Death Anniversary of Richard Griffith (22-vii-1872 11-xii-1955)

See Chess World, Volume 11, Number 6, June 1956, page 128.

Here is his Wikipedia entry.

Death Anniversary of Richard Griffith (22-vii-1872 11-xii-1955)

See Chess World, Volume 11, Number 6, June 1956, page 128.

Here is his Wikipedia entry.

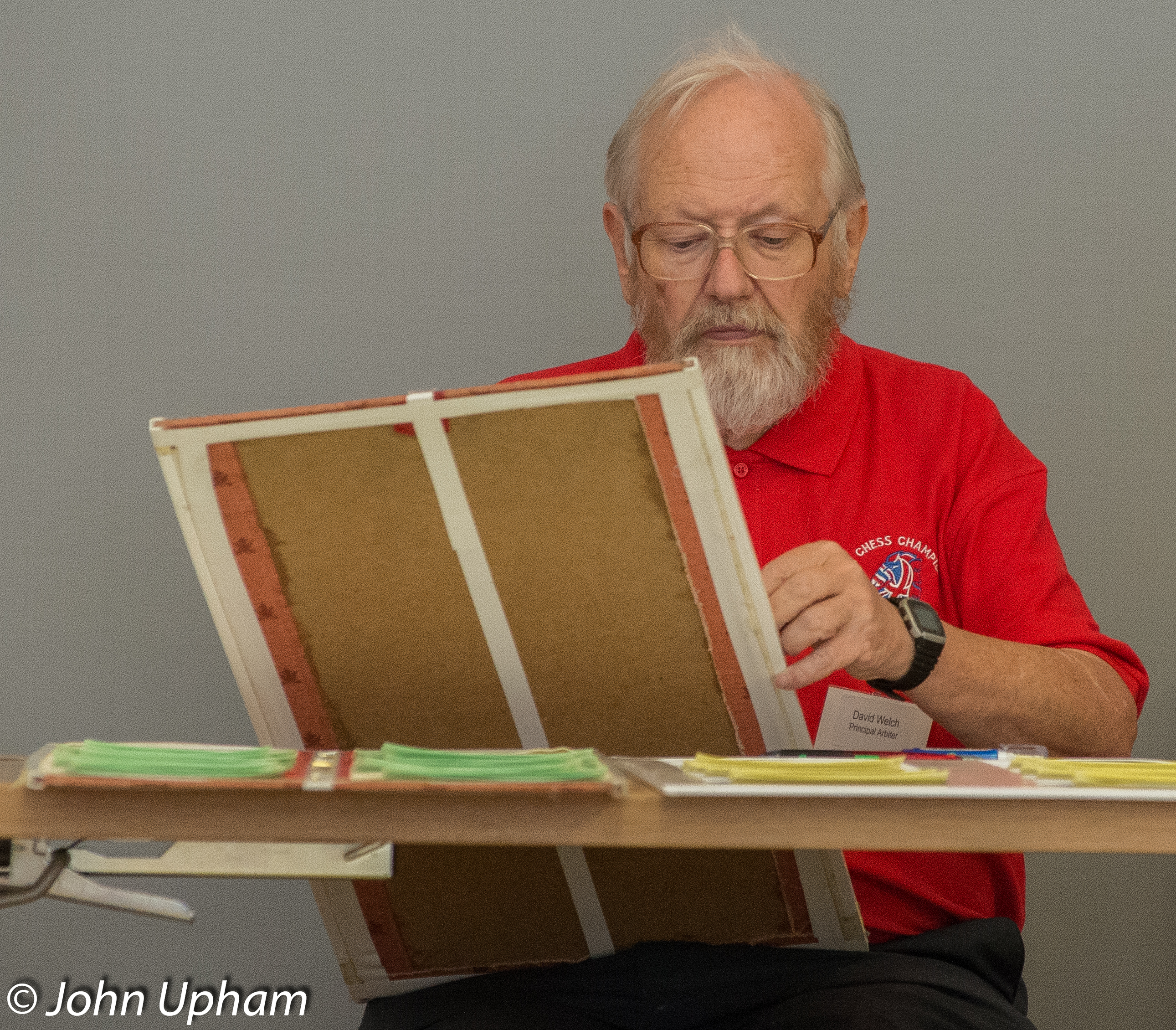

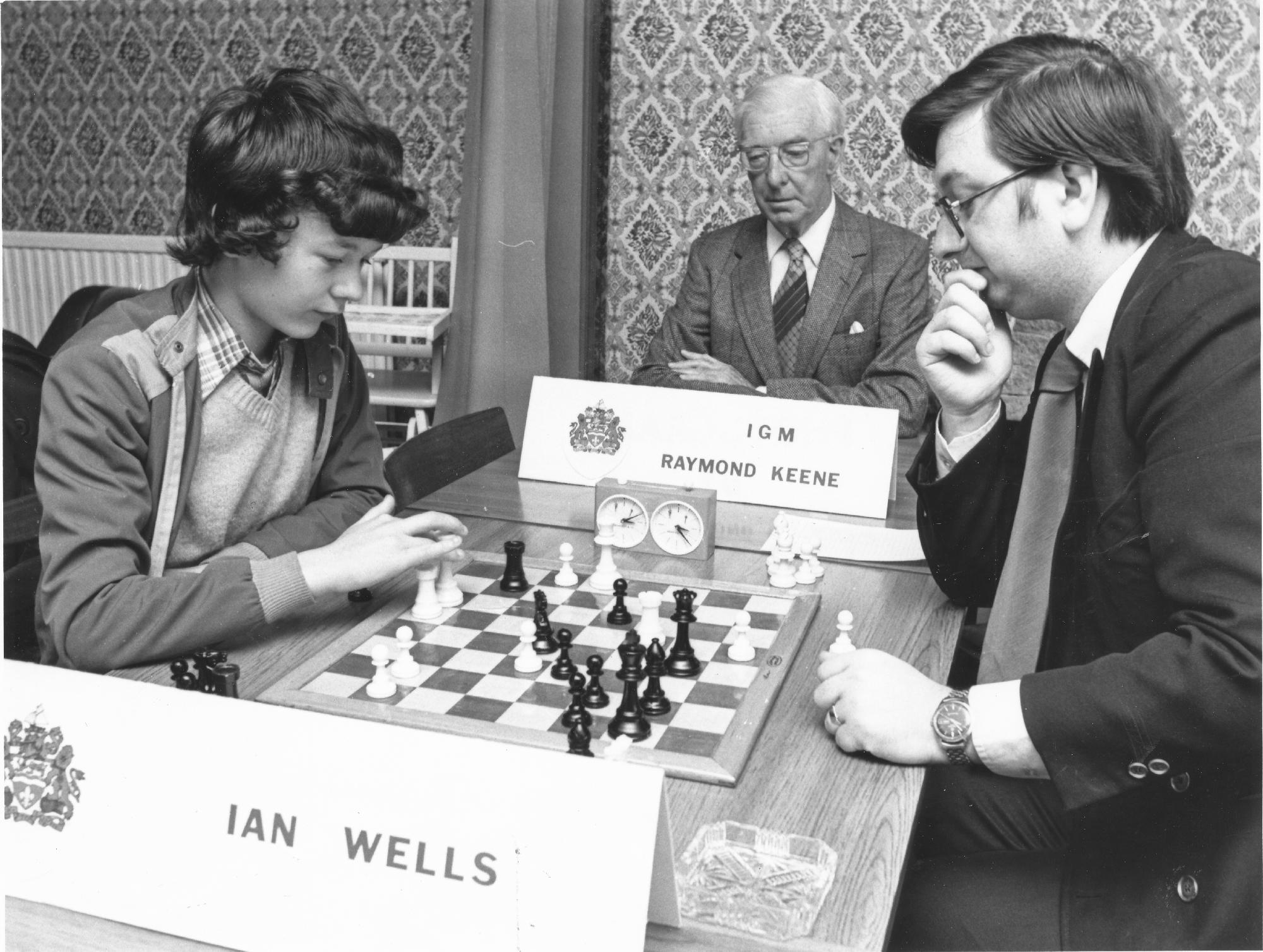

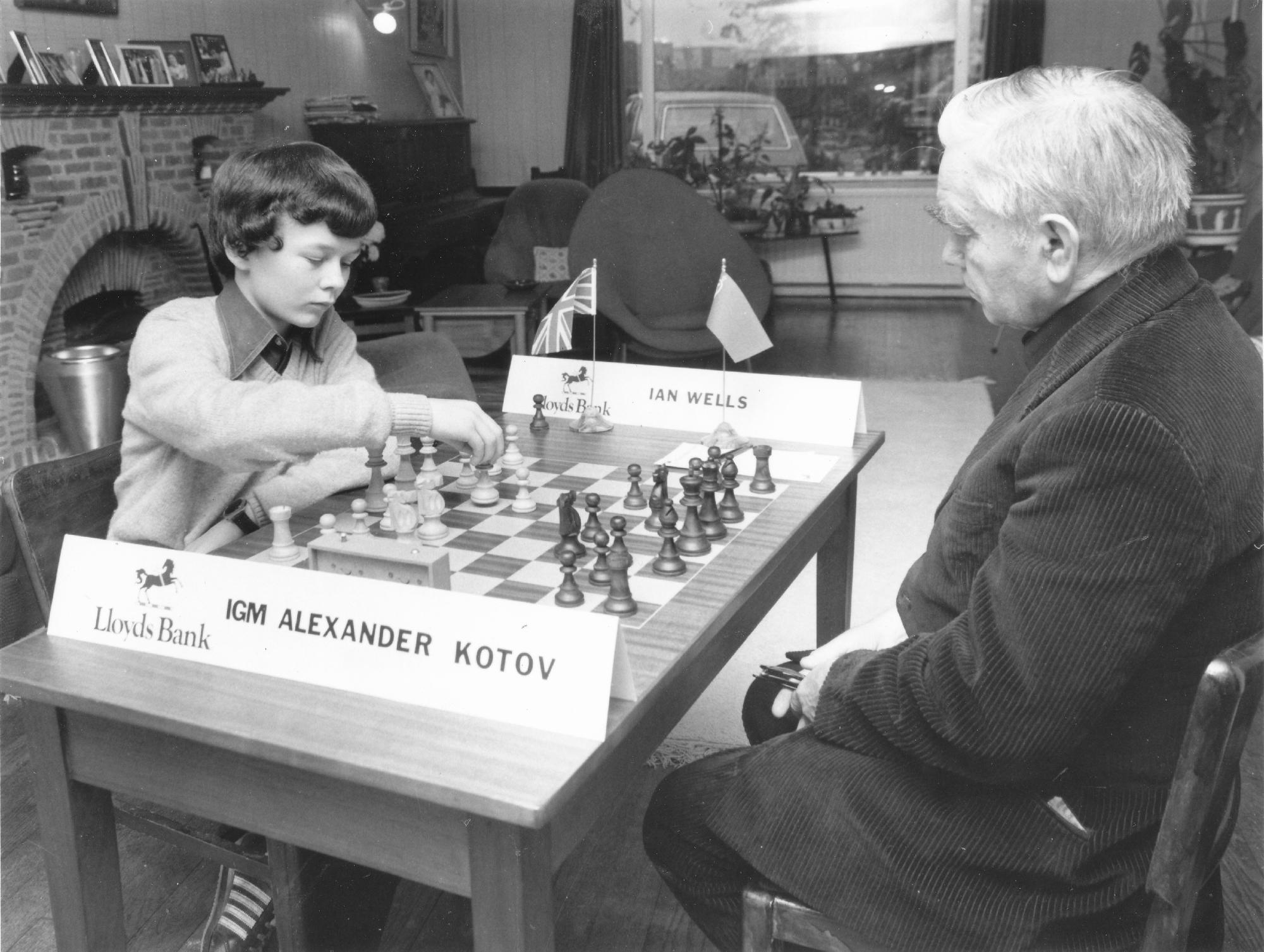

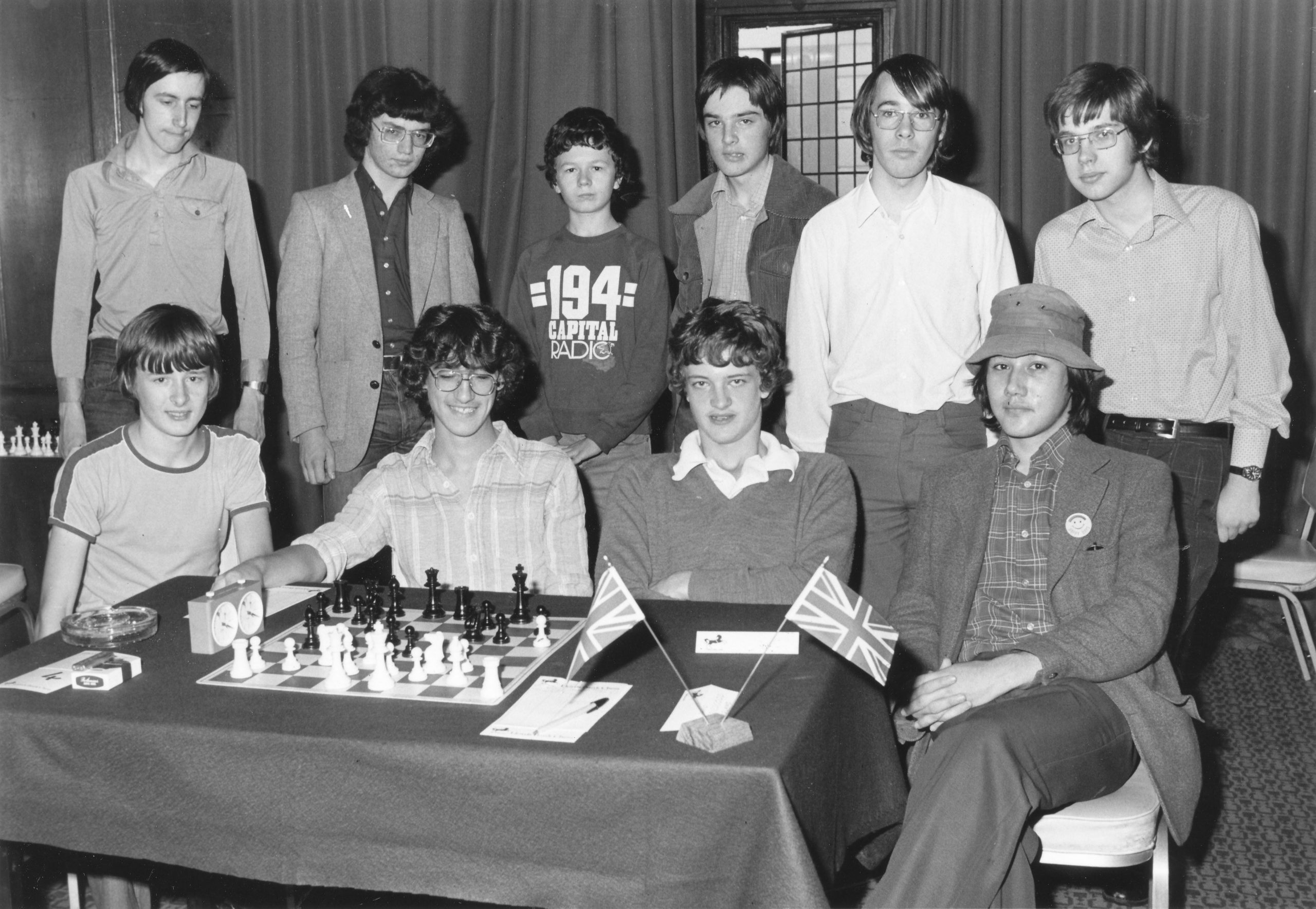

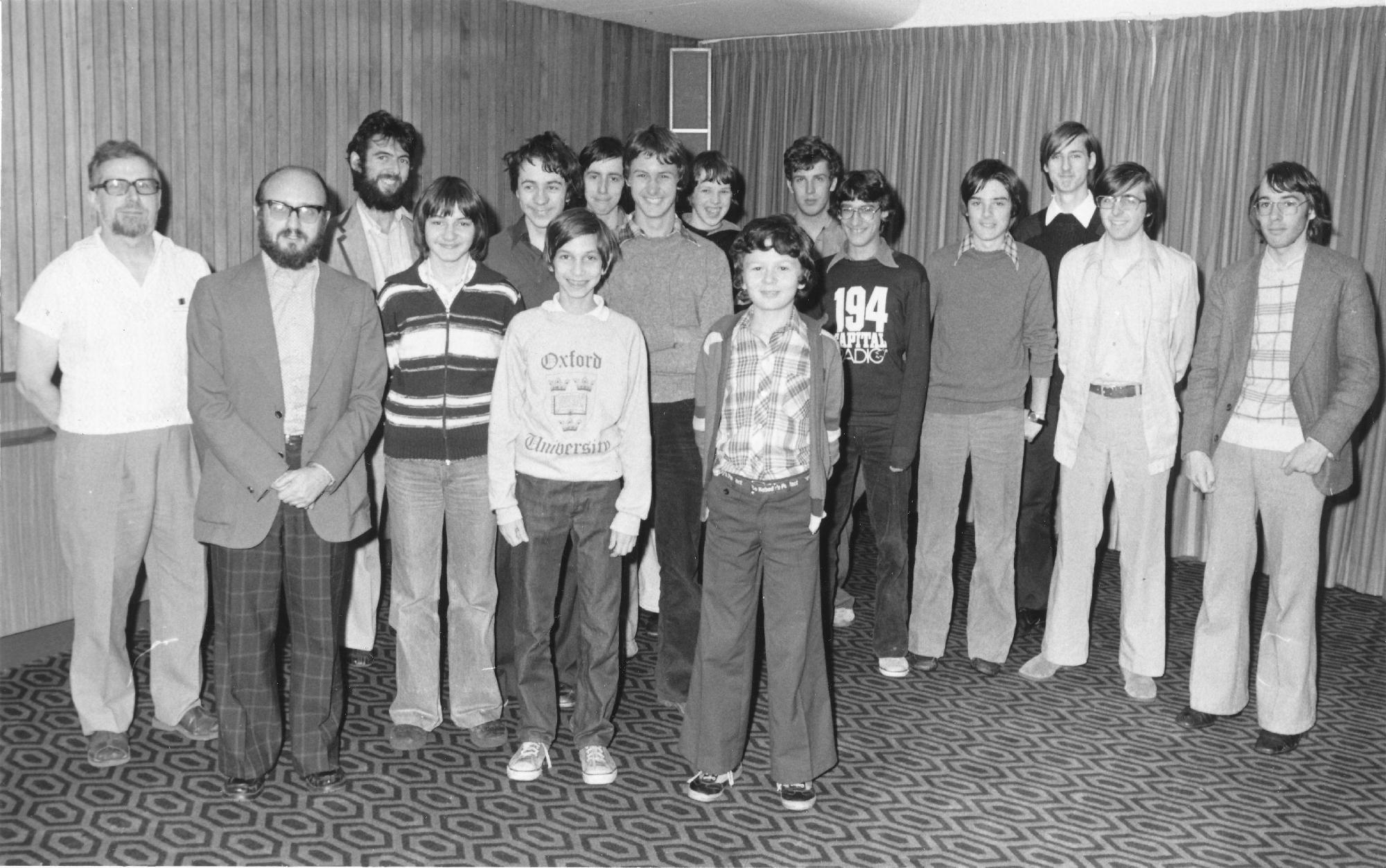

We remember Ian Duncan Wells who very sadly passed away on this day (January 25th) in 1982 aged seventeen years.

From Chessgames.com :

