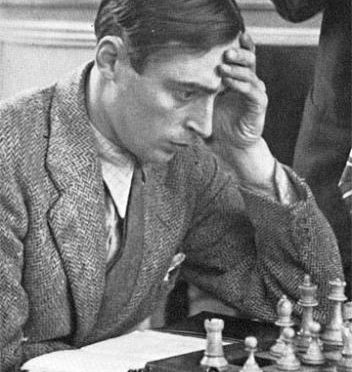

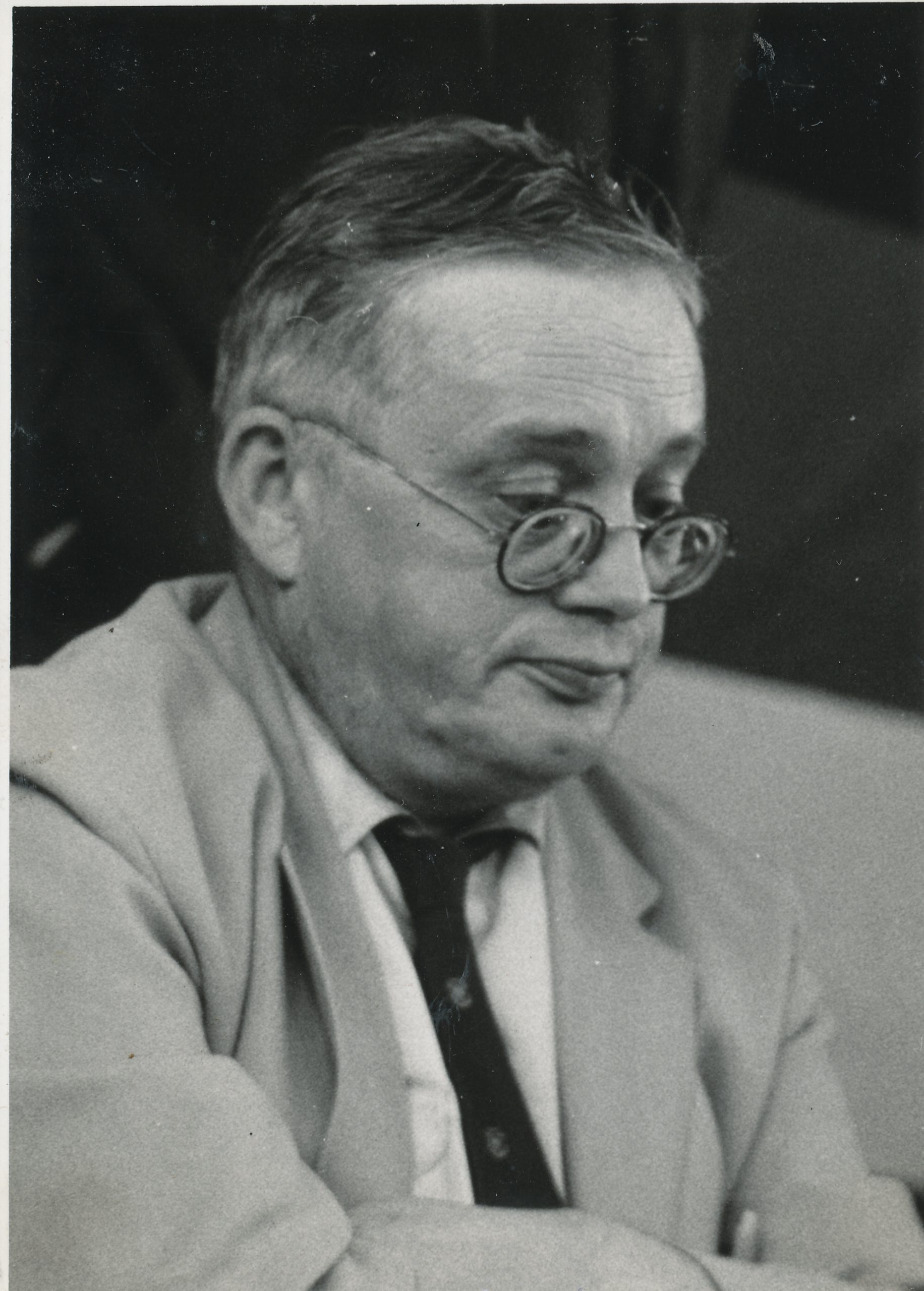

We remember Hugh Alexander who passed away on Friday, 15-ii-1974. The death was registered in the Borough of Cheltenham. Currently his burial / cremation site is unknown.

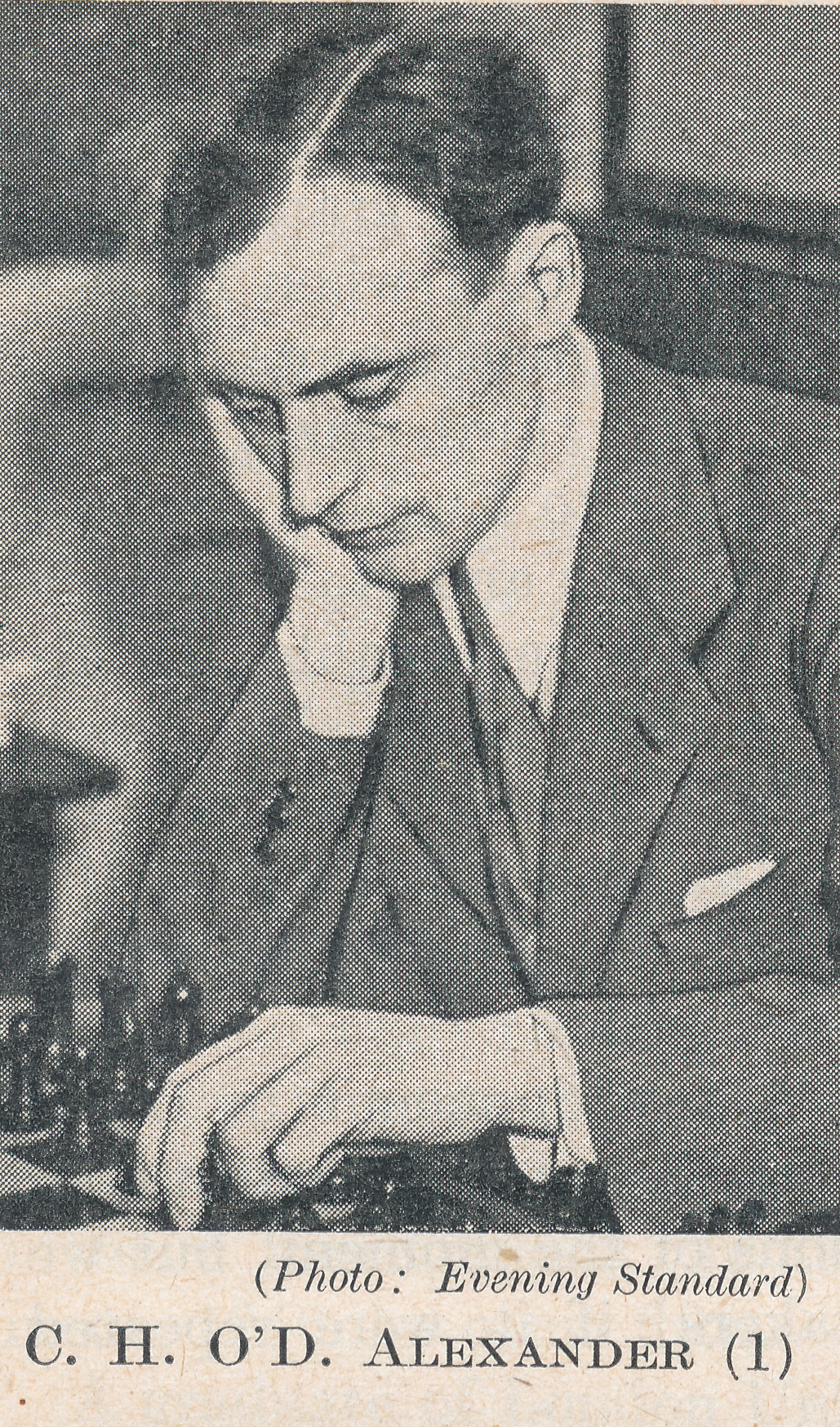

Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander was born on Monday, April 19th, 1909 in Cork, Munster, Republic of Ireland.

Hugh’s parents were Conel William Long Alexander (1879-1920) and Hilda Barbara Alexander (née Bennett) (1881-1964) who married in Hook Church, Hampshire. His father was a Professor of Civil Engineering from County Donegal and his mother was the daughter of a timber merchant and was from Birmingham.

Hugh’s father moved to Hook in Hampshire. At some point they returned to Cork and then relocated to Birmingham.

