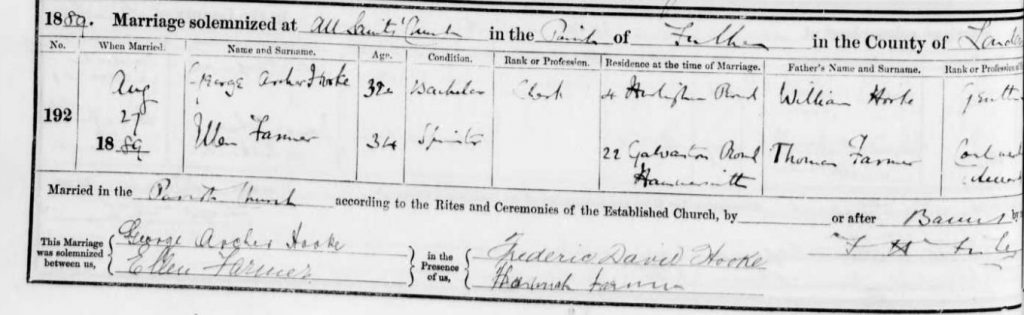

Last time we left George Archer Hooke at the age of 32 in 1889, just having married 34 year old Ellen (Nellie) Farmer.

George and Ellen didn’t waste a lot of time starting a family. Their first child, a daughter named Mildred Alice (was her middle name a tribute to George’s sister?) was born on 18 September 1890.

The 1891 census found George, Ellen and baby Mildred at 22 Galveston Road Putney (just off the South Circular between Putney and Wandsworth). George, Ellen, Mildred. By now Ellen was expecting another child, and, on 7 November that year, they welcomed Frances Louisa into the world.

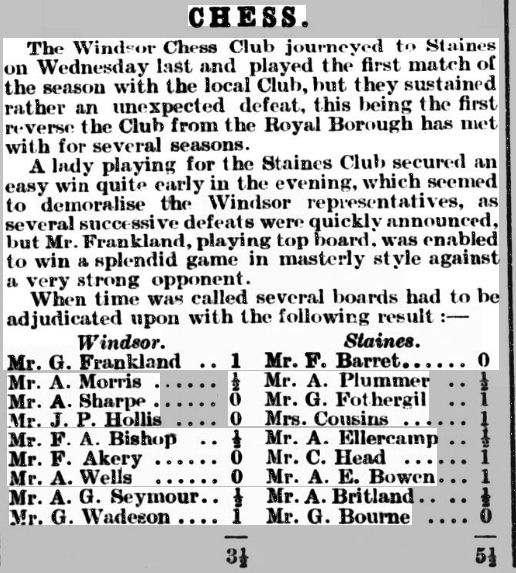

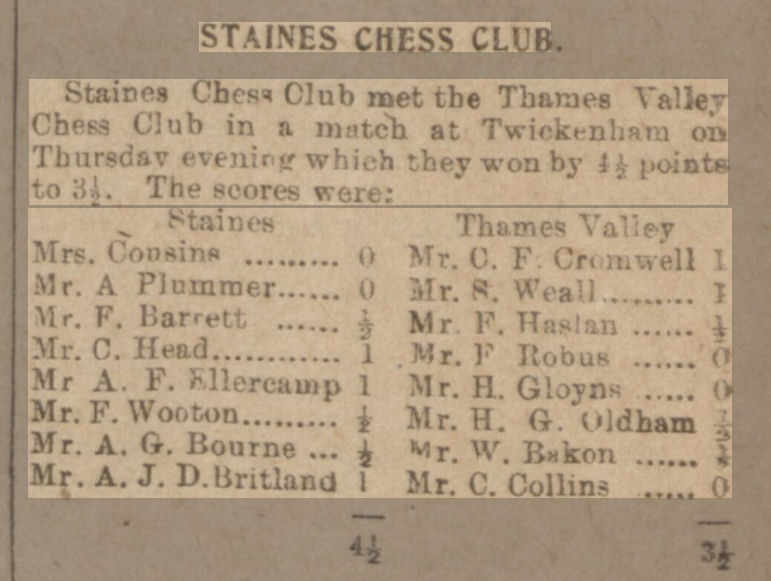

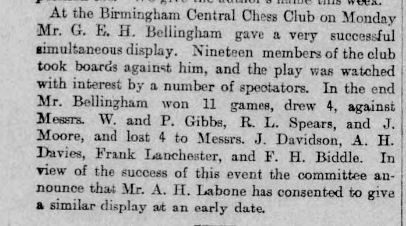

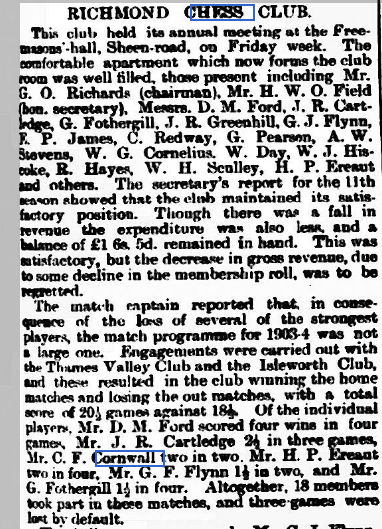

George was still playing club and county chess regularly.

