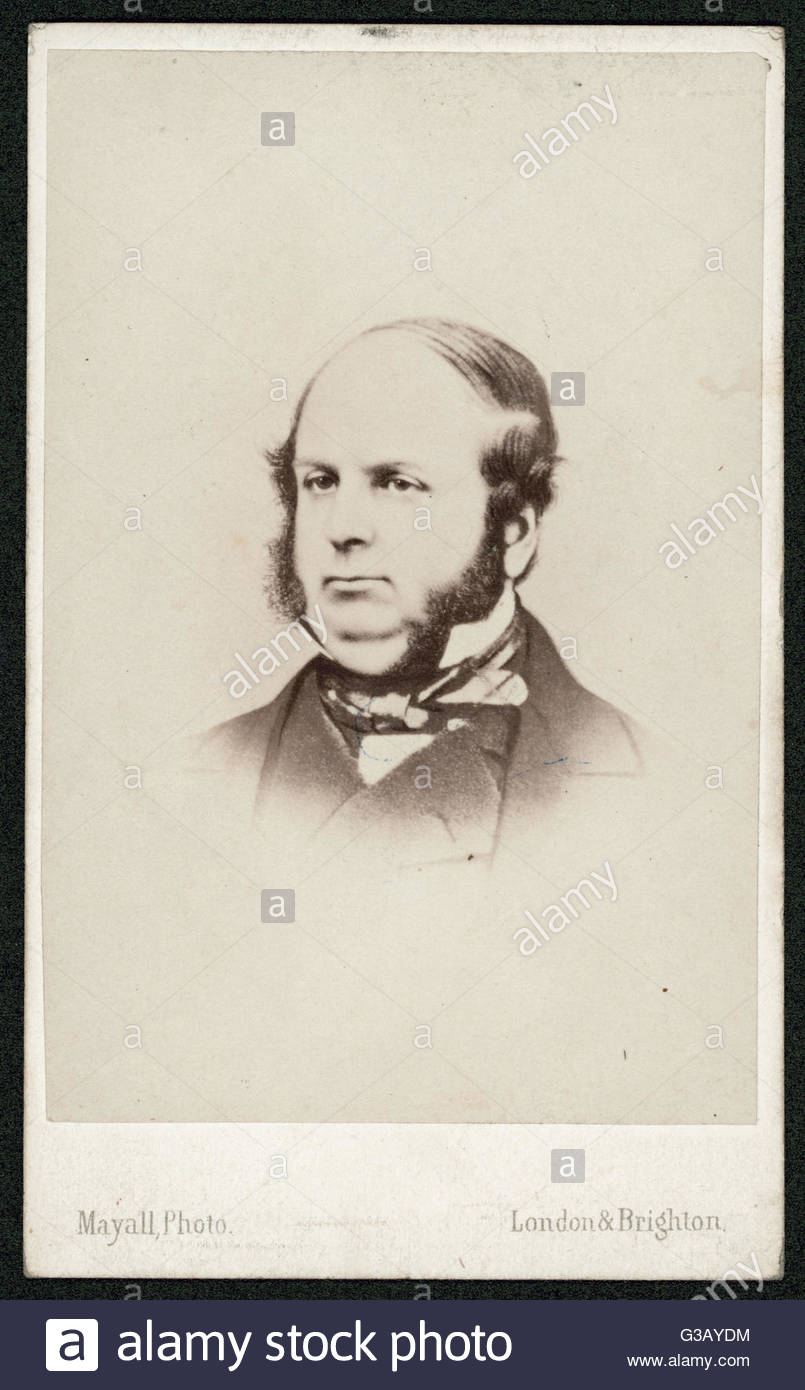

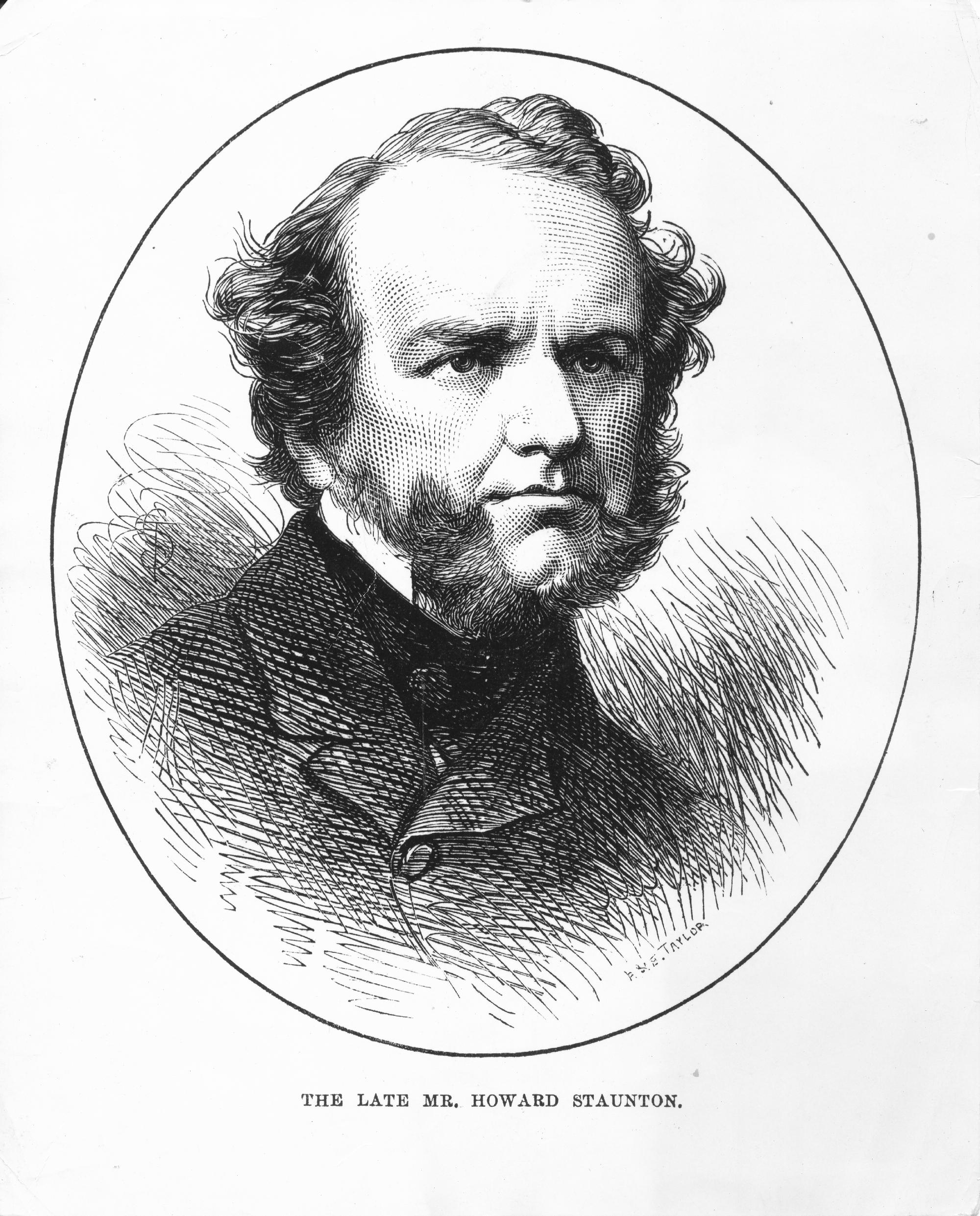

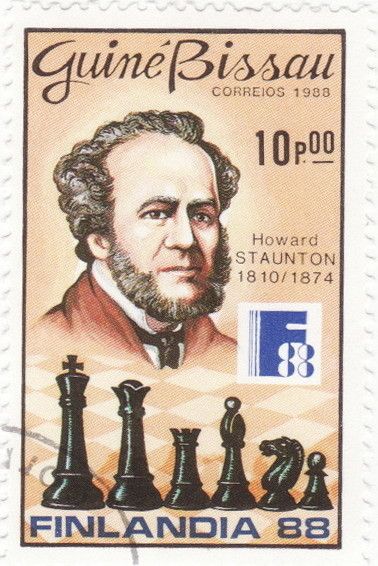

BCN remembers Howard Staunton (??-iv-1810 22-vi-1874)

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper and Whyld :

The world’s leading player in the 1840s, founder of a school of chess, promoter of the world’s first international chess tournament, chess columnist and author, Shakespearian scholar. Nothing is known for certain about Staunton’s life before 1836, when his name appears as a subscriber to Greenwood Walkers Selection of Games at Chess , actually played in London, by the late Alexander McDonnell Esq. He states that he was born in Westmorland in the spring of 1810, that his father’s name was William, that he acted with Edmund Kean, taking the part of Lorenzo in The Merchant of Venice, that he spent some time at Oxford (but not at the university) and came to London around 1836. Other sources suggest that as a young man he inherited a small legacy, married, and soon spent the money.

