Then Ellis comes with rapid transit,

And few there are who can withstand it;

Some day soon he’s bound to land it.

So said the bard of Richmond Chess Club at their 1911 AGM. Arthur Compton Ellis was a man who lived his life, as well as playing his chess, with rapid transit. Although he spent little more than two years in the area, he flashed like a meteor across the Richmond and Kew chess scene.

Let’s find out more.

Our story starts on 20 September 1887, with the marriage between George Frederick Ellis, a surveyor aged 39 and Margaret Fraser, aged 31. Rather late for marriage in those days. Their only child, Arthur Compton Ellis’s birth was registered in the Pancras district of London in the first quarter of 1889.

In the 1891 census the family are living in Kentish Town. George is working as a Surveyor of Roads and Sewers, and they’re doing well enough to employ a servant. By 1901 they’ve moved a mile to the north, close to Parliament Hill Fields: George is now, just like James Richmond Cartledge would be a few years later, a Deputy Borough Engineer and Surveyor. Margaret is, perhaps unexpectedly, working as a Physician and Surgeon, while Arthur is at school. There were no domestic staff at home.

Arthur moved from school to the University of London, where he graduated with a BA in 1909, at the age of only 20. In the same year his father died: the death was registered in Camberwell, South London.

Perhaps he discovered the game of chess at university. He may also have discovered religion. In 1908 he was baptised at St Luke’s Church, Kew, with his address given as 40 West Park Road, right by Kew Gardens Station. At this point the family appeared to have connections, then, with both the Richmond/Kew area and South London.

He first turns up playing for Richmond Chess Club in December 1908, losing his game on bottom board in a London League match against Ibis. It looks like he joined the club on the completion of his studies. Although he seemed to be struggling in match play at this point, in April 1909 he finished second in a lightning tournament, which, that year, replaced the annual club dinner.

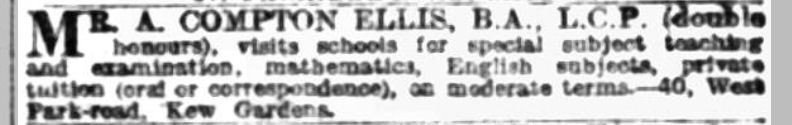

In 1910, now styling himself A Compton Ellis, he was advertising his tuition services in the Daily Telegraph. LCP was a teaching qualification.

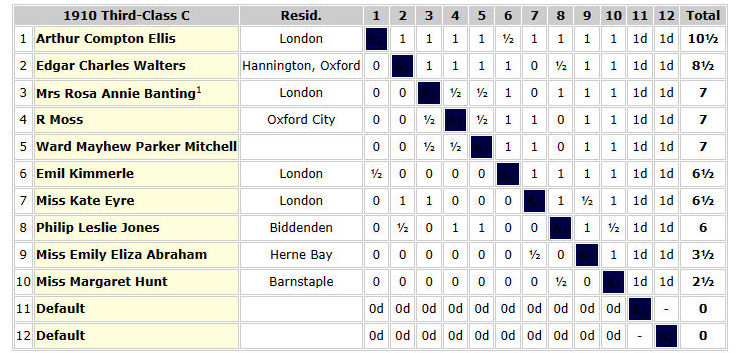

By Summer 1910 he felt confident enough to take part in a tournament. The British Championships took place that year in Oxford, and Arthur was placed in the 3rd Class C section. With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than William Archibald Spooner.

With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than William Archibald Spooner.

A handicap tournament also took place there, in which he won first prize: a model of the earth with a clock inside, enabling him to ascertain the time of day in any part of the world. This prize was donated by its inventor, James Haddon Overton, a schoolmaster from Woodstock.

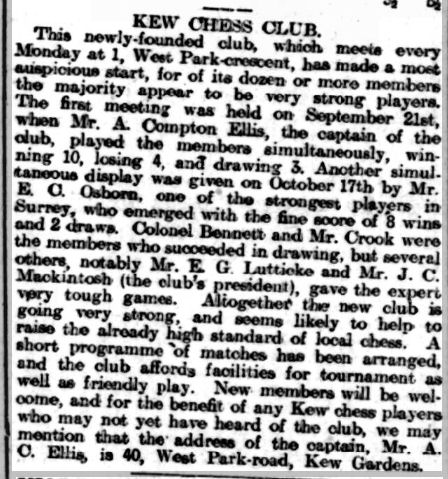

In September that year, not content with only playing at Richmond, where he had now reached top board in a match against Acton, he was one of the founders of a new club in Kew.

Richmond and Kew weren’t his only clubs, either. He was also a member of South London Chess Club, about which there’s very little information online.

