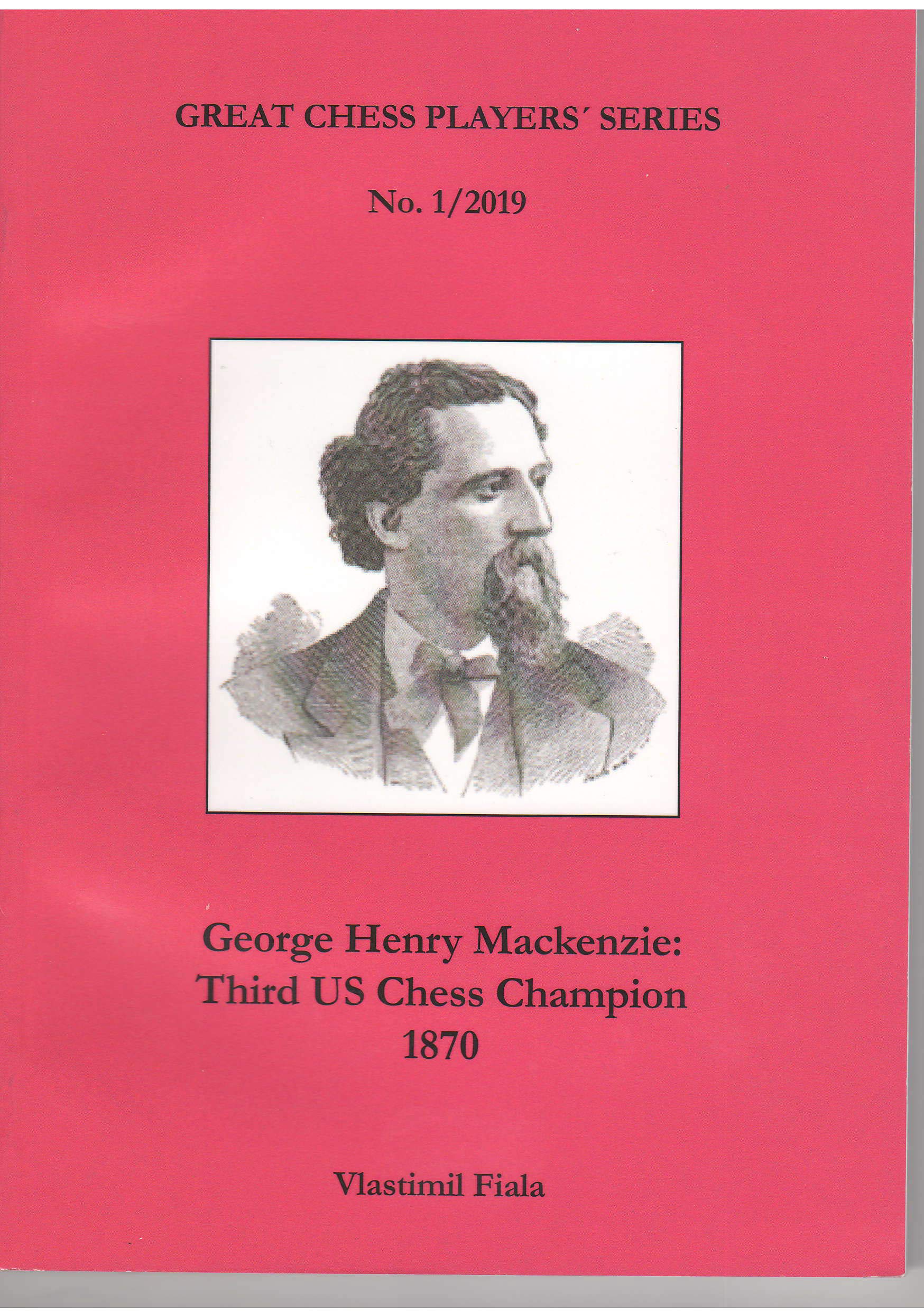

George Henry Mackenzie: Third US Chess Champion, 1870

From the publisher:

Definitive biography of the strongest American chess player, which cover the year 1870. Author worked out all available American (and other) chess sources for this year (The Turf, Field, and Farm, Sunday Mercury, New York Albion, New York Clipper, all New York dailies, British chess columns and European chess magazines, etc.) and collected in total 56 games played by Mackenzie in this year, almost of them are fully annotated. Author described in detail all chess tournaments and matches played by Mackenzie in 1870, including description of his all chess activities and New York chess life. 167pp. Indexes of players and openings.

