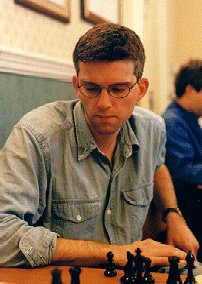

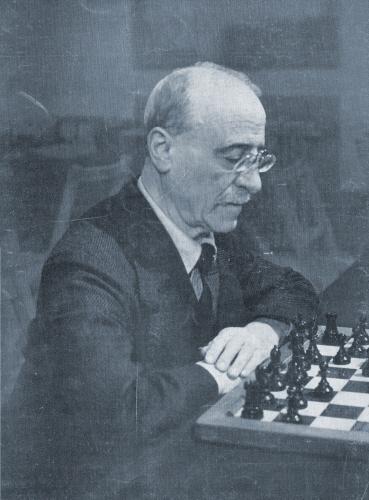

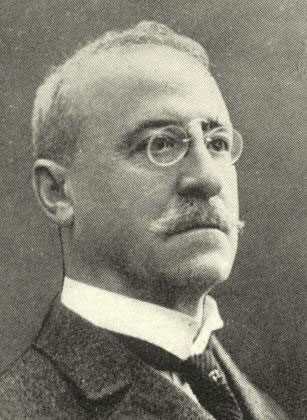

BCN remembers CGM Keith Richardson who passed away on Monday, April 10th, 2017.

Keith Bevan Richardson was born in Nottingham, on Thursday ,April 2nd 1942. On this day : The comedy film My Favourite Blonde starring Bob Hope and Madeleine Carroll was released.

Keith’s parents were Arthur (30) and Hilda May (née Nicholls, 25). He married Sandra Sowter on the 11th of September 1971 in Sutton Coldfield, Warwickshire. They had two children, Neil and Ian. They lived at 19, The Ridings in Camberley, Surrey.

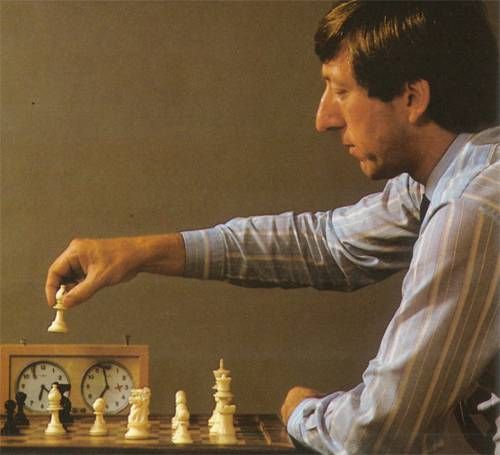

Sadly, Keith was diagnosed in the 1990s with Parkinson’s disease and became unwell whilst playing in a chess tournament in Cannes in April 2017 and passed away on the 10th of May 2017. Keith was 75. He continued to actively play chess into his final year.