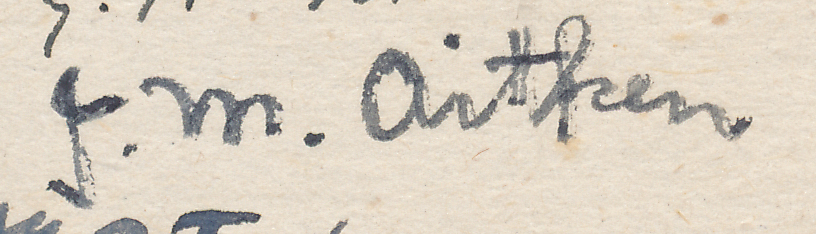

In the 1911 Irish census aged two Hugh was recorded as being a Presbyterian. The household consisted of his father, mother and two servants Maud McAuliffe (19) from County Cork and Johanna Hanlon (20) from Cork City all living at 20, Connaught Avenue, Cork.

At the time of the census all members of the household were capable of reading and writing apart from Hugh who was recorded as “cannot read”.

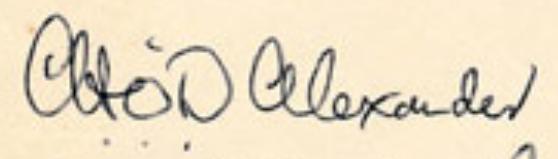

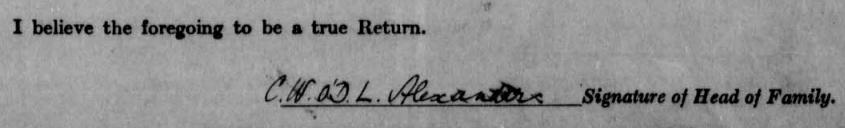

and Hugh’s father signed the Return as follows :

Hugh attended Londonderry College and then went to King Edward’s School, Birmingham.

Hugh married Enid Constance Rose Crichton Neate (1900-1982) in October 1934 and the marriage was registered in the district of Westminster, Middlesex.

According to Rodric Braithwaite :

“Enid, was an equally striking personality. She was descended from one of the defenders of the Eureka Stockade, the “birthplace of Australian democracy”. She was educated at the Sorbonne, a formidable dialectician, art historian and collector. In her later years she returned to Australia, where she was endlessly hospitable to passing Russian chessplayers, and to itinerant musicians, including my own father.”

Hugh and Enid had a son Michael (19 June 1936 – 1 June 2002) who became the foreign policy secretary to Margaret Thatcher and the UK ambassador to NATO. Here is Michael’s obituary.

Michael married Traute Krohn. Michael and Traute gave Hugh a grandson, Conel Alexander who is a Cosmochemist at the Earth and Planets Laboratory, Carnegie Institution for Science, Washington.

Staff Scientist

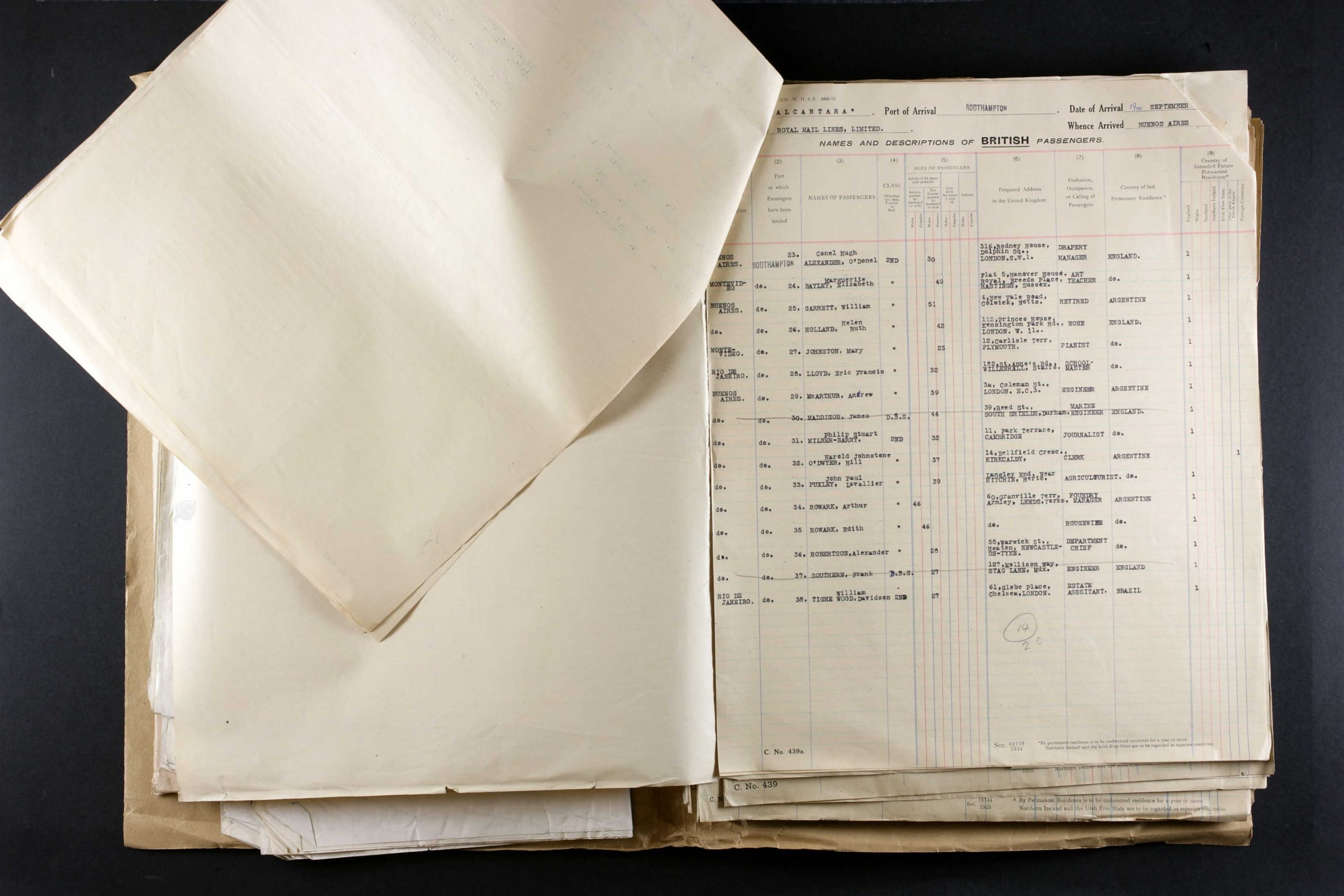

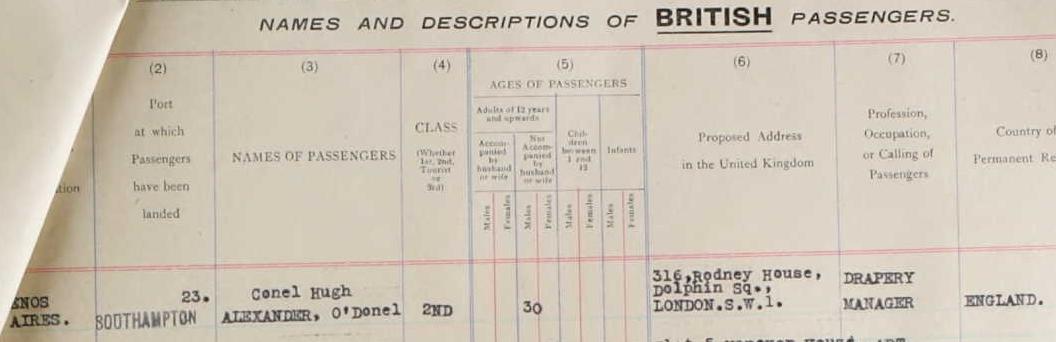

Prior to the second world war Alexander was officially employed by John Spedan Lewis in his Department store in Oxford Street. When he returned from Buenos Aires (“good air”) from the 1939 Olympiad he travelled aboard the RMS Alcantara. Here is the entry in the passenger list for September 19th, 1939 :

and here is Alexander’s entry in detail. Note that his occupation is described as “Drapery Manager” :

Hugh sailed from Buenos Aires, Argentina in September 1939 to arrive at Southampton September 19th 1939. The ship was the Alcantara operated by Royal Mail Lines Ltd hence the RMS Alcantara.

According to Wikipedia : “RMS Alcantara was a Royal Mail Lines ocean liner that was built in Belfast in 1926. She served in the Second World War first as an armed merchant cruiser and then a troop ship, was returned to civilian service in 1948 and scrapped in 1958.

