BCN remembers Johann Löwenthal (15-vii-1810 24-vii-1876)

A biography written by Thomas Seccombe, revised by Julian Lock appears in The Oxford Dictionary for National Biography.

BCN remembers Johann Löwenthal (15-vii-1810 24-vii-1876)

A biography written by Thomas Seccombe, revised by Julian Lock appears in The Oxford Dictionary for National Biography.

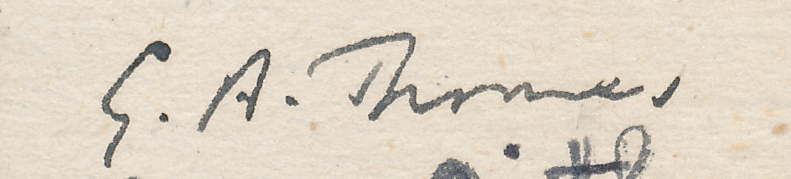

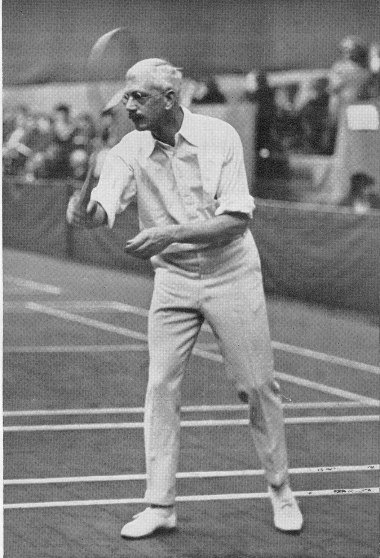

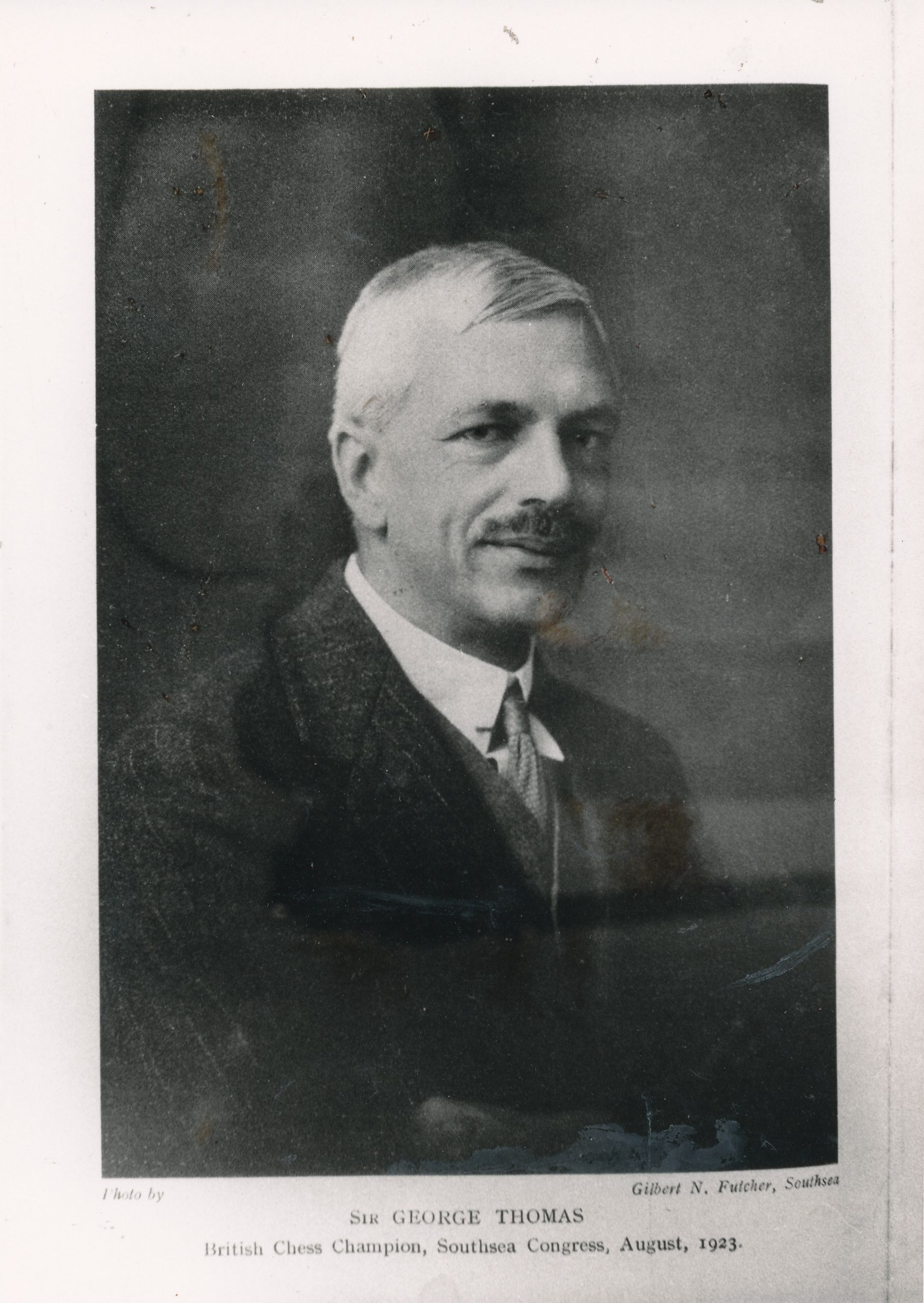

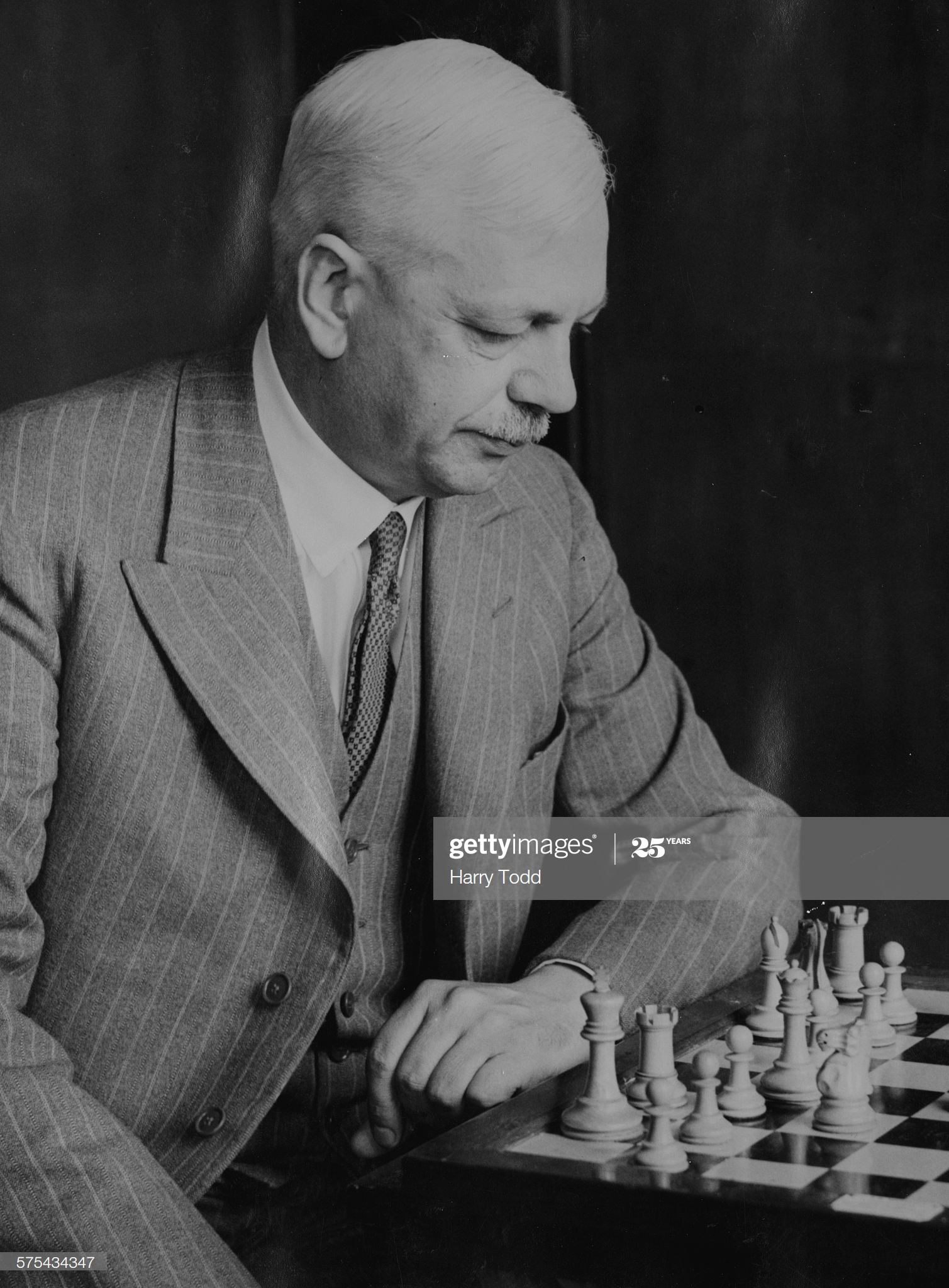

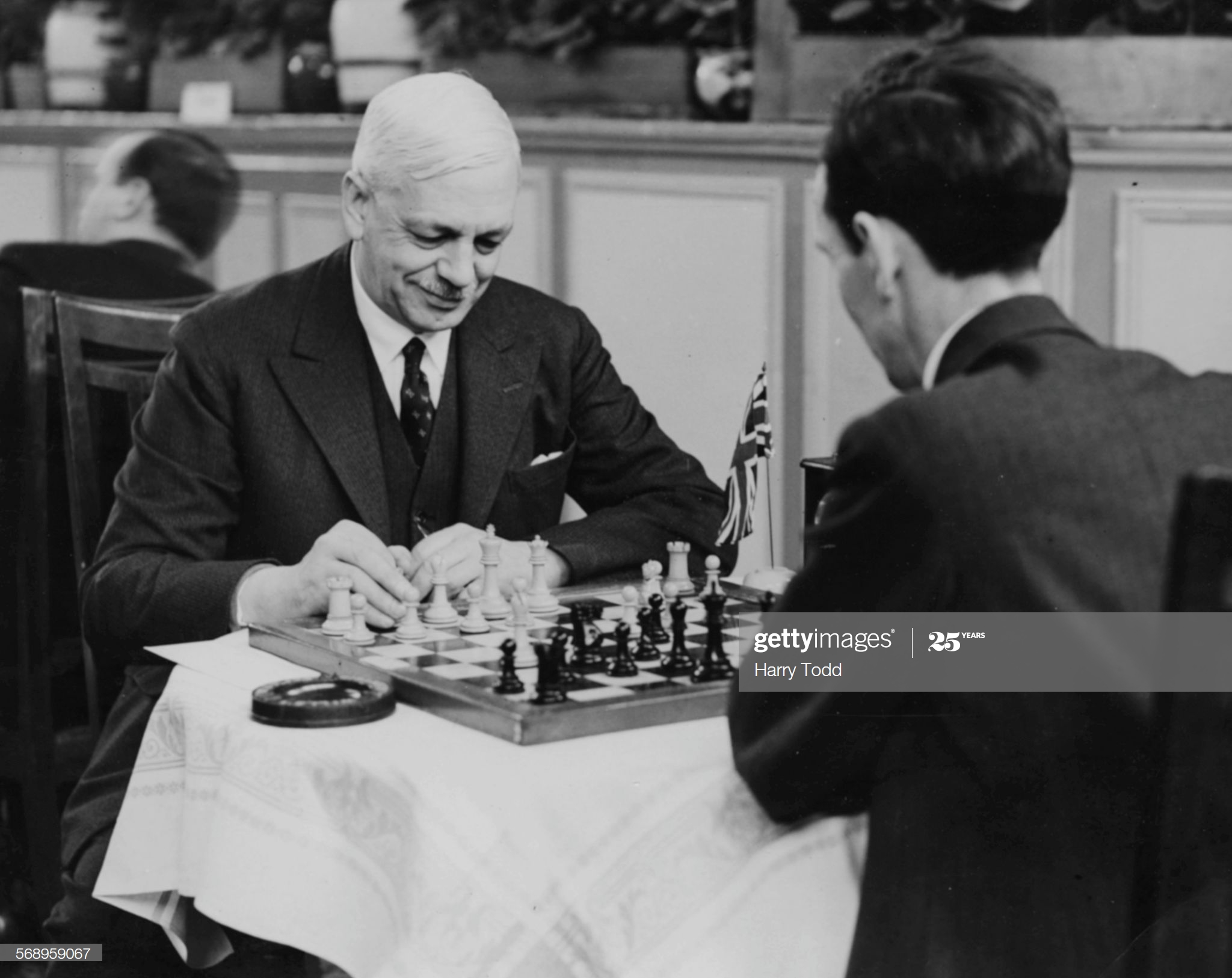

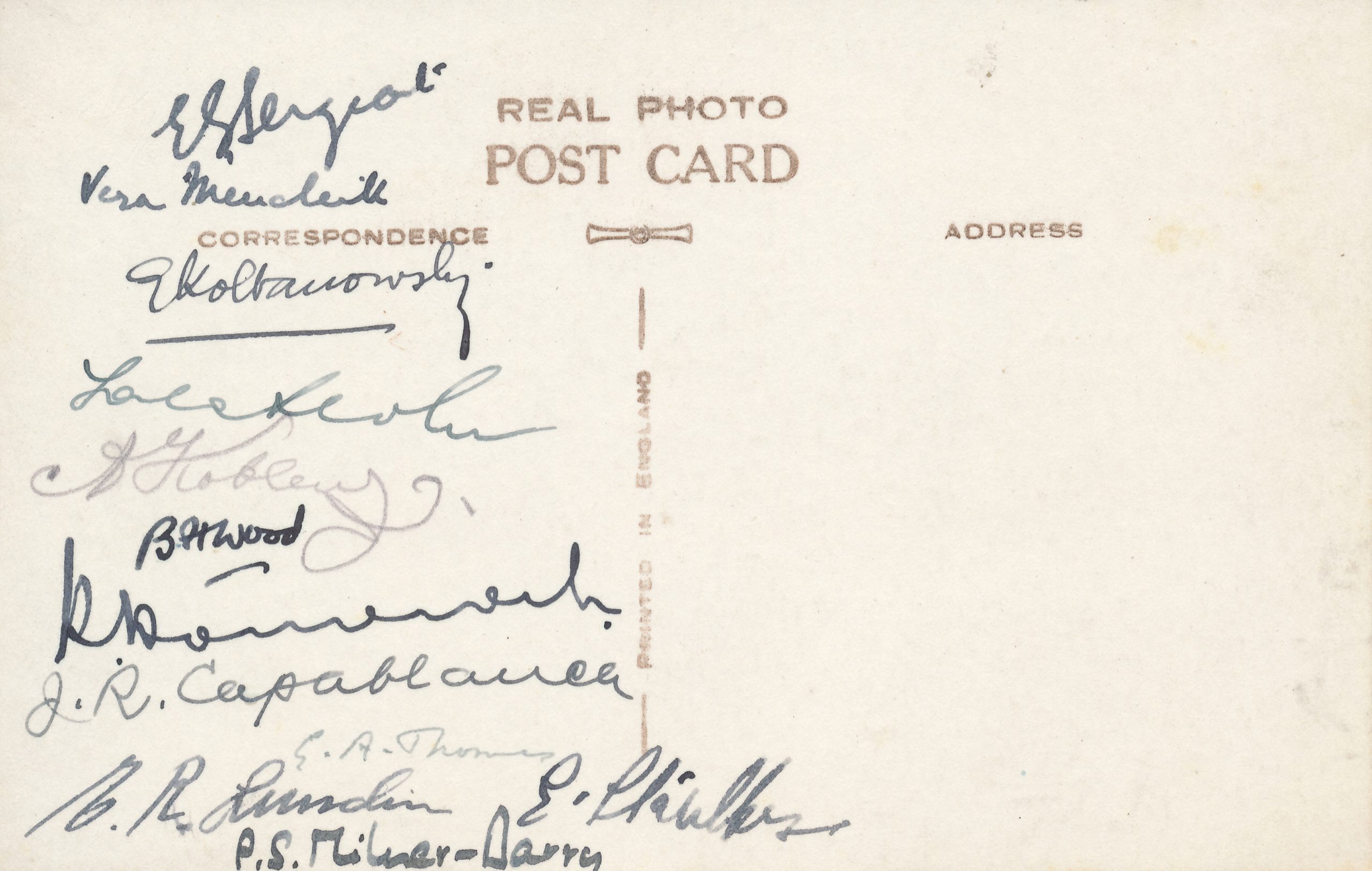

We remember Sir George Alan Thomas who died on July 23rd, 1972

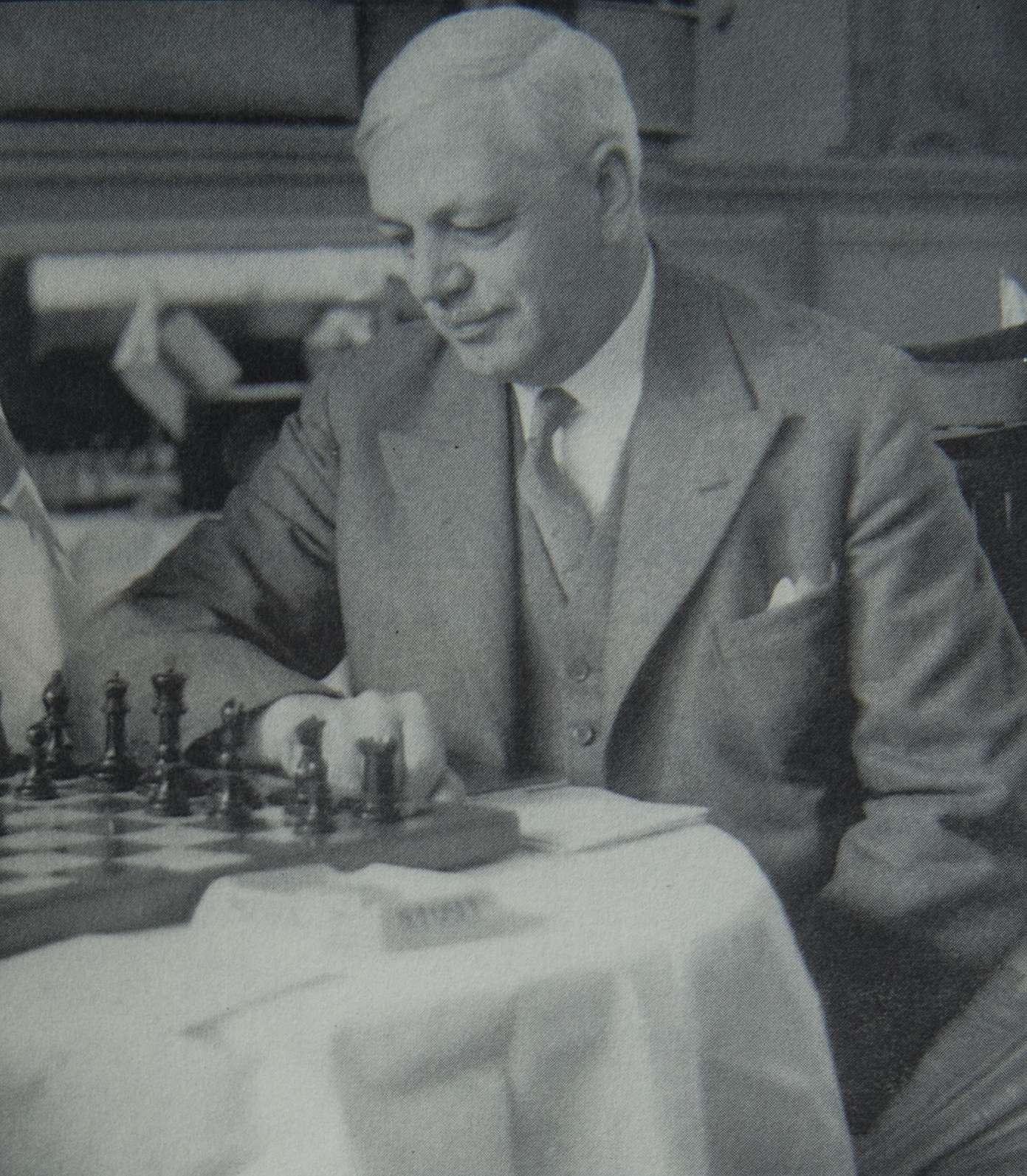

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (BT Batsford, 1977) by Harry Golombek :

“British international master, born in Constantinople (previously Byzantium and currently Istanbul : Ed.) His mother (Lady Edith Margaret Thomas : Ed) was one of the strongest English women players, winner of the first Ladies tournament at Hastings 1895.

(Ed : his father was Sir George Sydney Meade Thomas)

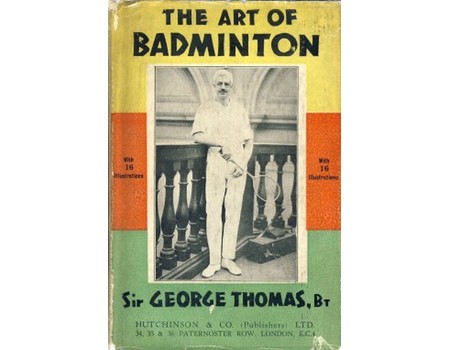

Thomas was an all-round athlete who excelled at tennis, hockey and badminton as well as chess. He captained the English badminton team and was All England Badminton Singles champion from 1920 to 1923.”

Here is an excellent article (albeit stating GT was a Grandmaster and was president of the British Chest Federation!) from the National Badminton Museum.

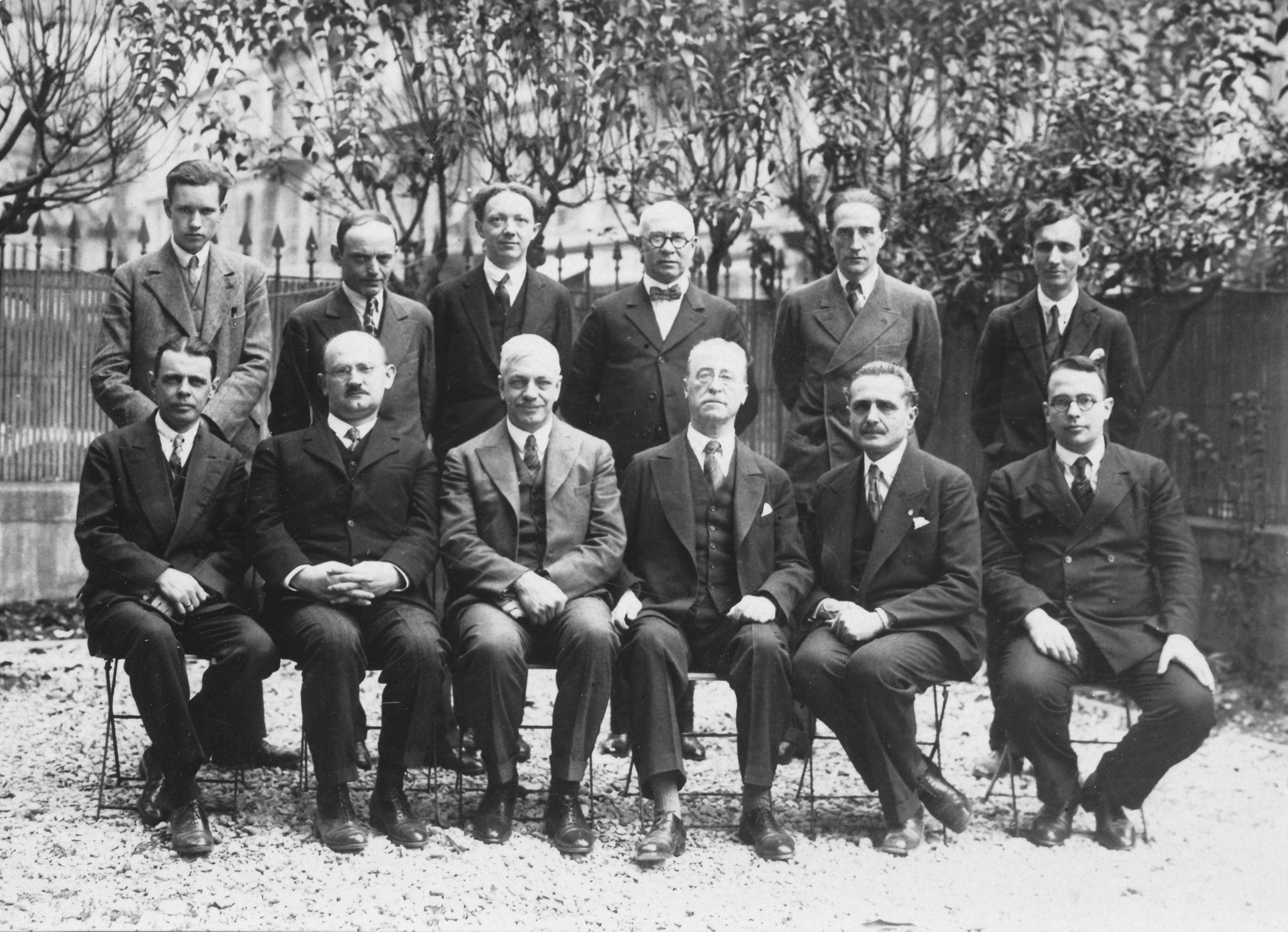

“Thomas won the British chess championship twice, in 1923 and 1934 and represented England in the Olympiads of 1927 where he tied with Norman Hansen for the best score – 80% on board 3, 1930, 1931, 1935, 1937 and 1939.

In international tournaments his greatest successes were 1st at Spa (ahead of Tartakower) and =1st at Hastings 1934/5 (tied with Euwe and Flohr, ahead of Capablanca and Botvinnik).

He was known for his keen sense of sportsmanship and for his ability to encourage and inspire younger players. He served for many years on the BCF Junior selection committee and was for a time Games Editor of the British Chess Magazine. FIDE awarded him the titles of international master (1950) and International Judge (1952). (article by Ray Keene)”

Thomas with the White pieces was predominantly a Ruy Lopez devotee.

With the Black pieces against 1.e4 he defended the Lopez and the Queen’s Gambit Declined was his favourite versus 1.d4

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (Robert Hale 1972 and 1976) by Anne Sunnucks :

“International Master (1950), International Judge (1952) and British Champion in 1923 and 1934. All England Badminton Singles Champion, All England Badminton Doubles Champion, Wimbledon tennis player and county hockey player.

Sir George Thomas was born in Constantinople on 14th June 1881. His mother, Lady Thomas, won the first ever ladies’ tournament, which was held in conjunction with the Hastings International Chess Tournament of 1895.