In this London League game he fell victim to a brilliant queen sacrifice. Click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up window enabling you to play through the game.

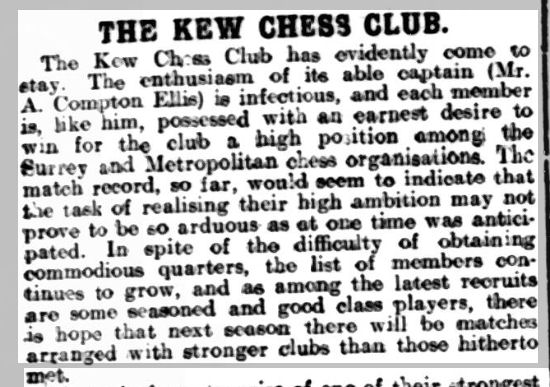

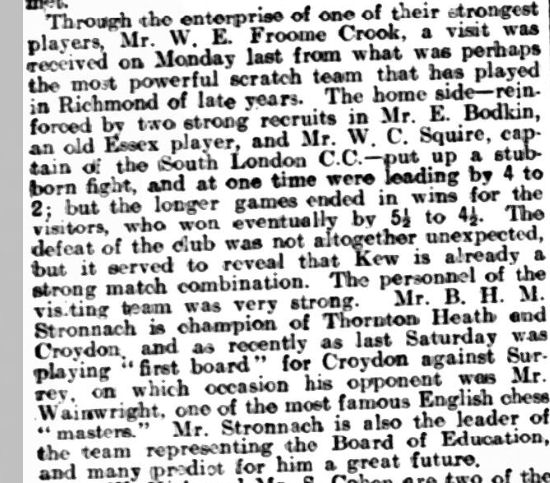

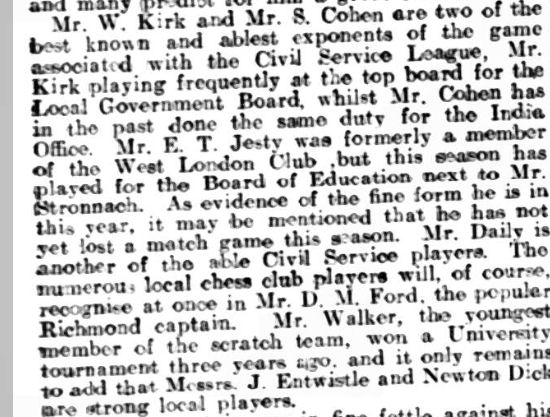

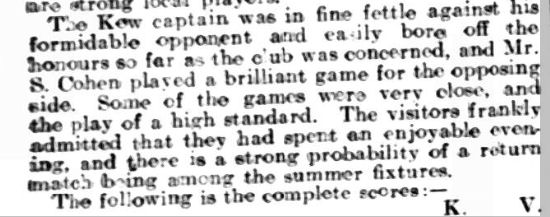

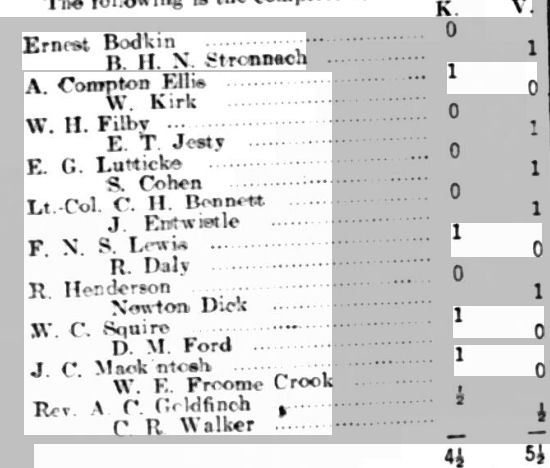

Arthur Compton Ellis was infectiously enthusiastic, ambitious and seemed to have contacts with a number of strong amateur players, mostly from the Civil Service, as is demonstrated by this event.

A win against our old friend Wilfred Hugh Miller Kirk was also evidence that Arthur was developing into a formidable player.

The 1911 census found Arthur and his mother still living at 40 West Park Road, Kew Gardens. Arthur gave his occupation as ‘Tutor’ while there was no occupation listed for Margaret.