Ports of the voyage were : Buenos Aires; Montevideo; Santos and Rio de Janeiro and Hugh’s official number was 148151 and he travelled 2nd class. His proposed destination residential address was

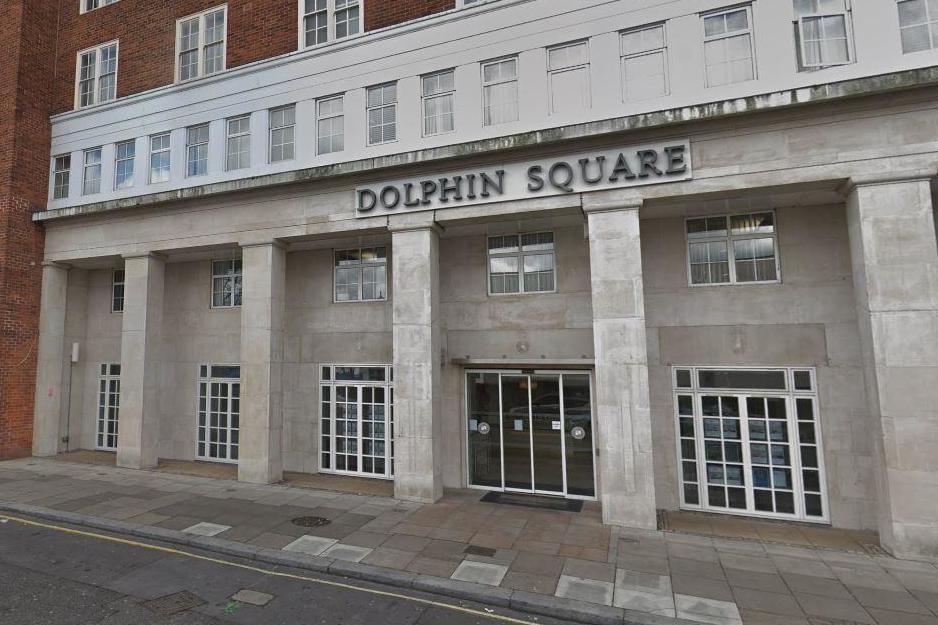

316, Rodney House, Dolphin Square, London, SW1

According to Wikipedia : “The proximity of Dolphin Square to the Palace of Westminster and the headquarters of the intelligence agencies MI5 (Thames House) and MI6 (Vauxhall Cross) has attracted many politicians, peers, civil servants and intelligence agency personnel as residents.”

There was some discussion of Drapery Manager in another place.

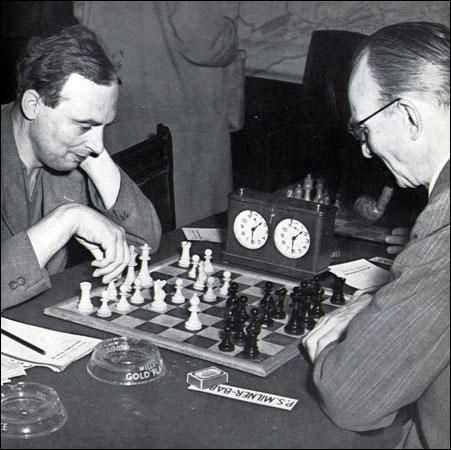

From British Chess Magazine, Volume XCIV (94, 1974), Number 4 (April), pp. 117-120 by PS Milner-Barry :

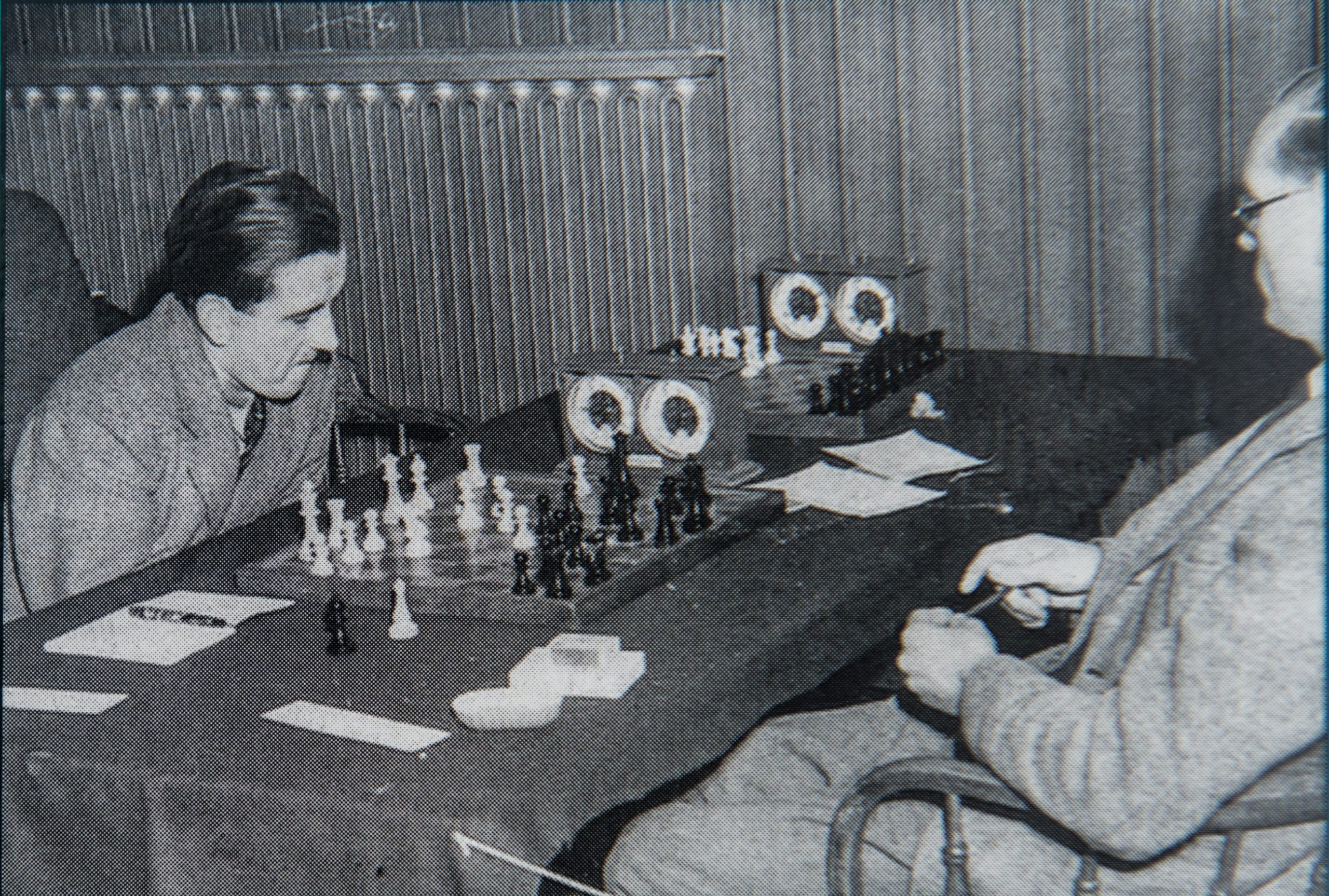

“A proper assessment of Hugh Alexander, who died on February 15th 1974 must await a later issue. But I think he might have been pleased to see our last game published, and I give the score of it below, with notes based on our usual analysis immediately after the game. Over the past 45 years, ever since he went to Cambridge, we played whenever opportunity offered serious games with clocks.

Before the war they were played mostly at my mother’s house in Cambridge, and after the war and my own marriage at our house in Blackheath. When he moved to Cheltenham the opportunities became fewer but no year ever passed without two or three such games, usually at Easter or Christmas.

Alexander always used to say, it was certainly true of me, that this was the kind of chess that he enjoyed most. The games were conducted with the utmost vigour, though not without a good deal of propaganda on both sides. I suppose he won in the proportion of about two to one, but the disparity in strength never became one-sided. Nearly all the games opened 1 P-K4, P-K4; he played the Lopez when I allowed him. (I usually played the Petroff or Philidor), and I played a mixture – in the early days the Vienna and latterly mostly the King’s Gambit. On the whole Black did better than White for both of us.

The only concession we made to advancing years was that latterly we contented ourselves with four hour sessions and 36 moves, instead of 40 in 5 hours. We thought we had done enough for honour by then, and the games were usually finished in the time.

Hugh stayed with us the weekend before Christmas, when this game was played. He looked ill, but he was very cheerful and as good company as ever. He loved a good argument, and as my family so too,- the evening meal was its usual lively affair! I am myself a man of peace, and intellectually lazy; so in deference to my feelings the argument was suspended, before it became too hot. I am afraid they all thought I was a spoil-sport. It was as happy a visit as any of us could remember and it is difficult to accept there will not be another.

