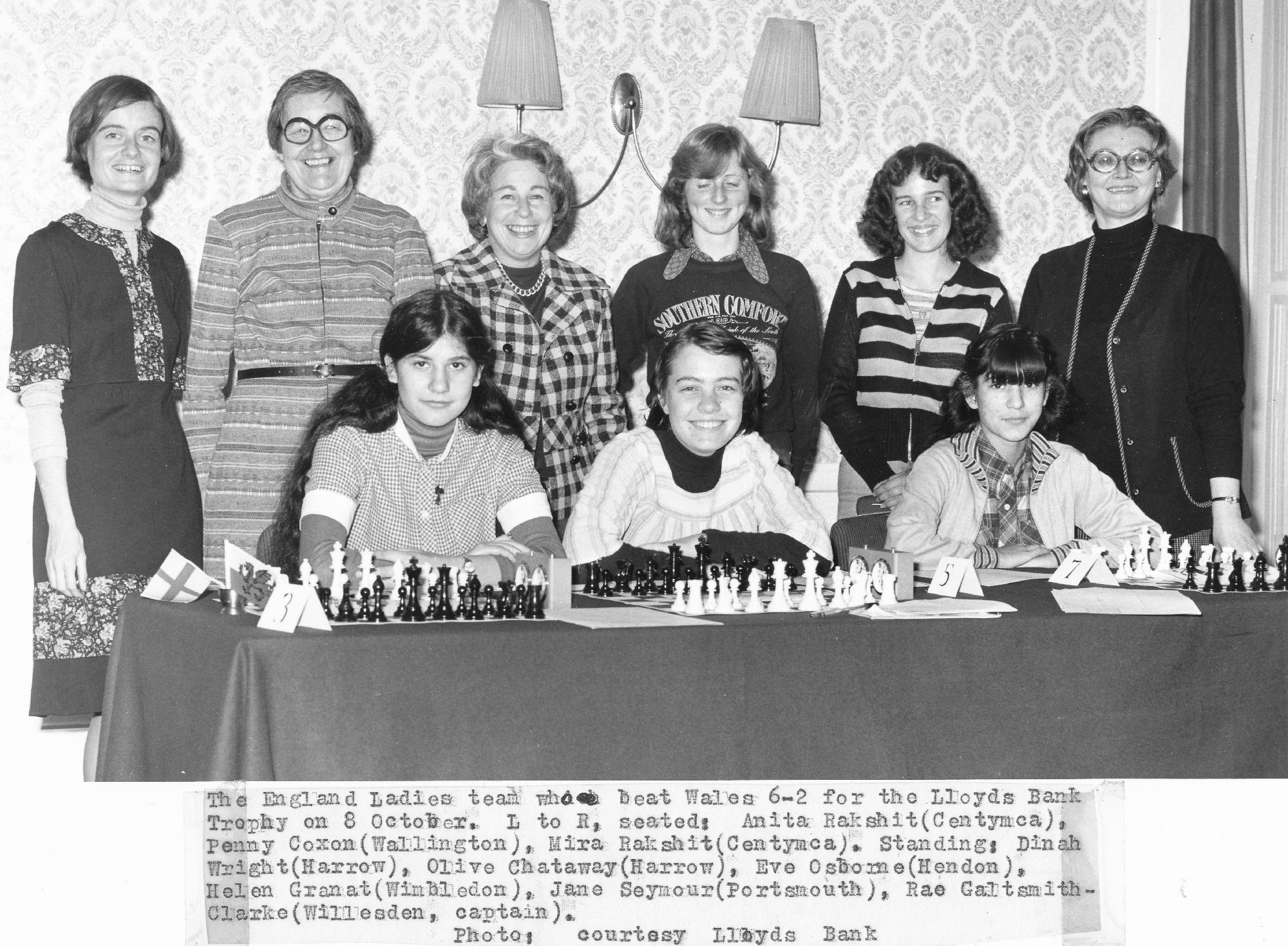

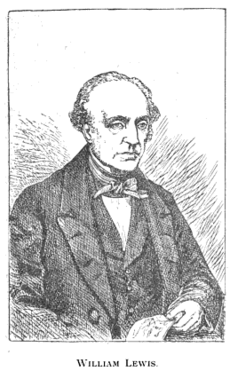

We note the passing today (August 22nd) in 1870 of William Lewis of the Lewis Counter Gambit.

