Remembering Theophilus Harding Willcocks (19-iv-1912 14-iv-2014)

An innovator in both mathematics and fairy chess.

Here is an excellent article on squaring.net

An article from matplus.net

Remembering Theophilus Harding Willcocks (19-iv-1912 14-iv-2014)

An innovator in both mathematics and fairy chess.

Here is an excellent article on squaring.net

An article from matplus.net

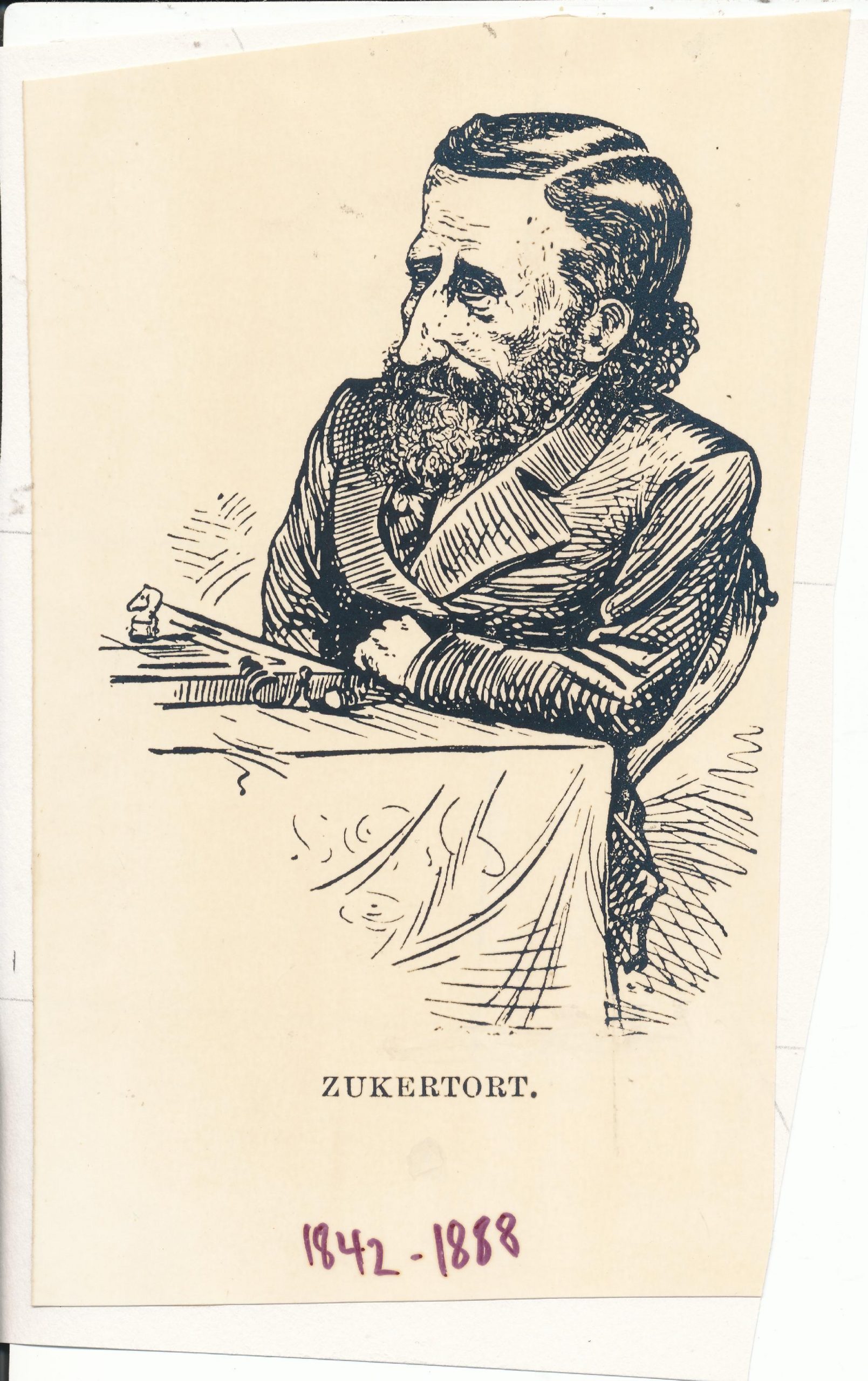

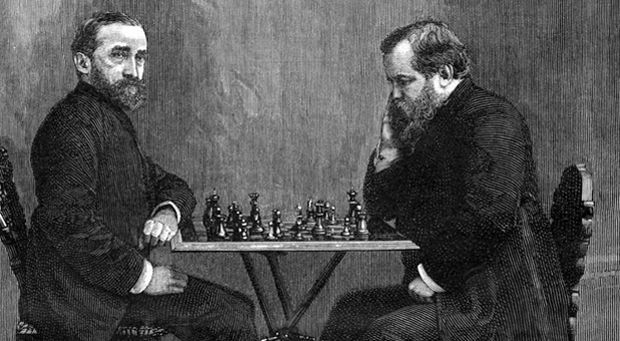