He learned the moves at the age of 4, and as a boy met many of the world’s leading players, including Steinitz, Lasker, Tchigorin and Pillsbury, in his mother’s drawing-room.

Apart from serving as a subaltern in the Army during the 1914-1918 war, Sir George has devoted his life to sport. He played tennis at Wimbledon, played hockey for Hampshire, captained the English Badminton team and was All England Badminton Singles Champion from 1920-1923 and doubles champion nine times.

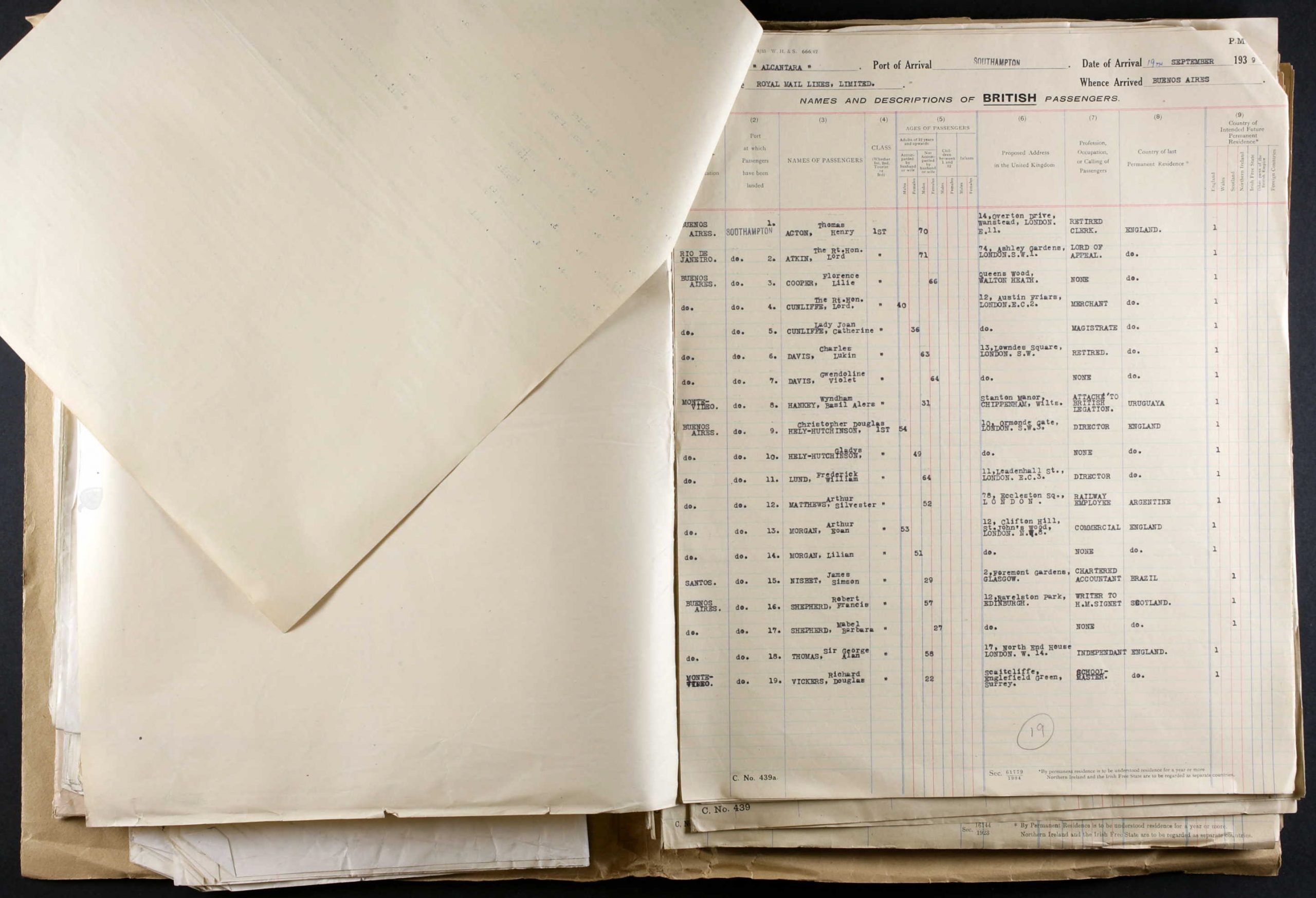

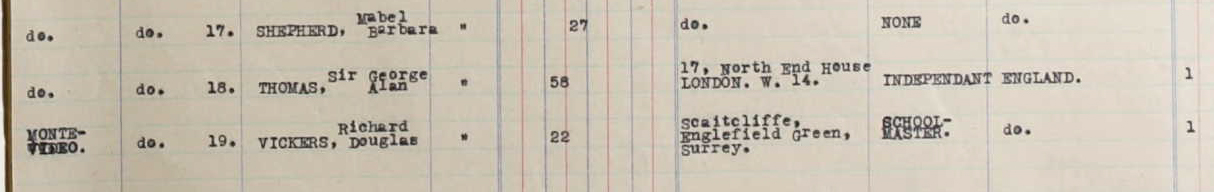

Sir George played chess for England regularly from 1910 to 1939. He played for the British Chess Federation in the Chess Olympiads of 1927,1930, 1931, 1933, 1935, 1937 and 1939, and captained the team which withdrew from the Buenos Aires Olympiad in 1939 on the out-break of war.

His first appearance in the British Championship was in he came 2nd. He also came 2nd in 192l and in 1923 won the first time, thus becoming British Chess Champion and Badminton Champion in the same year.

Sir George’s best performance was at Hastings 1934-1935, when he came =1st. In the last round he needed only a draw against R. P. Michell to come lst, ahead of Euwe, Capablanca, Flohr and Lilienthal, but he lost and had to be content with sharing lst prize with Euwe and Flohr.

During his career he has beaten Capablanca, Botvinnik (in consecutive rounds at Hastings 1934-35), Flohr and and drawn with Nimzowitsch, Rubinstein and Capablanca. He been noted for his sportsmanship and for his interest in and encouragement of young players.

Since his retirement until the last few years, Sir George continued to attend tournaments as a spectator.

He is the author of The Art of Badminton, published in 1923.

He died on 23rd July 1972 in a London nursing home.”

In the March issue of CHESS for 1963, (Volume 28, Number 427, pp.147-155) William Winter wrote this:

Another great figure of the period between the wars, Sir G. A. Thomas, is happily still with us, although he gave up competitive play some years ago. I think I must have played more games with him than with any other master and he was my principal rival in the battles for the British Championship which we each won twice.

Although he lacks Yates’ spark of genius he is a very fine player indeed and one of the few Englishmen who is a real master of the endgame. Both nationally and internationally he has an excellent record, probably the best of a number of performances being his tie with Euwe and Flohr for lst prize at Hastings 1934-5. Capablanca and Botvinnik were among the also-rans. Thomas beat both of them, a splendid performance when we consider the small number of games ever lost by either. He is the only native Englishman to have scored a win over Capablanca. He acted as captain of all the British teams of which I formed part and an excellent leader he made, firm when necessary, but always considerate to his men especially when they were doing badly.

Sir Thomas, as he was called, is much missed on the Continent where he was highly popular and did a great deal to increase the prestige of British chess.