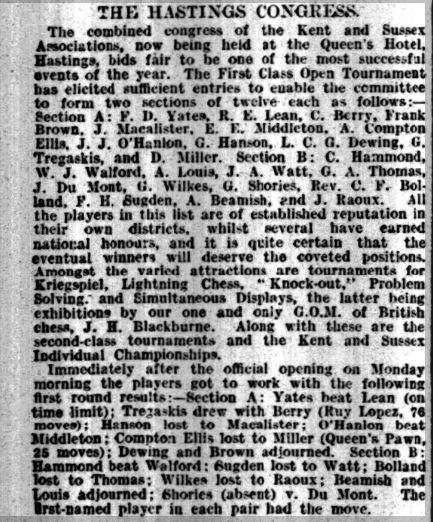

By then it was time for another tournament. The Kent and Sussex Chess Congress, run by the Kent County Chess Association took place over Easter at this time. It’s little written about today, but it attracted some of the country’s top players. The top section in the 1911, for example, played in Tunbridge Wells, was won by Yates ahead of Gunsberg. The organising committee, coincidentally, included the Kent secretary Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson, and the Sussex secretary, Harold John Francis Spink Stephenson. Arthur Compton Ellis took part in the third section down, the Second Class Open, where he was again too good for the opposition, finishing on 8½/10, half a point ahead of Battersea veteran Bernard William Fisher (1836-1914), who had been a master standard player back in the 1880s. Visitors included Frank Marshall, who gave a simul and a talk, and Joseph Blackburne, who gave simuls and played consultation games. Horace Fabian Cheshire gave a talk, with lantern slides, on chess players past and present, and also an exposition of the game of Go. It sounds like a good time was had by all.

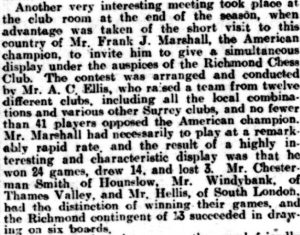

Arthur persuaded Frank Marshall to visit Richmond and give a simul against members of local chess clubs, and that was duly arranged.

The AGM in September would report as follows:

Always eager to play in any event, he won the Dalgarno-Robinson chess trophy, competed for by members of local branches of the Association of Young Men’s Clubs, and played on top board when Richmond Chess Club visited Hastings, drawing his game against the aforementioned Mr Stephenson.

He decided to give the 1911 British Championship, held in Glasgow, a miss, though. Perhaps he wasn’t prepared to travel that far.

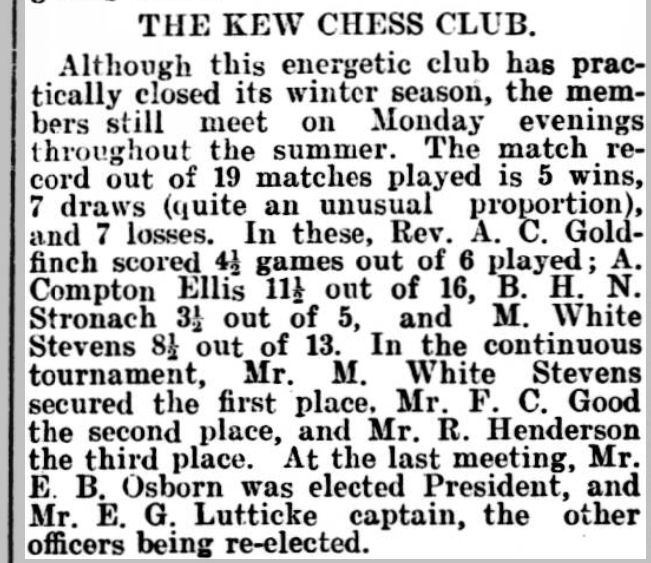

The Richmond Herald was now carrying less chess news, but we know from a report from the other end of Surrey that Kew Chess Club were becoming even more successful.

You’ll see that Ellis didn’t stand for re-election as captain. This seems to have been because Arthur and Margaret had moved from Kew to South London.

Over Easter 1912, though, he returned to Tunbridge Wells for the Kent and Sussex Easter Congress, this time promoted to the top (First Class Open) section. Now against stronger opposition, this time he found the going tough, only scoring 2½/8.

The winner was the future Sir George Thomas, who wasted little time of disposing of Ellis, who misplaced his queen’s knight on his 11th move.

However, he did have the satisfaction of defeating Fred Brown, one of two chess playing brothers from Dudley. (He had a brother Frank, who was also a strong player. Understandably, in the days when newspapers only gave players’ initials, they were often confused.) Fred shared second place with future BCM editor Julius du Mont in this tournament.

It seems that he was lucky here: his opponent resigned what may well have been a drawn position as he would have had chances of a perpetual check if he’d continued with 32… Kf7!. What do you think?

At the same event, Arthur and his friend from Kew, Montague White Stephens, played in a consultation simul against Blackburne. They were successful after the great veteran uncharacteristically missed a simple mate in 3 on move 19.

Montague White Stevens (1881-1947) was only a club standard player, but he edited the 1914 Year Book of Chess and produced a revised edition of EA Greig’s Pitfalls on the Chess-Board.