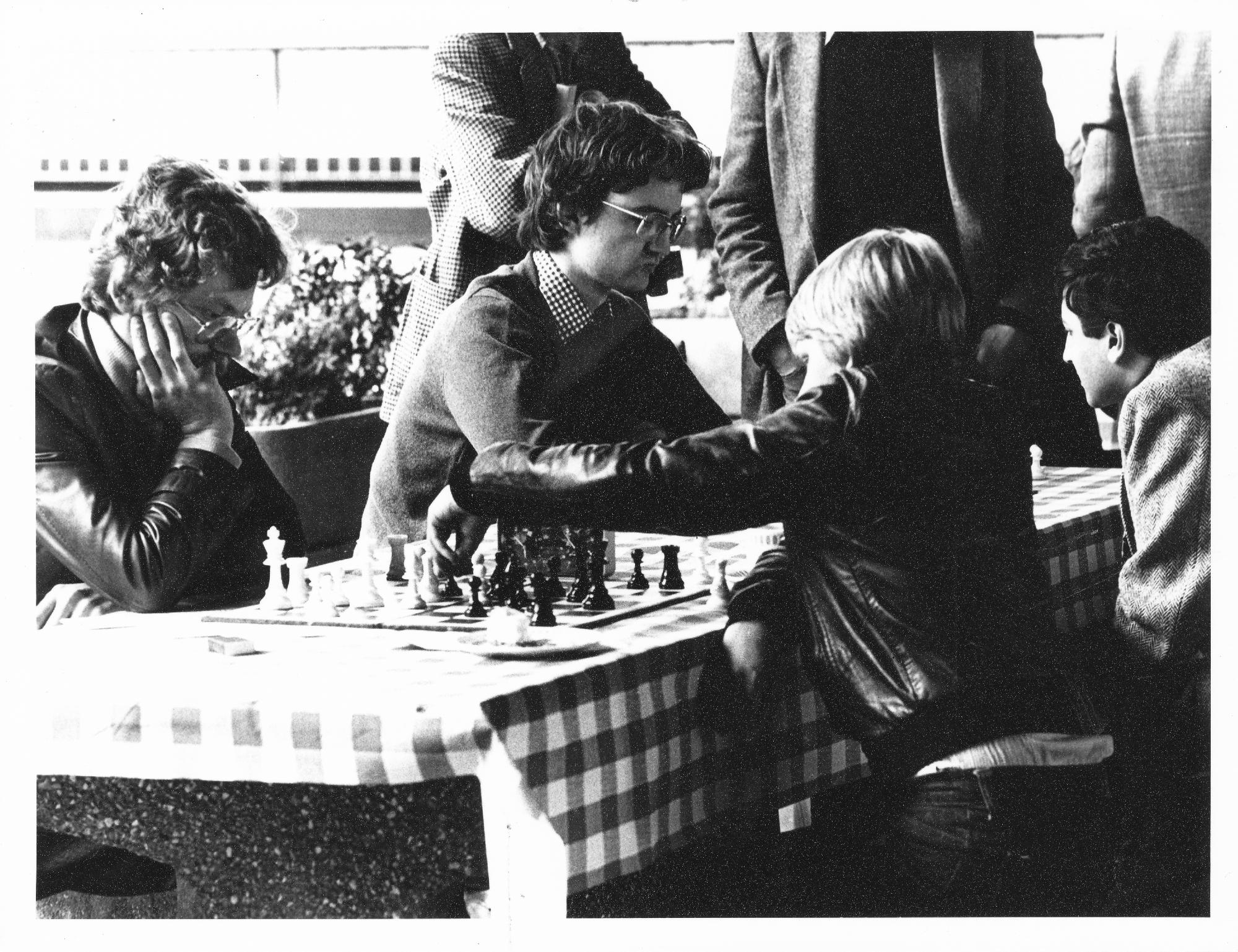

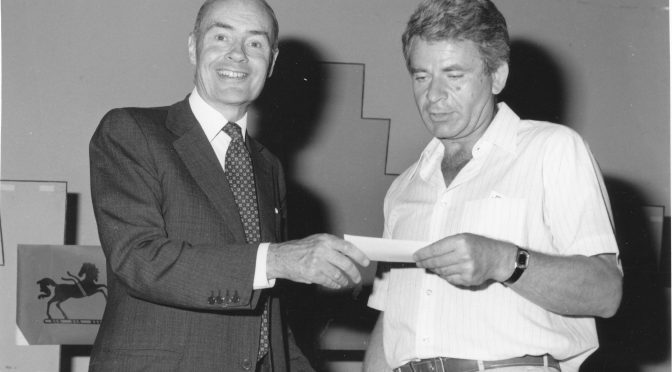

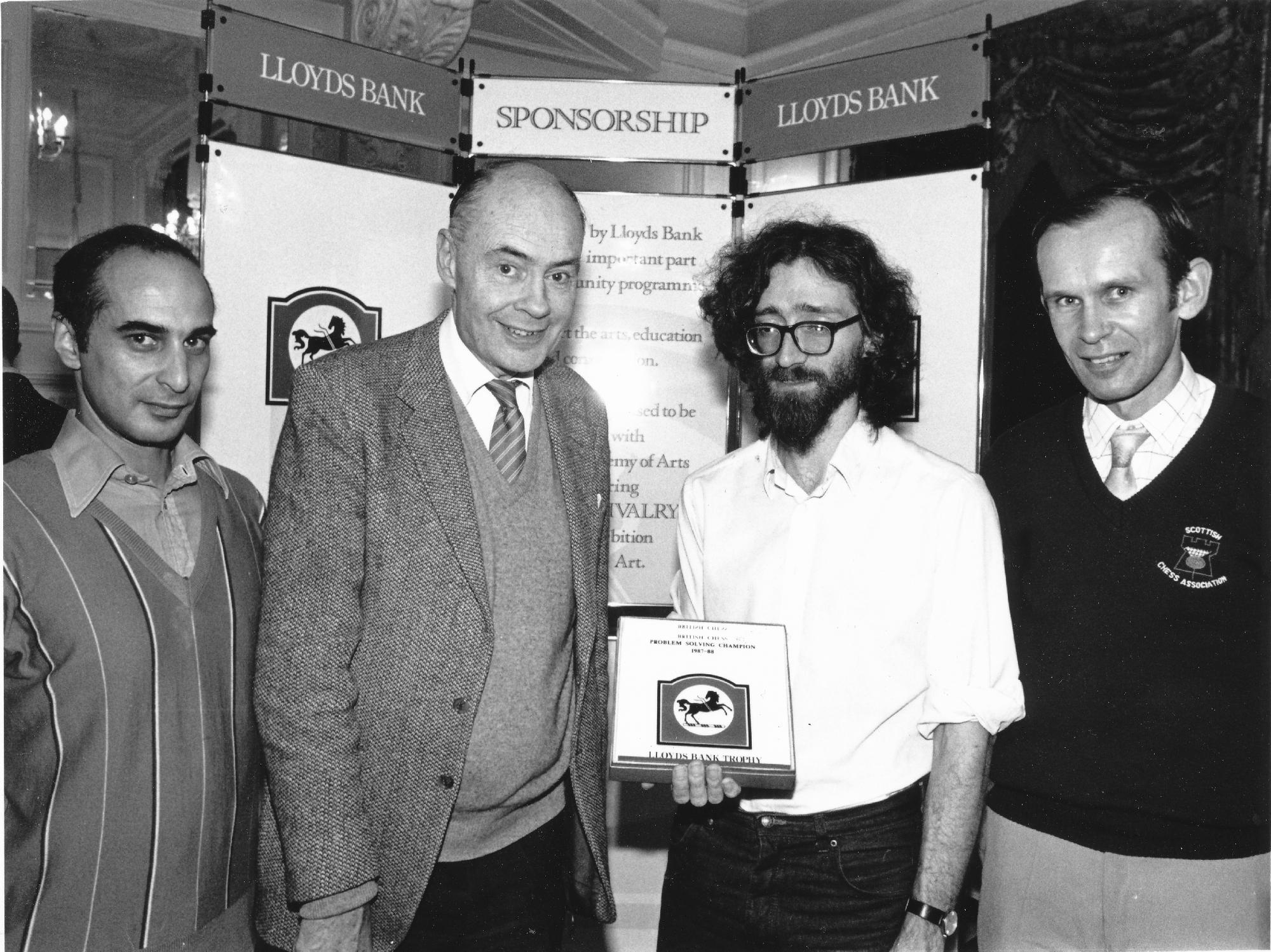

Keith was the Treasurer of the Friends of Chess during the period known the English Chess Explosion (late 1970s and 1980s).

Keith received the ECF President’s Award in 2015 for services to the management of the BCF Permanent Invested Fund (PIF) together with Dr. Julian Farrand and Ray Edwards.