As for the game, it was not one of our most exciting encounters. But it is quite an interesting one, and shows Hugh playing as

well as ever – certainly much too well for me. But then he usually did.”

Following PSMBs contribution, in the same obituary there was this from Harry Golombek :

C.H.O’D. Alexander and the ‘B.C.M.’

I have written elsewhere about Hugh Alexander both as a person and as a chess-player and I also intend to devote a forthcoming article in ‘The Times‘ on Saturday to an appraisal of his place in British Chess. Here, however, I would like to describe briefly his connection with this magazine over the years and to show how

important his help was to the progress of the ‘BCM‘.

In the years immediately preceding the Second World War, Ash Wheatcroft and I had made a determined effort to maintain and increase the role of the ‘BCM‘, he in a managerial capacity and I as its editor. With the coming of war and the departure of both of us into the army a sort of caretaker regime had to be provided. It worked as well as could have been expected but inevitably there had been a decline both in quality and financially. When peace came, the quality improved since it was possible to get more and better contributions but the financial aspect became almost alarming.

The question arose – was there a need for the magazine and if so how could that need be fulfilled with the fairly limited resources at hand. Some of us thought there was, but the ways and means were not so clear. Of all those who thought like this Alexander was the most effective in his approach to the problems. I know that from his very youth onwards he had been convinced of the importance of the ‘BCM’ to British chess and, being a practical idealist, when the

crisis came he set about dealing with it in the most expeditious way.

In November 1946 he became a director of the B.C.M. and continued in that position till February 1952, by which time the magazine had been set on a solid basis from

which it was unlikely to be shaken. It was his idea that Brian Reilly be asked to act as editor and almost his first act as director was to write a letter to him inviting him to become so. Then, in January 1947, he himself took over the editorship of the games department, an arduous task which he fulfilled with great competence and the utmost conscientiousness until May 1949 when the heavy work of the Civil Service department of which he was head compelled him to hand over the Games Section to me.

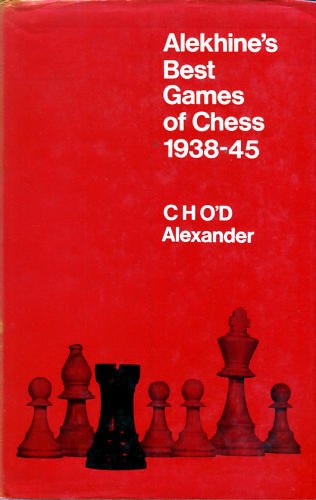

Before, however, that he gave up this post he, again in the most practical way possible, rendered the ‘BCM‘ another service. He wrote a book giving a selection of the games from the last period of Alekhine’s life and generously donated half the royalties to the ‘BCM‘ in order to bolster up its slender finances.

Even after he had to give up official connection with the magazine he retained a strong interest in its welfare. So, even though this recognition is belated and posthumous, I thought it was right to afford readers the possibility of joining with me in thanking High Alexander for all that he did in this respect in especial. At any rate, such matters should be on record for the chess historian.

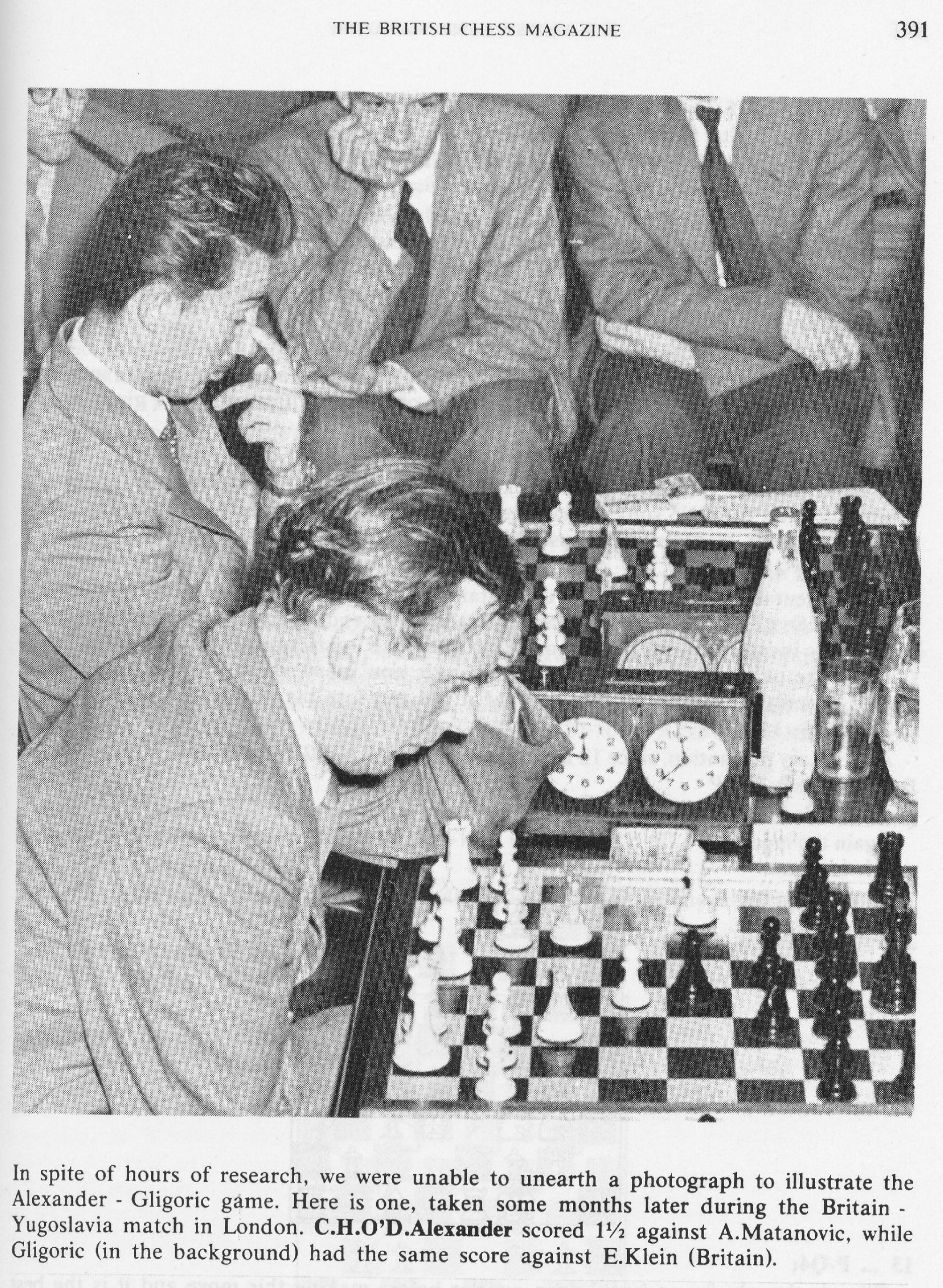

From The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match by E.Klein and W.Winter :

“CHO’D Alexander was born in Cork in 1909 and learned chess at the age of ten. He was educated at King Edward School, Birmingham, where he exhibited early prowess by winning the Birmingham Post Cup. In 1927 he won the British Boy’s Championship. During his student days, from 1928 to 1932, he was a convincing champion of Cambridge University. Subsequently he competed in five British Championships, winning the title in 1938. He also played in several international tournaments, his outstanding performance amongst these being Hastings in 1938, where he shared second and third prizes with Keres, following Reshevsky who won the tournament, and ahead of Fine and Flohr. In 1939, in the England-Holland match, he had the satisfaction of defeating the ex-World Champion, Dr. Euwe, in a sensational games, drawing the return game.

A brilliant mathematician, he took a first at Cambridge and chose a scholastic career, joining a well-known public school (Winchester College). From there, via a short spell in a business appointment (John Lewis), he entered the service of the Foreign Office, where, during the war years, his valuable work earned him the OBE.

He plays imaginative and courageous chess and is never afraid of the wildest complications.”

From British Chess Magazine, Volume XCIV (94, 1974), Number 6 (June), pp. 202-204 by PS Milner-Barry :

With the death of Hugh Alexander at the age of 64, British chess has lost the outstanding figure of the past forty years. His active playing career over some thirty years included two victories in the British championship and regular appearances in all representative teams from l93l-58, except when the nature of his Civil Service

duties prevented him from travelling behind the Iron Curtain. During the whole of the period after the war he was the regular top board for the England team. In the Hastings international congress he twice won the Premier tournament, on the second occasion tying with Bronstein. His victories in this series included two world champions (Euwe and Botvinnik) and numerous others in the Grandmaster class. He was an outstanding example, like H.E.Atkins and Dr. Milan Vidmar, of the amateur who could combine an exacting professional life of great responsibility and distinction with success in competitive international chess at the highest level and with the increasing professionalism of the game and the demands of knowledge and research that it makes upon the masters, this was much more difficult in Hugh’s time than in an earlier age.