He is supposed to have been brought up by his mother, his father having left home or died. He never contradicted the suggestion that he was the natural son of the fifth Earl of Carlisle, a relationship that might account for his forename, for the Earl’s family name was Howard: but the story is almost certainly untrue, not least because in all probability Howard Staunton was not his real name. A contemporary, Charles Tomlinson (18O8- 97), writes: ‘Rumour . . . assigned a different name to our hero [Staunton] when he first appeared as an actor and next as a chess amateur.

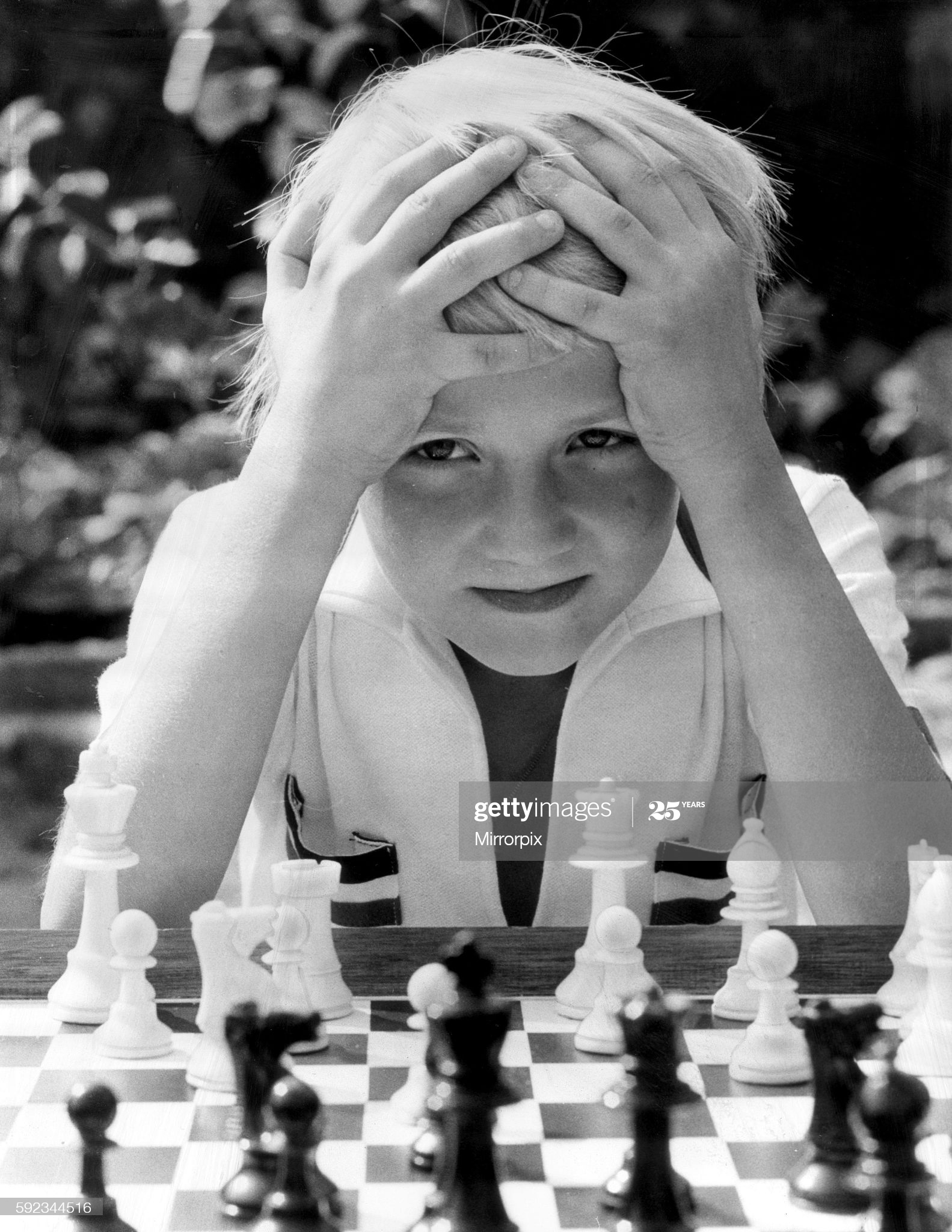

At the unusually late age of 26 Staunton became ambitious to succeed at chess; a keen patriot, his motivation may in part have sprung from a desire to avenge McDonnell’s defeat at the hands of a Frenchman. A rook player in 1836 (his own assessment), Staunton rose to the top in a mere seven years. In 1838 he played a long series of games with W. D. Evans and a match of 21 games with Alexandre in which he suffered ‘mortifying defeat’ during the early sittings; but he continued to study and to practise with great determination.

In 1840 he was strong enough to defeat H. W. Popert, a leading German player then resident in London. In the same year he began writing about the game. A short-lived column in the New Court Gazette began in May and ended in Dec. because, says G. Walker, there were ‘complaints of an overdose’. More successful was his work for the British Miscellany which in 1841 became the Chess Player’s Chronicle, England’s first successful chess magazine, edited by Staunton until 1854, Throughout 1842 Staunton played several hundred games with John Cochrane, then on leave from India, a

valuable experience for them both.

In 1843 the leading French player Saint-Amant visited London and defeated Staunton in a short contest -(+3 = 1—2), an event that attracted little attention; but later that year these two masters met in a historic encounter lasting from 14 Nov. to 20 Dec. This took place before large audiences in the famous Café de la Régence. Staunton’s decisive victory ( + 11 = 4—6) marked the end of French chess supremacy, an end that was sudden, complete, and long-lasting.

From then until the 1870s London became the world’s chess centre. In Oct. 1844 Staunton travelled to Paris for a return match, but before play could begin he became seriously ill with pneumonia and the match was cancelled.

