It’s a good day for any chess club when a player strong enough to play on top board turns up at your door. When he brings his three strong chess playing sons with him as well it must be something rather special.

That’s what happened at Twickenham Chess Club in 1891 when the Humphreys family moved into the area.

Edmund Elias Humphreys had been born in Chelsea in 1831. He married Louisa Telfer in 1854 and the young couple settled in Hackney, North East London. At some point in the mid 1860s they moved south to Clapham. Edmund was a senior clerk working for the Civil Service Commissioners, so the family were quite well off.

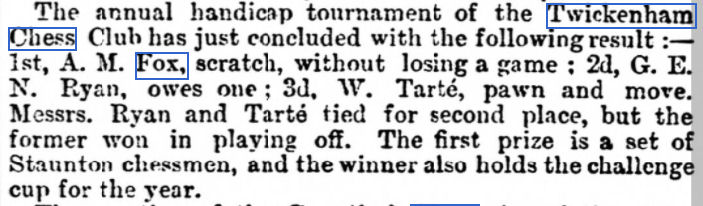

Edmund was a keen and pretty strong chess player back then. In 1862 he was a member of St James’ Club, where his opponents included Alexander Sich, and by the early 1870s he was playing at the City of London Club, giving odds to most of his opponents in handicap tournaments. Rod Edwards suggest he was round about 2000 strength: a decent county standard player. As you’d expect, he taught his sons (and perhaps also his daughters) to play his favourite game.

Unlike, for example, Arthur Makinson Fox, the family never stayed at the same address very long, and by the time of the 1891 census they’d moved to Teddington Park, just off Waldegrave Road, where their daughter Louisa junior was living with her husband and large family, and where, a few years later, Noël Coward would be born. (Confusingly, Teddington Park and Teddington Park Road are both turnings off Waldegrave Road.) Edmund and Louisa’s household was completed by their three youngest children, a niece and two servants.

Edmund’s oldest surviving son, Edmund Walter Humphreys, had been born in 1860. By 1891 he was working as an accountant, was married with two daughters and living in New Malden, not very far from the station, from where a short train journey would take him to Teddington and Twickenham. IM Gavin Wall now lives on the same estate.

Herbert Arthur Humphreys was born in 1864, and was still at home with his parents in 1891. Rather unexpectedly, he was working as a seedsman, and would later become a market gardener.

The youngest son was born Frederick Thomas Hudson Humphreys in 1869, but seems to have been known as F H Humphreys. He was also living at home in 1891, with his occupation listed as ‘None’. In those days when work for a young man from that background was easy to come by, this suggests he may have had some sort of health problem.

