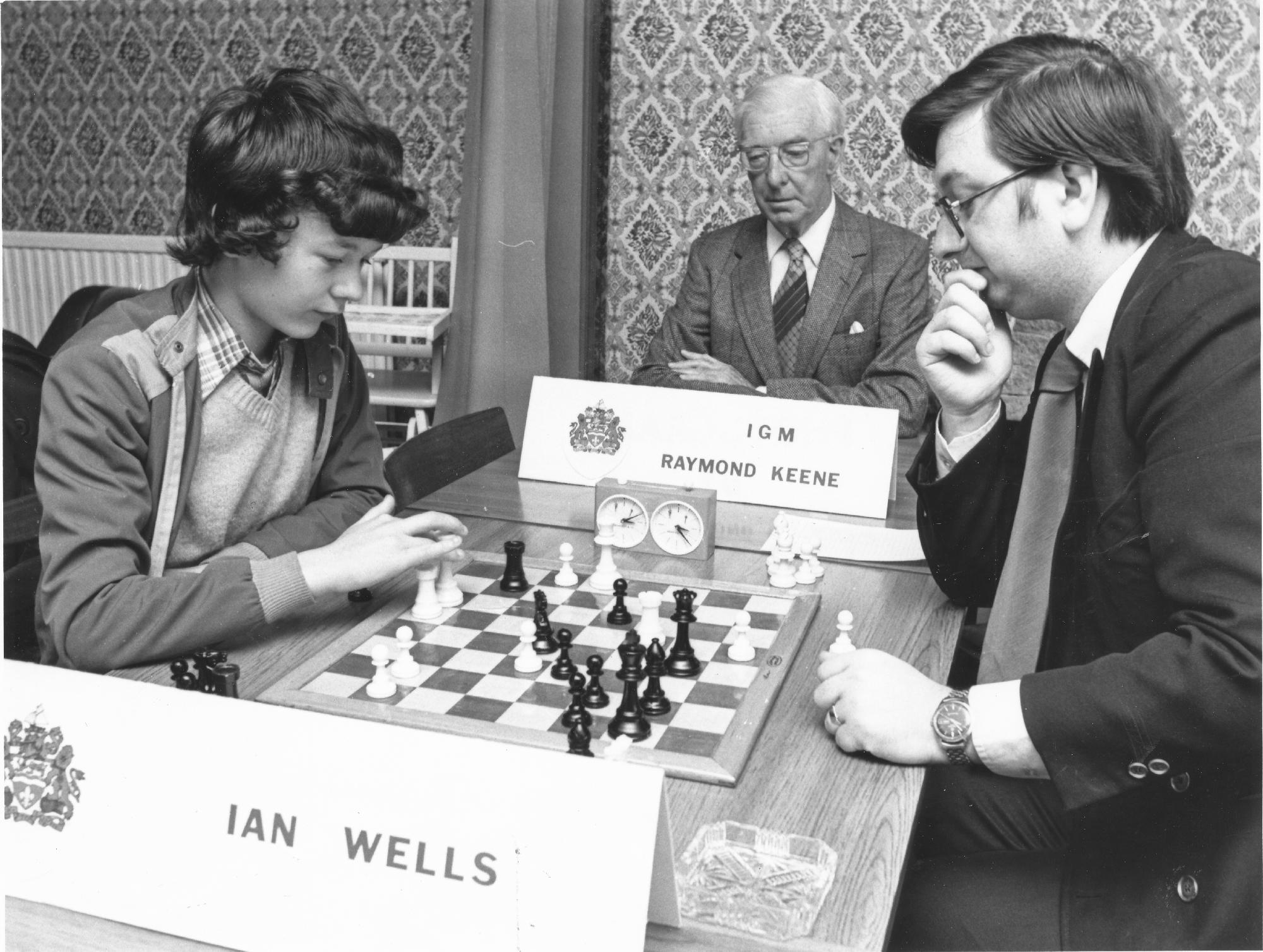

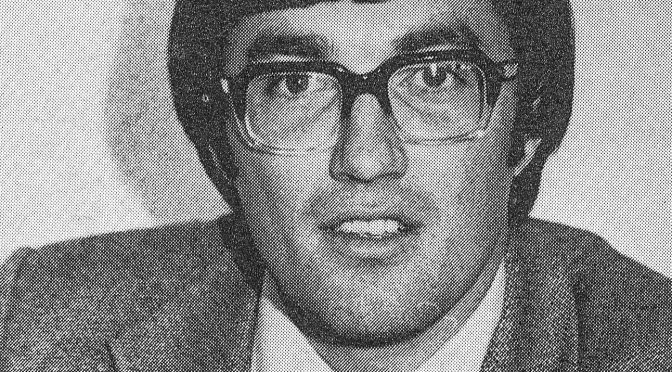

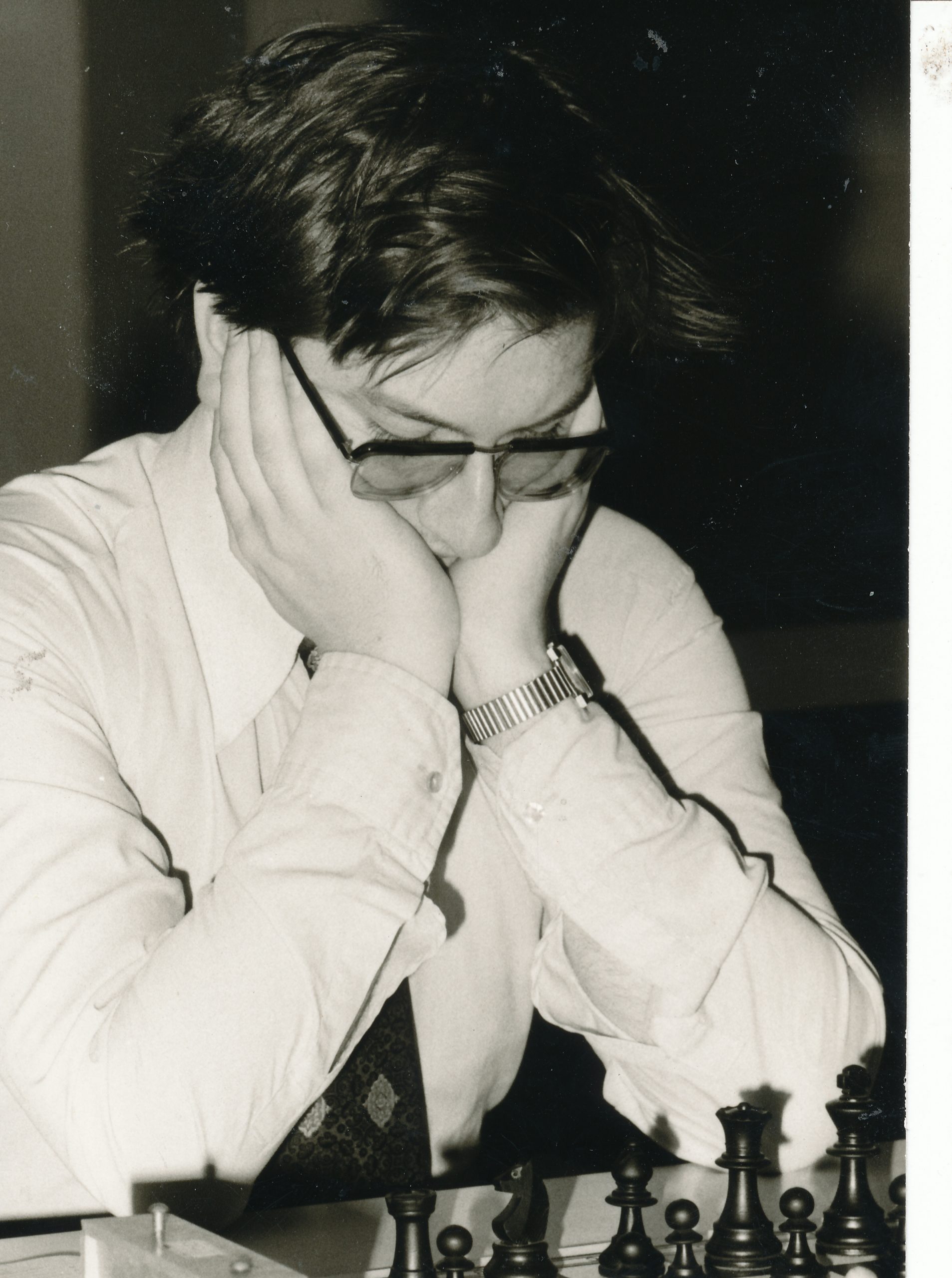

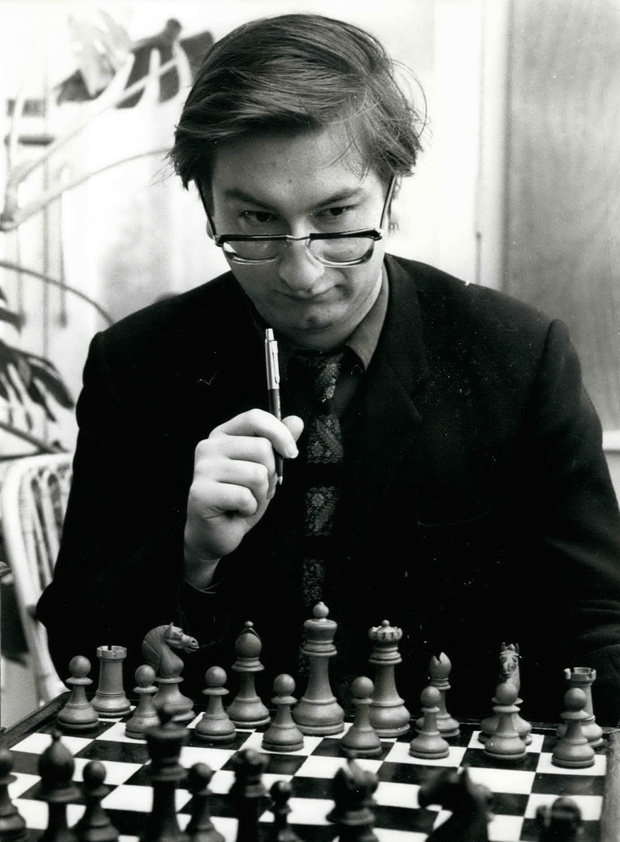

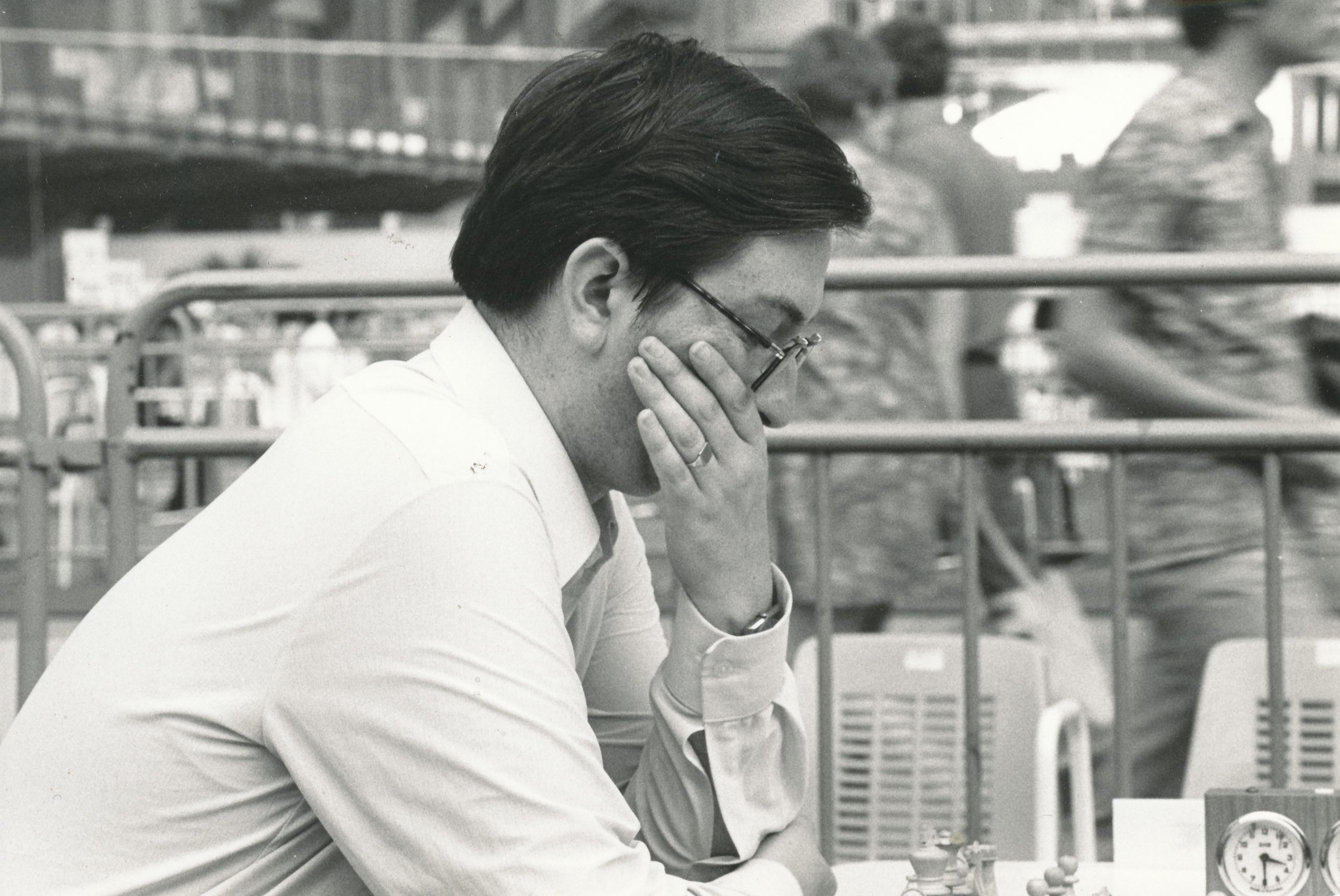

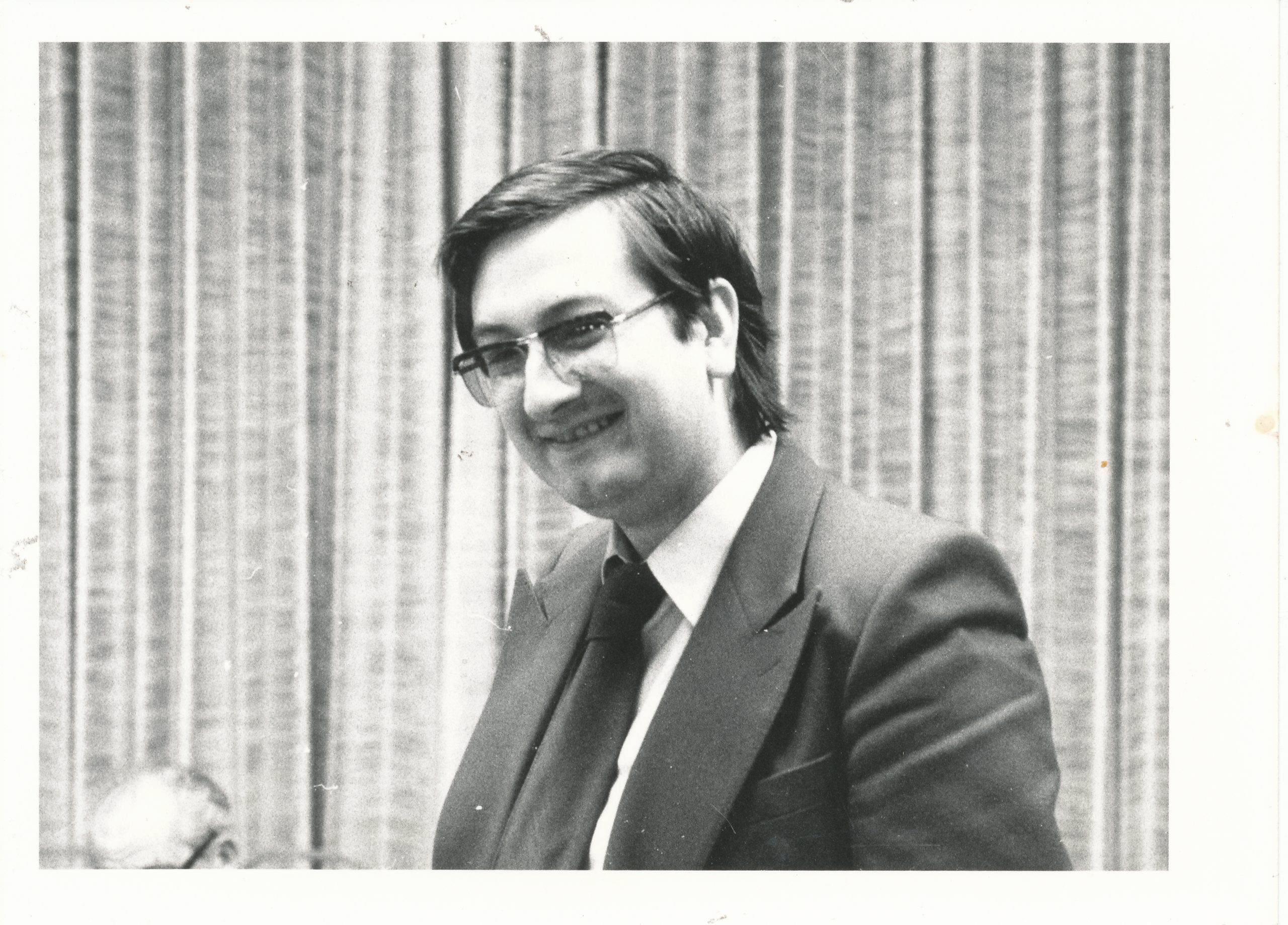

We send birthday wishes to GM Raymond Keene OBE.

Raymond Dennis Keene was born on Thursday, January 29th 1948 in Wandsworth, London to Dennis Arthur and Doris Anita Keene (née Leat). Dennis and Doris were married in 1943 in Camberwell. Doris was born on May 27th, 1921 in Lambeth and was a shorthand and invoice typist.

Dennis and Doris also had a daughter Jackie Keene who later married chess historian, RG Eales. Jackie is Emeritus Professor at The University of Kent in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities. Jackie played in the Glorney Cup.