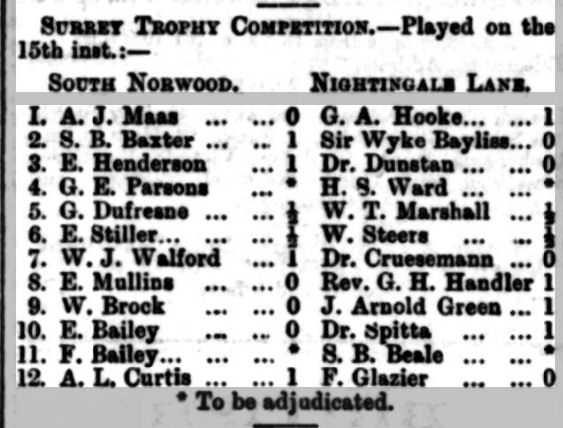

In this game he demonstrated commendable aggression in the middle game against tinned milk pioneer Arthur James Maas, who, perhaps unwisely, opted for one of his opponent’s favourite openings. Click on any move for a pop-up window.

On the very day this game was published, George had another reason to celebrate: the birth of a third daughter, named Beatrix Georgina Ellen.

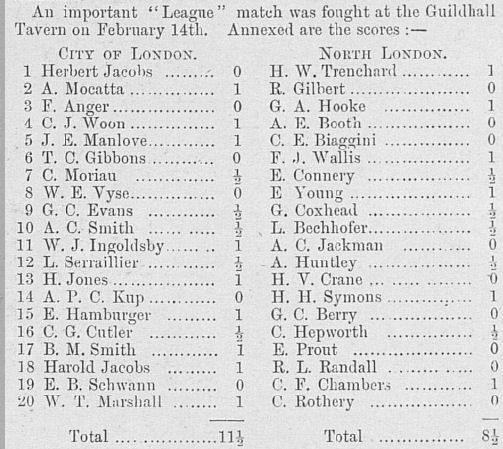

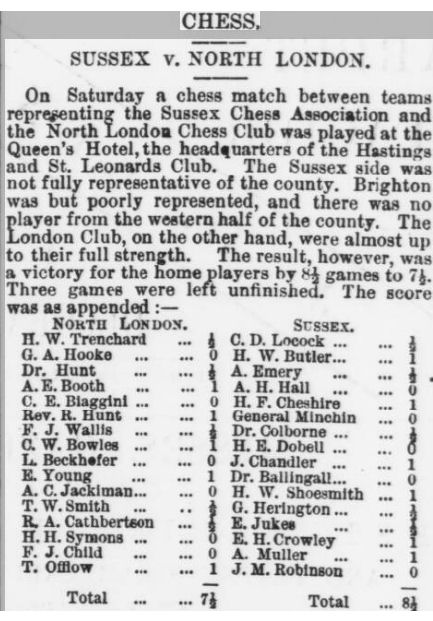

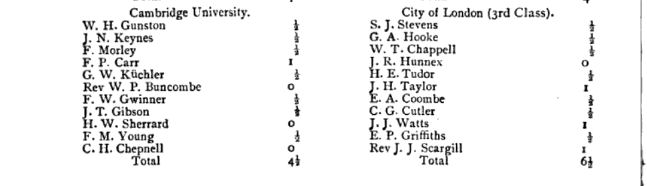

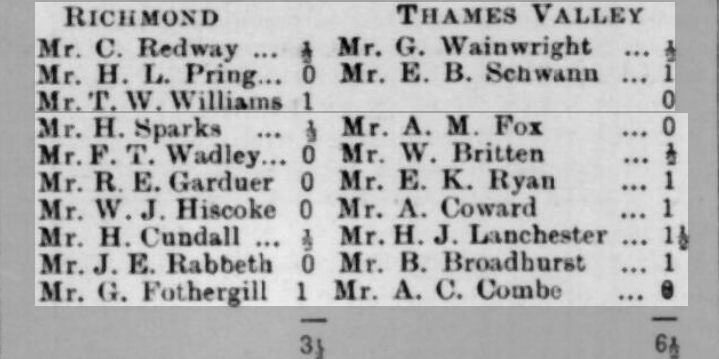

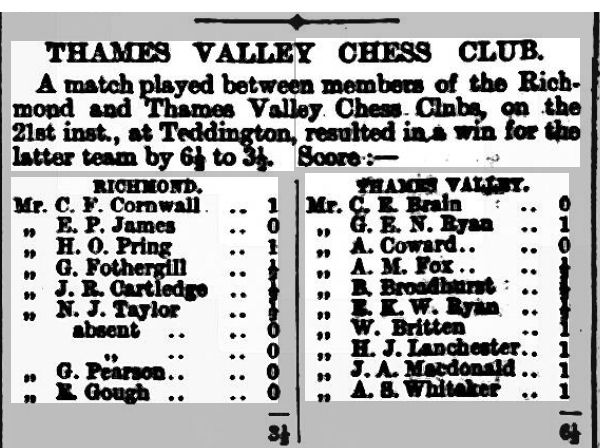

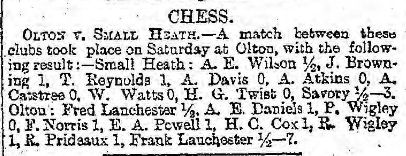

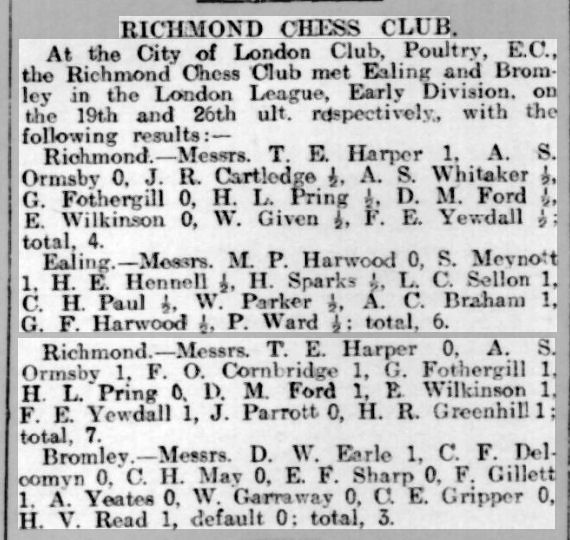

George Archer Hooke was a member of two clubs but chose to play for North London in the London League. This league had started in 1888, and North London followed Athenaeum as title winners in the 1889-90 season. Their second title would come in 1898-99. Here they are, in 1894, losing to George’s other club.