Ian Duncan Wells was born in Scarborough, England. He was awarded the FM title in 1982. At the Islington Open in December 1981 he finished 1st= with John Nunn and Tony Miles. Following a 5th= placing in the Golden Pawn of Brazil Junior tournament held in Rio de Janeiro he and other players went swimming outside their hotel. He got into difficulties and although he was brought ashore by lifesavers he died after six days in a coma.

Here is an excellent article from chess.com written by Neil Blackburn.

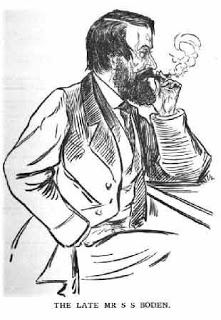

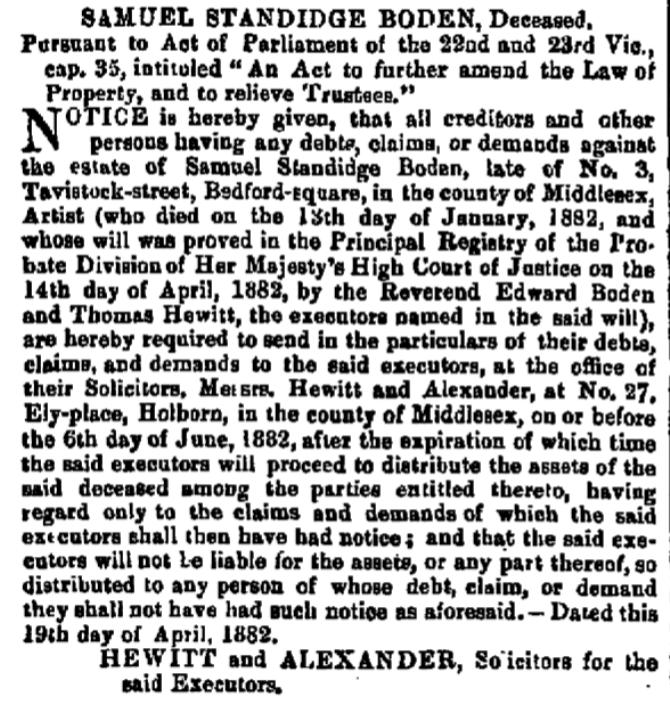

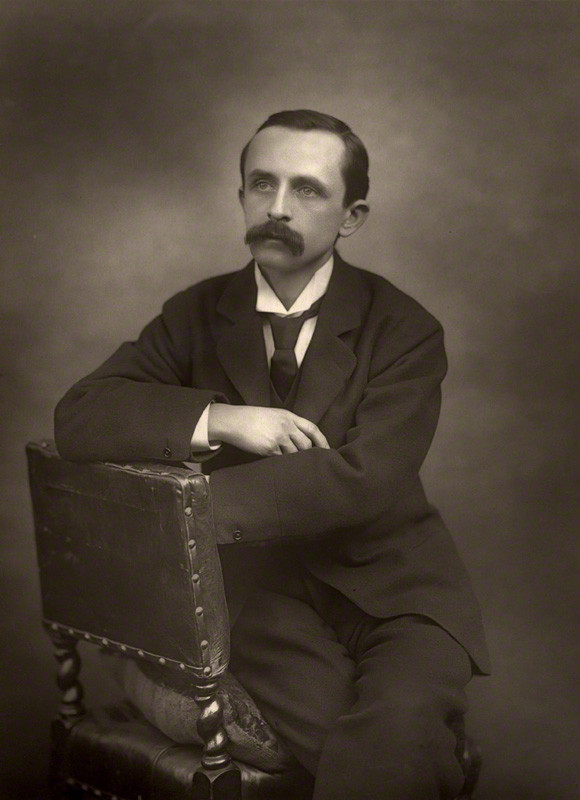

We remember Samuel Boden, who passed away on this day, Friday, January 13th in 1882 at 3 Tavistock Street, Bedford Square, Middlesex.

