It’s time to continue the story of Richmond Chess Club through the 1890s.

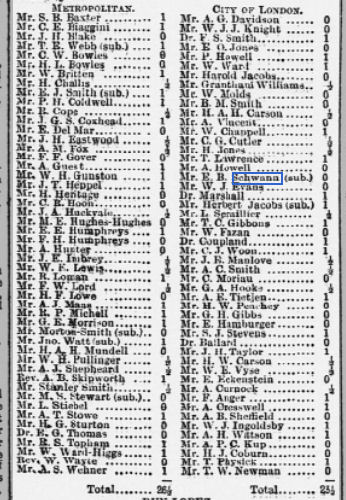

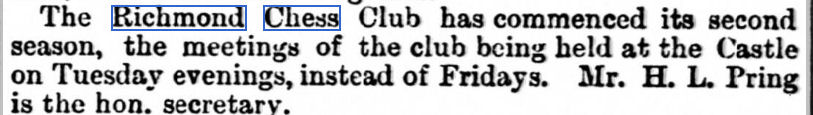

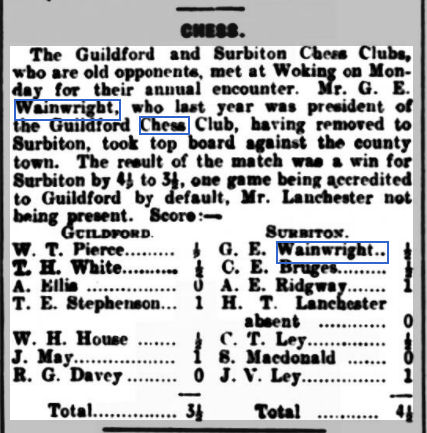

The club, as we’ve seen, was young and ambitious, and decided to enter the Beaumont Cup, run by the Surrey County Chess Association.

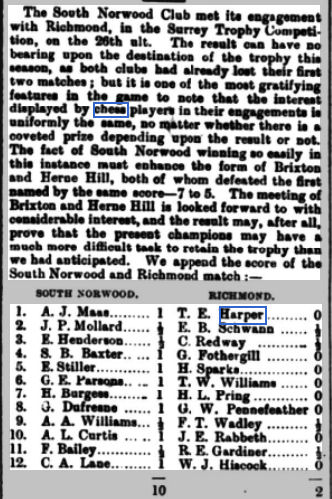

The Surrey League (except that it never seems to be called that) started in the 1883-84 season. It seems like only a few matches were played, probably on a knock-out basis, and taking place at central London venues rather than club venues.

By the 1895-96 season there was a demand for a second competition for less strong clubs, and a trophy named the Beaumont Cup was presented by the county President, Captain Alex Beaumont. The second division of the Surrey League is still, a century and a quarter later, the Beaumont Cup.

Some more information:

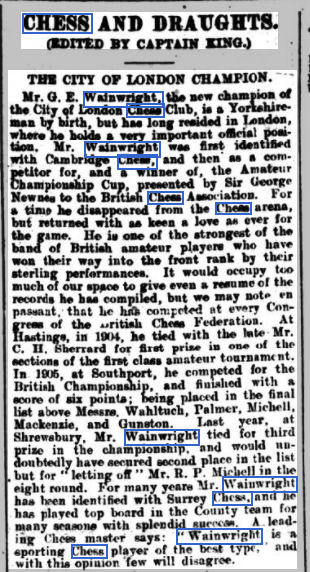

Beaumont, Alexander ‘Alex’ Spink 1843-4 Sep 1913 England, Manchester Deansgate – Kent, Beckenham amateur musician, 1872 captain of the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers, 21 Feb 1874 in Pembroke he was tried and acquitted for attempt to commit sodomy, 20 Sep 1910 made Freeman of the City of London in the presence of musicians, at time of death residing at Crossland, 28 Southend Road in Beckenham; son of Colonel Richard Henry John Beaumont; 24 Jan 1872 at Christ Church in London Paddington he married the widow Caroline Savage (Marlborough 1826-13 Apr 1907 Croydon), daughter of baronet Sir Erasmus Griffies-Williams. (Source: http://composers-classical-music.com/b/BeaumontAlexanderSpink.htm)

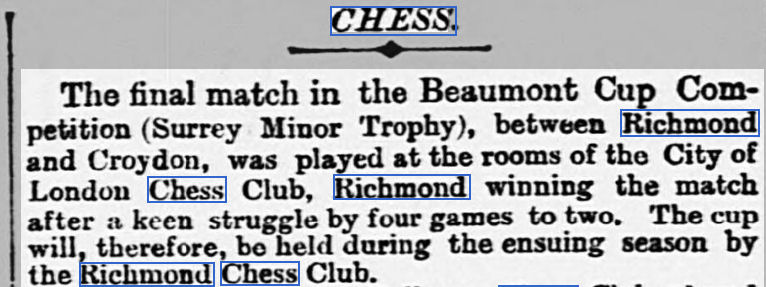

Here’s what happened in the second year of the Beaumont Cup’s existence.