Unwell for some months afterwards, he never fully recovered: his heart was permanently weakened. In Feb. 1845 he began the most important of his journalistic tasks, one that he continued until his death: in the Illustrated London News he conducted the world’s most influential chess column. Each week he dealt with a hundred or more letters; each week he published one or more problems, the best of the time. In 1845 he conceded odds of pawn and two moves and defeated several of his countrymen and in 1846 he won two matches playing level: Horwitz (+14=3 — 7) and Harrwitz (+ 7). In 1847 Staunton published his most famous chess book, the Chess Player’s Handbook, from which many generations of English-speaking players learned the rudiments of the game: the last of 21 editions was published in 1939. He published the Chess Players Companion in 1849.

In 1851 Staunton organized the world’s first international tournament, held in London. He also played in it, an unwise decision for one burdened with the chore of organization at the same time. After defeating Horwitz (+4=1—2) in the second round he lost to Anderssen, the eventual winner.

Moreover he was defeated by Williams, his erstwhile disciple, in the play-off for places. Later that year Staunton defeated Jaenlsch ( + 7=1 — 2) and scored +6 = 1—4 against Williams, but lost this match because he had conceded his opponent three

games’ start. In 1852 Staunton published The Chess Tournament, an excellent account of this first international gathering. Subsequently he unsuccessfully attempted to arrange a match with Anderssen, but for all practical purposes he retired from the game at this time.

Among his many chess activities Staunton had long sought standardization of the laws of chess and, as England’s representative, he crossed to Brussels in 1853 to discuss the laws with Lasa, Germany’s leading chess authority. Little progress was made at this time, but the laws adopted by FIDE in 1929 are substantially in accordance with Staunton’s views. This trip was also the occasion of an informal match, broken off when the score stood +5=3-4 in Lasa’s favour. Staunton took the match seriously, successfully requesting his English friends to send him their latest analyses of the opening.

