From the Batsford web site:

“International Grandmaster Andrew Soltis brings you a foolproof guide to choosing your best next chess move, every time.

There are more than 20 moves you can choose from an average position, yet Chess Masters regularly manage to select the best moves – and they do it faster, more confidently and with less calculation than other players.

This practical guide, in a fully revised and updated edition of a Batsford chess classic, explains the tricks, techniques and shortcuts Masters employ to find the best way forward, at every stage of a game. Drawing on the wisdom of some of the greatest chess players of all time, with analysis from over 180 games, it covers:

• Employing specific cues to identify good moves.

• Streamlining analysis of the consequences of moves.

• Using both objective and highly subjective criteria to find the right move – from any position.

This invaluable book provides a fascinating insight into the way Chess Masters think, and is a must for all players who want to hone their decision-making skills and cultivate a killer chess instinct.”

About the Author (updated from the publisher’s website):

“Andrew Soltis is an International Grandmaster, a chess correspondent for the New York Post and a highly popular chess writer. He is the author of many books including 500 Chess Questions Answered, The Chessmaster Checklist, How to Choose a Chess Move and How to Swindle in Chess. He lives in New York.”

At one level, the game of chess is all about decision making. At (almost) every move we have a choice to make. There may be 20, 30 or 40 possible moves. Sometimes many moves will be of equal value, but on other occasions there may be only one move to win, or draw, the game.

Decision making has two stages, involving breadth and depth of vision. What are my choices? What will happen next? While computers have no trouble considering every possible legal move in a position, humans will get very confused if they try to consider too many.

The ability to make decisions rather than just relying on instinct is what makes us human. We all have decisions to make every day of our life.

Many of them will be trivial: what topping should I have on my pizza? But others may be life-changing. Should I invite this girl out for a date? Should I accept this job offer? Should I buy this house?

Or, as Soltis opens this book:

Making a decision is one of life’s basic skills. Good decisions bring us almost everything we hold valuable. Bad decisions cost us friendships, time, money and mental ease.

Schools don’t teach us how to make good decisions. But chess can. Some of the first difficult choices we make in life are at a chessboard.

Actually, I’m not sure that schools don’t teach decision making. At least in my part of the world, when children act inappropriately their teacher will often tell them they made a poor decision.

At another level, though, chess is, far more than most skills, knowledge dependent. Which is why most books are, either directly or indirectly, concerned with adding to their readers’ chess knowledge base.