From The Oxford Companion to Chess (OUP, 1984) by Hooper & Whyld :

“English player and author. He left his native Birmingham as a young man and worked for a time with a merchant in London. He learned much of his chess from Sarratt, a debt that was not repaid.

Around 1819 he was operator of the Turk, meeting all-comers successfully. With Cochrane he visited Paris in 1821, received odds of pawn and move from Deschapelles, and defeated him in a short match (+ 1=2), Lewis had already begun to write and of the more useful books he published around this time were translations of Greco and Carrera which appeared in 1819 and 1822 respectively. Although he considered Sarratt’s A Treatise on the Game of Chess (1808) a poorly written book, Lewis published a second edition in 1822 in direct competition with Sarratt’s last book, published in 1821 by his impoverished widow, (In 1843 many Englishmen contributed to a fund for Mrs Sarratt in her old age, Lewis’s name is not on the subscription list,}

In 1825 Bourdonnais visited England. Lewis recalled that they played about 70 games, and according to Walker seven of them constituted a

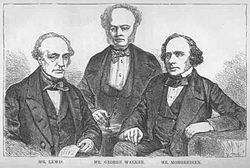

match which Lewis lost (+2—5). With no significant playing achievements to his credit Lewis acquired such a high reputation that a correspondent writing to the weekly magazine Bell’s Life in 1838 was moved to call him grandmaster.

From 1825 he preserved this reputation by the simplest means: he declined to play on even terms. In the same year he opened a club where he gave lessons at half a guinea each. McDonnell and Walker were among his pupils. Speculating unwisely on a piano-making patent, Lewis went bankrupt in 1827, and the club closed. After three precarious years of teaching chess (rich patrons were becoming fewer) Lewis became actuary of the Family Endowment Society and enjoyed financial security

for the rest of his life.

Circumstances now made it possible for him to concentrate on his writing and he published his two most important works: Series of Progressive Lessons (1831) and Second Series of Lessons (1832), both republished with various revisions. Lewis continued to write but gradually withdrew from other chess activities; his last notable connection with chess was as stakeholder for the Morphy-Lowenthal match of 1858.

Lewis’s Lessons contain extensive analyses of many opening variations, examined in the closeness of his study. Subsequent writers, notably Lasa, were influenced by these books, but more on account of the form than the content, which, adequate for the 1830s, were soon out of date.

Around 1840 writers no longer worked in isolation (a circumstance Lewis found unavoidable) and new positional ideas were being shaped. Because Lewis failed to assimilate these his judgements were faulty, and his voluminous Treatise on the Game of Chess (1844) was out of date when published.

Industrious rather than inventive, he made only one innovation, the Lewis Counter-Gambit; but it had no practical value in 1844, for simpler defences had already been discovered. Lewis’s work commands respect, but he is more aptly described as the last and one of the best of the ‘old’ writers than the first of the new, a more fitting description for Jaenisch and the authors of Bilguer’s Handbuch. ”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (Robert Hale, 1970 & 1976) by Anne Sunnucks :

Chess theoretician, teacher, author and one of the leading players in England in the nineteenth century.

William Lewis was born in Birmingham on 9th October 1787. As a young man he went to London and took chess lessons from JH Sarratt. Within a short time he was making chess his principal means of livelihood.

In 1819 he was engaged as the player concealed in the chess-playing automaton, ‘The Turk’, when it was exhibited in London. In 1825 he opened some chess rooms in St. Martin’s Lane in London, where he taught chess. Among his pupils was Alexander McDonnell. After going bankrupt in 1827, the chess rooms were closed, and Lewis decided to put his lessons into a book. He soon became a highly-successful writer, His Chessboard Companion published in 1838 ran into nine editions, and his Series of Progressive Lessons of the Game of Chess has been described as one of the landmarks in the history of the game. This book included some completely new analyses of various chess openings and later formed the basis of the Handbuch des Schachspiels. Lewis also translated the work of Greco and Stamma and was author of The Elements of Chess (1882), Fifty Games of Chess (1832) and Chess for Beginners (1835).