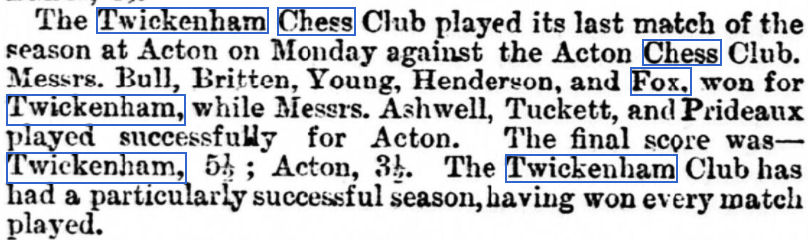

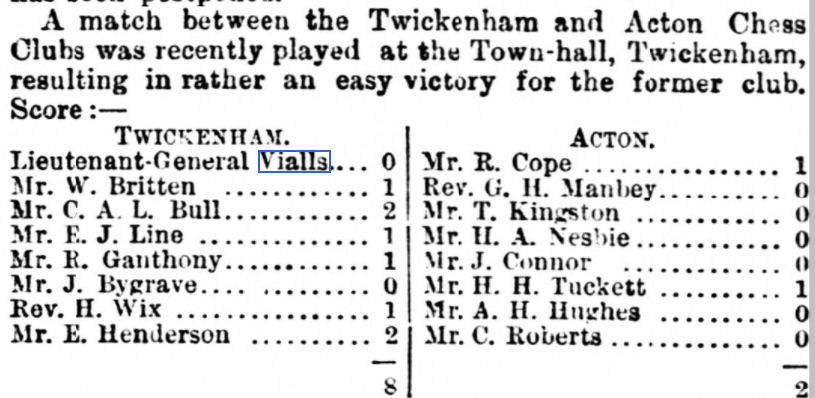

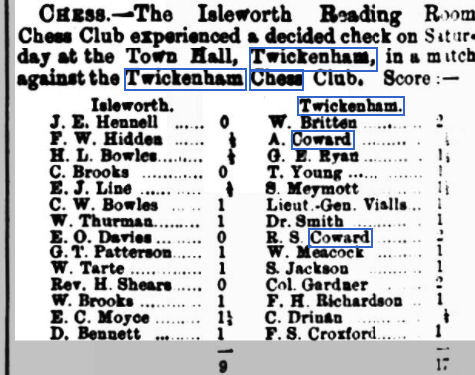

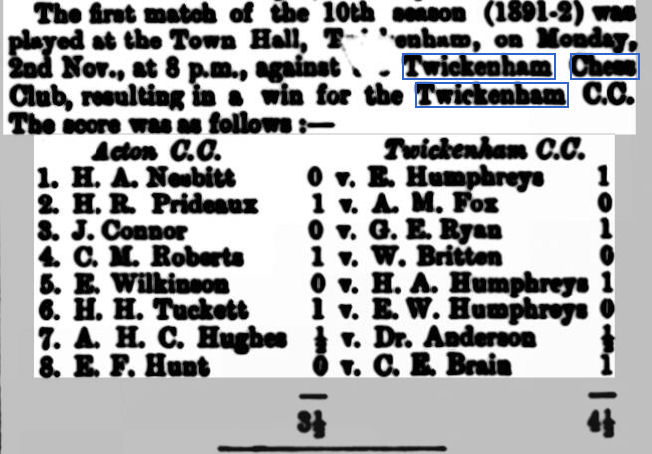

The first Twickenham chess record currently available for them is a match against Acton later in 1891. Perhaps they’d all joined the club for the start of the season.

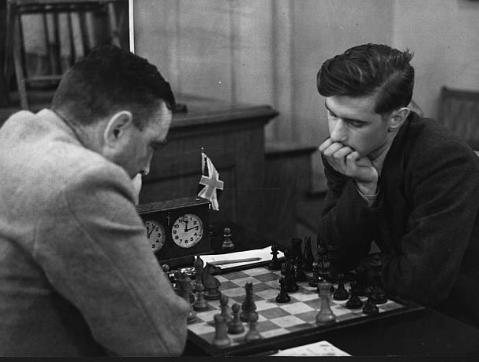

Here, we see Edmund Elias winning his game on top board, playing ahead of club stars Arthur Makinson Fox, George Edward Norwood Ryan and Wallace Britten, with Herbert and Edmund junior also in the team.