In April 1912 a new Chess Divan opened in the Strand, replacing Simpson’s Chess Divan, which had closed a few years earlier, and Gunsberg was appointed its manager. Arthur, who would go almost anywhere for a game of chess, was soon involved. With lightning tournaments a regular feature, a devotee of rapid transit chess would be in his element.

In May’s lightning tournament there was a full house, with the participants ‘mostly first-class amateurs’. Arthur shared first place with future British Champion Roland Henry Vaughan Scott and future writer and historian Philip Walsingham Sergeant. Lightning chess was proving increasingly popular, and I would assume this tournament was played using a buzzer. But there was an announcement that the following week there would be a five-minute tournament ‘which affords such amusing play’. If you think five-minute chess is amusing, you should try bullet. Arthur would have loved that.

In June there were only 12 players in the lightning tournament, with Arthur Compton Ellis sharing first place with Harold Godfrey Cole, who had played in the previous year’s Anglo-American cable match and would, a couple of months later, take second place in the British Championship. It’s evident from these results that he was a formidable speed player.

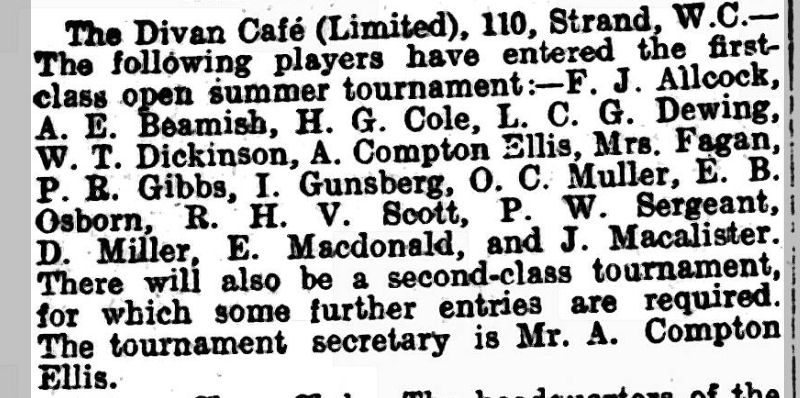

He was, inevitably, involved in administration as well.

A strong and interesting line-up, you’ll agree, with players such as former World Championship candidate Isidor Gunsberg and top lady player Louisa Matilda Fagan amongst many well-known participants.

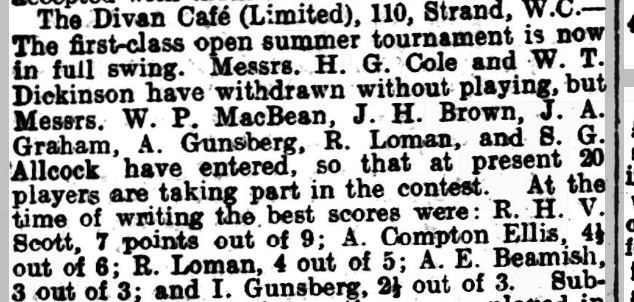

This wasn’t a standard all-play-all tournament: rather you could play as many games as you wanted against as many opponents as you wanted, with the player with the best percentage score of those who played at least 20 games winning. It sounds like you could improve your chances by playing lots of games against weaker players. On 22 June the London Evening Standard reported that Ellis had beaten Mrs Fagan and drawn with Scott.

There was further news in three weeks time, when some players had made a lot of progress with their games.

In this game against Scotsman John Macalister, a shorthand writer in the Admirality Court, he was winning but went wrong on move 19 in a complex position, eventually falling victim to a queen sacrifice.

By the end of August, Loman and Scott were both on 13/16, with 18 games now required for your score to count, but after that the trail goes dead. It looks to me like the whole concept was rather too ambitious to succeed.

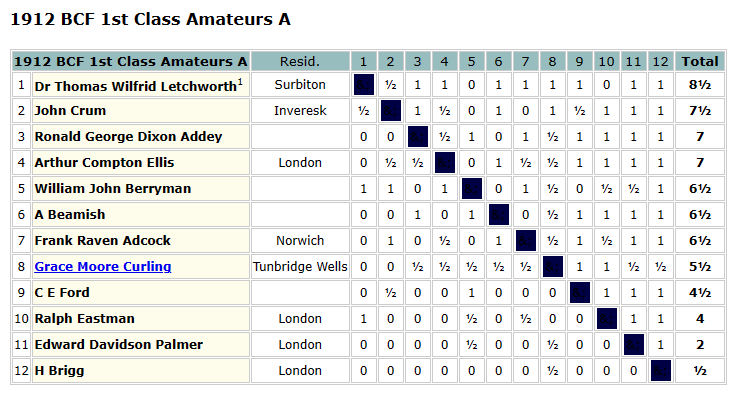

But meanwhile, the 1912 British Championships had taken place in Richmond, familiar territory for Arthur Compton Ellis. This time he was placed in the 1st Class Amateurs A section.

