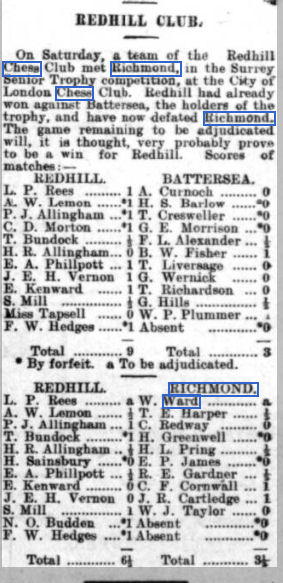

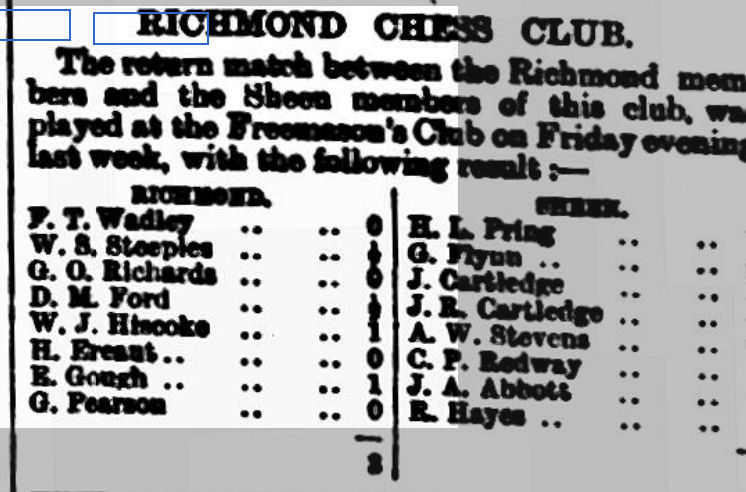

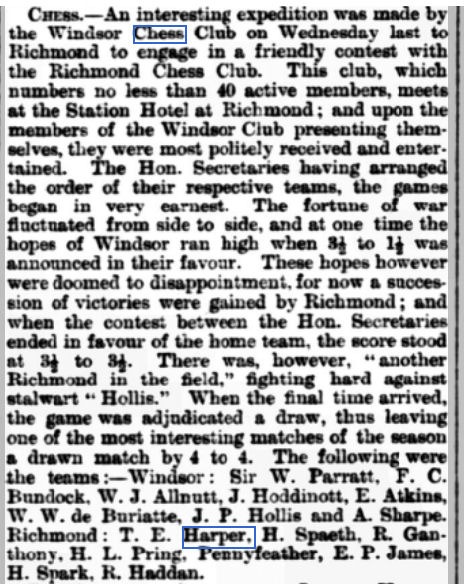

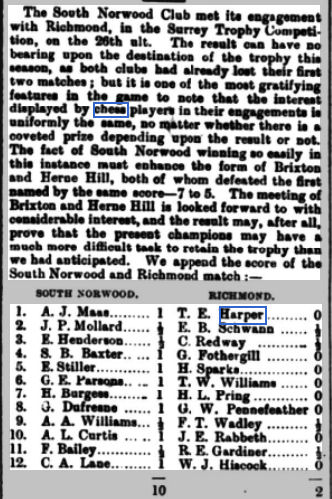

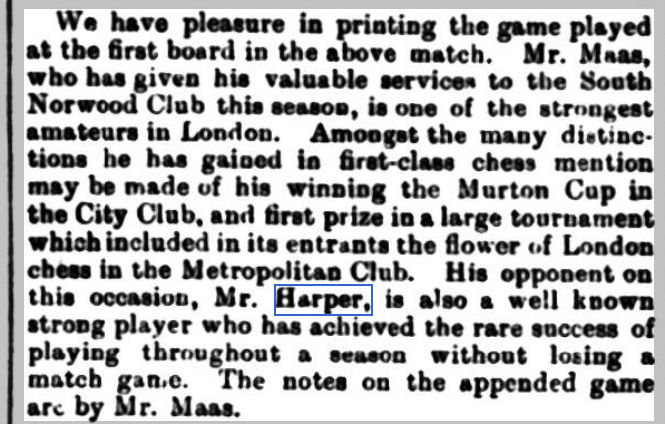

Last time we left William Ward in 1909, when he had just competed in his fourth British Championship. As it happens, it would be his last appearance (perhaps his legal work was more pressing) but he continued playing in the City of London Championship, as well as in county matches.