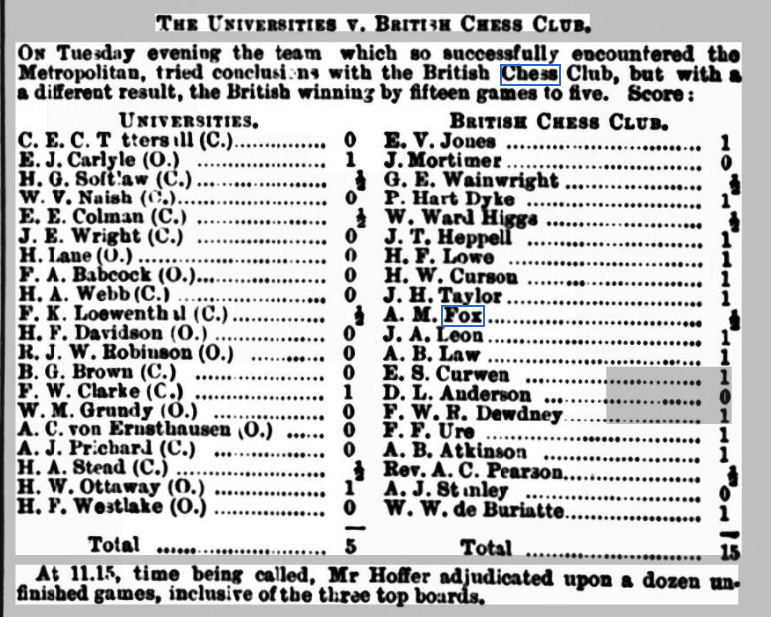

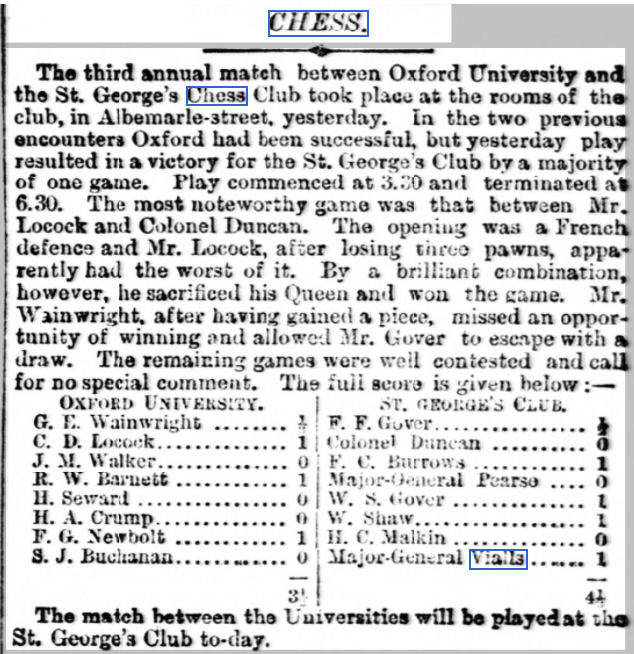

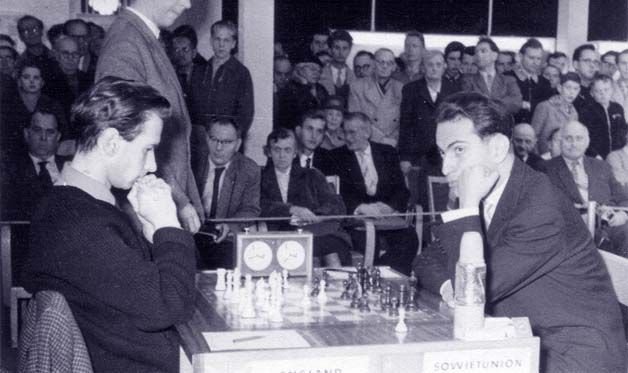

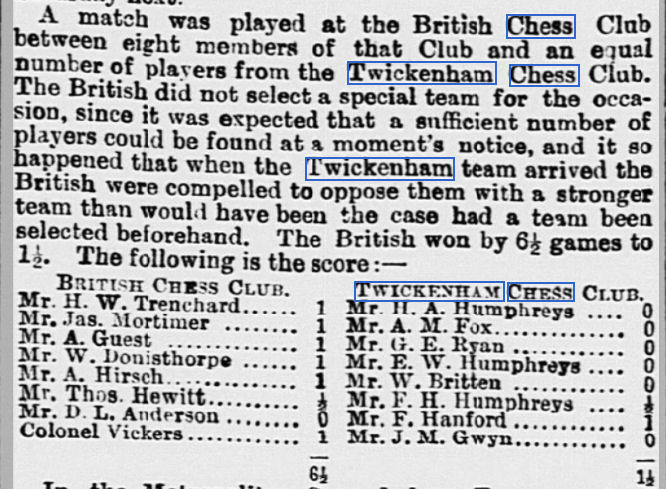

In 1893 Twickenham visited the British Chess Club, where they were facing stronger opposition than expected.