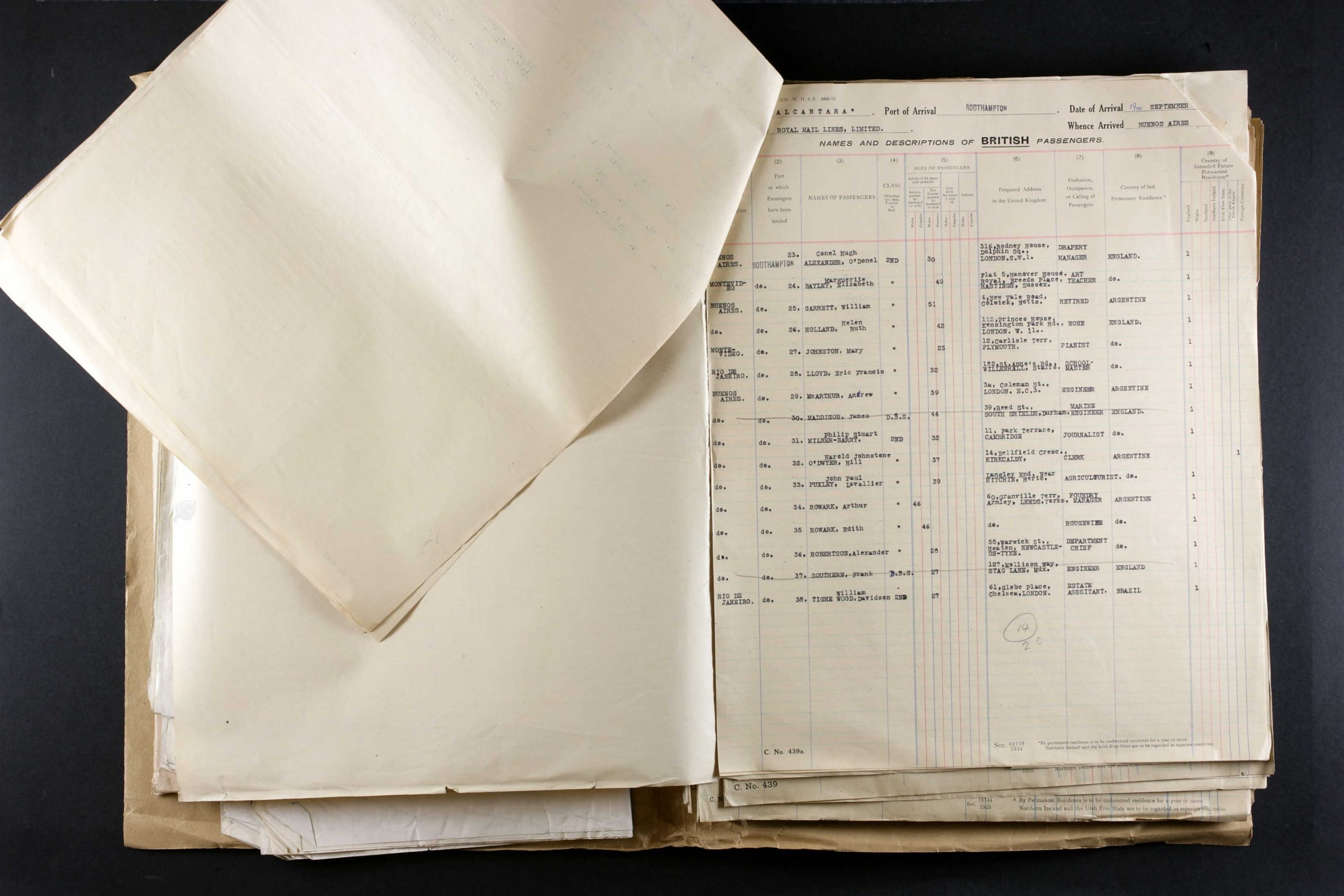

Here is Part II of GM Matthew Sadler’s appreciation of Sir George.

Most interestingly we have this this splendid article from Neil Blackburn (SimaginFan) on chess.com

Here is his Wikipedia entry

and here is Part III of Matthew Sadler’s article

From The Oxford Companion to Chess (OUP, 1984) by Hooper & Whyld :

“English player. International Master (1950), International Arbiter (1952), British champion 1923 and 1934. His mother, who taught him chess, was winner of one of the first women’s tournaments, Hastings 1895, He played in more than 80 tournaments and achieved his best result at Hastings 1934-5 (about category 9), when he scored +6-1—2 to share first prize with Euwe and Flohr ahead of Botvinnik and Capablanca. Thomas played in seven Olympiads from 1927 to 1939, and in the first the highest percentage score was made by him ( + 9=6) and the Dane Holgar Norman-Hansen (1899- ) (+11=2—2). A leading English player for more than 25 years, Thomas fought many battles at the famous City of London club, winning 16 of the annual championships from 1913-14 to 1938-9. In his sixty-ninth year he gave up competitive chess when, after a hard game, ‘the board and men began to swim before my eyes,’ He continued his active interest in junior events and his visits, now as a spectator, to chess events.

A man of few words, imperturbable, of fine manners. Sir George Thomas was respected throughout the chess world for his sportsmanship and impartiality, and his opinion was often sought when disputes arose between players. The inheritor of both a baronetcy and private means, he

devoted his life to games and sports. Besides his chess he was a keen hockey player, a competitor in international lawn tennis (reaching the last eight at Wimbledon on one occasion), and winner of about 90 badminton titles, notably the All-England men’s singles championship which he won four times, from 1920 to 1923.”

Bill Hartston wrote this in “On the Knight Shift”, Chapter 20 of the The Chess Player’s Bedside Book (Batsford, 1975) :

“In the days when chess was perhaps a more noble pastime, one of England’s leading players was the Baronet, Sir George Thomas. A true gentleman and sportsman, he considered it rather unprincipled to analyse adjourned games before their resumption and could only be persuaded to look at his own positions after being assured that his opponents were certainly taking full advantage of the adjournment in this manner.”

A biography written by Harry Golombek and revised by Margaret Whitehead appears in The Oxford Dictionary for National Biography (ODNB)

BCN remembers Howard Staunton (??-iv-1810 22-vi-1874)

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper and Whyld :

The world’s leading player in the 1840s, founder of a school of chess, promoter of the world’s first international chess tournament, chess columnist and author, Shakespearian scholar. Nothing is known for certain about Staunton’s life before 1836, when his name appears as a subscriber to Greenwood Walkers Selection of Games at Chess , actually played in London, by the late Alexander McDonnell Esq. He states that he was born in Westmorland in the spring of 1810, that his father’s name was William, that he acted with Edmund Kean, taking the part of Lorenzo in The Merchant of Venice, that he spent some time at Oxford (but not at the university) and came to London around 1836. Other sources suggest that as a young man he inherited a small legacy, married, and soon spent the money.

He is supposed to have been brought up by his mother, his father having left home or died. He never contradicted the suggestion that he was the natural son of the fifth Earl of Carlisle, a relationship that might account for his forename, for the Earl’s family name was Howard: but the story is almost certainly untrue, not least because in all probability Howard Staunton was not his real name. A contemporary, Charles Tomlinson (18O8- 97), writes: ‘Rumour . . . assigned a different name to our hero [Staunton] when he first appeared as an actor and next as a chess amateur.

At the unusually late age of 26 Staunton became ambitious to succeed at chess; a keen patriot, his motivation may in part have sprung from a desire to avenge McDonnell’s defeat at the hands of a Frenchman. A rook player in 1836 (his own assessment), Staunton rose to the top in a mere seven years. In 1838 he played a long series of games with W. D. Evans and a match of 21 games with Alexandre in which he suffered ‘mortifying defeat’ during the early sittings; but he continued to study and to practise with great determination.

In 1840 he was strong enough to defeat H. W. Popert, a leading German player then resident in London. In the same year he began writing about the game. A short-lived column in the New Court Gazette began in May and ended in Dec. because, says G. Walker, there were ‘complaints of an overdose’. More successful was his work for the British Miscellany which in 1841 became the Chess Player’s Chronicle, England’s first successful chess magazine, edited by Staunton until 1854, Throughout 1842 Staunton played several hundred games with John Cochrane, then on leave from India, a

valuable experience for them both.

In 1843 the leading French player Saint-Amant visited London and defeated Staunton in a short contest -(+3 = 1—2), an event that attracted little attention; but later that year these two masters met in a historic encounter lasting from 14 Nov. to 20 Dec. This took place before large audiences in the famous Café de la Régence. Staunton’s decisive victory ( + 11 = 4—6) marked the end of French chess supremacy, an end that was sudden, complete, and long-lasting.

From then until the 1870s London became the world’s chess centre. In Oct. 1844 Staunton travelled to Paris for a return match, but before play could begin he became seriously ill with pneumonia and the match was cancelled.

Unwell for some months afterwards, he never fully recovered: his heart was permanently weakened. In Feb. 1845 he began the most important of his journalistic tasks, one that he continued until his death: in the Illustrated London News he conducted the world’s most influential chess column. Each week he dealt with a hundred or more letters; each week he published one or more problems, the best of the time. In 1845 he conceded odds of pawn and two moves and defeated several of his countrymen and in 1846 he won two matches playing level: Horwitz (+14=3 — 7) and Harrwitz (+ 7). In 1847 Staunton published his most famous chess book, the Chess Player’s Handbook, from which many generations of English-speaking players learned the rudiments of the game: the last of 21 editions was published in 1939. He published the Chess Players Companion in 1849.

In 1851 Staunton organized the world’s first international tournament, held in London. He also played in it, an unwise decision for one burdened with the chore of organization at the same time. After defeating Horwitz (+4=1—2) in the second round he lost to Anderssen, the eventual winner.

Moreover he was defeated by Williams, his erstwhile disciple, in the play-off for places. Later that year Staunton defeated Jaenlsch ( + 7=1 — 2) and scored +6 = 1—4 against Williams, but lost this match because he had conceded his opponent three

games’ start. In 1852 Staunton published The Chess Tournament, an excellent account of this first international gathering. Subsequently he unsuccessfully attempted to arrange a match with Anderssen, but for all practical purposes he retired from the game at this time.

Among his many chess activities Staunton had long sought standardization of the laws of chess and, as England’s representative, he crossed to Brussels in 1853 to discuss the laws with Lasa, Germany’s leading chess authority. Little progress was made at this time, but the laws adopted by FIDE in 1929 are substantially in accordance with Staunton’s views. This trip was also the occasion of an informal match, broken off when the score stood +5=3-4 in Lasa’s favour. Staunton took the match seriously, successfully requesting his English friends to send him their latest analyses of the opening.

Staunton had married in 1849 and, recognizing his new responsibilities, he now sought an occupation less hazardous than that of a chess-player. In 1856. putting to use his knowledge of Elizabethan and Shakespearian drama, he obtained a contract to prepare an annotated edition of Shakespeare’s plays. This was published in monthly instalments from Nov. 1857 to May 1860, a work that ‘combined commonsense with exhaustive research’. (In 1860 the monthly parts ready for binding in three volumes were reissued, in 1864 a four-volume reprint without illustrations was printed, and in 1978 the original version was published in one volume.) Staunton, who performed this task in a remarkably short period, was unable to accept a challenge from Morphy in 1858: his publishers would not release him from his contract. After the proposal for a match was abandoned Frederick Milnes Edge (c. 1830-82), a journalist seeking copy, stirred up a quarrel casting Staunton as the villain. Morphy unwisely signed some letters drafted by Edge, while Staunton, continuously importuned by Edge, was once driven to make a true but impolitely worded comment about Morphy. Generally however these two great masters behaved honourably, each holding the other in high regard; but Edge’s insinuations unfairly blackened Staunton’s reputation.

Subsequently Staunton wrote several books, among them Chess Praxis (1860) and the Great Schools of England (1865), revised with many additions in 1869. At the end of his life he was working on another chess book when, seized by a heart attack, he died in his library chair.

Staunton was no one’s pupil: what he learned about chess he learned by himself. For the most part he played the usual openings of his time but he introduced several positional concepts. Some of these had been touched upon by Philidor, others were his own: the use of the ranch mo for strategic ends, the development of flank openings specially suited to pawn play. He may be regarded as the precursor of the hypermodern movement, the Staunton system the precursor of the Reti opening. In his Chess Players Companion Staunton remarks that after 1 e4 e5 Black’s game is embarrassed from the start, a remark anticipating Breyer’s ideas about the opening by more than half a century, Fischer wrote in 1964: “Staunton was the most profound opening analyst of all time. He was more theorist than player but none the less he was the strongest player of his day. Playing over his games I discover that they are completely modern.

Where Morphy and Steinitz rejected the fianchetto. Staunton embraced it. In addition he understood all the positional concepts which

modern players hold so dear, and thus with Steinitz must be considered the first modern player.

Tall, erect, broad-shouldered, with a leonine head, Staunton stood out among his fellows, walking like a king’. He dressed elegantly, even ostentatiously, a taste derived perhaps from his

background as an actor. G. A. Macdonnell describes him: “… wearing a lavender zephyr outside his frock coat. His appearance was slightly gaudy, his vest being an embroidered satin, and his scarf gold-sprigged with a double pin thrust in, the heads of which were connected by a glittering chain . . .’ A great raconteur, an excellent mimic who could entertain by his portrayals of Edmund Kean, Thackeray, and other celebrities he had met, he liked to hold the stage, ‘caring for no man’s anecdote but his own’. He could neither understand nor tolerate the acceptance of mediocrity, the failure of others to give of their best.

A man of determined opinions, he expressed them pontifically, brooking little opposition. Always outspoken, he often behaved, writes Potter, ‘with gross unfairness towards those whom he disliked, or from whom he suffered defeat, or whom he imagined to stand between himself and the sun’; ‘nevertheless’, he continues, ‘there was nothing

weak about him and he had a backbone that was never curved with fear of anyone.’ Widely disliked, Staunton was widely admired, a choice that would have been his preference. Reminiscing in 1897, Charles Edward Ranken (1828-1905) wrote: “With great defects he had great virtues; there was nothing mean, cringing, or small in his nature, and, taking all in all, England never had a more worthy

chess representative than Howard Staunton.

R. D. Keene and R. N. Coles Howard Staunton the English World Chess Champion (1975) contains biography, 78 games, and 20 parts of games.

The Staunton Defence has remained a completely playable gambit versus the Dutch Defence :

Here is his Wikipedia entry

A curious article about Staunton

A biography written by Sidney Lee, revised by Julian Lock for The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

From British Chess Magazine, Volume CXIX (119, 1999), Number 11 (November), page 584 :

“English Heritage unveiled a blue plaque to Howard Staunton, arguably Britain’s greatest 19th century chess player, in London on September 28. The unveiling took place at 117 Landsdowne Road, London W11, and was performed by Barry Martin, secretary of the Staunton Society, on behalf of English Heritage. Staunton lived with his wife at 117 Lansdowne Road between 1871 and 1874. He died at 27 Elgin Crescent later that year. The weather was favourable and a good crowd (including several grandmasters) was able to enjoy proceedings. BBC television covered the event for their lunch-time and evening news programme.”

BCN Remembers Johannes Hermann Zukertort (07-ix-1842 20-vi-1888)

From the July 2012 editorial in British Chess Magazine we had this report :

“Johann Hermann Zukertort’s (1842-1888) grave was rededicated last month in London’s crowded Brompton Cemetery, largely thanks to an initiative led by Stuart Conquest. The resting place of one of the leading players of the nineteenth century was recorded but the grave had fallen into terrible disrepair. See BCM 1888, pp.307-8 and p.338-340 for the obituary of the great man. We read that his death ‘was terribly sudden’, that he was buried on 26th June, 1888 and that ‘several pretty wreaths were laid on the coffin …’”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

Polish-born Jew, from about 1871 to 1886 second player in the world after Steinitz. From about 1862 to 1866 Zukertort, then living in Breslau, played many friendly games with Anderssen, at first receiving odds of a knight but soon meeting on even terms. They played two matches in Berlin, Zukertort losing the first in 1868 (+3 = 1—8) and winning the second in 1871 (+5 — 2).

In 1872 a group of London players, anxious to find someone who could defeat Steinitz, paid Zukertort 20 guineas to come to England. He came, he stayed, but he failed to beat Steinitz.

Zukertort took third place after Steinitz and Blackburne at London 1872, the strongest tournament in which He had yet played, and later in the year was decisively beaten by Steinitz in match play ( + 1=4—7). Zukertort settled in London as a professional player.

He won matches against Potter in 1872 ( + 4=8—2), Rosentalis in 1880 ( + 7=11-1), and Blackburne in 1881 ( + 7=5-2), He also had a fair record in tournament play: Leipzig 1877, second equal with Anderssen after L. Paulsen ahead of Winawer:-* Paris 1878, first ( + 14=5—3) equal with Winawer ahead of Blackburne (Zukertort won the play-off, +2=2); Berlin 1881, second alter Blackburne ahead of Winawer; and Vienna 1882, fourth equal with Mackenzie after Steinitz, Winawer, and Mason.

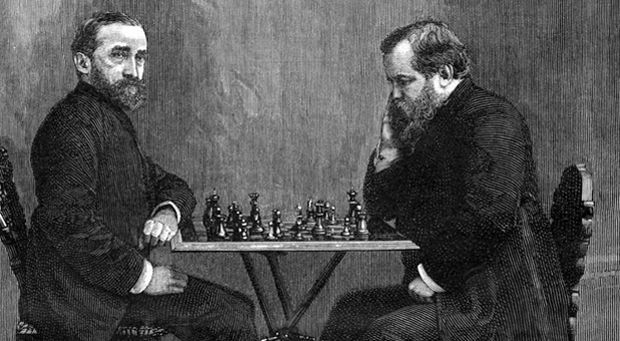

The world’s nine best players were among the competitors in the double-round London tournament of 1883 when Zukertort achieved his greatest victory: first prize (+22—4) three points ahead of Steinitz, the second prize winner, in seven weeks and a day he played 33 games (seven draws were replayed) and towards the end he relieved the strain by taking opiates, the cause of his losing his last three games. This victory led to the first match for the world championship, a struggle between him and Steinitz, USA, 1886. After nearly ten weeks of relentless pressure by his opponent Zukertort lost (- 1 – 5=5 —10) i winning only one of the last 15 games. His spirit crushed, his health failing, he was advised to give up competitive chess, but there was nothing else he could do. I am prepared, he said, l to be taken away at any moment.’ Seized by a stroke while playing at London’s famous coffee-house, Simpson’s Divan, he died the next day.

Like Anderssen, his teacher, Zukertort had a direct and straightforward style, and in combinative situations he could calculate far ahead. Having a prodigious memory he could recollect at will countless games and opening variations, a talent which may have limited his vision. (For his match with Steinitz in 1872 his extensive opening preparations brought him only one win. Steinitz was the better player in unfamiliar situations.) As an annotator and analyst Zukertort was outstanding in his time, and much of his work in these fields appeared in the Chess Monthly which he and Hoffer edited from 1879 to 1888.