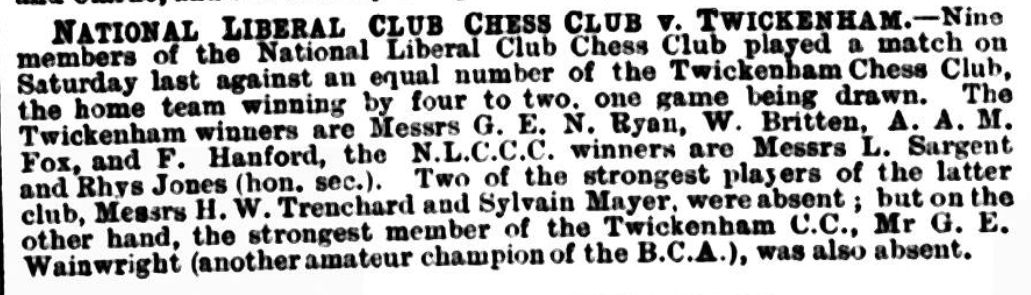

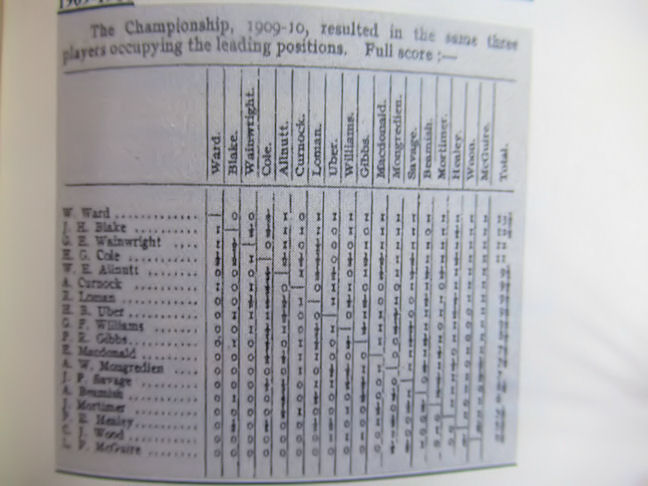

Here, as you can see, he was again successful in the 1909-10 competition, where the same three players filled the first three places as in the previous year.

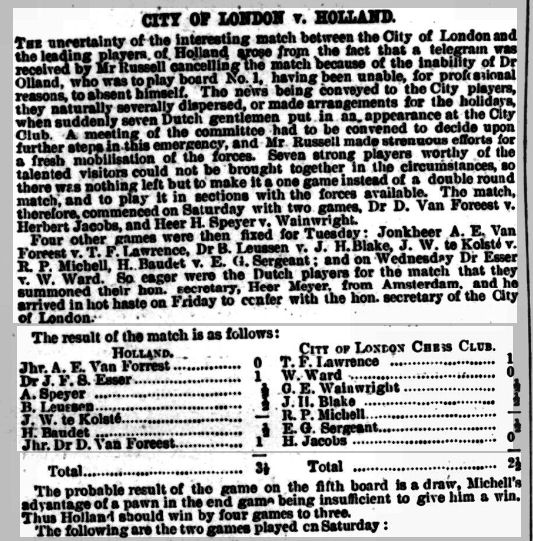

In March 1910 he was selected to take part in a match between the City of London club and a visiting team representing the Dutch Chess Federation. The administration of this event, seemed, from the report below, to have been somewhat chaotic.

