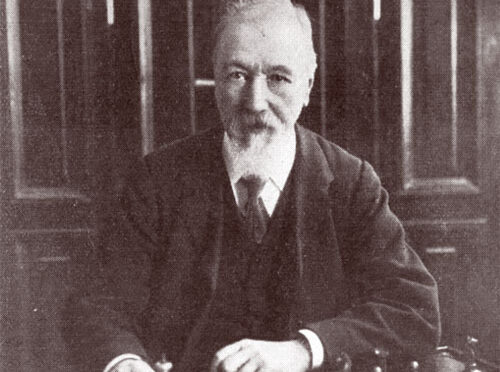

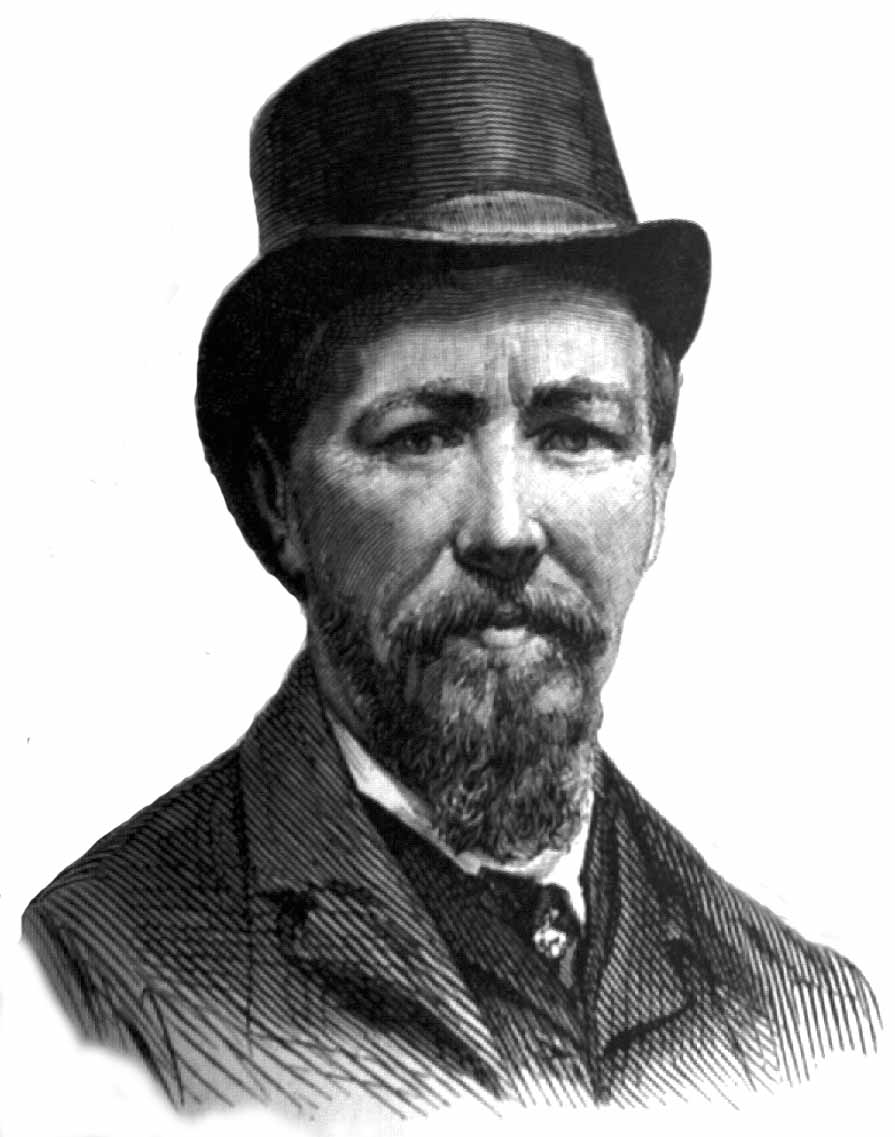

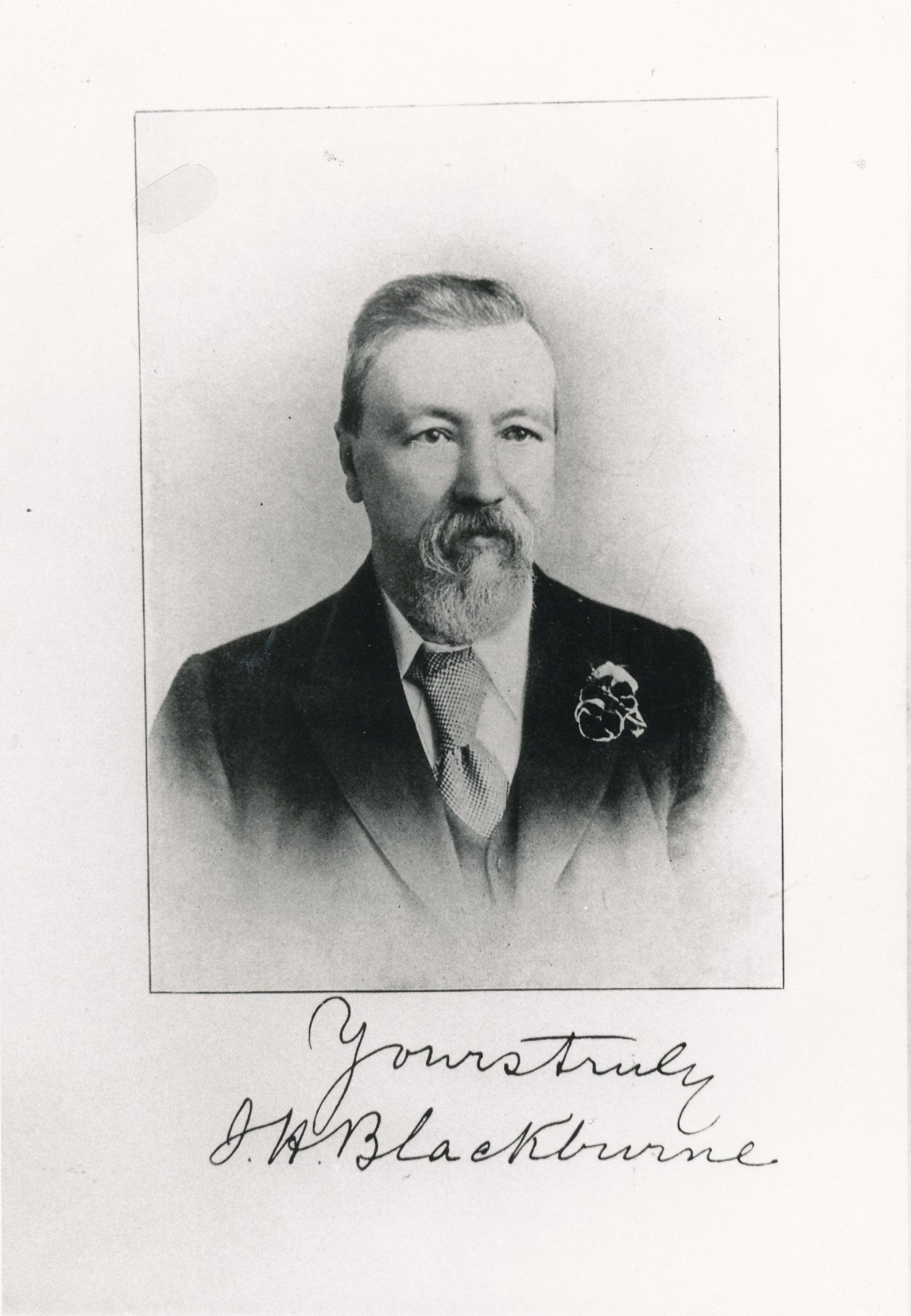

BCN remembers Joseph Blackburne (10-xii-1841 01-ix-1924)

The following (excerpts of) information were obtained via ancestry.co.uk / findmypast.co.uk:

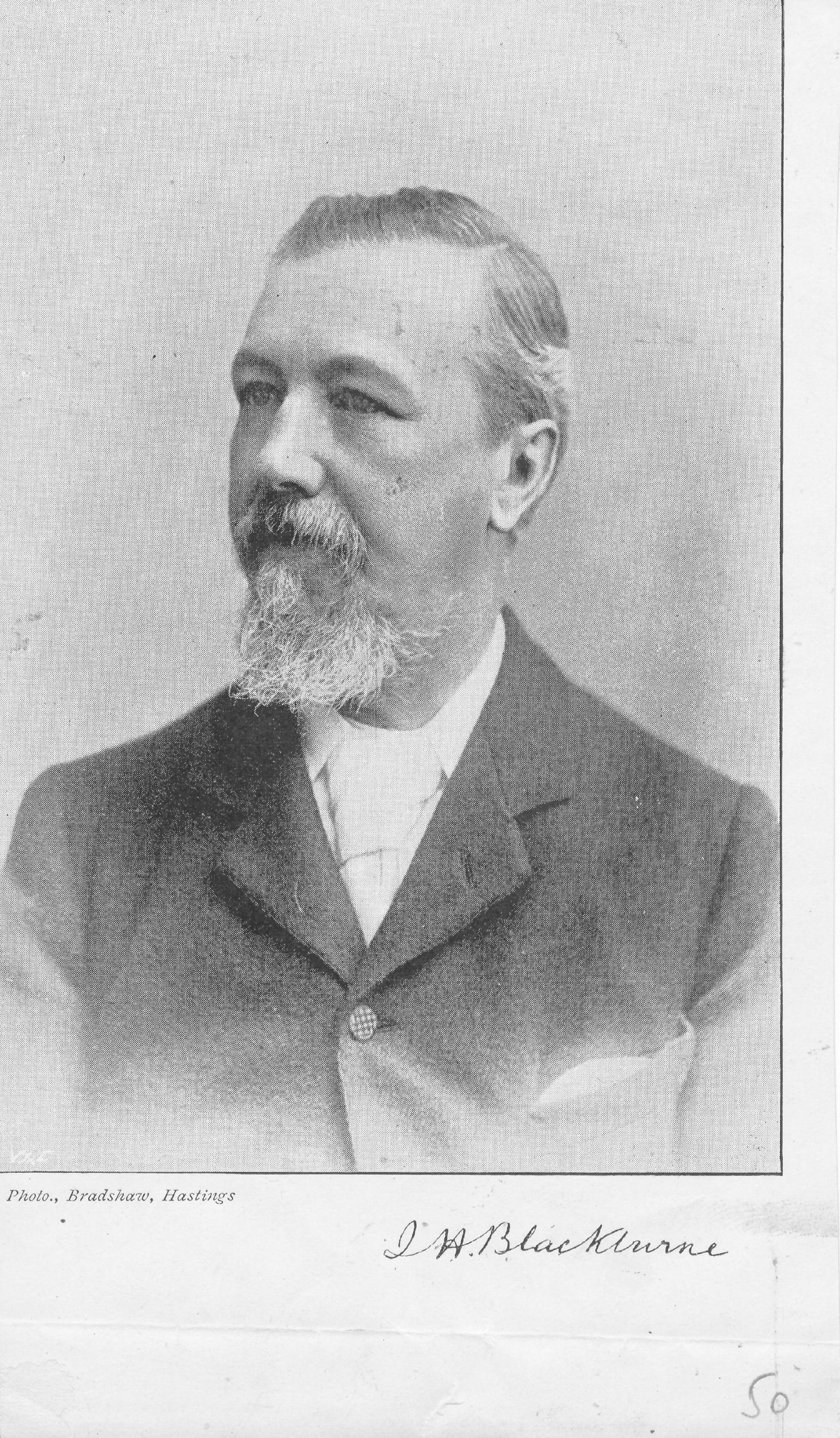

Joseph Henry Blackburne was born on Friday, December 10th, 1841 in Chorlton, Manchester. His father was Joseph Blackburn (aged 23, a temperance reformer) and his mother was Ann Pritchard (aged 24). He had eight sons and five daughters.

His brother Frederick Pritchard Blackburn died on 11 October 1847 in Lancashire, Lancashire, when Joseph Henry was 5 years old.

His sister Clara was born on 4 November 1847 in Street, Lancashire, when Joseph Henry was 5 years old.

His half-sister Clara was born in 1848 in Manchester, Lancashire, when Joseph Henry was 7 years old.

His mother Ann passed away on 26 November 1857 in Manchester, Lancashire, at the age of 40.

His half-brother William Thomas was born on 17 June 1865 when Joseph Henry was 23 years old.

Joseph Henry Blackburne married Eleanor Driscoll on 10 December 1865 when he was 24 years old.

Joseph Henry Blackburne married Beatrice Lapham on 3 October 1876 when he was 34 years old.

His wife Beatrice passed away in January 1880 in St Olave Southwark, London, at the age of 26. They had been married 3 years.

Joseph Henry Blackburne married Mary Jane Fox in St Olave Southwark, London, on 16 December 1880 when he was 39 years old.

Joseph Henry Blackburne lived in Everton, Lancashire, in 1891.

According to Edward Winter in Chess Notes JHB lived at the following addresses :

- 16 Lucey Road, London SE, England (The Chess Amateur, October 1924, page 32 (address in 1879) and the 1881 British census (C.N. 4756)*).

- 116 Barkworth Road, Camberwell, London, England (1891 British census (C.N. 4756)*).

- 7 Whitbread Road, Lewisham, London, England (1901 British census (C.N. 4756)*).

- 45 Sandrock Road, Lewisham, London SE, England (Ranneforths Schach-Kalender, 1915, page 56, and Hastings Chess Club address list, 1922*).

According to chessgames.com :

“Joseph Henry Blackburne was born in Chorlton, Manchester. He came to be known as “The Black Death”. He enjoyed a great deal of success giving blindfold and simultaneous exhibitions. Tournament highlights include first place with Wilhelm Steinitz at Vienna 1873, first at London 1876, and first at Berlin 1881 ahead of Johannes Zukertort. In matchplay he lost twice to Steinitz and once to Emanuel Lasker. He fared a little better with Zukertort (Blackburne – Zukertort (1881)) and Isidor Gunsberg, by splitting a pair of matches, and defeating Francis Joseph Lee, ( Blackburne – Lee (1890) ). One of the last successes of his career was at the age of 72, when he tied for first place with Fred Dewhirst Yates at the 1914 British Championship.

In his later years, a subscription by British chess players provided an annuity of £100 (approximately £4,000 in 2015 value), and a gift of £250 on his 80th birthday.”

In 1923 he suffered a stroke, and the next year he died of a heart attack.”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess (OUP, 1984) by Hooper and Whyld :

“For more than 20 years one of the first six players in the world and for even longer the leading English born player. Draughts was the most popular indoor game in his home town, Manchester; he learned this game as a child and became expert in his youth.