Zukertort read widely and what he read became, as he said ‘iron-printed in my head’. Hoffer recalls Zukertort holding a visitor from India spellbound with a convincing and detailed account of a tiger-hunt, although it must have been outside his experience. Zukertort’s own account of his early life was reported in the Norfolk News, 16 Nov. 1872, He claimed aristocratic (Prussian and Polish) descent, and fluency in nine languages. “He learnt one language to read Dante, another to read Cervantes, and a third, Sanskrit, to trace the origin of chess,’ Besides the study of theology, philology, and social science he is also an original thinker on some of the problems that perplex humanity , ” He is ‘an accomplished swordsman, the best domino player in Berlin, one of the best whist players living, and so good a pistol shot that at fifteen paces he is morally certain to hit the ace of hearts . , , has found time to play 6,000 games of chess with Anderssen alone … a pupil of Moscheles, and in 1862-6 musical critic of the first journal in Silesia … is also a military veteran … he served in the Danish, in the Austrian, and in the French campaign , , , he was present at the following engagements, viz, in Denmark, Missunde, Duppcl, and Alsen; in Austria, Trauienau, Koniginhof, Kdniggratz (Sadowa), and Blumcnau; in France, Spicheeren, Pange (Vionville), Gravelotte, Noisevillc, and all other affairs before Metz, Twice dangerously wounded, and once left for dead upon the field, he is entitled to wear seven medals besides the orders of the Red Eagle and the Iron Cross, . . . He obtained the degree of M.D. at Breslau in 1865, having chiefly devoted his attention to chemistry under Professor Bunsen at Heidelberg, and to physiology at Berlin under Professor Virchow … is now on the staff of Prince Bismarck’s private organ, the Allgemeine Zetiling, and is chief editor of a political journal which receives “officios’” from the Government at Berlin. He is . . . the author of the Grosses Schach Handbuck and a Leitfaden , and , . . was for several years editor of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung. ’ There is some truth in the last sentence: he was co-author of the books, co-editor of the chess magazine.

A. Olson, J. H. Zukertort (1912) is a collection of 201 games with Swedish text.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks

“One of the leading players of the last century, Zukertort was born in Riga on 7th September 1842. His father was a Prussian and his mother a Pole. When he was 13, his family moved to Breslau. After studying chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, he obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University in 1865. He served as a doctor with the Prussian Army during his country’s wars against Denmark, Austria and France and was decorated for gallantry.

Zukertort was a man of many talents. He had a prodigious memory, and it was said that he never forgot a game he had played. He spoke 11 languages, and he was an excellent pistol shot and fencer but it was journalism and chess that he chose for a career.

Zukertort learned to play chess when he was 18, and two years later he met Anderssen and became his pupil. Within three years he had become one of the strongest players in North Germany. He first drew attention to himself as a blindfold simultaneous player. In 1868, he gave a simultaneous blindfold display against seven players in Berlin. This was his first blindfold performan@, and it was so successful that he gave several further performances, almost immediately increasing the number of his opponents to 12.

Between 1867 and 1871, he was joint editor with Anderssen of the Neue Berliner Schachzeityng. In 1871 he played a match against Anderssen, probably the second strongest player in the world at that time, and beat_him by 5-2. Following this victory, he was invited to take part in the 1872 London Tournament. He came 3rd and, probably because he was disappointed at his result, immediately challenged – the winner, Steinitz, to a match for the title of World Champion. Steinitz had claimed this title after his victory over Anderssen in 1866. Zukertort lost the match by + 1 -7 :4.

Meanwhile, Zukertort had decided to make England his permanent home and became a naturalised Englishman in l878.

Zukertort tied with Anderssen for 2nd prize in a master tournament in Leipzig in 1877, but his first major international event was Paris 1878, when he tied for lst place with Winawer and won the play-oft. In 1880 he beat the French champion, Rosenthal, in a match 7-1, and the following year he beat Blackburne +7 -2 – 5. The greatest performance of his career came in 1883, when in the London Tournament he won lst prize, three points ahead of Steinitz, who came 2nd. His victory was certain two weeks before the end of the tournament when he had a score of 22 out of 23. With victory secure, he went on to lose his last three games, the strain having proved too much.

Zukertort was advised by his doctor to give up serious chess but he refused and within a short time left England for a chess tour of the United States, Canada and Europe. On his return from this tour, he left almost immediately to play a second match for the world title against Steinitz. This took place in 1886. Zukertort was in no fit state of health

for such a match, and it proved too much for him. He lost by +5 -10 =5 and returned to England a physical and nervous wreck.

Zukertort never fully recovered. He continued to play chess, but with little success. He died at Charing Cross Hospital on 20th June 1888 of cerebral haemorrhage, following a game at Simpson’s ‘Divan’.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

“One of the most talented players of all time and possibly an English Prussian Polish Jewish grandmaster, the antecedents and early career of Zukertort are shrouded in mystery, a mystery that was the more complete in that the only account of these comes from Zukertort with a lack of corroboration so great that perhaps he really was telling the truth. Whatever the truth may be it is certain that he was a great chess player, one of those who carry with them the aura of certain genius. According to Zukertort, then, he was born in Lublin of mixed Prussian and Polish descent and his mother was the Baroness Krzyzanovska. The name of his mother sounds incredibly like an invention of W. C. Fields and it is difficult to believe that his father’s name, Zukertort, was not Jewish.

Again according to Zukertort he studied chemistry at Heidelberg and physiology at Berlin, claiming to have obtained his doctorate of medicine at Breslau University. His versatility was astonishing. He spoke nine languages including Hebrew and was acquainted with several more. He had been a soldier, having fought in several campaigns for Prussia against Austria, Denmark and France; and once had been left for dead on the battlefield.

A music critic, editor of a political paper, on the staff of Bismarck’s newspaper, the Allgemeine Zeitung; gifted with a memory so colossal that he never forgot a game he played; a consummate fencer, a blindfold simultaneous player of undoubted repute (he had played as many as fifteen simultaneously blindfold) and a grandmaster with justified pretensions towards the world title: most of these attributes we have to take on Zukertort’s word. But there is enough left that is substantiated to show his great importance in the history of chess.

His early chess career had much to do with Anderssen whom he beat in a match, when Anderssen had grown old, in 1871 in Germany by +5-2, having lost a previous match to him in Berlin in 1868 by +3 -8 =1. On the strength of his win over Anderssen in the second match he was invited to play in a small but strong tournament in London in 1872 where he came 3rd below Steinitz and Blackburne. Immediately afterwards he played a match with Steinitz in which he was overwhelmingly defeated by +1-7 =4.It is unlikely that this was for the World Championship since no mention was made of the title at the time and the stakes were small, £2O for the winner and £l0 for the loser.

Despite this disastrous loss, which contained the seeds of further disasters, Zukertort felt that London was his true home and decided to stay in England, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1878. His results in tournament and match play from then on showed a steep upward curve. He was 2nd in London 1876, lst in a small tournament in Cologne 1877 and :2nd at Leipzig that year. He came lst in a big tournament at Paris 1878 where he tied with Winawer and won the play-off.

In 1880 he won a match in London against Rosenthal by +7 -l =11 and in the following year he was 2nd to Blackburne in Berlin. He was no less than 3 points behind Blackburne but he avenged this by beating him in a match in London the same year by +7 -2 =5.

A comparative setback came in a great tournament at Vienna in 1882 when he tied for fourth place with Mackenzie, below Steinitz, Winawer and Mason but in 1883 came the peak of his career when

he won lst prize in the great London tournament, 3 points ahead of Steinitz and 5.5 points ahead of Blackburne who came 3rd.

The remarkable nature of his victory is to be seen from the fact that he was sure of first prize with some two weeks still to go when he had a score of 22/23. But, ominously, his health was giving way and he had been sustaining himself by the use of drugs. He lost his last three games. It is very probable that this high point in his career was also the time when his health began to deteriorate under the excessive nervous strains by his conscious efforts to out rival Steinitz.

Thus, though he had been warned by his doctor he refused to abandon serious play and in 1886 he played his match for the World Championship against Steinitz in the USA, losing by +S -10 =5. The strain was this time too great an and he returned to England with his health completely shattered.

This was reflected in his subsequent results. =7th in London 1886 and =3rd in a smaller tournament at Nottingham that year, he had disastrous results throughout 1887: =l5th at Frankfurt-am-Main, 4th in a small tournament in London and a match loss there to Blackburne by +1-5:8.

In the last year of his life he was =7th in London in 1888 playing to the last possible moment, he died from a cerebral haemorrhage after a game at Simpson’s Divan.

Despite a career that stopped as if it were halfway, Zukertort is clearly one of the chess immortals and there is about his best game a sort of resilient and shining splendour that no other player possesses.”

Zukertort was buried in the Brompton Cemetery. He are details.

The grave was rededicated in 2012 thanks to the efforts of many chess enthusiasts.

Several opening variations have been named after Zukertort :

The Zukertort Defence in the Vienna Game, a variation advocated by Zukertort from 1871.

After 6 exd5 Bg4T 7 Nf3 Black castles, sacrificing a piece for counterattack :

The Zukertort Opening, 1.Nf3 abhorred by Ruy Lopez, used by Zukertort always as a preliminary

to 2.d4, now the fourth most popular opening move, after 1.e4, 1.d4, and 1 c4.

The Zukertort variation, in the Spanish opening, favoured by Zukertort in the 1880s :

but laid to rest soon after.

The Zukertort Variation in the Philidor Defence :

Possibly the Colle-Zukertort Opening is the most well-known

and still continues to be written about to this day.

A biography was written by Thomas Seccombe, revised by Julian Lock for The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB).

He was inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2016.

Here is an interesting article from the ruchess web site.

Dominic Lawson wrote this article in 2014.

An interesting article from chess.com

Here is his Wikipedia entry

BCN remembers Isidor Gunsberg (01-xi-1854 02-v-1930)

Nationality and Naturalisation: Gunsberg, Isidor Arthur, from Hungary. Resident in London. Certificate 17392 issued 18 May 1908.

A biography appears in The Oxford Dictionary for National Biography written by Tim Harding

BCN Remembers George Walker (13-iii-1803 23-iv-1879)

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks :

“Leading organiser and chess columnist in the last century. Born on 13th March 1803. Founded the Westminster Chess Club in 1831. Published New Treatise on Chess in 1832 and Chess and Chess Players in 1850. Edited the chess column in Bell’s Life of London from 1835 to 1870. Died on 23rd April 1879.

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

“English chess writer and propagandist. Born over his father’s bookshop in London he later became a music publisher in partnership with his father. At a time when he was receiving odds of a rook from Lewis he had the temerity to edit a chess column in the Lancet (1823-4); the first such column to appear in a periodical, it was, perhaps fortunately, short-lived. He tried his hand at composing problems, with unmemorable results; but his play improved. In the early 1830s he was receiving odds of pawn and move from McDonnell, after whose death (1835) Walker was, for a few years, London’s strongest active player.

Walker’s importance, however, lies in the many other contributions he made to the game. He founded chess clubs, notably the Westminster at Huttman’s in 1831 and the St George’s at Hanover

Square in 1843. From 1835 to 1873 he edited a column in Bell’s Life , a popular Sunday paper featuring sport and scandal. Many of his contributions were perfunctory, but on occasion he wrote at length of news, gossip, and personalities in a rollicking style suitable for such a paper. As with many of his writings he was more enthusiastic than accurate. He edited England’s first chess magazine The Philidorian (1837-8). Above all, Walker published many books at a low price: they sold widely and did much to popularize the game. The third edition of his New Treatise (1841) was as useful a manual as could he bought at the time and its section on the Evans gambit was praised by Jaenisch, Walker established the custom of recording games, and his Chess Studies (1844), containing 1,020 games played from 1780 to 1844, has become a classic. For the first time players could study the game as it was played and not as authors, each with his own bias, supposed it should be played. Throughout his life Walker helped chess-players in need. He raised funds for La Bqurdonnais, Capt. W. D. Evans, and other players, and often for their destitute widows.

After his father died (1847) Walker sold their business and became a stockbroker, reducing his chess activities but continuing ‘his many kindnesses. With an outgoing personality he enjoyed the company of those, such as La Bourdonnais, whom he called “jolly good fellows’, an epithet which might well be applied to himself. He was occasionally at odds with Lewis, who was jealous of his own reputation, and Staunton, imperious and touchy; but it seems unlikely that the easy-going Walker, who believed that chess should be enjoyed, intentionally initiated these disputes. He left a small but excellent library of more than 300 books and his own manuscript translations of the works of Cozio, Lolli, and other masters. He should not be confused with William Greenwood Walker who recorded the games of the Bourdon-nais-McDonnell matches 1834, and died soon afterwards “full of years’.

Walker is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, also known as All Souls Cemetery, Harrow Road, Kensal Green, London Borough of Brent, Greater London, W10 4RA England.

The Walker Attack is a variation of the Allagier Gambit :

Here is his Wikipedia entry

A biography written by Thomas Seccombe, revised by Julian Lock appears in The Oxford Dictionary for National Biography (ODNB)

BCN remembers Henry Edward Bird who passed away this day, April 11th in 1908.

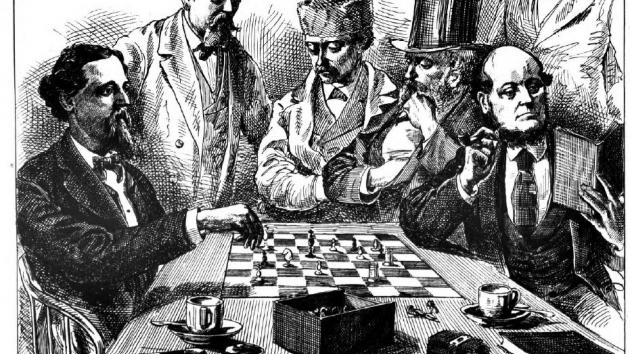

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by David Hooper & Ken Whyld :

“English player, accountant. He played in 13 strong tournaments, with erratic results; his best achievements were: Vienna 1873, a tie with L. Paulsen for fifth place; Paris 1878, fourth place shared with Mackenzie; Manchester 1890. third prize shared with Mackenzie after Tarrasch and Blackburne. He also played in numerous minor tournaments, notably tying with Gunsberg for first prize at London 1889. His most important match was against Steinitz in 1866 for the first to win eleven games. He was adjudged the loser when he was

called to the USA on business, the score standing +5 = 5—7 in favour of his opponent. This was a creditable result in the circumstances, for he played each game after a day’s work (Steinitz, however, was not so strong a player as he later became.) In 1886 Bird drew a match with Burn(+ 9—9). One of the most ingenious tacticians of his time, Bird played in the attacking style prevalent in his youth. He usually chose openings that were regarded as bizarre, although many of them, e.g. the Dragon Variation, have since gained acceptance.

Bird was probably the best known and longest serving habitue of the London coffee-house known as Simpson’s Divan. ‘A rosy-cheeked, blue-eyed, fair-headed boy’, he first attended around 1846 and was a constant visitor for more than 50 years, after which he was described as ‘majestic in stature, in girth, in the baldness of his great head, less majestic in the litter of tobacco ash upon his waistcoat … with a pleasant smiling countenance’. He suffered from gout which eventually so incapacitated him that he was largely confined to his home for the last years of his life.

Besides writing booklets on railway finance he wrote several books on chess. They are not without interest although the content is sometimes inaccurate and often disorganized. Bird’s Modern Chess and Chess Masterpieces (1887) contains more than 200 games, about half of them his own. Chess History and Reminiscences (1893) contains an account of contemporary players and chess affairs.

Bird-Mason New York 1876 French Defence, Exchange Variation :

For this game Bird was awarded the BRILLIANCY PRIZE.

The Bird Attack is variation in the Italian opening strongly advocated by Stamma and no less strongly by Biro. In May 1843 saint-Amant played it against Staunton in their first match and five years later Bird adopted the variation, playing it in many tournaments, notably with fair success at Vienna 1882, London 1883, and Nuremberg 1883.

The Bird Defence, a reply to the Spanish opening given in the first edition of Bilguer’s Handbuch, 1843. Pioneered by Bird, e.g. against Anderssen in 1854, and used on occasion by grandmasters such as Tarrasch, Spielmann, and Spassky, this defence has not gained wide acceptance.

The Bird Opening, sometimes called the Dutch Attack by analogy with the Dutch Defence. In 1873, after an absence of six years from chess, Bird played a match with Wisker. ‘Having forgotten familiar openings, I commenced adopting KBP for first move, and finding it led to highly interesting games out of the usual groove, I became partial to it. ’ Bird had also forgotten unfamiliar openings, for

1 f4 (given by Lucena) had been played by Bourdonnais, Williams, and others of that period. However Bird’s consistent adoption of the move led to its becoming a standard opening, although

never popular.

From Wikipedia :

Henry Edward Bird (Portsea in Hampshire, 14 July 1830 – 11 April 1908) was an English chess player, and also an author and accountant. He wrote a book titled Chess History and Reminiscences, and another titled An Analysis of Railways in the United Kingdom.

Although Bird was a practicing accountant, not a professional chess player, it has been said that he “lived for chess, and would play anybody anywhere, any time, under any conditions.”

At age 21, Bird was invited to the first international tournament, London 1851. He also participated in tournaments held in Vienna and New York City. In 1858 he lost a match to Paul Morphy at the age of 28, yet he played high-level chess for another 50 years. In the New York tournament of 1876, Bird received the first brilliancy prize ever awarded, for his game against James Mason.