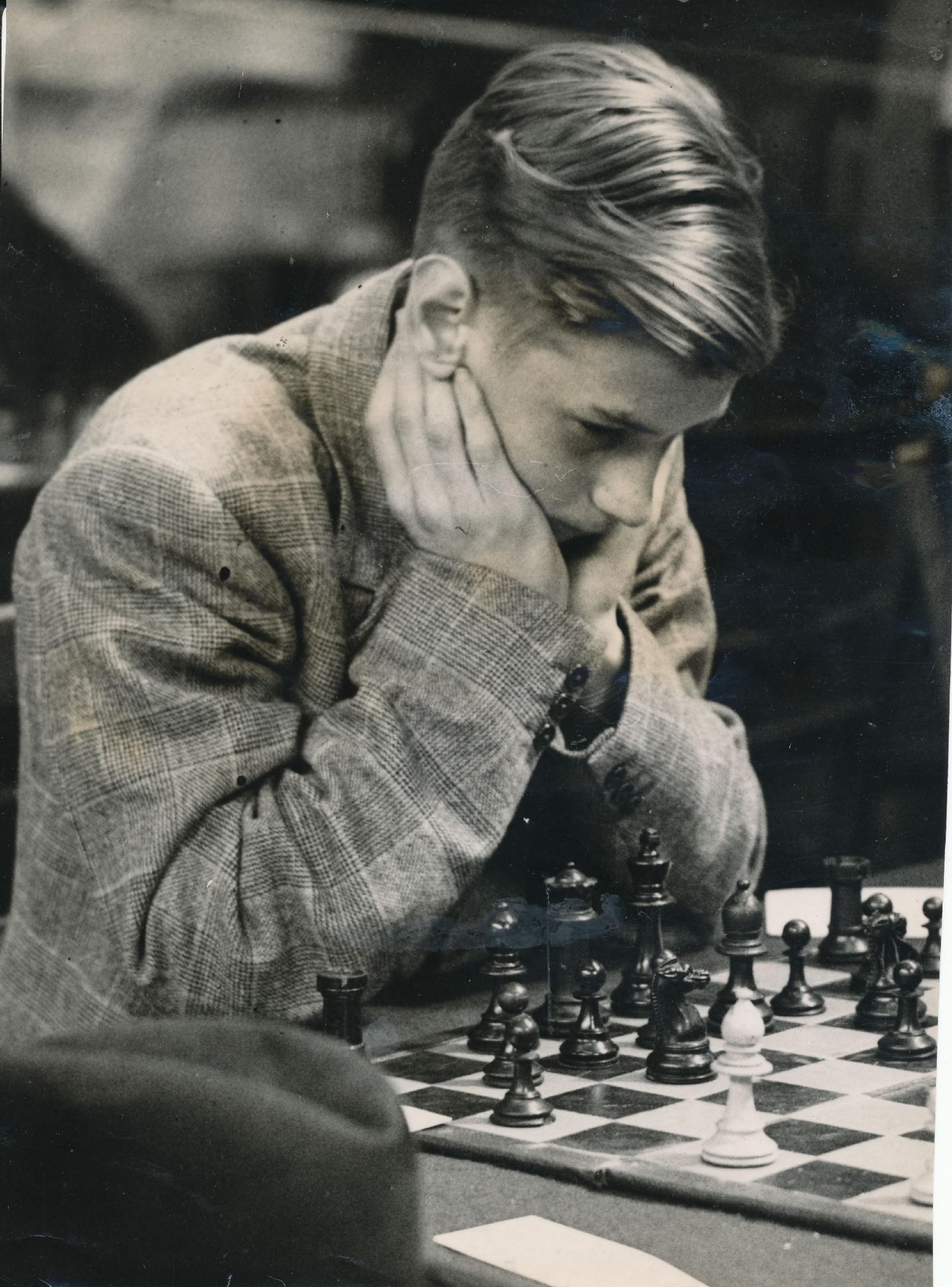

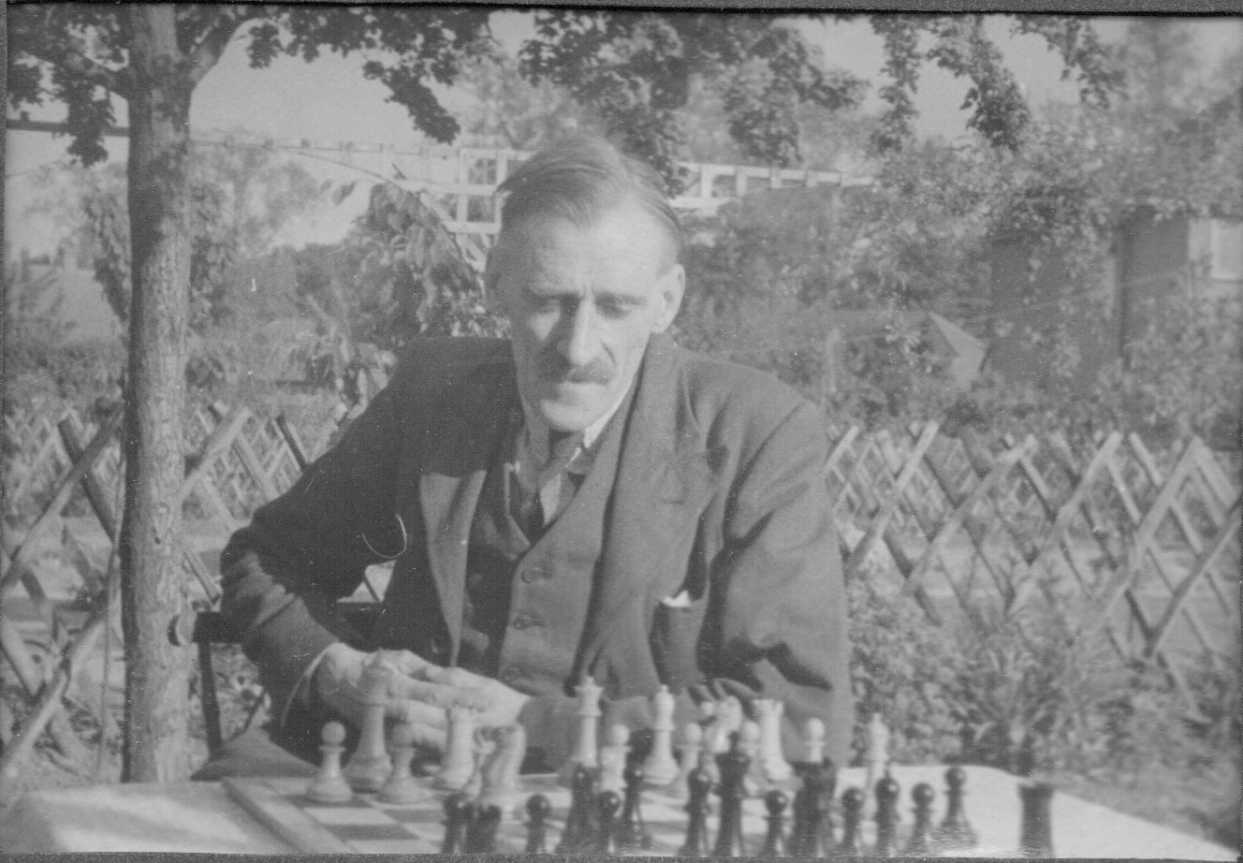

You might notice a familiar surname appearing twice in the Sutch team. Arnold van Foreest (his name spelt incorrectly above) is the great great grandfather of Jorden (winner of the 2021 Tata Steel Masters), Lucas and Machteld van Foreest. Dirk was his brother, and had a remarkably long chess career, stretching from the 1884 Dutch Championship to a match against fellow octogenarian Jacques Mieses in 1949.