Towards the end of his life, Lewis rarely played chess, and his last public appearance in chess circles was 12 before he died, when he acted at stake-holder in the match between Morphy and Lowenthal in 1858. He died on 22nd August 1870.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977) by Harry Golombek :

“Author of The Chessboard Companion, London, 1838, and several other popular works on chess (including translations of Greco and Stamma). Lewis was also a leading chess teacher – his most famous pupil was Alexdander McDonnell – and for a time he ran chess rooms in St. Martin’s Lane. In 1819 he operated the chess-playing automaton ‘The Turk’ when it was exhibited in London. The Lewis Counter-Gambit is 1.P-K4, P-K4; 2.B-B4 B-B4; 3.P-QB3,P-Q5!?”

From “Chess : A History” by Harry Golombek there are two references to WL on pages 98 and 123 alluded to above.

Here is an interesting article from Chess.com

From Wikipedia :

“William Lewis (1787–1870) was an English chess player and author, nowadays best known for the Lewis Countergambit and for being the first player ever to be described as a Grandmaster of the game.[1]

Born in Birmingham, William Lewis moved as a young man to London where he worked for a merchant for a short period. He became a student of chess player Jacob Sarratt, but in later years he showed himself to be rather ungrateful towards his teacher.[1] Although he considered Sarratt’s Treatise on the Game of Chess (1808)[2] a “poorly written book”, in 1822 Lewis published a second edition of it three years after Sarratt’s death in direct competition with Sarratt’s own superior revision published posthumously in 1821 by Sarratt’s poverty-stricken widow. In 1843, many players contributed to a fund to help the old widow, but Lewis’ name is not on the list of subscribers.[1]

Around 1819 Lewis was the hidden player inside the Turk (a famous automaton), meeting all-comers successfully. He suggested to Johann Maelzel that Peter Unger Williams, a fellow ex-student of Sarratt, should be the next person to operate inside the machine. When P. U. Williams played a game against the Turk, Lewis recognised the old friend from his style of play (the operator could not see his opponents) and convinced Maelzel to reveal to Williams the secret of the Turk. Later, P. U. Williams himself took Lewis’ place inside the machine.[3]

Lewis visited Paris along with Scottish player John Cochrane in 1821, where they played with Alexandre Deschapelles, receiving the advantage of pawn and move. He won the short match (+1 =2).”

“Lewis’ career as an author began at this time, and included translations of the works of Greco and Carrera, published in 1819[5] and 1822[6] respectively.

He was the leading English player in the correspondence match between London and Edinburgh in 1824, won by the Scots (+2 = 2 -1). Later, he published a book on the match with analysis of the games.[7] In the period of 1834–36 he was also part of the Committee of the Westminster Chess Club, who played and lost (−2) the match by correspondence with the Paris Chess Club. The other players were his students McDonnell and Walker, while the French line up included Boncourt, Alexandre, St. Amant and Chamouillet.[8] When De La Bourdonnais visited England in 1825, Lewis played about 70 games with the French master. Seven of these games probably represented a match that Lewis lost (+2 -5).[9]

Lewis enjoyed a considerable reputation as a chess player in his time. A correspondent writing to the weekly magazine Bell’s Life in 1838 called him “our past grandmaster”, the first known use of the term in chess.[1] Starting from 1825 he preserved his reputation by the same means that Deschapelles used in France, by refusing to play anyone on even terms. In the same year Lewis founded a Chess Club where he gave lessons to, amongst others, Walker and McDonnell. He was declared bankrupt in 1827 due to bad investments on a patent for the construction of pianos and his chess club was forced to close. The next three years were quite difficult until in 1830 he got a job that assured him of solid financial security for the rest of his life. Thanks to this job, he could focus on writing his two major works: Series of Progressive Lessons (1831) and Second Series of Progressive Lessons (1832). The first series of the Lessons were more elementary in character, and designed for the use of beginners; the second series, on the other hand, went deeply into all the known openings. Here, for the first time we find the Evans Gambit, which is named after its inventor, Capt. Evans.[10]

The works of Lewis (together with his teacher Sarratt) were oriented towards the rethinking of the strictly Philidorian principles of play in favour of the Modenese school of Del Rio, Lolli and Ponziani.[11] When he realised that he could not give an advantage to the new generation of British players, Lewis withdrew gradually from active play[1] (in the same way that Deschapelles did after his defeat against De La Bourdonnais).

After his retirement he wrote other chess treatises, but his isolation prevented him from assimilating the positional ideas of the new generation of chess-players. For this reason, Hooper and Whyld in their Oxford Chess Companion describe the last voluminous work of Lewis, A Treatise on Chess (1844),[12] as already “out of date when published”.”