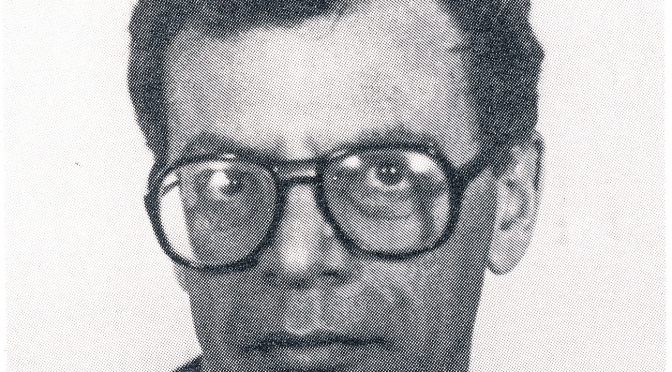

BCN remembers Ken Messere who passed away on Thursday, March 31st 2005 aged 76 in Paris-16E-Arrondissement, Paris, France.

Kenneth Charles Messere was born on Monday, April 16th, 1928 in Richmond-on-Thames, Surrey. His father was Charles (George) Messere (1901-1974) or Eisenberg and aged 26. His mother was Gertrude Marie Newman (1899-1978) and aged 29.

Ken had three siblings: Barbara Marie Messere (1930–2005), Hugh Martin Messere (1932–1985) and Derek R Messere (1934–2012)

Ken attended St. Peter’s College, Oxford from 1946 – 1951 to read philosophy and is reported in the 1951 St. Edmund Hall Magazine, as a member of the Trillick (debating) Society as follows:

‘ That this House would rather be a live Communist than

a dead Democrat.’ The proposer established to his own satisfaction that democracy was founded on ‘selfishness, capitalism and bourgeois hypocrisy.’ He did not satisfy J. F. R. Bonguard of St. Peter’s Hall who opposed, using arguments taken from Hindu philosophy. K. C. Messere of St. Peter’s Hall, spoke third and added some able arguments.

In June 1954 Ken married Mary Elizabeth Humphrey (1929-2003) in Ealing. They had a son Miles Jonathan Messere born in 1964 who passed away in 1965.

Prior the time of his passing his wife Mary was living at 142B, Herbert Road, Woolwich, London, SE18 3PU.

In 1991 he was awarded the OBE (Civil Division) in the Queen’s Birthday honours list. The citation reads: Kenneth Charles Messere, lately Head of Fiscal Affairs Division, OECD, Paris.

