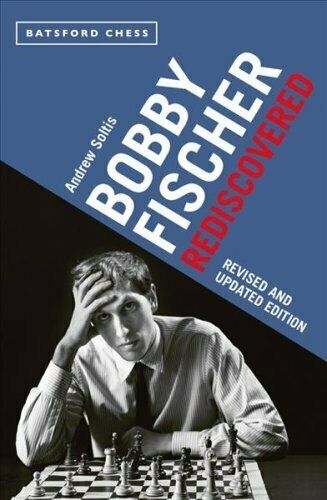

“International Grandmaster Andrew Soltis is chess correspondent for the New York Post and a very popular chess writer. He is the author of many books including What it Takes to Become a Chess Master, Studying Chess Made Easy and David vs Goliath Chess.”

From the Batsford web site :

“Nearly 30 years since his last chess game, Bobby Fischer’s fame continues to grow. Appearing in Hollywood movies, documentaries and best-selling books, his life and career are as fascinating as they ever were and his games continue to generate discussion. Indeed, with each new generation of computer, stunning discoveries are made about moves that have been debated by grandmasters for decades.

International Grandmaster Andrew Soltis played Fischer and also reported, as a journalist, on the American’s legendary career. He is the author of many books, including Pawn Structure Chess, 365 Chess Master Lessons and What it Takes to Become a Chess Master.”

No chess library is complete without a copy of Bobby Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games. If you’re interested in Fischer, and you certainly should be, you’ll also want a games collection looking at the whole of his career through 21st century eyes.

There are several to choose from and, I guess, you’d find a comparative review useful, but I’m not in a position to do that. All I can do at the moment is comment on the book in front of me.

This is a new edition of a book first published in 2003. I don’t have the original to hand to make a comparison. Seven games have been added, making a total of 107: mostly Fischer wins but a few draws are also included.

Here’s Soltis, from his Author’s Note:

Thirty years later (in 2002), I looked at Fischer’s games for the first time since they were played. What struck me is that they fell into two categories. Some were, in fact, overrated. But many more were underrated – if known at all. And his originality, so striking at the time, had been lost with time. It seemed to me Fischer deserved an entirely new look.

Soltis identifies several recurring themes in Fischer’s games. By emphasizing these themes in his annotations he provides instructive lessons for his readers.

“To get squares you gotta give squares”, as Fischer himself said.

Ugly moves aren’t bad.

Material matters. Soltis adds here that Fischer was a materialist: most of his great sacrificial games were played before he was 21.

Technique has many faces. Fischer was equally good at both obtaining and realizing an advantage – two different skills – often by converting one type of advantage to another.

Soltis concludes his note as follows:

Since the first edition of this book, Fischer’s games have been re-analyzed by many others, including Garry Kasparov, with the help of computers. Everyone finds something new – hidden resources, nuances and errors in earlier annotations. This is almost certain to go on with each new generation of stronger analytic engines. I have made extensive revisions since I tackled these games in 2003. But I suspect Fischer’s moves, like his life, will remain a source of fascination – if not mystery – well into this century.

One of the big plusses of this book is that the author was there at the time: he knew Fischer and all his contemporaries. Each game is preceded by a brief introduction putting it in context, often with the inclusion of a timely anecdote revealing an aspect of Fischer’s complex and contradictory personality.

If you’re familiar with Soltis’s style of annotation you’ll know what to expect: detailed annotations, using words to tell a story and only including variations where necessary: no reams of unexplained computer-generated analysis here.

Have a look at how Soltis deals with a game you might not have seen before: the lightweight encounter Fischer – Naranja, played in the Philippines in 1967. (MegaBase thinks this is from a simul, whereas Soltis describes it as one of a series of clocked games.) Note that these are just the more pertinent of his annotations.

1. e4 c5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. Nge2 e5

The principled reply, as the Russians would say. It was unfairly criticized at the time for surrendering d5.

4. Nd5 Nf6 5. Nec3 Be7 6. Bc4 O-O 7. d3 h6?

Black wanted to avoid 8. Nxe7+ and 9. Bg5 but this puts his king on the endangered species list. Today’s grandmasters get close to equality with 7… Nxd5 8. Bxd5 d6 and a trade of bishops after Bg5.