Well played, Richmond! Sadly I don’t at present have a record of the names of the players in this historic match.

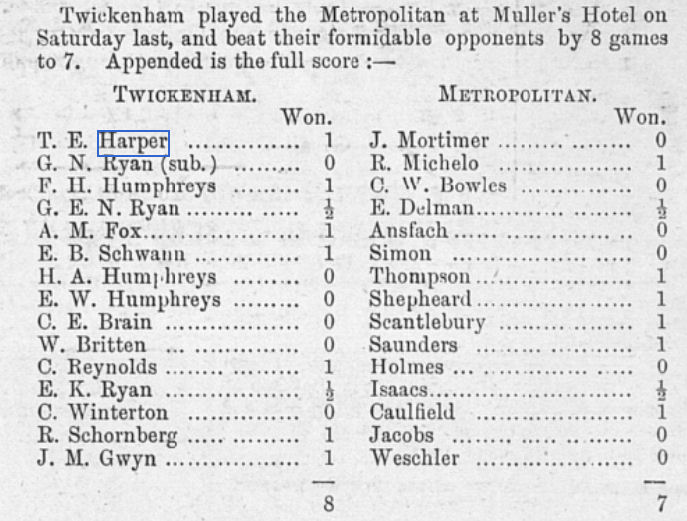

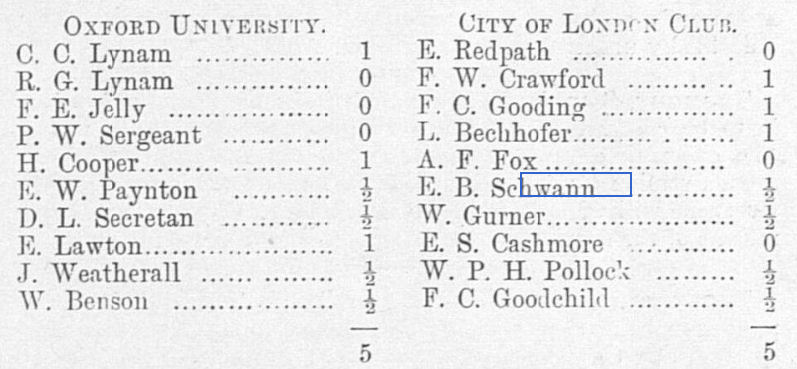

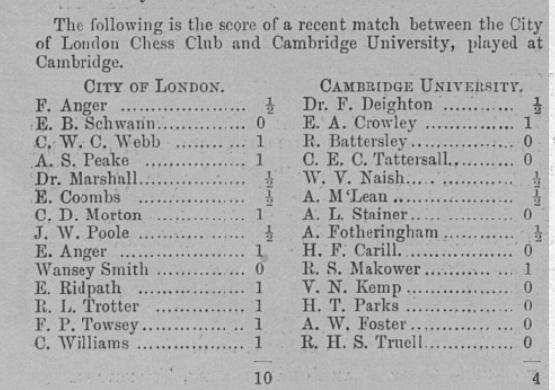

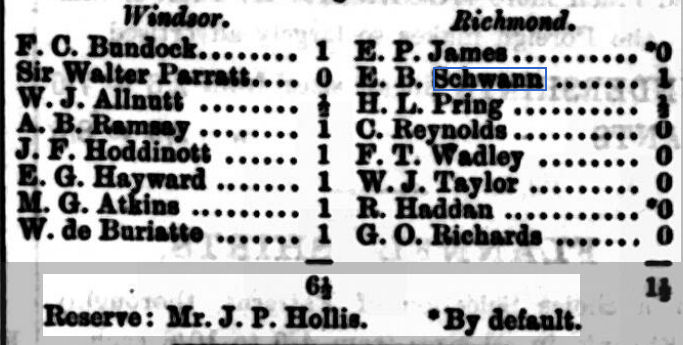

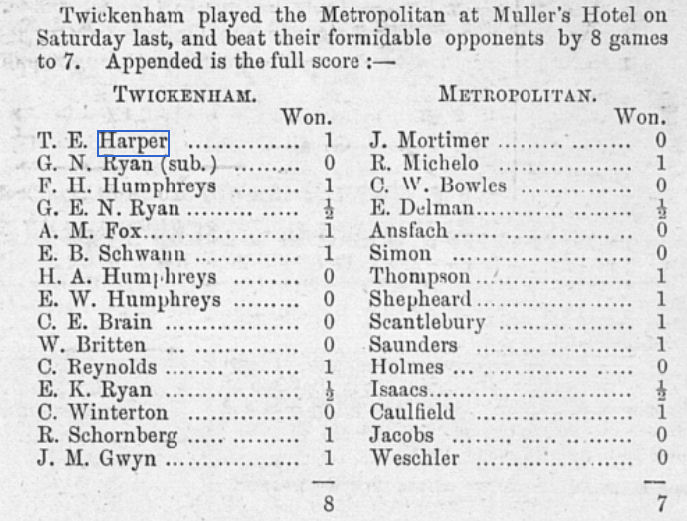

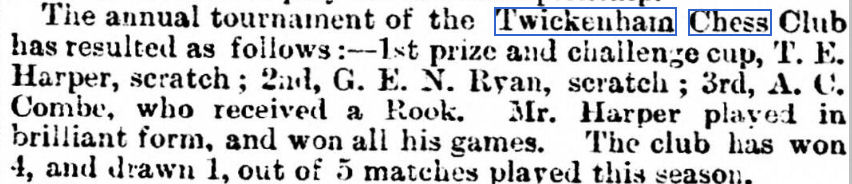

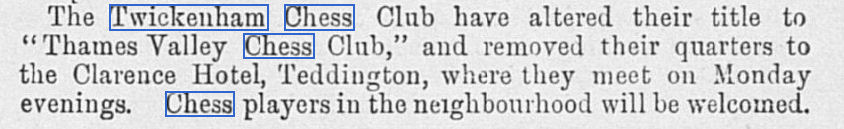

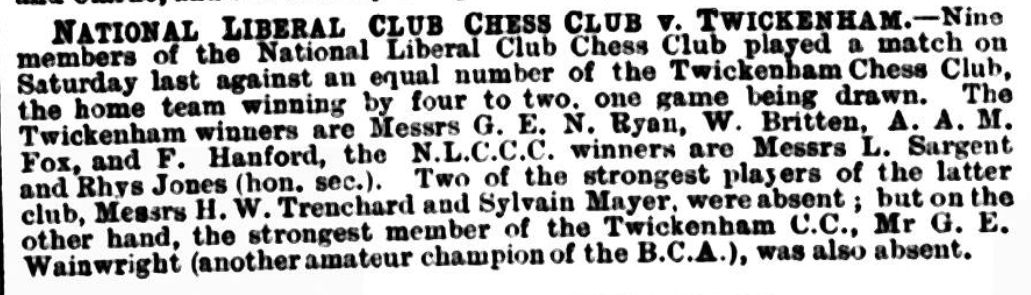