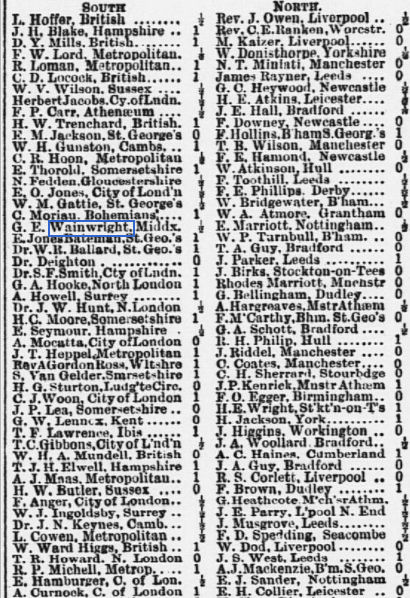

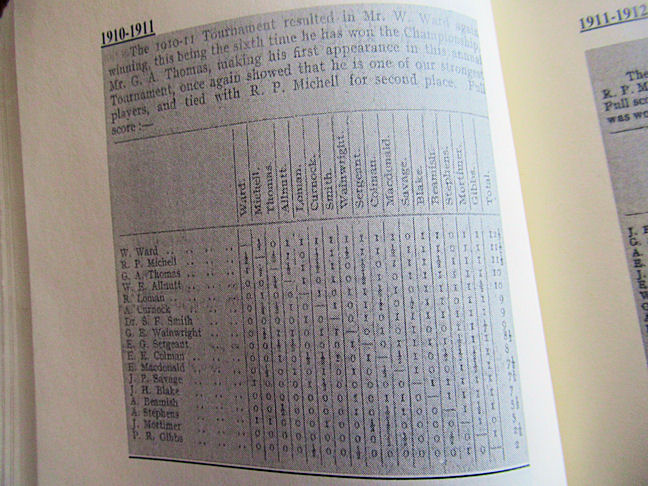

William Ward took the City of London title for the sixth time in 1910-11. This time he finished ahead of Reginald Pryce Michell, a strong player with Kingston connections, and the young George Alan Thomas, yet to inherit his baronetcy. (I’m not certain about the accuracy of this table. I have a game in which Ward allegedly beat A Stephens, but here, the result is given as a loss for him.)

In this game against the veteran James Mortimer, who had played Morphy many decades earlier, he clamped down on his opponent’s backward e-pawn with logical and determined play before striking tactically.

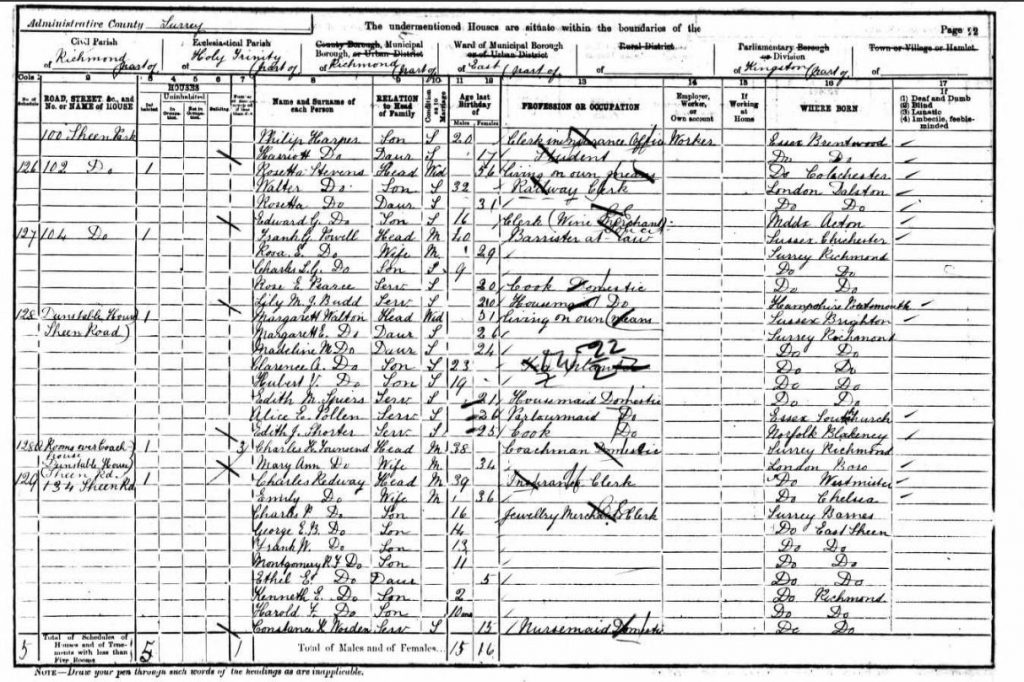

By now it was 2 April 1911, time for the census enumerator to call again. He found William living on his own in a single room in 3 Raymond Buildings, Gray’s Inn: he had a bachelor pad within his legal chambers. (As it happens, this is somewhere I used to know very well back in the 1970s: I’d pass it regularly when walking from my office to Foyle’s to browse the latest chess books.)