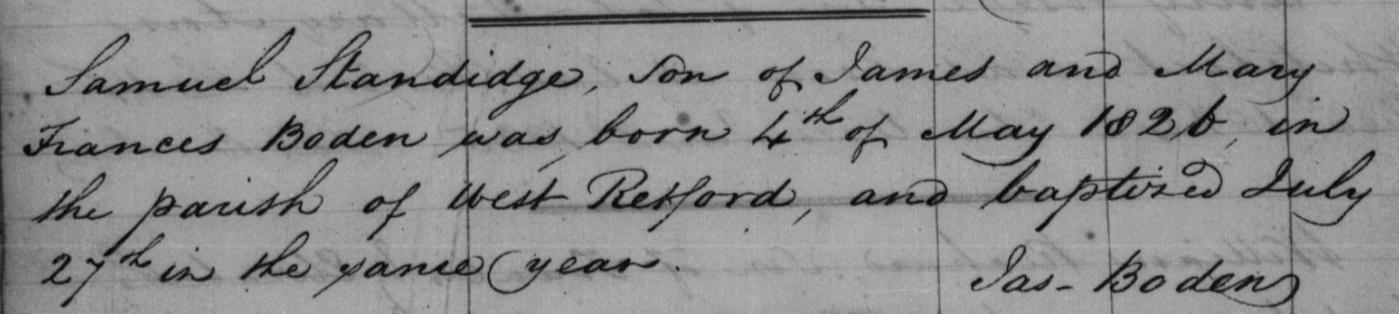

Samuel Standidge Boden was born on Thursday, May 4th, 1826 in East Retford, Nottinghamshire. His parents were James (b. 1795/96) and Mary Frances Boden (b. 1800/01).

(Several secondary and tertiary sources give the birth month as April. It would appear that a transcription error was responsible.)

James was an Independent Congregational Minister who worked in West Retford and was responsible for recording parish birth and baptismal (and probably marriage) records including those of his own children.

Samuel was baptised by his father (for the first time!) on July 27th at Chapel Gate (independent) Church.

Samuel had at least nine siblings and the details of these plus other family members (including multiple baptisms) may be found on Steve Mann’s Yorkshire Chess History.

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks :

“Boden was considered by Paul Morphy to be the strongest player in England in 1858. However, he is generally considered to have ranked below Staunton and to have been either the second of third strongest player, the other player being Buckle.

Born in Hull on 4th April 1826, Boden first came to the notice of British chess players when he won a provincial tournament in 1851. In 1858 he played two matches against John Owen , winning both, the first by +5 -3 =1 and the second by +5 -1. He played in very few major tournaments and his strength ws judged mainly from friendly games and small tournaments. He was the author of A Popular Introduction to Chess and conducted the chess column in The Field for 13 years.

He died of typhoid fever on 13th January 1882 and is buried in Woking, Surrey.”

According to Steve Mann :

“He was buried on 17/01/1882 at Brookwood Cemetery, Brookwood, Surrey. This cemetery was also known as the London Necropolis, having been specially instituted to take London’s dead at a time when space within London was becoming scarce. A transcription of the Surrey Burial Registers gave his name as “Samuel Standage Boden” and his age to be 55. The burial date, the deceased’s age, and the nature of the cemetery, together make it clear this was the chess-player, even though they misspelt his middle name.”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by David Hooper & Ken Whyld :

English player active in the 1850s. In 1851 he wrote A Popular Introduction to the Study and Practice of Chess, an excellent guide introducing the Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit which at once became popular. In the same year he won the ‘provincial tournament” run concurrently with the London international tournament. At Manchester 1857, a knock-out event, he came second to Lowenthal— he drew one game of the final match and then withdrew. In 1858 Boden defeated Owen in a match ( + 7=2-3) and he played many friendly games with Morphy, who declared him to be the strongest English player; since Staunton and Buckle had retired this judgement was probably right. Also in 1858 he restarted the chess column in The Field , handing over to de Vere in 1872. The column has continued uninterruptedly ever since. Besides chess and his work as a railway company employee Boden found time to become a competent amateur painter and an art critic.

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Harry Golombek OBE :

British master, considered by Morphy to have been the strongest opponent whom he played while in England (Boden’s record against Morphy in casual games was +1-6=4). Tournament results include 2nd Manchester 1857 and 2nd Bristol 1861. Chess editor of The Field 1858-1873. His name is linked with the Boden-Kieseritsky Gambit : 1.e4 e5 2.Bc4 Nf6 3.Nf3 Nxe4 4. Nc3 Nxc3 5.dxc3 f6 (article authored by Ray Keene).

Boden’s name is associated with a variation of the Philidor Defence:

and a line of the Ruy Lopez:

Most players will be familiar with this mating pattern that is Boden’s Mate using two bishops in a cross pattern.

Here is an example puzzle from 1001 Chess Exercises for Club Players that demonstrates the pattern :

White to play and checkmate.

Here is an in-depth article about Boden’s Mate from Edward Winter

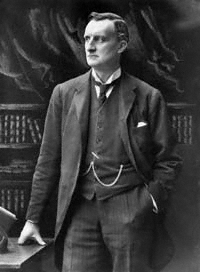

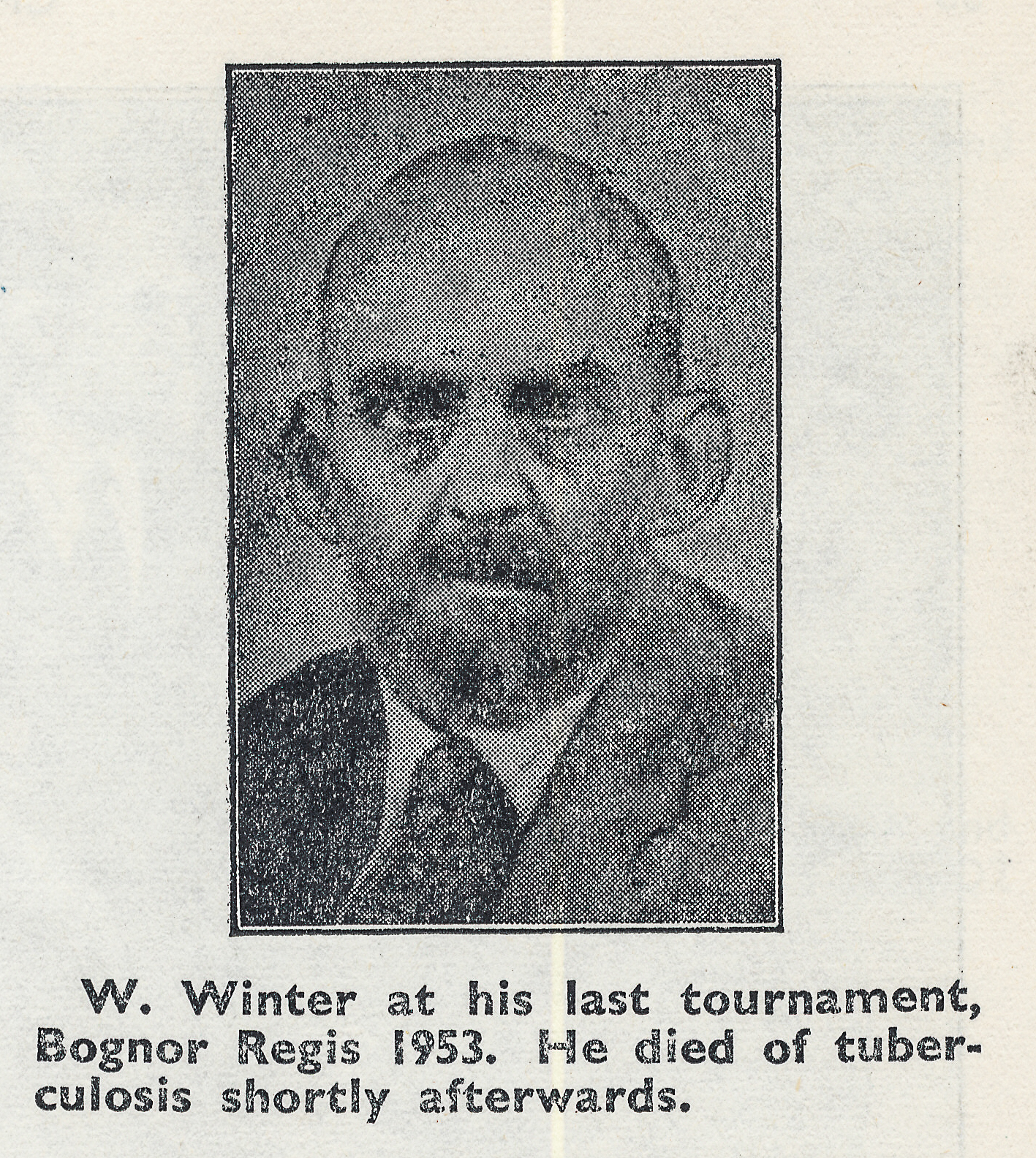

(For our biography of William Winter see here)

In the “Mid-October” issue of CHESS for 1962, (Volume 27, Number 418) we had the following announcement:

Edited by David Hooper, will be serialised in CHESS commencing with our next number. Nephew of Sir James Barrie, twice British Chess Champion, a lifelong Communist and freethinker, imprisoned for his political views, “Willie Winter”, with his Bohemian way of life, was undoubtedly the most colourful figure in British Chess for many decades irrespective of whether you agree with his views (most readers may not!), you will find him a delightful writer whose gifted pen draws you engrossed from page to page.