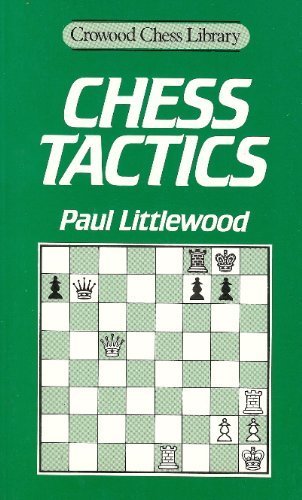

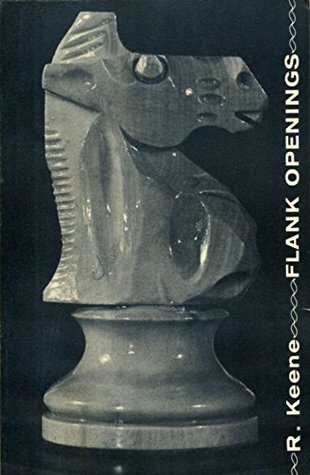

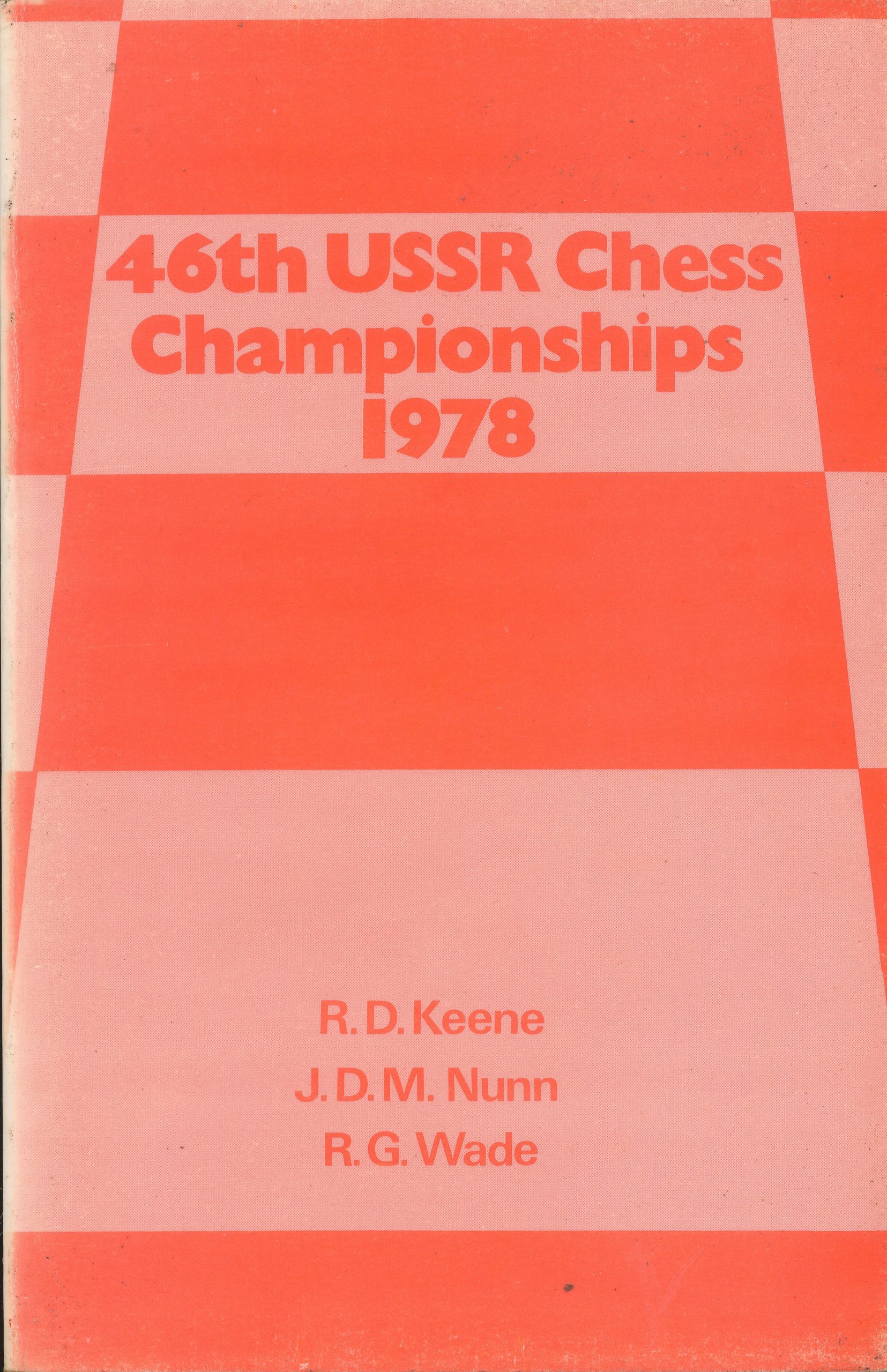

Ray was educated at Dulwich College between 1959 and 1966 thereby becoming an Old Alleynian. In 1967 Ray went up to Trinity College, Cambridge to study Modern Languages specialising in German and graduating with an MA. Amongst their Alumni are five spies including Blunt, Burgess and Philby. During the gap between Dulwich College and Cambridge Ray (aged 18) wrote his first (and one of his best) book : Flank Openings :

Being published at the age of 19 this must be close to the earliest age an English player has had a chess book published that was not ghost written. (Leave a comment if you know differently!)

Following this legendary tome Ray collaborated with Leonard Barden and Bill Hartston on The King’s Indian Defence from BT Batsford Ltd:

and in 1972 we have

followed in 1973 by

All of which were favourably received helping Batsford to establish a strong reputation.

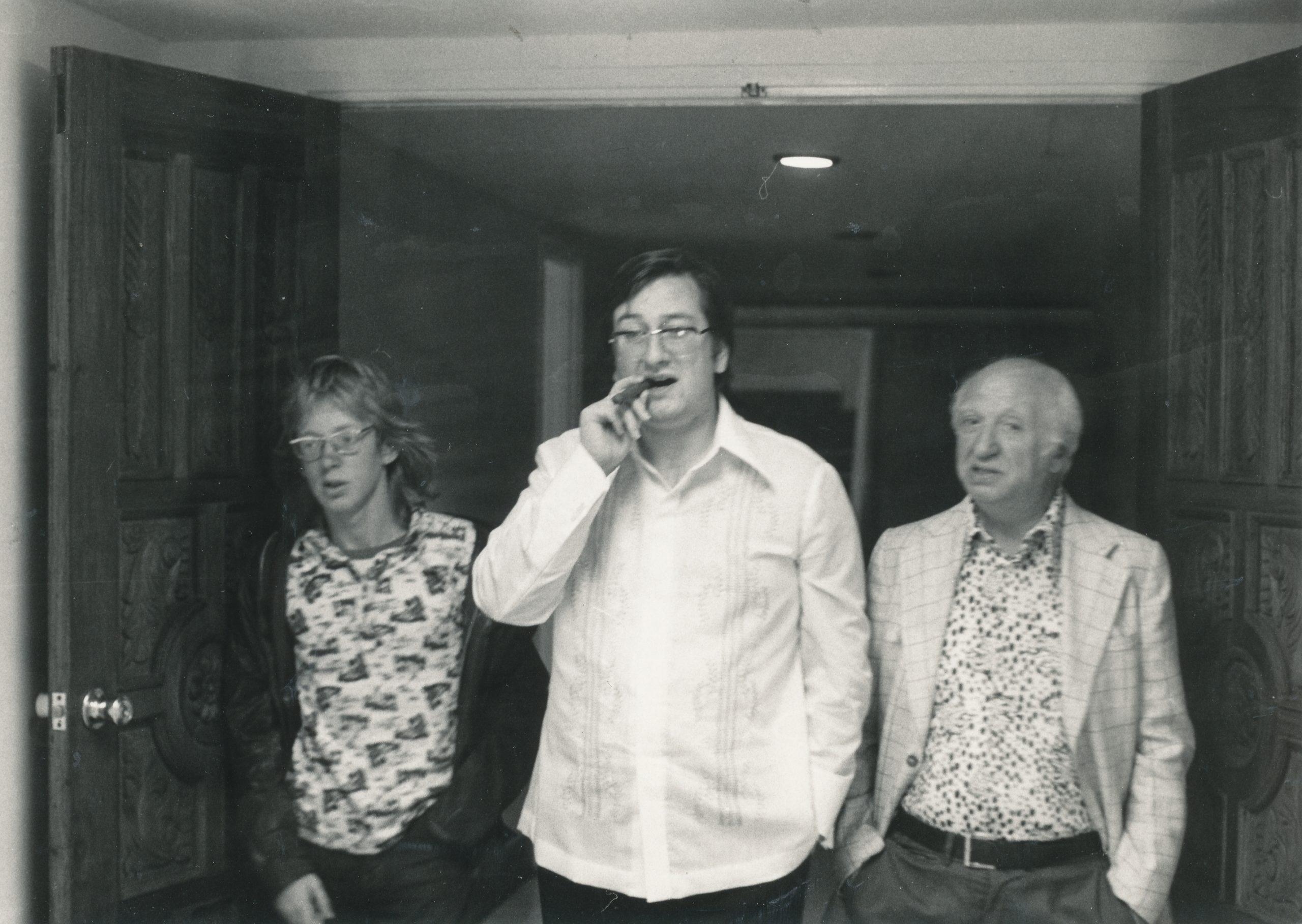

In July 1974 Ray married ex-ballerina (and now Dance Teacher) Annette Sara Goodman in Brighton, East Sussex. Annette became a director of World Memory Championships International Limited on January 17th 2008 and resigned on April 9th 2008. They have one son, Alexander Phillip Simon Keene, born in 1991. Godfather to Alexander is Scottish International, IM David Levy.