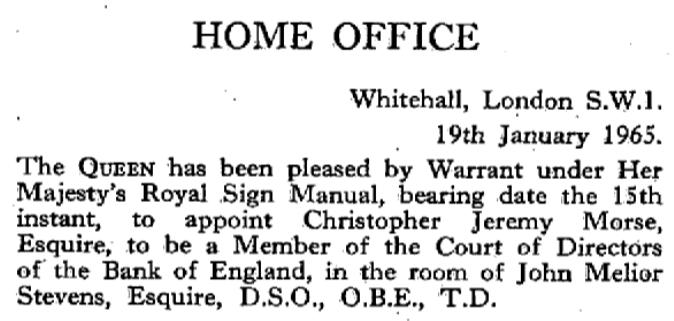

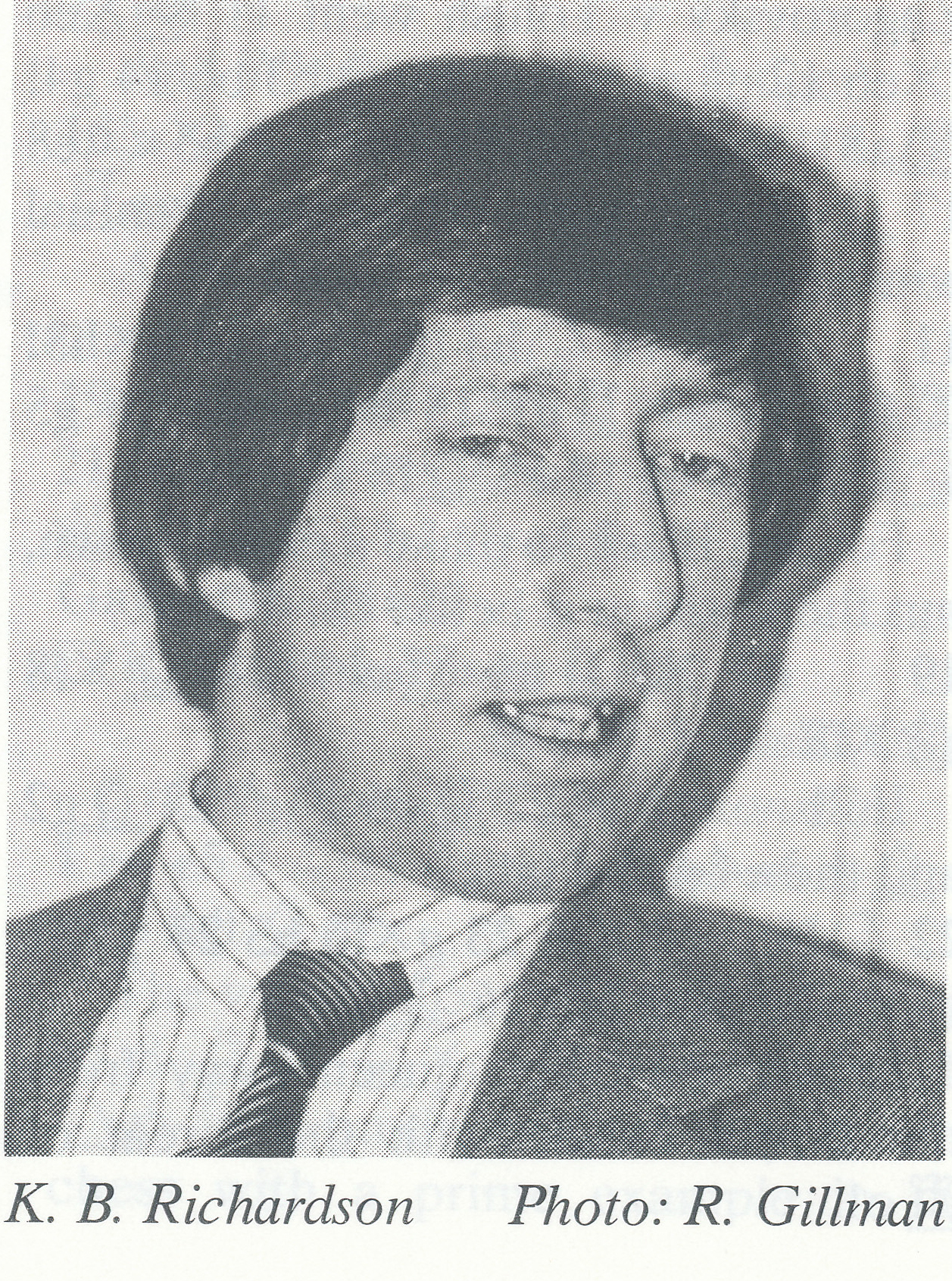

From CHESS, Volume 41 (1975), Numbers 729-730 (September), pp. 380 the news of Keith’s success was initially reported:

“BRITAINS’ FIRST CHESS GRAND MASTER

The first grand master title to be won by a British player has been achieved in the field of correspondence chess by Keith B. Richardson, aged 33, of Camberley.

The title of Correspondence Chess grand master is awarded by the lnternational correspondence Chess Federation. Keith Richardson fulfilled the norm by sharing third place in the final of the 7th World Correspondence Chess Championship with a score of 11 points from 16 games. The tournament began in February 1972 and results of the last adjudicated games were recently announced making J. V. Estrin U.S.S.R. first with l2 points; J. Boey Belgium scored 11.5; K. B. Richardson G.B. and Dr. V. Zagorovski U.S.S.R. 11.

There are only 25 Correspondence Chess Grand masters throughout the world.”

This was followed in the next month’s issue by a correction and more depth in CHESS, Volume 41 (1975), Numbers 731-732 (October), pp. 30-31:

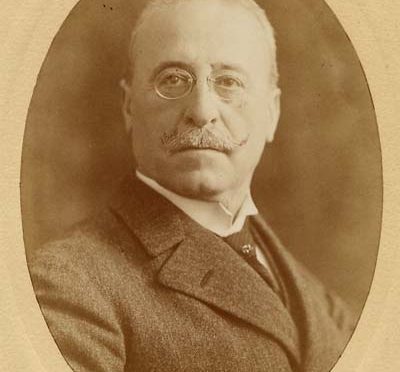

“K. B. Richardson, though the first Britain to become a grand master by play was preceded by Comins Mansfield as grandmaster of problem composition, a title he gained in 1972. Our report last month did not make this clear.

Keith B. Richardson was born 2 April 1942 and was educated at Nottingham High School. At 16, he passed Grade 8 in Royal

Schools of Music at pianoforte. At Durham University, he obtained a B.A. in French and German and was awarded the University Palatinate (equal to a ‘blue’) in cricket and fives. He could have become a professional cricketer or a concert pianist but

made his career instead with Barclays Bank which brought him to London and a home in Camberley, Surrey, where he has settled down with his wife, Sandra (from Sutton Coldfield!). They now have two baby sons, Neil aged three years and Ian who is only two months old – both born since the final of the 7th World Correspondence Chess Championship began.