The club also continued to play friendly matches. As we’ve already seen, they played regular home and away matches against Windsor and, in this period, narrow defeats against both Thames Valley (formerly Twickenham) and West London were recorded.

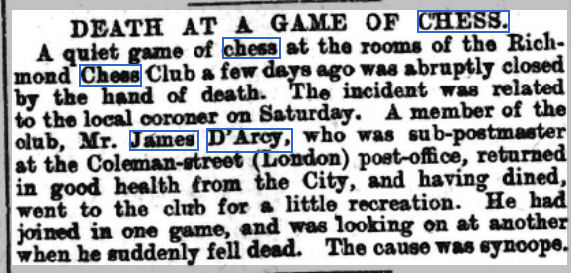

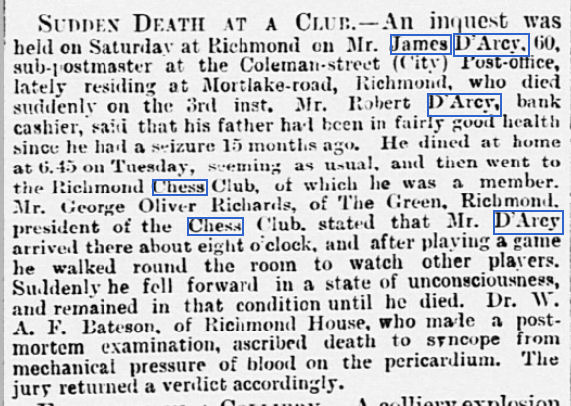

And then, in April 1900, Richmond Chess Club hit the headlines across the country for a tragic reason. Here are a couple of examples.