It sounds from the report that the British Chess Club were planning to recruit whoever was there at the time to play in the match, and, by chance, a lot of strong players turned up. Their top five boards were all of genuine master standard (and all worthy of future posts, as indeed is Mr Hewitt) so it’s not surprising this proved a bridge too far for the Twickenham chess players. It looks very much like the 1890s equivalent of a London League match against Wood Green.

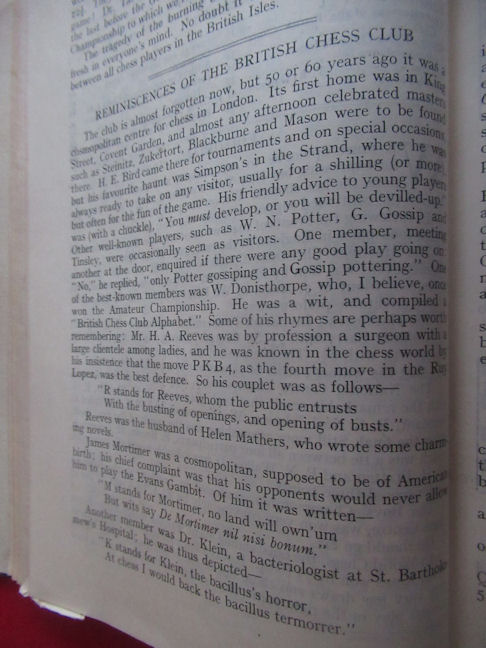

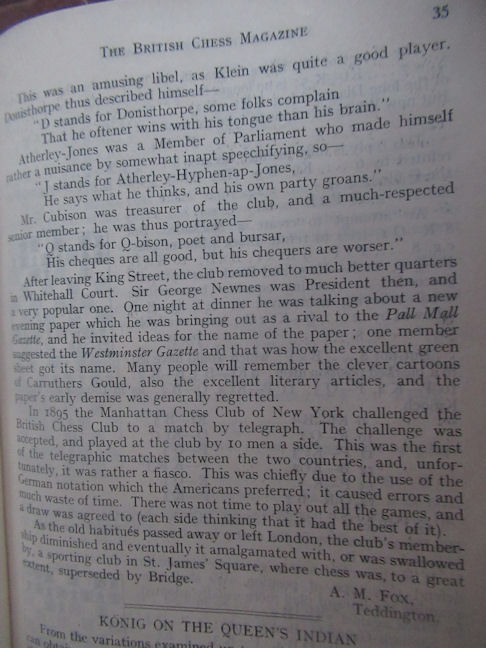

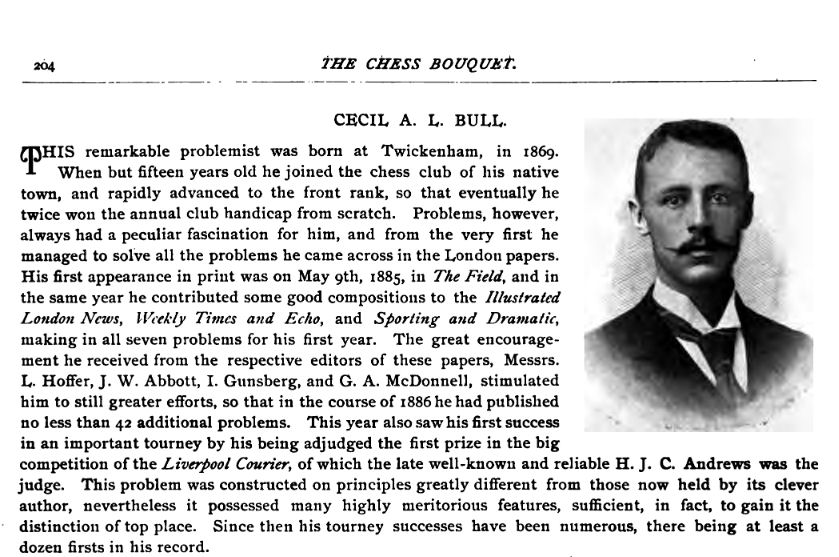

The life of the BCC top board is celebrated here.

Streatham and Brixton chess chronicler Martin Smith wrote about the BCC’s fourth board here.