Annette is the sister of IM David Simon Charles Goodman who now resides in New York.

Also in 1974 George Bell & Sons published Ray’s most acclaimed work (and arguably his best) : Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal

Alexander is currently the Company Secretary of the aforementioned company, Julian (a retired teacher from Brighton) is another active director.

In 1985 Ray became the sixth British chess player to be awarded the OBE when it was awarded in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List. The citation read “For Services to Chess”.

According to Companies House Ray has held a total of 30 directorships in various companies such as :

- Brain Plan 2020

- World Mind Mapping Championships

- World Speed Reading Championships

- Buzan International Technology

- Buzan World

- The World is My Oyster

- World Memory Championships

- Intelligent Resources and Services

- Outside in Pathways

- UK Primary Schools Memory Championships

- UK Schools Memory Championships

- The School Memory Championships

- The Schools Memory Championship

- Mental Literacy for All

- Festival of the Mind

- Festival of the Mind International

- The Brain Trust

- Impala (London)

- Tony Buzan International

- World Memory Championships International

- World Peace and Prosperity Foundation

- Zeticula

- Mind Masters Management

- Intellectual Leisure

- Brain Sports Olympiad

- Mind Sports Promotions

(Our particular favourite has to be the unpretentiously entitled “World Peace and Prosperity Foundation” although “The World is My Oyster” runs it a close second.)

Ray, Annette and Julian Simpole currently live in Clapham Common North Side, London, England.

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by David Hooper and Ken Whyld :