Although his team lost, George won his game against Prussian born Fancy Stationer(!) (John Charles) Frederick Anger. There are some interesting names, as always, on both sides. Regular readers will spot Edward Bagehot Schwann playing for City.

The North London Board 17 is also of interest. Back in the 1960s my father, who sang in his church choir, had a score of Handel’s Messiah, edited by the wonderfully named Ebenezer Prout. I always remembered this – and here he is in 1894 playing chess in the London League. Wikipedia confirms that Ebenezer lived in Hackney and played chess: something I never knew until now.

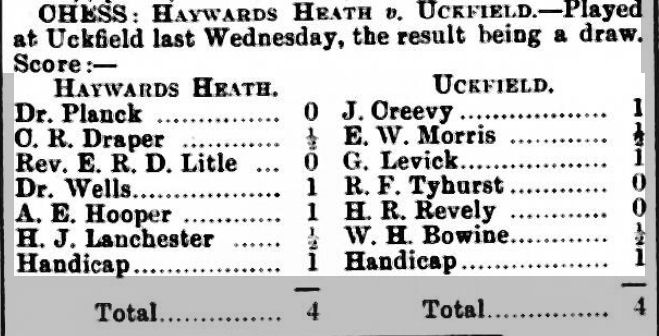

Three months later his team encountered someone even more interesting.

The Sussex board 14, assuming the middle initial should have been A rather than H, was none other than star of The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict and “Wickedest Man on Earth” Aleister Crowley.

A fourth daughter, given the names Ella Kathleen, was born on 8 April 1895, and she would be followed, on 28 November 1896, by George and Ellen’s last child and only son, Cyril George.