In the November issue of CHESS for 1962, (Volume 28, Number 419, pp.1-2) we had Part I:

Most people when I tell them that I am a professional chess player look on me as if I were some kind of fabulous monster. I don’t know why this should be so. Golf professionals, billiards professionals, and lawn tennis professionals are taken for granted, and surely chess players have far more need of professional assistance than the devotees of any of these pursuits. The work of the professional at every form of game or sport largely consists of teaching, and the complexities of chess are such that no player can hope to achieve even a modicum of success without the skilled guidance which only a. professional can give. I am glad to see that this is becoming widely recognised and far more aspirants are availing themselves of the services of the ‘pro’ than was the case when I first took on the job. There is of course much more to our work than teaching. I shall have plenty to say about the varied scope of our activities later on. Now I want to tell something about myself.

I was born at the back-end of last century at Medstead, a small village in the heart of Hampshire. Both my parents were Scots, my father being quite a distinguished scholar. Entering the University of St. Andrews at the early age of 16 he took honours in classics, and then finding himself rather at a loose end he took to the study of mathematics, won a scholarship to Clare College Cambridge and became a Wrangler. Probably he could have gained a Fellowship, but he had a passion for country life and took advantage of a small legacy to buy the house at Medstead and eke out his income by taking private pupils. I may say that he made a great success of this. He was a superb teacher, especially of rather backward boys, and was responsible for squeezing more moronic creatures past the entrance exams at both Oxford and Cambridge than one could have believed possible.

I must also mention that he was a very good amateur chess player. At one time he took lessons from the English professional master H. E. Bird, and possessed a number of his books. However, when he settled at Medstead lack of opponents compelled him to give up the practice of the game.

My mother also had claims to distinction, though perhaps rather vicariously. She was the youngest and the favourite sister of the great J. M. Barrie who seemed to tower over my boyhood like some colossal ogre. A benevolent ogre it is true, who produced handsome presents and provided the wherewithal for holidays which would otherwise have been quite beyond our reach, but I never felt quite sure when he might not start: “fee, fi, fo, fum!”

My mother’s desperate anxiety to please him in every thing was responsible for this attitude of mind: “What will Jamie think? What will Jamie say?” Actually he was quite harmless and, I imagine, did not think very much about us. We were far removed from the aristocratic circle which was already taking him to its bosom in Town.

My mother was by no means without talents of her own. ‘She was a pianist of considerable skill and had a singing voice of such quality that my uncle toyed with the idea of having her trained for the concert stage. Her poor health (she was always delicate) held up the idea and it was finally abandoned on her marriage and retirement into the country. She had her baby grand piano and practised Scottish folk songs in the drawing room, but Medstead was not I fear, capable of providing an appreciative audience. Unfortunately she was the complete opposite of my father in that she took not the slightest interest in the country avocations which were his joy.

Our fowls he regarded as nasty creatures who scratched up her flower beds, and an encounter with a gobbling turkeycock was sufficient to send her into hysterics. Looking back, I think she was happy enough when I was young and she could give her time to looking after me. When I became older and no longer had need of her care then she became unutterably bored and frustrated, and at odds with life in general. Unfortunately she took refuge in a sort of religious mysticism which undoubtedly affected her otherwise excellent brain.

There were four persons in her Trinity: God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Ghost, and God Sir James Barrie – who often became so inextricably mixed that it was difficult to know of which she was speaking. All this was of course a great grief to my father who was a Christian in the sense that it never occurred to him to be anything else but thought that religion was a thing to be trotted out only on Sundays.

He was however always kind, and it was only at the end of his life that he told me how much he had to put up with. A little I saw for myself, and at times it made me vaguely unhappy, but I soon forgot it in the abundant pleasures that were mine. “The Boynes,” as our house was called. was an ideal place in which to bring up a boy. It was a low white stone building standing in its own grounds and surrounded by a red brick wall.

The garden, apart from a drive to the front door and a croquet lawn had been allowed to run wild and it was ideal for such sports as Indians and Cowboys, Bushrangers or hide-and-seek. It possessed a marvellous collection of beeches, both the ordinary green and the cooper varieties, and in the spring and late autumn it was a sight to be hold. There was also a kitchen garden where we grew all our own vegetables but this was tucked discreetly away at the back of the house.

The house was all on the one floor, the only stairs being those leading to the cellar. It was built round a long passage lit in the day-time by a skylight, with three rooms opening off each side. This passage ran from the entrance hall to the door opening on the servants quarters, the aforesaid cellar, and some store rooms.

Around this rather curious architecture there hung a tale. The house was built in the Regency days by a gentleman by the name of Ivy, who after his evenings- potations was quite incapable of negotiating any stair. He lived alone apart from a man servant who, not unnaturally soon began to find existence somewhat wearisome.

Accordingly he developed the habit of slipping out to the village inn after he had ensconced his master with his nightly quota of bottles. Unfortunately one night Mr. Ivy felt more thirsty even than usual, and after finishing his last bottle rang for the servant to bring more. Receiving no reply to repeated jangling’s he decided to deal with the matter personally but he had overestimated his capacity, and when the butler returned he found his master dead with a broken neck at the foot of the cellar stairs. Filled with he hanged himself on a large hook in the back passage, and his ghost is still supposed to haunt the house.

The haunting takes the form of a butler carrying e tray, who at ten o’clock in the evening emerges from the service door, walks halfway down the main passage and then vanishes. I never saw this apparition myself, not to my knowledge did my parents, but the older. villagers always made an excuse to leave the house before the fateful hour of l0p.m, and one housemaid gave notice because. she said ‘Something frit her’. She could not, or would not, be more explicit.

In the December issue of CHESS for 1962, (Volume 28, Number 420-1, pp.28-33) we had Part II:

On the whole I had a very happy boyhood. Lessons I found fairly easy and I was able to pass such exams as were necessary without undue swotting. I did not share my father’s aptitude for mathematics and won little or no distinction in this field, but in my favourite subjects, history and classics, I was, I believe I can say without boasting, pretty good.

By the way it is a great mistake to assume that chess and mathematics have anything in common. Intuition and imagination are the qualities that mark the great chess player, and the fact that Capablanca and some other leading masters were also good mathematicians is purely coincidental. Alekhine was a complete dud at the science.

Like all small boys I think I was a bit of a horror, and I can remember being guilty of one or two unpleasant pranks. One of these, to my subsequent regret was played on my father. I have mentioned that he was a Sunday Christian and this was sufficient to give him the post of Vicar’s Warden, probably because he was the only man in the village capable of reading the lessons without mispronouncing the names of the Hebrew Kings and Prophets. After he had finished a lesson it was his custom to mark carefully the place in the big Bible at which to start on the following Sunday. Noticing this, I and another boy went into the church when all was quiet and altered the position of the marker, so that, instead of the description of the Mosaic law set for the day, my father found himself reading the sprightly adventures of Lot and his daughters. It was well for me that he never discovered the culprit.

Up to my introduction to chess my principal interest in life was cricket, my enthusiasm for which was fully shared by my father. He taught me the rudiments of batsmanship and bowled to me on the lawn, to the annoyance of my mother who objected to the green being cut up. Unfortunately I never made much of a show as a batsman, though later in life I developed quite a useful leg-break. Once or twice a year he took me to see the County team play at Portsmouth or Southampton. There were giants-in the Hampshire side in those days: C. B. Fry, Philip Mead the prettiest of all left-handed batsmen – but oh! so slow, those great-hearted bowlers Newman and Kennedy, and the gigantic Brown, the most versatile of all-rounders.

Occasionally too I was taken to London, either to Lords or the Oval, if there was a specially attractive match at either place. Those-were of course red letter days in my life, though two of them, I remember, ended disappointingly. An attempt to see M. A. Noble‘s all conquering Australian team play the M.C.C. failed because our arrival at Lords coincided with that of a thunderstorm, and the only sight we had of an Australian was Warwick Armstrong smoking his pipe on the visitor’s balcony.

This was my first visit to Lords, and I gazed with awe at the sacred turf, waterlogged though it was, of which I had read so much. On another occasion we went to the Oval to see the famous hitter G. L. Jessop, who was playing for Gloucestershire against Surrey. This time the weather was kindly but my hero was not, for he was caught at silly mid-on off the second ball he received. By way of consolation I remember we watched a century by Dipper, an admirable batsman, but, alas! no Jessop.

The love of cricket’ was shared by my famous uncle and indeed, in my adolescent days, it was the only subject on which I could talk to him. At one time he ran his own team, the ‘Allahakbarries‘, and wrote many amusing accounts of their performances, mostly, I fear, apocryphal. I once played for one of his teams and, though I failed with the bat, I redeemed my character by two tumbling catches at short leg, one of which sent back a Cambridge Blue.

Another cricket enthusiast whom I met when on a visit to my uncle was E. V. Lucas, for whose ethereal style of writing I had developed a boyhood passion. I was all agog to meet him, and great was my disappointment when, instead of the Shelley-like figure I had expected, there appeared a large fat man whose only subject of conversation appeared to be the dinners he had recently eaten. Then somebody mentioned cricket, and the whole atmosphere changed. Lucas became absolutely lyrical in his account of a Woolley innings he had just seen, and he and I were soon in deep discussion on the relative merits of the batsmen Jack Hobbs and Victor Trumper. and similar fascinating themes.

Besides cricket my principal hobby was exploring the countryside on foot or on my bicycle. Hampshire was a beautiful county in those days, quite unspoilt, and containing varied and attractive scenery. The trees of Selborne Hangar have to be seen to be believed and, in its own placid way the valley of the Itchen just outside Winchester is one of the loveliest things in England. There were few parts of the county within a radius of twenty miles or so that remained unexplored by me.

All these delights, however, had to take a back seat, after my first introduction to chess. This occurred when I was twelve years old, and its manner was curious. I have mentioned that my father was quite a considerable player in his younger days, but had to give up the game when he came to Medstead because of lack of opposition. It so happened that we acquired a new clergyman who challenged my father to a game of chess, and to his surprise and disgust beat him with, I remember, a variation of the Allgaier gambit.

This was just not good enough. My father had played at Simpson’s with some of the best in the land and considered himself in a far different class from any country parson! So out came the dusty board and men, down came the long disused books, and a turning point in my life had arrived. For about an hour I watched him, fascinated, then tentatively asked “What is that?” it’s chess” he replied. “Will you teach me?” At first he was reluctant as he thought I was too young, but I was so persistent that at last he agreed to show me the moves. The whole idea of the game fascinated me and from that moment I was determined that, whatever else I did, I would become a first class chess player.

My father at first restricted my lessons to an hour a day, after supper. But we had an intelligent housemaid whom I taught to play, and of course I browsed in his books when he was not using them. Most of them were the work of his old chess tutor H. E. Bird, whose influence, especially in the Sicilian Defence, can still be detected in my play.

When I was able to face my father over the board in an actual game he at first gave me the odds of the queen, but this badge of inferiority was soon reduced to rook, then to knight, until finally we played level. He disapproved of the odds of pawn and move, and pawn and two, on the grounds that they made regular openings impossible, an opinion which I heartily endorse. It was a great day for me when I first beat him on level terms, and a still greater when the parson, invited to ‘The Boynes’ for tea, not only succumbed to my father – that had now become quite a regular occurrence- but also fell an easy victim to my carefully prepared Sicilian Defence.