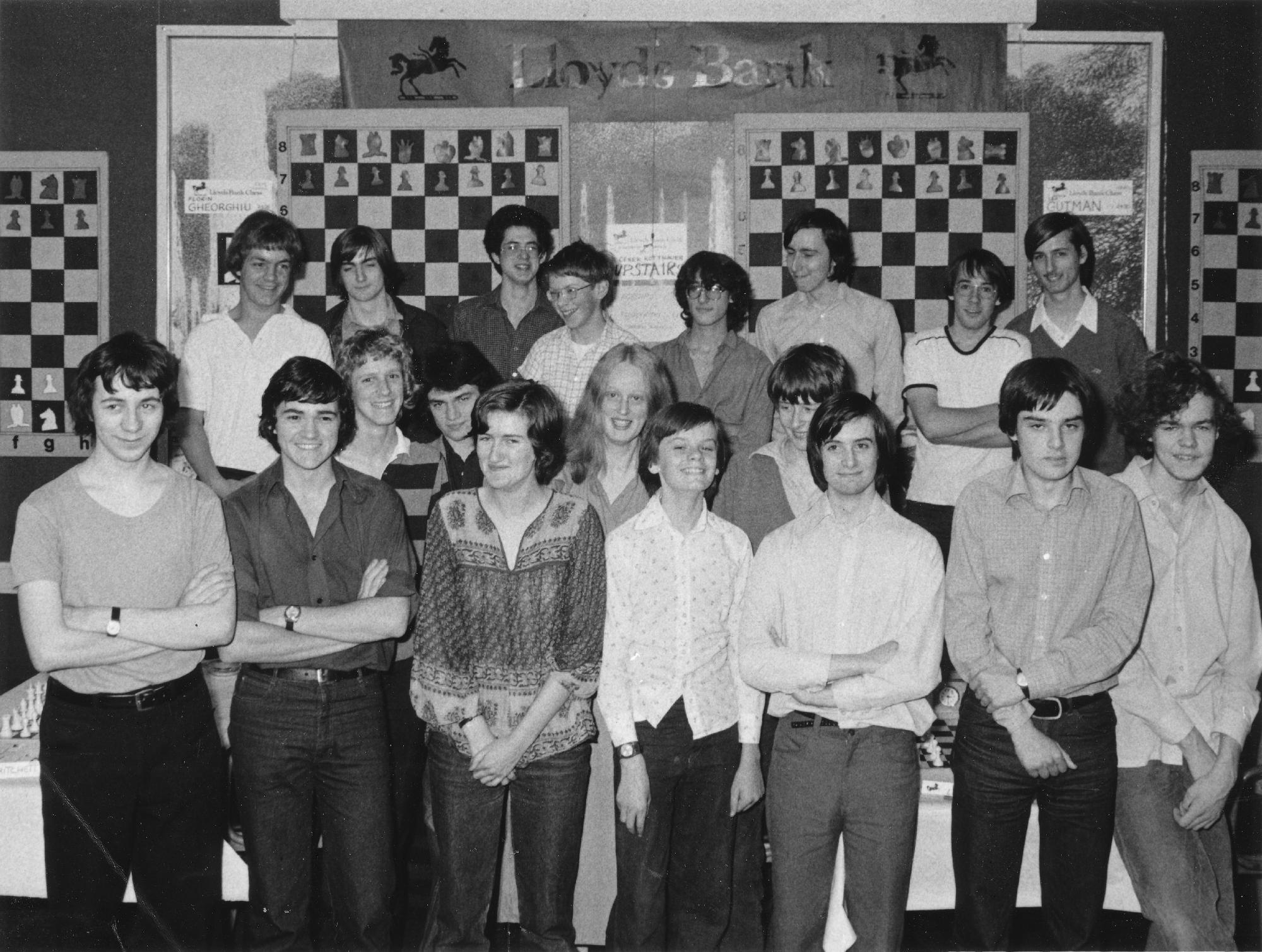

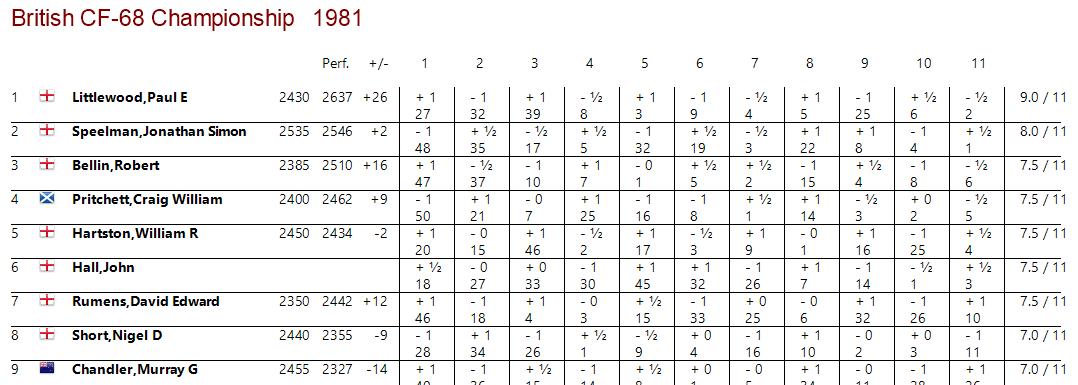

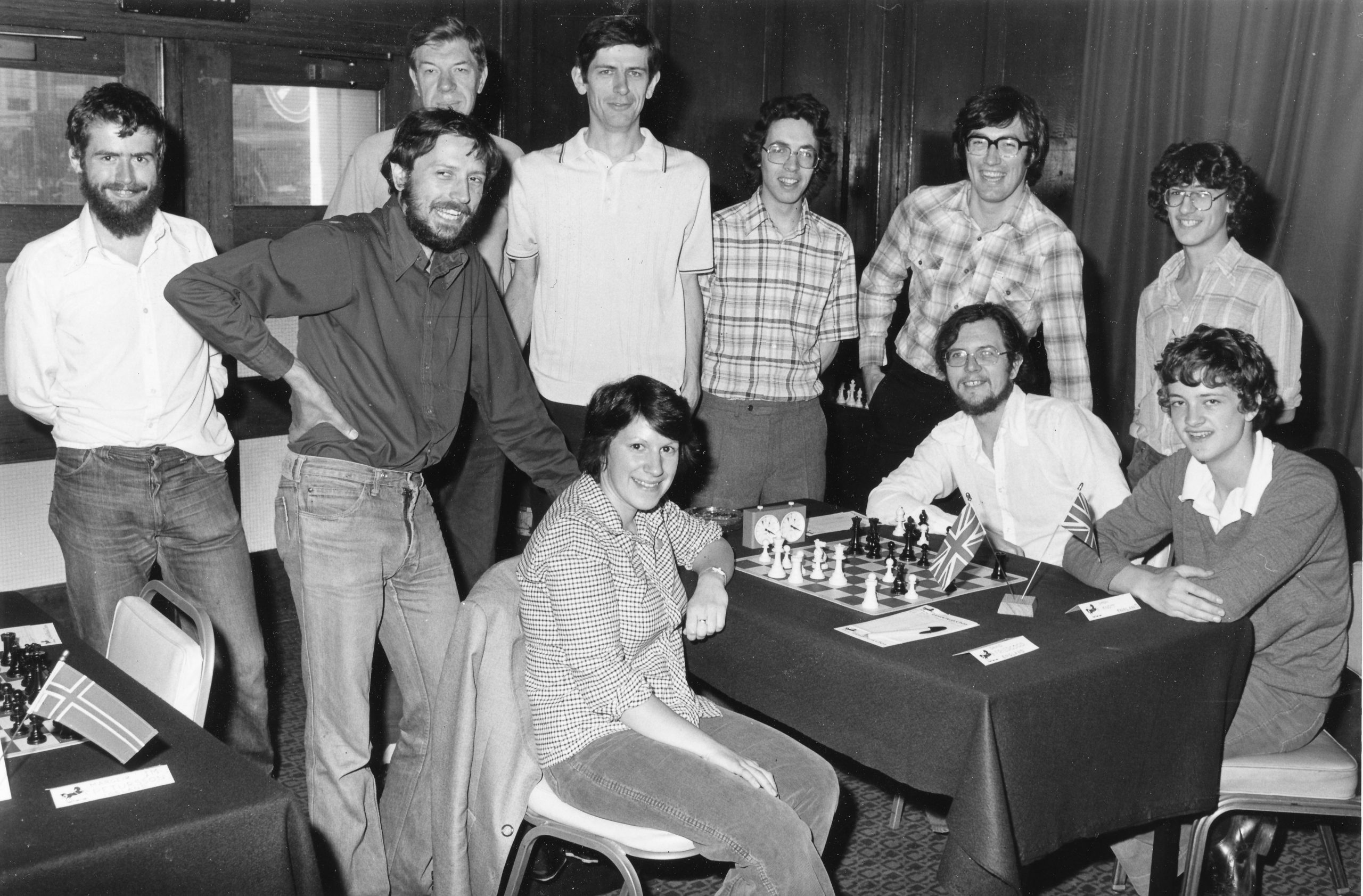

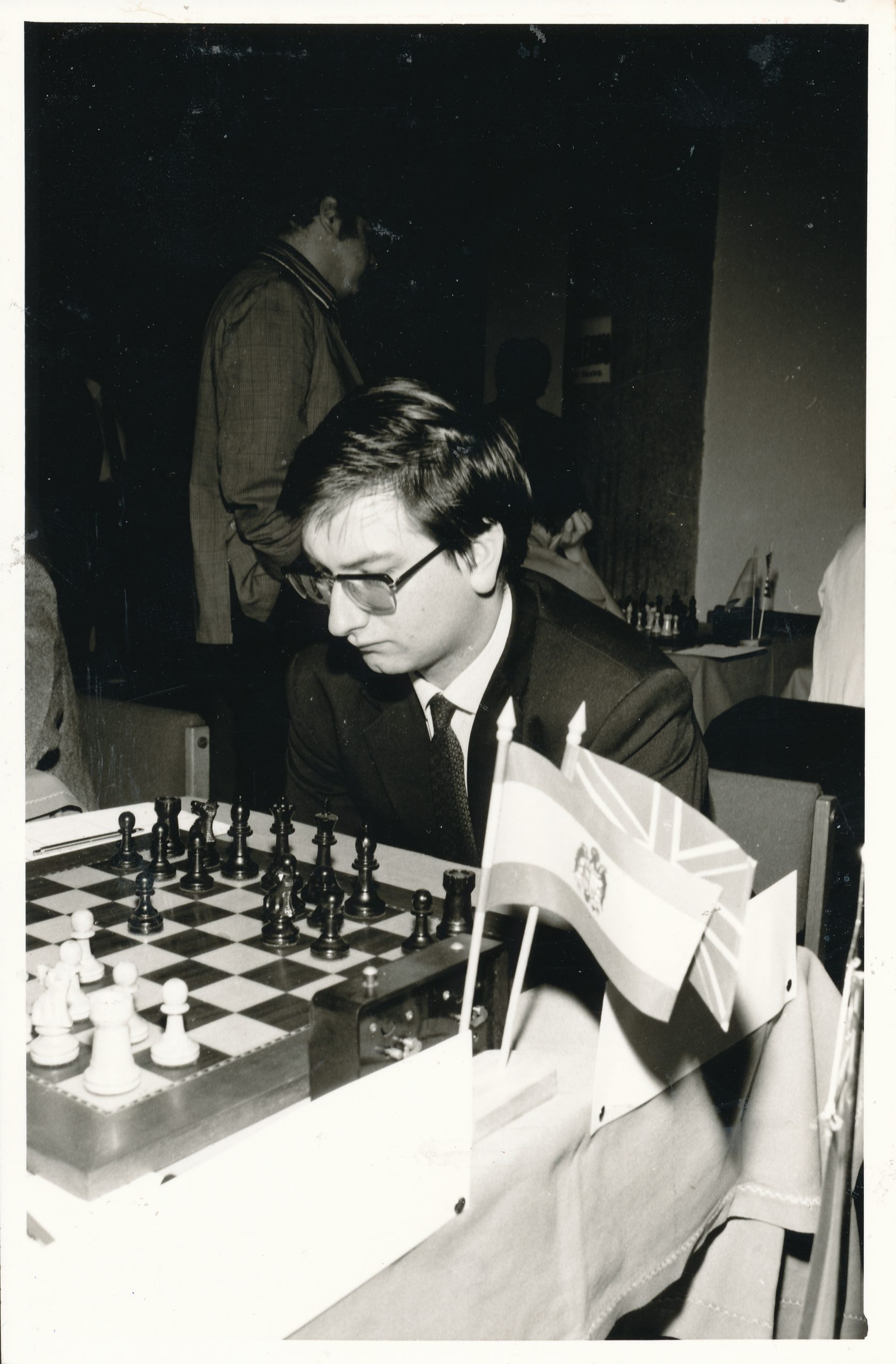

English player and author, British champion 1971, From 1966 he played in several Olympiads and his performance in two of them, Nice 1974 ( + 7=6-2) and Haifa 1976 (+4=6), gained him the title of International Grandmaster (1976). His best tournament win was at Dortmund 1980 (category 8), He studied the games and teaching of Staunton and Nimzowitsch and revealed with unusual insight the strategy of the former and the stratagems of the latter in two books: Staunton : the English World Champion (1975) and Nimzowitsch: a Reappraisal (1974). He also wrote Flank Openings (3rd edn, 1979); these openings are the ones which he prefers to play, which he knows best, and which suit his solid positional style.

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks :

International Master (1972), British Champion in 1971 and a regular member of the British team since 1966 playing on top board on a number of occasions.