He made a strong showing with 7/11, sharing 3rd place behind Surbiton ophthalmic surgeon Thomas Wilfrid Letchworth (Wilfred Kirk won the parallel 1st Class Amateurs B section), but at this point he seemed to be a stronger lightning player.

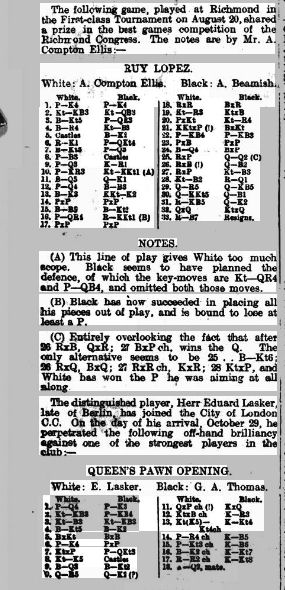

This game shared the prize for the best game played in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd class sections, judged by Thomas Francis Lawrence. The winning move seems pretty obvious to me, though. There is some doubt as to the exact identity of his opponent: three possibilities were put forward in a recent online debate, and you could perhaps add a fourth. I’ll discuss this further in a future Minor Piece.

He later provided brief annotations for the press, where it appeared immediately above a Very Famous Miniature which had been played a few days earlier. I’m sure you’ll recognise it.

This thrilling game against music professor Edward Davidson Palmer (he taught singing), in which Arthur ventured the King’s Gambit, is a good demonstration of his fondness for tactical play. His opening failed to convince and Palmer missed several wins, but he ultimately escaped with the full point.

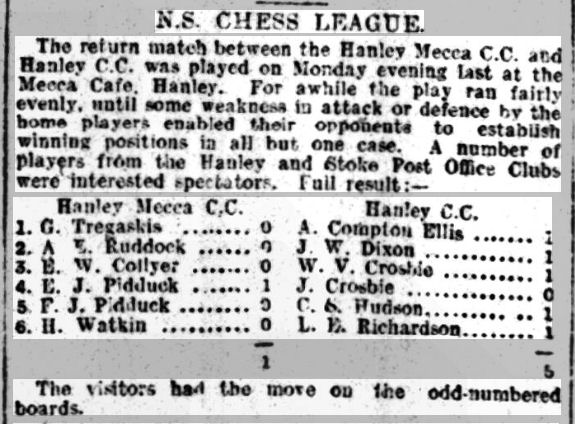

Over the next few months there’s little news of his chess playing, but then something unexpected happens. He turns up in, of all places, Stoke on Trent, or, to be precise, nearby Hanley.

Why Stoke on Trent? What was he doing there?

There are two possibilities. On Board 2 for Hanley was schoolmaster Joshua Walter Dixon, whom he had met in Oxford back in 1910: they were in different sections of the main event, but both competed in the handicap tournament. Perhaps he had been in touch to offer him employment there, either in a school or as a private tutor.

But look also at Arthur’s opponent from Mecca: George Tregaskis. It appears that Arthur and George were very close friends. They may well have met earlier: George was originally from South London before moving to Stoke for business reasons, so could well have been a member of the South London Chess Club at the time. He also visited the Divan in 1912 when returning to London to visit his family, so, again, they might have known each other from there. Who knows?

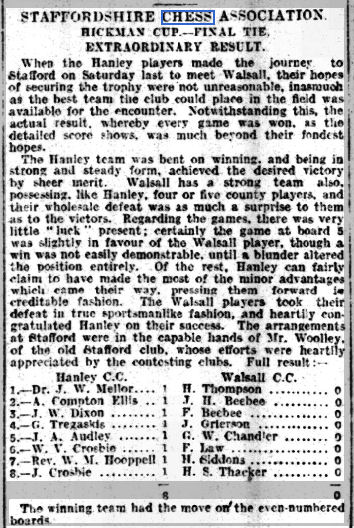

Here they are, in the same team, playing for Hanley in a whitewash over Walsall. Their top board, Joseph William Mellor, was a particularly interesting chap.

Here’s Arthur’s win. He was in trouble most of the way until his opponent went wrong right at the end.