He was about 18 when, inspired by Morphy’s exploits, he learned the moves of chess. In July 1861 he lost all live games of a match against the Manchester chess club champion Edward Pindar, but he improved so rapidly that he defeated Pindar three months later (-1-5=2—1), and in 1862 he became champion of the club ahead of Pindar and Horwitz.

Instructed by Horwitz, Blackburne became one of the leading endgame players of his time; and wishing to emulate the feats of L. Paulsen, who visited the club in November 1861, he developed exceptional skill at blindfold chess. He spent most of the 1860s developing his chess and toying with various occupations.

After winning the British championship, 1868-9, ahead of de vere, he became a full-time professional player.

Blackburne achieved excellent results in many tournaments: Baden-Baden 1870, third equal with Neumann after Anderssen and Steinitz; London 1872, second (+5-2) after Steinitz ahead of Zukertort; Vienna 1873, second to Steinitz after a play-off; Paris 1878, third after Winawer and Zukertort: Wiesbaden 1880, first equal with Englisch and Schwarz; Berlin 1881, first (+13=2 — 1), three points ahead of Zukertort, the second prize winner (Blackburne’s greatest achievement); London 1883, third after Zukertort and Steinitz; Hamburg 1885, second equal with Englisch, Mason, Tarrasch, and Weiss half a point after Gunsberg; Frankfurt 1887, second equal with Weiss after Mackenzie; Manchester 1890, second after Tarrasch; Belfast 1892, first equal with Mason; London 1892, second ( + 6-2) after Lasker; London 1893, first ( + 2=3).

He was in the British team in 11 of the Anglo-American cable matches, meeting Pillsbury on first board six times (+2-3 — 1), and he continued to play internationally until he was 72, long enough to meet the pioneer of the hypermodern movement Nimzowitsch, whom he defeated at St Petersburg 1914.

Blackburne had remarkable combinative powers and is remembered for his swingeing king’s side attacks, often well prepared but occasionally consisting of an ingenious swindle that would deceive even the greatest all his contemporaries. The tournament book of Vienna 1873 refers to him as ‘der schrwarze Tod [Black death] der Schachspieler’, a nickname that became popular.

His unflappable temperament also earned him the soubriquet “the man with the iron nerves’. Even so, neither his temperament nor his style was suited to set matches, in which he was rarely successful against world-class players. He had other chess talents: a problem composer, he was also a fast solver, allegedly capable of outpacing the great Sam Loyd. Blackburne earned his livelihood by means of simultaneous displays, for this purpose touring Britain twice-yearly, with a few breaks, for more than 50 years.

Before this time such displays were solemn affairs; Lowenthal, who would appear in formal dress and play for several hours in silence, was shocked when Blackburne turned up in ordinary clothes, chatting and making jokes as he played, and refreshing him self with whisky, (Blackburne confessed, however, that when fully absorbed in a game he never noticed whether he was drinking water instead,) Once, walking round the boards, he drained his opponent’s glass, saying when rebuked He left it en prise and I took it en passant‘

The illustrator Julius Hess depicted Blackburne in a New Yorker Staats Zeitung evening edition as sitting at a chesstable and beckoning: “Waitah! A whiskey and limejuice!”

He played his blindfold displays quickly, and with little sign of the stress that besets most blindfold players. Probably the leading blindfold expert of his time, he challenged Zukertort, a close rival in this field, to a match of ten games, played simultaneously, both players blindfold; but Zukertort declined. Many who knew and liked Blackburne subscribed to a fund which sustained him in his last years.