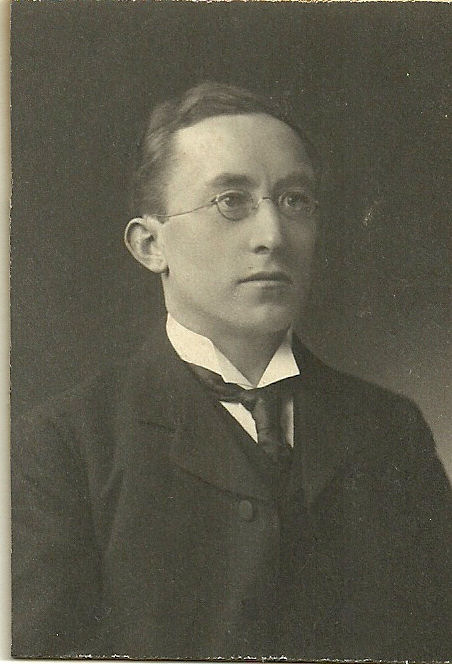

Who was the unfortunate (or perhaps fortunate to have died suddenly and painlessly doing something he enjoyed) James D’Arcy? It appears he was just a social player as I haven’t yet been able to find any information about him competing in matches or solving problems. Sub-postmaster sounds like a relatively humble occupation (unlike, for instance, club president George Oliver Richards, who was a dentist), but can we discover more about him?

His name is variously spelt D’Arcy, Darcy and Darcey in records, and most of the family trees he’s on give incorrect parentage, all copied from each other.

James’s birth was registered in the first quarter of 1840 in Boston, Lincolnshire: his parents, it seems, were John Darcey a farmer from the village of Wigtoft, between Boston and Spalding, and Elizabeth Brackenbury, although the 1841 census gives her name as Jane.

Sadly James senior died in 1847 and Elizabeth married Thomas Millhouse, a cottager (no, not THAT sort of cottager: just someone who owned a cottage and a small amount of land). By 1851 Thomas and Elizabeth had started their own family as well as bringing up James’s three younger siblings, while James himself was living in the nearby village of Swineshead with his grandparents James, an innkeeper, and Eleanor Brackenbury.

I haven’t yet been able to find him in the 1861 census but at some point he moved to London where, in 1866, he married Jemima Bond in Greenwich. The 1871 census located them in Hackney with their first child, a son named Robert. James had found employment as a solicitor’s clerk. He must have been doing pretty well for himself as the family residence was a fairly large 4 storey house. They were able to afford a servant, although having three boarders (all young men with clerical jobs) would have helped financially.

By 1881 they’d moved down the road to Islington, now with four children (Robert had been joined by Annie, Kate and Arthur), a servant, and a visitor, perhaps boarding there, David Reid, who was an East India Merchant born in New Brunswick. James’s job was now a Law Stationer.

Ten years on, and they’d moved to a different address in North London, not all that far from Hampstead Heath, and young Alfred had joined the family. James was still a Law Stationer, David Reid was still boarding there, and they still employed a servant. He might have come from a fairly modest family background in a small Lincolnshire village, but he’d prospered in London: something quite typical for the times, I think.

At some point in the 1890s, then, James and his family moved to 9 Mortlake Road, Kew and changed his job to that of a sub-postmaster. 9 Mortlake Road was, and still is, a large and impressive house near Kew Green: being a sub-postmaster must have paid well. The 1901 census records Jemima and all 5 of her surviving children (they had lost three children in infancy), along with Kate’s husband Maurice White and a servant. Maurice had been at Harrow with Winston Churchill, became a journalist and publisher, and later a picture dealer, being declared bankrupt on at least two occasions.

By 1911 Jemima had moved round the corner to Ennerdale Road, very convenient for Kew Gardens. The only one of her children at home was Annie, whose husband, Aubrey O’Brien was on leave from his job: he was a Major in the Indian Army in civil employ in the Punjab Commission as Deputy Commissioner. Their two young sons, Turlough and Edward, were there, along with three servants. Jemima died in Kew three years later, in 1914. All three sons became bank clerks or cashiers, but Alfred joined the Canadian Army, fought in World War 1, dying in hospital in Boulogne of wounds sustained in battle in 1916.

So our social player, then, was, like most of the other players we’ve met at Twickenham and Richmond Chess Clubs in the 1880s and 1890s, a fairly prosperous chap. Perhaps he wasn’t a strong player, but he must have enjoyed his chess and, as a result, died happy. I guess that’s the most important thing.

Sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Other online sources referenced above