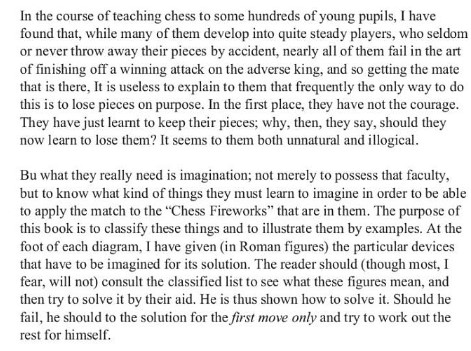

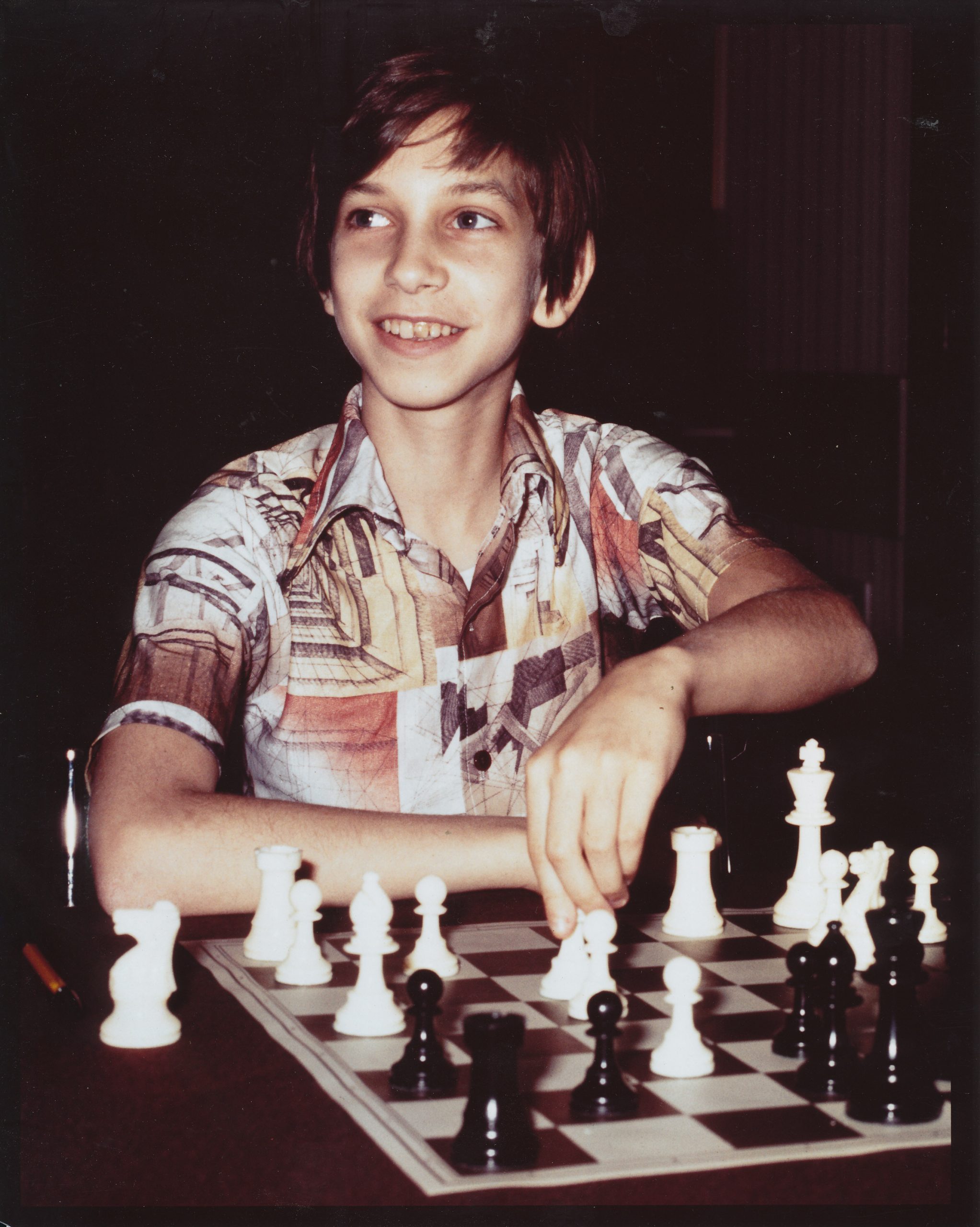

Perhaps the first book about decision making over the chessboard was Kotov’s seminal Think Like a Grandmaster. I read this back in the early 1970s and found it very helpful in getting me to think about thinking, and, in doing so, to cut down on the number of avoidable blunders in my games.

Kotov’s book has also been subjected to much criticism, and, up to a point, quite rightly so. Different players will think in different ways, and different positions require different methods of thinking.

Soltis’s book might be seen as both an expansion and a corrective. If you’re looking for a book which teaches you how to think rather than what to think about, which improves your thinking processes rather than providing you with even more chess knowledge, it might be ideal for you.

This is a completely revised and updated edition of a book first published in 2005. Many of the examples come from more recent games, so, even if you have the earlier version you might want to consider this.

Soltis has long been one of my favourite chess authors, combining readability and a story-telling style of annotation with just the right amount of analysis. Not for him the excesses and colourful metaphors of some authors (not naming names, but you know who I mean), nor the reams of computer generated variations preferred by many younger writers.

As I haven’t read the earlier edition, I was eager to look inside.

Soltis covers a lot of ground in 200 pages. We have 16 chapters, each looking at a different aspect of making decisions over the board.

Let’s whizz through them quickly.

Chapter 1. It’s Your Move. We learn that there are two types of candidate move: those that improve your position according to ‘general principles’ and those of a tactical nature: Checks, Captures and Threats.

Chapter 2. Look Smart. We have to develop excellent chessboard vision so that we can immediately identify all forcing moves, both for us and for our opponent. As Magnus said: “Always look for captures and checks, kids.”

Chapter 3: Quiet Cues. Then we have to learn how to look for positional candidates, and how to visualise where you want your pieces to end up.

Chapter 4: Drawback Detective. Another way to find candidate moves is to consider the possible drawbacks of your opponent’s last move.

Here’s a simple example (Lagno – Ju Wenjun 2018).

Here, Black is threatening Rxg3+ but 1. Be1 exf4 is crushing and 1. Rf3 invites e4 (the computer prefers the difficult to spot h5). Not liking those options, she chose 1. Kh1 instead. Ju noticed the drawback of that move, putting the king on the vulnerable long diagonal, so played 1… Bc8 followed by Bb7+, winning quickly. White did have a defence in 1. Qh5, a move which has no drawbacks.

Chapter 5: Mini-Phases. Splitting a game into opening, middlegame and ending is often over-simplistic. We can think in terms of phases such as ‘late opening’ or ‘late middlegame’ which will make it easier to make decisions and find candidate moves.