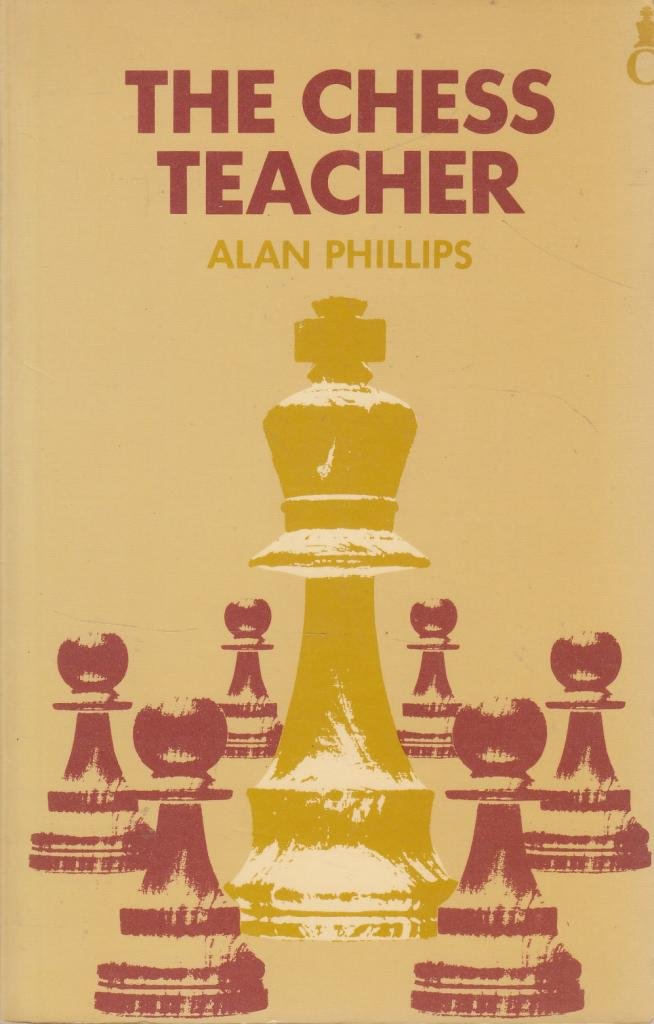

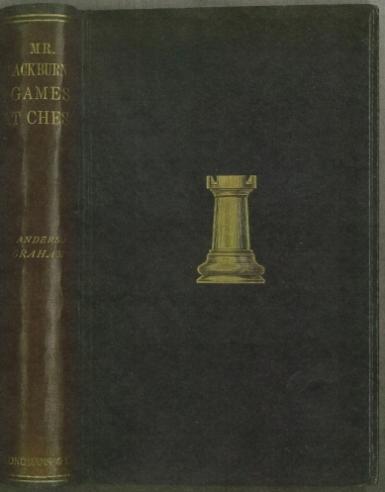

P. A. Graham, Mr Blackburne’s Games at Chess (1899) contains 407 games annotated by Blackburne and 28 three-movers composed by him.

A reprint, styled Blackburne*s Chess Games (1979), has a new introduction and two more games.

One of Blackburne’s contributions was the suggestion of using chess clocks rather than the archaic hourglasses.