In 1874 Bird proposed a new chess variant, which played on an 8×10 board and contained two new pieces: guard (combining the moves of the rook and knight) and equerry (combining the bishop and knight). Bird’s chess inspired José Raúl Capablanca to create another chess variant, Capablanca Chess, which differs from Bird’s chess only by the starting position.

It was Bird who popularized the chess opening now called Bird’s Opening (1.f4), as well as Bird’s Defense to the Ruy Lopez (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 Nd4). Bird’s Opening is considered sound, though not the best try for an opening advantage. Bird’s Defense is regarded as slightly inferior, but “trappy”.

According to Edward Winter Bird lived at these addresses :

A biography by Thomas Seccombe, revised by Julian Lock appears in The Oxford Dictionary for National Biography

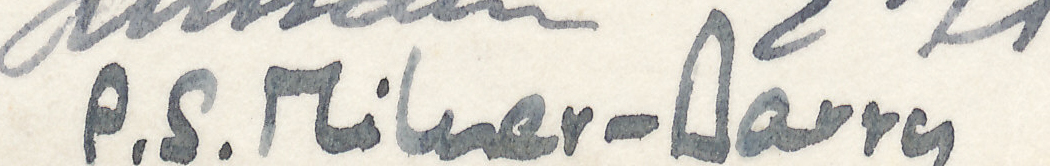

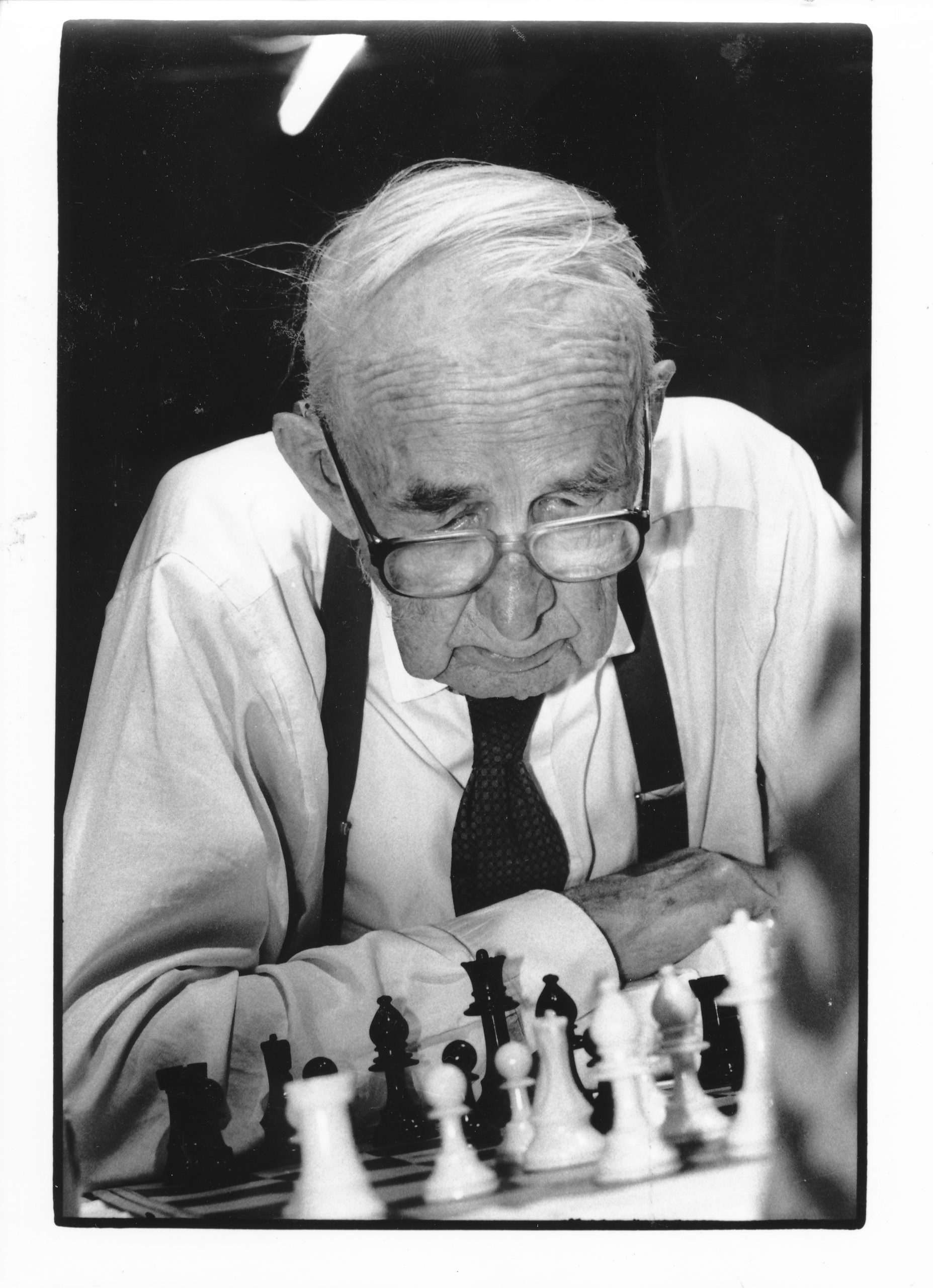

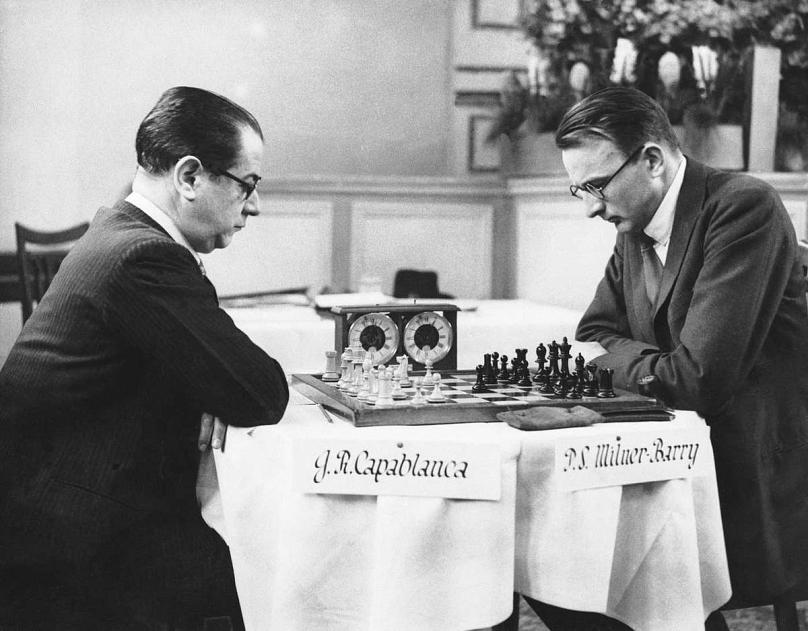

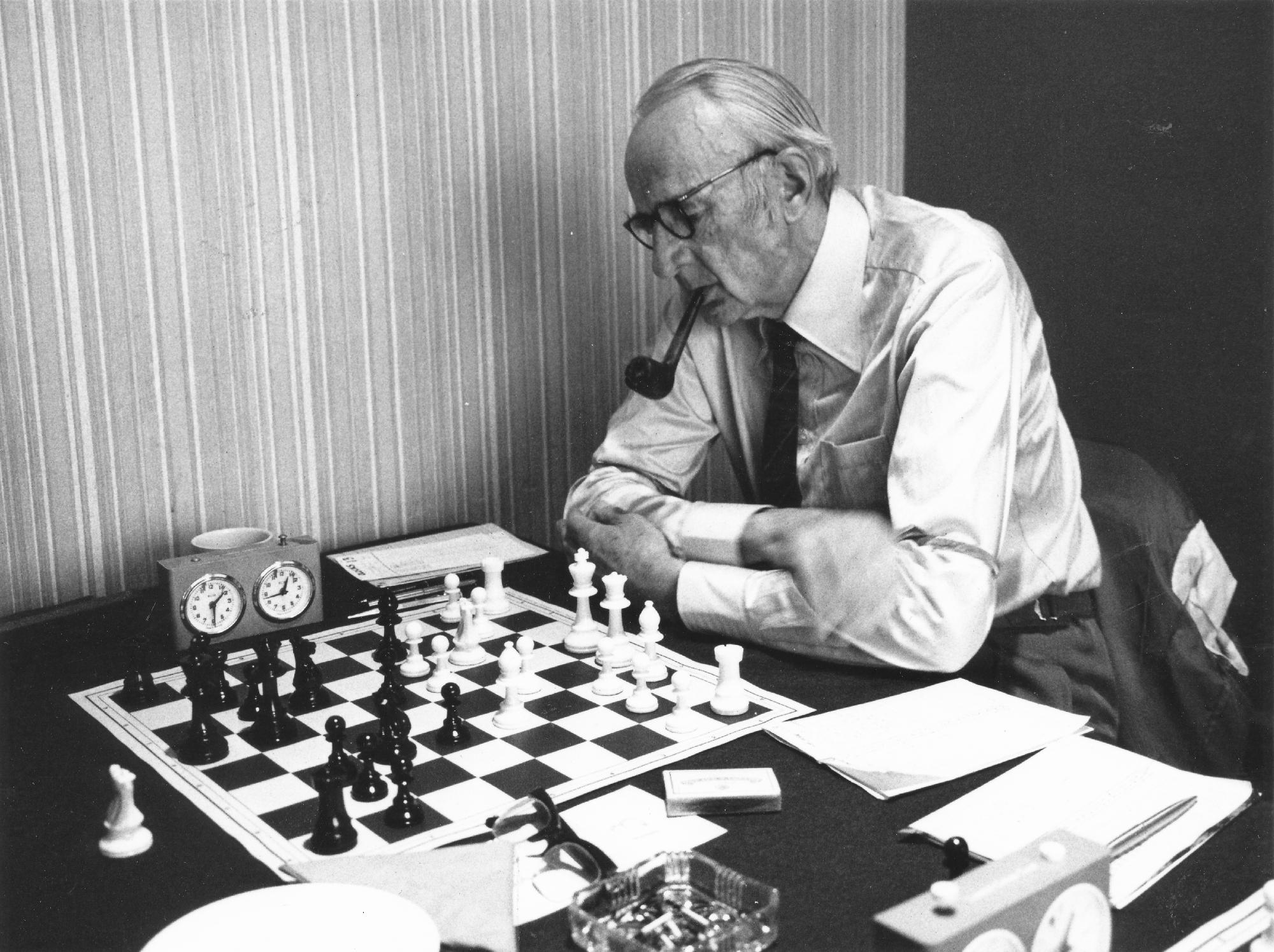

BCN remembers Sir Stuart Milner-Barry KCVO CB OBE who passed away on Saturday, March 25th, 1995 in Lewisham Hospital, London aged 88. He was laid to rest in the Great Shelford Cemetery, Cambridge Road, Great Shelford, Cambridge CB22 5JJ.

A memorial service was held for him at Westminster Abbey on 15 June 1995.

Philip Stuart Milner-Barry was born on Thursday, September 20th 1906 in Mill Hill in the London Borough of Barnet. Mill Hill falls under the Hendon Parliamentary constituency.

His parents were Lieutenant-Commander Edward Leopold (1867-1917) and Edith Mary Milner-Barry (born 17th May 1866, died 1949, née Besant). Edward was in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, H.M.S. “Wallington.” Prior to his war service his father was a professor of modern languages at the University of Bangor and Edith was the daughter of Dr. William Henry Besant, a renowned mathematical fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge University.

Stuart was the second born of six children, There was an older sister Alda Mary (18th August 1893-1938) and four brothers Edward William Besant (?-1911) , Walter Leopold (1904-1982), John O’Brien (4 December 1898 – 28 February 1954) and Patrick James . Many of the Milner-Barry family were laid to rest in the Great Shelford churchyard.

Stuart learned chess at the age of eight and his autobiographical article below goes into more depth.

He was educated at Cheltenham College, and won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he obtained firsts in classics and moral sciences.

On leaving Cambridge in 1927 he went to work at the London Stock Exchange (LSE).

According to the 1928 and 1929 electoral rolls he was living with his mother Edith and his brothers Walter and John O’Brien at 50 De Freville Avenue, Cambridge CB4 1HT:

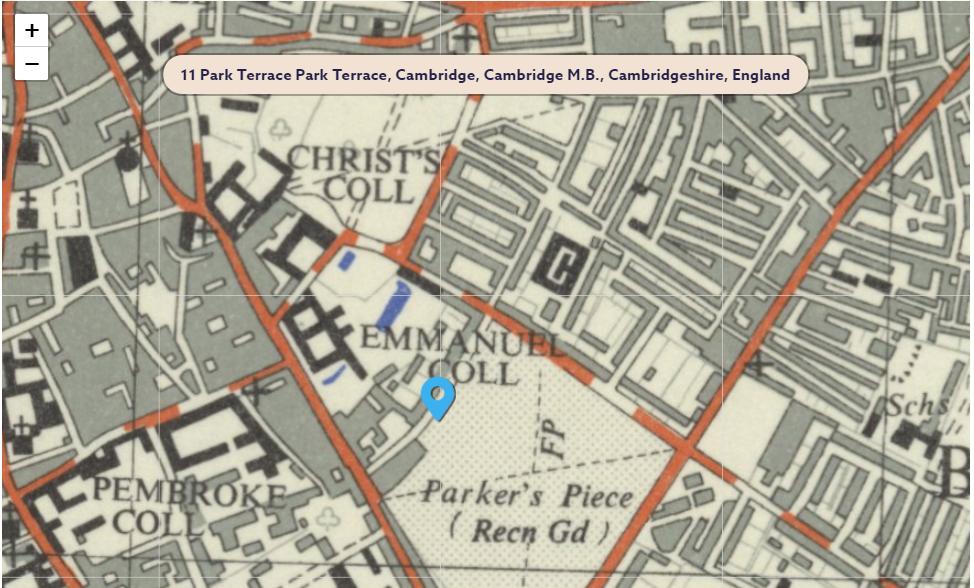

In 1931 the family had relocated to 11, Park Terrace, Cambridge which is nearby to Emmanuel College. Now living with the family was brother Patrick James.

He discovered that he did not enjoy his LSE work and switched careers to became chess correspondent of The Times in 1938.

At the time (September 29th) of the 1939 register he (aged 33) was living as a journalist in a household of three with his mother Edith who carried out “unpaid domestic duties” and sister Alda who was of “private means”.

In 1946 Stuart was awarded the OBE from the Civil Division in the New Years Honours . The citation reads that was “employed in a Department of the Foreign Office”. A modern translation of this was he was engaged in Top Secret work at Bletchley Park alongside Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman and Hugh Alexander and was thus honoured for his war work. More on this later…

After the war he worked in the Treasury, and later in 1966 administered the British honours system where he helped to facilitate the award of honours to other chess players ultimately retiring in 1977.

As well as the OBE he was made Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in 1962 and Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCV0) in 1975.

A conference room was named after him at the Civil Service Club, 13 – 15 Great Scotland Yard, London SW1A 2HJ.

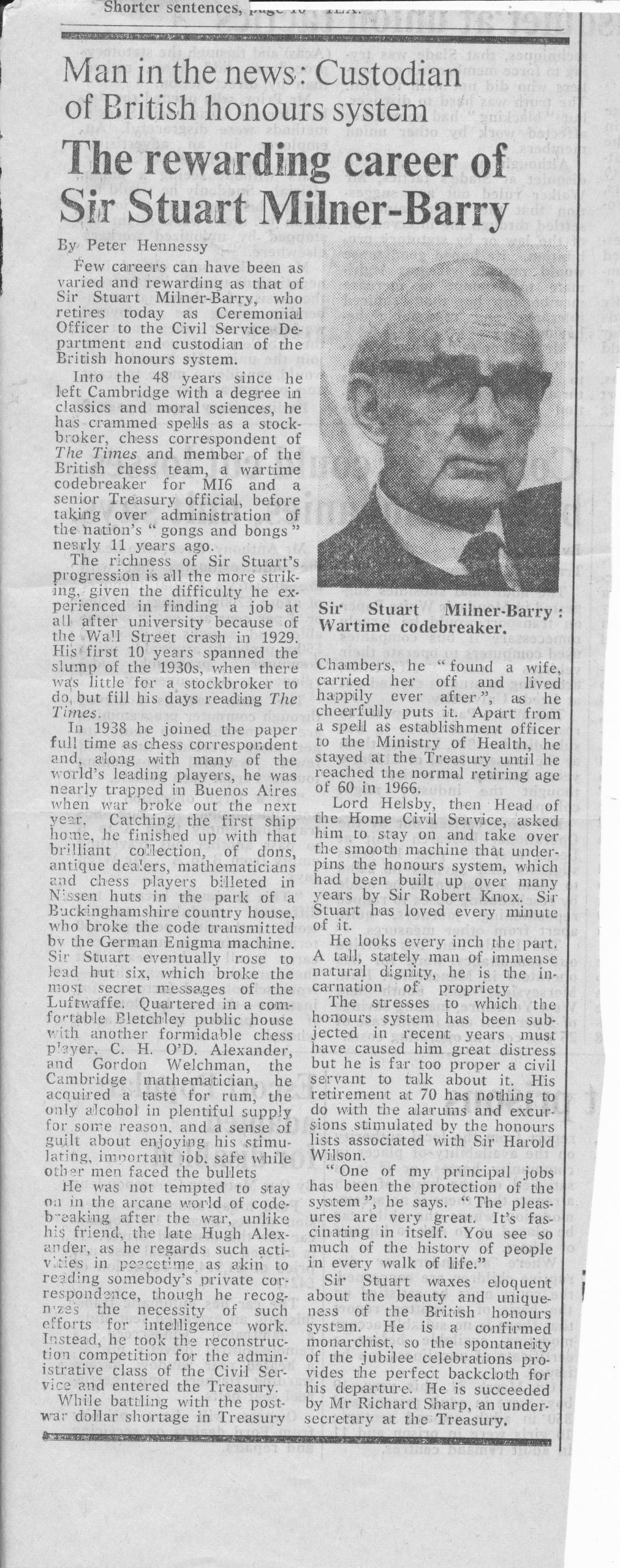

*Peter Hennessy is a renowned historian and journalist. The following was originally published in The Times in 1977 following PSMBs retirement.