You will note that Edmund senior wasn’t playing, but that Herbert had been promoted to top board, with Edmund junior and Frederick lower down.

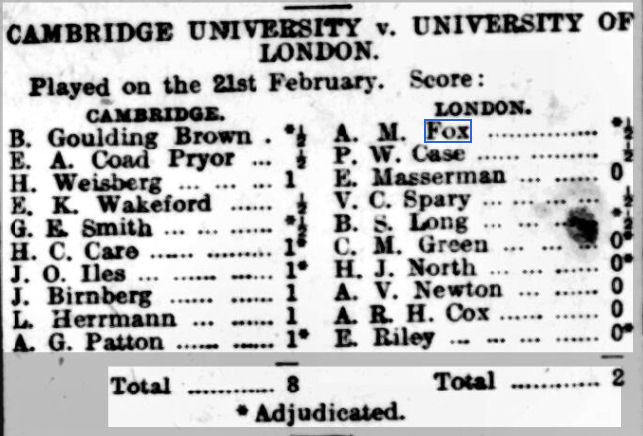

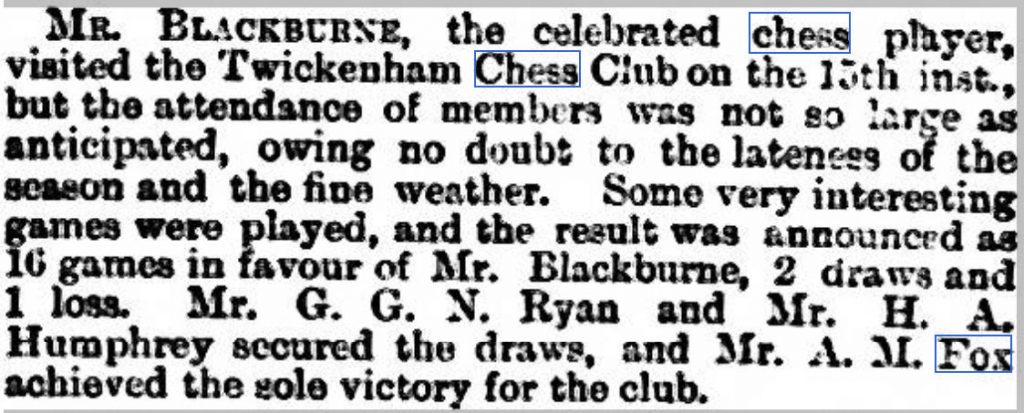

If you’ve been paying attention you’ll already have seen our next exhibit.