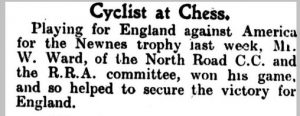

This snippet from Cycling (26 April 1911) reveals another side of William Ward. The North Road Cycling Club, founded in 1885 and today based in Hertford, claims to be one of the oldest in the country.

Entirely coincidentally, a photograph on the same page pictures a group of cyclists welcoming the winner of the Banks, Insurance and Stock Exchange Walk, JH van Meurs, who, when he wasn’t walking and dealing in grain, played an important part in both London and national chess administration over many decades. Two prominent figures in the chess world on the same page of a cycling magazine!

In 1911 the British Chess Federation decided they needed someone to rewrite the Laws of Chess. Given his legal background, could there have been anyone better that William Ward for the job?

Well, quite possibly. It didn’t go well. The Rev E E Cunnington, who had written the previous version, and was perhaps feeling aggrieved about the rewrite anyway, made his views very clear in The Chess Amateur.

Mr. W. Ward has been guilty of two offences: discreditable conduct in taking without leave or acknowledgement the work of other men; defacing their work by his clumsy, muddling, alterations.

The proper title of Mr. Ward’s work is “The British Chess Code mutilated and marred by W. Ward”.

It sounds like the clergyman was accusing the lawyer of plagiarism. Could you imagine any other leading chess player taking without leave or acknowledgement the work of other men? Well, perhaps you could!

The whole affair, including a copy of the offending Laws, is documented by Edward Winter here. It seems to me that the BCF would have been better appointing someone who could write plain English rather than writing in legalese!

Ward didn’t take part in the 1911-12 City of London Club Championship, but returned for their Diamond Jubilee Championship the following season.

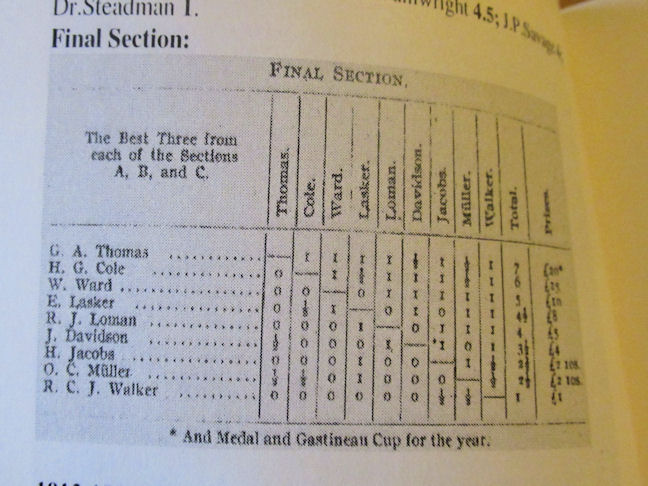

There was a large entry, split into three groups, with the top three in each group qualifying for the final pool.

Ward finished in third place, behind George Alan Thomas and Harold Godfrey Cole, winning £10 for his pains, along with a brilliancy prize of five guineas for the game below. The fourth placed player was Edward, who was living in London at the time, not his distant cousin Emanuel.

In this game, facing what was at the time his favourite opening, Ward displayed positional acumen in playing against his opponent’s isolated d-pawn, and then tactical skill in switching to a kingside attack.

This was to be William Ward’s last appearance in the City of London Championship, although the event continued through the First World War. Perhaps his legal business left him little time for chess on weekday evenings. He did continue to play in county matches, however, which also continued in spite of the hostilities.

This game comes from a county match from 1919. Ward was awarded the full point by the adjudicator.