It was indeed in the international field that his fame will principally rest. On the British championship scene, although he always did well before the War, and won convincingly at Brighton in 1938 in a strong field, his record did not match his abilities. He never established anything like the superiority over his contemporaries that Atkins in a former age and Penrose in a later achieved. He won the championship again, in 1956, but that was a weak year when the Moscow Olympiad took first claim on the leading British players. It was not that he cared less – like all the great players he hated losing, though he was the most magnanimous of opponents – but that he seemed to require the stimulus of the great occasion, and of a world famous name on the other side of the board, to bring out the best in him.

Alexander was perhaps the only English player of his day whom the Grandmasters would have treated as on a level with themselves. On his day he was liable to beat any of them, and they were well aware of it. In his younger days he was very much the gay cavalier, and a brilliant combinative and attacking player with a touch of genius. Latterly he lost some of this elan, and adapted his style to the responsibilities of the B.C.T. top board. His opponents too, with a healthy respect for his powers, were less inclined to give him opportunities. He was as capable of the dead-bat technique as anybody, and to that extent (to my way of thinking anyway) his games became less interesting, with quick draws making a higher contribution to his top-board results than in earlier years. But none the less he was the anchor-man of the British team until his retirement after the 1958 Olympiad.

It was a great pity he gave up the game over the board at 50. He had years of good chess in him. But I think he felt he had scaled all the peaks he could scale, and that he was finding top-class competitive chess a burden difficult to reconcile with his Civil Service work and the prospect of a gradual and inevitable decline in his powers did not appeal to him. I made many efforts to tempt him back to the arena, but to no avail. I do not think he ever seriously regretted his decision, and in his last years he immensely enjoyed correspondence chess.

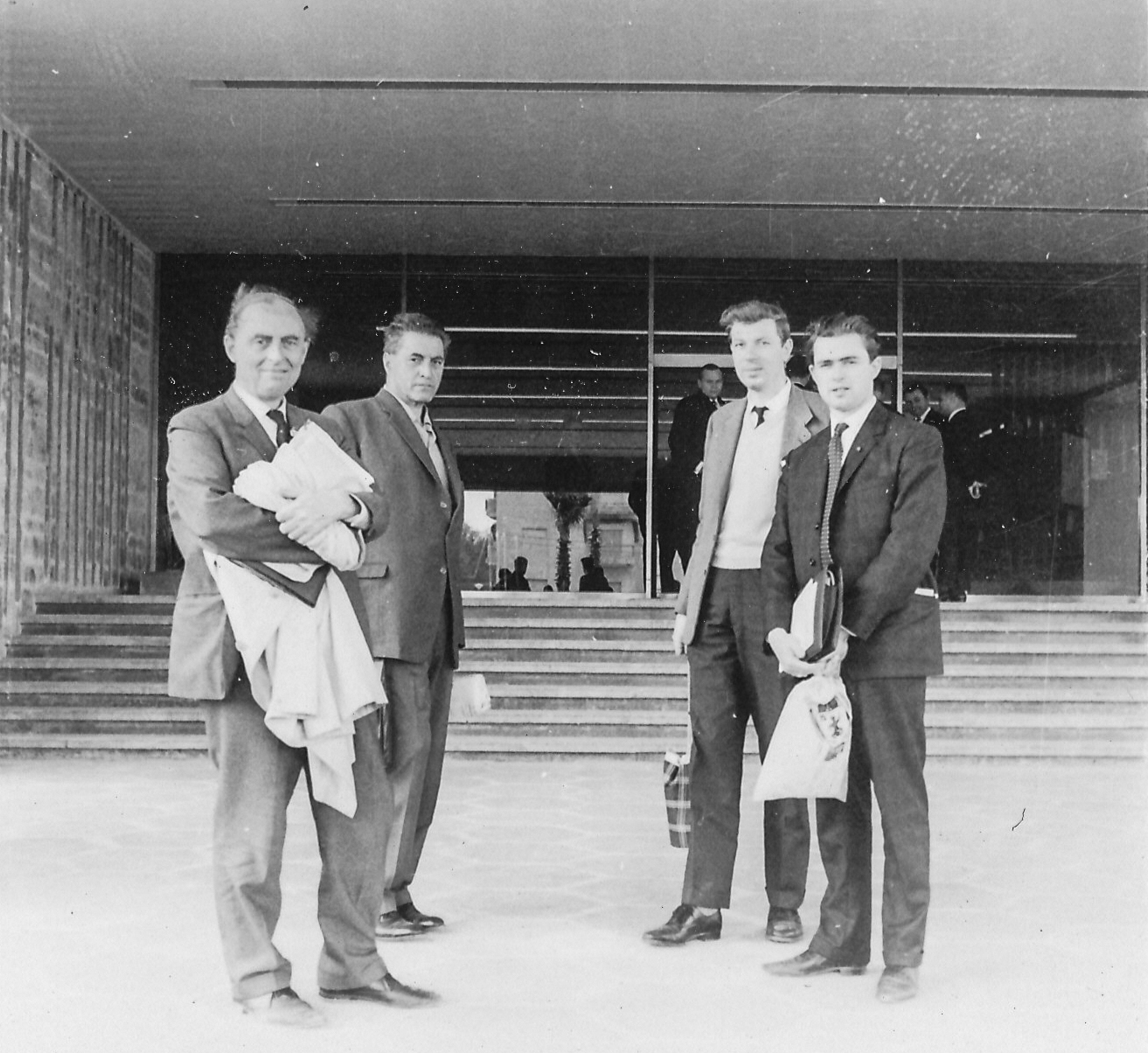

In 1964, Alexander became non-playing captain of the B.C.F. team, and held that role continuously until after the Siegen Olympiad in 1970.

It was rather a disappointing period for British chess, and the results, while we were rebuilding a young team, could not – even with Penrose’s outstanding efforts at top board – have been expected to be favourable. But he threw himself wholeheartedly into all the work sponsored by the B.C.F. and the Friends of Chess to find and develop talent in the younger generation, and before he died the fruits of these labours were beginning to appear. He would have been proud indeed to have witnessed our recent triumph in the Anglo-German match.

As a captain he was, of course, immensely liked and respected by his team. My impression was that he took his responsibilities almost too seriously, and agonised too

much over his decisions about whom to play and whom to rest. Nevertheless on balance he thoroughly enjoyed the work, and certainly, in spite of his innate modesty, he

was never one to be disturbed by ill-informed or irresponsible criticism, of which he had his share.

