Between 31 August and 9 November 1888, five prostitutes were brutally murdered in Whitechapel, in London’s East End. Their killer was never caught, and is known to us now as Jack the Ripper. Several later murders in the same area might have been committed by the same person.

What you all want to know is this: did Jack the Ripper play chess?

Hundreds of possible suspects have been mentioned over the years: almost everyone, it seems, who was in the right place at the right time, and even some who almost certainly weren’t.

Several of these suspects have chess connections.

First on our list is the artist Walter Sickert. From The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict: ‘According to a well-argued book by Stephen Knight, Jack the Ripper … was in fact the painter Walter Sickert as part of a three-man team. One of the things we know about Sickert was that he was a keen chess-player’.

Sadly, this source is notoriously unreliable. I searched the newspaper archives for any connection between Sickert and chess. All I could find was a critic’s view of a portrait of political activist and atheist Charles Bradlaugh: ‘But the clever artist should have placed a chessboard on the table over which the intellectual face of Mr. B. is bending. He habitually plays chess, I am given to understand, with members of the high aristocracy, and recently checkmated a Bishop.’ This must surely refer to Bradlaugh, who was known to be a chess player, rather than Sickert, although history doesn’t record whether the famous atheist used a bishop to checkmate the Bishop. Perhaps Mike Fox had read a biography of Sickert which provided more information, but I can find no evidence of the artist being particularly interested in chess.

More recently, the crime novelist Patricia Cornwell took up the theory of Sickert being Jack, but I don’t think the evidence stands up.

Number two on our list is none other than Lewis Carroll. We know, of course, that he was a chess enthusiast: you can read more here. I’ve known the compiler of this information, Roger Scowen, on and off for many years: we recently exchanged emails and hope to meet up soon for a few games once it’s safe to do so. But was Carroll Jack the Ripper? To me, it seems like a totally ridiculous suggestion.

Moving swiftly on, let’s visit the Langdon Down Museum of Learning Disability in Teddington – and if you’ve never been there you really ought to. Some of the inmates there at Normansfield were identified by John Langdon Down as having a specific genetic condition which is now known as Down Syndrome. Others, like James Henry Pullen, might now be diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum. Facilities were also available for members of wealthy families with mental health conditions, one of whom, who features, with a mention of his chess prowess, in a display in the museum, was Reginald Treherne Bassett Saunderson. Saunderson certainly didn’t have an intellectual disability, but today he’d probably be diagnosed as schizophrenic. His story is told here.

In this game he was winning most of the way through against a strong opponent, but eventually came off second best.

Saunderson was certainly a pretty good chess player, and certainly killed a lady of, reputedly, ‘ill-fame’, but, born in 1873, he was much too young to have been the original Jack the Ripper.

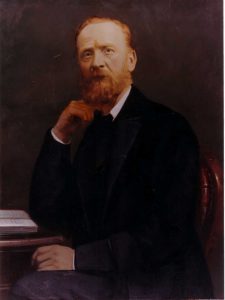

Let’s try again. Lord Randolph Churchill, Winston’s dad, was certainly a chess player, and certainly an opponent of Steinitz. By all accounts he was a pretty unpleasant and unpopular man, but, although he sometimes appears in lists of possible suspects, there’s absolutely no evidence that he had anything at all to do with the Whitechapel Murders.

Finally, meet S Swyer. He played Steinitz in the second round of a handicap tournament at the City of London Chess Club in 1871-72: among the other participants was J Swyer, a first round loser. Tim Harding (Steinitz in London) suggests that the two Swyers were probably brothers, but doesn’t provide any further information. Swyer is an uncommon surname so it’s not too difficult to find out more.

The Swyer family came from near Shaftesbury, in Dorset. Walter Swyer and Sarah Lush (Buckland) Swyer had a daughter, Sarah, followed by seven sons. Walter and Robert, John and George, James and William, and, as was the custom in educated families at the time, their seventh son was named Septimus. Let’s get J Swyer out of the way first. John was a bank manager who spent most of his life in Dorset. James was a chemist and druggist, living in Bethnal Green in London’s East End at the time of the 1871 census, so it must have been him, rather than John, who played chess at the City of London Chess Club.

S Swyer, then, was Septimus. In 1871 he was a General Practitioner, living in Brick Lane, Spitalfields, not very far from his brother Jim. As well as being a GP he specialised in obstetrics and gynaecology.

Both Swyers were placed in Class IV (of V) at the City of London Club, so when Steinitz was paired against Septimus he took the white pieces in both games, but had to play without his queen’s knight.

This game suggests that Septimus was a reasonably competent player, but handicapped by a lack of opening knowledge.

It was much the same story the second time around, but here the game was truncated when Swyer, in a difficult position, hung a rook.

Swyer was a colourful character whose life was not short on controversy. In 1861 a cat, allegedly belonging to his neighbour, broke into his shop and shattered all his medicines, including a bottle of Godfrey’s Cordial, but the narcotic had no effect on the feline intruder. He sued for damages, but his neighbour claimed it was a different moggy and the case was thrown out.

His first wife died in 1874 and he remarried in 1880. It was stated his second wife’s husband was still alive (it seems he lived until 1912) and she was tried for bigamy, but acquitted.

In 1888 he was still in the same area, but in 1891, shortly after the last possible Ripper murder, he suddenly emigrated to the USA. He certainly had financial problems, but who knows?

Dr Septimus Swyer was in the right place at the right time, had the required medical knowledge, and left the country in a hurry. Only circumstantial evidence. Was he Jack the Ripper? Unlikely, I would have thought, but at least, unlike our other four chess-playing (or perhaps not in the case of Sickert) suspects, a possibility. I guess we’ll never know.

Sources:

There’s a lot more about Swyer as a Ripper suspect (but do bear in mind the proviso at the top of the first post) at:

Dr Septimus Swyer + proviso – Casebook: Jack the Ripper Forums

A lot more again here from a direct descendant (one of his sons emigrated to Australia) at:

Septimus Swyer (hibeach.net)

Photographs of James and Septimus Swyers taken from family trees at:

Genealogy, Family Trees and Family History Records online – Ancestry®

Photograph of Lord Randolph Churchill from Wikipedia.