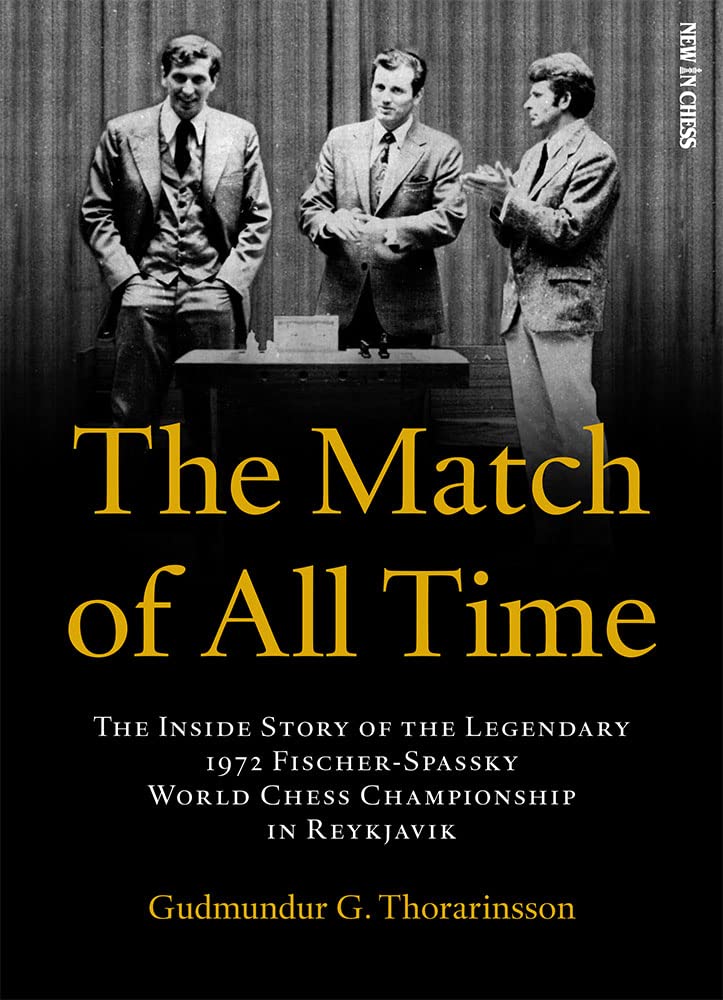

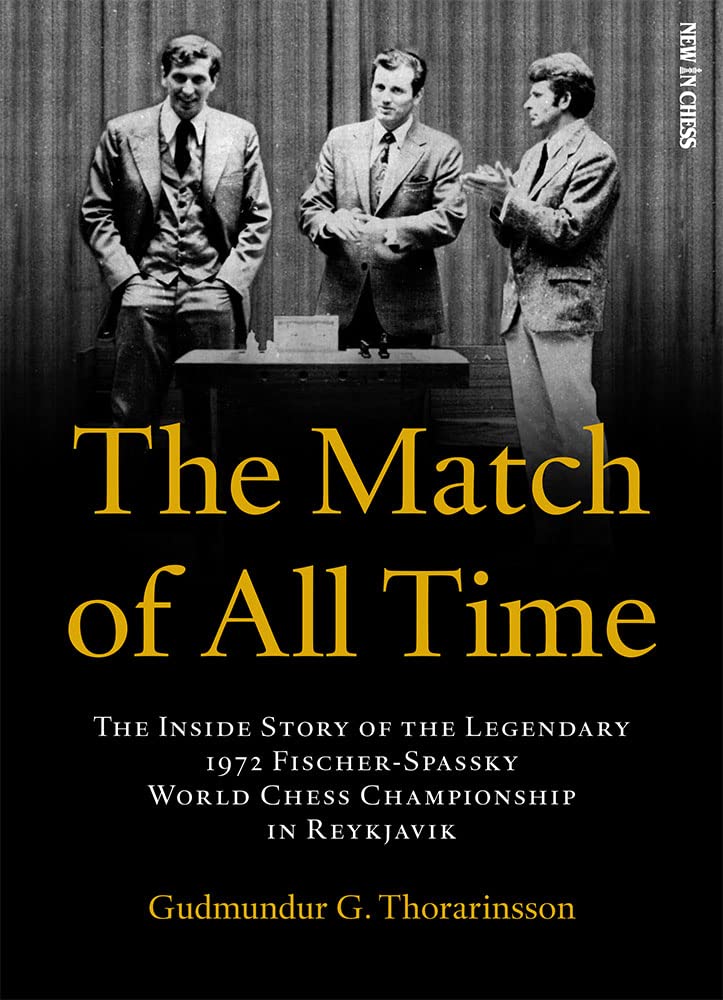

From the publisher:

“When the Icelandic Chess Federation made a bid to host the 1972 world title match between Soviet icon Boris Spassky and American challenger Bobby Fischer, many Icelanders were rightly shaking their heads in disbelief. How could their small island country in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean with a population of less than 300 thousand people stage such a prestigious event in the first place?

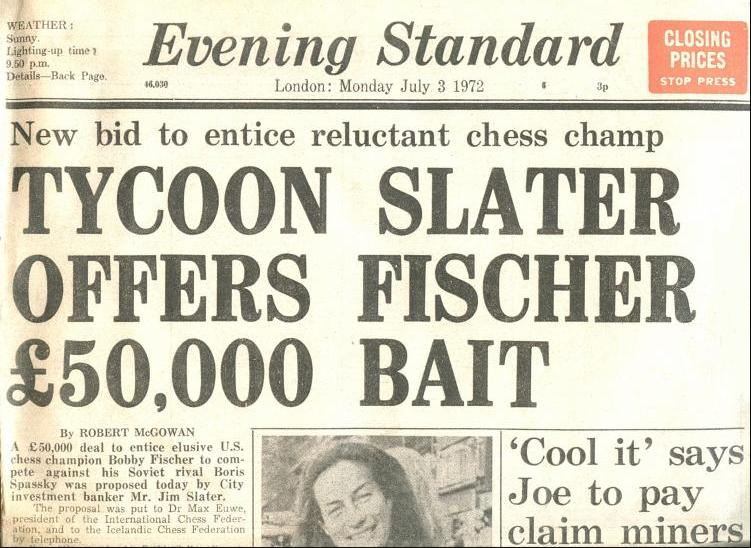

“Undeterred and naively optimistic, the young President of the Icelandic Chess Federation, Gudmundur Thorarinsson, set to work and to everyone’s astonishment theirs was the winning bid. But that was only the beginning of one of the most amazing stories in chess history… Bobby Fischer’s demands and whims constantly jeopardised the match. First the American chose not to board his plane in New York, and then he came late for the first game. That game he lost after a silly blunder and the second game he lost because he didn’t turn up in a fight about noisy cameras. But next he won the third game, that was played in a back room, and the rest…. is history.

“Fifty years on, Gudmundur Thorarinsson has written a tell-all book about ‘The Match of the Century’, crammed with behind-the-scenes stories and improbable twists and turns. Reading his gripping account of probably the most iconic sports contest during the Cold War, you will understand why he prefers to call it ‘The Match of All Time’. And why reliving this most unlikely adventure he comes to the conclusion: ‘It was not possible to organise this match, nor was it possible to rescue it…but still it was done!'”

“Gudmundur Thorarinsson is a chess organizer and businessman from Iceland. In 1972, as the chairman of the Icelandic Chess Federation he organized the Match of All Time, the World Championship Match between the Russian incumbent champion Boris Spassky and the American challenger Bobby Fischer.”

