Death Anniversary of Brian Harley (27-10-1883 18-v-1955)

From chesscomposers.com :

“Brian Harley composed mostly two- or threemovers and wrote many books to make chess problems more popular: for instance his “Mate in Two Moves” inspired Geoff Foster’s first steps into problem dom.

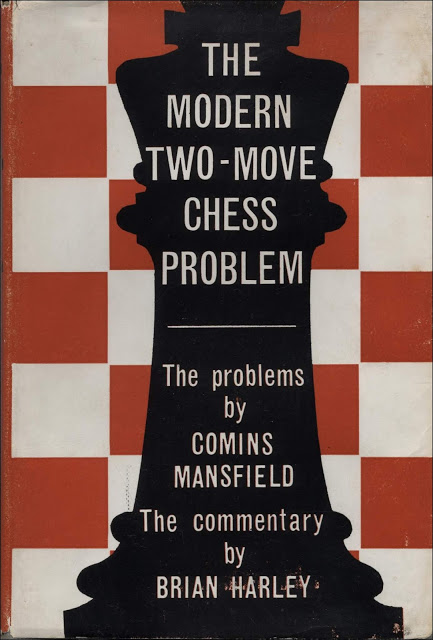

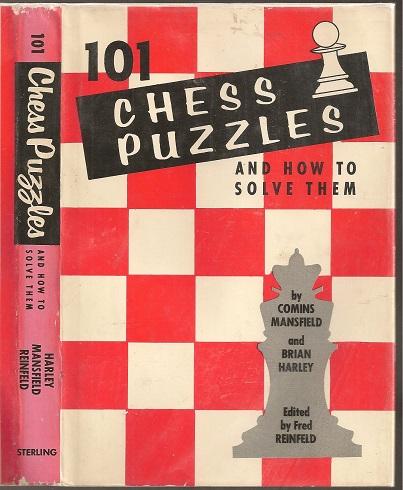

Harley’s “The Modern Two-move Chess Problem” written in collaboration with Comins Mansfield is probably the best known of his efforts.

Brian Harley was the inventor of the term “mutate” for the block problems with changed mates. He was the president of the British Chess Problem Society from 1947 until 1949. In his honour, each year the British magazine “The Problemist” awards the best twomover problem with the “Brian Harley” award.”

and Edward Winter writes about Brian Harley (scroll down a little).

Here is BHs obituary from British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXV, Number 9, pages 284 – 287 written by S. Sedgwick :

“With the death of Brian Harley on May 18th,1955, the chess problem is the poorer by an authoritative exponent, and a writer of unusual clarity and popular appeal. His sudden passing at his home at Bognor Regis will be mourned. by a very wide circle of friends; to his wife and son, with whom he enjoyed an enduring happiness, we extend our deep-felt sympathy.

Born at Saffron-Walden, Essex, on October 27th,1883, Harley was educated at Wellingborough and Haileybury. Qualifying as an actuary he entered the National Provident Institution, in whose employment, apart from War Service, he passed his professional life, until his retirement in 1947.