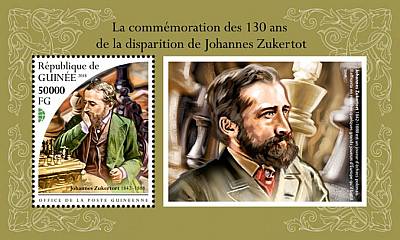

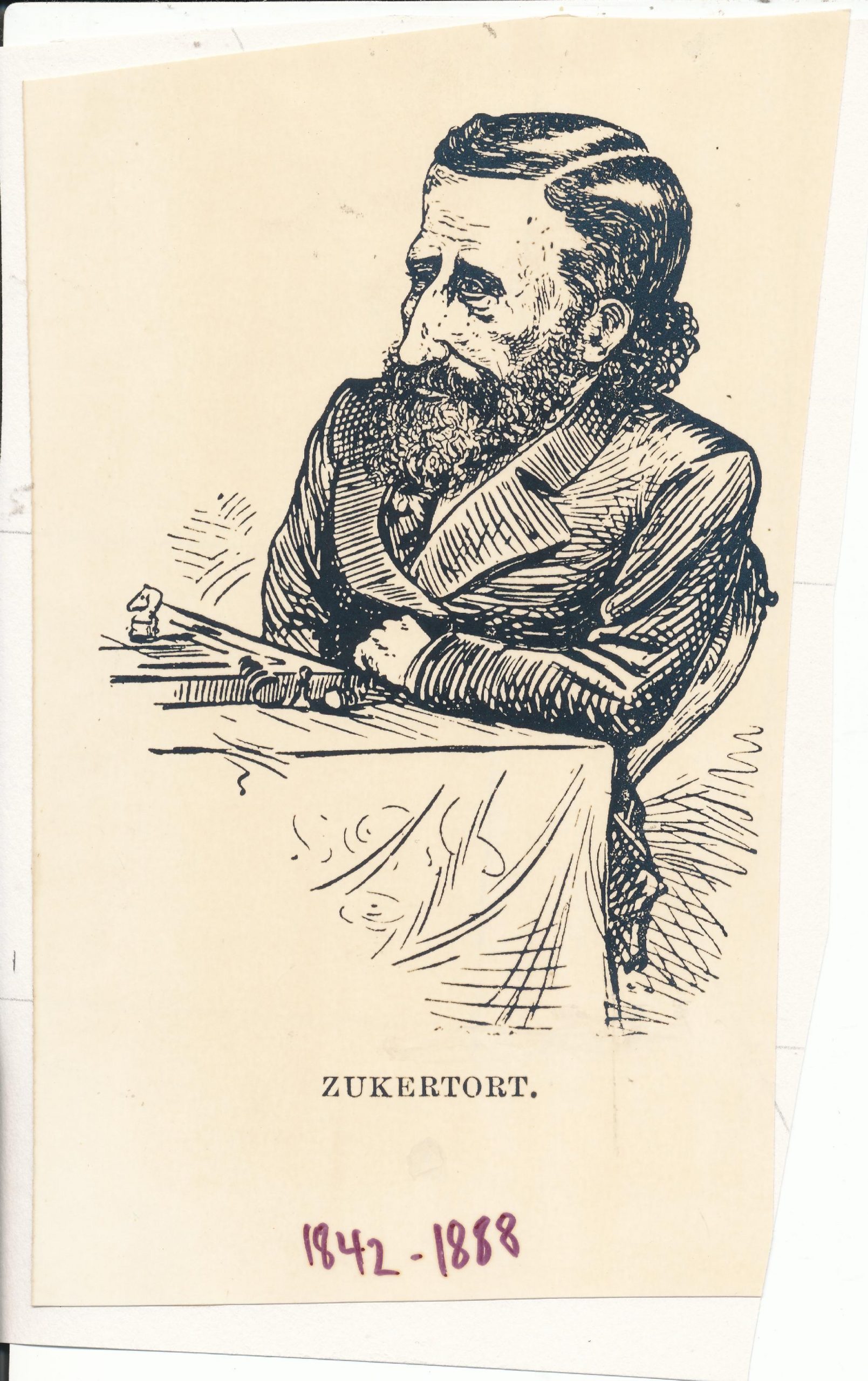

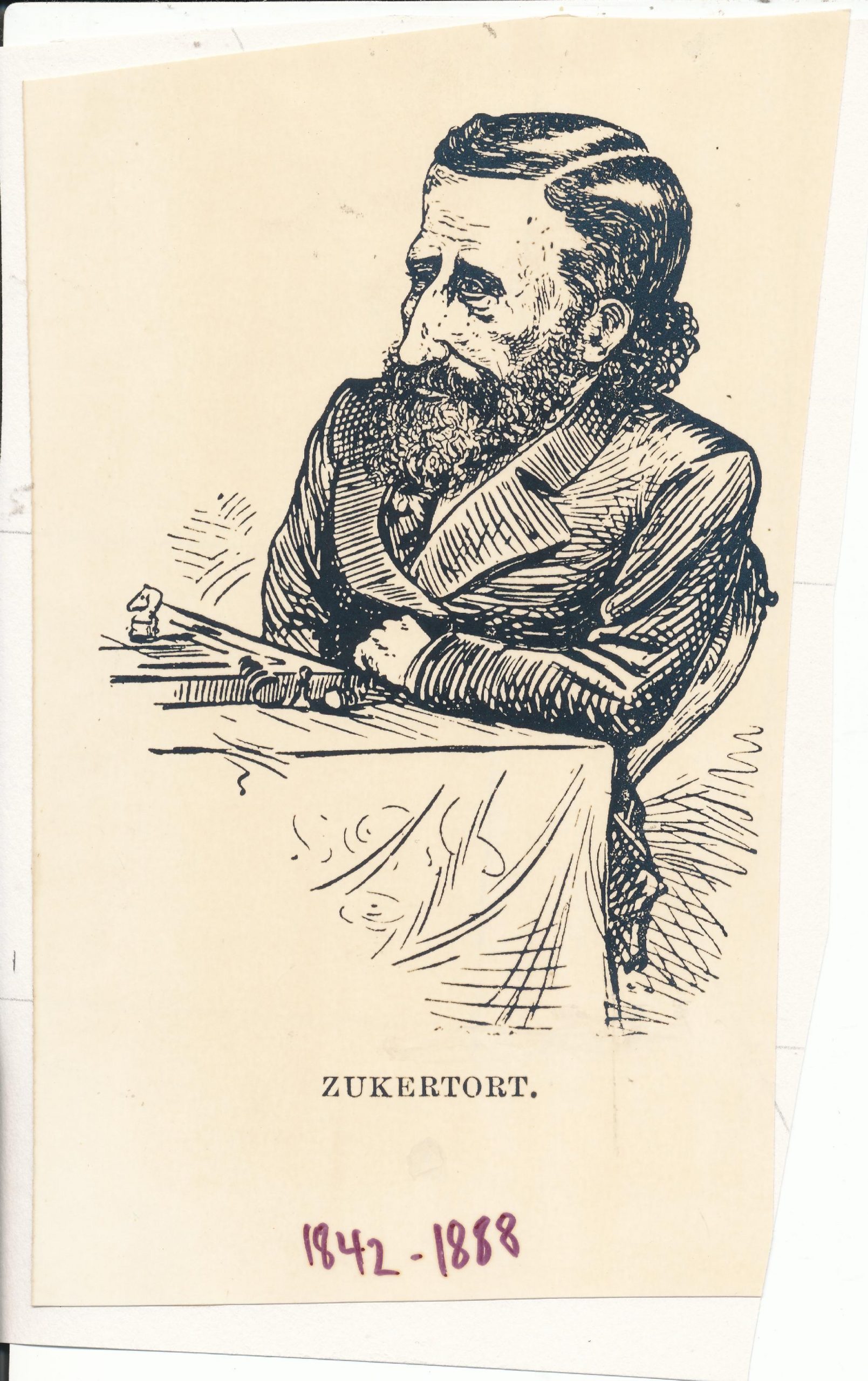

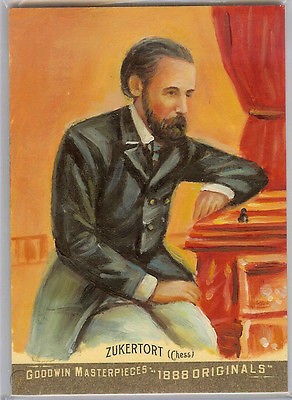

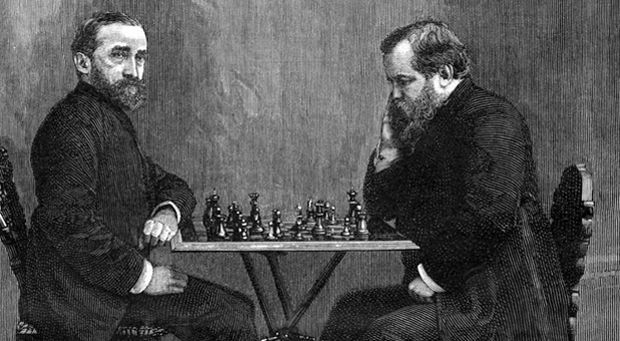

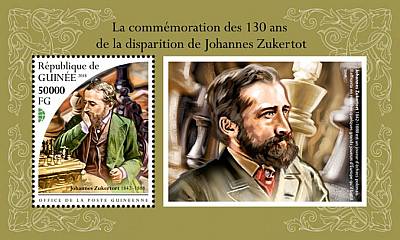

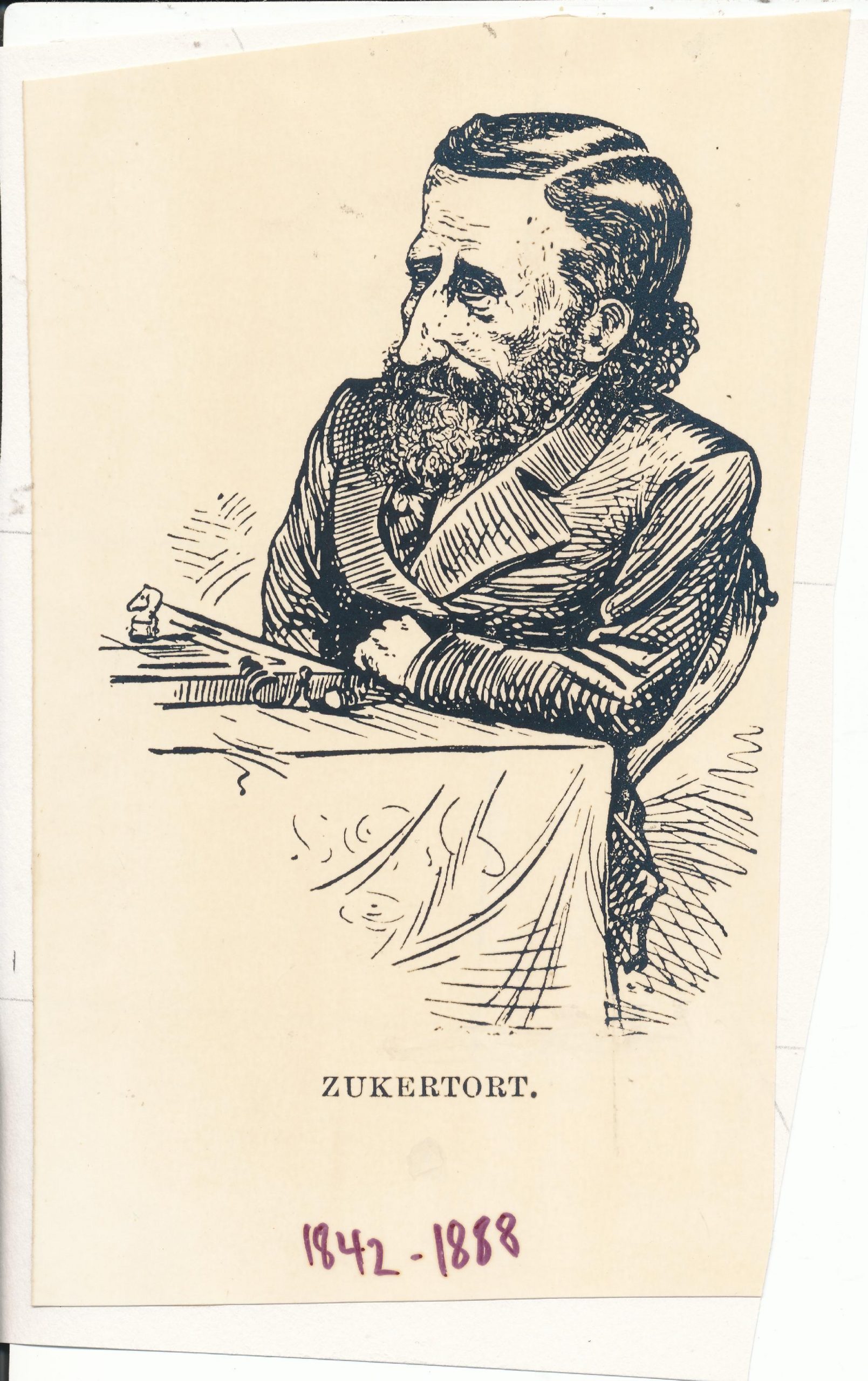

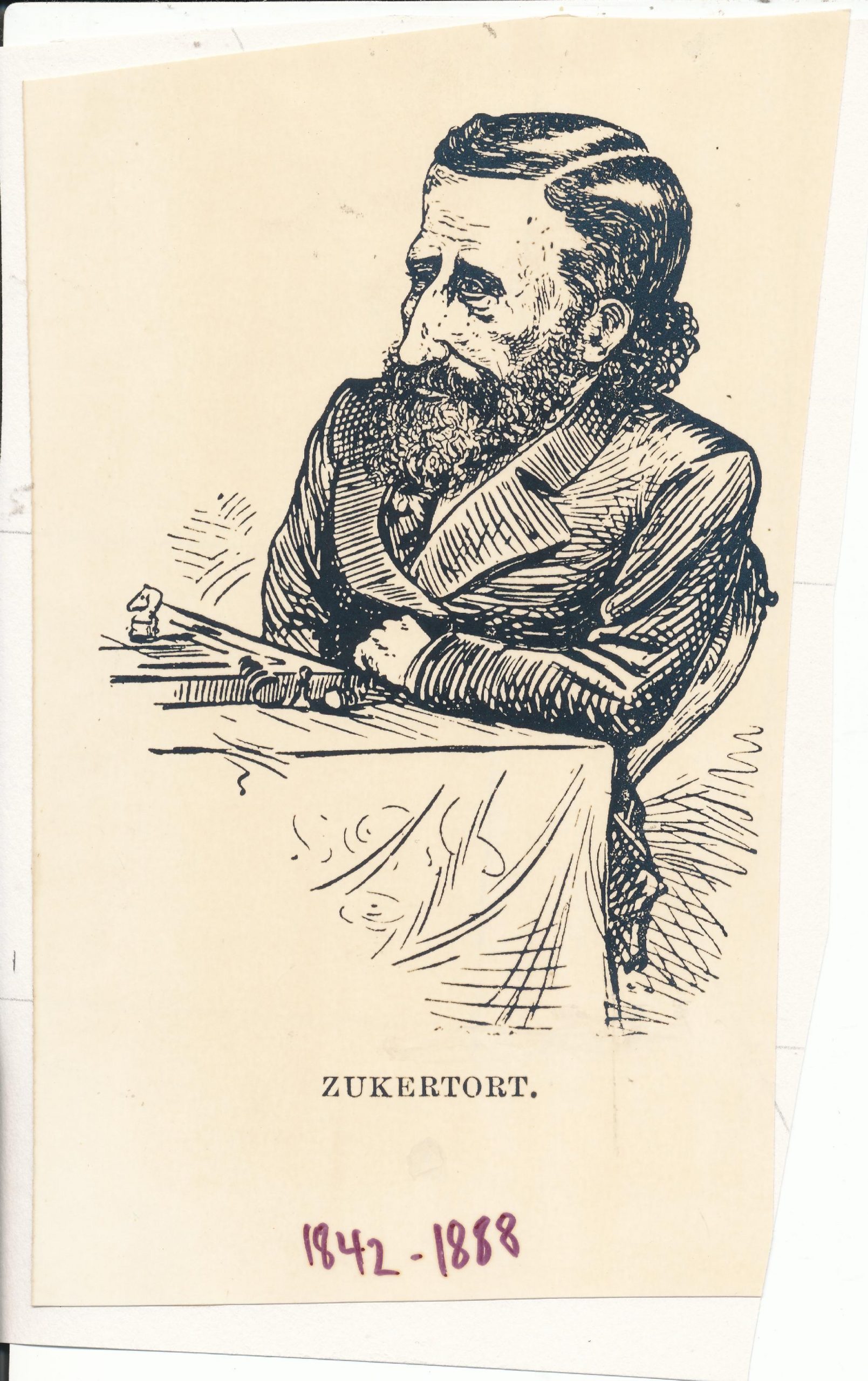

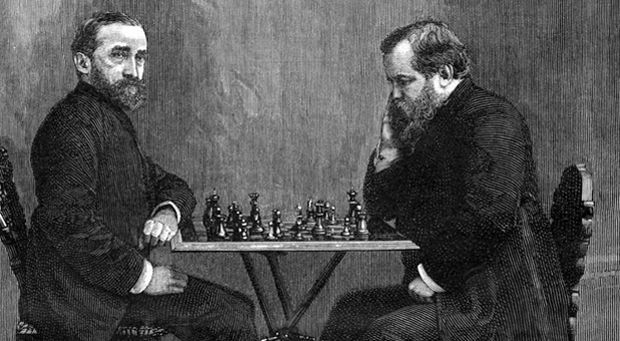

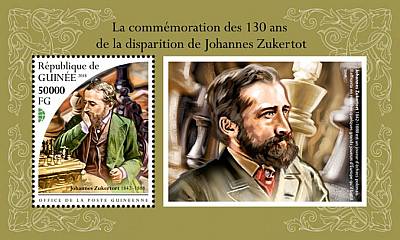

BCN Remembers Johannes Hermann Zukertort (07-ix-1842 20-vi-1888)