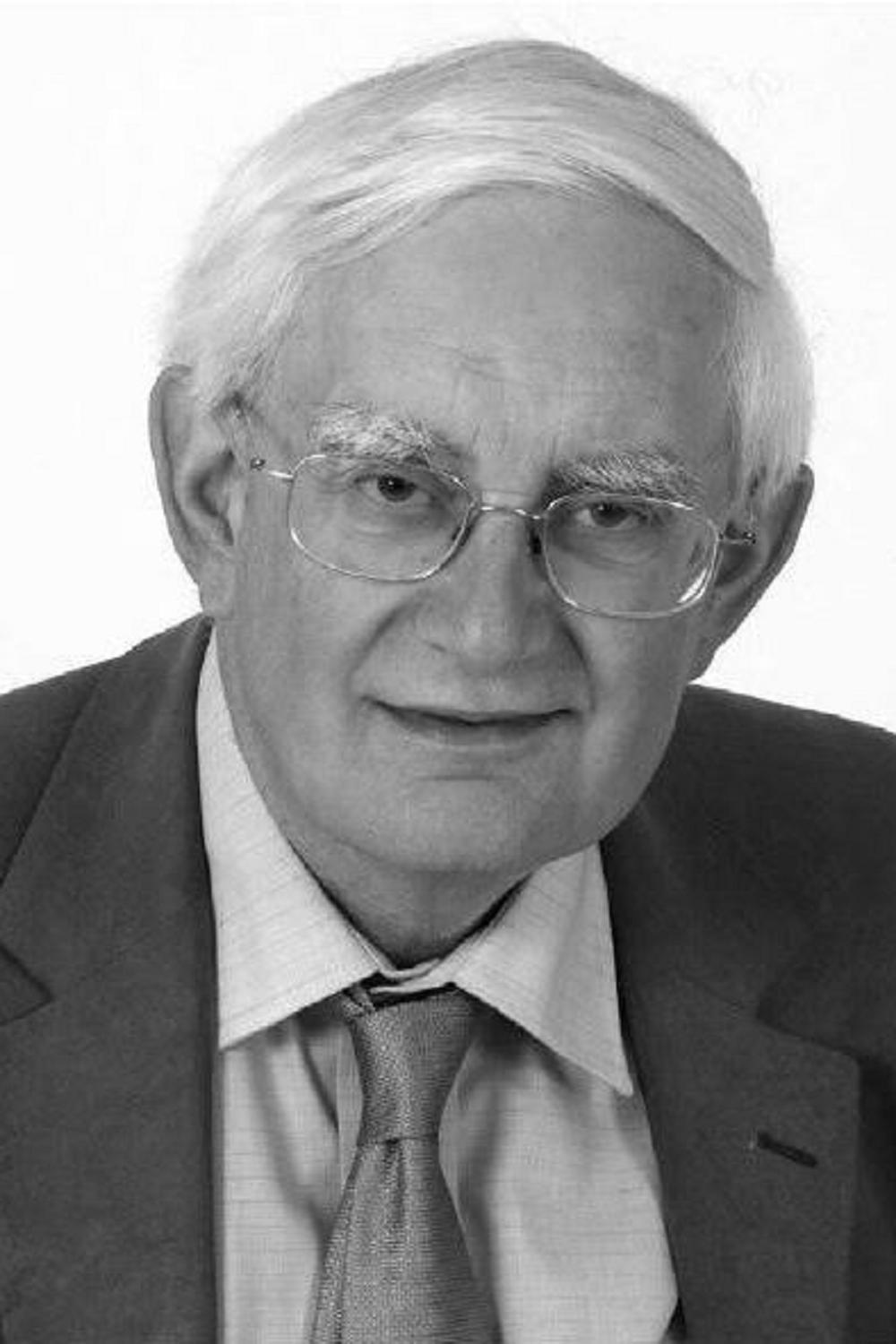

Vlastimil Fiala is a professor of Political Science and distinguished academic and the main driving force behind the publishing house, Moravian Chess based in Olomouc in the Czech Republic. Fiala’s second love is chess history which he treats as a science. His publication portfolio is impressive : the web site of Moravian Chess provides a listing.

Professor Fiala’s Moravian Chess publishing house have been bringing out a lot of valuable material for more than two decades now.

This volume, dated 2019 but seemingly only recently published, is the first of a new series.