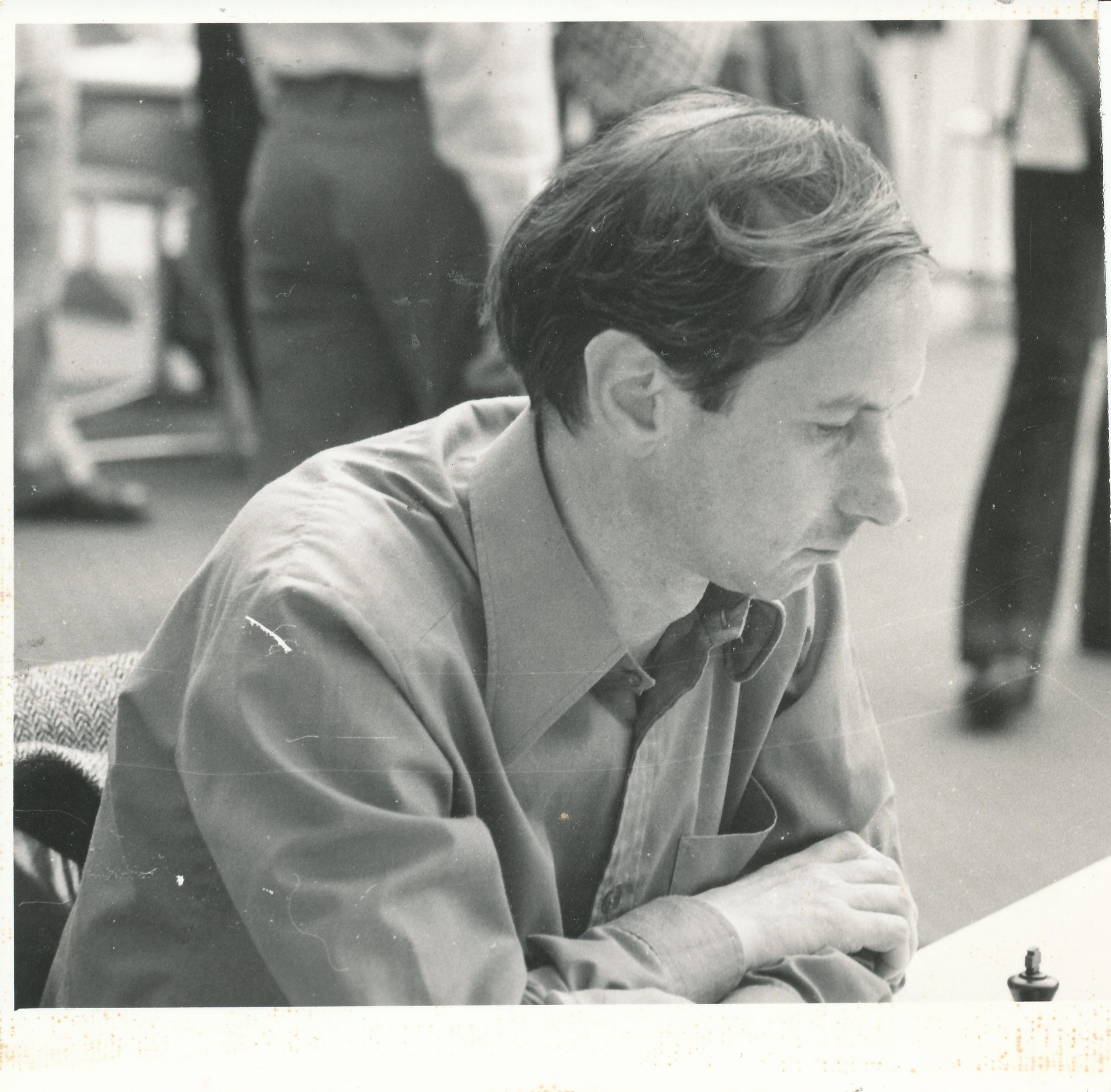

Here, we see Herbert, who seems to have been the strongest of the three brothers, taking a half point off Joseph Blackburne in a simul.