From the July 2012 editorial in British Chess Magazine we had this report :

“Johann Hermann Zukertort’s (1842-1888) grave was rededicated last month in London’s crowded Brompton Cemetery, largely thanks to an initiative led by Stuart Conquest. The resting place of one of the leading players of the nineteenth century was recorded but the grave had fallen into terrible dis-repair. See BCM 1888, pp.307-8 and p.338-340 for the obituary of the great man. We read that his death ‘was terribly sudden’, that he was buried on 26th June, 1888 and that ‘several pretty wreaths were laid on the coffin …’”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

Polish-born Jew, from about 1871 to 1886 second player in the world after Steinitz. From about 1862 to 1866 Zukertort, then living in Breslau, played many friendly games with Anderssen, at first receiving odds of a knight but soon meeting on even terms. They played two matches in Berlin, Zukertort losing the first in 1868 (+3 = 1—8) and winning the second in 1871 (+5 — 2).

In 1872 a group of London players, anxious to find someone who could defeat Steinitz, paid Zukertort 20 guineas to come to England. He came, he stayed, but he failed to beat Steinitz.

Zukertort took third place after Steinitz and Blackburne at London 1872, the strongest tournament in which He had yet played, and later in the year was decisively beaten by Steinitz in match play ( + 1=4—7). Zukertort settled in London as a professional player.

He won matches against Potter in 1872 ( + 4=8—2), Rosentalis in 1880 ( + 7=11-1), and Blackburne in 1881 ( + 7=5-2), He also had a fair record in tournament play: Leipzig 1877, second equal with Anderssen after L. Paulsen ahead of Winawer:-* Paris 1878, first ( + 14=5—3) equal with Winawer ahead of Blackburne (Zukertort won the play-off, +2=2); Berlin 1881, second alter Blackburne ahead of Winawer; and Vienna 1882, fourth equal with Mackenzie after Steinitz, Winawer, and Mason.

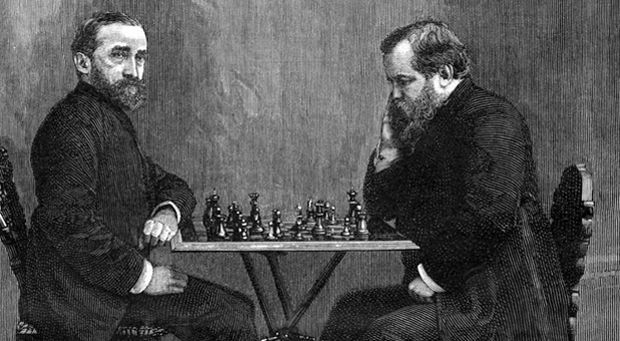

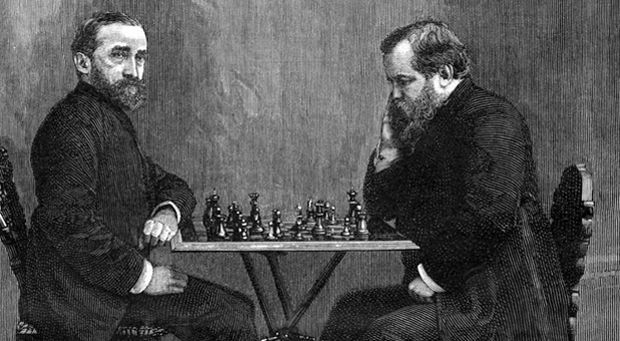

The world’s nine best players were among the competitors in the double-round London tournament of 1883 when Zukertort achieved his greatest victory: first prize (+22—4) three points ahead of Steinitz, the second prize winner, in seven weeks and a day he played 33 games (seven draws were replayed) and towards the end he relieved the strain by taking opiates, the cause of his losing his last three games. This victory led to the first match for the world championship, a struggle between him and Steinitz, USA, 1886. After nearly ten weeks of relentless pressure by his opponent Zukertort lost (- 1 – 5=5 —10) i winning only one of the last 15 games. His spirit crushed, his health failing, he was advised to give up competitive chess, but there was nothing else he could do. I am prepared, he said, l to be taken away at any moment.’ Seized by a stroke while playing at London’s famous coffee-house, Simpson’s Divan, he died the next day.

Like Anderssen, his teacher, Zukertort had a direct and straightforward style, and in combinative situations he could calculate far ahead. Having a prodigious memory he could recollect at will countless games and opening variations, a talent which may have limited his vision. (For his match with Steinitz in 1872 his extensive opening preparations brought him only one win. Steinitz was the better player in unfamiliar situations.) As an annotator and analyst Zukertort was outstanding in his time, and much of his work in these fields appeared in the Chess Monthly which he and Hoffer edited from 1879 to 1888.

Zukertort read widely and what he read became, as he said ‘iron-printed in my head’. Hoffer recalls Zukertort holding a visitor from India spellbound with a convincing and detailed account of a tiger-hunt, although it must have been outside his experience. Zukertort’s own account of his early life was reported in the Norfolk News, 16 Nov. 1872, He claimed aristocratic (Prussian and Polish) descent, and fluency in nine languages. “He learnt one language to read Dante, another to read Cervantes, and a third, Sanskrit, to trace the origin of chess,’ Besides the study of theology, philology, and social science he is also an original thinker on some of the problems that perplex humanity , ” He is ‘an accomplished swordsman, the best domino player in Berlin, one of the best whist players living, and so good a pistol shot that at fifteen paces he is morally certain to hit the ace of hearts . , , has found time to play 6,000 games of chess with Anderssen alone … a pupil of Moscheles, and in 1862-6 musical critic of the first journal in Silesia … is also a military veteran … he served in the Danish, in the Austrian, and in the French campaign , , , he was present at the following engagements, viz, in Denmark, Missunde, Duppcl, and Alsen; in Austria, Trauienau, Koniginhof, Kdniggratz (Sadowa), and Blumcnau; in France, Spicheeren, Pange (Vionville), Gravelotte, Noisevillc, and all other affairs before Metz, Twice dangerously wounded, and once left for dead upon the field, he is entitled to wear seven medals besides the orders of the Red Eagle and the Iron Cross, . . . He obtained the degree of M.D. at Breslau in 1865, having chiefly devoted his attention to chemistry under Professor Bunsen at Heidelberg, and to physiology at Berlin under Professor Virchow … is now on the staff of Prince Bismarck’s private organ, the Allgemeine Zetiling, and is chief editor of a political journal which receives “officios’” from the Government at Berlin. He is . . . the author of the Grosses Schach Handbuck and a Leitfaden , and , . . was for several years editor of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung. ’ There is some truth in the last sentence: he was co-author of the books, co-editor of the chess magazine.

A. Olson, J. H. Zukertort (1912) is a collection of 201 games with Swedish text.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks

“One of the leading players of the last century, Zukertort was born in Riga on 7th September 1842. His father was a Prussian and his mother a Pole. When he was 13, his family moved to Breslau. After studying chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, he obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University in 1865. He served as a doctor with the Prussian Army during his country’s wars against Denmark, Austria and France and was decorated for gallantry.

Zukertort was a man of many talents. He had a prodigious memory, and it was said that he never forgot a game he had played. He spoke 11 languages, and he was an excellent pistol shot and fencer but it was journalism and chess that he chose for a career.

Zukertort learned to play chess when he was 18, and two years later he met Anderssen and became his pupil. Within three years he had become one of the strongest players in North Germany. He first drew attention to himself as a blindfold simultaneous player. In 1868, he gave a simultaneous blindfold display against seven players in Berlin. This was his first blindfold performan@, and it was so successful that he gave several further performances, almost immediately increasing the number of his opponents to 12.

Between 1867 and 1871, he was joint editor with Anderssen of the Neue Berliner Schachzeityng. In 1871 he played a match against Anderssen, probably the second strongest player in the world at that time, and beat_him by 5-2. Following this victory, he was invited to take part in the 1872 London Tournament. He came 3rd and, probably because he was disappointed at his result, immediately challenged – the winner, Steinitz, to a match for the title of World Champion. Steinitz had claimed this title after his victory over Anderssen in 1866. Zukertort lost the match by + 1 -7 :4.

Meanwhile, Zukertort had decided to make England his permanent home and became a naturalised Englishman in l878.

Zukertort tied with Anderssen for 2nd prize in a master tournament in Leipzig in 1877, but his first major international event was Paris 1878, when he tied for lst place with Winawer and won the play-oft. In 1880 he beat the French champion, Rosenthal, in a match 7-1, and the following year he beat Blackburne +7 -2 – 5. The greatest performance of his career came in 1883, when in the London Tournament he won lst prize, three points ahead of Steinitz, who came 2nd. His victory was certain two weeks before the end of the tournament when he had a score of 22 out of 23. With victory secure, he went on to lose his last three games, the strain having proved too much.

Zukertort was advised by his doctor to give up serious chess but he refused and within a short time left England for a chess tour of the United States, Canada and Europe. On his return from this tour, he left almost immediately to play a second match for the world title against Steinitz. This took place in 1886. Zukertort was in no fit state of health

for such a match, and it proved too much for him. He lost by +5 -10 =5 and returned to England a physical and nervous wreck.

Zukertort never fully recovered. He continued to play chess, but with little success. He died at Charing Cross Hospital on 20th June 1888 of cerebral haemorrhage, following a game at Simpson’s ‘Divan’.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

“One of the most talented players of all time and possibly an English Prussian Polish Jewish grandmaster, the antecedents and early career of Zukertort are shrouded in mystery, a mystery that was the more complete in that the only account of these comes from Zukertort with a lack of corroboration so great that perhaps he really was telling the truth. Whatever the truth may be it is certain that he was a great chess player, one of those who carry with them the aura of certain genius. According to Zukertort, then, he was born in Lublin of mixed Prussian and Polish descent and his mother was the Baroness Krzyzanovska. The name of his mother sounds incredibly like an invention of W. C. Fields and it is difficult to believe that his father’s name, Zukertort, was not Jewish.

Again according to Zukertort he studied chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, claiming to have obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University. His versatility was astonishing. He spoke nine languages including Hebrew and was acquainted with several more. He had been a soldier, having fought in several campaigns for Prussia against Austria, Denmark and France; and once had been left for dead on the battlefield.