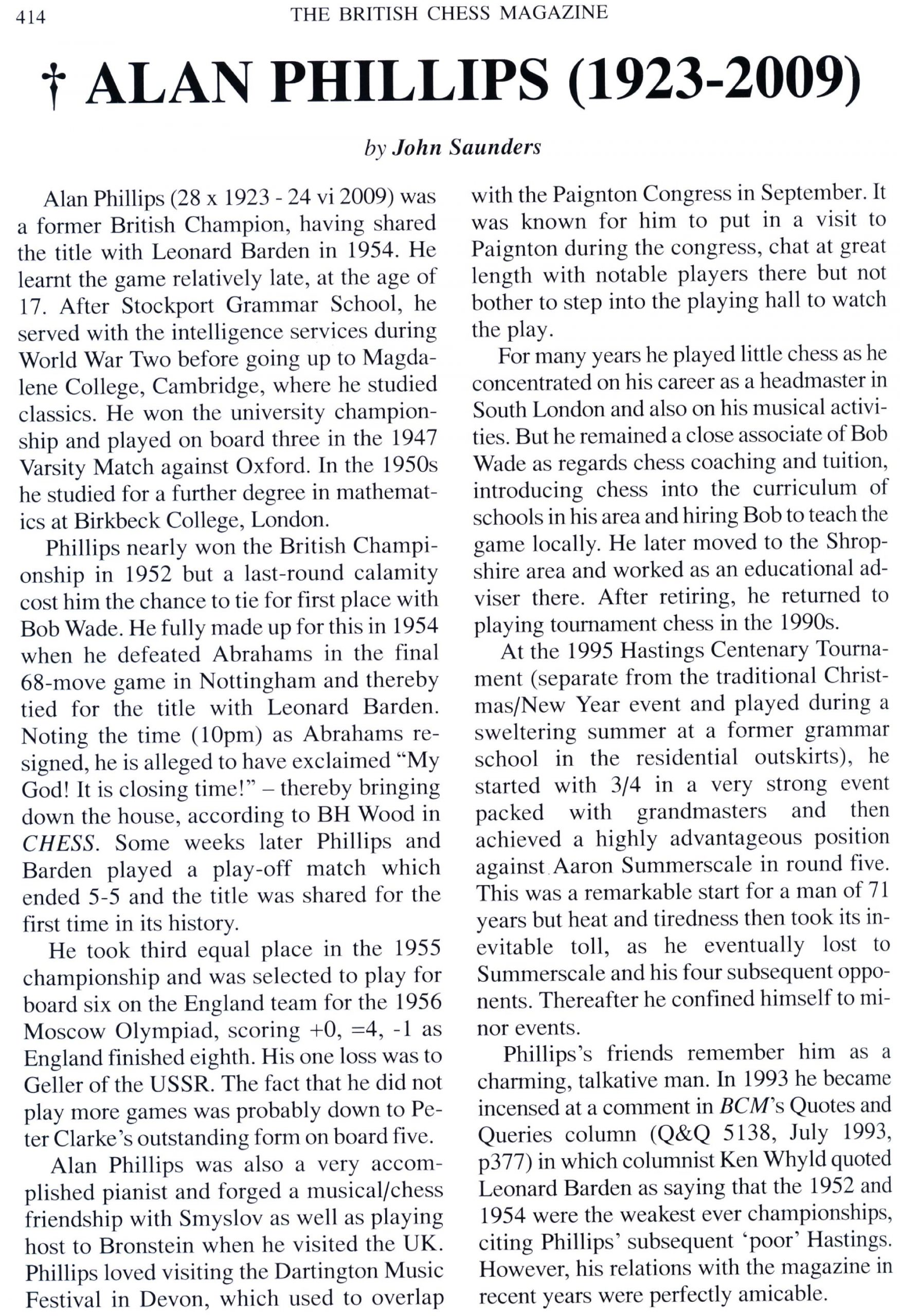

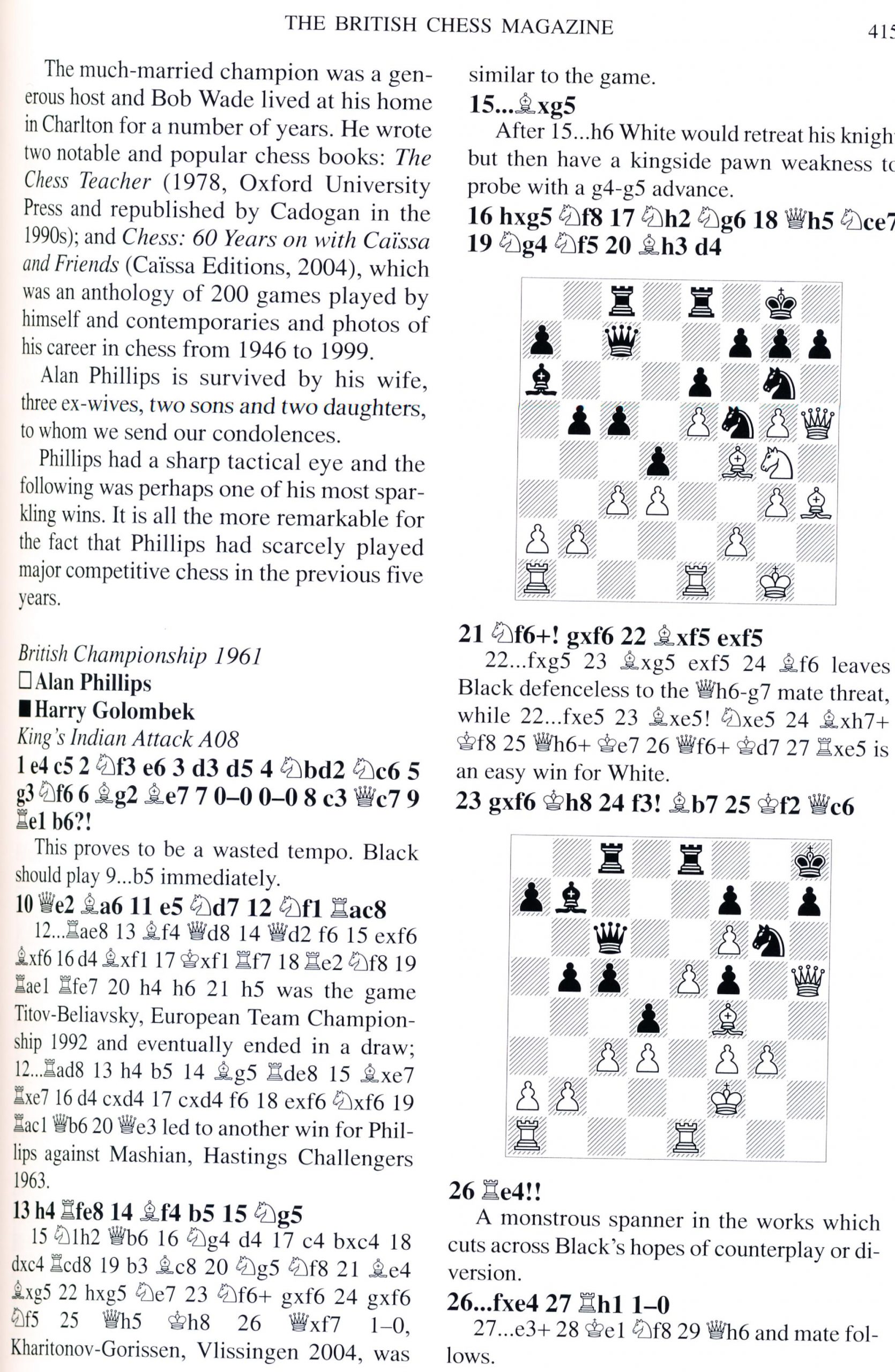

Here follows a reproduction of an article from British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXX1 (1961), Number 12 (December), page 340-342 written by RN Coles entitled “Early Days of a Great Master” :

“The only record of how J. H. Blackburne first, entered the chess world is the one provided by P. Anderson Graham in the introduction to his collection of Blackburne’s games. This has all the ingredients of a romanticized version of the truth-the first casual games in a temperance hotel, then entry to the important Manchester Club and a series of victories over ever stronger opponents until at last Pindar, Champion of the Provinces, comes along, plays the unknown youth and is defeated.