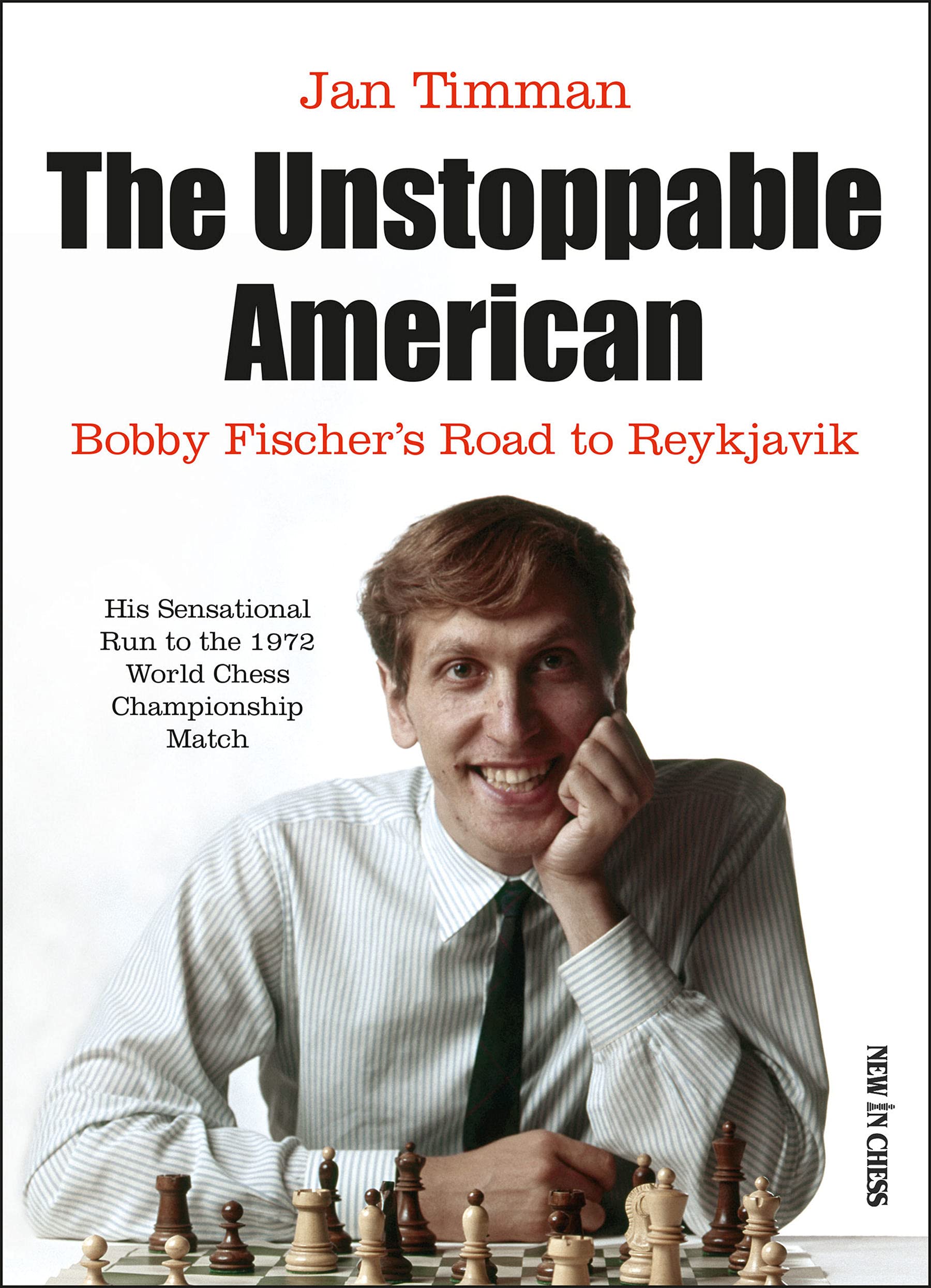

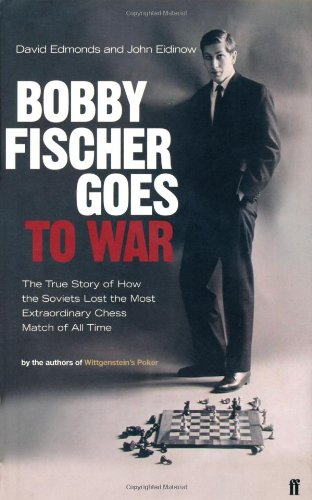

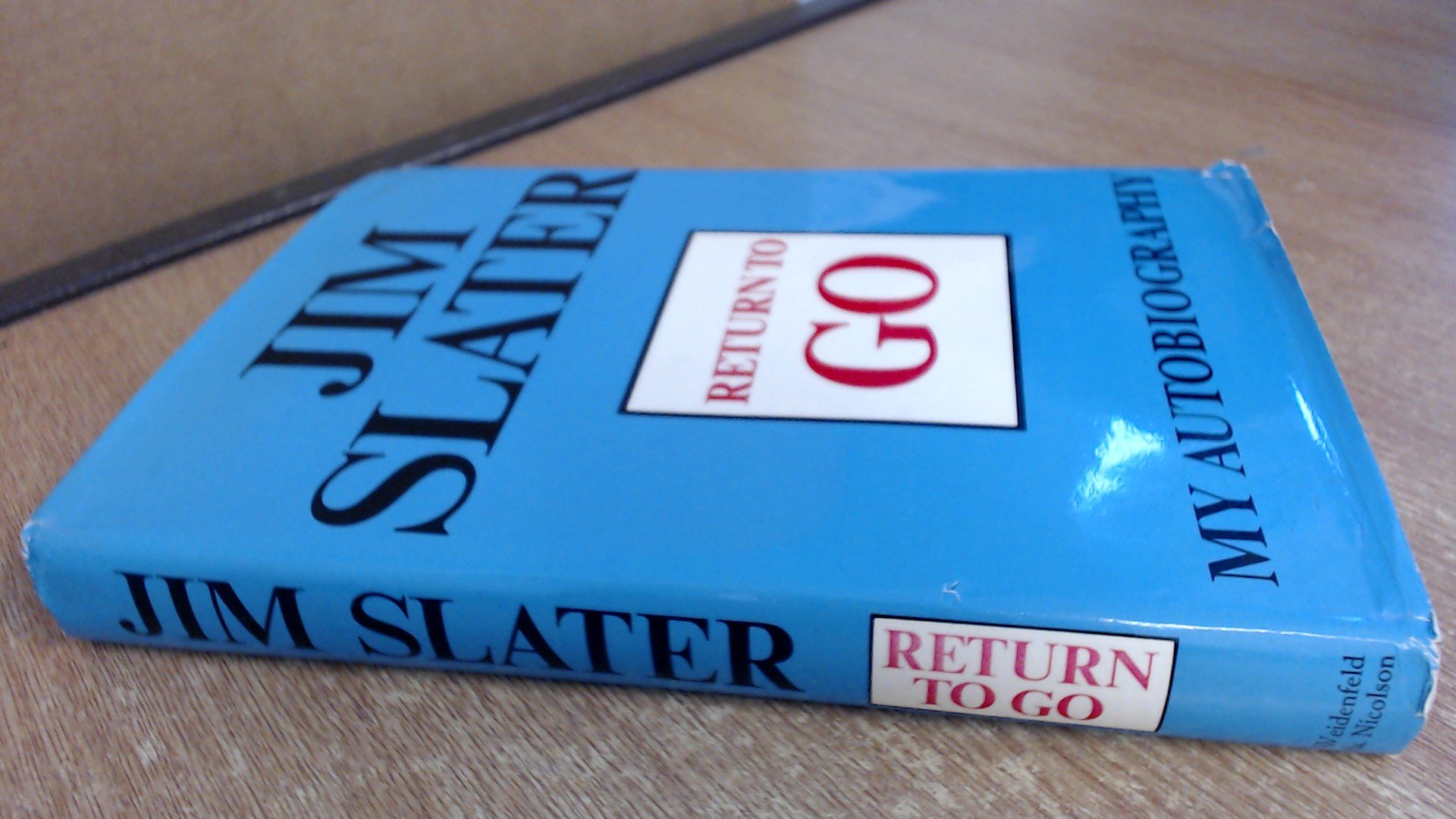

Half a century on from the legendary Fischer – Spassky World Championship match, and still the books keep on coming.

From Chapter 1 (Prologue):

Why write another book about the World Chess Championship match in 1972? Approximately 140 books have been published about the match already, plus films, TV and radio programs, newspapers and magazine articles. To add another book to this list seemed too much to me. But many people have been encouraging me to write about the match, people working for radio and television, chess players and friends. But many have simply said: ‘We still do not have a book written by someone who was working behind the scenes, where the bombs were falling.