A music critic, editor of a political paper, on the staff of Bismarck’s newspaper, the Allgemeine Zeitung; gifted with a memory so colossal that he never forgot a game he played; a consummate fencer, a blindfold simultaneous player of undoubted repute (he had played as many as fifteen simultaneously blindfold) and a grandmaster with justified pretensions towards the world title: most of these attributes we have to take on Zukertort’s word. But there is enough left that is substantiated to show his great importance in the history of chess.

His early chess career had much to do with Anderssen whom he beat in a match, when Anderssen had grown old, in 1871 in Germany by +5-2, having lost a previous match to him in Berlin in 1868 by +3 -8 =1. On the strength of his win over Anderssen in the second match he was invited to play in a small but strong tournament in London in 1872 where he came 3rd below Steinitz and Blackburne. Immediately afterwards he played a match with Steinitz in which he was overwhelmingly defeated by +1-7 =4.It is unlikely that this was for the World Championship since no mention was made of the title at the time and the stakes were small, £2O for the winner and £l0 for the loser.

Despite this disastrous loss, which contained the seeds of further disasters, Zukertort felt that London was his true home and decided to stay in England, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1878. His results in tournament and match play from then on showed a steep upward curve. He was 2nd in London 1876, lst in a small tournament in Cologne 1877 and :2nd at Leipzis that year. He came lst in a big tournament at Paris 1878 where he tied with Winawer and won the play-off.

In 1880 he won a match in London against Rosenthal by +7 -l =11 and in the following year he was 2nd to Blackburne in Berlin. He was no less than 3 points behind Blackburne but he avenged this by beating him in a match in London the same year by +7 -2 =5.

A comparative setback came in a great tournament at Vienna in 1882 when he tied for fourth place with Mackenzie, below Steinitz, Winawer and Mason but in 1883 came the peak of his career when

he won lst prize in the great London tournament, 3 points ahead of Steinitz and 5.5 points ahead of Blackburne who came 3rd.

The remarkable nature of his victory is to be seen from the fact that he was sure of first prize with some two weeks still to go when he had a score of 22/23. But, ominously, his health was giving way and he had been sustaining himself by the use of drugs. He lost his last three games. It is very probable that this high point in his career was also the time when his health began to deteriorate under the excessive nervous strains by his conscious efforts to out rival Steinitz.

Thus, though he had been warned by his doctor he refused to abandon serious play and in 1886 he played his match for the World Championship against Steinitz in the USA, losing by +S -10 =5. The strain was this time too great an and he returned to England with his health completely shattered.

This was reflected in his subsequent results. =7th in London 1886 and =3rd in a smaller tournament at Nottingham that year, he had disastrous results throughout 1887: =l5th at Frankfurt-am-Main, 4th in a small tournament in London and a match loss there to Blackburne by +1-5:8.

In the last year of his life he was =7th in London in 1888 playing to the last possible moment, he died from a cerebral haemorrhage after a game at Simpson’s Divan.

Despite a career that stopped as if it were halfway, Zukertort is clearly one of the chess immortals and there is about his best game a sort of resilient and shining splendour that no other player possesses.”

Zukertort was buried in the Brompton Cemetry. He are details.

The grave was rededicated in 2012 thanks to the efforts of many chess enthusiasts.

Several opening variations have been named after Zukertort :

The Zukertort Defence in the Vienna Game, a variation advocated by Zukertort from 1871.

After 6 exd5 Bg4T 7 Nf3 Black castles, sacrificing a piece for counterattack :

The Zukertort Opening, 1.Nf3 abhorred by Ruy Lopez, used by Zukertort always as a preliminary

to 2.d4, now the fourth most popular opening move, after 1.e4, 1.d4, and 1 c4.

The Zukertort variation, in the Spanish opening, favoured by Zukertort in the 1880s :

but laid to rest soon after.

The Zukertort Variation in the Philidor Defence :

Possibly the Colle-Zukertort Opening is the most well-known

and still continues to be written about to this day.

He was inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2016.

Here is an interesting article from the ruchess web site.

Dominic Lawson wrote this article in 2014.

An interesting article from chess.com

Here is his Wikipedia entry

BCN Remembers Johannes Hermann Zukertort (07-ix-1842 20-vi-1888)

From the July 2012 editorial in British Chess Magazine we had this report :

“Johann Hermann Zukertort’s (1842-1888) grave was rededicated last month in London’s crowded Brompton Cemetery, largely thanks to an initiative led by Stuart Conquest. The resting place of one of the leading players of the nineteenth century was recorded but the grave had fallen into terrible dis-repair. See BCM 1888, pp.307-8 and p.338-340 for the obituary of the great man. We read that his death ‘was terribly sudden’, that he was buried on 26th June, 1888 and that ‘several pretty wreaths were laid on the coffin …’”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

Polish-born Jew, from about 1871 to 1886 second player in the world after Steinitz. From about 1862 to 1866 Zukertort, then living in Breslau, played many friendly games with Anderssen, at first receiving odds of a knight but soon meeting on even terms. They played two matches in Berlin, Zukertort losing the first in 1868 (+3 = 1—8) and winning the second in 1871 (+5 — 2).

In 1872 a group of London players, anxious to find someone who could defeat Steinitz, paid Zukertort 20 guineas to come to England. He came, he stayed, but he failed to beat Steinitz.

Zukertort took third place after Steinitz and Blackburne at London 1872, the strongest tournament in which He had yet played, and later in the year was decisively beaten by Steinitz in match play ( + 1=4—7). Zukertort settled in London as a professional player.

He won matches against Potter in 1872 ( + 4=8—2), Rosentalis in 1880 ( + 7=11-1), and Blackburne in 1881 ( + 7=5-2), He also had a fair record in tournament play: Leipzig 1877, second equal with Anderssen after L. Paulsen ahead of Winawer:-* Paris 1878, first ( + 14=5—3) equal with Winawer ahead of Blackburne (Zukertort won the play-off, +2=2); Berlin 1881, second alter Blackburne ahead of Winawer; and Vienna 1882, fourth equal with Mackenzie after Steinitz, Winawer, and Mason.

The world’s nine best players were among the competitors in the double-round London tournament of 1883 when Zukertort achieved his greatest victory: first prize (+22—4) three points ahead of Steinitz, the second prize winner, in seven weeks and a day he played 33 games (seven draws were replayed) and towards the end he relieved the strain by taking opiates, the cause of his losing his last three games. This victory led to the first match for the world championship, a struggle between him and Steinitz, USA, 1886. After nearly ten weeks of relentless pressure by his opponent Zukertort lost (- 1 – 5=5 —10) i winning only one of the last 15 games. His spirit crushed, his health failing, he was advised to give up competitive chess, but there was nothing else he could do. I am prepared, he said, l to be taken away at any moment.’ Seized by a stroke while playing at London’s famous coffee-house, Simpson’s Divan, he died the next day.

Like Anderssen, his teacher, Zukertort had a direct and straightforward style, and in combinative situations he could calculate far ahead. Having a prodigious memory he could recollect at will countless games and opening variations, a talent which may have limited his vision. (For his match with Steinitz in 1872 his extensive opening preparations brought him only one win. Steinitz was the better player in unfamiliar situations.) As an annotator and analyst Zukertort was outstanding in his time, and much of his work in these fields appeared in the Chess Monthly which he and Hoffer edited from 1879 to 1888.

Zukertort read widely and what he read became, as he said ‘iron-printed in my head’. Hoffer recalls Zukertort holding a visitor from India spellbound with a convincing and detailed account of a tiger-hunt, although it must have been outside his experience. Zukertort’s own account of his early life was reported in the Norfolk News, 16 Nov. 1872, He claimed aristocratic (Prussian and Polish) descent, and fluency in nine languages. “He learnt one language to read Dante, another to read Cervantes, and a third, Sanskrit, to trace the origin of chess,’ Besides the study of theology, philology, and social science he is also an original thinker on some of the problems that perplex humanity , ” He is ‘an accomplished swordsman, the best domino player in Berlin, one of the best whist players living, and so good a pistol shot that at fifteen paces he is morally certain to hit the ace of hearts . , , has found time to play 6,000 games of chess with Anderssen alone … a pupil of Moscheles, and in 1862-6 musical critic of the first journal in Silesia … is also a military veteran … he served in the Danish, in the Austrian, and in the French campaign , , , he was present at the following engagements, viz, in Denmark, Missunde, Duppcl, and Alsen; in Austria, Trauienau, Koniginhof, Kdniggratz (Sadowa), and Blumcnau; in France, Spicheeren, Pange (Vionville), Gravelotte, Noisevillc, and all other affairs before Metz, Twice dangerously wounded, and once left for dead upon the field, he is entitled to wear seven medals besides the orders of the Red Eagle and the Iron Cross, . . . He obtained the degree of M.D. at Breslau in 1865, having chiefly devoted his attention to chemistry under Professor Bunsen at Heidelberg, and to physiology at Berlin under Professor Virchow … is now on the staff of Prince Bismarck’s private organ, the Allgemeine Zetiling, and is chief editor of a political journal which receives “officios’” from the Government at Berlin. He is . . . the author of the Grosses Schach Handbuck and a Leitfaden , and , . . was for several years editor of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung. ’ There is some truth in the last sentence: he was co-author of the books, co-editor of the chess magazine.

A. Olson, J. H. Zukertort (1912) is a collection of 201 games with Swedish text.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks

“One of the leading players of the last century, Zukertort was born in Riga on 7th September 1842. His father was a Prussian and his mother a Pole. When he was 13, his family moved to Breslau. After studying chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, he obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University in 1865. He served as a doctor with the Prussian Army during his country’s wars against Denmark, Austria and France and was decorated for gallantry.

Zukertort was a man of many talents. He had a prodigious memory, and it was said that he never forgot a game he had played. He spoke 11 languages, and he was an excellent pistol shot and fencer but it was journalism and chess that he chose for a career.

Zukertort learned to play chess when he was 18, and two years later he met Anderssen and became his pupil. Within three years he had become one of the strongest players in North Germany. He first drew attention to himself as a blindfold simultaneous player. In 1868, he gave a simultaneous blindfold display against seven players in Berlin. This was his first blindfold performan@, and it was so successful that he gave several further performances, almost immediately increasing the number of his opponents to 12.

Between 1867 and 1871, he was joint editor with Anderssen of the Neue Berliner Schachzeityng. In 1871 he played a match against Anderssen, probably the second strongest player in the world at that time, and beat_him by 5-2. Following this victory, he was invited to take part in the 1872 London Tournament. He came 3rd and, probably because he was disappointed at his result, immediately challenged – the winner, Steinitz, to a match for the title of World Champion. Steinitz had claimed this title after his victory over Anderssen in 1866. Zukertort lost the match by + 1 -7 :4.

Meanwhile, Zukertort had decided to make England his permanent home and became a naturalised Englishman in l878.