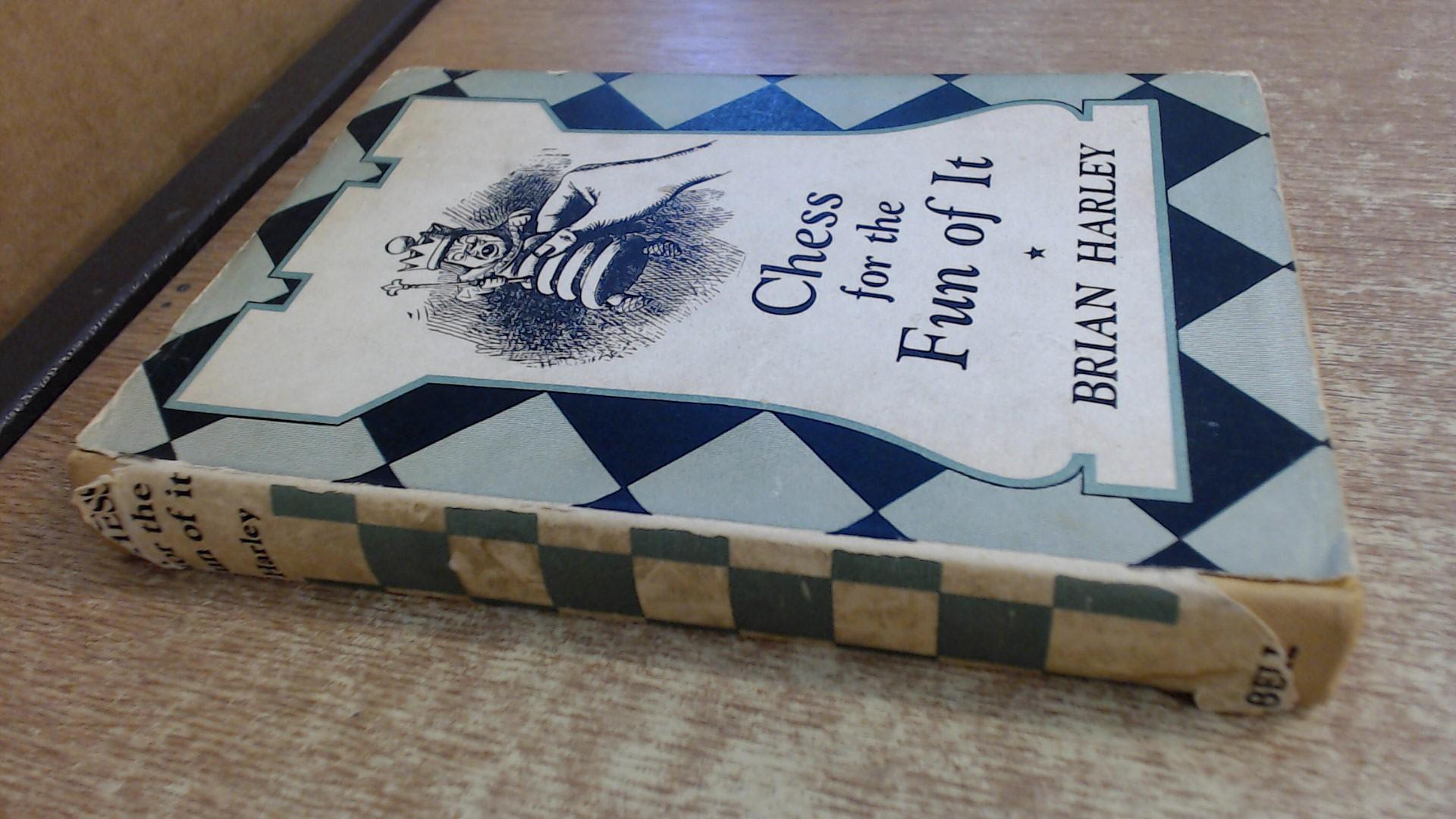

As a player he had initially a considerable reputation, above that enjoyed as a problemist. Two books, Chess and its Stars and Chess for the Fun of it, reflect this aspect of his chess work. When playing was eventually renounced for problems he still retained his love of annotation, bringing to this a wide knowledge, larded by the apt witticism and an approach that was neither superficial yet avoided the pitfalls of pedantry.

His first problem appeared at the age of fifteen, in 1898. Whilst Harley’s early period has some noteworthy items, it lacks the verve and distinction of his later output, following his awakening of interest in the mutate in 1916_and the fertile years following his appointment as Chess Editor of The Observer, London, in 1919. In England under the lead o[ Phillip Williams in the Chess Amateur, the mutate had sprung into popularity during and after the Great War, with Harley among its ardent exponents. He continued the cult in his Observer column, where he did much to popularize it. It is possibly symbolic that when Williams died in 1922 his travelling board and men should pass to Harley; it would be difficult to find a comparable instrument that has witnessed the genesis of so much concentrated chess devilry, implicit in all mutates, as this board used first by Williams and then by Harley.