Reference to C. H. Stanley’s column in the Weekly Guardian and Express helps to supply a more accurate version. Young Blackburne’s earliest interest was in problems and he submitted one to the Guardian and Express which appeared in January, 1861, only to be found by several solvers to be cooked, Then silence till May 11th, when the column carries a note:

J. H. B. Problems received with much pleasure…Shall be glad to see you at the Club.”

Here are a couple of published problems. For a complete listing see below.

Manchester Express, 1861

#4. 6+4

The Field, 1893

#3, 7+6

Not yet a member, clearly. Nevertheless, he contrived somehow to meet Pindar outside the club and played some games-with him (two scores appear in the Guardian and Express, July 20th), and a set-match of five up was then arranged, still played in private (Guardian and Express, August 3lst), which “was terminated by Mr. Pindar winning a clear victory, the score being Pindar 5, Blackburne 0” (one game was quoted in the July “B.C.M.” and another score can be found in the Guardian and Express, July 27th.

“A second match was agreed upon, level games to entitle either player to the victor’s palm. The result … is calculated positively, to startle the chess world. The first game was scored by Mr. Pindar; of the next seven, Blackburne won five and the two remaining were drawn. ‘At this point Mr. Pindar resigned the match.” (Guardian and Express, September 7th, with the score of a Blackburne win from this match quoted February 1st, 1962.)

Only now does Blackburne appear to have joined the Manchester Club, meeting such players as Stanley himself for the first time (Guardian and Express gives the score of a casual game, November 9th), though Stanley later claimed personally to have discovered the young prodigy.

In November, 1861, Paulsen visited the club and the score survives of a casual game in which he beat Blackburne, who played a Winawer Variation of the French Defence long before Winawer ever came on the-scene (Guardian and Express, December,1861); Paulsen concluded his visit with one of his celebrated ten-board blindfold displays and not unnaturally the young Blackburne eagerly took a board; his defeat is No.25O in his games collection. This so stimulated him that he himself tried blindfold play and by January 20th, 1862, was able to give his first display against four boards, winning them all (Guardian and Express, January 25th, with one of the scores). This he followed with seven games on February 8th,

winning five and losing two. (Guardian and Express, February 8th) and finally ten games on February 8th, winning five, losing two, and drawing three (Guardian and Express,February 15th, which quotes the score of one game in addition to No. 254 in his games).

Inter-club matches were something of a rarity in those days and were regarded as of considerable importance when they occurred; one such was the annual Manchester-Liverpool match and in 1862 Blackburne took part for the first time, being matched against Wellington, another young player of promise who seems to have got no further; as many games were played between opponents as time allowed and these two young men played three, all won by Blackburne. (Guardian and Express, February 22nd, which quotes the score of one game in addition to No. 138 in the collection).

During this spring the rivalry with Pindar was renewed in a third match for the first five wins and after eleven games the score stood at 4 each, with three drawn (Guardian and Express, March 15th, quoting the score of the eleventh game), but I cannot find who won the last game. Since Blackburne was hailed as club champion this season, one must suppose he was the victor.

Such was his first club season. ln June, 1862, he played in the London lnternational Tournament and from then on his chess career was public property.