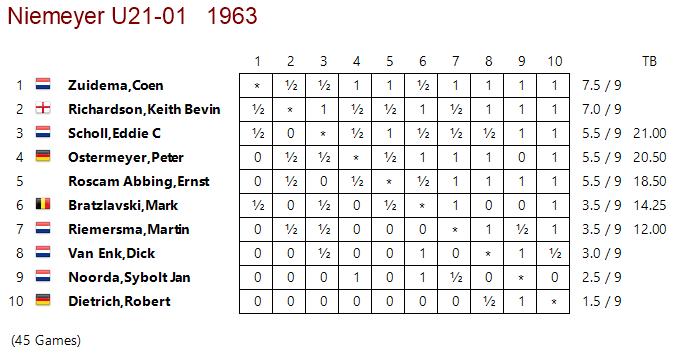

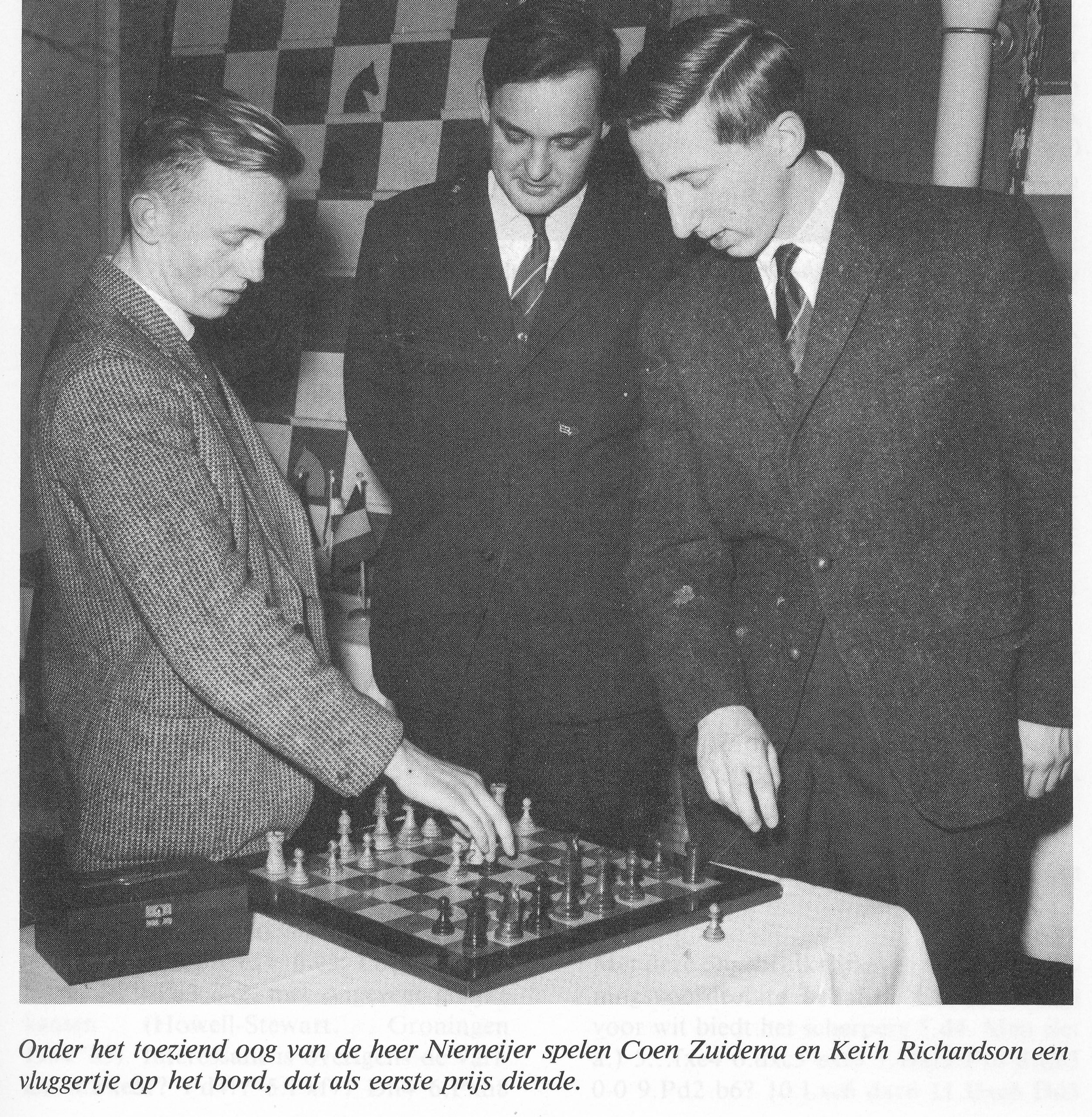

Keith’s other interests include bridge and squash. He plays squash for his bank and is Secretary of the London Squash League. As a young chess player, Keith won the Notts. under l4 Championship, held the Notts. under l8 Championship for four years and the Notts. Championship for two years and was British Junior Champion in 1962. In 1963, he was Durham County Champion and joint winner of the British Universities’ Championship which he won outright the following year. He was twice captain of the British Universities Students’ Olympiad team. He held the Midlands Championship (Forrest Cup) for three years and was joint London Champion and London Banks’ Champion in 1970 but has been content to hold the latter title since then and concentrate on correspondence chess.

In 1964, Keith Richardson was runner up for the British Correspondence Chess Championship and at the same time won a Master Class tournament of the lnternational Correspondence Chess Federation (I.C.C.F.) which qualified for a place in the World C.C. Championship semi-final. He came second in the 1965-67 semi-final and tried again in the 1968-71 event which he won. At the same time, he was representing Great Britain on Board 5 in the 1965-67 I.C.C.F. Olympiad Preliminary and on Board 4 in the 1968-71 event. His score of 5 points from 7 games helped the British team to win its section in the 1968-71 Preliminary and qualify for a place in the I.C.C.F. Olympiad Final which started in 1972. When Keith began play in the World C.C. Championship Final involving l6 tames, he was also asked to take Board 3 in the Olympiad Final involving another 9 games.

He accepted – a mistake which might possibly have cost him the World C.C. Championship! His next assault on the World title will be in 1979 and in the meantime he plans to play in the next I.C.C.F. Olympiad Preliminary and write a book on the 7th World C.C. Championship.