In July, 1919, Harley published his system in the Good Companion folder. This paper, the outcome of much thought, attempted to evaluate the constituent parts of a chess problem on a semi-mathematical basis. Point values were set down for the elements in White keys, Black defences thereto, and the resultant White mates, the summation giving values for comparison with other works similarly treated. In an accompanying paper on the block-change it was here that Harley introduced the term “mutate,” the word passing, without cavil, into the current idiom. Under the evocative power of Harley’s work and pen his Observer feature from 1919 onwards has come to rank with the great columns of the past. No composer of substance was absent from its pages and the result is a collection of works and descriptive criticism that has enriched the chess literature of the world. Early on, Harley came to know the late Godfrey Heathcote, and the welcome presence of the great composers name in the column gave it a sublimity possessed by no other comparable English journal. Harley’s comments on his contributors work was one of the many attractive features of his column. He kept the popular approach very much in mind without unduly over-weighting it; this, blended with a brand of humour all his own (often literary in character), and a grasp of essentials drove home the salient points of a problem to the uninitiated solver with a peculiar vividness. He could ‘be incisive when wanted, technical when he pleased, his gentle rebuke for the inferior production or undetected flaw could not be other than well taken, authoritative without ostentation, his succinct criticisms are now legendary to be treasured and repeated when the occasion demands. An incorrigible faddist in his regard for the short threat in the three-mover, Harley seldom admitted this type to his pages, pleading aversion by solvers. He conducted over one hundred solving contests during his column’s life; these weekly battles of wits affording enormous pleasure to all concerned.

To his column came the established composer and the hesitant, possibly young, beginner. To this last group Harley gave every encouragement and unreservedly of his advice and help. There must be few British composers who have not felt his benefit directly, through the medium of his wonderful letters, lit all the way through by the warm glow of an endearing personality.

Harley’s constructive powers brought him to the front rank of the world’s composers. His output of 450 includes long range work in four and five moves and in later years, sui-mates. In the chess-men he found a pliable medium for the realization of an unusual vision and creative gift. In the two-mover he gave to the mutate much substantial and classic work. He appears to have given to this type more specialized attention than any other in the two-move field. Elsewhere in this length his work covers a wide variety of themes with a strong liking for task renderings. A composer with few serious constructive foibles, his mode of expression, in consequence suffered little. His was not the temperament to linger with one theme and squeeze it dry. One or two renderings of the theme on hand and he would pass to the next. Hence the diversity of his work which imbues it with especial charm. To underline this point one could indicate, almost at random, Harley’s entries in the multimate tourney of the Cleveland Chess Bulletin. Certainty the theme had few attractions for him but his entries showed how superbly such problem ideas could be clothed.

In the three-mover Harley has graced both sides of the aesthetic fence, and that with distinction, giving equally to the strategic and model-mate genre. His friendship with Heathcote however influenced him considerably here and one is inclined to the view, that in this length, Harley held firmly to the eternal values in chess art. In both types Harley attained especially in task renderings, rare heights of complexity and construction. His lighter mood showed to the full-to the incipient solver much of the low cunning of which the three-mover is capable.

He came to the sui in the late forties. When Heathcote was convalescing in London, following an operation, Harley took some specimens with him when he visited his friend The ensuing discussion stimulated Harley to further experiments and the authentic touch of the great master of technique is evident in his work here also. Harley gave many of his works to his own “Observer” column but did not neglect the other sources of publication. To quote his own words his ideal problem was “a mixture of art, science, humour, and puzzlement.” His best work shows brilliantly his love for the integration of the beautiful and the true inner essence and spirit of chess.