The Foreword provides some explanation:

The lives of famous chess players (Paul Morphy, Wilhelm Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, Jose Raul Capablanca, Alexander Alekhine etc.) have by now been covered in dozens of publications of varying quality. Writing an exhaustive biography of professional chess players whose careers span multiple decades is a highly demanding task. When authors have attempted to do so, books containing a 700-900 A4 pages result (for instance several titles from MacFarland publishing house about A.A. Alekhine, A. Burn etc.), and these biographies moreover turn out to be less exhaustive than they first appear. Many details of their chess career are side-lined, or ignored entirely (e.g. chess exhibitions, consultation games, correspondence play, study composition, journalistic activities etc.). Their careers are usually not even contextualized into the wider, colourful canvas of chess events taking place in the same historical period.

You might think he’s being a bit hard on McFarland there, and not just for spelling their name incorrectly.

After considering all the options, I decided on an unconventional solution: the creation of the “Great Chess Players” series, which features biographies of prominent chess players centred on brief periods of time, usually a single year. In the years to come I want to focus on increasingly details (hopefully definitive) accounts of the careers of the following world chess champions: Paul Morphy, Wilhelm Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, José Raul Capablanca, Alexander Alekhine, and George Henry Mackenzie.

Well, it’s debatable whether or not you’d consider Morphy a world chess champion, even though he was undoubtedly the best player in the world for a few brief years, but Mackenzie?

Let’s not be too critical, though. Fiala seems to be a one man band working in what is (at best) his second language and performs a vital service for chess historians with both reprints and original research.

He takes a completist approach to history: publishing everything written about his subject in the year in question, as well as every published game. It’s by no means the only approach to writing chess history, or, indeed, any sort of history. Contextualisation, as Fiala says, is important, but completism is not the only way to contextualise.

As the prequels have not yet been published, some background information on Mackenzie might be in order.

George Henry Mackenzie was born in Scotland in 1837 and learnt chess in his teens. Originally destined for a business career, he instead decided to join the army, seeing service in South Africa and India. He then crossed the Atlantic to fight for the North in the American Civil War, reaching the rank of Captain but ending up in prison for impressment and desertion. On his release in 1865 he exchanged the battlefield for the chequered board, settling in New York to make a living as a chess professional, playing games against all-comers, organising clubs and tournaments, and writing newspaper columns. It soon became clear that, apart from Morphy, he was the strongest player in his adopted country, but, as we meet him for the first time seeing in the New Year at the Europa Chess Rooms, there had been little opportunity for him to take on top level opposition.

Morphy’s brief career had led to an increase in the popularity of chess, and New York was generally regarded as the home of most of the country’s strongest players. As we follow Mackenzie round the city’s chess clubs we learn a lot about how chess was played and organised at the time. Our hero was at the heart of everything going on, as player, journalist and organiser, and we can observe how chess was developing into the competitive activity we know today.

We have in total 56 games played by Mackenzie, with annotations taken from contemporary newspapers. No attempt has been made to update them with engine analysis: you might or might not approve. Given their nature, it’s not really a problem for me. Many of them are either odds games or consultation games: both of these were very popular at the time. Over the next decade or two they would gradually die out, to be replaced by a programme of tournament and match chess.

Here, for example, is Mackenzie giving odds of pawn and two moves to Augustus Zerega. These were common odds at the time: the odds giver takes the black pieces, plays without his f-pawn and allows his opponent to play the first two moves.

The highlight of early 1870 was the Brooklyn Chess Club championship, which included, apart from Mackenzie, a young James Mason, as well as names such as Eugene Delmar and Frederick Perrin, who might be familiar to those interested in chess history. It was run as an incomplete double-round all-play-all tournament with about 26 participants. You could choose who you played and when you played them. Mackenzie finished with 31 wins and 2 losses, just ahead of F Eugene Brenzinger. Eight of his games have survived, and are given here.

In May Mackenzie played a match against Perrin, comprising four games on equal terms and four where Mackenzie gave odds of pawn and move (he played black and started without his f-pawn). Perrin held his opponent to a draw on level terms in the first game, but that was all he was able to score. Five of the games have survived.

The chess year continued with a mix of offhand, odds and consultation games, enlivened by a visit from two of Chicago’s leading players. In August the Brooklyn club decided to play a consultation game to find out whether a queen could beat eight pawns. Yes, it could.