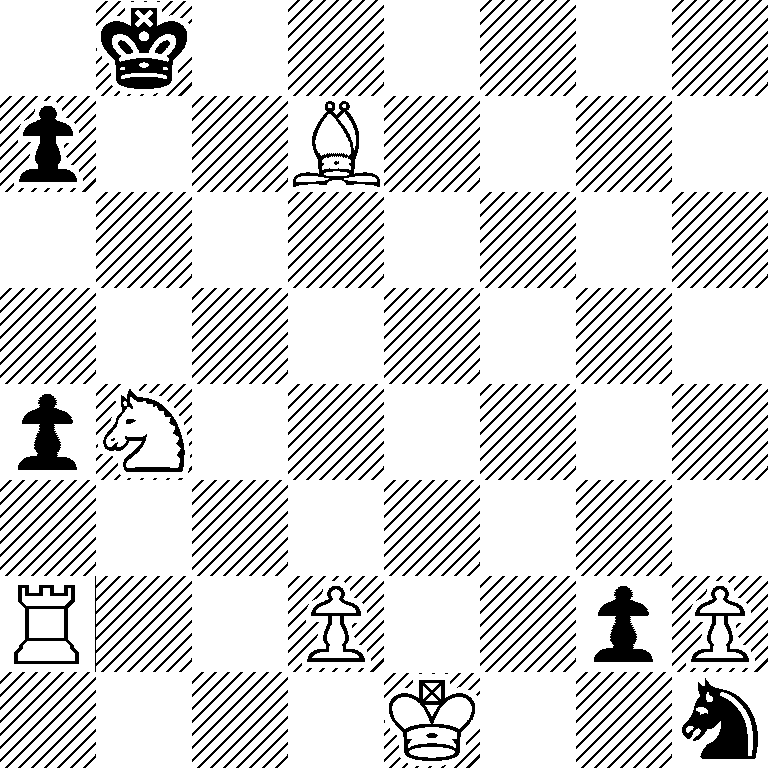

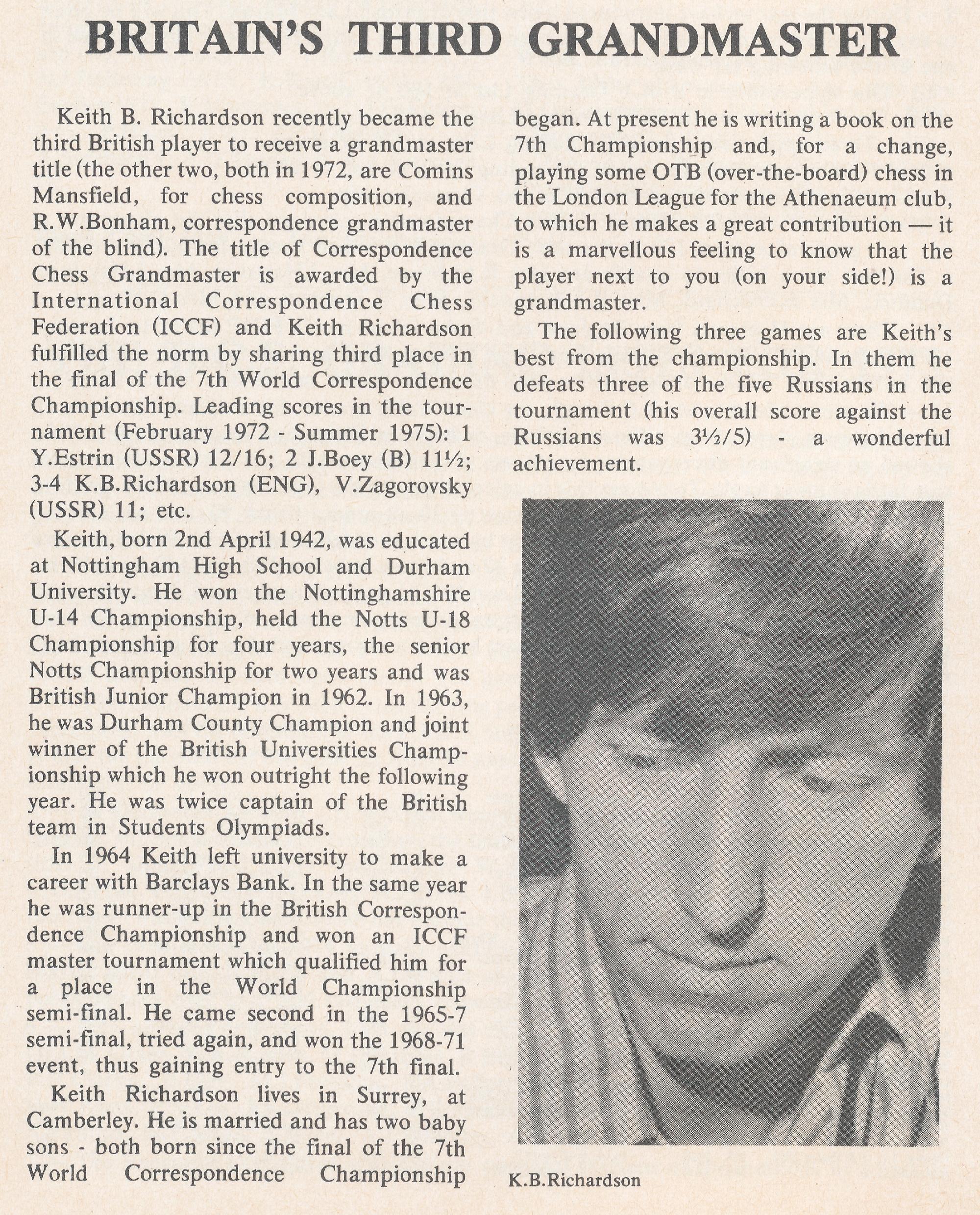

In this position, with Black in Zugzwang, the game went for adjudication (after more than three years’ play, a very necessary evil):

“In order to substantiate White’s claim for a win, it was necessary to submit three pages of analysis proving that every possible move loses for Black. If the knight moves, White’s king claims an entry. If Black moves the bishop along the a7-g1 diagonal, White plays Ba5. If the Black bishop moves on the d8-a5 diagonal, White plays Bd4 : KBR”

The game was adjudicated a win for White. This was only defeat inflicted upon the new World Champion.

This article was followed (with some glee no doubt) by an article in British Chess Magazine, Volume LIXIV (95, 1975), Number 12 (December), page 526 as follows:

“Keith B. Richardson recently became the third British player to receive a grandmaster title (the other two both in 1972, are Comins Mansfield for chess composition’ and R.W. Bonham’ correspondence grandmaster of the blind). The title of Correspondence Chess Grandmaster is awarded by the International Correspondence Chess Federation (ICCF) and Keith Richardson fulfilled the norm by sharing third place in the final of the 7th World Correspondence Championship. Leading scores in the tournament (February 1972 – Summer 1975): 1. Y. Estrin (USSR) 12/16; J.Boey (B) 11.5; 3-4 K.B. Richardson (ENG), V. Zagorovsky (USSR) 11; etc.

Keith, born 2nd April1942, was educated at Nottingham High School and Durham University-. He won the Nottinghamshire U-14 Championship, held the Notts U-18 championship for four years, the senior Notts Championship for two years and was British Junior Champion in 1962. In 1963, he was Durham County Champion and joint winner of the British Universities Championship which he won outright the following year. He was twice captain of the British team in Students Olympiads.

In 1964 Keith left university to make a career with Barclays Bank. In the same year he was runner-up in the British Correspondence Championship and won an ICCF master tournament which qualified him for a place in the World Championship final. He came second in the 1965-7 semi-final, tried again, and won the 1968-71 event thus gaining entry to the 7th final.