Zukertort tied with Anderssen for 2nd prize in a master tournament in Leipzig in 1877, but his first major international event was Paris 1878, when he tied for lst place with Winawer and won the play-oft. In 1880 he beat the French champion, Rosenthal, in a match 7-1, and the following year he beat Blackburne +7 -2 – 5. The greatest performance of his career came in 1883, when in the London Tournament he won lst prize, three points ahead of Steinitz, who came 2nd. His victory was certain two weeks before the end of the tournament when he had a score of 22 out of 23. With victory secure, he went on to lose his last three games, the strain having proved too much.

Zukertort was advised by his doctor to give up serious chess but he refused and within a short time left England for a chess tour of the United States, Canada and Europe. On his return from this tour, he left almost immediately to play a second match for the world title against Steinitz. This took place in 1886. Zukertort was in no fit state of health

for such a match, and it proved too much for him. He lost by +5 -10 =5 and returned to England a physical and nervous wreck.

Zukertort never fully recovered. He continued to play chess, but with little success. He died at Charing Cross Hospital on 20th June 1888 of cerebral haemorrhage, following a game at Simpson’s ‘Divan’.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

“One of the most talented players of all time and possibly an English Prussian Polish Jewish grandmaster, the antecedents and early career of Zukertort are shrouded in mystery, a mystery that was the more complete in that the only account of these comes from Zukertort with a lack of corroboration so great that perhaps he really was telling the truth. Whatever the truth may be it is certain that he was a great chess player, one of those who carry with them the aura of certain genius. According to Zukertort, then, he was born in Lublin of mixed Prussian and Polish descent and his mother was the Baroness Krzyzanovska. The name of his mother sounds incredibly like an invention of W. C. Fields and it is difficult to believe that his father’s name, Zukertort, was not Jewish.

Again according to Zukertort he studied chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, claiming to have obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University. His versatility was astonishing. He spoke nine languages including Hebrew and was acquainted with several more. He had been a soldier, having fought in several campaigns for Prussia against Austria, Denmark and France; and once had been left for dead on the battlefield.

A music critic, editor of a political paper, on the staff of Bismarck’s newspaper, the Allgemeine Zeitung; gifted with a memory so colossal that he never forgot a game he played; a consummate fencer, a blindfold simultaneous player of undoubted repute (he had played as many as fifteen simultaneously blindfold) and a grandmaster with justified pretensions towards the world title: most of these attributes we have to take on Zukertort’s word. But there is enough left that is substantiated to show his great importance in the history of chess.

His early chess career had much to do with Anderssen whom he beat in a match, when Anderssen had grown old, in 1871 in Germany by +5-2, having lost a previous match to him in Berlin in 1868 by +3 -8 =1. On the strength of his win over Anderssen in the second match he was invited to play in a small but strong tournament in London in 1872 where he came 3rd below Steinitz and Blackburne. Immediately afterwards he played a match with Steinitz in which he was overwhelmingly defeated by +1-7 =4.It is unlikely that this was for the World Championship since no mention was made of the title at the time and the stakes were small, £2O for the winner and £l0 for the loser.

Despite this disastrous loss, which contained the seeds of further disasters, Zukertort felt that London was his true home and decided to stay in England, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1878. His results in tournament and match play from then on showed a steep upward curve. He was 2nd in London 1876, lst in a small tournament in Cologne 1877 and :2nd at Leipzis that year. He came lst in a big tournament at Paris 1878 where he tied with Winawer and won the play-off.

In 1880 he won a match in London against Rosenthal by +7 -l =11 and in the following year he was 2nd to Blackburne in Berlin. He was no less than 3 points behind Blackburne but he avenged this by beating him in a match in London the same year by +7 -2 =5.

A comparative setback came in a great tournament at Vienna in 1882 when he tied for fourth place with Mackenzie, below Steinitz, Winawer and Mason but in 1883 came the peak of his career when

he won lst prize in the great London tournament, 3 points ahead of Steinitz and 5.5 points ahead of Blackburne who came 3rd.

The remarkable nature of his victory is to be seen from the fact that he was sure of first prize with some two weeks still to go when he had a score of 22/23. But, ominously, his health was giving way and he had been sustaining himself by the use of drugs. He lost his last three games. It is very probable that this high point in his career was also the time when his health began to deteriorate under the excessive nervous strains by his conscious efforts to out rival Steinitz.

Thus, though he had been warned by his doctor he refused to abandon serious play and in 1886 he played his match for the World Championship against Steinitz in the USA, losing by +S -10 =5. The strain was this time too great an and he returned to England with his health completely shattered.

This was reflected in his subsequent results. =7th in London 1886 and =3rd in a smaller tournament at Nottingham that year, he had disastrous results throughout 1887: =l5th at Frankfurt-am-Main, 4th in a small tournament in London and a match loss there to Blackburne by +1-5:8.

In the last year of his life he was =7th in London in 1888 playing to the last possible moment, he died from a cerebral haemorrhage after a game at Simpson’s Divan.

Despite a career that stopped as if it were halfway, Zukertort is clearly one of the chess immortals and there is about his best game a sort of resilient and shining splendour that no other player possesses.”

Zukertort was buried in the Brompton Cemetry. He are details.

The grave was rededicated in 2012 thanks to the efforts of many chess enthusiasts.

Several opening variations have been named after Zukertort :

The Zukertort Defence in the Vienna Game, a variation advocated by Zukertort from 1871.

After 6 exd5 Bg4T 7 Nf3 Black castles, sacrificing a piece for counterattack :

The Zukertort Opening, 1.Nf3 abhorred by Ruy Lopez, used by Zukertort always as a preliminary

to 2.d4, now the fourth most popular opening move, after 1.e4, 1.d4, and 1 c4.

The Zukertort variation, in the Spanish opening, favoured by Zukertort in the 1880s :

but laid to rest soon after.

The Zukertort Variation in the Philidor Defence :

Possibly the Colle-Zukertort Opening is the most well-known

and still continues to be written about to this day.

He was inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2016.

Here is an interesting article from the ruchess web site.

Dominic Lawson wrote this article in 2014.

An interesting article from chess.com

Here is his Wikipedia entry

BCN Remembers Johannes Hermann Zukertort (07-ix-1842 20-vi-1888)

From the July 2012 editorial in British Chess Magazine we had this report :

“Johann Hermann Zukertort’s (1842-1888) grave was rededicated last month in London’s crowded Brompton Cemetery, largely thanks to an initiative led by Stuart Conquest. The resting place of one of the leading players of the nineteenth century was recorded but the grave had fallen into terrible dis-repair. See BCM 1888, pp.307-8 and p.338-340 for the obituary of the great man. We read that his death ‘was terribly sudden’, that he was buried on 26th June, 1888 and that ‘several pretty wreaths were laid on the coffin …’”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

Polish-born Jew, from about 1871 to 1886 second player in the world after Steinitz. From about 1862 to 1866 Zukertort, then living in Breslau, played many friendly games with Anderssen, at first receiving odds of a knight but soon meeting on even terms. They played two matches in Berlin, Zukertort losing the first in 1868 (+3 = 1—8) and winning the second in 1871 (+5 — 2).

In 1872 a group of London players, anxious to find someone who could defeat Steinitz, paid Zukertort 20 guineas to come to England. He came, he stayed, but he failed to beat Steinitz.

Zukertort took third place after Steinitz and Blackburne at London 1872, the strongest tournament in which He had yet played, and later in the year was decisively beaten by Steinitz in match play ( + 1=4—7). Zukertort settled in London as a professional player.

He won matches against Potter in 1872 ( + 4=8—2), Rosentalis in 1880 ( + 7=11-1), and Blackburne in 1881 ( + 7=5-2), He also had a fair record in tournament play: Leipzig 1877, second equal with Anderssen after L. Paulsen ahead of Winawer:-* Paris 1878, first ( + 14=5—3) equal with Winawer ahead of Blackburne (Zukertort won the play-off, +2=2); Berlin 1881, second alter Blackburne ahead of Winawer; and Vienna 1882, fourth equal with Mackenzie after Steinitz, Winawer, and Mason.

The world’s nine best players were among the competitors in the double-round London tournament of 1883 when Zukertort achieved his greatest victory: first prize (+22—4) three points ahead of Steinitz, the second prize winner, in seven weeks and a day he played 33 games (seven draws were replayed) and towards the end he relieved the strain by taking opiates, the cause of his losing his last three games. This victory led to the first match for the world championship, a struggle between him and Steinitz, USA, 1886. After nearly ten weeks of relentless pressure by his opponent Zukertort lost (- 1 – 5=5 —10) i winning only one of the last 15 games. His spirit crushed, his health failing, he was advised to give up competitive chess, but there was nothing else he could do. I am prepared, he said, l to be taken away at any moment.’ Seized by a stroke while playing at London’s famous coffee-house, Simpson’s Divan, he died the next day.

Like Anderssen, his teacher, Zukertort had a direct and straightforward style, and in combinative situations he could calculate far ahead. Having a prodigious memory he could recollect at will countless games and opening variations, a talent which may have limited his vision. (For his match with Steinitz in 1872 his extensive opening preparations brought him only one win. Steinitz was the better player in unfamiliar situations.) As an annotator and analyst Zukertort was outstanding in his time, and much of his work in these fields appeared in the Chess Monthly which he and Hoffer edited from 1879 to 1888.

Zukertort read widely and what he read became, as he said ‘iron-printed in my head’. Hoffer recalls Zukertort holding a visitor from India spellbound with a convincing and detailed account of a tiger-hunt, although it must have been outside his experience. Zukertort’s own account of his early life was reported in the Norfolk News, 16 Nov. 1872, He claimed aristocratic (Prussian and Polish) descent, and fluency in nine languages. “He learnt one language to read Dante, another to read Cervantes, and a third, Sanskrit, to trace the origin of chess,’ Besides the study of theology, philology, and social science he is also an original thinker on some of the problems that perplex humanity , ” He is ‘an accomplished swordsman, the best domino player in Berlin, one of the best whist players living, and so good a pistol shot that at fifteen paces he is morally certain to hit the ace of hearts . , , has found time to play 6,000 games of chess with Anderssen alone … a pupil of Moscheles, and in 1862-6 musical critic of the first journal in Silesia … is also a military veteran … he served in the Danish, in the Austrian, and in the French campaign , , , he was present at the following engagements, viz, in Denmark, Missunde, Duppcl, and Alsen; in Austria, Trauienau, Koniginhof, Kdniggratz (Sadowa), and Blumcnau; in France, Spicheeren, Pange (Vionville), Gravelotte, Noisevillc, and all other affairs before Metz, Twice dangerously wounded, and once left for dead upon the field, he is entitled to wear seven medals besides the orders of the Red Eagle and the Iron Cross, . . . He obtained the degree of M.D. at Breslau in 1865, having chiefly devoted his attention to chemistry under Professor Bunsen at Heidelberg, and to physiology at Berlin under Professor Virchow … is now on the staff of Prince Bismarck’s private organ, the Allgemeine Zetiling, and is chief editor of a political journal which receives “officios’” from the Government at Berlin. He is . . . the author of the Grosses Schach Handbuck and a Leitfaden , and , . . was for several years editor of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung. ’ There is some truth in the last sentence: he was co-author of the books, co-editor of the chess magazine.