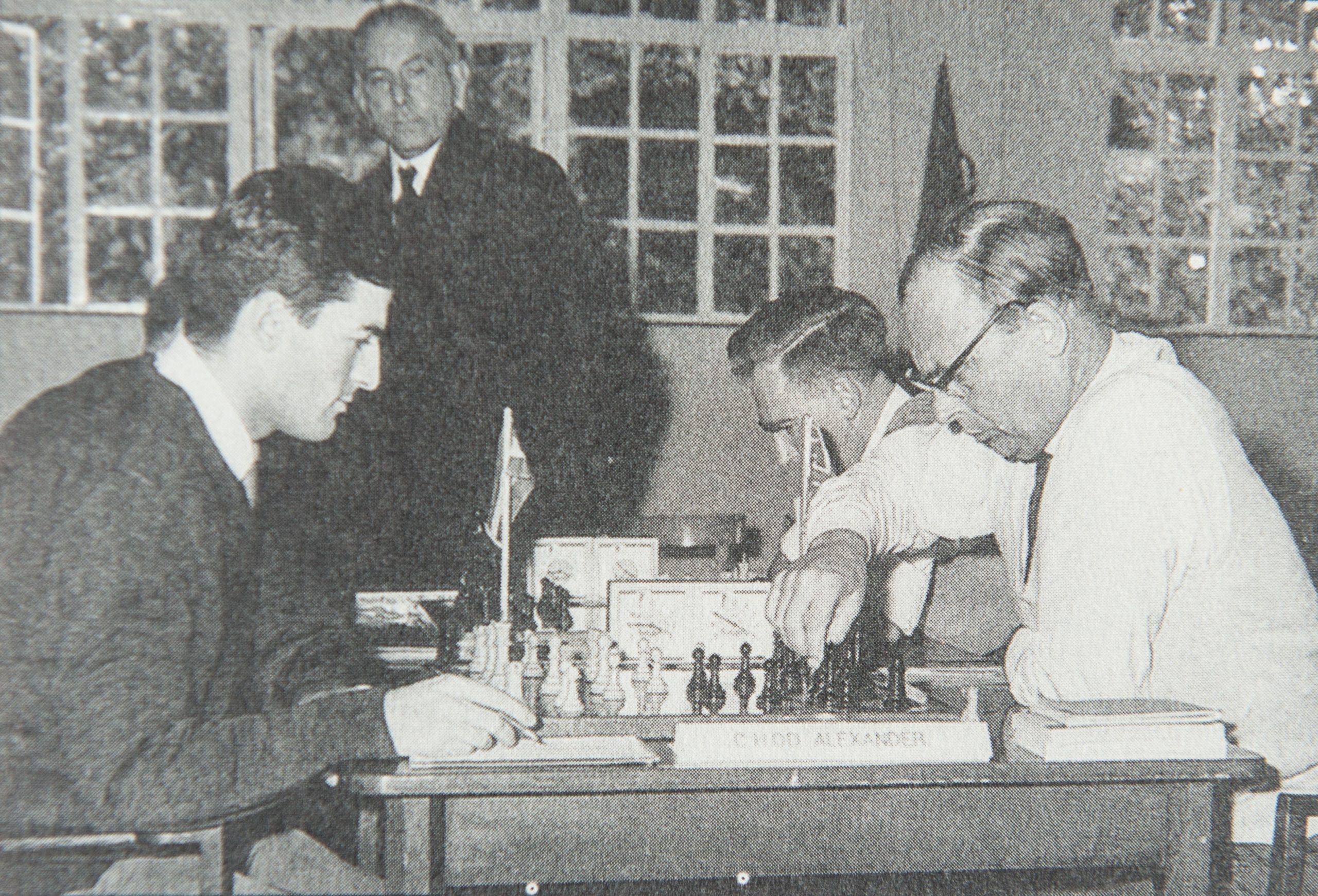

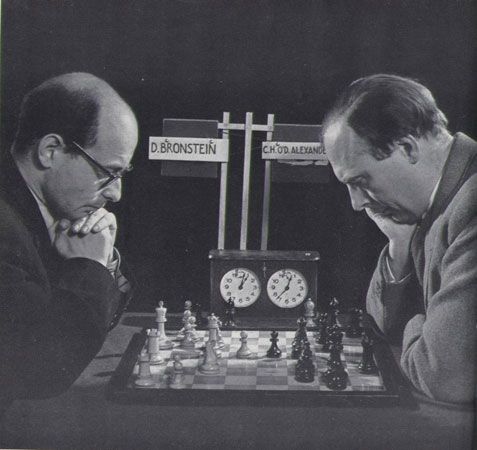

I suppose his most famous tournament result was his equal first with Bronstein at the Hastings Christmas Congress of 1953. Coming at a time when we were gloomily resigned to British players bringing up the rear in international tournaments, this created a great sensation.

The game with Bronstein lasted over 100 moves and Alexander won a most difficult Queen and Pawn ending by impeccable technique.

He went on with the Black pieces to massacre Tolush, the other visiting Russian Grandmaster.

Immense interest was created by this event. The popular press carried diagrams of the successive phases of the Bronstein saga. It was reported on the radio. By comparison with the furore created by the Spassky/Fischer match, it was no doubt small beer, but for those days the publicity was tremendous, and Alexander became the

hero of the hour.

It was entirely characteristic of him that this adulation did not go to his head. He kept everything in proportion, and encouraged everybody else to do the same. He said all the right things about Bronstein, but he did not claim, as one tends to do on these emotional occasions, that international sport was a panacea for friendship between the nations. Altogether it seemed to me an impeccable performance both on and off the board.

It is as a player that Hugh would, I think, have best wished to be remembered; and I have left myself little room to say anything about him as a journalist and writer. We are blessed, as readers of the B.C.M. will know, with many good and interesting writers on the game. But Hugh had, I believe, exceptional talents as a journalist. In his columns in the ‘Sunday Times‘, and latterly the ‘Financial Times‘, he set a very high standard. He always had something fresh and original to say, especially, I think, to the intelligent amateur rather than the expert; and he said it in a way that was both disarmingly modest and yet lively and entertaining. The warmth of his personality came out clearly both in his writing and in his public speaking – both were entirely natural and wholly without amour-propre.

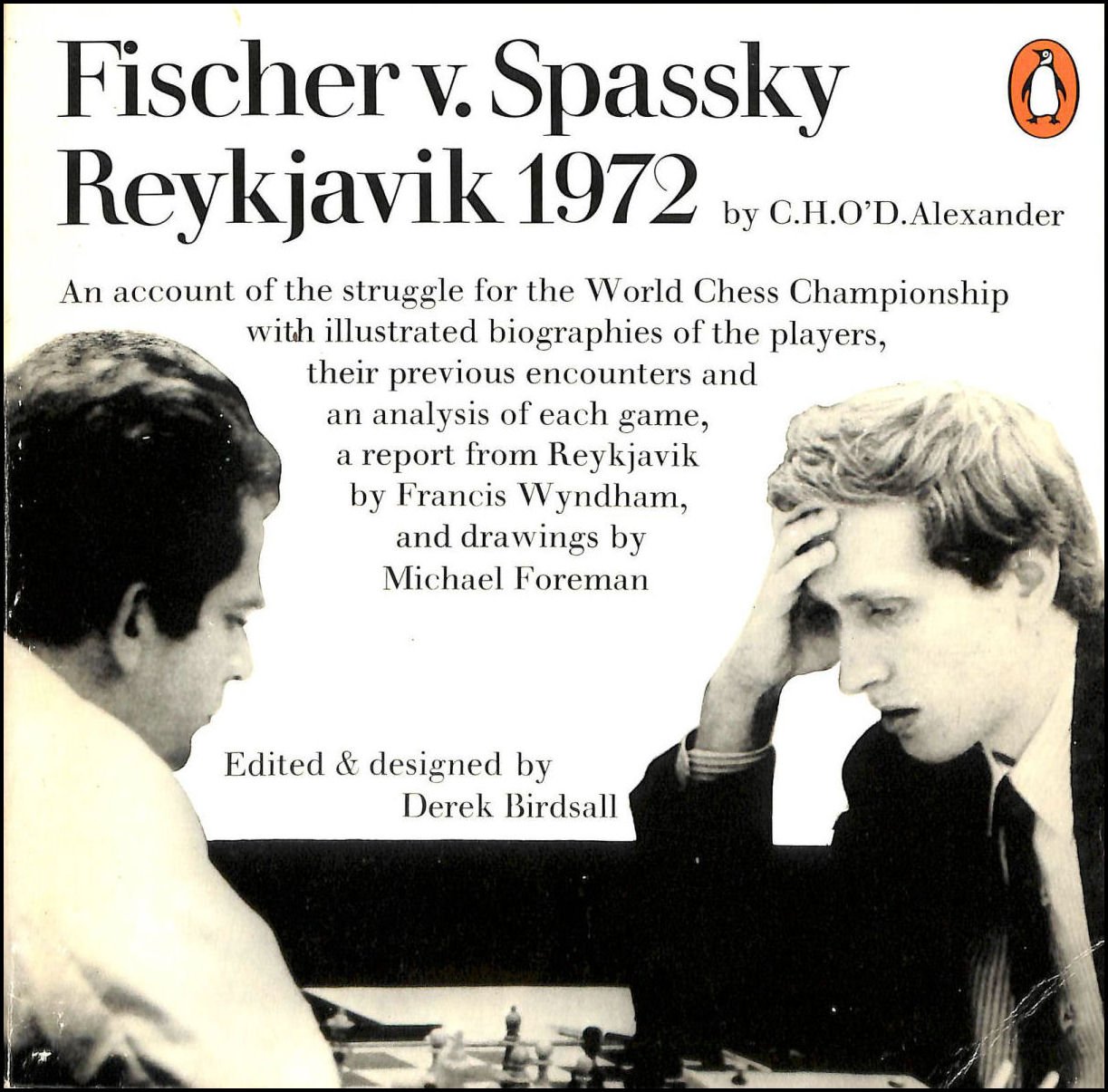

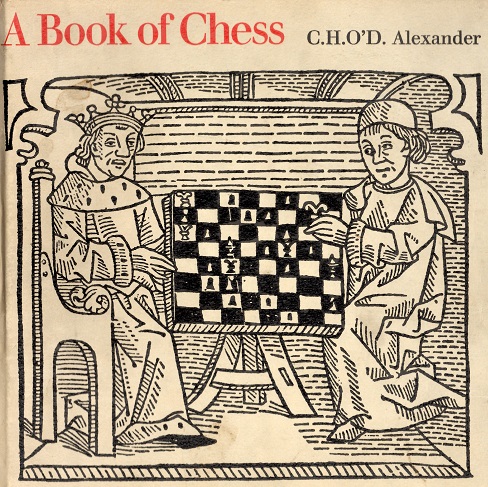

His articles gave great pleasure to a wide circle, and many who never met him in the flesh must have felt that they had come to know him as a person. Similarly his book on the Spassky-Fischer match

(like the ‘Book of Chess’, which was written in the last year of his life) is an extremely vivid, as well as scholarly, piece of writing. It is almost impossible to believe that it was completed, within days of the conclusion of the match, by a man apparently under sentence of death throughout its progress.