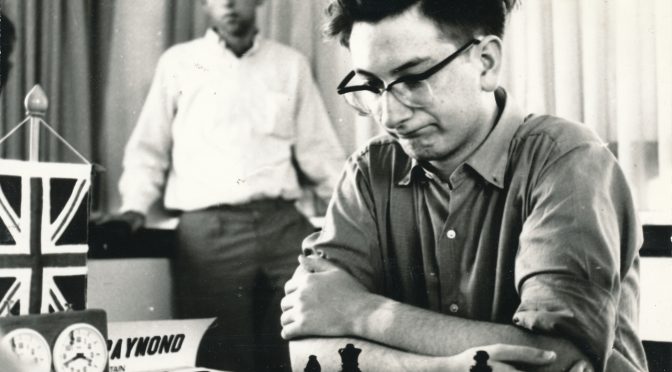

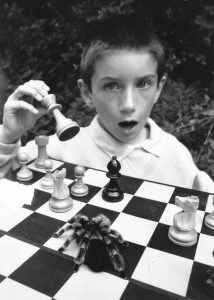

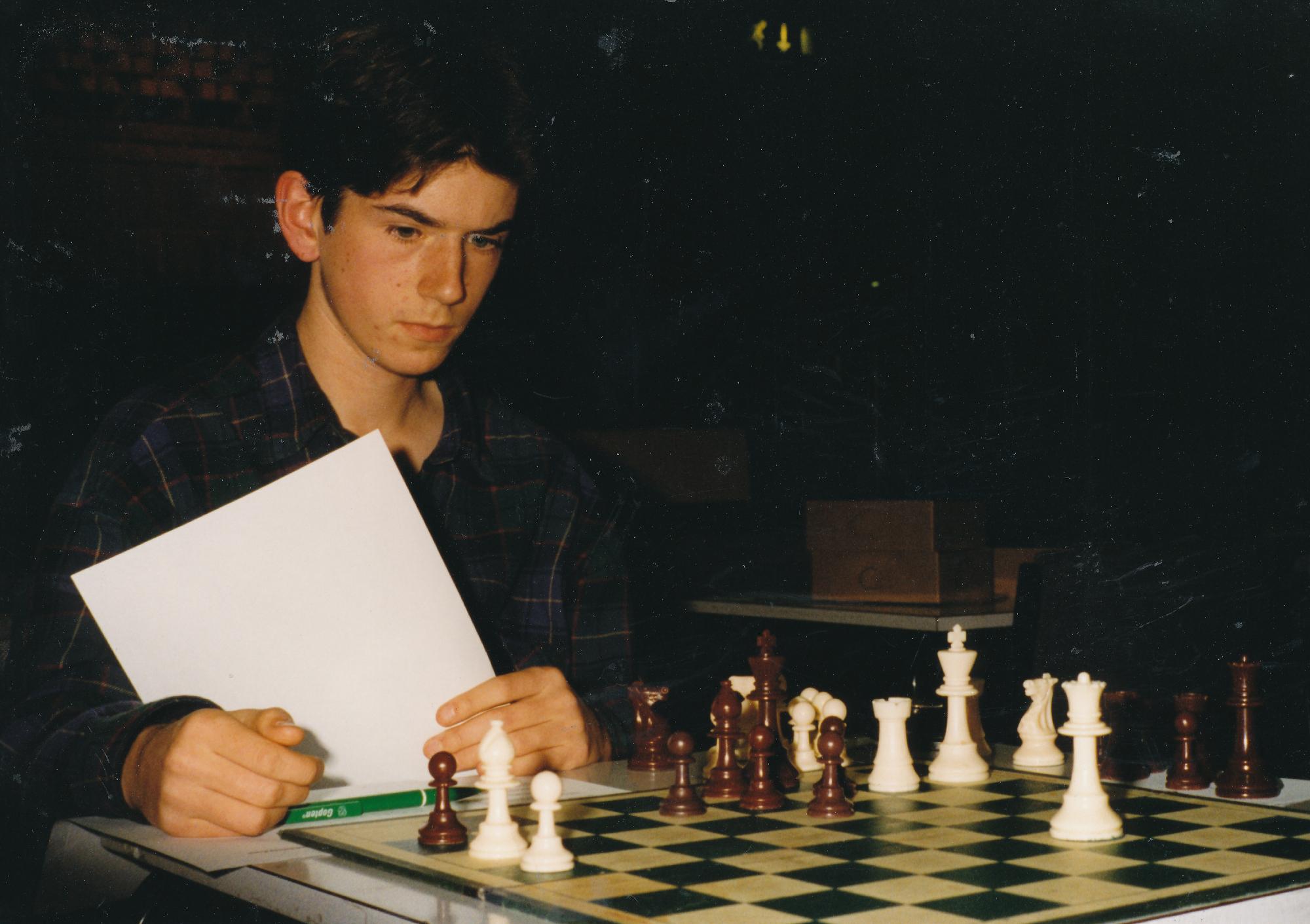

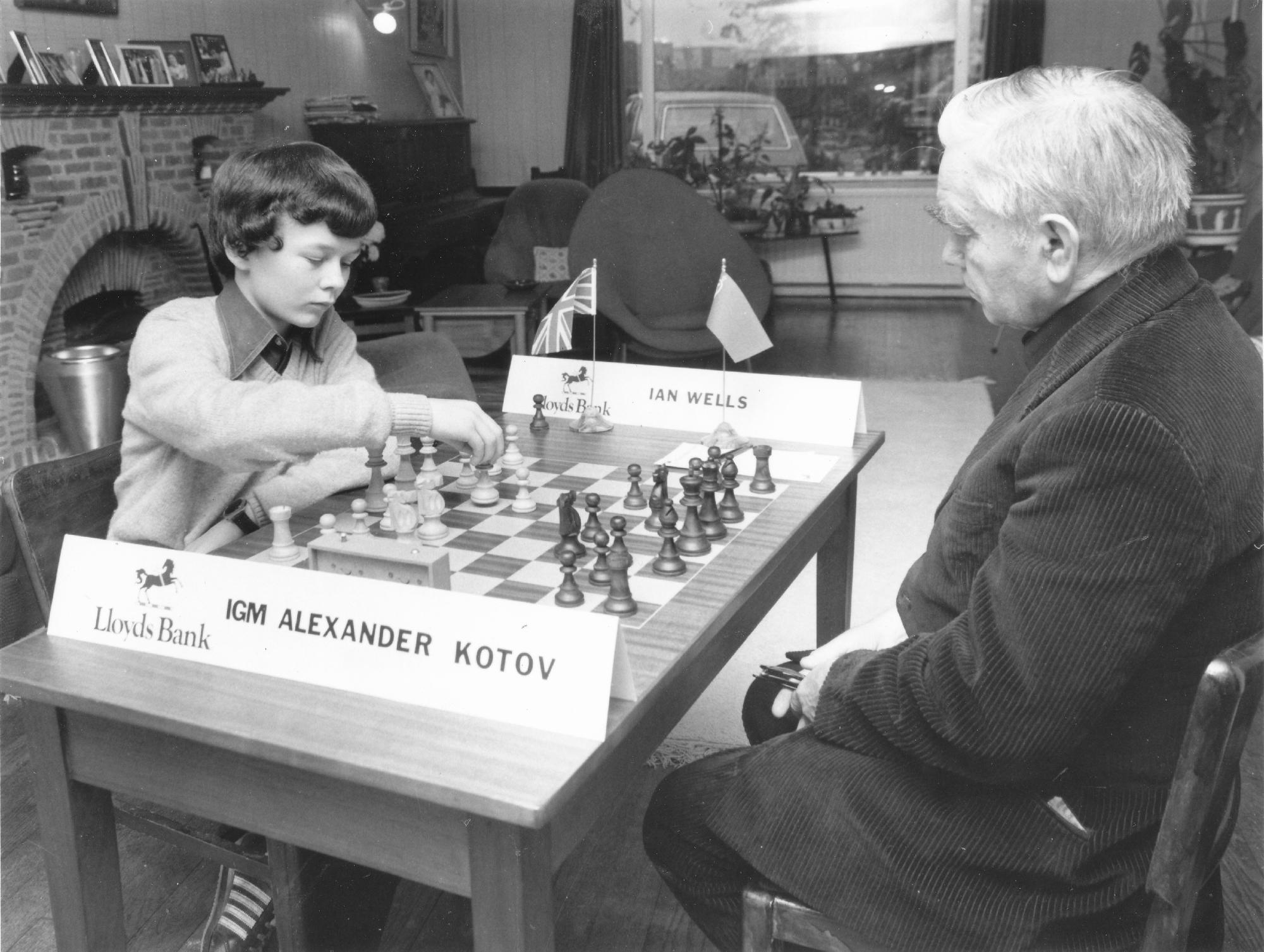

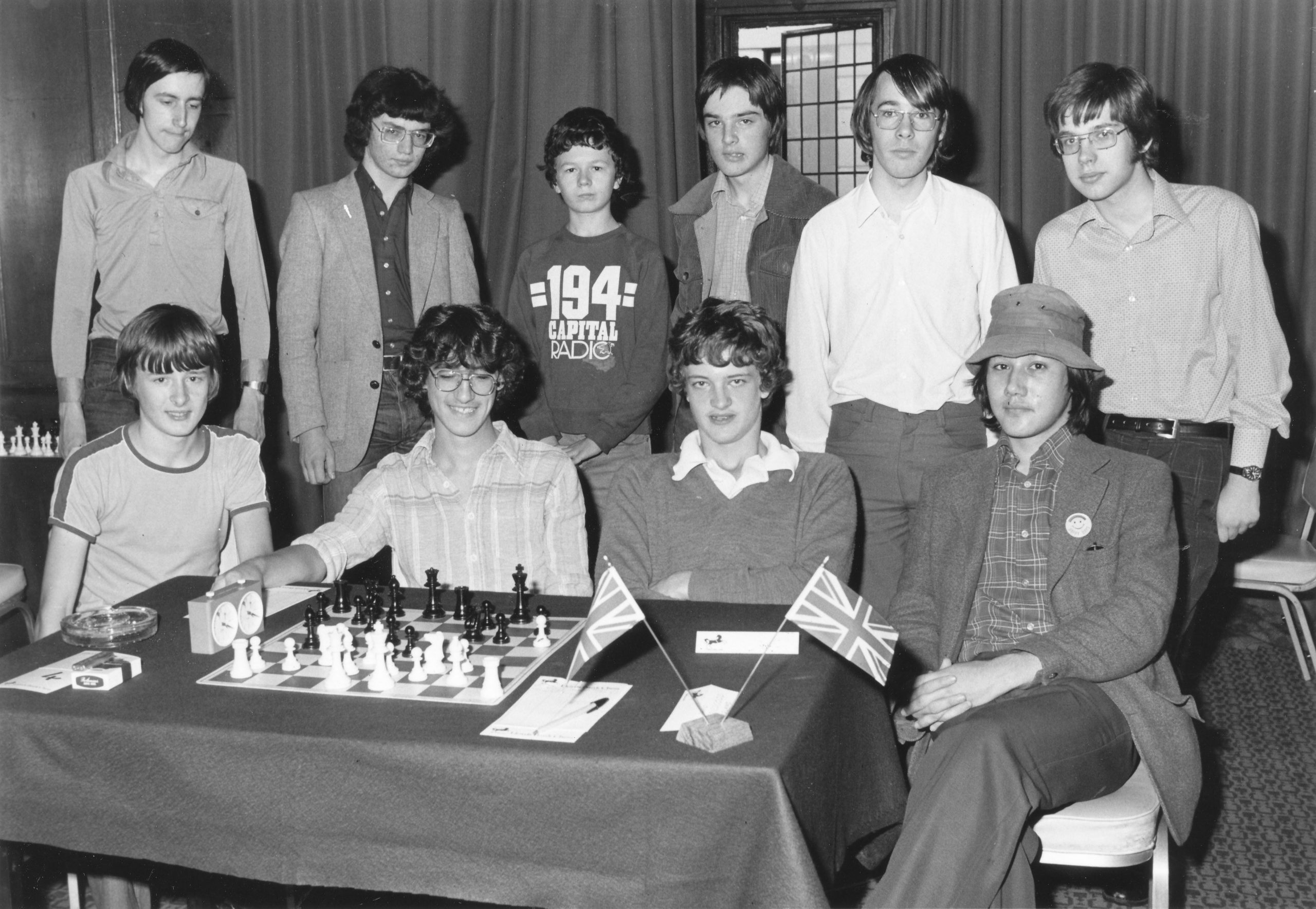

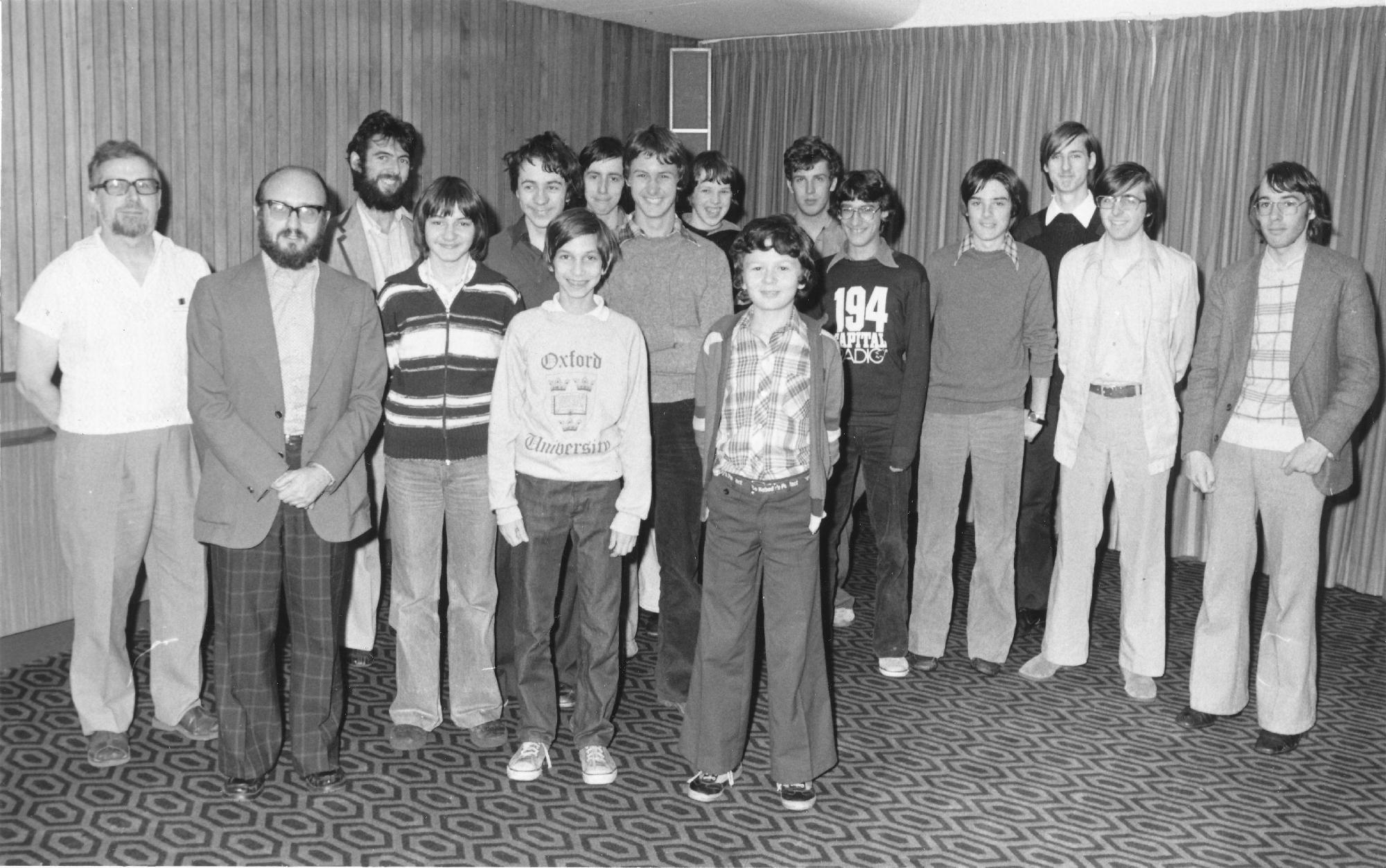

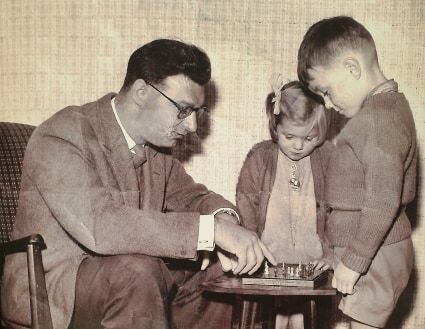

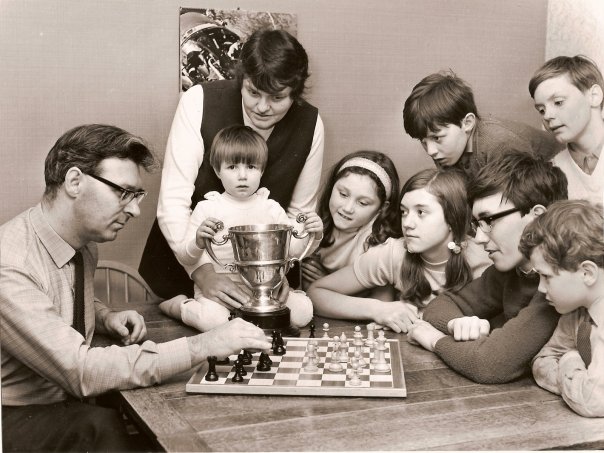

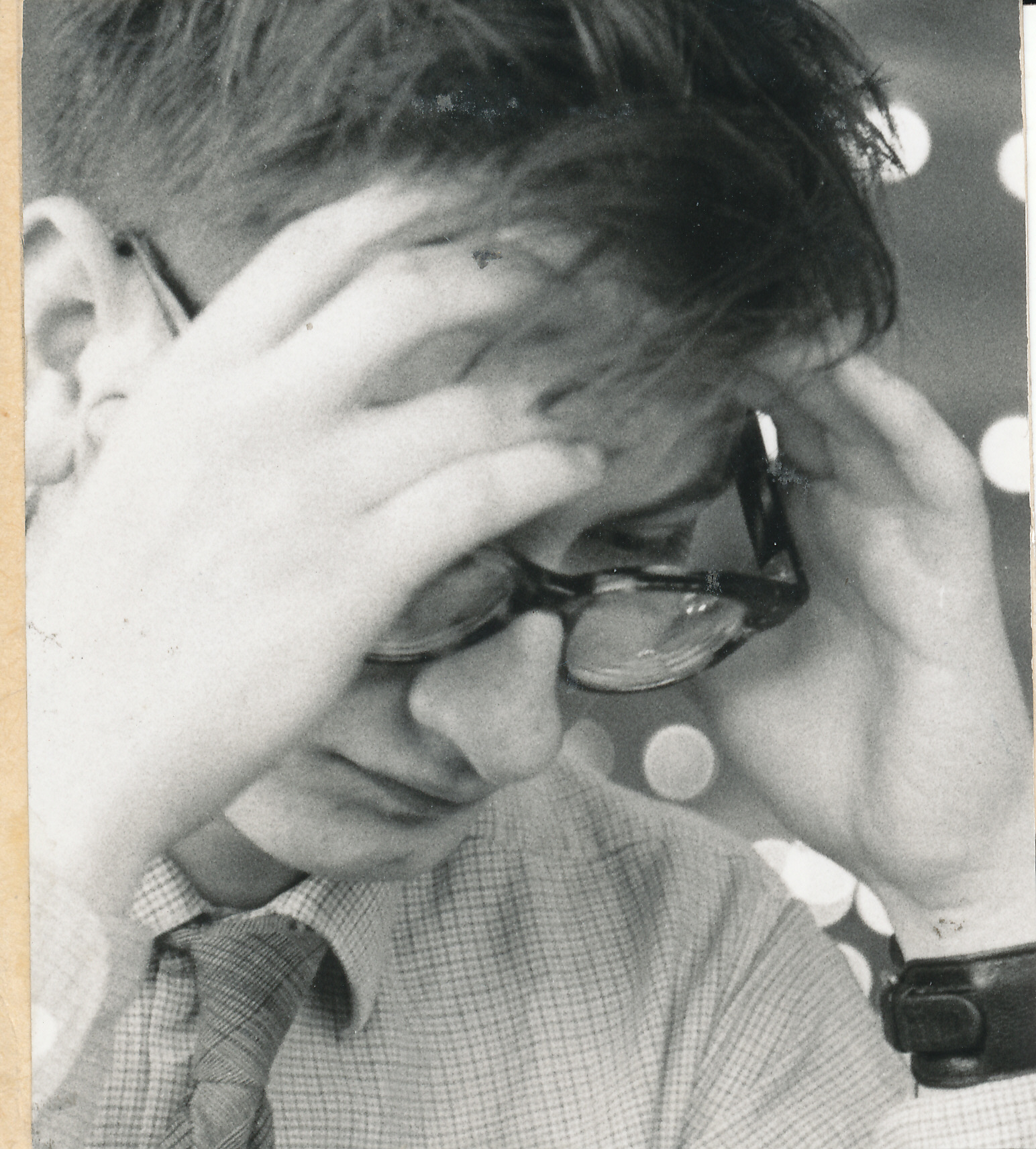

Raymond Keene was born on 29th January 1948 in London and learned to play chess at the age of six. He began to play seriously when he was thirteen. While at Dulwich College from 1959 -1966 he played top bard for the school team which won the Sunday Times National Schools’ Chess Tournament in 1965 and 1966.

In 1964, he won the London and British Boys’ Under 18 Championship (ed : In fact, the title was shared with Brian Denman) and the following year, at the age of seventeen, he became the youngest player to win the Surrey Championship. While at Cambridge he graduated in German Literature (B.A. Honours), he played top board for the university.

During his chess career, he has beaten both Botvinnik and Gligoric, In 1967, he came 2nd in the World Junior Championship and in 1968 he won the prize for the best score on board 4 in the Lugano Olympiad.

A difficult player to beat, Keene played in four British Championships without losing a game and also went through the Lugano and Siegen Olympiads unbeaten in 33 games.