Staunton had married in 1849 and, recognizing his new responsibilities, he now sought an occupation less hazardous than that of a chess-player. In 1856. putting to use his knowledge of Elizabethan and Shakespearian drama, he obtained a contract to prepare an annotated edition of Shakespeare’s plays. This was published in monthly instalments from Nov. 1857 to May 1860, a work that ‘combined commonsense with exhaustive research’. (In 1860 the monthly parts ready for binding in three volumes were reissued, in 1864 a four-volume reprint without illustrations was printed, and in 1978 the original version was published in one volume.) Staunton, who performed this task in a remarkably short period, was unable to accept a challenge from Morphy in 1858: his publishers would not release him from his contract. After the proposal for a match was abandoned Frederick Milnes Edge (c. 1830-82), a journalist seeking copy, stirred up a quarrel casting Staunton as the villain. Morphy unwisely signed some letters drafted by Edge, while Staunton, continuously importuned by Edge, was once driven to make a true but impolitely worded comment about Morphy. Generally however these two great masters behaved honourably, each holding the other in high regard; but Edge’s insinuations unfairly blackened Staunton’s reputation.

Subsequently Staunton wrote several books, among them Chess Praxis (1860) and the Great Schools of England (1865), revised with many additions in 1869. At the end of his life he was working on another chess book when, seized by a heart attack, he died in his library chair.

Staunton was no one’s pupil: what he learned about chess he learned by himself. For the most part he played the usual openings of his time but he introduced several positional concepts. Some of these had been touched upon by Philidor, others were his own: the use of the ranch mo for strategic ends, the development of flank openings specially suited to pawn play. He may be regarded as the precursor of the hypermodern movement, the Staunton system the precursor of the Reti opening. In his Chess Players Companion Staunton remarks that after 1 e4 e5 Black’s game is embarrassed from the start, a remark anticipating Breyer’s ideas about the opening by more than half a century, Fischer wrote in 1964: “Staunton was the most profound opening analyst of all time. He was more theorist than player but none the less he was the strongest player of his day. Playing over his games I discover that they are completely modern.

Where Morphy and Steinitz rejected the fianchetto. Staunton embraced it. In addition he understood all the positional concepts which

modern players hold so dear, and thus with Steinitz must be considered the first modern player.

Tall, erect, broad-shouldered, with a leonine head, Staunton stood out among his fellows, walking like a king’. He dressed elegantly, even ostentatiously, a taste derived perhaps from his

background as an actor. G. A. Macdonnell describes him: “… wearing a lavender zephyr outside his frock coat. His appearance was slightly gaudy, his vest being an embroidered satin, and his scarf gold-sprigged with a double pin thrust in, the heads of which were connected by a glittering chain . . .’ A great raconteur, an excellent mimic who could entertain by his portrayals of Edmund Kean, Thackeray, and other celebrities he had met, he liked to hold the stage, ‘caring for no man’s anecdote but his own’. He could neither understand nor tolerate the acceptance of mediocrity, the failure of others to give of their best.

A man of determined opinions, he expressed them pontifically, brooking little opposition. Always outspoken, he often behaved, writes Potter, ‘with gross unfairness towards those whom he disliked, or from whom he suffered defeat, or whom he imagined to stand between himself and the sun’; ‘nevertheless’, he continues, ‘there was nothing

weak about him and he had a backbone that was never curved with fear of anyone.’ Widely disliked, Staunton was widely admired, a choice that would have been his preference. Reminiscing in 1897, Charles Edward Ranken (1828-1905) wrote: “With great defects he had great virtues; there was nothing mean, cringing, or small in his nature, and, taking all in all, England never had a more worthy

chess representative than Howard Staunton.

R. D. Keene and R. N. Coles Howard Staunton the English World Chess Champion (1975) contains biography, 78 games, and 20 parts of games.

The Staunton Defence has remained a completely playable gambit versus the Dutch Defence :

Here is his Wikipedia entry

A curious article about Staunton

From British Chess Magazine, Volume CXIX (119, 1999), Number 11 (November), page 584 :

“English Heritage unveiled a blue plaque to Howard Staunton, arguably Britain’s greatest 19th century chess player, in London on September 28. The unveiling took place at 117 Landsdowne Road, London W11, and was performed by Barry Martin, secretary of the Staunton Society, on behalf of English Heritage. Staunton lived with his wife at 117 Lansdowne Road between 1871 and 1874. He died at 27 Elgin Crescent later that year. The weather was favourable and a good crowd (including several grandmasters) was able to enjoy proceedings. BBC television covered the event for their lunch-time and evening news programme.”