Once my father had come back to chess his enthusiasm never waned. He played until the day of his death, and the chessboard was on the table by his bedside when I saw him for the last time. As soon as he found he was really recovering his zest for the game he started to play by correspondence, and l, of course, helped him in his analysis. I could never quite understand my father’s attitude to these games. In my early days such assistance as I could give was of negligible value, but he continued to analyse with me when I was an acknowledged master, and on one occasion got Salo Flohr, accepted

challenger for the world championship, to work out a winning combination for him.

He had no hesitation in showing or even publishing games won with such assistance as his own. Yet in all other respects he was the most rigorously conscientious man I have met.

At fourteen I was taken several times to the Vienna Café in New Oxford Street, the most cosmopolitan chess resort I have ever seen. Representatives of every nation congregated there, and one could hear the word ‘check’ in a dozen different languages.

Germans and Austrians predominated as was only natural since, at the time of which I am speaking, these were the leading chess-playing countries of the world. Everyone was most kind to me, which may have been the reason why, later on, I was quite unable to accept the view that all the inhabitants of Germany and Austria ate babies for breakfast.

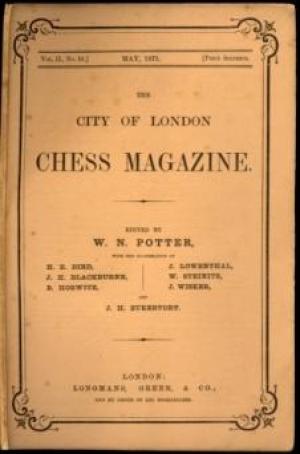

My real chess career began when I joined the City of London Chess Club at the age of fifteen. This was, and had been for many years, the leading club in the country, and everybody who had any kind of chess aspiration was a member. The club met in Grocers Hall Court, off Poultry, and was ruled with a rod of iron by its secretary J. Walter Russell. He was a real despot who would brook no kind of opposition, but there is no doubt that he did a tremendous amount of good work for the club. Later on his jingoistic attitude made him my bitter enemy, but in those early days he did everything to encourage me, and presented me with the bound volumes of the rare City of London Chess Magazine autographed by himself.

The players at the City were rigorously divided into five classes, each holding its own winter tournament. The winner of this, and the winner only, passed into the class above. After a test game against G. Wilkes, a strong class II player with whom I just managed to draw, I was placed in class III, Russell rightly thinking it would be discouraging for me to meet too strong opponents at my first attempt. I won every, game in this class in my first year, but failed in the second class or Mocatta Cup as it was called.

I enjoyed these trips to London. I stayed with my uncle but saw little of him as I was out in the morning before he was up and was usually in bed before he came in at night. He lived in Adelphi Terrace, in an enormous top floor flat supposed, and I believe rightly, to possess the best view in London. Certainly on a clear day it was possible to look right over the built-up area of South London to the Surrey Hills in the distance. I loved to sit, at my bedroom window and gaze out-over the Thames and the multitudinous lights beyond it, wondering what was to become my destiny when I too became a Londoner, as I had every intention of doing. One or two of my dreams, such as that I would become British Champion, materialised, but on the whole they bore little relation to the reality in store.

At the second attempt I won the Mocatta Cup quite easily, and became an acknowledged first class player, for the City of London set the standard for the rest of England. Then the war came, and with its advent I will close the last really happy chapter of this book.

To say that the war knocked the bottom of my life would of course be true, but that was an experience that I shared with the bulk of my fellow countrymen. I don’t suppose there was anyone in Great Britain whose life not changed by the war. In a few cases for the better – if one considers getting rich quick out of war profits a change for the better – but in the majority for the worse.

Where I differed from my associates was that I could not understand what was going on around me, Most of them took it in their stride, “It was a nuisance, but those damned Germans wanted taking down a peg or two, and it was up to us to do it. Anyway it wouldn’t last six months and then we would get back to normal. I just could not feel like that. It was not that I did not know what the war was about – on the contrary I felt that I knew it all too well’

I had studied history and elementary economic geography and knew that the mineral wealth of Alsace-Lorraine, filched from France in the Franco-Prussian war had made Germany the greatest industrial power in Europe. I also knew that the best markets were in the hands of others, principally of England and that German opportunities for capital expansion were thus circumscribed I knew that British industrialists were naturally anxious to keep these advantages in their own possession, and that their French colleagues were equally anxious to recover their lost provinces without which France was condemned to the status of a second-rate power. I knew, too, Russia’s craving for an outlet to the sea via the Dardanelles, now under the of Germany’s close friend Turkey. Here then was a situation in which big business in all the major European countries might hope to benefit from victory in a war but what possible concern could it be of ordinary folk like me and my father or those who worked in field, mine or factory?

I was soon to know. Foreign Minister Grey announced that England was entering the war to protect the neutrality of poor little Belgium, which the wicked Germans had violated.

This struck me as absolute poppycock, unworthy of credence by a child of ten, but England lapped it up with a fervour that nothing short of madness. Young men left their peaceful country avocations to rush into Khaki to have a go at these Germans before they caved in.

Even my kind gentle father, who could not bear to kill a mouse, suddenly became imbued with a lust for slaughter of people he had never seen, and who could not possibly have done him any harm. As for me I was prepared to think as badly as they liked of the German Kaiser and his entourage, but I could not regard our own hypocritical rulers in much better light. Still less could I be of England’s association with that barbarous tyrant, the Czar of all the Russias, whose brutalities had been the subject of much comment in the English press until he became our noble ally.

As for the Germans themselves, the ordinary people I mean, I could not think they differed in any marked degree from the French, the Russians, or ourselves. I completely discounted the tales of atrocities, with which my father used to regale us at breakfast, out of the columns of the Daily Mail.

As may be imagined my life at ‘The Boynes’ it that time was by no means a happy one. If I gave the slightest expression to my views everyone obviously thought that I was mad, and indeed there were times when I came to doubt my own sanity. I felt nothing but relief therefore when the time came for me to take up residence at Clare College, Cambridge, whence my father had graduated some twenty years before. Cambridge was a strange place in those war years.

The bulk of the undergraduates were already in the forces, but there was still a number in uniform training for commissions in the O.T.C. Pressure was put upon me to join these, but I firmly refused. For the most part they looked nasty pieces of work. There was of course the usual sprinkling of Indians and other Orientals, with some of whom I became very friendly. Today I can remember only two: an Egyptian named Talaat, an extreme nationalist who told me that I was the only Englishman in Cambridge whose throat he did not want to cut; and a charming Burmese, whose only fault was that his name was Moo Kow, which caused me some embarrassment when I had to introduce him in company.

Besides the budding officers and the Orientals there was another small group, serious-looking young men who included in their number most of the best scholars of the university. These were the anti-militarists, the ‘conchies’ waiting for the time when they would be dragged before a tribunal of local tradesmen who could grant them total exemption (very rare), offer them non-combatant service, or reject the appeal absolutely, which meant in effect, “Join the Army or go to gaol.”

Many who were given the choice of non-combatant service – preferred this last alternative. Towards -this group I naturally gravitated, and had the satisfaction of discovering that if I were mad, some very clever people including several Dons were mad also.

Another thing I found was that nearly all those anti-militarists were also Socialists, so I too became a Socialist. I am afraid that in those days I had a very hazy idea of what the term implied, but I knew that it stood for the workers and, surely, if anyone could stop this senseless slaughter it was the working classes. They, at any rate, had everything to lose and nothing to gain from continued bloodshed.

I knew that the International Conference of World Socialist Parties, meeting shortly before the outbreak of war had pledged themselves solemnly, that in the event of hostilities breaking out they would proclaim a general strike in all belligerent countries.

When the event actually happened, however, the party leaders, with a few exceptions, forgot all about the strike and scurried to join their national governments, where they denounced the enemy just as vociferously as their Conservative colleagues. In spite of this I still pinned my faith to the Socialist movement. Even in those days I realised that Socialism is greater than its leaders. Although on the whole I got on well with my new friends I soon found there was a number of differences between us. Most of them were absolute pacifists, that is to say they objected to violence or killing in any circumstance whatever, whereas my point of view was that I wanted to choose whom I would kill, and understand why I was to do it. Nor could I claim any religious objections to war.

Since August l9l4 my faith, such as it was, had been steadily declining, and Cambridge had finally destroyed it. We were compelled to go to chapel twice a week, as well as once on Sunday, and the continual prayers for victory for the British Army, which could only mean mass slaughter of Germans, struck me as disgusting hypocrisy in those who professed to follow the Prince of Peace, especially as their colleagues across the sea were imploring just the same thing – with colours reversed as it were. I had little use for a god who allowed himself to be harnessed like a mule to the national cannon.

I had a year of Cambridge before I became of military age, and during that time I had to face up to the first real dilemma of my life. Should I register myself as a conscientious objector on purely political grounds, or should I allow myself to be conscripted into the military machine as, of course, was the wish of my parents? At the time it was a terrible choice. All my own instincts were in favour of the first course, even though it might mean remaining in gaol as long as the war lasted. When I tentatively broached the subject to my mother it was received with a storm of emotion which quite broke my resolution. With tears streaming down her face she clasped my knees and- swore that she would rather see me dead than branded as a coward, and I really believed she would, too. I hastily told her that if she felt so strongly I would give in to her wishes, and all was peace again.

At the same time I made a private resolution that once I got into the Army I would apply every ounce-of ability I possessed, use every feint or subterfuge however unscrupulous, to avoid being put in a position where I had to kill or be killed. I had the strongest objection to taking the life of any potential Lasker or Tarrasch, and an equally strong one to their taking mine.

My friends at Cambridge for the most part considered my attitude to be a betrayal of principle, and so perhaps it was, but I had always dearly loved my parents, and I found the alternative course required more strength of character, or callousness, than I possessed. Once I had made up my mind things were not so bad. Cambridge, even in wartime, was a delightful place and I forgot most of my troubles in that best of anodynes, Chess.

The University club had naturally sunk to very small numbers, but those that-were left were very strong. We managed to organise a championship, which I won by half a point from Jonas Birnberg, a player who made quite a name for himself in London chess circles after the war. I also played in the championship of the town club, and defeated W. H. Gunston, a Don of St. John’s who was reckoned as one of the best players in England. He was much the strongest player I had yet met on even terms, and I was naturally very cock-a-hoop with myself, especially when I heard that he had not lost a game in the town championship for over twenty yeans. I could only tie for the title however, as I made draws with two of the lesser lights whilst Gunston won all his other games. Before the tie could be played off my time of liberty came to an end.

I am not going to say much about my army life. It was just plain Hell. My regiment was the Honourable Artillery Company, which I joined partly because its headquarters were in London and I hoped to be able to do at any rate some of my training there and partly because my people considered that my fellow soldiers would be of a rather superior type to those I was likely to meet in an ordinary infantry regiment’ I do not know whether this last supposition was true.

The only man whose name I can remember was subsequently tried for murder, but on the whole they were a decent enough lot of fellows. l cannot say the same of the officer and N.C.Os. Coarse and brutal, they seemed to take a sadistic delight in making my life as miserable as possible. I hated them with a hatred which I could not possibly feel for any German, and in all my experience with the H.A.C. I encountered only two men who not have been delighted to massacre. It is possible that the views that the view I held made me a difficult soldier, also that my sheltered life have rendered me unduly

sensitive to vulgar abuse, but looking back, and comparing these brutes with the very different types I served under in World War II, I cannot feel that my original judgment was far wrong. Enough of an unpleasant subject. Indeed I would leave the war years altogether if it were not that they played a certain part in my development as

a chess Player.