A. Olson, J. H. Zukertort (1912) is a collection of 201 games with Swedish text.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks

“One of the leading players of the last century, Zukertort was born in Riga on 7th September 1842. His father was a Prussian and his mother a Pole. When he was 13, his family moved to Breslau. After studying chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, he obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University in 1865. He served as a doctor with the Prussian Army during his country’s wars against Denmark, Austria and France and was decorated for gallantry.

Zukertort was a man of many talents. He had a prodigious memory, and it was said that he never forgot a game he had played. He spoke 11 languages, and he was an excellent pistol shot and fencer but it was journalism and chess that he chose for a career.

Zukertort learned to play chess when he was 18, and two years later he met Anderssen and became his pupil. Within three years he had become one of the strongest players in North Germany. He first drew attention to himself as a blindfold simultaneous player. In 1868, he gave a simultaneous blindfold display against seven players in Berlin. This was his first blindfold performan@, and it was so successful that he gave several further performances, almost immediately increasing the number of his opponents to 12.

Between 1867 and 1871, he was joint editor with Anderssen of the Neue Berliner Schachzeityng. In 1871 he played a match against Anderssen, probably the second strongest player in the world at that time, and beat_him by 5-2. Following this victory, he was invited to take part in the 1872 London Tournament. He came 3rd and, probably because he was disappointed at his result, immediately challenged – the winner, Steinitz, to a match for the title of World Champion. Steinitz had claimed this title after his victory over Anderssen in 1866. Zukertort lost the match by + 1 -7 :4.

Meanwhile, Zukertort had decided to make England his permanent home and became a naturalised Englishman in l878.

Zukertort tied with Anderssen for 2nd prize in a master tournament in Leipzig in 1877, but his first major international event was Paris 1878, when he tied for lst place with Winawer and won the play-oft. In 1880 he beat the French champion, Rosenthal, in a match 7-1, and the following year he beat Blackburne +7 -2 – 5. The greatest performance of his career came in 1883, when in the London Tournament he won lst prize, three points ahead of Steinitz, who came 2nd. His victory was certain two weeks before the end of the tournament when he had a score of 22 out of 23. With victory secure, he went on to lose his last three games, the strain having proved too much.

Zukertort was advised by his doctor to give up serious chess but he refused and within a short time left England for a chess tour of the United States, Canada and Europe. On his return from this tour, he left almost immediately to play a second match for the world title against Steinitz. This took place in 1886. Zukertort was in no fit state of health

for such a match, and it proved too much for him. He lost by +5 -10 =5 and returned to England a physical and nervous wreck.

Zukertort never fully recovered. He continued to play chess, but with little success. He died at Charing Cross Hospital on 20th June 1888 of cerebral haemorrhage, following a game at Simpson’s ‘Divan’.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

“One of the most talented players of all time and possibly an English Prussian Polish Jewish grandmaster, the antecedents and early career of Zukertort are shrouded in mystery, a mystery that was the more complete in that the only account of these comes from Zukertort with a lack of corroboration so great that perhaps he really was telling the truth. Whatever the truth may be it is certain that he was a great chess player, one of those who carry with them the aura of certain genius. According to Zukertort, then, he was born in Lublin of mixed Prussian and Polish descent and his mother was the Baroness Krzyzanovska. The name of his mother sounds incredibly like an invention of W. C. Fields and it is difficult to believe that his father’s name, Zukertort, was not Jewish.

Again according to Zukertort he studied chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, claiming to have obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University. His versatility was astonishing. He spoke nine languages including Hebrew and was acquainted with several more. He had been a soldier, having fought in several campaigns for Prussia against Austria, Denmark and France; and once had been left for dead on the battlefield.

A music critic, editor of a political paper, on the staff of Bismarck’s newspaper, the Allgemeine Zeitung; gifted with a memory so colossal that he never forgot a game he played; a consummate fencer, a blindfold simultaneous player of undoubted repute (he had played as many as fifteen simultaneously blindfold) and a grandmaster with justified pretensions towards the world title: most of these attributes we have to take on Zukertort’s word. But there is enough left that is substantiated to show his great importance in the history of chess.

His early chess career had much to do with Anderssen whom he beat in a match, when Anderssen had grown old, in 1871 in Germany by +5-2, having lost a previous match to him in Berlin in 1868 by +3 -8 =1. On the strength of his win over Anderssen in the second match he was invited to play in a small but strong tournament in London in 1872 where he came 3rd below Steinitz and Blackburne. Immediately afterwards he played a match with Steinitz in which he was overwhelmingly defeated by +1-7 =4.It is unlikely that this was for the World Championship since no mention was made of the title at the time and the stakes were small, £2O for the winner and £l0 for the loser.

Despite this disastrous loss, which contained the seeds of further disasters, Zukertort felt that London was his true home and decided to stay in England, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1878. His results in tournament and match play from then on showed a steep upward curve. He was 2nd in London 1876, lst in a small tournament in Cologne 1877 and :2nd at Leipzis that year. He came lst in a big tournament at Paris 1878 where he tied with Winawer and won the play-off.

In 1880 he won a match in London against Rosenthal by +7 -l =11 and in the following year he was 2nd to Blackburne in Berlin. He was no less than 3 points behind Blackburne but he avenged this by beating him in a match in London the same year by +7 -2 =5.

A comparative setback came in a great tournament at Vienna in 1882 when he tied for fourth place with Mackenzie, below Steinitz, Winawer and Mason but in 1883 came the peak of his career when

he won lst prize in the great London tournament, 3 points ahead of Steinitz and 5.5 points ahead of Blackburne who came 3rd.

The remarkable nature of his victory is to be seen from the fact that he was sure of first prize with some two weeks still to go when he had a score of 22/23. But, ominously, his health was giving way and he had been sustaining himself by the use of drugs. He lost his last three games. It is very probable that this high point in his career was also the time when his health began to deteriorate under the excessive nervous strains by his conscious efforts to out rival Steinitz.

Thus, though he had been warned by his doctor he refused to abandon serious play and in 1886 he played his match for the World Championship against Steinitz in the USA, losing by +S -10 =5. The strain was this time too great an and he returned to England with his health completely shattered.

This was reflected in his subsequent results. =7th in London 1886 and =3rd in a smaller tournament at Nottingham that year, he had disastrous results throughout 1887: =l5th at Frankfurt-am-Main, 4th in a small tournament in London and a match loss there to Blackburne by +1-5:8.

In the last year of his life he was =7th in London in 1888 playing to the last possible moment, he died from a cerebral haemorrhage after a game at Simpson’s Divan.

Despite a career that stopped as if it were halfway, Zukertort is clearly one of the chess immortals and there is about his best game a sort of resilient and shining splendour that no other player possesses.”

Zukertort was buried in the Brompton Cemetry. He are details.

The grave was rededicated in 2012 thanks to the efforts of many chess enthusiasts.

Several opening variations have been named after Zukertort :

The Zukertort Defence in the Vienna Game, a variation advocated by Zukertort from 1871.

After 6 exd5 Bg4T 7 Nf3 Black castles, sacrificing a piece for counterattack :

The Zukertort Opening, 1.Nf3 abhorred by Ruy Lopez, used by Zukertort always as a preliminary

to 2.d4, now the fourth most popular opening move, after 1.e4, 1.d4, and 1 c4.

The Zukertort variation, in the Spanish opening, favoured by Zukertort in the 1880s :

but laid to rest soon after.

The Zukertort Variation in the Philidor Defence :

Possibly the Colle-Zukertort Opening is the most well-known

and still continues to be written about to this day.

He was inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2016.

Here is an interesting article from the ruchess web site.

Dominic Lawson wrote this article in 2014.

An interesting article from chess.com

Here is his Wikipedia entry

BCN Remembers Johannes Hermann Zukertort (07-ix-1842 20-vi-1888)

From the July 2012 editorial in British Chess Magazine we had this report :

“Johann Hermann Zukertort’s (1842-1888) grave was rededicated last month in London’s crowded Brompton Cemetery, largely thanks to an initiative led by Stuart Conquest. The resting place of one of the leading players of the nineteenth century was recorded but the grave had fallen into terrible dis-repair. See BCM 1888, pp.307-8 and p.338-340 for the obituary of the great man. We read that his death ‘was terribly sudden’, that he was buried on 26th June, 1888 and that ‘several pretty wreaths were laid on the coffin …’”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

Polish-born Jew, from about 1871 to 1886 second player in the world after Steinitz. From about 1862 to 1866 Zukertort, then living in Breslau, played many friendly games with Anderssen, at first receiving odds of a knight but soon meeting on even terms. They played two matches in Berlin, Zukertort losing the first in 1868 (+3 = 1—8) and winning the second in 1871 (+5 — 2).

In 1872 a group of London players, anxious to find someone who could defeat Steinitz, paid Zukertort 20 guineas to come to England. He came, he stayed, but he failed to beat Steinitz.

Zukertort took third place after Steinitz and Blackburne at London 1872, the strongest tournament in which He had yet played, and later in the year was decisively beaten by Steinitz in match play ( + 1=4—7). Zukertort settled in London as a professional player.

He won matches against Potter in 1872 ( + 4=8—2), Rosentalis in 1880 ( + 7=11-1), and Blackburne in 1881 ( + 7=5-2), He also had a fair record in tournament play: Leipzig 1877, second equal with Anderssen after L. Paulsen ahead of Winawer:-* Paris 1878, first ( + 14=5—3) equal with Winawer ahead of Blackburne (Zukertort won the play-off, +2=2); Berlin 1881, second alter Blackburne ahead of Winawer; and Vienna 1882, fourth equal with Mackenzie after Steinitz, Winawer, and Mason.

The world’s nine best players were among the competitors in the double-round London tournament of 1883 when Zukertort achieved his greatest victory: first prize (+22—4) three points ahead of Steinitz, the second prize winner, in seven weeks and a day he played 33 games (seven draws were replayed) and towards the end he relieved the strain by taking opiates, the cause of his losing his last three games. This victory led to the first match for the world championship, a struggle between him and Steinitz, USA, 1886. After nearly ten weeks of relentless pressure by his opponent Zukertort lost (- 1 – 5=5 —10) i winning only one of the last 15 games. His spirit crushed, his health failing, he was advised to give up competitive chess, but there was nothing else he could do. I am prepared, he said, l to be taken away at any moment.’ Seized by a stroke while playing at London’s famous coffee-house, Simpson’s Divan, he died the next day.

Like Anderssen, his teacher, Zukertort had a direct and straightforward style, and in combinative situations he could calculate far ahead. Having a prodigious memory he could recollect at will countless games and opening variations, a talent which may have limited his vision. (For his match with Steinitz in 1872 his extensive opening preparations brought him only one win. Steinitz was the better player in unfamiliar situations.) As an annotator and analyst Zukertort was outstanding in his time, and much of his work in these fields appeared in the Chess Monthly which he and Hoffer edited from 1879 to 1888.