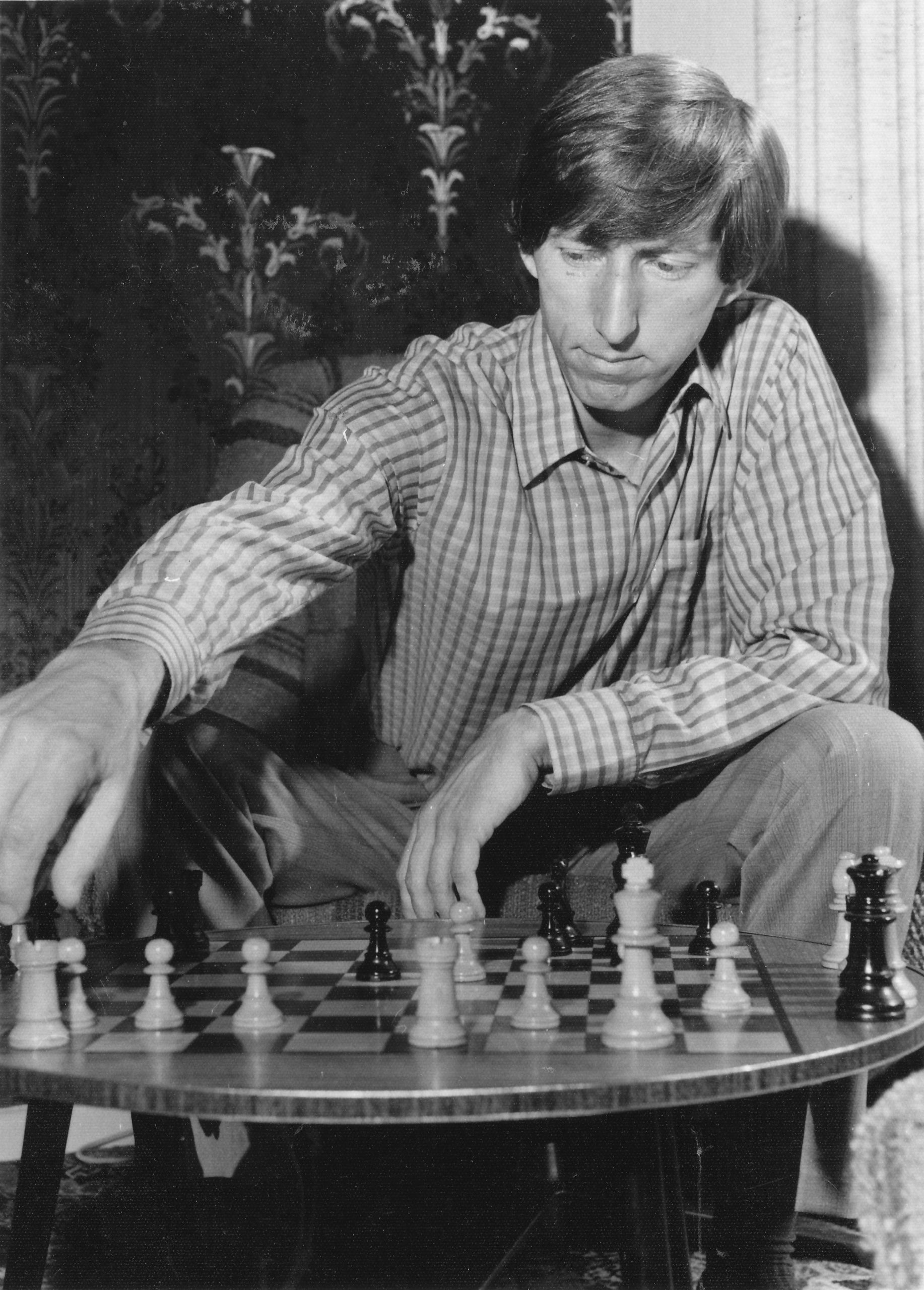

Keith Richardson lives in Surrey at Camberley. He is married and has two baby sons – both born since the final of the 7th World Correspondence Championship began. At present he is writing a book on the 7th Championship and, for a change playing some OTB (over-the-board) chess in the London League for the Athenaeum club, to which he makes a great contribution – it is a marvellous feeling to know that the player next to you (on your side!) is a grandmaster.

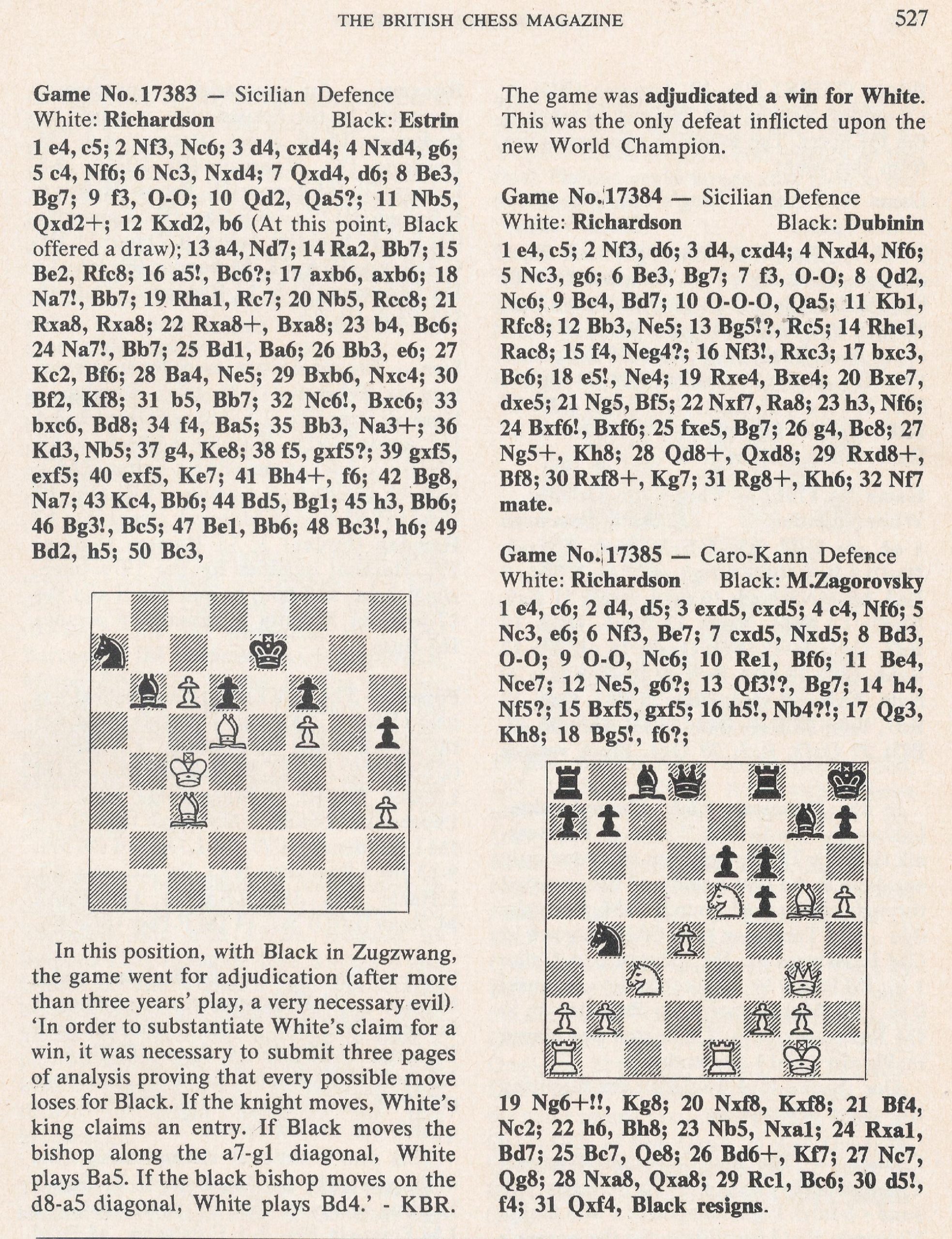

The following three games are – Keith’s best from the -championship. In them he defeats three of the five Russians in the

tournament (his overall score against the Russians was 3.5/5 – a wonderful achievement.”