As I had hoped I did the first part of my servitude in London and, since I lived out of the Barracks at the Hampden Residential Club. I was able to get a good deal of chess in the evenings and on Saturday afternoons. I played chiefly at the Gambit Chess Rooms in Budge Row, kept by the Lady Champion, Miss E. Price.

Here I had a number of games on a professional basis with O.C. Muller, one of the last survivors of the Old Simpson Pro’s. Muller was a delightful chap with a a fund of anecdotes about chess players and others, which ought to have been true , even if they were not. He could keep an audience enthralled with these tales , which were absolutely without malice. In addition, he was a first rate chess teacher, and I earnt a great deal from him. He taught me how to build up a solid basis for the position, and the necessity for establishing such a basis before attempting any tactical adventures. Masterly restraint is another name of this, and it is the hall-mark of every first class player. It was Muller who gave me my first real insight into the complexities of the endgame.

I also had the opportunity of playing a number of semi-serious games with RHV Scott and D. Miller, two of the leading London amateurs. Scott was probably the most brilliant combinative played England has ever seen and had already won almost every honour except the British Championship, which fell to him in 1920.

Since those days I have played over hundreds of games, including the beautiful brilliancies of the modern Russian school, and Scott’s best combinations stand up quite well beside them. There were however weaknesses in his play which I shall discuss later. Miller was just the opposite type, a dour solid player exceptionally hard to beat. He is, I am glad to say, still with us, but Scott died a few years ago – he had been out of chess for a long time.

In these war days I did not go much to the City of London Club. Russell had already developed the jingoism which eventually drove him completely out of his mind, and I was soon at loggerheads with him. The first serious breach occurred on the question of the naturalised Germans. There was a number of these in the club. many of them British citizens since boyhood, and as loyal as Russell himself. Nevertheless to the latter everything German was tainted, and a special general meeting of the club was called to purge the club of the abomination. Together with Scott and most of the younger and stronger players I vigorously opposed the expulsion, but Russell had sent out a three-line whip to fellow dotards and, by a large majority , the naturalised Germans had to go. Among them was the club’s president, a man in his eighties. His expulsion broke his heart. He lived just long enough to alter his will in which he had left the club a large sum of money.

My first posting after London was Leeds, where at the Leeds club itself I found no strong players, but I was not long in discovering that in the neighbouring city of Bradford the British Champion F.D. Yates, and the Mexican master A.G. Conde, were in the habit of spending Saturday afternoons in a café known, in imitation of the London resort, as ‘The Gambit’. I was not long in making my way there, and found both masters helpful and encouraging. I played a number of games which each of them, and did not do at all badly. A comical feature of these exhibitions to Bradford was that some bright lad in the army had declared the city out-of-bounds to troops from Leeds, so that before I could leave at night Yates had to go out into the streets to watch for military policemen, surely the strangest job ever put on to a British chess champion.

There was another chess incident too, which was not without its comical side, although at the time it caused me a lot of annoyance. We had an old Sergeant-Major, a superior type to most of that kidney, who fancied himself as a player and insisted on having one evening each week with me. He was not a bad player, about knight class I should think, but of course he stood no chance with me level, and I simply dare not offer him odds. One week it happened that by an accidental blunder I lost a game, and to my surprise I was later asked If I would like a week-end pas, while on the other occasions when I won all the games I invariably found myself on the Sunday guard, or ‘stables’, a euphemistic term which meant sweeping up horse muck. I therefore set myself to try to lose one game at each session, and a hard job it was. If I had simply made blunders and allowed him to mate me, or win my queen, he would have smelt a rat, so I had to lay traps for myself hoping against hope that he would see this opportunity. I think some of losing games were among the cleverest things I have ever done on the chessboard, and I wish I had preserved them.

It was while I was at Leeds that a world-shaking event occurred. The Bolsheviks seized power in Russia. At the time I was aware that something had happened for far-reaching importance but, of course, I could only have the vaguest idea of its real significance. One thing I did know, the Bolsheviks led the Russian people out of the war and that alone was sufficient to make me inscribe the name of Lenin on my list of heroes. Why, of why, could somebody not do the same for us?

However, it was not to be so long. In 1917 it looked like another Thirty Year war. By November 1918 it was all over. At the time of the armistice I was at Catterick camp, a place which was surely one of the creator’s mistake, and I had been nearly driven to suicide by the persecutions of a lunatic Commanding Officer, who fortunately blew his brains out before I blew mine. As a student I had a right to priority discharge, and early in 1919 was back at ‘The Boynes’, a free man once more, full of hope for the future.

In the New Year issue of CHESS for 1963, (Volume 28, Number 422, pp.60-62) we had Part III:

I was back at Cambridge in a few weeks’ time, occupying the same rooms as my father which I had been unable to secure when I first went up. The University was a very different place from that which I had left two years earlier. It was now packed to capacity, and many would-be students were turned away from sheer lack of living accommodation. It was of course by no means the normal Cambridge. Most of those in residence had been through experiences of which the undergraduate of ordinary times would never have dreamt, and they were naturally a very different type from the lads fresh from school who make up the usual complement. These were hard-bitten callous men, for the most part without ideals or aspirations, only anxious to get their degrees and start on the serious business of money-making. In the boom period which followed the war everyone thought they were going to make their fortunes. By no means all, however, were like this and, although almost all my old friends had disappeared, I had no difficulty in finding new ones interested in one, at least, of my three activities, work, chess and politics.

These I kept as far as I could in watertight compartments, so as to avoid such social solecisms as inviting a Tory chess player to tea with a Socialist activist. Inevitably there was some overlapping, but I avoided any serious contretemps. I do not think I have mentioned before that I was reading Law, which, paradoxical as it may appear in a revolutionary like myself, I have always loved. I am of course speaking of Law, in the abstract, not of the laws-a very different proposition. I think the explanation lies in the fact that there is a great deal of similarity between the ploys and stratagems of legal practice, and manoeuvring on the chessboard. ln both the primary object is to outwit one’s opponent within certain carefully defined rules, and in both mental agility is the necessary ingredient of success. I believe too that Law, like a correctly developed game, is built on an inherently sound basis, the Common Law of England,

which, I think, will still provide the foundation for the vastly different legal system of the future world.

Naturally the masses of statutes and orders at present branching out from this Common Law are for the most part designed for the protection of private property and the smooth working of the complex capitalist system, but even these can sometimes be used by a smart left-wing lawyer for purposes very different from their drafters’ intentions.

This was what I hoped to do when I came to practise. Also there exists a mass of Trade Union laws, Factory Acts, Rights of Injured Workmen, &c., which is of direct interest to the working class, and provides the opportunity for a great deal of subtlety. Altogether there was plenty of scope for Socialist lawyers in the years immediately following the war.

As far as chess was concerned I found that the University club had completely fallen into stagnation, and I had to start to build it up I from scratch, with the assistance of that stalwart of Cambridge chess, B. Goulding-Brown of Trinity, and one or two other Dons. An advertisement in the Cambridge Magazine had an amazing response, and over sixty turned up at the ‘Blue Pig‘- otherwise the Blue Boar Hotel – where the clubroom was situated. I was elected president and, I fear, became dictator as well, but I think I made a pretty good job of it. I divided the members into three classes, arranging tournaments for each of them, and organized matches with both local and London clubs.

I also got up simultaneous exhibitions. Most of the matches were lost, as our players were totally without experience, but we did well enough to show that there was plenty of latent talent and, for the first time, I tried my hand at giving chess lessons.

One of the simultaneous exhibitions was by J. H. Blackburne, probably the last this grand player ever gave. I had heard that he was inclined to be slow and, knowing his tastes, arranged – for two bottles of whisky complete with glass, one at each end of the room. The device worked to perfection. He fairly galloped up and down, and finished the twenty boards in less than three hours without a single loss. He must then have been in his late seventies, a majestic figure, with his long white beard reminding one of some biblical prophet, except that his eyes beamed with benevolence instead of blazing in denunciation.

My next step was to revive the annual matches against Oxford which had been in abeyance since 1914. Usually these were played in London during the Easter Vacation, but as there was some difficulty this year about finding accommodation, our opponents offered us hospitality in Oxford. I was a one man selection committee and found it a difficult job. After the first three places the rest of the candidates were of very much the same strength or weakness – however one likes to put it. As finally constituted the team contained some names since well known in other walks of life. The third board was L. S. Penrose, now a professor at London University, and the fifth was occupied by Kingsley Martin now (l955) the editor of the New Statesman. Disappointed candidates for places suggested that his selection was due rather to his political opinions than his ability as a chess player, but he gave the best answer by winning brilliantly. In fact we all won, and the score of 7-0 stands a record for either side in these events.

On the first board my opponent was T. H. Tylor of Balliol with whom I have had many a stern struggle since. I was very proud of this game which was published in The Field with highly complimentary notes by the famous master Amos Burn. I spent the night in Balliol as Tylor’s guest, and made the acquaintance of the famous college port. I believe we played some friendly games afterwards but I have little recollection of them.

I left the Cambridge club with a membership of seventy-five and, though the numbers have dropped, I am glad to say it has flourished consistently ever since. I have taken every opportunity of visiting it as a member of the Hampstead touring side, and always enjoy reviving old memories. I think it is a pity, it now meets in a teashop instead of ‘The Blue Pig.’

The political side of my Cambridge activity consisted mainly of study. Naturally I read everything I could find about the Russian Revolution, and mastered the subject sufficiently to give a lecture to the University Socialist Society on the Soviet Constitution. It went down very well. I thought I was able to deal with a number of questions, and as I strolled home in the evening I was feeling distinctly pleased with myself when a dark figure suddenly loomed up in front of me and a raucous voice said,

“The proctor would like to speak to you, sir.”

I had inadvertently lit a cigarette while wearing cap and gown. It was a sad anti-climax.

The University Socialist Society, which ultimately achieved great importance, was in my day a very small affair. Its principal function was to engage a speaker to address public meetings in the town, a task of some difficulty as the speakers knew that they stood in grave risk of being mobbed by gangs of hooligans mainly drawn from the ex-officer undergraduates. These types mobbed the very mild Norman Angell and forced him to take refuge in the fire-station, but allowed a real revolutionary in Arthur MacManus to conduct his meeting in perfect peace and quietude – they had never heard his name. One of the speakers invited was G.B.S. who replied on a postcard that he thought it very cruel to invite him to Cambridge when he might be lecturing in some comparatively, peaceful centre such as Memel or Riga. These cities at that time were the scene of particularly savage fighting!

It was always a great grief to me that I never met Shaw in the flesh. At one time he lived opposite my uncle, and I have often seen him through the window moving about his flat. Although he did visit my uncle occasionally I never happened to be there at the right moment. I was once staying with Barrie when he went to lunch with Shaw, and he returned in a furious temper equally disgusted with the fare and the conversati6n. Both of them loved the theatre, that was the only point in common.