8. f4! d6?

Black must exchange on f4.

9. f5!

This strategically decides the game. White stops …Be6 and sets the stage for a decisive advance of the g-pawn.

9… b6

It was too late for 9… Nxd5 10. Nxd5 Bg5 because 11. Qh5! Bxc1 12. Rxc1 threatens 13. f6 with a quick mate. … But Black should at least eliminate the bishop with 9… Na5.

10. h4!

A striking move which prepares g4-g5, with or without Nxe7+ and Qh5. The key variation is 10… Nxd5 11. Bxd5! Bxh4+ and now 12. g3! Bxg3+ 13. Kf1, à la King’s Gambit, gives an overwhelming attack.

10… Bb7 11. a3!

Another exact move, preserving the bishop against 11… Na5 and stopping … Nb4. The significance of this is shown by 11. Nxf6+ Bxf6 12. Qh5? when Black has 12… Nb4! with good chances, e.g. 13. Bb3 d5 14. g4 c4!.

11… Rc8 12. Nxf6+! Bxf6 13. Qh5

13… Ne7

Black had to do something about 14. g4 and 15. g5, and this enables him to shoot back with 14. g4 d5.

14. Bg5!

Another terrific move, threatening Bxf6. Of course, 14… hxg5 15. hxg5 is taboo because of mate on the h-file.

14… d5 15. Bxf6 dxc4 16. Qg4 g6 17. dxc4!

There must have been a huge temptation to try to finish the game off in style – particularly after White saw 17. Qg5 hxg5?? 18. hxg5 and Rh8#…. But again … Nxf5 bursts the bubble: 17. Qg5? Nxf5! and now 18. Bxd8 hxg5 19. Bxg5 Nd4 is a roughly equal ending, or 18. exf5 hxg5 19. hxg5 Qxf6.

17… Qd6

This acknowledges defeat but 17… Kh7 would have breathed life into 18. Qg5!!:

(a) 18… Re8 19. h5! hxg5 20. hxg6+ and Rh8#

(b) 18… Rc6 19. h5! (the fastest) Nxf5 20. hxg6+ Kg8 21. Nd5! and

(c) 18… Ng8 19. Bxd8 hxg5 20. hxg5+ Kg7 21. f6+ and mates

18. Bxe7!

Black’s last move was designed to meet 18. Qg5 with 18… hxg5 19. hxg5 Qxf6!. So Fischer decides to cash in.

18… Qxe7 19. fxg6 fxg6 20. Qxg6+ Qg7 21. Qxg7+ Kxg7 22. Rd1 Rcd8 23. Rxd8 Rxd8 24. Nd5 b5 25. cxb5 Bxd5 26. exd5 c4 27. a4 Rxd5 28. Ke2 Rd4 29. Rd1 Re4+ 30. Kf3 Rf4+ 31. Ke3 c3 32. b3 1-0

Nice tactics, to be sure, but Fischer was winning from move 9, and, so Stockfish 13 tells me, had many other ways to bring home the point. Was it really one of his greatest games, then? Or is this not the point of the book?

The third, tenth and thirteenth games from the 1972 Fischer – Spassky match are included, but not, to my surprise, the sixth, one of my favourite Fischer games. Most of the old favourites, though, are included, but all except his most devoted fans will find a few unfamiliar games.

As you would expect, this is a solid book which serves its purpose well. If you want the best of Bobby on your bookshelves you’re unlikely to be disappointed, but you might perhaps prefer to consider his games from a 2020 rather than an updated 2000 perspective. You’ll probably want to look around and decide which of several on the market best suits your requirements.

My main problem is a lack of references: although sources are sometimes given, all too often we read that ‘Botvinnik wrote’ or ‘Boleslavsky said’ without being told where. There are several blank pages at the end of the book which might usefully have been filled by a bibliography.

Nevertheless, I enjoyed the book, which gave me a new insight into Fischer’s games, along with some valuable background information.

Richard James, Twickenham 8th March 2021

Book Details :

- Paperback: 312 pages

- Publisher: Batsford Ltd; 2nd revised edition (5th March 2020)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:184994606X

- ISBN-13:978-1849946063

- Product Dimensions: 15.57 x 2.29 x 23.5 cm

Official web site of Batsford