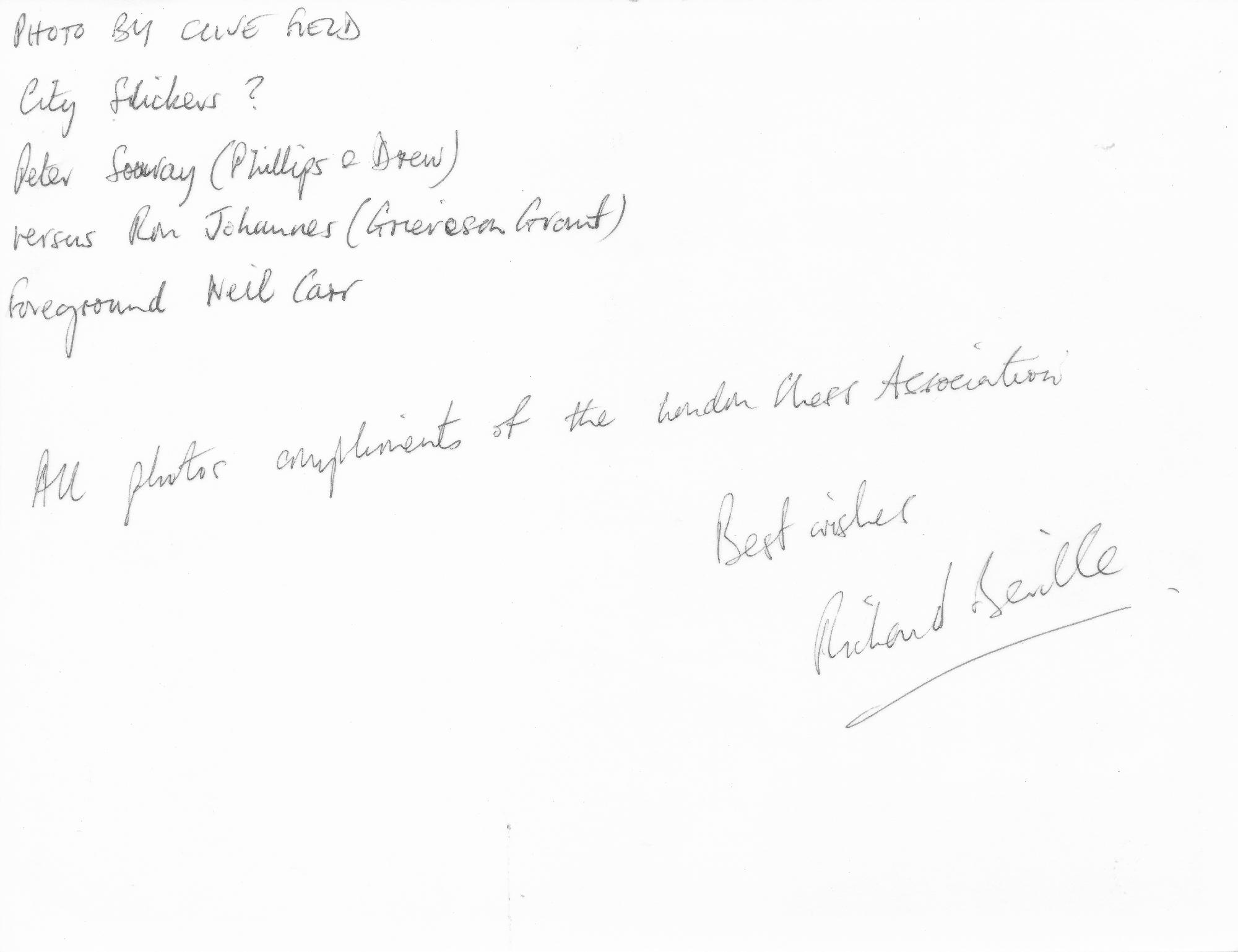

and here is the printed version of the above report:

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

“English player. International Correspondence Chess Grandmaster (1975), bank manager. Around 1961 Richardson decided that over-the- board play, which had brought him some successes as a. junior, would interfere with his professional career and he took to postal chess instead. His best performance in this field was his sharing of third place with Zagorovsky after Estrin and Boey in the 7th World Correspondence Championship, 1968-71. ”

In October 1984 Keith took part in the A. E. Axelson Memorial tournament organised by the Swedish CC Committee and with fifteen grandmasters was one of the strongest CC tournaments in history. Keith finished in 11th place ahead of Boey.

In 1991 Jonathan Berry wrote a potted biography in Diamond Dust, International Chess Enterprises, ISBN 1-879479-00-1 as follows :

“Camberley, Surrey, England. Born 2 April 1942. Married with two sons. Bank Manager.

He was British Under-21 Champion in 1962. At Groningen 1962/63, he was placed 2nd in the European Junior Championship. At Bristol 1967 he was equal 5th in the British Championship.

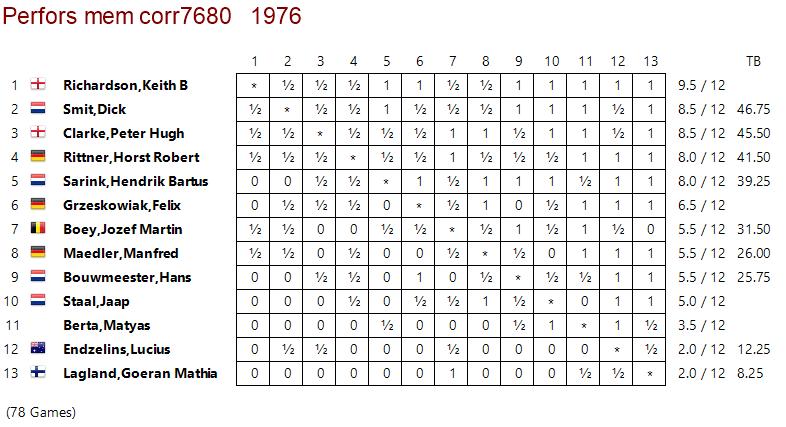

In CC, he gained the IMC in 1968, GMC in 1975. In CC WCh VII, he won the semi-final with 9.5/12, and placed =3rd in the final, 11/16. In CC WCh X, he again tied for third in the final with 10/15. Playing board 3 for Britain in OL-VIII, finals, 1972-76, he scored 7.5/9, the highest score on any board. He won the Prefors Memorial, 1976-1980, 9.5.12”