In addition to my Russian studies I began to acquire some knowledge of the philosophy of Marxism, which has been my support right through my life. In these studies I was very fortunate to have the guidance of Clemens Dutt, brother of the R. Palme Dutt who was at Oxford. Clemens had already graduated when I returned to Cambridge, so I was unable to give him a place in the University chess team in which he would have been a great asset, as he was a very fine player indeed, quite up to the best amateur standard:. I proposed him for membership of the City of London club, but he was turned down incontinently. I was told that Russell, who was by now completely ga-ga and must have mixed up Clemens with his brother, nearly had a stroke when he saw the name.

“If this man is elected,” he roared, “we’ll all be blown up as we sit at our boards.”

At Cambridge, Dutt and I used to spend every Sunday afternoon together discussing chess, and Marxism, as well as the immediate problems of the day.

Very happy hours they were, marred only by the Salvation Army who seemed to think a vacant piece opposite Dutt’s rooms the proper place for their most cacophonous efforts at soul-saving.

In order to gain some experience of the practical side of political work I joined the local branch of the Independent Labour Party and took part in two by-elections for the Local Council, both of which, if I remember rightly, were won by the Labour candidate. Even in the early-days after the war people were realising that things were not altogether for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

Not so pleasant a memory is waiting two hours in the pouring rain as part of a demonstration to welcome J. H. Thomas, who had just negotiated the settlement of a railway strike on terms more or less satisfactory to the workers. He was very popular then, but he did not make a good impression on me. His exaggerated illiteracy seemed to me highly bogus. I remained in the Cambridge I.L.P. until the majority of its members went over to the newly formed Communist Party.

Naturally, I went with them, and I have stood with the Communists ever since. It is now some time since my health compelled me to abandon active political work, and rumours have got about to the effect that I have changed or modified my opinions. I wish to take this opportunity of denying categorically any such reports.

I believed in 1920 that in Communism remained the only hope of civilization. I believe it with much more reason today when half the world is governed according to Marxist principles. I am not one of the so-called intellectuals who joined the Communist Party when it was ‘fun’, or a popular thing to do, and scuttled like rats when things became dangerous. Some of these are numbered with the Party’s most savage enemies, and I hold them in utter contempt. I am mentioning no names. Those whom the cap fits, let them wear it.

In the New Year issue of CHESS for 1963, (Volume 28, Number 423, pp.75-82) we had Part IV:

Great things were promised for the English chess world in 1919. A great tournament was being arranged at Hastings in which the unbeatable, the almost legendary, Capablanca had promised to take part.

To get into this was of course the height of my ambition, but how? It was clear that all I had yet done was to show myself a player of promise, and much more than that, was necessary to secure one of the coveted places in the Victory tournament. After much heartburning I decided my only chance lay in winning a match against one of the certain competitors, and therefore boldly challenged R. H. V. Scott. Scott, whose own place in the tournament was secure, was quite ready provided we could find someone

who would put up a stake and provide the necessary hospitality.

Here I had a stroke of luck. I found a patron. Mr. H. Rodney, a former president of the Metropolitan Club in London who then occupied a similar position at Hastings, had taken favourable notice of my play, and he agreed to pay all the expenses of the match as well as providing a prize of £20. “You won’t win” he told me, “but the practice will do you all the good in the world.” This was the general opinion of the chess cognoscenti. I was not so sure. As I have previously mentioned, I had played a great deal with Scott during the war and thought that, brilliant tactician though he was, there were certain weaknesses in his approach to the game of which I could take advantage. This kind of gamesmanship was an important weapon in the armoury of Dr. Lasker who, before any tournament, made a careful study of the weaknesses of each of his opponents, both as regards style of play and temperament.

It is entirely legitimate, and can prove very useful until one comes up against an opponent like Capablanca who had no weaknesses of any kind. ln Scott’s case, one of his foibles was an aversion to exchanging queens, and I took full advantage of this in the first two games of the match both of which I won with comparative ease; but Scott was not finished yet.’ In the third game he tied me up in a variation of the Sicilian which I had not previously seen, and in the fourth I made the fatal mistake in going for an early win of material and allowing him a king’s side attack. Things now looked bad for me. I had the black pieces in the fifth game and I dared not play my favourite Sicilian defence because I could not discover a satisfactory answer to his new line.

Fortunately I remembered that he had a predilection for a certain variation of the Ruy Lopez which I considered quite unsound and for the first, and nearly the last, time in my life, I met the open game face to face. The gamble worked. He played the dubious line, and I forced a win by a nice sacrificial attack.

This defeat completely demoralized him and he played the last game very badly, leaving me the victor by four games to two. Almost immediately after, I received an invitation to compete in the Master’s section of the Victory Congress, putting me of course in the seventh heaven of delight. I am eternally grateful to Rodney for what he did for me in those early days. He was the last survivor of that generation of British chess patrons who made possible the careers of Blackburne, Bird, and the other great professional masters. An aristocrat of the old school, and a true-blue conservative, he did not in the least mind my political opinions, and indeed told me that he preferred the Socialists to the ‘fat men who had done well out of the war’ now dominating his own party. Apart from chess he took quite a fancy to me and I was his guest on several occasions at his beautiful home on the East Cliff at Hastings, once the property of Henry James. He loved good food and drink, of which I was properly appreciative, though I could never accustom myself to his habit of drinking sherry for breakfast. I am very fond of sherry, but I do love my morning cup of tea.

The Competitors in the Master’s section of the Victory Congress were: J. R. Capablanca (Cuba), B. Kostich (Yugoslavia), M. Marchand (Holland), Dr. Olland (Holland) and A.G. Conde who, though resident in England, played as the representative of Mexico, together with F. D. Yates, Sir G. A. Thomas, R. P. Michell, V. L. Wahltuch, R. H. V. Scott, H. G. Cole, and myself from England. The tournament suffered from the fact that no players from the ex-enemy countries or from Russia were permitted to compete, but the presence of Capablanca was quite sufficient to make it a memorable event. I do not suppose any chess player, certainly none since Morphy, has ever caught the public fancy so much as ‘Capa’. Even non-players – people who did not know knight from a Pawn – knew his name or something like it, and I have been continually asked by people of this category, “Did you ever play with Capablanca” Possibly his appearance, which caused him to be much photographed, had something to do with it.

He was a trained diplomat. He was later known as Cuba’s Ambassador Extraordinary to the world at large, and certainly looked more like an Embassy attaché than a chess master. I am bound to say that my first impressions of him were not favourable. I have never been partial to glossy immaculate young men, and in common with other English players I resented his behaviour at the board. He never sat down, but when it was his turn to move’ strolled up to the table, surveyed the position for a few seconds, made his move, and walked away as if he were giving a simultaneous exhibition.

Probably he was justified in. holding the opposition in contempt, but he need not have shown it quite so blatantly. Later on he got rid of all his mannerisms and I came to appreciate his sterling character, particularly the way in which he upheld the dignity of the chess profession and the rights of his fellow practitioners. The chess world suffered a grievous loss when he died during the 1939 war, while still in his fifties. Whether at the period of which I am writing, and for a few years later, till 1925 to be exact, he was the strongest player that the world had yet seen, is a moot point. Certainly he was the hardest to beat.

From San Sebastian l911 to the match with Alekhine in 1927 his losses could be counted on the fingers, and this period included his world title match with Lasker. Certainly also no one has ever played chess so effortlessly. So perfect was his technique that he succeeded in making it appear an easy game – this proved his eventual undoing. He began to despise his his medium, publicly declared that chess was played out and would have to be made more difficult by the introduction of fresh pieces, and then proceeded to lose six games to Alekhine. Afterwards he revised his ideas. He ceased to rely on technique alone, and save his natural genius more play. He became more like the Capa of Pre-war years and his tournament successes thoroughly demonstrated his right to a return match for the world title. This is not the place to discuss the abortive negotiations between the two great masters on this subject, but all chess lovers must regret the consequences.

Not only was there no match, but relations between the two reached such a pitch that they would not speak to one another or even sit it the board together. It was all most unpleasant for those who, like myself, were on the best of terms with both of them. Great chess artists are a bit like children and need control, hence the necessity of F.I.D.E.

After Capablanca, the strongest player in the Victory tournament, was Boris Kostich, a colourful professional who did sufficiently well in American tournament’s during the war to secure backing for a match with Capablanca, in which he was well and truly crushed.

He was full of vitality and enthusiasm, a real go-getter who managed to arrange for himself a tour of the Native States of India from which he came back with sufficient money to buy himself a house in his native Serbia, and set up as a sort of country squire.

He also brought back a fund of stories about his adventures with elephants, tigers, harem beauties, and jealous murderous courtiers which I suspected to be more lurid than true. I got on very well with him and spent most of my spare time in his company. I have never put him in the very front rank of chess masters, but he had one extraordinary gift, a prodigious memory which enabled him to play over out of his head almost any game oi the present century and a good many of an earlier date. It was terribly hot at the time of the tournament, and almost impossible to sleep till the small hours of the morning, so Kostich and I used to sit on deck chairs al the edge of the sea while I would ask him for the score’ say, of Rubinstein v. Duras, Pistyan, 1912. A few moments concentration and out would come the moves accompanied by short expositions on the difficult points whilst I followed it on my pocket board. He was hardly ever at fault.

Naturally this colossal memory served him in good stead in his practice, but occasionally it proved a drawback, as when he spent, so long trying to recall what Blackburne played in a rook ending that he lost on the time limit. Not surprisingly he came second in the Victory tournament, followed by Yates and Thomas, the latter of whom played particularly well and would have won third prize outright but for resigning to Capablanca, through some hallucination, an ending in which he had at least a forced draw.

My own play was a great disappointment to me. Naturally I expected to lose to Capablanca, but I did not think it would happen in the childish way it did, and I collapsed almost as badly against Kostich. The one bright spot was a good victory over Yates, and I also beat Scott and Conde.

At the end of l9l9 I took my degree and left Cambridge. Although I never saw the University at its best I thoroughly enjoyed my sojourn there and always have an affection for the old place. No town that I have ever seen, with the solitary exception of Prague, has so thoroughly retained the atmosphere of the Middle Ages. It is always a pleasure to re-visit it. It was now necessary for me to make up my mind what I was going to do with my life. I had agreed with my parents that I should qualify as a solicitor but I managed to persuade them to allow me one year of chess before I settled down to the ‘serious business of life.’

At the back of my mind I had the sneaking hope that if I could gain some startling success in this year I might be able to make the game a profession.

Good old Mr. Rodney was nearly as disappointed over the result of the Victory tournament as I was myself. He knew and sympathised with my ambitions, and organised a match at Amsterdam between myself and Marchand, the champion of Holland.

The trip to Holland was a great thrill to me. I had never been abroad before except for one short holiday in France with my parents when I was quite a small boy, and everything was sheer delight. Amsterdam which later I came to know quite well, is of course a magnificent city in itself, and utterly and completely different from anything one sees in England. The canals with their streams of barges alongside the streets, the railway-train-like tramcars which are also pillar boxes, the cavalry charge of cyclists nine or ten abreast in what we term the rush hours, were a never failing source of pleasure, but I think that what impressed me more than anything was the sense of being in a neutral country, far removed from the hates engendered by the war.