Zukertort read widely and what he read became, as he said ‘iron-printed in my head’. Hoffer recalls Zukertort holding a visitor from India spellbound with a convincing and detailed account of a tiger-hunt, although it must have been outside his experience. Zukertort’s own account of his early life was reported in the Norfolk News, 16 Nov. 1872, He claimed aristocratic (Prussian and Polish) descent, and fluency in nine languages. “He learnt one language to read Dante, another to read Cervantes, and a third, Sanskrit, to trace the origin of chess,’ Besides the study of theology, philology, and social science he is also an original thinker on some of the problems that perplex humanity , ” He is ‘an accomplished swordsman, the best domino player in Berlin, one of the best whist players living, and so good a pistol shot that at fifteen paces he is morally certain to hit the ace of hearts . , , has found time to play 6,000 games of chess with Anderssen alone … a pupil of Moscheles, and in 1862-6 musical critic of the first journal in Silesia … is also a military veteran … he served in the Danish, in the Austrian, and in the French campaign , , , he was present at the following engagements, viz, in Denmark, Missunde, Duppcl, and Alsen; in Austria, Trauienau, Koniginhof, Kdniggratz (Sadowa), and Blumcnau; in France, Spicheeren, Pange (Vionville), Gravelotte, Noisevillc, and all other affairs before Metz, Twice dangerously wounded, and once left for dead upon the field, he is entitled to wear seven medals besides the orders of the Red Eagle and the Iron Cross, . . . He obtained the degree of M.D. at Breslau in 1865, having chiefly devoted his attention to chemistry under Professor Bunsen at Heidelberg, and to physiology at Berlin under Professor Virchow … is now on the staff of Prince Bismarck’s private organ, the Allgemeine Zetiling, and is chief editor of a political journal which receives “officios’” from the Government at Berlin. He is . . . the author of the Grosses Schach Handbuck and a Leitfaden , and , . . was for several years editor of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung. ’ There is some truth in the last sentence: he was co-author of the books, co-editor of the chess magazine.

A. Olson, J. H. Zukertort (1912) is a collection of 201 games with Swedish text.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks

“One of the leading players of the last century, Zukertort was born in Riga on 7th September 1842. His father was a Prussian and his mother a Pole. When he was 13, his family moved to Breslau. After studying chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, he obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University in 1865. He served as a doctor with the Prussian Army during his country’s wars against Denmark, Austria and France and was decorated for gallantry.

Zukertort was a man of many talents. He had a prodigious memory, and it was said that he never forgot a game he had played. He spoke 11 languages, and he was an excellent pistol shot and fencer but it was journalism and chess that he chose for a career.

Zukertort learned to play chess when he was 18, and two years later he met Anderssen and became his pupil. Within three years he had become one of the strongest players in North Germany. He first drew attention to himself as a blindfold simultaneous player. In 1868, he gave a simultaneous blindfold display against seven players in Berlin. This was his first blindfold performan@, and it was so successful that he gave several further performances, almost immediately increasing the number of his opponents to 12.

Between 1867 and 1871, he was joint editor with Anderssen of the Neue Berliner Schachzeityng. In 1871 he played a match against Anderssen, probably the second strongest player in the world at that time, and beat_him by 5-2. Following this victory, he was invited to take part in the 1872 London Tournament. He came 3rd and, probably because he was disappointed at his result, immediately challenged – the winner, Steinitz, to a match for the title of World Champion. Steinitz had claimed this title after his victory over Anderssen in 1866. Zukertort lost the match by + 1 -7 :4.

Meanwhile, Zukertort had decided to make England his permanent home and became a naturalised Englishman in l878.

Zukertort tied with Anderssen for 2nd prize in a master tournament in Leipzig in 1877, but his first major international event was Paris 1878, when he tied for lst place with Winawer and won the play-oft. In 1880 he beat the French champion, Rosenthal, in a match 7-1, and the following year he beat Blackburne +7 -2 – 5. The greatest performance of his career came in 1883, when in the London Tournament he won lst prize, three points ahead of Steinitz, who came 2nd. His victory was certain two weeks before the end of the tournament when he had a score of 22 out of 23. With victory secure, he went on to lose his last three games, the strain having proved too much.

Zukertort was advised by his doctor to give up serious chess but he refused and within a short time left England for a chess tour of the United States, Canada and Europe. On his return from this tour, he left almost immediately to play a second match for the world title against Steinitz. This took place in 1886. Zukertort was in no fit state of health

for such a match, and it proved too much for him. He lost by +5 -10 =5 and returned to England a physical and nervous wreck.

Zukertort never fully recovered. He continued to play chess, but with little success. He died at Charing Cross Hospital on 20th June 1888 of cerebral haemorrhage, following a game at Simpson’s ‘Divan’.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

“One of the most talented players of all time and possibly an English Prussian Polish Jewish grandmaster, the antecedents and early career of Zukertort are shrouded in mystery, a mystery that was the more complete in that the only account of these comes from Zukertort with a lack of corroboration so great that perhaps he really was telling the truth. Whatever the truth may be it is certain that he was a great chess player, one of those who carry with them the aura of certain genius. According to Zukertort, then, he was born in Lublin of mixed Prussian and Polish descent and his mother was the Baroness Krzyzanovska. The name of his mother sounds incredibly like an invention of W. C. Fields and it is difficult to believe that his father’s name, Zukertort, was not Jewish.

Again according to Zukertort he studied chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, claiming to have obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University. His versatility was astonishing. He spoke nine languages including Hebrew and was acquainted with several more. He had been a soldier, having fought in several campaigns for Prussia against Austria, Denmark and France; and once had been left for dead on the battlefield.

A music critic, editor of a political paper, on the staff of Bismarck’s newspaper, the Allgemeine Zeitung; gifted with a memory so colossal that he never forgot a game he played; a consummate fencer, a blindfold simultaneous player of undoubted repute (he had played as many as fifteen simultaneously blindfold) and a grandmaster with justified pretensions towards the world title: most of these attributes we have to take on Zukertort’s word. But there is enough left that is substantiated to show his great importance in the history of chess.

His early chess career had much to do with Anderssen whom he beat in a match, when Anderssen had grown old, in 1871 in Germany by +5-2, having lost a previous match to him in Berlin in 1868 by +3 -8 =1. On the strength of his win over Anderssen in the second match he was invited to play in a small but strong tournament in London in 1872 where he came 3rd below Steinitz and Blackburne. Immediately afterwards he played a match with Steinitz in which he was overwhelmingly defeated by +1-7 =4.It is unlikely that this was for the World Championship since no mention was made of the title at the time and the stakes were small, £2O for the winner and £l0 for the loser.

Despite this disastrous loss, which contained the seeds of further disasters, Zukertort felt that London was his true home and decided to stay in England, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1878. His results in tournament and match play from then on showed a steep upward curve. He was 2nd in London 1876, lst in a small tournament in Cologne 1877 and :2nd at Leipzis that year. He came lst in a big tournament at Paris 1878 where he tied with Winawer and won the play-off.

In 1880 he won a match in London against Rosenthal by +7 -l =11 and in the following year he was 2nd to Blackburne in Berlin. He was no less than 3 points behind Blackburne but he avenged this by beating him in a match in London the same year by +7 -2 =5.

A comparative setback came in a great tournament at Vienna in 1882 when he tied for fourth place with Mackenzie, below Steinitz, Winawer and Mason but in 1883 came the peak of his career when

he won lst prize in the great London tournament, 3 points ahead of Steinitz and 5.5 points ahead of Blackburne who came 3rd.

The remarkable nature of his victory is to be seen from the fact that he was sure of first prize with some two weeks still to go when he had a score of 22/23. But, ominously, his health was giving way and he had been sustaining himself by the use of drugs. He lost his last three games. It is very probable that this high point in his career was also the time when his health began to deteriorate under the excessive nervous strains by his conscious efforts to out rival Steinitz.

Thus, though he had been warned by his doctor he refused to abandon serious play and in 1886 he played his match for the World Championship against Steinitz in the USA, losing by +S -10 =5. The strain was this time too great an and he returned to England with his health completely shattered.

This was reflected in his subsequent results. =7th in London 1886 and =3rd in a smaller tournament at Nottingham that year, he had disastrous results throughout 1887: =l5th at Frankfurt-am-Main, 4th in a small tournament in London and a match loss there to Blackburne by +1-5:8.

In the last year of his life he was =7th in London in 1888 playing to the last possible moment, he died from a cerebral haemorrhage after a game at Simpson’s Divan.

Despite a career that stopped as if it were halfway, Zukertort is clearly one of the chess immortals and there is about his best game a sort of resilient and shining splendour that no other player possesses.”

Zukertort was buried in the Brompton Cemetry. He are details.

The grave was rededicated in 2012 thanks to the efforts of many chess enthusiasts.

Several opening variations have been named after Zukertort :

The Zukertort Defence in the Vienna Game, a variation advocated by Zukertort from 1871.

After 6 exd5 Bg4T 7 Nf3 Black castles, sacrificing a piece for counterattack :

The Zukertort Opening, 1.Nf3 abhorred by Ruy Lopez, used by Zukertort always as a preliminary

to 2.d4, now the fourth most popular opening move, after 1.e4, 1.d4, and 1 c4.

The Zukertort variation, in the Spanish opening, favoured by Zukertort in the 1880s :

but laid to rest soon after.

The Zukertort Variation in the Philidor Defence :

Possibly the Colle-Zukertort Opening is the most well-known

and still continues to be written about to this day.

He was inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2016.

Here is an interesting article from the ruchess web site.

Dominic Lawson wrote this article in 2014.

An interesting article from chess.com

Here is his Wikipedia entry

BCN Remembers Johannes Hermann Zukertort (07-ix-1842 20-vi-1888)

From the July 2012 editorial in British Chess Magazine we had this report :

“Johann Hermann Zukertort’s (1842-1888) grave was rededicated last month in London’s crowded Brompton Cemetery, largely thanks to an initiative led by Stuart Conquest. The resting place of one of the leading players of the nineteenth century was recorded but the grave had fallen into terrible dis-repair. See BCM 1888, pp.307-8 and p.338-340 for the obituary of the great man. We read that his death ‘was terribly sudden’, that he was buried on 26th June, 1888 and that ‘several pretty wreaths were laid on the coffin …’”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

Polish-born Jew, from about 1871 to 1886 second player in the world after Steinitz. From about 1862 to 1866 Zukertort, then living in Breslau, played many friendly games with Anderssen, at first receiving odds of a knight but soon meeting on even terms. They played two matches in Berlin, Zukertort losing the first in 1868 (+3 = 1—8) and winning the second in 1871 (+5 — 2).

In 1872 a group of London players, anxious to find someone who could defeat Steinitz, paid Zukertort 20 guineas to come to England. He came, he stayed, but he failed to beat Steinitz.

Zukertort took third place after Steinitz and Blackburne at London 1872, the strongest tournament in which He had yet played, and later in the year was decisively beaten by Steinitz in match play ( + 1=4—7). Zukertort settled in London as a professional player.

He won matches against Potter in 1872 ( + 4=8—2), Rosentalis in 1880 ( + 7=11-1), and Blackburne in 1881 ( + 7=5-2), He also had a fair record in tournament play: Leipzig 1877, second equal with Anderssen after L. Paulsen ahead of Winawer:-* Paris 1878, first ( + 14=5—3) equal with Winawer ahead of Blackburne (Zukertort won the play-off, +2=2); Berlin 1881, second alter Blackburne ahead of Winawer; and Vienna 1882, fourth equal with Mackenzie after Steinitz, Winawer, and Mason.