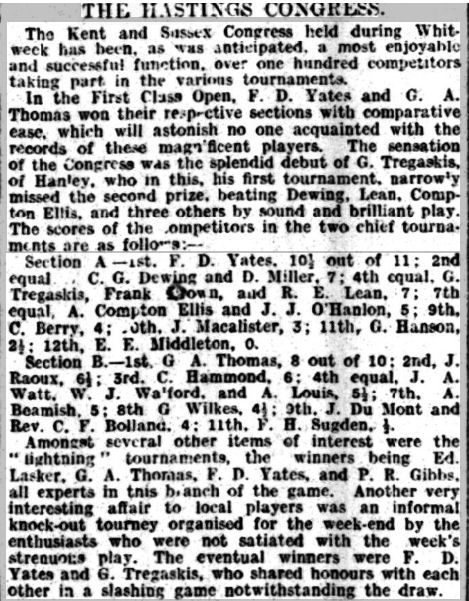

The Kent and Sussex tournament took place over Whitsun at Hastings in 1913. Arthur and George travelled down together, and were both placed in the First Class A tournament.

In his first round game against Inland Revenue man David Miller, Arthur switched from his usual e4 to d4, essaying the Colle-Zukertort Opening. It didn’t go well.

Arthur had beaten George in a club match, and, when they were in the same team, played on a higher board, but here it was Tregaskis who came out on top after his opponent miscalculated a tactical sequence.

Here’s how it ended up.

Unsurprisingly, the masters, Yates and Thomas, outclassed the opposition, who were mostly, with the exception of Middleton and Sugden, strong club players.

A remarkable performance, though, by George Tregaskis in his first tournament, but perhaps slightly disappointing for Arthur Compton Ellis, whose progress seemed, temporarily, to have slightly stalled. Perhaps he needed, as chess teachers always tell their young pupils, to slow down and control his impulses.

With two young and talented new players in their ranks, the future for Staffordshire chess was looking bright. Hanley, after a lapse of three years, won the North Staffordshire League, ‘due in no small measure to the fact that the usual team was greatly strengthened by the inclusion of Mr. A. Compton Ellis, whose enthusiasm for the royal game is unlimited’, according to the Staffordshire Sentinel (4 June 1913).

But then, on 9 July: ‘Local players will hear with much regret that, owing to professional and business reasons, Messrs. A. Compton Ellis and G. Tregaskis have found it necessary to sever their connection with this district.’

George’s work took him to Bristol, as you’ll find out in a future Minor Piece. Arthur returned home to South London. Had he not wanted to remain in Stoke with his friend? Had his teaching work not gone as he’d hoped? We’ll never know.

The two friends kept in touch, playing two correspondence games, one with each colour, over the summer. Although he’d now left the area, Arthur kept in touch with the local paper, followed their chess columns, and submitted these games for publication.

In his game with White, Arthur experimented on move 6, unwisely following a Blackburne game, and, by the next move had a lost position. George concluded brilliantly.

In the game with colours reversed, Tregaskis improved on an Alapin game from the previous year, but went wrong in the ensuing complications. He then resigned a drawn position, missing the saving clause. Ellis’s opponents seemed to have a habit of resigning level positions!

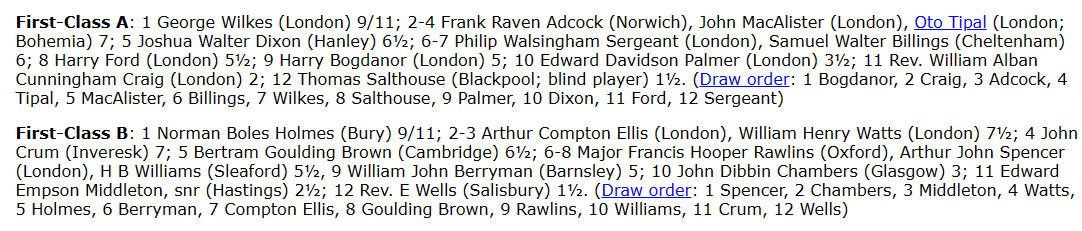

The 1913 British Championships took place in Cheltenham. Arthur Compton Ellis took part again, playing in the First Class B section, where he scored a half point more than the previous year.

This left him in second place behind his Lancashire contemporary Norman Boles Holmes. George Tregaskis wasn’t playing, but you’ll see his other Hanley friend, Joshua Walter Dixon, there in First Class A. Unfortunately, the BCM failed to publish crosstables of these events.

Both Dixon and Ellis scored other successes there: Joshua won two problem solving competitions, while Arthur, although he only finished 7th in the handicap tournament, won a prize in a Kriegspiel (‘a peculiar, and modern, form of chess, unknown to more than 99 per cent. of chess players’) event.