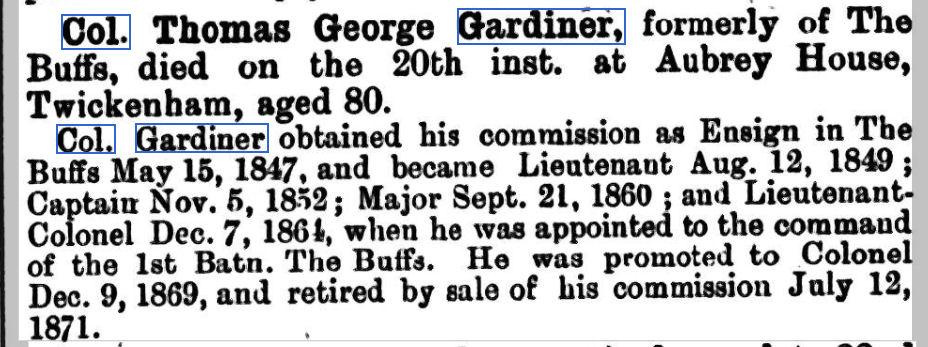

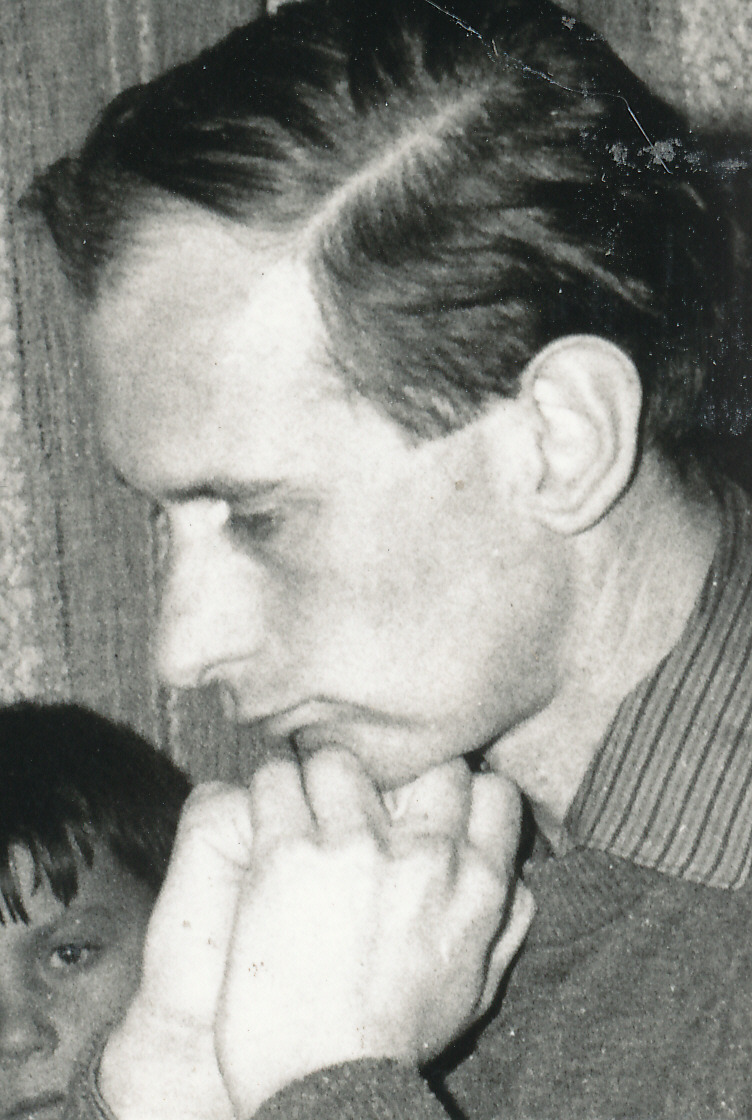

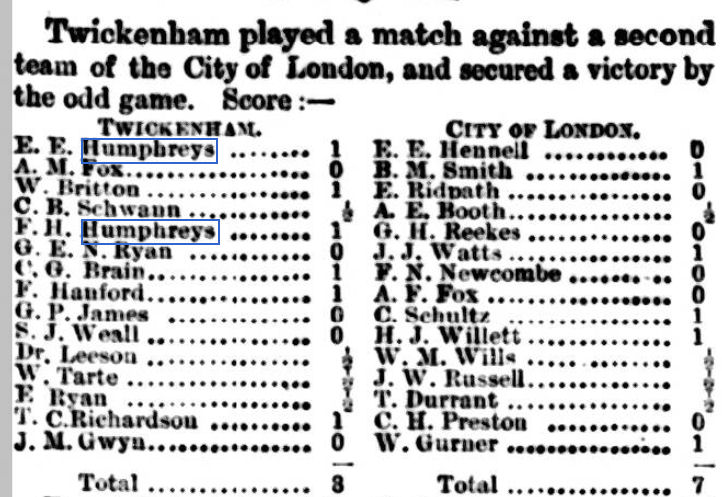

Moving on to 1894, here’s a match between Twickenham and the City of London Club’s second team.

A narrow win for the good guys, then, and a few interesting new names in the Twickenham team to whom we’ll return in future articles. (No, before you ask, GP James isn’t related to me.)

You’ll spot Edmund senior back on top board, with Frederick also playing, but Edmund junior and Herbert not in the team.

It seems the Humphreys family didn’t stay very long in Teddington as that’s the last we see of them locally.

