found no interest in anyone even talking to me. Perhaps the demand from within schools isn’t there, but it certainly should be. If you know me well you’ll know my views.

You’ll be meeting some of the young chess players from Worcester College again in future Minor Pieces.

Sources and Acknowledgements

If you’re interested in taking the story further, there’s a lot of material readily available online.

If your interest is specifically on the chess side, I’d recommend the three-part series written by Neil Blackburn, from which I took two of the photographs here. Part 1. Part 2. Part 3.

If you’re interested in the college itself, start with The First Seventy Years: Worcester College for the Blind, 1866-1936 by Mary G Thomas, which you can read online here.