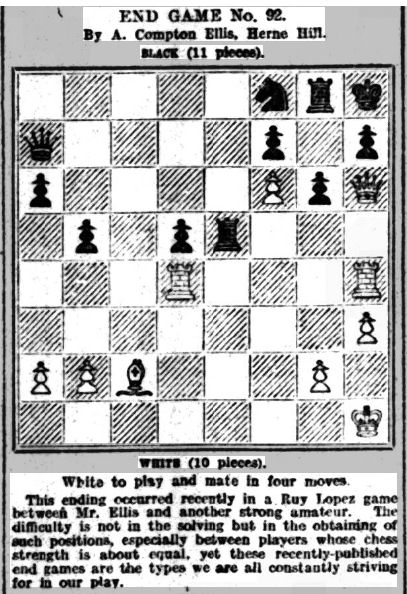

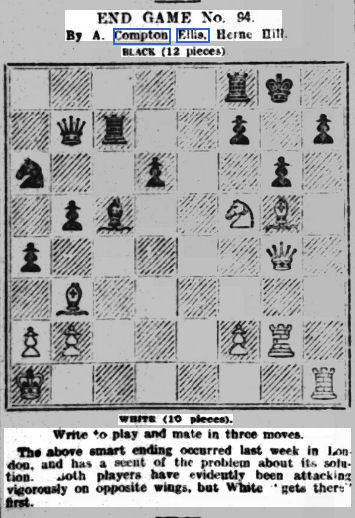

Returning to London, Arthur Compton Ellis submitted two puzzles based on his games to the Staffordshire Sentinel. (The chess editor preferred to remain anonymous: perhaps it was Joshua Walter Dixon.)

It shouldn’t take you too long to find the mate in 4 here.

Two weeks later he offered a mate in 3, which has, although he seemed not to notice, two solutions, both involving attractive (but different) queen sacrifices. Can you find them both?

On 13 September Alekhine, on a brief visit to London, agreed to play a simul at the Divan in the Strand. Arthur, of course, was there.

He lost a pawn and was slowly ground down, but did anyone spot he had a fleeting opportunity for a draw in the pawn ending?