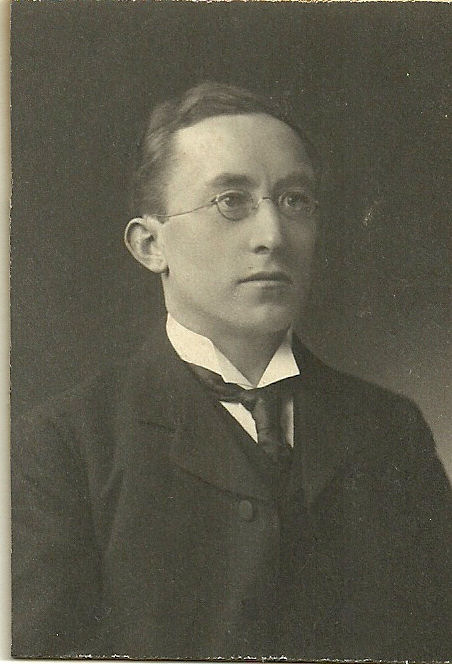

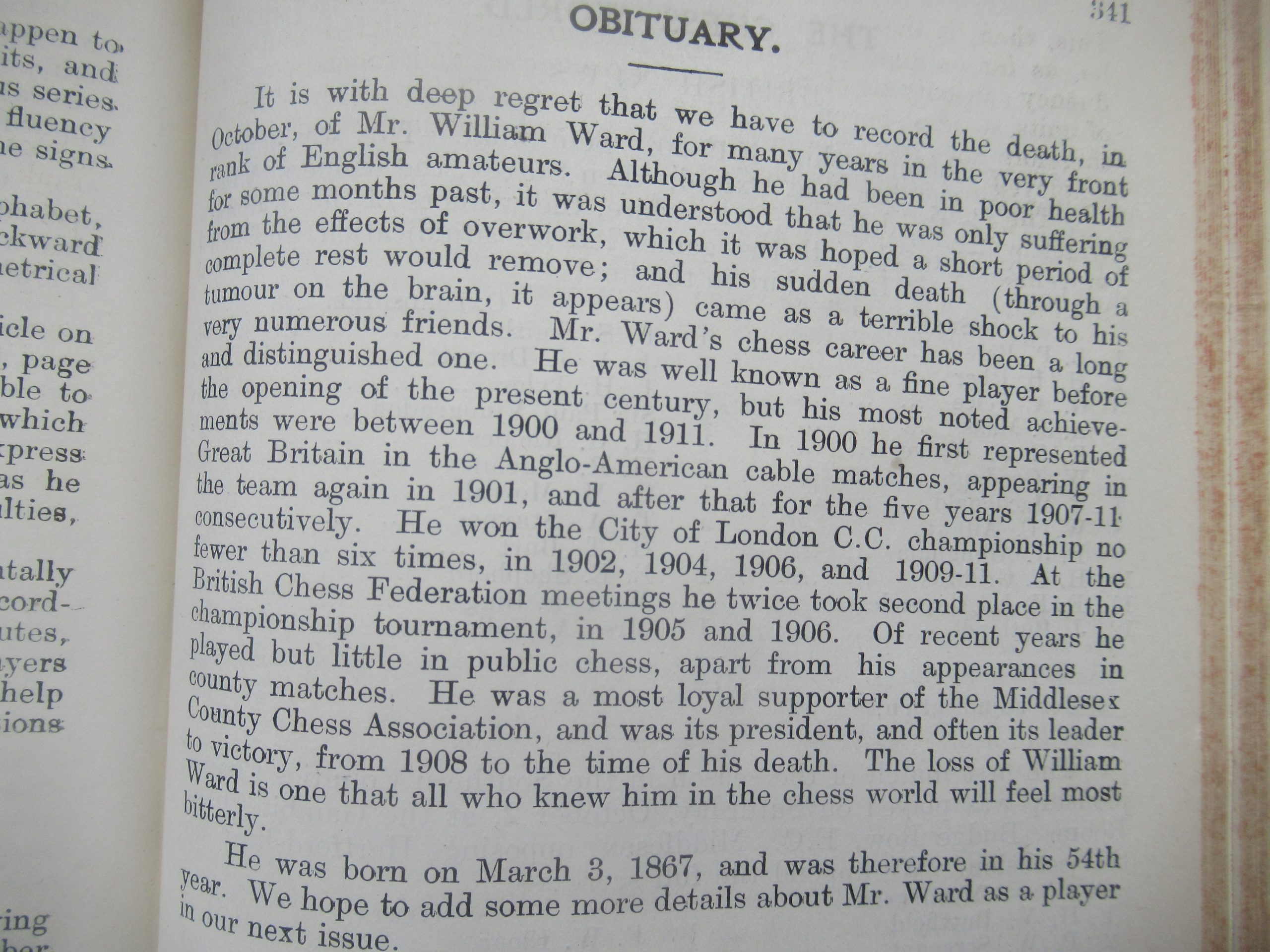

As it turned out, this was to be one of William Ward’s last games. A few months later he was struck down by illness – which sadly turned out to be a brain tumour. He died in hospital on 16 October 1920 at the age of 53. Here’s his obituary from the British Chess Magazine.

We didn’t get very much more the following month: just the Davidson game given above.

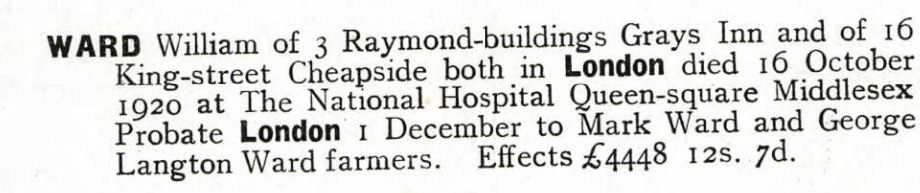

Here’s his probate record.

16 King Street would also have been a work address, about 25 minutes walk away from Raymond Buildings along Holborn, passing the Old Bailey and St Paul’s Cathedral on the way. His effects would be worth about £130,000 now. Probate was granted to his two brothers.

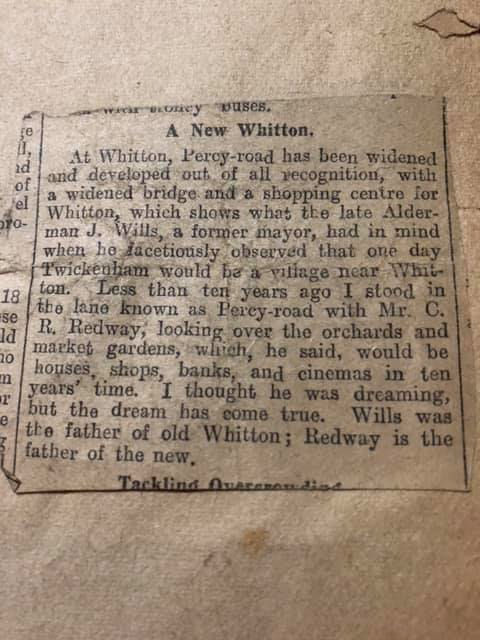

Tragically, William’s father would have to bury two of his sons. Mark died in February 1922, leaving a wife and four children, the oldest of whom also died just a few hours later. William senior lived on until 1926, while his youngest son George, who married and had one son, died in Harpenden in 1945. In the same town, at about the same time, Howard James, from Leicester, serving in the Royal Artillery, was introduced to Betty Smith, whose family had advised her to move from Teddington to avoid the bombs, by a mutual friend. But that’s another story.

And that concludes my investigation into the life of William Ward, unjustly forgotten today. His best games are, I think pretty impressive for their time, and, had he started earlier and chosen the life of a professional chess player, he had the natural ability to scale the heights.

Next time I play chess at Richmond Chess Club, I’ll think of William and hope his talent will inspire my play.

Join me again soon to meet some more Richmond Chess Club members from the first years of the 20th century.

Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

BritBase

EdoChess (Ward’s page here)

British Chess Magazine

The City of London Chess Club Championship (Roger Leslie Paige): thanks to Paul McKeown for the book.