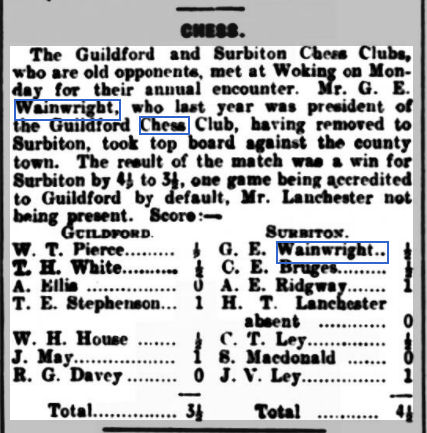

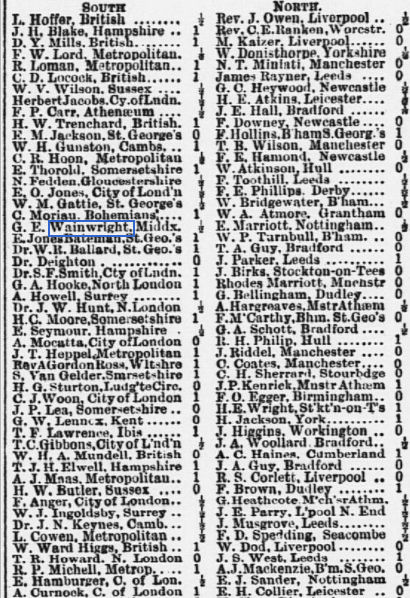

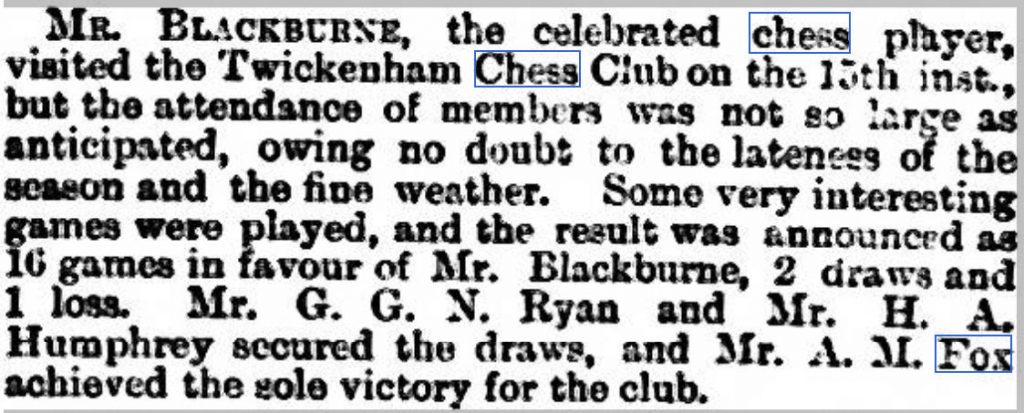

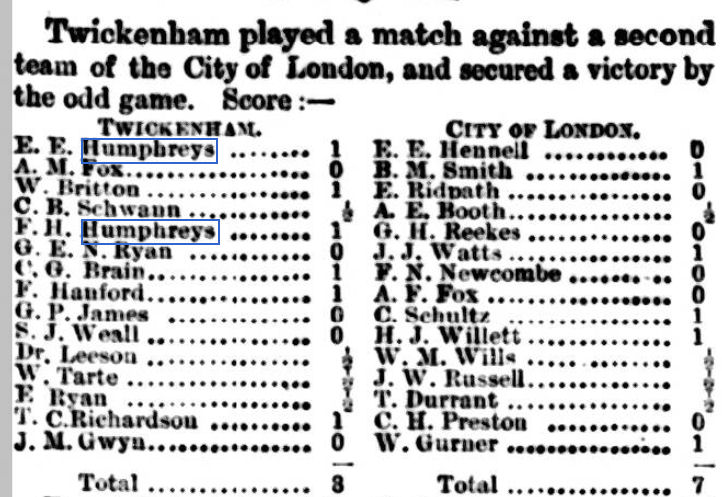

Ken appears each year from 1953 to 1967 in the noted publication Britain, Royal And Imperial Calendars the function of which is to list entries for those engaged in UK public service. He worked for HM Customs and Excise. Prompted by this we consulted the venerable A History of Chess in the English Civil Service by Kevin Thurlow (Conrad Press, 2021) on page 447 and found

“He played for Customs. In 1964, he went to work for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and was head of fiscal affairs from 1971 – 1991. In 1954 he began playing postal chess and became a leading player. He won a semi-final of the 5th World Correspondence Championship (1961 – 64) and became the first English player to compete in a World Championship Final.”

There are 31 games listed at his personal entry at chessgames.com starting with games from 1965.

Chessbase’s Correspondence Database 2020 records 69 games the earliest being from 1958 listing Ken’s federation as being France.

From British Chess (Pergamon Press, 1983) we have this lengthy contribution from Ken himself:

“Between the ages of 6, when I learnt to play and 23 (ed: 1951), when I ceased to be a student, chess had a relatively low priority among various time-competing interests and activities, so I never got around to studying theory. Things changed when I became a civil servant and needed a replacement for philosophy as an intellectually absorbing subject which could be argued about with friends over beers, and for the next 12 years chess became my main interest.

Since 1964 I have been working for the OECD in Paris, where my friends are not chess enthusiasts and, although chess remains a major pleasure, my commitment to it has lessened. Nowadays, out-side correspondence chess, I play only occasional blitz games.

Coming late to serious chess has probably had at least some influence on my deficiencies and stylistic preferences. The deficiencies include an inability to visualize ahead with sufficient clarity to support accurate analysis, slow sight of the board which leads to silly errors through time trouble or failing stamina and less familiarity with theory than my better opponents. As to chess style, I have had to play romantically and subjectively to get good results.

If a game takes the form of a clear-cut position, where strategical objectives are clear and superior technique prevails, then mine generally does not. Consequently I have tended to play either sharp gambits or counter-gambits or to try to render the position sufficiently obscure for imagination and intuition to assume maximum importance. In keeping, my chess heroes have been Alekhine, Bronstein and Tal who revel in fantasy, however much Alekhine may claim that it is logically based.

When I took up competitive chess seriously in 1952, I made some progress and won a few minor tournaments, but in view of the defects already mentioned, it soon became clear that my potential for improvement was limited and that nearly all my games were aesthetically flawed. Fortunately, these defects represent no great handicap at correspondence chess, where I found myself pleased with a reasonable proportion of the game I played, and in addition, capable on the day (or more accurately over the years) of winning against almost anyone. Thus, against world champions I have two wins and one loss, (see below). I also have 80 per cent from five games against Russian grandmasters, even if a meagre 28 per cent from my eighteen games against all correspondence grandmasters. In 1954 when I began playing postal chess competitively, I did sufficiently well in a few British Postal tournaments to be accepted at a reasonably high level in the official international tournaments.

Not without luck (see Diagram l), I secured the 75 per cent necessary in two seven-player tournaments to qualify for the fourteen player preliminaries, the winner of which was to qualify for the following world championship. In the 1961-64 preliminaries, I played the best chess of my life, including valid opening innovations, imaginative pawn and piece sacrifices and even a technically efficient win in a queen and pawn end-game. I won the tournament with eleven wins, one draw and one loss, 1.5 points ahead of Maly of Czechoslovakia and two points ahead of Masseev, the Russian favourite, thereby obtaining my first norm towards the International Master title. My first annotated game is the win against Maly (ed: to be inserted once we have tracked down the game score!) which was typical stylistically and also crucial, since if he had won it, he would have qualified for the World Championship instead of me: the second against Bartha of the United States is the most compulsive and difficult tactical game I have ever played, the last five moves alone requiring over 100 hours of analysis.