But the most significant event of the summer months was an inter-club match between the Café International in New York (Mackenzie was its chess manager) and the Brooklyn Chess Club. Up to that point competitions between clubs had usually been consultation matches, but this was what we’d now consider a Scheveningen System tournament, but with some irregularities. Six rounds were due to be played, with six players on each side, and with each player facing a different opponent in each round. In fact, only five rounds were played as, by that time, the Café International had opened up an unassailable lead, and, in the fifth round there were only five players on each side.

Not everyone was available for each round so, in the end, eight players on each side took part.

A controversy arose as early as the second round, when the Café International fielded a ringer in the shape of Mackenzie’s Bostonian friend Preston Ware. Frederick Perrin was unimpressed. “Although happy at all times to meet so agreeable and accomplished a chess-player as Mr. Ware, we regretted that the Brooklyn players allowed this substitution. To allow substitutes when New York possesses such an array of chess-players, and the Brooklyn Chess Club comparatively so few, must be very prejudicial to the success of the latter, and to admit one of the very best players of Boston into their ranks looks very much like a practical joke on the Brooklynites.”

Just the sort of dispute that has plagued club chess competitions ever since. We’ve all been there.

Only one of Mackenzie’s games from this event is available:

Autumn 1870 witnessed another competition between the Café International and Brooklyn Chess Club: this time a series of 12 consultation games, with the New Yorkers running out narrow winners. Mackenzie was on the wrong side of two of the games. The results and games in the book don’t quite tally, though. It looks like the results of the 5th and11th games are the wrong way round.

But much of Mackenzie’s work in the last months of 1870 was administrative: setting up a chess congress for the following year.

There, at the end of 1870, we leave Mackenzie, at least for this volume. It’s not clear at the moment when the sequel will be published, but, of course, you’ll want to know what happened next.

The 1871 American Congress eventually took place in Cleveland the following December, with Mackenzie winning comfortably. He continued his rabbit-bashing career in New York until 1878, when, at the age of 41, he was invited to his first major international tournament, in Paris. He performed respectably, sharing 4th place with Bird, behind Zukertort, Winawer and Blackburne. His next major event was Vienna 1882, and, for the rest of the decade, he was a regular visitor to the top table. He scored his best result at the age of 50, winning at Frankfurt in 1887. His last tournament was Manchester 1890, but by then he was suffering from tuberculosis, and he died the following year.

He was clearly one of the world’s strongest players for the last 25 years or so of his life, but, living the wrong side of the Atlantic, he had, for many years, to content himself with acting the flat-track bully, along with his involvement in other aspects of chess.

An important, but not very well documented historical figure, then, who led an interesting life. It’s good to know that John Hilbert is working on a full biography for McFarland. I’m certainly eager to find out more about his military career.

If you’re interested in chess history you’ll find this well worth reading to give you an idea of how chess was played and organised a century and a half ago. From a personal perspective – and you might well disagree – I’d have preferred less detail on administrative issues, tournament regulations, committee meetings and so on, and more background information.

How did Mackenzie’s life work financially? Was he well off or struggling to make a living? How did he get paid? We all know about the Blackburne Shilling Gambit, so I guess many of his opponents were paying for the privilege of playing him. I suppose this information isn’t readily available, though.

Who were his opponents? What sort of person was attracted to the New York chess clubs at that time? Augustus Zerega, for instance, was seriously wealthy, having made a fortune as a shipping magnate. Eugene Brenzinger, by contrast, was a German-born baker, renowned for his delicious cakes. Napoleon Marache, born in France, most famous for losing a Famous Game to Morphy, was a problemist, editor and writer.

Perhaps there are lessons we can learn as well. There’s much talk, at least in chess clubs in my part of the world, about doing more to promote social chess. Perhaps we might consider reviving activities such as odds games and consultation matches in order to bring our clubs’ first team players together with their lower rated clubmates.

The production is serviceable, but, understandably, not up to the quality you’d expect from McFarland, for example. The project of which this is the first part, is extremely ambitious: perhaps too much so, but we’ll have to wait and see. I wish Professor Fiala every success in adding to his already extensive contribution to chess history. If you’d like to support him you know what to do.

Richard James, Twickenham 9th May 2021

Book Details :

- Softback : 168 pages

- Publisher: Publishing House Moravian Chess; 1870th edition (1 Jan. 2019)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:8071890189

- ISBN-13:978-8071890188

Official web site of Moravian Chess