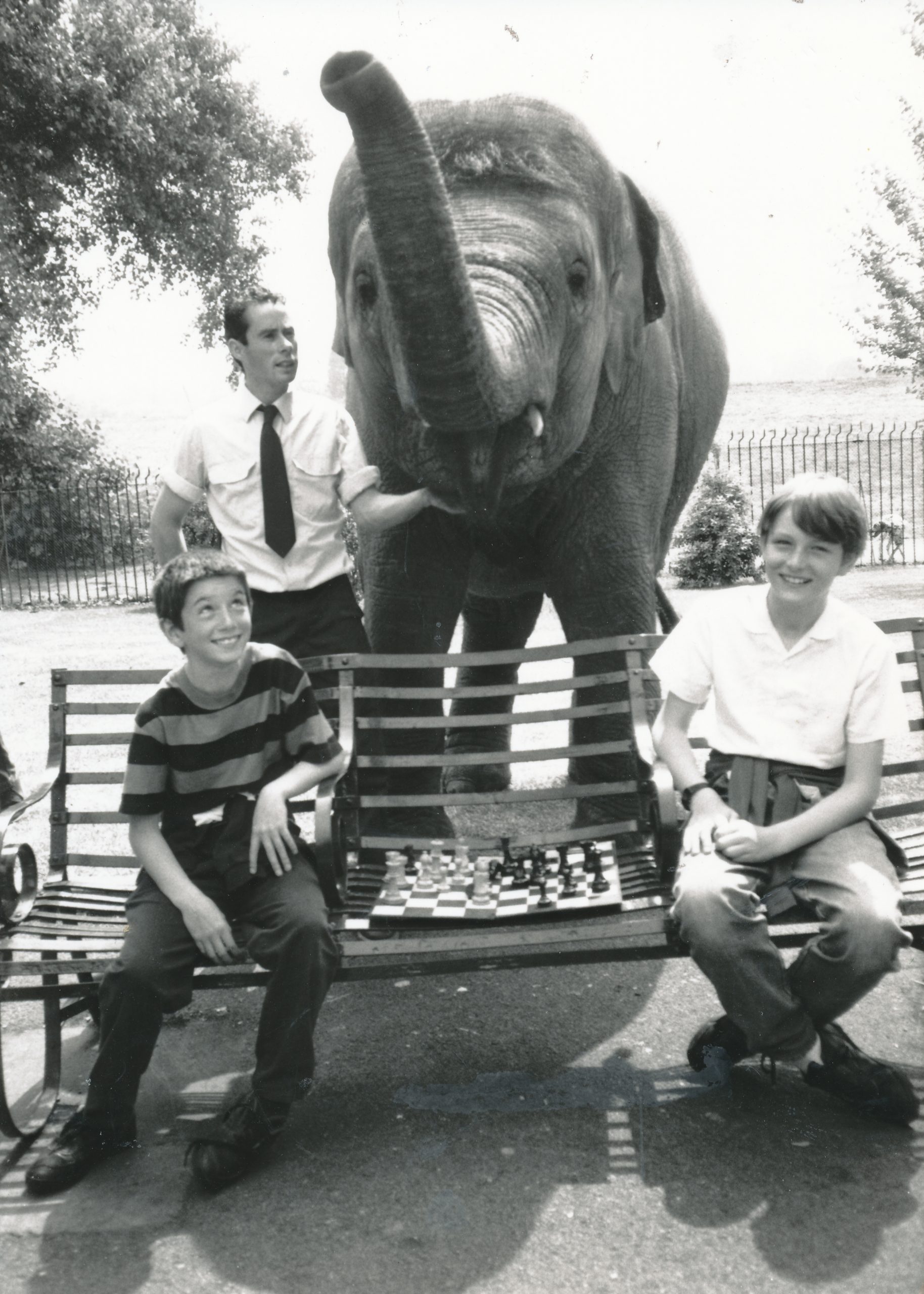

At Oxford in 1973, Keene set up what he believes is an English speed record for simultaneous chess, scoring 100 wins, 5 draws and 1 loss in 4.5 hours.

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

“British Grandmaster, British Champion 1971, Keene was born in London and was both London Boy Champion and British Junior Champion in 1964 (ed : In fact, the title was shared with Brian Denman).

Educated at Dulwich College and Trinity College, Cambridge, he soon became recognised, along with Hartston, as one of the two leading younger players in England. His style of play was different from that of his rival, being more complicated and less direct; but, like Hartston, he became a most formidable opening theorist with a vast knowledge of opening theory.

His first Olympiad was at Havana 1966 where he was the youngest member of the side and scored 65% on board six. In 1968 at Lugano he obtained 76.5% on board four and in 1970 at Siegen, playing on board two in the preliminaries and board one in the finals he score 68.8%.

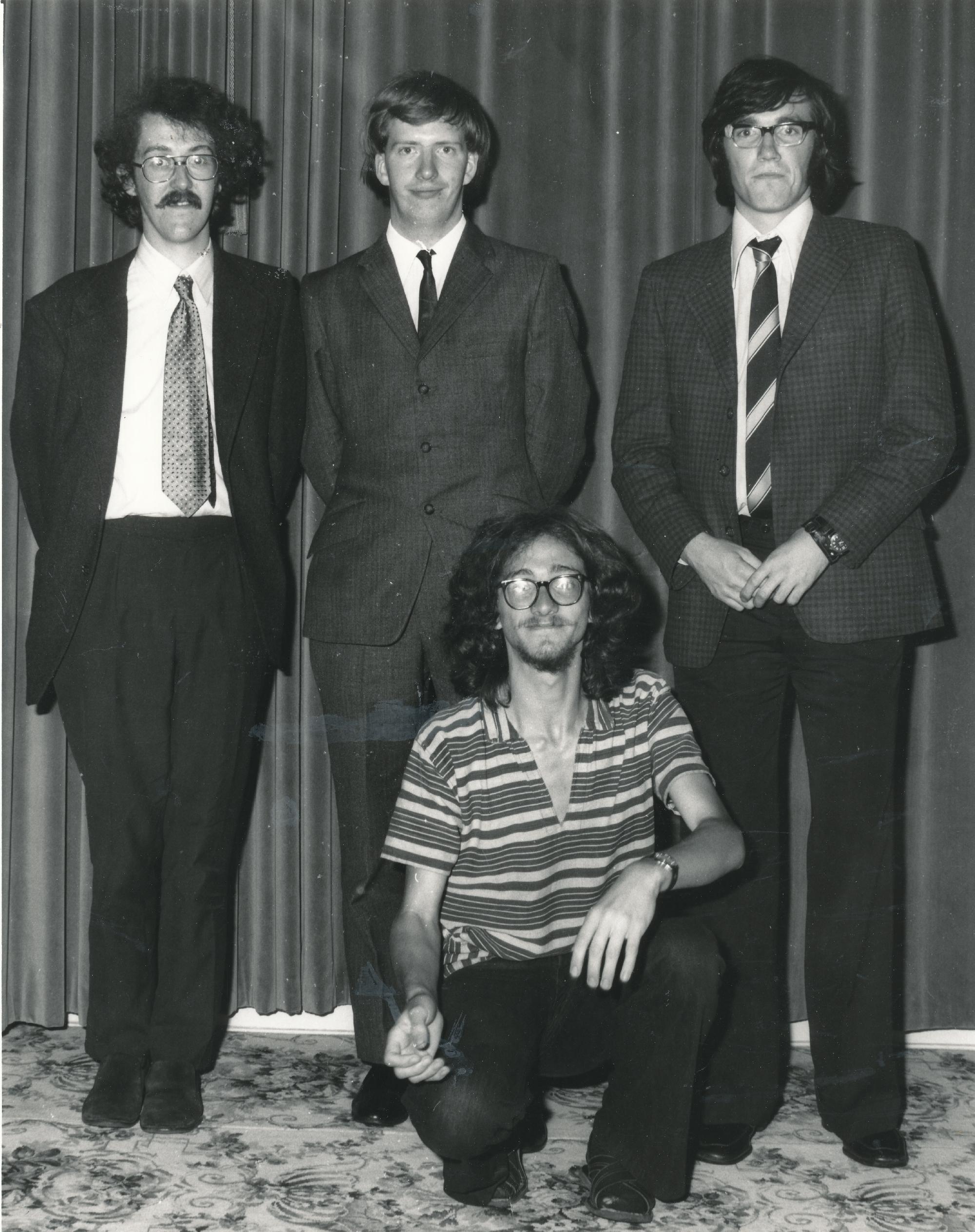

The year 1971 saw a double achievement, for in that year he won the British Championship at Blackpool and also secured the title of International Master.

Playing on top board in the 1972 Olympiad at Skopje, he scored 11.5 out of 20.

In 1974 he came 6th in a very strong Hastings tournament and then won first prize in the Capablanca Memorial Masters in Cuba. At the Nice Olympiad he scored 66.66% on 2nd board, attaining the first leg of the grandmaster norm. At Mannheim 1975 he was 3rd in the German Open championship and in that year he also came 2nd at Alicante. In 1976 he was 2nd at the Aarhus tournament in Denmark. He finished a most successful year in international chess by fulfilling the second grandmaster norm on 2nd board in the Haifa Olympiad, thereby becoming England’s second international grandmaster (after Tony Miles). (Harry Golombek)”

Ray was Southern Counties (SCCU) champion for the 1966-67 season.

Here is his extensive Wikipedia article

Noted historian Olimpu G Urcan writes on Alekhine versus Keene

and Edward Winter writes extensively about Ray’s journalistic activities

and finally, Keenipedia. A web site created by his many admirers…