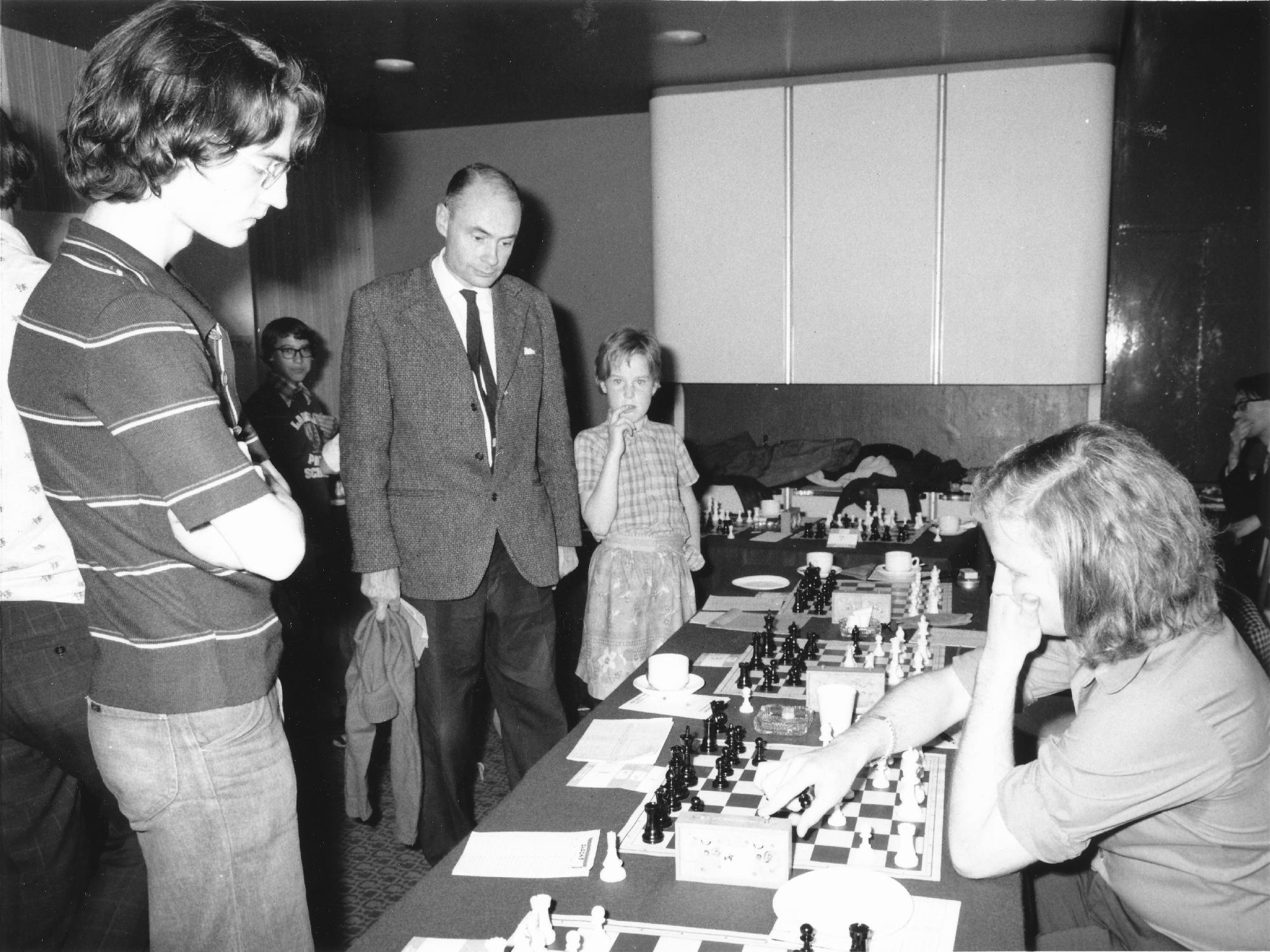

Keith was a founding member of Camberley Chess Club in 1972.

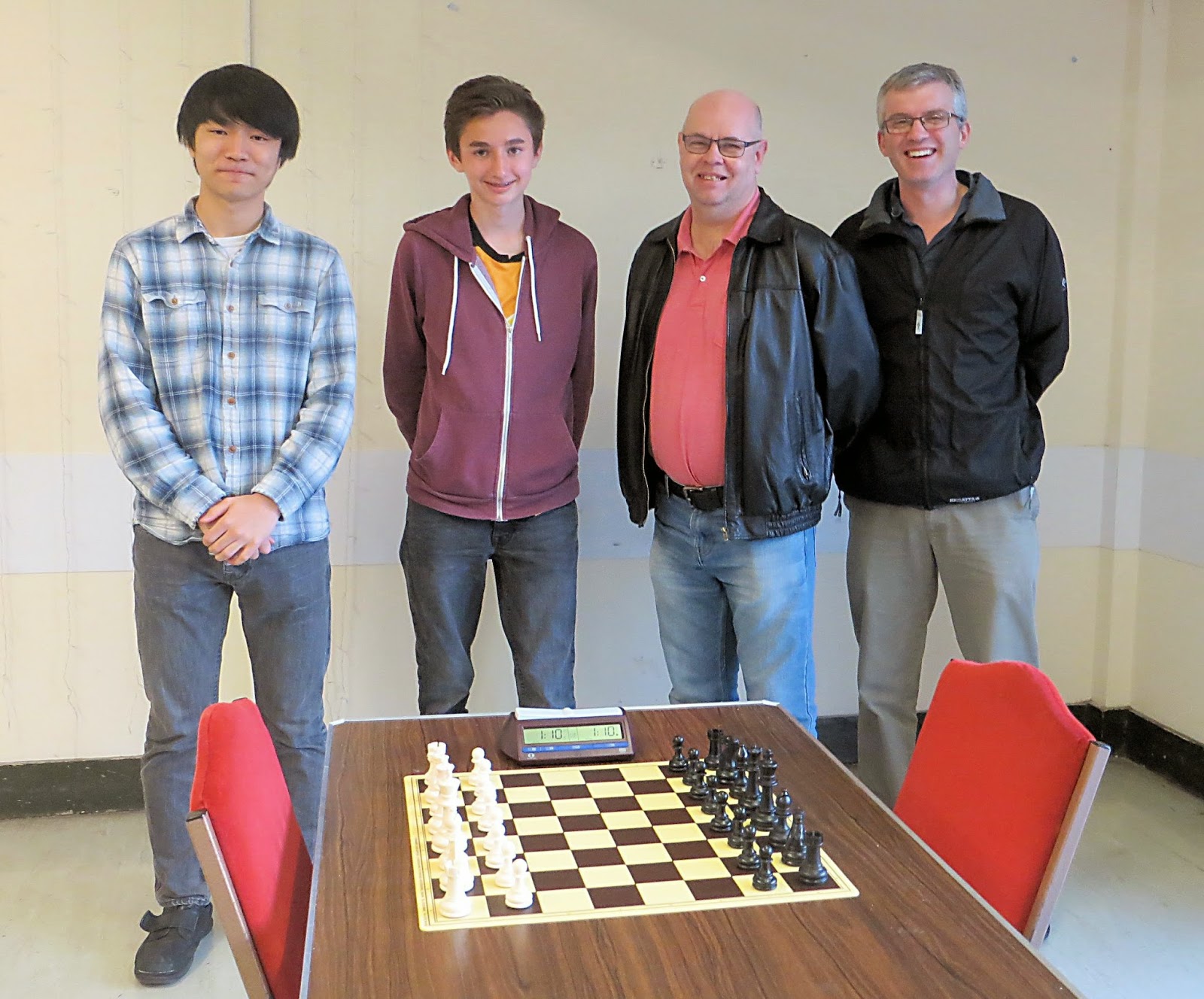

A one-day tournament (The Keith Richardson Memorial) in memory of Keith was started in 2017 and has been held six times in total being played on-line for the first time in 2021 and then reverting to OTB in 2022.

From Chessgames.com :

“Keith Bevan Richardson was born in Nottingham, England. Awarded the IMC title in 1968 and the GMC title in 1975, he finished 3rd= in the World Correspondence Championships of 1975 and 1984.”

Here are his games from chessgames.com

An obituary from Ray Edwards / ECF.

Here is an excellent biography by Peter Rust from the web site of the Hamilton Russell Cup

Barclay’s Bank pay tribute to Keith on the corporate site.

Here is an entry from the Belgian chess history web site.