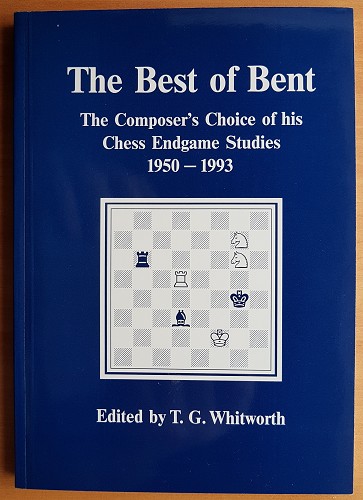

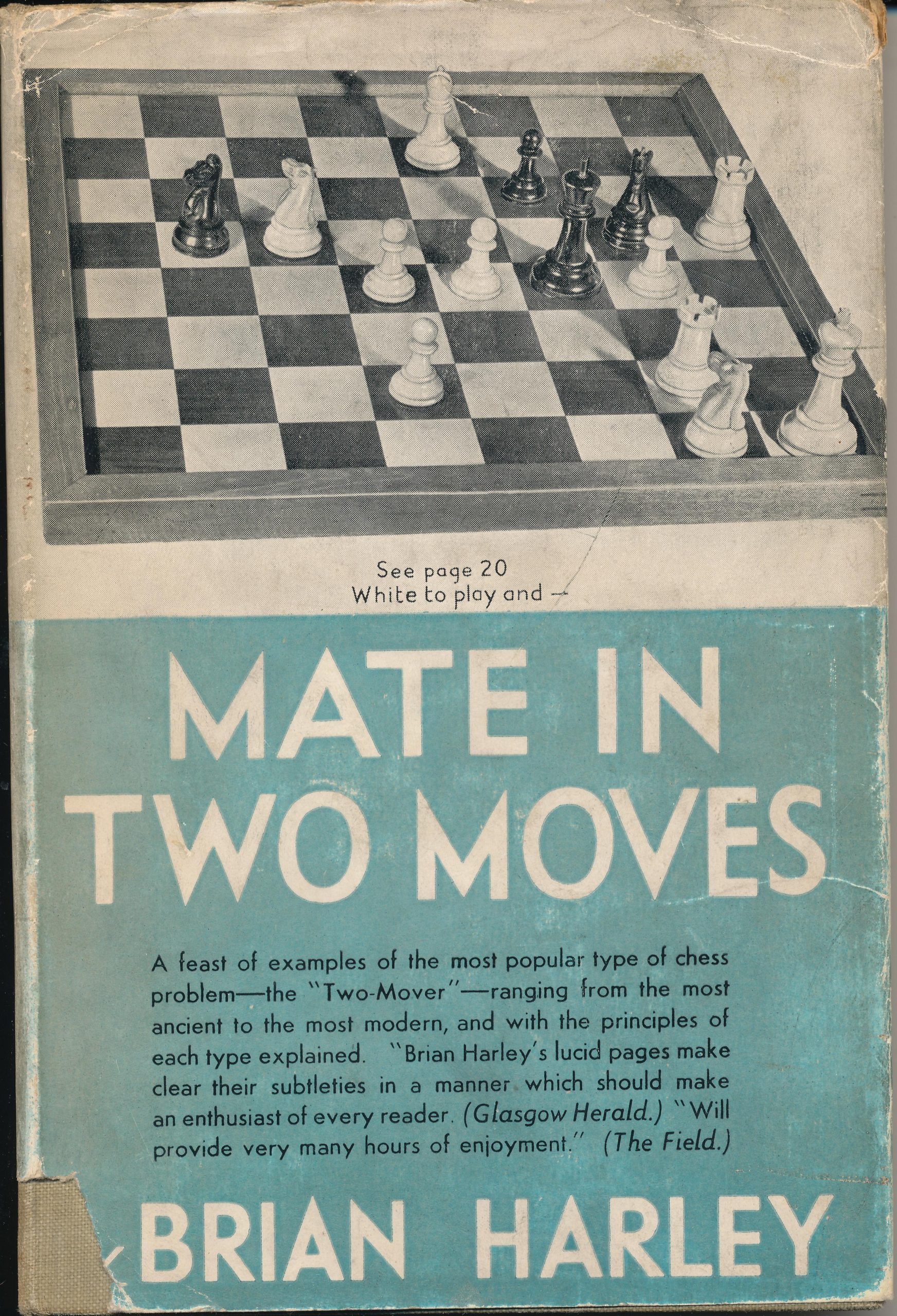

His contribution to the literary and technical side of chess problems outside his journalistic work is seen in his two books Mate in Two (1931) and Mate in Three (1943).

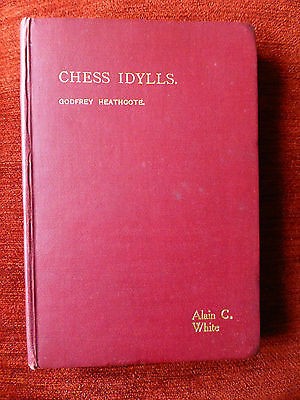

Mate in Two is stamped with all Harley’s inimitable style and remains a mine of information for all levels. Standing, as it does, mid-way between the old and the new, the book, apart from an absorbing chapter on changed play, reflects and even labours under the influence of the “Good Companion” period. Harley in later editions to a certain extent remedied this deficiency and the book, now long out of print, lies on our shelf, its fundamentals unimpaired, as one of the classic expositions in the art. Mate in Three, written from a’ narrower viewpoint, proved another successful publication. Here Harley entered more controversial ground, crossing swords. with hitherto established theory. The book, although not evoking absolute technical authority, gives a broad and eloquent outline, written from the artistic standpoint, of three-move work fundamentally, with few significant omissions. Made memorable by the inclusion of many works both by Harley and Heathcote, the book is that of a true artist, and is of great importance theoretically as the one modern work devoted to this length by an English author.