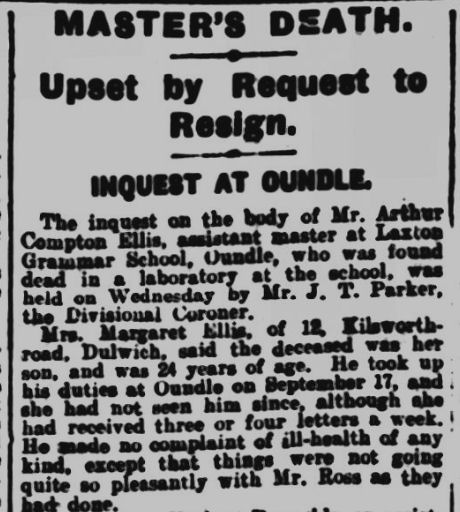

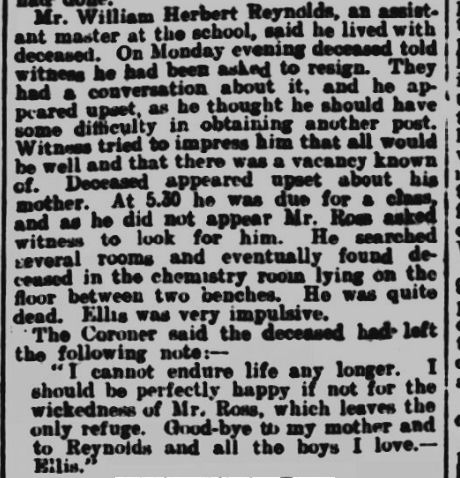

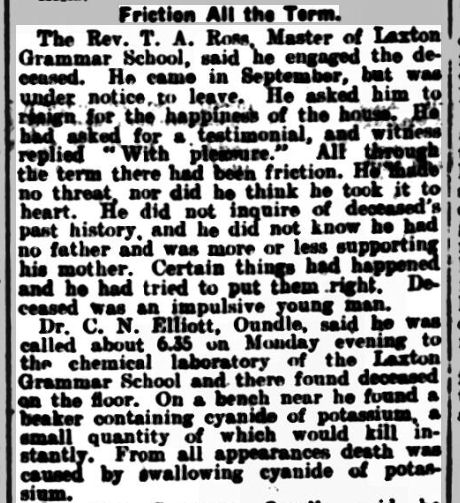

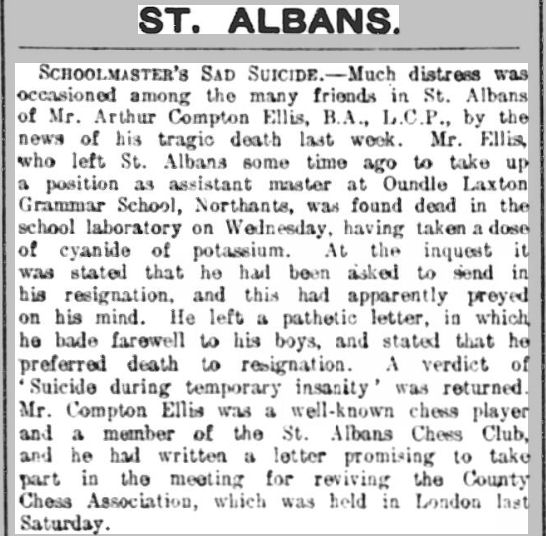

The following Monday he left London. He had a new job as an Assistant Master at Laxton Grammar School, part of the same foundation as Oundle School, but catering for local boys.

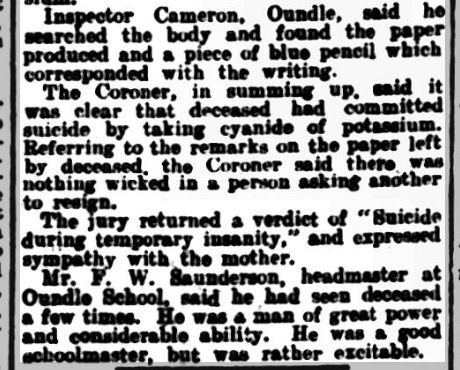

He soon encountered problems there, coming into conflict with the Headmaster, Rev Thomas Harry Ross. In November he was asked to hand in his notice.

What a tragic end to a short but eventful life. A life that promised much but ended far too soon. A man of great power and considerable ability. An impulsive young man. I think you can see that in his chess as well: at times brilliant, at times speculative, but almost always entertaining. You can also see how well he was thought of by his chess friends. Great power and considerable ability, yes, and also enthusiasm, energy and charisma. Looking back from a 2020s perspective you can perhaps see elements of ADHD and bipolar disorder, which tends to manifest itself between the ages of 20 and 25. Could Laxton have treated him better? Undoubtedly. You can only hope that, these days, someone like Arthur Compton Ellis would be better understood.

If he and his mother had chosen to remain in Kew, perhaps the history of chess in Richmond would have been very different. Had he devoted the next half century to playing and organising chess, you might have seen him as a British Championship contender, and perhaps an organiser of major chess events in my part of the world. If he’d lived a long life he might even have met me, and perhaps my life would have been different. I’d like to think that, as the founder of Kew Chess Club, which later merged with Richmond, some part of his spirit lives on in today’s Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club. Spare a thought for the short but frenetic life of a true chess addict: Arthur Compton Ellis.

There are a few loose ends to tie up. Arthur’s nemesis, Rev Thomas Harry Ross, in the years between the two World Wars, was Rector of Church Langton with Tur Langton and Thorpe Langton, where he would have ministered to the relations of Walter Charles Bodycoat, and perhaps to my relations as well. I’ll take up the story of Arthur’s friend George Tregaskis in a later article.

There’s one other mystery to look at.

St Albans? There’s nothing online yet about chess in St Albans at that time. He seems to have been in South London with his mother between leaving Stoke and arriving at Oundle. I suppose he might have been there late 1912/early 1913, when there was a gap of a few months in his chronology. We can also go back a few years, to May 1907, when AC Ellis, first from St Albans, then from Swindon, who was solving chess problems in the Bristol Times and Mirror. Was that our man? Was he, perhaps, in those towns for teaching practice? Who knows?

There’s an implication that the family were having some sort of financial problem. There’s also a slight mystery in that the coroner’s report gives his mother’s address as 12 Kilsworth Road Dulwich, while his probate record (he left £560 17s) gave his address as 12 Pickwick Road Dulwich Village. I can’t locate Kilsworth Road (or anything similar) so it may well be a mistake for Pickwick Road, which could also be considered to be in Herne Hill. By 1921 Margaret had returned to Kew, living on her own at 333 Sandycombe Road, just the other side of the railway from where she’d been living ten years earlier. It’s not at all clear when she died: there’s no death record close to Richmond and the family hasn’t been researched. There’s a possible death record in Islington in 1930: perhaps she’d returned to the area where she spent the first part of her life.

Join me again soon for some more Minor Pieces investigating the lives of some of Arthur Compton Ellis’s chess opponents.

Sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

chessgames.com

BritBase (John Saunders)

Yorkshire Chess History (Steve Mann)

Various other sources quoted and linked to above

2 thoughts on “Minor Pieces 54: Arthur Compton Ellis”