One thing is certain: a long time ago this match acquired a life of its own. Nowadays people tend to look at the course of events from a different perspective. Looking at the match from afar enables the observer to put the whole saga into another context, broadening the horizon, so to speak. It may be true that the viewpoint and experiences of those of us who were on the frontline during the planning and execution of the event have not been widely documented. Those who wrote about the match in the following months, or even years after it happened, did so mostly by annotating the games, explaining the battle from the perspective of the chess players or the audience.

If you’re looking for the games of the match you’ll be disappointed: but of course they are readily available elsewhere.

What you have instead is a source document telling the story of what was going on in the background, written by someone who was there and very closely involved at the time.

The book is designed to be interesting to the general reader as well as the chess specialist. Chapter 2, therefore, looks at the origins of chess, including a contribution from GM Fridrik Olafsson, an expert in this field, and, specifically, the early history of chess in Iceland.

Chapter 3 relates the history of the world chess championship prior to Spassky, starting with Stamma and Philidor, and taking us as far as Petrosian. There is little here that will be new to readers familiar with chess history.

Chapter 4, on the prelude to the 1972 match, is where things start getting interesting. We read about Fischer’s wins in his Candidates Matches against Taimanov, Larsen and Petrosian before being introduced to the two protagonists, with background information about their family, upbringing and chess career. Then the bidding process for the match venue is discussed, with Iceland, a small country in the Atlantic Ocean, but with a proud chess history, unexpectedly being selected.

The author of this book had, as a young man, been appointed President of the Icelandic Chess Federation in 1969. He had been proposed in his absence by his brother and not wanting to cause embarrassment, felt he had no choice but to accept. As a result, he found himself in the middle of negotiations which would have a dramatic effect on the history of chess.

Chapter 5, the longest in the book, covers the match itself in fascinating and engrossing detail. Everyone who was interested in chess at the time will have vivid memories of Fischer’s demands and conditions, and of the problems and arguments these caused. Thorarinsson was at the heart of everything that was happening, and it was to no small extent due to his diplomatic skills, often described here in a self-deprecating way, that the match eventually started and, more or less successfully, concluded with Bobby as the new World Champion. There’s a lot of documentary material here which will be new to many readers.

Chapter 6 describes the aftermath of the match. Fischer’s life over the next three and a half decades is related, including his return match with Spassky in 1992. Bobby spent the last few years of his life in Iceland, and Thorarinsson was again very much involved with expediting his journey from a Japanese detention centre, and with helping him settle in for what would be his rather sad endgame.

This and the final section, the author’s tribute to his friend, which he delivered at Fischer’s memorial service, are both intensely moving.

If you’re looking for chess moves, this won’t be the book for you. But if you want to know more about Fischer, and about the background to the 1972 match, it will be an essential purchase.

The book is, like everything from this publisher, beautifully produced and copiously illustrated with photographs and cartoons. There are many entertaining and enlightening anecdotes to keep you amused as well. It’s a great story, reminiscent of a Greek tragedy, and well told here from the author’s unique perspective. Whether or not you’re familiar with what happened half a century ago, you’ll find it a gripping read.

Do bear in mind, though, that while it may be an important source document for future historians (and we really need a fully sourced and referenced biography of Fischer) it’s a memoir with its fair share of uncertainty and speculation. You read that ‘Harry Golombek states in one of his books…’: yes, but which one? Or, to take another example, ‘According to some sources…’. Which ones?

I have a few other issues, just as I do with many New in Chess books, essentially coming down to the fact that it could have benefitted from a firmer editorial hand and a final read-through from a native English speaker. There are odd words and sentences that are not quite idiomatic. There’s also a certain amount of repetition (Fischer’s parentage is discussed on page 82, and again on pages 90-92) and one or two places where I felt continuity might have been improved.

Nevertheless, this book is essential reading for anyone with an interest in Fischer as a person, or in the 1972 Fischer – Spassky match. If the subject matter appeals to you, and, if you have any interest at all in chess culture and history, it undoubtedly will, don’t hesitate.

You’ll find pricing and other details here and sample pages here.

Richard James, Twickenham 26th December 2022

Book Details:

- Softcover: 224 pages

- Publisher: New In Chess (30 Jun. 2022)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9493257479

- ISBN-13:978-9493257474

- Product Dimensions: 17.22 x 1.52 x 23.65 cm

Official web site of New in Chess