Chapter 6: Mars Moves, Venus Moves. Tactics are from Mars, strategy is from Venus, but they’re not separate: ideally a good move will have both tactical and strategic aims. However, it’s easy to think of a move purely as being positional and, as a result, miss a tactic.

Chapter 7: Intuition. Strong players will often use intuition when selecting the best move. But, as Soltis warns: Sorry, but there is no easy way to acquire it. Gaining experience and the study of master games are the proven methods.

Chapter 8: Trees. We’re in Kotov territory here as we look at the concept of analysis trees.

Chapter 9: How Much Analysis?. How far along the branch of an analysis tree should you analyse? Until you run out of forcing moves: again, something explained by Kotov.

In this position (Karpov – Antunes Tilburg 1994), Black missed a golden opportunity to defeat his legendary opponent.

Antunes played 1… Bf8 here and soon lost. After the game the players were asked if they had considered 1… b3, threatening Nb4 as well as bxc2. Karpov hadn’t seen it at all, but Antunes had rejected it because of 2. Rc8 bxa2 3. Rxd8+ Rxd8 4. Qxa5, missing that 3… Bxd8 protects a5 and the a-pawn promotes.

Chapter 10: Evaluating. When we run out of forcing moves we have to evaluate the resulting position. This requires experience along with great endgame knowledge. Soltis: Suppose you can accurately look two moves into the future. What would help you improve more? Being able to see three moves ahead? Or being able to properly evaluate what you see two moves ahead? For most players, the answer is the latter.

Chapter 11: Tree Tweaking. Sometimes you have the right idea but have to reverse the move order to get it to work, perhaps using a zwischenzug.

Chapter 12: The Four Thinking Models. These are Prioritise: focus on one candidate move and play it if it seems to work, Think Like a Kotov, using the techniques recommended in Think Like a Grandmaster, Eliminate (judge options by their drawbacks and discard accordingly) and Back and Forth, switching from one move to another, scorned by Kotov but it can sometimes work.

Chapter 13: Reality Check. Before you play a move ask yourself the question “Why did you pick that move?” Every move must have a purpose rather than just ‘looking good’. As Soltis points out, bad moves decide many more games than so-called “best” moves.

Chapter 14: The Pragmatic Imperative. Be pragmatic: choose the simplest move rather than something that might be stronger but will be harder to play. Make sure you find a good move rather than trying to find the best move.

Soltis makes a contrast between Tal, who was always happy to plunge into unclear complications, with Fischer, who took a much more pragmatic approach, preferring clear lines whenever possible.

This is from Fischer-Bisguier (US Championship 1963-64 – not 1962-63 as mistakenly given in the book). A normal move for White would be 1. a4, but Fischer preferred the pawn sacrifice 1. Nd5, which Bisguier immediately declined, remarking after the game that Fischer doesn’t make unsound sacrifices. The position had the sacrifice been accepted might not be clear to you, but it was certainly clear to Fischer. The computer considers 1. a4 and 1. Nd5 to be of equal merit.

Chapter 15: Clock Mastery. You also need to be pragmatic in allocating your time, something increasingly important with today’s faster time limits. Running into time trouble will lead to anxiety, confusion and panic.

Chapter 16: Blunder Check. The final piece of advice, again as recommended by Kotov: before you make your move the last thing you do is check that you’re not making a crude blunder.

Each chapter concludes with some helpful ‘takeaways’: quick lessons you can use in your own games. Reading these before your next tournament may well be beneficial.

You’ll see that there’s a lot of material to get your teeth into here. The examples in each chapter have been expertly chosen: they are all both entertaining and instructive, with explanations in Soltis’s typically lucid style.

If you like this author’s work, and you’re interested in the subject matter, you won’t be disappointed. Although all players will get something out of it, I’d consider the book most suitable for serious competitive players from, say, 1500 up to 2000 strength.

Like all Batsford books, it is excellently produced, but looks rather old-fashioned. If you’re my age you’ll be only too happy with this. Other readers might prefer, for example, opportunities for active learning and reader participation rather than just being lectured at. Some publishers would, no doubt, have prefaced each chapter with a page of puzzles based on the positions on the following pages. You might or might not prefer this approach.

An excellent book on an important topic, then, and, if you’re interested in the decision making aspect of chess, which you certainly should be, it can be highly recommended.

Publisher’s website here.

Sample pages on Amazon here.

Richard James, Twickenham, 21st February 2025

Book Details :

- Paperback: 208 pages

- Publisher: Batsford; 1st edition (4 July 2024)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:1849949239

- ISBN-13:978-1849949231

- Product Dimensions: 15.29 x 1.65 x 23.37 cm

Official web site of Batsford