“Few careers can have been as varied and rewarding as that of Sir Stuart Milner-Barry, who retires today as Ceremonial Officer to the Civil Service Department and custodian of the British honours system.

Into the 48 years since he left Cambridge with a degrees in classics and moral sciences, he has crammed spells as a stockbroker, chess correspondent of The Times and member of the British chess team, a wartime codebreaker for MI6 and a senior Treasury official before taking over administration of the nations “gongs and bongs ” nearly 11 years ago.

The richness of Sir Stuart’s progression is all the more striking given the difficulty he experienced in finding a job at all after university because of the Wall Street crash in 1929. His first 10 years spanned the slump of the 1930s, when there was little for a stockbroker to do, but fill his days reading The Times.

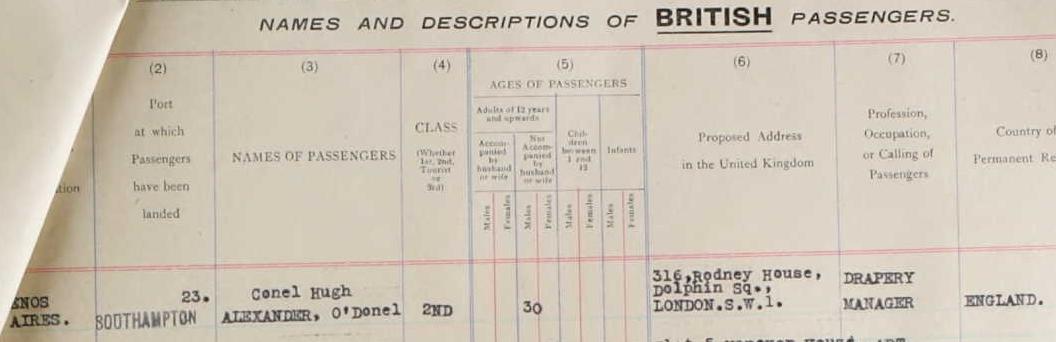

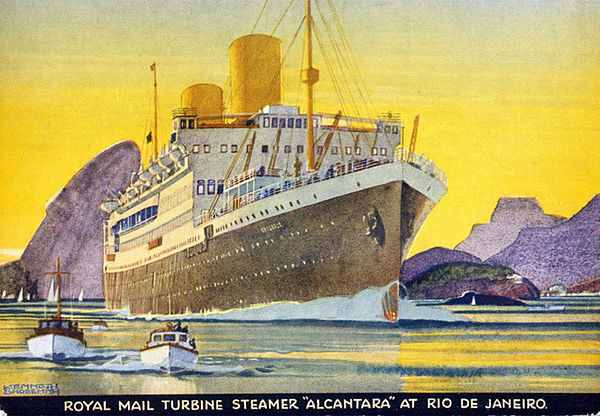

In 1938 he joined the paper full time as chess correspondent and, along with many of the world’s leading players, he was nearly trapped in Buenos Aires when war broke out the next year (ed. should be month rather than year). Catching the first ship home, he finished up with that brilliant collection of dons, antique dealers, mathematicians and chess players billeted in Nissen huts in the park of Buckinghamshire country house, who broke the code transmitted by the German Enigma machine.

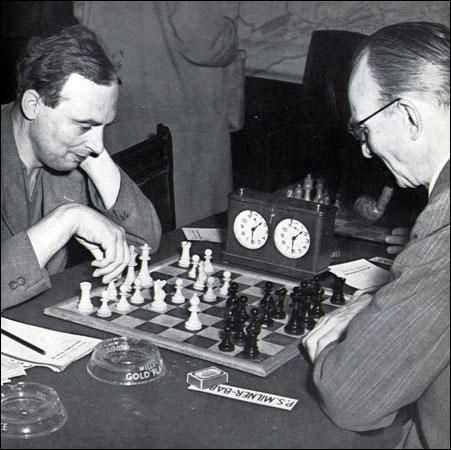

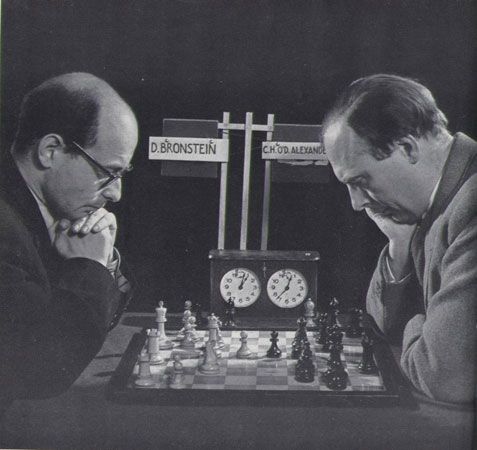

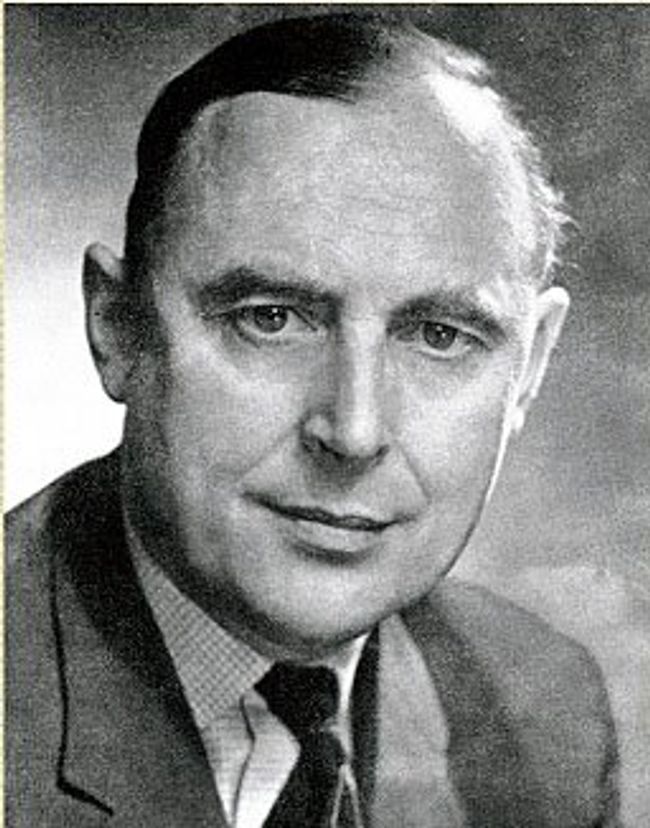

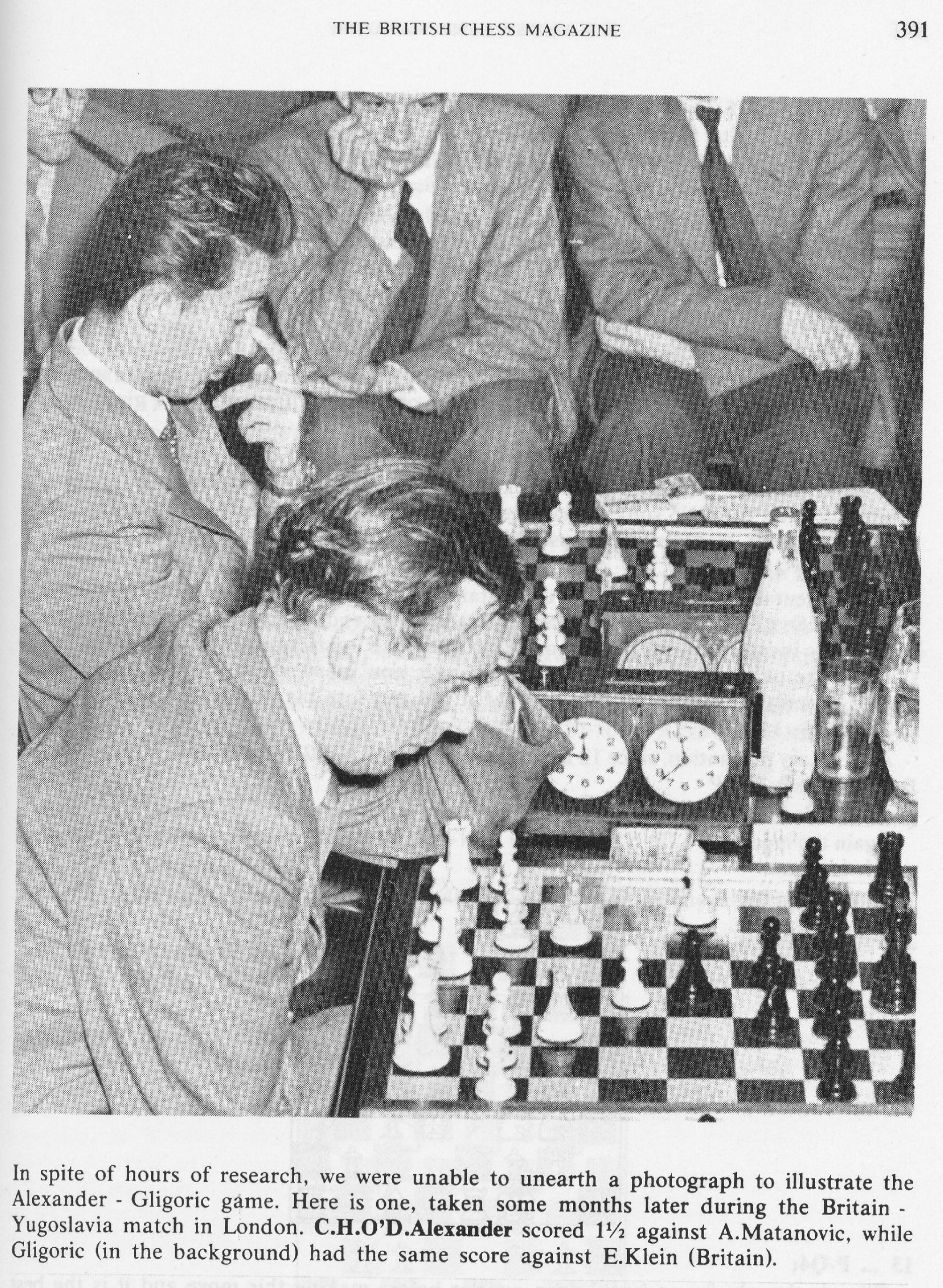

Sir Stuart eventually rose to lead hut six, which broke the most secret messages of the Luftwaffe. Quartered in a comfortable Bletchley public house with another formidable chess player, C. H. O’D. Alexander, and Gordon Welchman, the Cambridge mathematician, he acquired a taste for rum, the only alcohol in plentiful supply for some reason, and a sense of guilt about enjoying, his stimulating, important job, safe while other men faced the bullets.

He was not tempted to stay on in the arcane world of code-breaking after the war, unlike his friend, the late Hugh Alexander, as he regards such activities in peacetime as akin to reading somebody’s private correspondence, though he recognizes the necessity of such efforts for intelligence work. Instead, he took the reconstruction competition for the administrative class of the Civil Service and entered the Treasury.

While battling with the post-war dollar shortage in Treasury Chambers he “found a wife, carried her off and lived happily ever after”, as he cheerfully puts it. Apart from a spell as establishment officer to the Ministry of Health, he stayed at the Treasury until he reached the normal retiring age of 60 in 1966.

Lord Helsby, then Head of the Home Civil Service, asked him to stay on and take over the smooth machine that underpins the honours system, which had been built up over many years by Sir Robert Knox. Sir Stuart has loved every minute of it.

He looks every inch the part, a tall stately man of immense natural dignity, he is the incarnation of propriety. The stresses to which the honours system has been subjected to in recent years must have caused him great distress but he is far too proper a civil servant to talk about it. His retirement at 70 has nothing to do with the alarums and excursions stimulated by the honours lists associated with Harold Wilson.

“One of my principal jobs has been the protection of the system”, he says. “The pleasures are very great. It’s fascinating in itself. You see so much of the history of people in every walk of like”.

Sir Stuart waxes eloquent about the beauty and uniqueness of the British honours system. He is a confirmed monarchist, so the spontaneity of the jubilee celebrations provides the perfect backcloth for his departure. He is succeeded by Mr. Richard Sharp, an under-secretary at the Treasury.”

Below is the original article:

In the third quarter of 1947 Stuart married Thelma Tennant Wells in Westminster. A consequence of the “rules of the day” of the marriage was that Thelma had to resign her post in the Treasury immediately. (Ed: this somewhat antiquated view of life was finally corrected in 1972 when the Civil Service dispensed with this rule).

Lady Thelma was to support Stuart in his chess activities for their married life. She also served as the first UK Director of Women’s Chess and made many lasting friendships in the chess world. She was buried together with Stuart in 2007. Stuart himself was President of the British Chess Federation between 1970 and 1973 as well as being Director of International Chess following his presidency.

Stuart and Thelma had three children, one son and two daughters: Philip O. (born 1953), Jane E (born 1950) and Alda M (born 1958).

Stuart was knighted on January 1st 1975 for his role as the “Ceremonial Officer of Civil Service Department” between 1966-77. Technically the knighthood is known as a KCVO.

Milner-Barry was Southern Counties (SCCU) champion for the 1960-61 season.

He first competed in the British Championship in 1931 and made regular appearences as late as 1978: a span of 47 years!

In their retirement years Stuart and Thelma lived at the salubrious location of 43 Blackheath Park, Blackheath, London SE3 9RW.

In June of 1933 at the age of 27 Stuart wrote an autobiographical piece for British Chess Magazine to be found in Volume LIII (53, 1933), Number 6 (June), pp. 241-2 as follows:

I learned chess at the age of eight and played regularly after that with members of my family. My first-class practise (with due respect to my family) began at fourteen, when Mr. Bertram Goulding Brown and started a series of serious friendly games which has continued ever since, almost without interruption. The vast majority of these games were begun with 1 P-K4, P-K4, and as we both eschewed the Lopez and the Four Knights, we have acquired a fairly extensive knowledge of the older forms of the King’s side openings – King’s Gambit (all sorts), Vienna, Guioco Piano, Evans’s Gambit, Danish Gambit, Bishop’s Opening, etc. These games have undoubtedly born the most important influence in my development, apart from which the serious friendly game is to me much the most enjoyable form of chess. We each have runs of success, and there has never been much to choose between us.

(An aside : Stuart wrote a extensive obituary of Bertram Goulding Brown which appeared in British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXXV (85, 1965), Number 12(December) pp.344-45 in which he noted:

B. Goulding Brown was my oldest and closest Cambridge friend, I started playing with him in 1920, and we have played ever since, though, alas, not nearly so often since the War as in the 1920s and 1930. Our last games, when he was eighty three, were played about a year ago in the same book-congested upstairs study at Brookside as all the others had been. Both were cut-and-thrust draws: a Kieseritzky Gambit from myself and Two Knights’ (with 4.P-Q4 for White) were typical of the openings we adopted. We were planning another this Autumn, but he died suddenly and peacefully at the end of August, )

I have also been very fortunate in playing a good deal with C.H.O’D. Alexander. Our games have taken the form of a series of short matches (first player to win three games) played with clocks. Alexander was already stronger than me when he came up to Cambridge, and he won the University Championship from me in his first year and my fourth.

All three matches have been won by him, the first easily and the last two by the narrowest possible margin; a fourth now in progress looks like coming to an early and ignominious conclusion (Score 0-2-2). These results have neither surprised nor disappointed me : I would not back any player in England to do better.

(ed. For more detail on PSMBs matches with Hugh we refer to you our article on Hugh).

In 1923 I won the first Boy’s Championship at Hastings, but lost badly the following year (ed. Alexander won).

Since then I have competed twice at Hastings, once tieing with Miss Menchik in the Major Reserve for the first place and once for the last, in the Major. In between I played in the Major Open at Tenby, and came out fifth, with my first important win against Znosko-Borovsky.

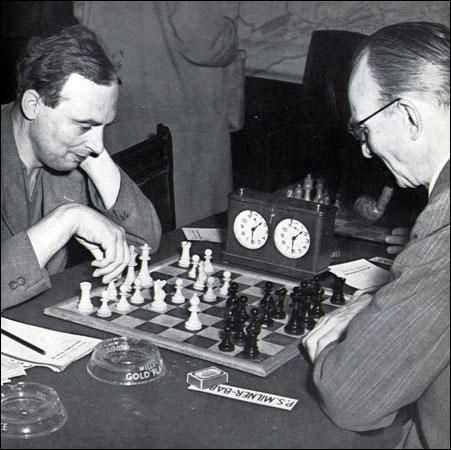

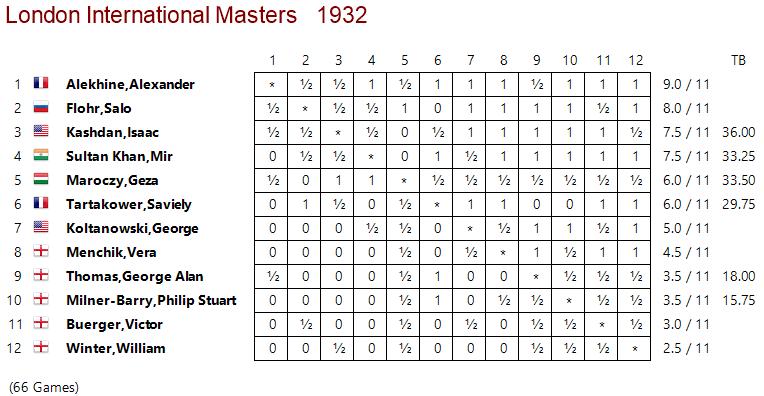

Meanwhile I played four years against Oxford, with somewhat chequered results. The first year I won against G. Abrahams, the second and third years, I played K.H. Bancroft and scored a (very fortunate) draw and a win, while finally I permitted Abrahams to fork my King and Queen with a Knight, a performance unhappily repeated by R.L. Mitchell in the following year (his Queen was pinned by a Bishop). Since then the spell has been broken. In 1931 I played in the British Championships at Worcester, and was quite satisfied with my form, though my score of 5 out of 11 was nothing to write home about. In February 1932, I have the great good fortune to fill a vacant place in the Sunday Referee* London International Tournament, an extremely exhausting but very valuable experience which I greatly appreciated.