A further important contribution to chess problem theory was his thesis on “Black Correction” read before the British Chess Problem Society on November 29th, 1935. In the mid thirties, this thesis, more than anything else, was instrumental in precipitating a flood of work on correction and associated ideas. Readers of this magazine will recall this period, and I trust that this short recapitulation will still the tiresome arguments regarding the choice between “correction” and “continued defences.” Harley’s choice is at once apt and descriptive and it should not be forgotten that here, he touched upon White Correction, an esoteric aristocrat, greeted by ten years or so of utter silence before systematic investigation by the moderns.

Elected President of the British Chess Problem Society in 1947-1949 it so happened that I was its Secretary at the time. We exchanged hundreds of letters on problematic subjects, the scope of his knowledge always affording surprise. The Society benefited enormously from his advice and counsel, and during the somewhat delicate situation arising from the arbitration in the two-move section of the 1948 Olympic Tourney it was with alacrity that one turned to a mind of the calibre of Harley. Coming to the man he was widely read, a Latin scholar, and his knowledge of Dickens was above average; a keen bridge player, an instrumentalist (piano), all the varied facets of his character would come out at some time in his chess writings. His physical presence at any gathering gave it stature. Of medium height, lovable, somewhat dapper, the shrewd contemplative face of this chess Barrie with its ever present cigarette holder and fund of anecdote has enriched and enlivened many a dull Committee Meeting.

On the death of Anthony Guest in 1925, Harley succeeded as Problem Editor of the Morning Post until 1932. In addition he was Problem Editor of Empire Review, 1923-1926, and Time and Tide, from 1951 until his death. Lesser appointments included several technical journals where he acted under pseudonyms. Amusing were the anagrammatical pseudonyms used occasionally for composing in Hilary Bream and Harry Blaine.

Brian’s integrity and character endeared him to innumerable correspondents and solvers. Most of us nourish a characteristic Brian Harley story; one must suffice here. It concerns the time when Brian was introduced to the late Sir John Simon who made the delightful response “l need no introduction for I meet him every Sunday and for years hive wrestled with his problems, eventually solving them in the House of Commons.” For this weekly enrichment of our lives we have much to thank him for.

In middle life Brian married Ella Margaret Beddall; there is one son, Nigel. With his wife, Brian shared many problematic triumphs and it was to her that his various books were dedicated.

Before closing this brief review of Brian’s achievements a word should be said regarding the summary end of his work in the Observer and a tribute paid by one of his many solvers in this column. On the former it will be regarded with universal regret by all problemists that no arrangements have been made to continue Brian’s incomparable work in the journal he served with such distinction. Regarding the latter am very grateful to Halford W. L. Reddish, Esq., for an appreciation that admirably epitomizes the feelings of us all on this melancholy occasion.

Mr. Halford Reddish writes-

“l am one of thousands of solvers, from the expert to the merest tyro, who will miss our weekly battle with Brian Harley in the Observer. In the world of chess and chess problems his name and fame are secure. His characteristically titled Chess for the Fun of It is a delightful exposition of the game: his Mate in Two Moves and Mate in Three Moves are classics in their particular field.

To those of us who knew Brian personally his passing leaves an unfillable gap. I had known him and admired him and loved his witty, cheery, kindly personality for many years. He was one of those rare beings who became a close friend even before our first meeting-for we had corresponded for a long time before we first came face to face. And although chess and chess problems were our primary link he had many other interests which kept him young and keen in mind after his retirement from business and which enlarged and enriched his correspondence. It is typical of him that no letter came from him without some mention of his dear wife, who shared to the full his varied interests. To her and to his only son to the deep sympathy of his many friends.”

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977), Harry Golombek OBE, John Rice writes:

“British problemist, known perhaps less for his problems (mainly two- and three-movers) than for his influential writing and editing. Chess correspondent of the Observer for over twenty years. Books include: Mate in Two Moves (1931), Mate in Three Moves (1943), and published posthumously) The Modern Two-Move Chess Problem, with problems by C. Mansfield (1958), President of the British Chess Problem Society 1947-9″