The quality of my chess in the 1965-68 World Championship was much inferior. The tournament began disastrously. I went in for three losing variations as Black and made a suicidal clerical error in the opening so that after 3 months I had four losses from four games. Later, there were compensations. I won against V. Zagarovsky, the reigning world champion (the third annotated game) and obtained just (but only just) the necessary 33.3% per cent to obtain the correspondence chess international master title. For this I needed a win and draw from my last two games which

after 3.5 years, had to be adjudicated.

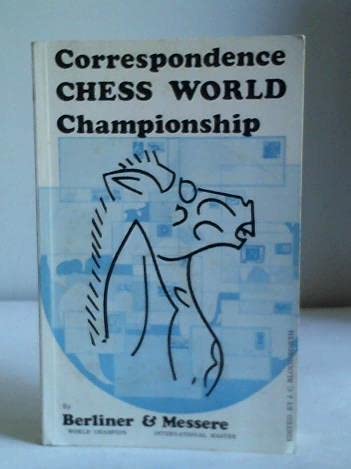

Fortunately, the win and draw were relatively clear, though this would not have been so a few moves earlier. An an illustration of how the threat of adjudication breeds irrationality, Diagram II gives the closing stages of my win against J.Estrin of the USSR – a more recent correspondence chess world champion. My only other game against a world champion was against the winner of this tournament, Hans Berliner of the United States, with whom I collaborated on a book of the tournament. The collaboration was stimulating but not without friction, since I had to write 75 per cent of the book to see it ever finished. It took a year to complete, 3 years to appear (published by BCM) but in the end was well-reviewed, sold over 2000 copies and royalties are still (gently) drifting in.

In the early seventies, in order to reduce numbers of games, I retreated altogether from individual tournaments, just playing twice for England in the Olympiads. Whether team play did not suit my style, or whether my technique had improved but imagination withered, I drew nine of my seventeen games from the two tournaments, winning four and losing four. As England looked likely to aspire to medals for the first time ever, my 50 per cent would not help matters and I gladly retreated to first reserve, which to my dismay required taking over five unfinished games of Hugh Alexander, who died during the tournament, and who, for me, has always been England’s most attractive player and writer. My most uncomfortable decision in correspondence chess was a rejection of Hugh’s intended continuation in one of these games, {Diagram III). Of these five games, I lost one and drew four and England won a bronze medal.

In 1974 was invited to compete in the Potter Memorial Tournament of four postal grandmasters and nine international masters. After so many years of responsible’ team chess for England, I went beserk and sacrificed a pawn in ten of the twelve games, trying later to salvage inferior end-games. Result 33 % per cent. B. H. Wood invited me to write a book of the tournament, to which a number of the players contributed and this was published in 1979.

Also in 1979 I began to play in another invitation tournament of thirteen players organised by the Australian Correspondence Chess League, which became a memorial to CJS Purdy, its president and the first world postal champion, who died soon after the tournament began. At the time of writing, this tournament, comprising four grandmasters (including one former world champion and two runners-up) and eight international masters, is still in its early stages.”

From British Chess Magazine, Volume CXXV (125, 2005), Number 5 (May), page 226 we have this obituary:

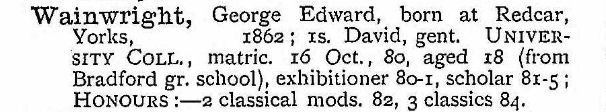

“Kenneth Charles Messere (16 iv 1928, Richmond – 31 iii 2005, Paris) was one of Britain’s strongest correspondence players (he held the correspondence IM title) and well-known author of books on the subject. After graduating from Oxford University, Ken Messere went to HM Customs and Excise, and thence to the Organisation for Economic Development (OECD) where he became head of the fiscal affairs division and a world expert on fiscal law. He reached the final of 1965-8 world correspondence championship, beating world champions Zagorovsky and Estrin, and wrote the book of the tournament with Hans Berliner (published by BCM)”

From The Potter Memorial by Ken Messere, CHESS (Sutton Coldfield), “Chess for Modern Times” Series, 1975 we have this potted biography:

“Compiler of this book, took 3rd place in 1957 and 2nd in 1968 in the championship of the Postal Chess Club. Scores of 4.5 out of 6 in the ICCF Masters 1957-8 and 4/6 in the 1959-61 Championship took him to victory with 11/5 out of 13 in the 1961-3 semi-finals, securing him his first international master norm and qualifying him for the 5th World Championship 1964-7 in which he scored 5.5, just enough for the IM title, with wins over Zagorovsky, then world champion and Estrin, world champion now. Ken Messere collaborated with Berliner, who won it, in a book on the tournament.

He then switched to play exclusively as a member of the British Olympiad team, taking over 2nd board when Alexander died.

The switch back from rather cautious team play to enterprising individual games in 1974-7 provides some of the subject matter of this book.”