By 1901 they’d moved across South London to Sydenham where Edmund Elias Humphreys, at the age of 69, was now the Manager of a Public Company (Corporation?) and Stock Exchange Jobber. Louisa and their unmarried daughter Florence were there, along with three granddaughters, perhaps just paying them a visit, and two servants.

Herbert had by now married, and was a market gardener out in Farnham, Surrey, and Frederick was nowhere to be found.

They were still in Sydenham in 1911: Edmund had now retired, and would die later that year. Florence was still there, along with a granddaughter and, again, two servants. There’s a possible death record for Louisa in 1915.

One more question: what happened to Frederick? We can make a rather sad speculation. There’s a death record for a Frederick H Humphreys of the right age recorded in Epsom in the first quarter of 1917. Epsom, as you may know, is the home of a number of psychiatric hospitals, or lunatic asylums as they were called in those days. Perhaps this was our man, also providing a possible explanation for his lack of employment in 1891. Nobody seems to know.

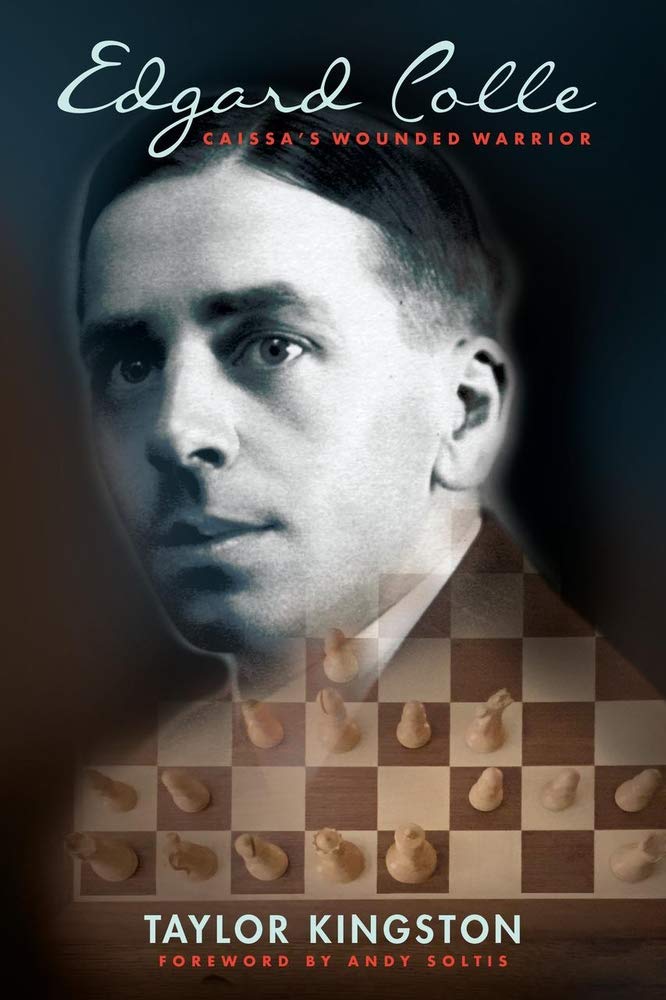

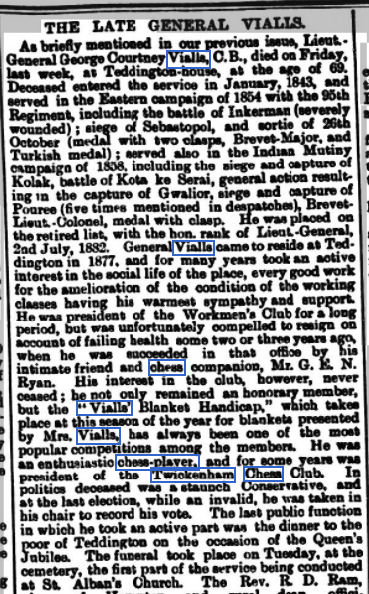

The story of the Humphreys family and their brief membership of Twickenham Chess Club takes us up to the mid 1890s, when chess in our Borough would undergo a significant transformation. But there’s one more, very significant, name to investigate first.

You’ll find out more in future Minor Pieces. Don’t you dare miss them.