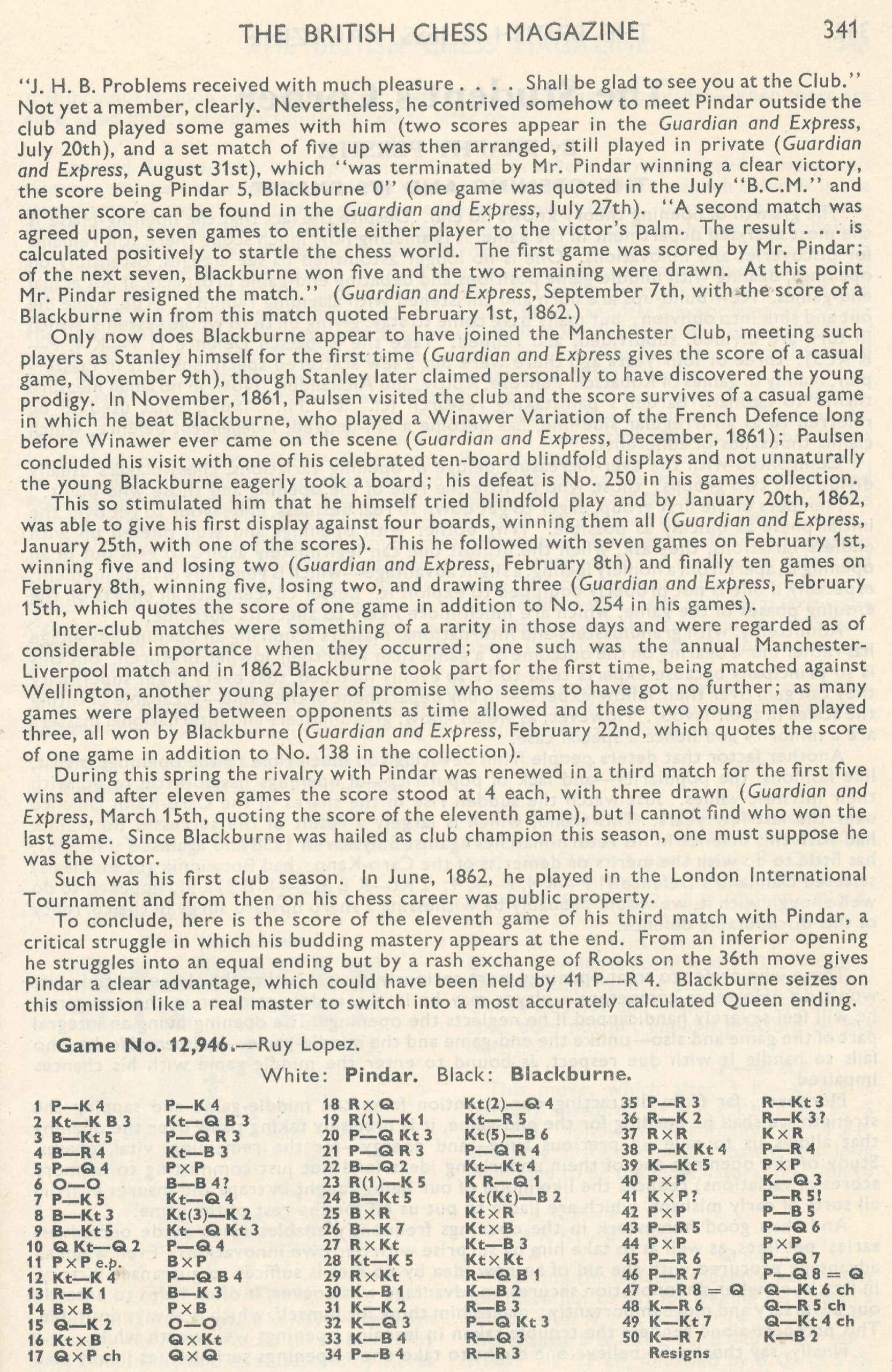

To conclude, here is the score of the eleventh game of his third match with Pindar, a critical struggle in which his budding mastery appears at the-end. From an inferior opening he struggles into an equal ending but by a rash exchange of Rooks on the 36th move gives Pindar a clear advantage, which could have been held by 41. P-R4. Blackburne seizes on this omission like a real master to switch into a most accurately calculated queen ending.

and here is the original article:

Many juniors and beginners will know the Blackburne Shilling Gambit (or Kostić Gambit) in some circles known (named by Julian Hodgson) as the ‘Oh My God’:

There are variations named after Blackburne as follows :

The Blackburne Attack in the Four Knights is

and the Blackburne Variation of the Dutch defence is

and a popular line in the Queen’s Gambit

are attributed to Blackburne in the literature.

According to The Encyclopedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977) by Harry Golombek :

“British grandmaster and highly successful tournament player who was one of the most prominent masters of the nineteenth century. He did not learn to play chess until the age of nineteen, but his natural gifts soon brought him into the front rank of British players, and in 1868 he abandoned his business interests and adopted chess as a profession.

Blackburne’s international tournament career spans an impressive fifty-two years from London 1862 to St. Petersburg 1914 – a total of 53 events in which he played 814 games, scoring over 62%. Although he rarely won international events, he generally finished in the top half of the table and his fierce competitive spirit coupled with his great combinative ability earned the pleasant nickname of ‘the Black Death’.

His most notable successes were =1st with Steinitz at Vienna 1873 (Blackburne lost the play-off match), 1st at Berlin 1881 ahead of Paulsen, Schallopp, Chigorin, Winawer and Zukertort, and 2nd to Tarrasch at Manchester 1890.

Blackburne won the BCA Championship in 1868 and for many years was ranked as Britain’s foremost player. In 1914 – at the age of 72 – he shared first place at the BCF congress in Chester.

In match play his success was mixed. He defeated Bird in 1888 (+4-1) and Gunsberg in 1881 (+7-4=3) but lost a second match to Gunsberg in 1886 (+2-5=6). He lost to Lasker (+0-6=4) in 1892 and was defeated heavily twice by Steinitz : in 1862/3 (+1-7=2) and in 1876 (+0-7=0), the latter of these matches being for the World Championship.

Blackburne excelled at blindfold play and in simultaneous exhibitions, which provided a major portion of his income. He died in Lewisham, a much respected veteran of eighty-three.”

Edward Winter discusses the Zukertort-Blackburne game of 1883.

Here is an article on chess.com by Bill Wall

Problems of the Black Death by Batgirl

Meson Database of JHBs problems

Here is his Wikipedia entry