Now that it has come, the loss of Hugh Alexander to British chess and chessplayers, alike as player, writer, administrator and friend, is immeasurable.

From CHESS, Volume 39 (1974), Nos. 693-94, March, p.162 by BH Wood :

The death of Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander deprived English chess of one of its most vivid characters. Born l9th April 1909, he learnt chess at the age of 8.

From a Londonderry college he went to King Edward’s School, Birmingham, where as a schoolboy he won the Birmingham Post cup, which carries with it the unofficial championship of Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire. Going on to Cambridge, he not only won the University championship four years in succession, but picked up first-class honours. He won the British championship in 1938.

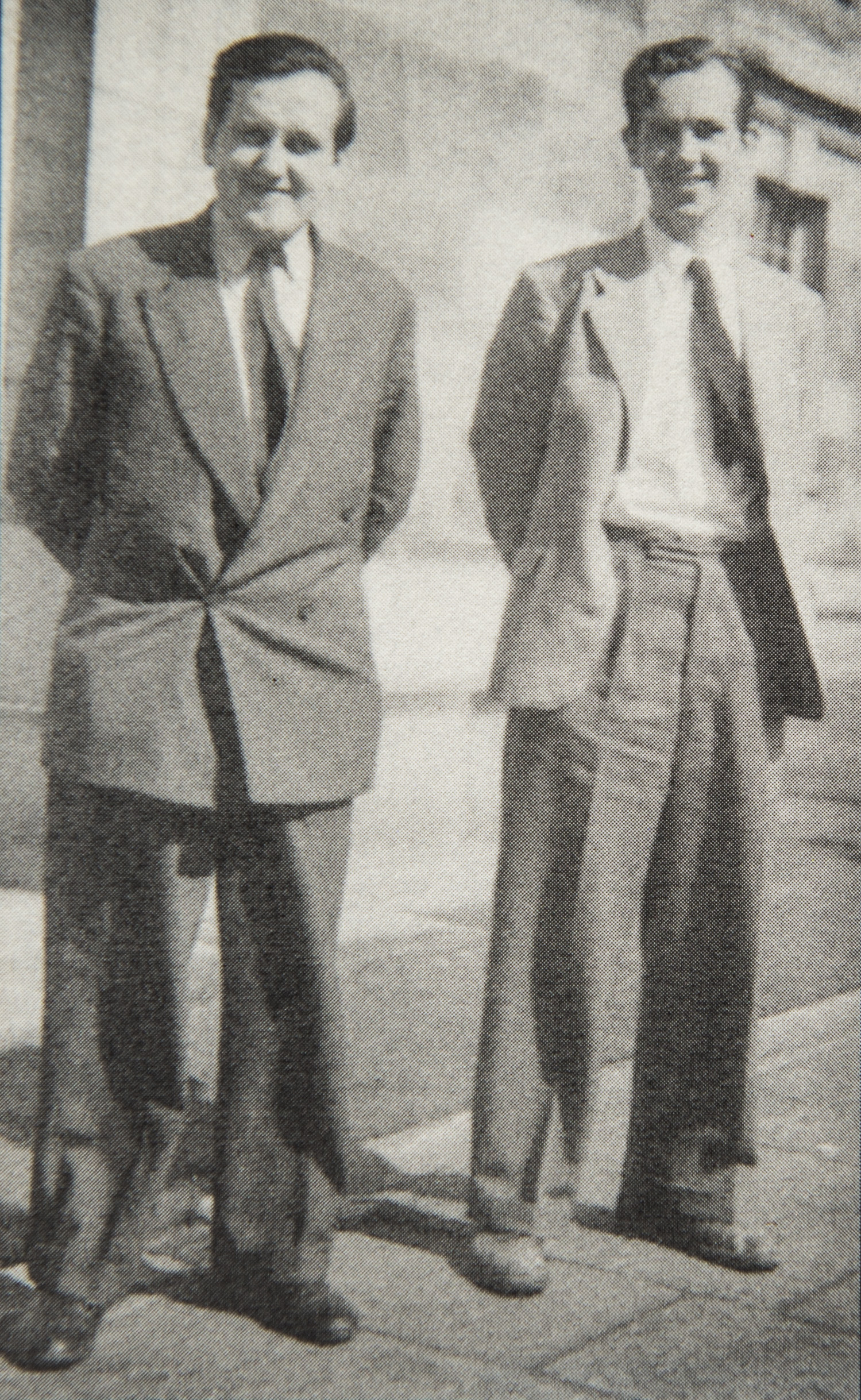

In 1939 I found myself on a boat with him bound for the Chess Olympiad in Buenos

Aires. He was team captain with Sir George Thomas, P. S. Milner-Barry and H. Golombek

other distinguished members of the team.

War broke out after about six rounds. With typical determination, Alexander jettisoned chess for patriotism, caught a boat home, volunteered for service on disembarking, and within a few weeks had attained the rank of colonel in British Intelligence. He remained attached to Intelligence and the Foreign Office until his

retirement a few months ago. As a curious consequence of this commitment, though he settled in to the team captaincy for the British Chess Federation in the biennial chess Olympiads and participated in many chess events abroad, he was never allowed to travel anywhere behind the iron Curtain.

His fame certainly did, however. In the radio match, Britain v USSR in 1946, the most important event in British chess for a decade before and after, he found himself pitted against Mikhail Botvinnik, then at the height of his powers and destined to hold the world championship for 14 years. The first game he lost; the second he won, in superb style. His great adversary was outplayed.

He had some great years at Hastings. A 120 move victory over Bronstein with a queen and pawns endgame stretching over l3 hours through 3 days, earned headlines in the national press unequalled until the Spassky-Fischer furore of 1972, won him first place in 1954 and started him with a chess column in the Sunday Times. He was equal with Bronstein, above O’Kelly, Matanovic, Olafsson, Teschner, Tolush, Tartakover, Wade and Horne.

Hastings illustrated Alexander’s weaknesses as well as his strengths. Twice he won the premier tournament there, only to finish among the tail-enders the year after. Only once more was he to win the British champ- ionship; in a rather weak field, entering at the last minute with typical opportunism.

He was a brilliant conversationalist and speaker, a fine bridge player, a master mathematician, an expert on codes, a first-class journalist and writer. Among varied other interests were croquet and philately. He threw himself wholeheartedly into anything he did. His organization, “The Friends of Chess”, provided generous financial support for a wide range of chess events. A few days before his death he was full of plans for the future, including a big History of British Chess. He burnt himself out. The world of chess is a poorer and duller place without him.”

From Chessgames.com :

“Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander was born in Cork, Ireland. Awarded the IM title in 1950 at its inception and the IMC title in 1970, he was British Champion in 1938 and 1956.

During the Second World War, he worked at Bletchley Park with Harry Golombek and Sir Philip Stuart Milner-Barry, deciphering German Enigma codes and later for the Foreign Office. Alexander finished 2nd= at Hastings (1937/38) tied with Paul Keres after Samuel Reshevsky and ahead of Salomon Flohr and Reuben Fine. He held Mikhail Botvinnik to an equal score (+1, -1) in the 1946 Anglo-Soviet Radio Match, and won Hastings (1946/47) while finishing equal first at Hastings (1953/54). He represented England on six Olympiad teams. Alexander was also an author of note. He passed away in Cheltenham in 1974.”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

International Master (1950), International Correspondence Chess Master (1970). Born in Cork, he settled in England as a boy. In spite or because of his intense application at the board his tournament performances were erratic. From about 1937 to the mid 1950s he was regarded as the strongest player in Great Britain, although he won only two (1938, 1956) of the 13 British Chess Federation Championships in which he competed; he played for the BCF in six Olympiads from 1933 to 1958. Holding a senior post at the Foreign Office, he was not permitted to play in countries under Soviet control or influence; but when he did compete abroad he achieved only moderate results. His best tournament achievement was at Hastings 1937-8 when he was second (+4=5) equal with Keres after Reshevsky ahead of Fine and Flohr; but he is better remembered for his tie with Bronstein for first prize at Hastings 1953-4. He won his game against Bronstein in 120 moves after several adjournments, and the outcome became a kind of serial in the press, arousing great national interest in the game. Alexander was the author of several books on chess, notably Alekhine’s Best Games of Chess 1938-1945 (1949) and A Book of Chess (1973).