*The Sunday Referee was a newspaper of the time which was adsorbed into The Sunday Chronicle in 1939.

My score of 3.5 out of 11, equal with Sir George Thomas and above W. Winter and V. Buerger, was quite as good as I expected. After this came the Cambridge Tournament, which, though a very delightful little congress, was a fiasco from my point of view. Three of my opponents were unkind enough to show their best form against me, and two other games I spoilt by clock trouble.

I do not expect to play much serious competitive chess in future. I admire sincerely the business man who is ready, after a hard day at the office, to undergo a further four hours of strenuous mental exertion; and who is also prepared to spend his all too brief holidays in the same exhausting pursuit. Moreover, while many players find the atmosphere of match and tournament play a stimulus or an inspiration, it only renders me nervous, and though this does not affect my play it certainly interferes with my enjoyment. As long as I can play my week-end games with B.G.B., and inveigle Alexander from Winchester to add another to his monotonous series of victories, I shall not much mind if I can only occasionally take part in congresses. ”

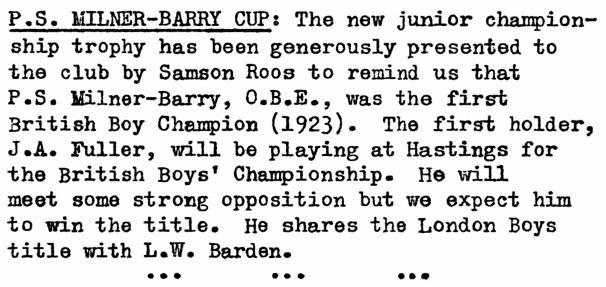

In issue #53 (April 1946) of West London Chess Club’s Gazette we have a news item concerning a newly inaugurated trophy called the PS Milner-Barry Cup:

Writing in A Century of British Chess (Hutchinson, 1934), PW Sergeant records in Chapter XXI, 1925 to 1934:

The City of London C.C.’s Championship Tournament which ended this (1933) spring deserves special mention; for it introduced an entirely new name on the list of champions, that of P.S. Milner-Barry, formerly of Cheltenham College and of Cambridge University. Ten years previously he had won the first boys’ championship at Hastings.

Now, he won the City of London Championship with a score of 11 out of 14, followed by the bearers of such noted names as R.P. Michell (10 points), Sir George Thomas (9), and E.G. Sergeant (8.5). It caused some surprise, therefore, when it was found that he was not selected as a British representative at Folkestone.

Surprisingly and disappointingly there is no direct entry in either Hooper & Whyld or Sunnucks for Sir Stuart but (as you might expect) Harry Golombek OBE does not let us down in The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977):

“British master whose chess career was limited by his amateur status but whose abilities as a player and original theorist rendered him worthy of the title of international master.

Born at Mill Hill in London, he showed early promise and in 1923 won the British Boys Championship, then held at Hastings.

He studied classics at Cambridge and developed into the strongest player there. At the university he was to meet (ed. three years later) C. H. O’D. Alexander with whom he played much chess.

Though nearly three years younger, Alexander exerted a strong influence over him and both players cherished and revelled in the brilliance of play in open positions.

By then along with Alexander and Golombek, he had become recognized as one of the three strongest young players in the country. Whilst not as successful as they were in tournaments as the British championship in which stamina was essential, he was a most formidable club and team match player, as he had already shown in 1933 when he won the championship of the City of London Club ahead of R. P. Mitchell and Sir George Thomas.

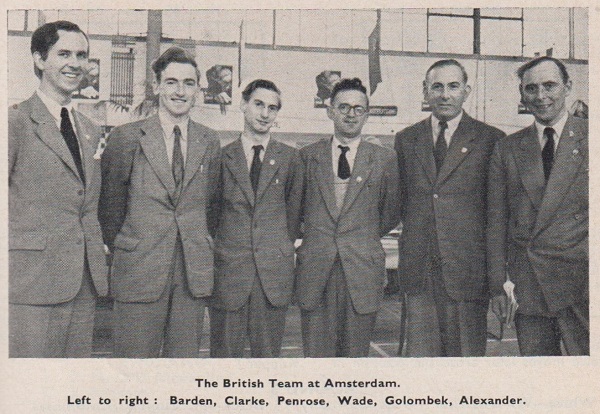

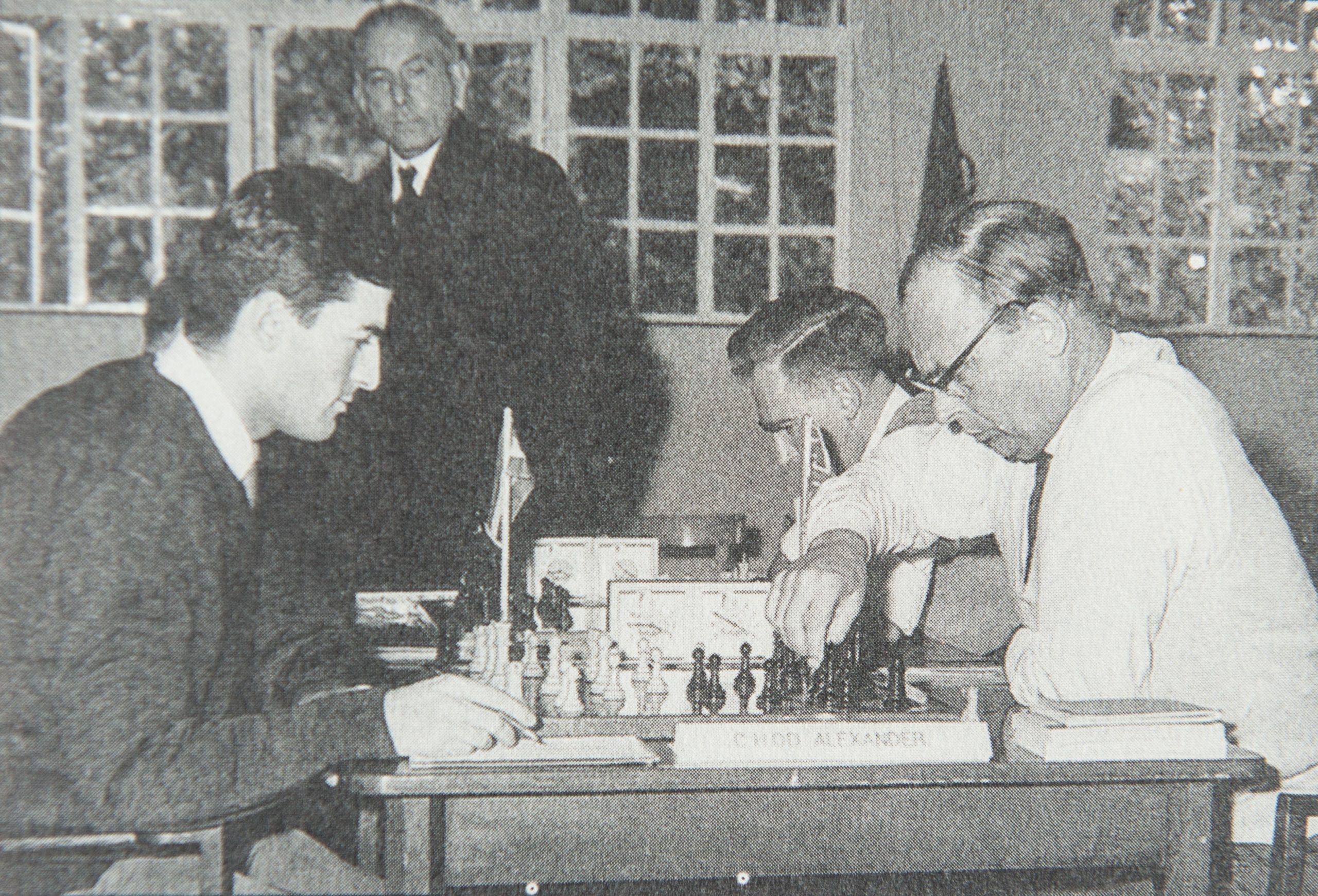

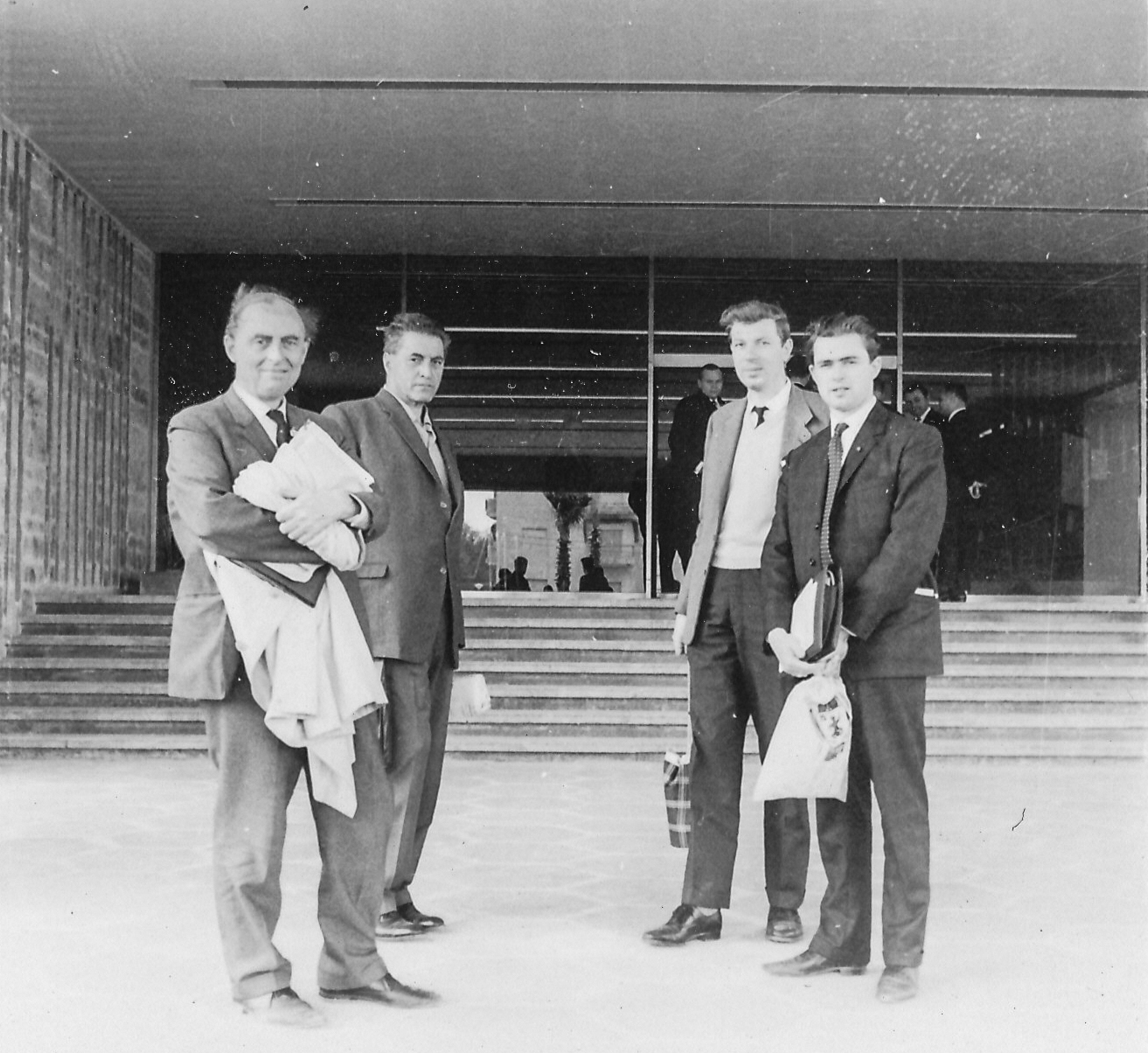

He played in his first International Team tournament at Stockholm 1937 and was to play in three more such events : in 1939 at Buenos Aires where, on third board, he made the fine score of 4/5 ; in Helsinki 1952; and in Moscow 1956 where, again on third board, he was largely responsible for the team’s fine showing.

In 1940 he shared first prize with Dr. List in the strong tournament of semi-international character in London and then, like Alexander and (later) Golombek, helped in the Foreign Office code-breaking activities at Bletchley Park for the duration of the Second World War. Staying in the Civil Service afterwards, he rose to the rank of Under-Secretary in the Treasury and was knighted for his services in 1975.

Below is footage (start at 1′ 55″) of Sir Stuart discussing the talent of Malik Mir Sultan Khan:

After the war, too, he had some fine results in the British championship, his best being second place at Hastings in 1953.

The following article is sourced from November 1995 edition* of Dragon, the Cambridge University Chess Club magazine:

(*Edited by Jonathan Parker)

“I first met Sir Stuart Milner-Barry when I was fifteen years old (1962) playing in a tournament in Bognor Regis who played some rustic king’s pawn opening against me, sacrificing a pawn for nothing in particular and then astonished by writing “castles” in full on his scoresheet. I think he used “kt” for a knight too. I thought I had discovered a true relic from a bygone age and the more I got to know him I realised the more correct that judgement was.

Milner-Barry was the last of the true gentlemen amateurs and was one of the few people I have ever met who played chess for the sheer love of the game.

A few typical incidents may give a flavour of his unique personality. First and most typical was the way he would resign: with a firm handshake, a smile and a booming whisper of ‘You are far too good for me I’m afraid!’ When I first heard those words I was totally taken aback : What was this, a chessplayer acknowledging that his opponent was better than him? Impossible!

Once, at close of play in a county match against Milner-Barry I had the extra pawn in a difficult queen and pawn ending. We analysed a little with most variations suggesting I was winning. It was the kind of position you would send for adjudication even if you are convinced it is lost. It avoids having to resign anyway and the adjudicator may always discount the pawns. But, Sir Stuart never thought like that. After ten minutes analysing he extended his hand and congratulated me.

Finally there was the splendid incident in Moscow during the (Ed. 6th) European Team Championships in the late 1970s (Ed. 1977) Stuart was then the President of the BCF and took up an invitation of his old friend the British Ambassador to the USSR (Ed. Sir Howard Smith) to visit the event. Since he was staying at the Embassy he had a KGB tail assigned to him to follow him everywhere. On one of his morning walks Sir Stuart got lost and was not certain which bridge he should be on to get back to the Embassy. So, he turned around and walked back to the not very secret policeman, followed him and asked for directions! For the rest of his stay they walked practically hand-in-hand.

Whilst most of us knew Stuart as an amiable old gent who played for Kent and in the Lloyds Bank Masters who could still play brilliant attacking games in his eighties most knew little of his distinguished career in real life.

We suspected with some justification that in his civil service career he was responsible for doling out all those OBEs to chess players in the 70s and 80s when he was in charge of the honours list.

It was the wartime work at Bletchley Park that was Milner-Barry’s greatest achievement. As everybody knows the allies won the Second World War mainly because of the brilliant code-breaking work of the Cambridge quartet of Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry. Turing and Welchman were mathematical geniuses, Milner-Barry was the supreme administrator and Alexander straddled the gap with great talents in both areas. The group of four were known as “The Wicked Uncles”

The astonishing achievement at Bletchley was not so much in breaking enemy codes as maintaining complete secrecy of the entire operation for the duration of the war. Only with such people as Milner-Barry and Alexander in charge could such a large operation be run so successfully without anybody knowing about it.

Milner-Barry’s importance in the running at Bletchley may be judged from the fact that he personally delivered the note to Winston Churchill stressing overriding importance of their work asking for more funds.

Compared with that the invention of the Milner-Barry Gambit and the Milner-Barry variation of the Nimzo-Indian are minor achievements.

Sir Stuart was proof that nice guys can be chess players although one cannot help suspecting he would achieved even better results if he had even a slight streak of nastiness about him. He would surely have not let Capablanca off the hook in Margate in 1938 when the attacking player secured a winning position against the ex-champions dragon variation and he would have surely also not let the British Championship slip from his grasp in 1953 when he finished as runner-up after losing his last two games.

He always performed well when playing in Olympiads (or Team Tournaments as they were known then) for England during the 1930s and 50s. He was, after all, one of the most naturally gifted players this county has produced. What other Englishman has two opening (or even just one) named after him?