The world’s nine best players were among the competitors in the double-round London tournament of 1883 when Zukertort achieved his greatest victory: first prize (+22—4) three points ahead of Steinitz, the second prize winner, in seven weeks and a day he played 33 games (seven draws were replayed) and towards the end he relieved the strain by taking opiates, the cause of his losing his last three games. This victory led to the first match for the world championship, a struggle between him and Steinitz, USA, 1886. After nearly ten weeks of relentless pressure by his opponent Zukertort lost (- 1 – 5=5 —10) i winning only one of the last 15 games. His spirit crushed, his health failing, he was advised to give up competitive chess, but there was nothing else he could do. I am prepared, he said, l to be taken away at any moment.’ Seized by a stroke while playing at London’s famous coffee-house, Simpson’s Divan, he died the next day.

Like Anderssen, his teacher, Zukertort had a direct and straightforward style, and in combinative situations he could calculate far ahead. Having a prodigious memory he could recollect at will countless games and opening variations, a talent which may have limited his vision. (For his match with Steinitz in 1872 his extensive opening preparations brought him only one win. Steinitz was the better player in unfamiliar situations.) As an annotator and analyst Zukertort was outstanding in his time, and much of his work in these fields appeared in the Chess Monthly which he and Hoffer edited from 1879 to 1888.

Zukertort read widely and what he read became, as he said ‘iron-printed in my head’. Hoffer recalls Zukertort holding a visitor from India spellbound with a convincing and detailed account of a tiger-hunt, although it must have been outside his experience. Zukertort’s own account of his early life was reported in the Norfolk News, 16 Nov. 1872, He claimed aristocratic (Prussian and Polish) descent, and fluency in nine languages. “He learnt one language to read Dante, another to read Cervantes, and a third, Sanskrit, to trace the origin of chess,’ Besides the study of theology, philology, and social science he is also an original thinker on some of the problems that perplex humanity , ” He is ‘an accomplished swordsman, the best domino player in Berlin, one of the best whist players living, and so good a pistol shot that at fifteen paces he is morally certain to hit the ace of hearts . , , has found time to play 6,000 games of chess with Anderssen alone … a pupil of Moscheles, and in 1862-6 musical critic of the first journal in Silesia … is also a military veteran … he served in the Danish, in the Austrian, and in the French campaign , , , he was present at the following engagements, viz, in Denmark, Missunde, Duppcl, and Alsen; in Austria, Trauienau, Koniginhof, Kdniggratz (Sadowa), and Blumcnau; in France, Spicheeren, Pange (Vionville), Gravelotte, Noisevillc, and all other affairs before Metz, Twice dangerously wounded, and once left for dead upon the field, he is entitled to wear seven medals besides the orders of the Red Eagle and the Iron Cross, . . . He obtained the degree of M.D. at Breslau in 1865, having chiefly devoted his attention to chemistry under Professor Bunsen at Heidelberg, and to physiology at Berlin under Professor Virchow … is now on the staff of Prince Bismarck’s private organ, the Allgemeine Zetiling, and is chief editor of a political journal which receives “officios’” from the Government at Berlin. He is . . . the author of the Grosses Schach Handbuck and a Leitfaden , and , . . was for several years editor of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung. ’ There is some truth in the last sentence: he was co-author of the books, co-editor of the chess magazine.

A. Olson, J. H. Zukertort (1912) is a collection of 201 games with Swedish text.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks

“One of the leading players of the last century, Zukertort was born in Riga on 7th September 1842. His father was a Prussian and his mother a Pole. When he was 13, his family moved to Breslau. After studying chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, he obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University in 1865. He served as a doctor with the Prussian Army during his country’s wars against Denmark, Austria and France and was decorated for gallantry.

Zukertort was a man of many talents. He had a prodigious memory, and it was said that he never forgot a game he had played. He spoke 11 languages, and he was an excellent pistol shot and fencer but it was journalism and chess that he chose for a career.

Zukertort learned to play chess when he was 18, and two years later he met Anderssen and became his pupil. Within three years he had become one of the strongest players in North Germany. He first drew attention to himself as a blindfold simultaneous player. In 1868, he gave a simultaneous blindfold display against seven players in Berlin. This was his first blindfold performan@, and it was so successful that he gave several further performances, almost immediately increasing the number of his opponents to 12.

Between 1867 and 1871, he was joint editor with Anderssen of the Neue Berliner Schachzeityng. In 1871 he played a match against Anderssen, probably the second strongest player in the world at that time, and beat_him by 5-2. Following this victory, he was invited to take part in the 1872 London Tournament. He came 3rd and, probably because he was disappointed at his result, immediately challenged – the winner, Steinitz, to a match for the title of World Champion. Steinitz had claimed this title after his victory over Anderssen in 1866. Zukertort lost the match by + 1 -7 :4.

Meanwhile, Zukertort had decided to make England his permanent home and became a naturalised Englishman in l878.

Zukertort tied with Anderssen for 2nd prize in a master tournament in Leipzig in 1877, but his first major international event was Paris 1878, when he tied for lst place with Winawer and won the play-oft. In 1880 he beat the French champion, Rosenthal, in a match 7-1, and the following year he beat Blackburne +7 -2 – 5. The greatest performance of his career came in 1883, when in the London Tournament he won lst prize, three points ahead of Steinitz, who came 2nd. His victory was certain two weeks before the end of the tournament when he had a score of 22 out of 23. With victory secure, he went on to lose his last three games, the strain having proved too much.

Zukertort was advised by his doctor to give up serious chess but he refused and within a short time left England for a chess tour of the United States, Canada and Europe. On his return from this tour, he left almost immediately to play a second match for the world title against Steinitz. This took place in 1886. Zukertort was in no fit state of health

for such a match, and it proved too much for him. He lost by +5 -10 =5 and returned to England a physical and nervous wreck.

Zukertort never fully recovered. He continued to play chess, but with little success. He died at Charing Cross Hospital on 20th June 1888 of cerebral haemorrhage, following a game at Simpson’s ‘Divan’.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

“One of the most talented players of all time and possibly an English Prussian Polish Jewish grandmaster, the antecedents and early career of Zukertort are shrouded in mystery, a mystery that was the more complete in that the only account of these comes from Zukertort with a lack of corroboration so great that perhaps he really was telling the truth. Whatever the truth may be it is certain that he was a great chess player, one of those who carry with them the aura of certain genius. According to Zukertort, then, he was born in Lublin of mixed Prussian and Polish descent and his mother was the Baroness Krzyzanovska. The name of his mother sounds incredibly like an invention of W. C. Fields and it is difficult to believe that his father’s name, Zukertort, was not Jewish.

Again according to Zukertort he studied chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, claiming to have obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University. His versatility was astonishing. He spoke nine languages including Hebrew and was acquainted with several more. He had been a soldier, having fought in several campaigns for Prussia against Austria, Denmark and France; and once had been left for dead on the battlefield.

A music critic, editor of a political paper, on the staff of Bismarck’s newspaper, the Allgemeine Zeitung; gifted with a memory so colossal that he never forgot a game he played; a consummate fencer, a blindfold simultaneous player of undoubted repute (he had played as many as fifteen simultaneously blindfold) and a grandmaster with justified pretensions towards the world title: most of these attributes we have to take on Zukertort’s word. But there is enough left that is substantiated to show his great importance in the history of chess.

His early chess career had much to do with Anderssen whom he beat in a match, when Anderssen had grown old, in 1871 in Germany by +5-2, having lost a previous match to him in Berlin in 1868 by +3 -8 =1. On the strength of his win over Anderssen in the second match he was invited to play in a small but strong tournament in London in 1872 where he came 3rd below Steinitz and Blackburne. Immediately afterwards he played a match with Steinitz in which he was overwhelmingly defeated by +1-7 =4.It is unlikely that this was for the World Championship since no mention was made of the title at the time and the stakes were small, £2O for the winner and £l0 for the loser.

Despite this disastrous loss, which contained the seeds of further disasters, Zukertort felt that London was his true home and decided to stay in England, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1878. His results in tournament and match play from then on showed a steep upward curve. He was 2nd in London 1876, lst in a small tournament in Cologne 1877 and :2nd at Leipzis that year. He came lst in a big tournament at Paris 1878 where he tied with Winawer and won the play-off.

In 1880 he won a match in London against Rosenthal by +7 -l =11 and in the following year he was 2nd to Blackburne in Berlin. He was no less than 3 points behind Blackburne but he avenged this by beating him in a match in London the same year by +7 -2 =5.

A comparative setback came in a great tournament at Vienna in 1882 when he tied for fourth place with Mackenzie, below Steinitz, Winawer and Mason but in 1883 came the peak of his career when

he won lst prize in the great London tournament, 3 points ahead of Steinitz and 5.5 points ahead of Blackburne who came 3rd.

The remarkable nature of his victory is to be seen from the fact that he was sure of first prize with some two weeks still to go when he had a score of 22/23. But, ominously, his health was giving way and he had been sustaining himself by the use of drugs. He lost his last three games. It is very probable that this high point in his career was also the time when his health began to deteriorate under the excessive nervous strains by his conscious efforts to out rival Steinitz.

Thus, though he had been warned by his doctor he refused to abandon serious play and in 1886 he played his match for the World Championship against Steinitz in the USA, losing by +S -10 =5. The strain was this time too great an and he returned to England with his health completely shattered.

This was reflected in his subsequent results. =7th in London 1886 and =3rd in a smaller tournament at Nottingham that year, he had disastrous results throughout 1887: =l5th at Frankfurt-am-Main, 4th in a small tournament in London and a match loss there to Blackburne by +1-5:8.

In the last year of his life he was =7th in London in 1888 playing to the last possible moment, he died from a cerebral haemorrhage after a game at Simpson’s Divan.

Despite a career that stopped as if it were halfway, Zukertort is clearly one of the chess immortals and there is about his best game a sort of resilient and shining splendour that no other player possesses.”

Zukertort was buried in the Brompton Cemetry. He are details.

The grave was rededicated in 2012 thanks to the efforts of many chess enthusiasts.

Several opening variations have been named after Zukertort :

The Zukertort Defence in the Vienna Game, a variation advocated by Zukertort from 1871.

After 6 exd5 Bg4T 7 Nf3 Black castles, sacrificing a piece for counterattack :

The Zukertort Opening, 1.Nf3 abhorred by Ruy Lopez, used by Zukertort always as a preliminary

to 2.d4, now the fourth most popular opening move, after 1.e4, 1.d4, and 1 c4.

The Zukertort variation, in the Spanish opening, favoured by Zukertort in the 1880s :

but laid to rest soon after.

The Zukertort Variation in the Philidor Defence :

Possibly the Colle-Zukertort Opening is the most well-known

and still continues to be written about to this day.

He was inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2016.

Here is an interesting article from the ruchess web site.

Dominic Lawson wrote this article in 2014.

An interesting article from chess.com

Here is his Wikipedia entry