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks :

For many years the chess correspondent of The Sunday Times, The Spectator (pseudonym Philidor) and the Evening News. There was probably no “chess name that was better known to the non-chess-playing element of the British public than that of Hugh Alexander. His victory over Russian Grandmaster David Bronstein at Hastings in 1953, after a struggle which lasted for 120 moves and took 13 hours, made chess front page news in the British press.

Born in Cork on 19th April 1909, Alexander picked up the game at prep school at the age of 8. In 1926 he won the Boy’s Championship, later to be recognised as the British Boy’s Championship, at Hastings. After coming down from Cambridge University, where he won the university championship four times, Alexander taught mathematics at Winchester College from 1932 to 1938. He later joined the Foreign Office.

One of the few British players who might have reached World Championship class if he had chosen to devote sufficient time to the game, Alexander was at his best when he faced a top class opponent.

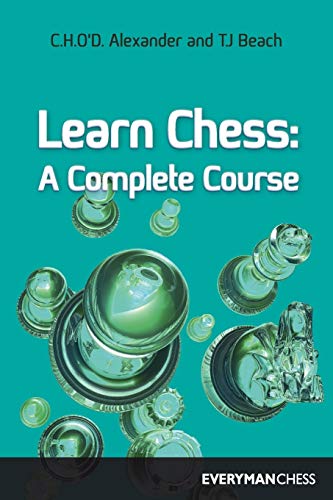

During his chess career, he scored victories over two World Champions Botvinnik and Euwe, and he beat a number of other Grandmasters, international tournaments were all at Hastings where he came =2nd in 1938 with Keres, half a point behind Reshevsky and ahead of Fine and Flohr; 1st in 1947 and =1st with Bronstein in 1953. In 1951 tournament he came =5th.His other hobbies included bridge, croquet and philately, He was the Author of Alekhine’s Best Games of Chess 1938-1945 (Bell), Chess (Pitman) and joint author with T.J. Beach of Learn Chess; A New Way for All (Pergamon Press);

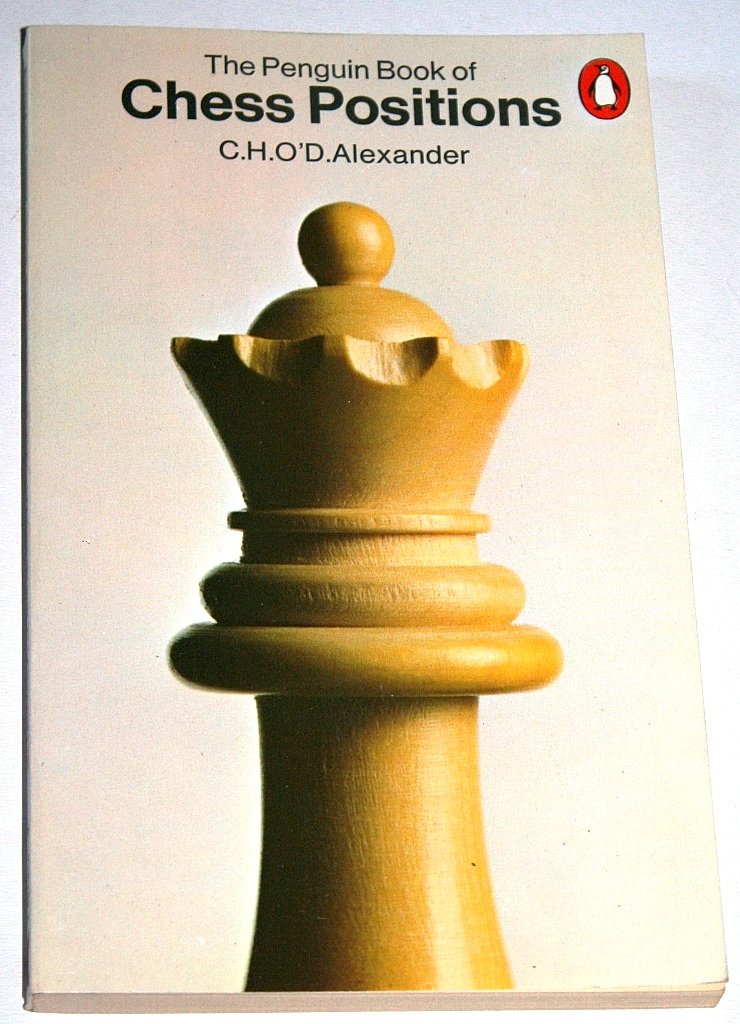

A Book of Chess (Hutchinson) 1973; The Penguin Book of Chess Positions (Penguin) 1973.

Here is an interesting article on his film appearance.

Here is his detailed Wikipedia entry

According to C.N. 10817 Hugh lived at various addresses when working at GCHQ :

- Brecken Lane, Cheltenham.

- 28 King’s Road, Cheltenham, GL52 6BG.

- Old Bath Lodge, Thirlestaine Road, Cheltenham, GL53 7AS.

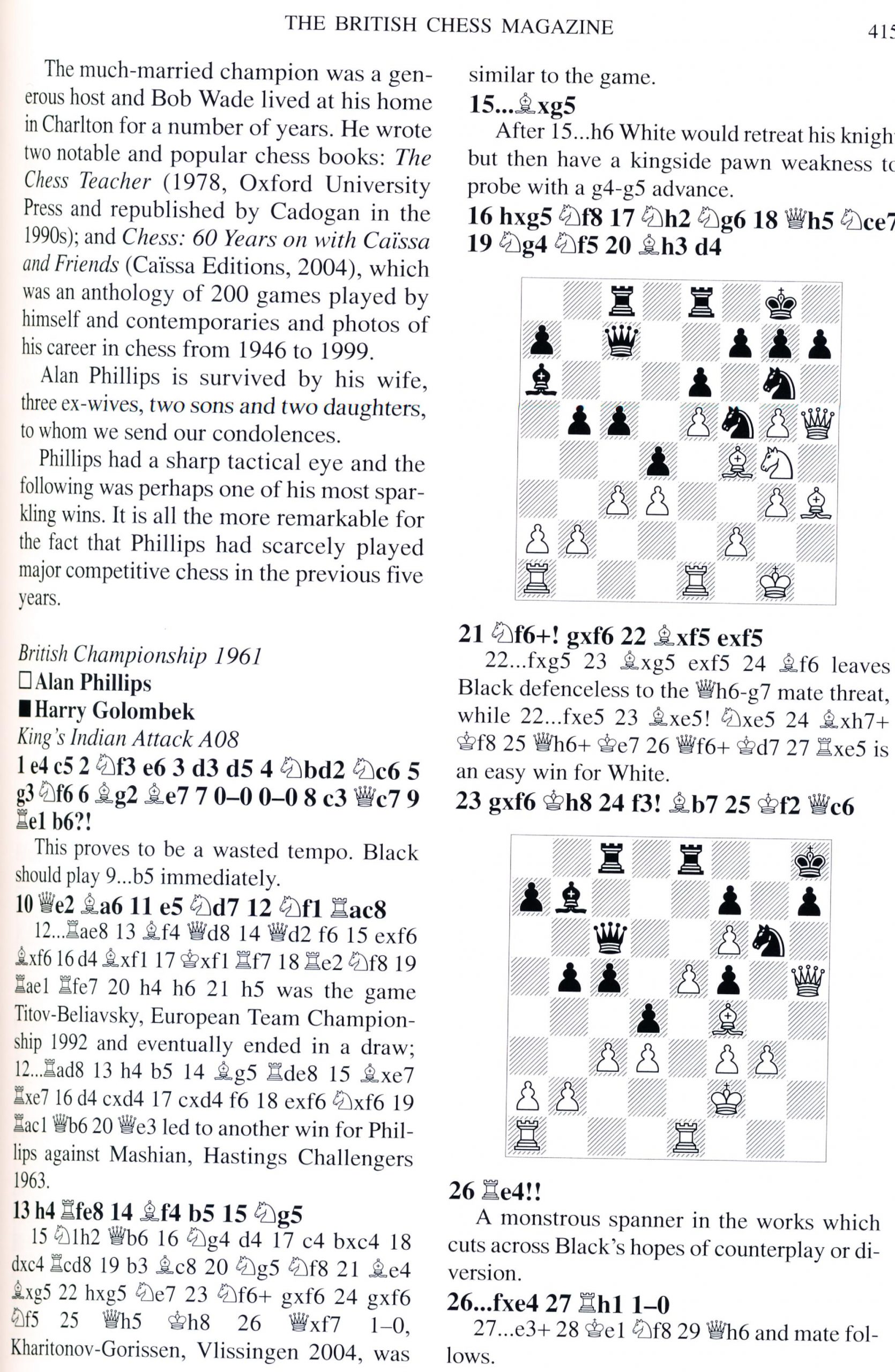

Golombek and Hartston, The Best Games of C.H.O’D. Alexander (1976).