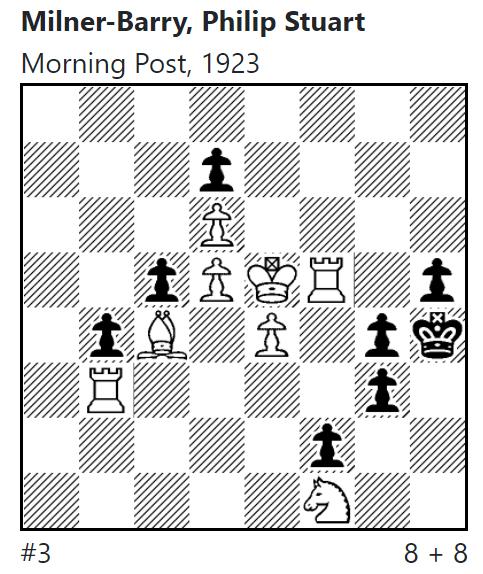

While at Cambridge while he won the University Championship in 1928, losing to Alexander in the following year, Milner-Barry composed some fine problems, a frivolity he never returned to later in his life.

An excellent though infrequent writer on the game, he wrote a fine memoir of C.H.O’D. Alexander in Golombek’s and Hartston’s The Best Games of C.H.O’D. Alexander, Oxford, 1976.”

From British Chess Magazine, Volume CXV (115, 1995), Number 5 (May), pp. 258-59 we have this obituary by Bernard Cafferty:

“Sir Philip Stuart Milner-Barry KCVO CB OBE (20 ix 1906 – 25 iii 1995) was the oldest of the British chess masters who came to prominence in the 1930s, He was always thought of in conjunction with his great friends Hugh Alexander and Harry Golombek who both predeceased him. The length of Stuart’s career is amazing – he was inaugural British Boy Champion in 1923 and was still playing for Kent first team in the Counties Championship of recent years, thus spanning a period of seven decades! Botvinnik spoke of him to me on my 1994 visit to Moscow.

Yet Stuart, who never gained the IM title, was always the true amateur and genuine English gentleman, whose sense of duty and tradition was very great. It speaks volumes of him that he agonised over whether he should attend the Times Kasparov-Short match of 1993, in a private capacity. He would have liked to watch the play, but as a former British Chess Federation President, 1970-73, he felt it was his duty not to lend any extra recognition to the contest other than that assigned it by the BCF.

Before the war, after graduating from Cambridge in Classics, he took some fine scalps including those of Tartakower and Mieses and should have beaten Capablanca at Margate 1939.

He worked, rather unhappily, in a stockbroking firm up to 1938 and it is in that capacity that his name appears on the official document that set-up the British Chess Magazine as a limited company in 1937.

During the war he played his part in the Bletchley Park code-breaking undertaking along with Alexander and Golombek, and after the war went into the Civil Service where he had a distinguished career at the Treasury. Then his career was extended as he spent his final working years in the patronage department that sifted recommendations for the honours list.

I recall asking him in 1981 if there was any chance that Brian Reilly could qualify for an award. Stuart’s diplomatic answer was to the effect that he was now retired but would drop a word in the right quarter.

Stuart represented England at the Olympiads or 1936, 1939, 1952 and 1956. At the last of these he played particularly well on fourth board. He was conscious that his old friend Hugh Alexander could not take part in Moscow because of the sensitive nature of his work in the Intelligence Service.

In playing style Milner-Barry, a tall gaunt figure, delighted in an open tactical fight.

He was The Times correspondent 1938-45, resigning the post to let Harry Golombek take over. His best result after the war, apart from the 1956 Moscow Olympiad, was probably his second place in the British Championships of 1953 at Hastings. The abiding impression of his opponents over the years must have been that here was a player who greatly enjoyed the game, win, lose or draw.

Certainly, that was my idea of him in the tussles we had from the British Championship of 1957 up to county matches in the 1980s.

We shall not see his like again. The England that formed his character is no longer with us.”

From ChessMoves, April 1995, page 3

Philip Stuart Milner-Barry was a wonderful man as well as a very strong chess-master, second board for England in his heyday, who merited in the opinion of many good judges the epithet of the English Frank Marshall, and certainly had the attitude implicit in the latter’s games ‘P-KR4 ad be damned!’ Curiously for a gambit connoisseur, he never played ‘skittles’, though we made sure our encounters in nearly all the Greenwich-Woolwich matches throughout the 1950s had a nineteenth century flavour! He simply escaped from the Stock Exchange or the Treasury, whenever required to do his duty for England, and despatched an odd Dutchman or Czech or Australian, often with his favourite Petroff or Milner-Barry (surnomme ‘Zurich’ abroad) Variation of the Nimzo-Indian, with which the latter he summarily ended my progress in the British Championship at Buxton, 1950, when our mutual respect and affectionate friendship began.

In the 1970s, being involved in leading Kent to victory twice in succession after an interval of 40 years in the Counties Championship, we travelled over what seemed like all of all England south of Birmingham. exchanging anecdotes, information and admiring comments about our much loved friends such as ARB Thomas, Willy Winter and Major Edwin Greig. It is indicative of Milner-Barry the man, who all his life, shy as he was, spoke out against injustice and helped the victims of it, that in 44 years of assiduous friendship, the only adverse comment I ever heard him make about anyone, in this case about a very arrogant and unsporting player, was ‘He is not one of my favourite young men’. As to shyness I invited him to present the prizes c. 1969 at Charlton School, where Bob Wade taught chess as part of the Mathematics to all the Lower School, when Stuart was, of course, Ceremonial Officer to the Treasury, concerned with the Honours List.

Sir Stuart as a student was taught by his lecturer friend Gordon Welchman, later 1940 his Head of Hut. They were firm friends, a band of brothers, as per the rest of the chess players and mathematicians from the Interwar years at Cambridge University.

His studies were obviously well aligned to be a stockbroker in the City, plus the tedious details of Blotters and Order Management registration.

Obvious exceptions to this University circle was Dr Jacob Bronowski who was given the suspected 5th columnist treatment by authorities in Hull. Obviously, he would have been excellent.

Exception also according to John Hevriel was if you were also from Sidney Sussex, like Staff Sgt. then an RSM Asa Briggs, who was more Contract Bridge with this all friends crossword addicts team. Asa Briggs felt that Sir Stuart was initially badly rewarded leaving Hut 6 in 1945 for HM Treasury.

Sir Stuart was a noted top cribster, his crosswords, German and thinking from how the Nazi operator would think from his side of the board, obviously helped with Bombe cribs. He always played down his role and abilities in a diplomatic way. He was the facilitator and mentor to many, especially back to Gordon Welchman in his troubled times from 1974 onwards. Sir Stuart was not happy about the proposed book of the Hut 6 Story.

He was the bureaucrat who cared for the welfare of his staff, especially on tedious protract tasks which was the norm. He was into ethics, Quadrivium, logic and rhetoric, philosophy and his knowledge of German poets and Great German thinkers would have been invaluable in solving the Enigma puzzle and how might his opposite number blunder and be sloppy in procedures.

Though never at home in close(d) positions, he was an outstanding strategist in the open game and it is significant that his most important contribution to opening theory was the Milner-Barry variation of the Nimzo-Indian Defence which is essentially as attempt to convert a close position into an open one (1.P-Q4, N-KB3; 2.P-QB4, P-K3; 3. N-QB3, B-N5; 4.Q-B2, N-B3).

Hooper & Whyld (1996) note:

“Sometimes called the Zurich or Swiss variation, this is a line in the Nimzo-Indian Defence introduced by Milner-Barry in the Premier Reserves tournament, Hastings 1928-9. This line became more widely known when it was played at Zurich 1934.”

Two famous opening lines are named after him – 4…Nc6 in the Nimzo-Indian (as above), and the gambit in the French Defence: 1.e4 e6;2.d4 d5;3.e5 c5;4.c3 Nc6;5.Nf3 Qb6;6.Bd3 cxd4;7.cxd4 Bd7;8.0-0 Nxd4;

Stuart played this line both in correspondence and over-the-board play. If Black takes the pawn with 10…Qxe5, White gets a fierce attack by 11,Re1 Qd6 (else 12.Nxd5) 12.Nb5.

There is also a sub-variation of the Caro-Kann which is named after Sir Stuart viz:

which is a Blackmar-Diemer style pawn sacrifice.

There is also a Milner-Barry variation in the Falkbeer Counter Gambit to the King’s Gambit thus:

which is an ancient line that he revived at Margate 1937.

and finally, there is a Milner-Barry Variation in the Petroff Defence:

giving a total of five named variations. How many English players have that many?

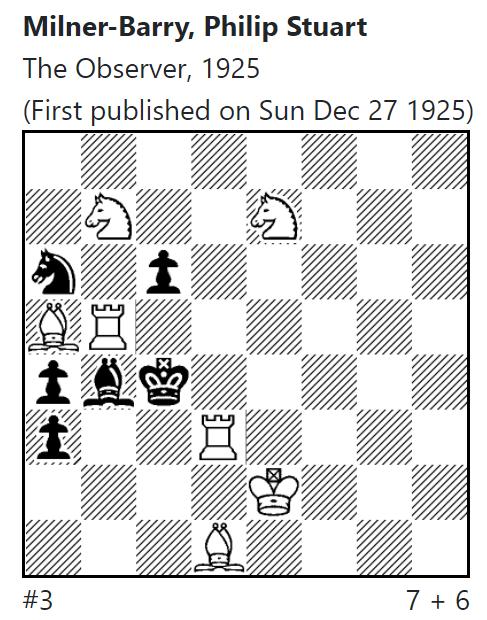

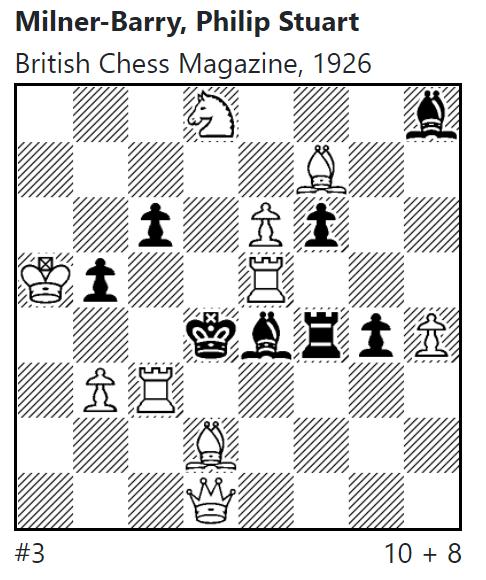

Stuart developed an interest in problem composition in the 1920s

Further examples may be found on the excellent Meson Database maintained by Brian Stephenson

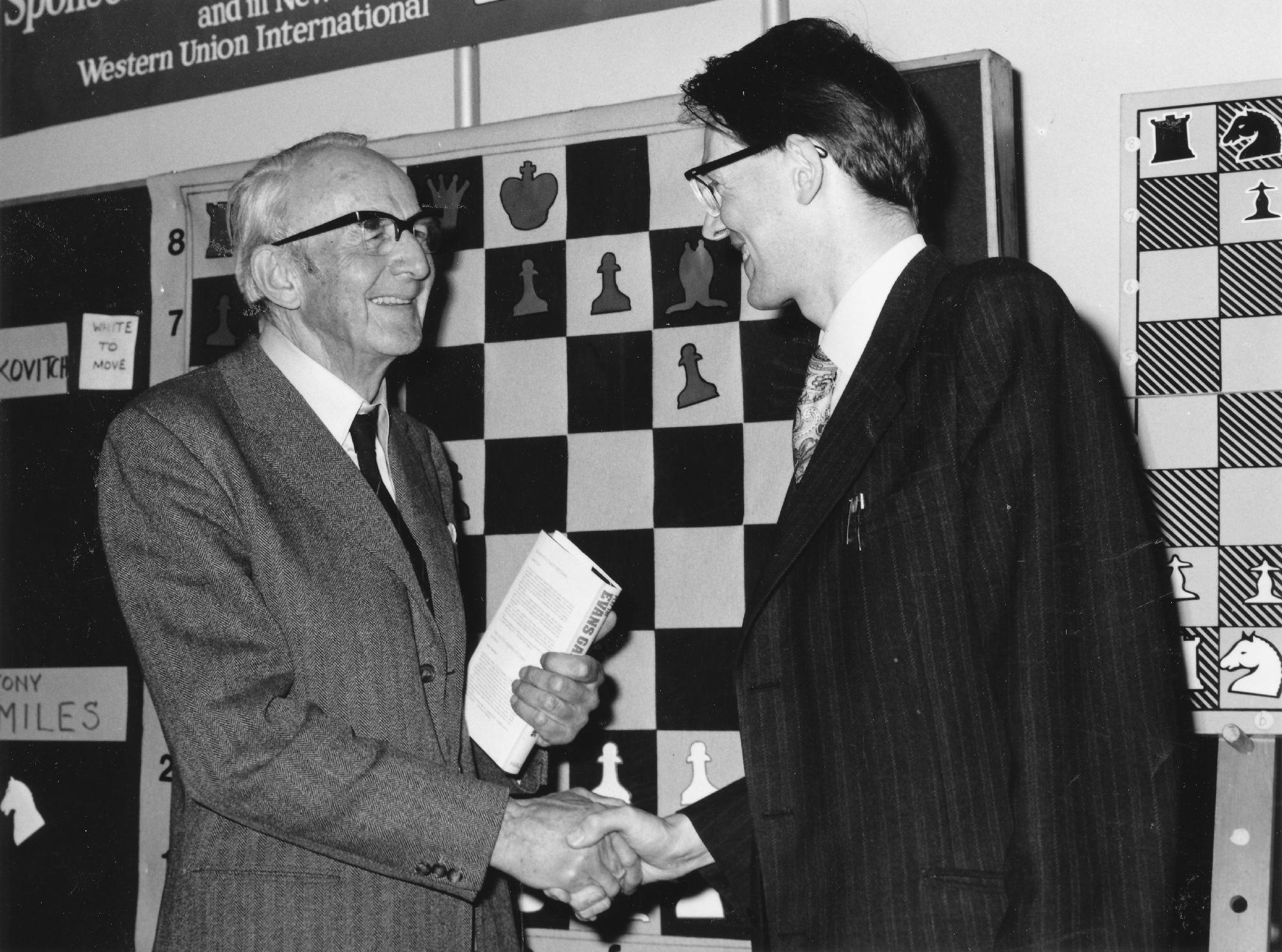

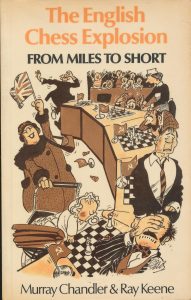

Stuart was a great supporter of the development of British chess. Nothing would have given him more pleasure than to witness the meteoric advances of English players in the 1970s. Indeed, he wrote the foreword to the English Chess Explosion (Batsford, 1980) by Murray Chandler and Ray Keene:

“It gives me great pleasure to have been asked to write a foreword for this book. Nothing has given me more satisfaction than the flowering of British chess talent that has taken place in the past few years.

Between the wars, though we had some splendid players like H. E. Atkins, Sir George Thomas and F. D. Yates, we were a second rate power at chess: in the great Nottingham tournament of 1936, for example, our quartet brought up the rear, and that was where, with occasional shining exceptions, our representatives in international tournaments tended to find themselves. Similarly, after the war in the 1950’s and 1960’s, in spite of Alexander and Penrose, we seldom achieved a really creditable place in the Olympiads.

Alexander who retired early from the arena because of the exacting demands of his profession, must have had rather a depressing time as non-playing captain.

I myself date the renaissance from the Spring of 1974 when we won a closely contested match against West Germany at Elvetham Hall.

Thereafter we went from strength to strength, with the appearance year by year of highly talented, original and adventurous young men from the Universities – Keene and Hartston, closely followed by Miles, Stean, Nunn, Mestel, Speelman, and a still younger generation of schoolboy prodigies like Nigel Short.

The peak of our performance so far has been the third place (after the USSR and Hungary) last winter in the finals of the European Team Tournament at Skara (compared with our eighth and last place at Moscow in 1977).

How did all this come about in the short space of six years? The Spassky-Fischer match of 1972 was a watershed. Since then, and the first time, it has been possible for able young men from universities to consider chess seriously as a full-time profession, or at least as a career to which they devote the major part of their time and interest, Secondly, the fruits were being reaped of the unobtrusive but devoted spadework in junior training pioneered by Barden, Wade and many others. Lastly, no doubt, sheer good fortune smiled upon us in the simultaneous emergence of a group of brilliant enthusiastic and likeable young men, five of them already grandmasters and others likely to become so before long.

It is sad that Alexander, who did so much to uphold the prestige of British chess in the doldrums, did not survive to witness the transformation. I would like to wish the BCF President, David Anderton, and Alexander’s successor as captain, all possible success for the future.”

In the March issue of CHESS for 1963, (Volume 28, Number 427, pp.147-155) William Winter wrote this:

P. S. Milner-Barry is a close friend of Alexander’s and plays like him, though not quite so well. So far the Championship has always eluded him, though he seemed to have it within his grasp at Buxton where he played superb chess for nine rounds and cracked in the last two. I fancy that the physical strain of these long Swiss tournaments

is rather too much for him. Like Alexander he has a most attractive style and one or two of his combinative games will certainly live after him.

(The original may be found here)

A brief biography, formerly displayed in the ‘Hall of Fame’ in Bletchley Park mansion. Stuart Milner-Barry had achieved fame as a champion chess player when he came to Bletchley Park early in 1940. He led the ‘cribsters’ team in Hut 6 from its opening in January 1940, becoming head of the Hut in March 1944. The work of Milner-Barry and his team lay at the heart of the triumph over the German Luftwaffe & Army Enigma codes. After the war he had an outstanding career in the civil service. Philip Stuart Milner-Barry was born on 20 September 1906 in London; He went to Cheltenham College and on to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he achieved a first in both the classical and moral sciences triposes. He became a not-notably enthusiastic stock broker, though it was chess that filled his life. He had been boy chess champion of England in 1923, playing for England before and after the war. He was chess

correspondent of the Times from 1938 and throughout the war. It was Gordon Welchman, a friend from their days at Trinity together, who persuading Milner-Barry to join Bletchley Park.