Very typical was the sight which met my eyes when I went into a barber’s shop on the morning of my arrival. On one wall was a huge picture of Marshal Foch, and opposite to it another, equally large, of Marshal Hindenburg. I

detested these men and all that they stood for, but their pictures in the same shop really meant something.

As for the match itself, there is little to say. I played much better than in the Victory Congress, and put up a hard fight, but once again the strategical technique of the professional master proved too much for me and I had to admit defeat by two games to one with three draws. The match, played at the Amsterdam chess club, attracted a great deal of attention, and daily reports appeared in the Amsterdam Telegraph, each containing the game with excellent annotations. Among the spectators was a future world champion, Max Euwe, then still a student. Unlike most young players, who incline to arrogance – I was not deficient in this vice myself – Euwe was shy and diffident, and it was only when I got him to the board and he started to analyse that I realised that here was a great master of the future.

My opponent, Marchand, clearly saw the writing on the wall and was already preparing to abandon chess for a commercial career. “There is only room for one chess master in Holland” he said. I sympathised with him, for I also saw the writing on the wall and it said ‘SOLICITOR’S OFFICE’. My little pipe dream was over.

(Ed. The next few paragraphs detail WWs legal career and his politics. Readers of nervous disposition may wish to skip and resume discussions of chess further down.)

The first thing I had to do was to find a suitable firm to which to article myself. It was of course essential that the principals should be Socialists and the work should largely be concerned with the cause of the working class. Naturally I could not possibly take any interest in the work of a family solicitor or of any business looking after commercial companies. With the assistance of the Dutts I soon found what I was looking for. Scott Dickens and Thompson were a new partnership formed shortly after the conclusion of the war during which both principals had been in prison as conscientious objectors. Young though the firm was it had already handled the business of a number of Trade Unions; it also did a great deal of work on behalf of the tenants’ associations who had many rights under the Rent Restrictions Acts, if they would only find out what they were. Thompson, in particular, became a real expert on these complicated pieces of legal jargon, which drove even the judges quite frantic.

I started my new duties in January 1921, living at the Hampden Club, where I stayed at intervals during my military career. I think that I had better mention at this moment that I was quite without money of my own.

As an articled clerk I was not of course paid, and apart from occasional bits made out of chess and sundry writing, I was entirely dependent on a small allowance from my people. At first this was of no consequence as I was a creature of simple tastes, but later it was to have vital effects. For a time all went well, and it was an exciting world in which I found myself, in those early days of my life in London. The boom of the immediate victory had passed away, unemployment was developing on an unprecedented scale, and everywhere the workers were on the march to protect the improved conditions they had secured in the short-lived period of prosperity.

Nor were their activities solely concerned with working conditions and wages. By threats of direct action they had compelled the Government to abandon its war of intervention against the Soviet Union, and, under the leadership of a youthful communist named Harry Pollitt, had stopped the shipment of arms to Poland, in which country’ lay the last hopes of the interventionists led by Winston Churchill.

It was no wonder that I and many of my comrades thought that the revolution was just around the corner. Even chess had to take a back seat in my mind in those days. I concerned myself principally with the position of the unemployed. In 1921 there was no such thing as National Assistance, and when unemployment insurance became exhausted they were left to the tender mercies of the Guardians of the Poor.

These had an absolute discretion regarding what was necessary to keep an unemployed worker from starvation, and under Tory Boards, whose only concern was to keep down the rates, the plight of the unfortunate workless can be imagined.

Sporadic riots broke out all over the country and mass demonstrations were held, which at first took the form of collecting alms from shopkeepers and business men. This was quite the wrong tactic. It was the powers that be, the Government and the Local Authorities who had created the conditions which deprived these men of work, and it was their business to look after them.

The best elements of the unemployed soon realised this and formed the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement a contributory body, a sort of unemployed workers trade union in fact, with three main objectives: to compel the Boards of Guardians to pay adequate scales of relief, to force the State to take over responsibility for unemployed maintenance or work, and, as an ultimate objective, the overthrow of the capitalist system of which unemployment, poverty, and war, are the necessary concomitants. The leading figure in this movement was Walter Hannington, an engineer with whom I was to work in close contact for a considerable time.

I know, respect, and admire all the leading Communists in the country, but I will always have a specially warm spot in mv heart for Wally, because of his exuberant enthusiasm and good nature which neither frequent imprisonment nor privation could impair. He would make an ideal National Organiser for the Engineers, but, alas! his politics forbid.

Naturally all this working class agitation led to frequent clashes with the police, sometimes resulting in cases in which we were engaged professionally, and one of these led to a meeting that was to effect my whole life.

A certain Dennis Garrett, a leader of the Islington unemployed, had been convicted of causing breach of the peace and bound over to find two sureties of £25 each for his good behaviour. In default he was sentenced to three months imprisonment.

The police hated Garrett who was one of the most active and capable of the unemployed and did all they could to keep him inside, turning down surety after surety on frivolous or irrelevant grounds. At last the matter came into our hands, and we had no difficulty in securing a court order for the man’s release. I went to the gaol to

fetch him out, and was asked as a favour to break the news to his wife who lived in a back street off Essex Road, Islington. I climbed what seemed miles of dark ricketty staircase, knocked on a door, and saw Molly Garrett for the first time.

My readers may have noticed that I have had nothing to say about women. This is not due to reticence but simply to the fact that so far they had played no part in my life.

I am perfectly normal sexually, and as fond of women as most men, but the high incidence of venereal disease during the war, coupled with the nauseating talk on sex matters in the army, had disquieted me temporarily with the whole business.

I had a mild flirtation with one of the members of the Cambridge Socialist Society, and another, not quite so mild, with a red-head whom I met while exploring London’s Chinatown, but neither had any influence on my life. Somehow Molly was different. I am no hand at portraying sentimental emotions and do not intend to try here suffice it to say that after our first meeting we wanted to see one another again, and after several such we decided we wanted to be together always.

There was no objection on the part of Molly’s husband, who had a Kathleen of his own and seemed rather grateful to me for taking his wife off his hands, while the fact that we could not get married did not matter two hoots. In those days we considered marriage to be a bourgeois anachronism, and indeed have little use for it even now, except in so far as it provides a living for the Junior Bar – I shudder to think of the fate of freshly called barristers if the supply of undefended divorce cases dried up.

Ways and means for Molly and me presented a problem. The Hampden Club was for men only and I could not change my address without awkward questions from my people.

The difficulty was solved by retaining my membership of the club and and continuing to use it as an address, while we lived in a furnished room. For about two months everything went according to plan, but then came catastrophe. An unfortunate accident brought my father unexpectedly to London, he went to the Hampden club to find that I had not been living there for weeks, and the fat was in the fire.

This was the time when the fact that I was entirely dependent on my allowance assumed devastating proportions. My family issued an ultimatum, “Give up this woman or your allowance stops”. On my previous clash with my parents over the war I had given in to their wishes, but then I was alone. Now I had someone else on my side and I stood firm. So did they. My father told me privately that he himself would have turned a Nelsonian eye on the whole affair, and let things go on as before, but my mother and my uncle were adamant.

I always suspected that Barrie was the in the woodpile and my suspicions were confirmed when his solicitor, Sir George Lewis, sent for me to his office. Lewis apparently thought he could bully me into submission and only found out his mistake when I threatened to horsewhip him on his own doorstep unless he spoke of Molly with proper respect. I think he returned a very bad report of me. I hope he did. He was a thoroughly nasty little man.

However, all this did not alter my situation. The fiat went forth. My allowance was cut, and Molly and I found ourselves at the mercy of a world in the throes of a slump with unemployment increasing every day.

After a long council of war, we decided to stick it out. Naturally I had to give up my Articles, but we had certain assets. I had become a fairly competent public speaker, and had also established some literary associations, while Molly could often obtain casual work machining handbags, at which I believe, she was fairly efficient. Also we thought in our innocence it could not last for long. The miners were locked out, the engineers were threatened, and the unemployed agitation was increasing in intensity, every day.

Surely, we thought, with all this turbulence the hour of revolution cannot be far away. We decided to throw ourselves whole-heartedly into political activity and after much discussion settled on Bristol as the best place for our activities.

There were several reasons for this. For one thing my friend Clemens Dutt had taken a post at Bristol University – I am afraid that I was the cause of his losing it – and for another thing the unemployed committee whom I had met while on a visit to Dutt struck me as a fine body of men but without political or agitational experience. I felt sure we would be warmly welcomed and so it proved. A dwelling-place was found for us in a house in Philadelphia Street, a narrow alley in the centre of the town which has now, I believe, been pulled down. It was just what I wanted. It was cheap – 3/6d. a week was the figure we paid – and the street had the reputation of being so tough that the police were very chary of entering it, except in force. As I was pretty sure that my activities would sooner or later cause me to fall foul of the law, it was a great thing to feel that the natives, so to speak, were on my side.

The only drawback to our new home was that courting cats were able to gain access to the space beneath the floor boards, but one cannot have everything. The unemployed committee turned out to be, as I had thought, an excellent set of men, the most able being

Percy Glanville, a C.P. member who had gained some organizational experience in the A.E.U. and was also an excellent public speaker. He and I became great friends and on us devolved most of the propaganda work. The chairman was a man named Stewart, an anarchist of vast erudition who was quite a character in his way. He always wore a black skull cap which he would never take off under any circumstances. Once when he was ill I went to see him in bed and found him still wearing his old cap. I found out the reason when he was called to give evidence at the Police Court, and in spite of all protests denuded of his headgear. He was bald as an egg and the contrast between the vast shining ball that was the top of his head with his lined features and great hooked nose was extraordinarily comical. Poor Tommy Stewart, he developed tuberculosis and died soon after I left Bristol.

When I arrived I found the mass of the unemployed in bitter mood. Two days previously a demonstration to the Board of Guardians had been broken up by the police who had first driven a fire engine through the ranks of a perfectly peaceful procession and followed it up with a baton charge.

Bandages and sticking plaster were thus the order of the day, and several of the older men were still in hospital. British police are

usually spoken of with paeons of praise not only by visiting foreigners but by writers like Ted (Blue Lamp) Willis who really ought to know better. I am quite prepared to admit that they compare favourably with their opposite numbers in other countries. They are less corruptible than the American, and less brutal to the ordinary criminal suspect than their French counterparts but, when it is a question of a working class and particularly an unemployed demonstration they show themselves in their true light as the- strong-arm men of the propertied classes.

I am speaking of what l know, I have taken part in-at least six perfectly peaceful demonstrations where these thugs have gone into action, lips drawn back in a snarl, striking out indiscriminately at young and old, men and women. The mounted men, Ally Sloper‘s cavalry we called them, are even worse than the others. It is their mission to break up an orderly march by making their horses trample on the demonstrators toes and this creates a mob which falls an easy prey to the men on foot. It may be objected that the real blame for all this lies with the men at the top who give the orders, and no doubt they must bear the chief responsibility, but the rank and file cannot be exonerated. Every recruit to the Police Force knows what he may be called upon to do, and it is no life for a decent

young working man.