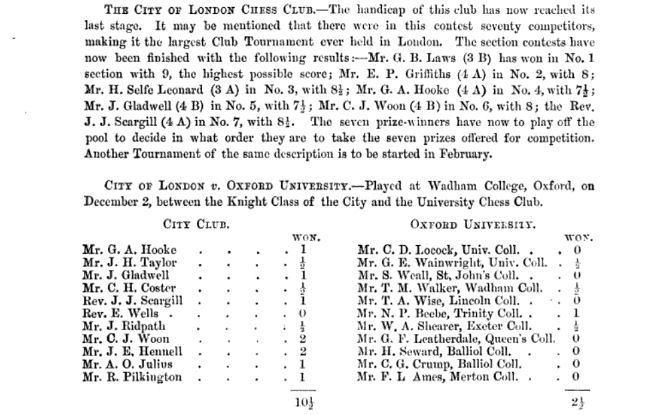

The City of London Championship, which, as regular readers will be aware, would soon become very strong, attracting London’s leading amateur players, had started in 1890, and George was often amongst the entries. The closest he came to winning the event came in the 1896-97 season, in which he won his section but lost to the winners of the other three sections in the play-off, with Thomas Francis Lawrence eventually winning his second title.

In this game of fluctuating fortunes against an Essex player, Hooke escapes from a poor position. His opponent seemed to lose the thread of the game, allowing George’s hanging pawns to become a strength rather than a weakness.

In 1897 his playing strength was recognised by the national selectors, who picked him as a reserve for the Anglo-American Cable Match. His services weren’t required, but he must have felt honoured to have been considered for such a prestigious event.

There are several games from this period of George Archer Hooke’s life available online, but unfortunately most of them are losses. This club game against Walter Montagu(e) Gattie (whose son plays a walk-on part in this Minor Piece) was a missed opportunity: George was beating his formidable opponent but allowed a sacrifice for a perpetual check.

Hooke lost this game against another strong amateur player of the time, Charles Hugh Sherrard, whose sacrificial attack was crowned by an attractively quiet 24th move.

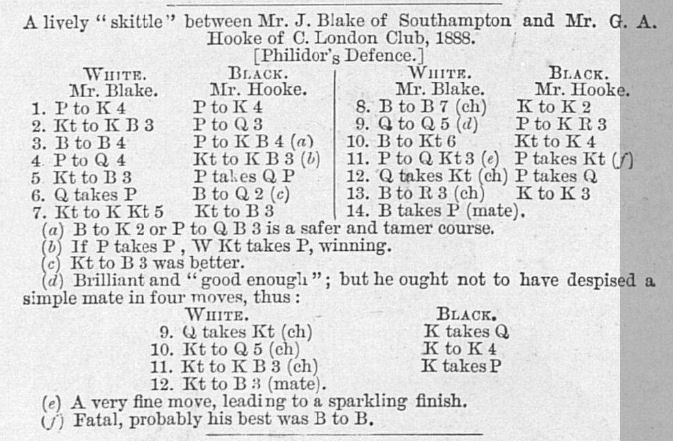

This is another loss against Joseph Henry Blake: an interesting game concluding with a magnet sacrifice to draw the king out, not dissimilar to the one Blake missed against the same opponent a decade earlier (you saw it in the previous article).

By 1900 Hooke had joined another club: Nightingale Lane, based in Clapham, which, belying its rustic sounding name, was one of the strongest clubs in Surrey, winning the Surrey Trophy in the 1902-03 season. Here he is on top board, ahead of Sir Wyke Bayliss.

By the time of the 1901 census the family had moved three miles away, to 59 Cloudesdale Road Balham. With five young children at home the family now needed to employ a domestic servant, and Ellen’s mother Hannah Farmer was also there, perhaps helping look after the children.

By now there was a lot more chess action for newspapers to report and consequently less space for amateur games from club matches and tournaments, so George’s games were no longer being published. However, the big moment of his chess career was still to come.

This was in 1903, when he finally made his one and only international appearance in the Anglo-American Cable Match. He was pitted against Hermann Helms, an important figure in US chess over many decades, helping to organise the great New York 1924 and 1927 tournaments, and, in 1951, assisting Regina Fischer in finding chess opportunities for her young son.

Although he lost this game, he put up a good fight. You might think he was rather unfortunate not to share the point. 49… Ne3+ was a very natural move but resulted in the loss of his last pawn. 49… Ne1+ would probably have held the draw.

As the decade wore on Hooke’s name appeared much less in chess columns, but he was still active, and would later remember some of his games from this period as among his favourites.

By 1911 the family had moved house again, just half a mile away, to 100 Drakefield Road Upper Tooting, right by Tooting Common. The census records all five children at home, although Mildred is now studying at Newnham College Cambridge. There’s no occupation listed for Frances, but the three younger children are all at school. The girls all attended St Paul’s Girls School in Hammersmith, while Cyril was educated at St Paul’s School nearby.

Mildred would soon be joined at Newnham by her sister Beatrix, known as Trixie in the family.

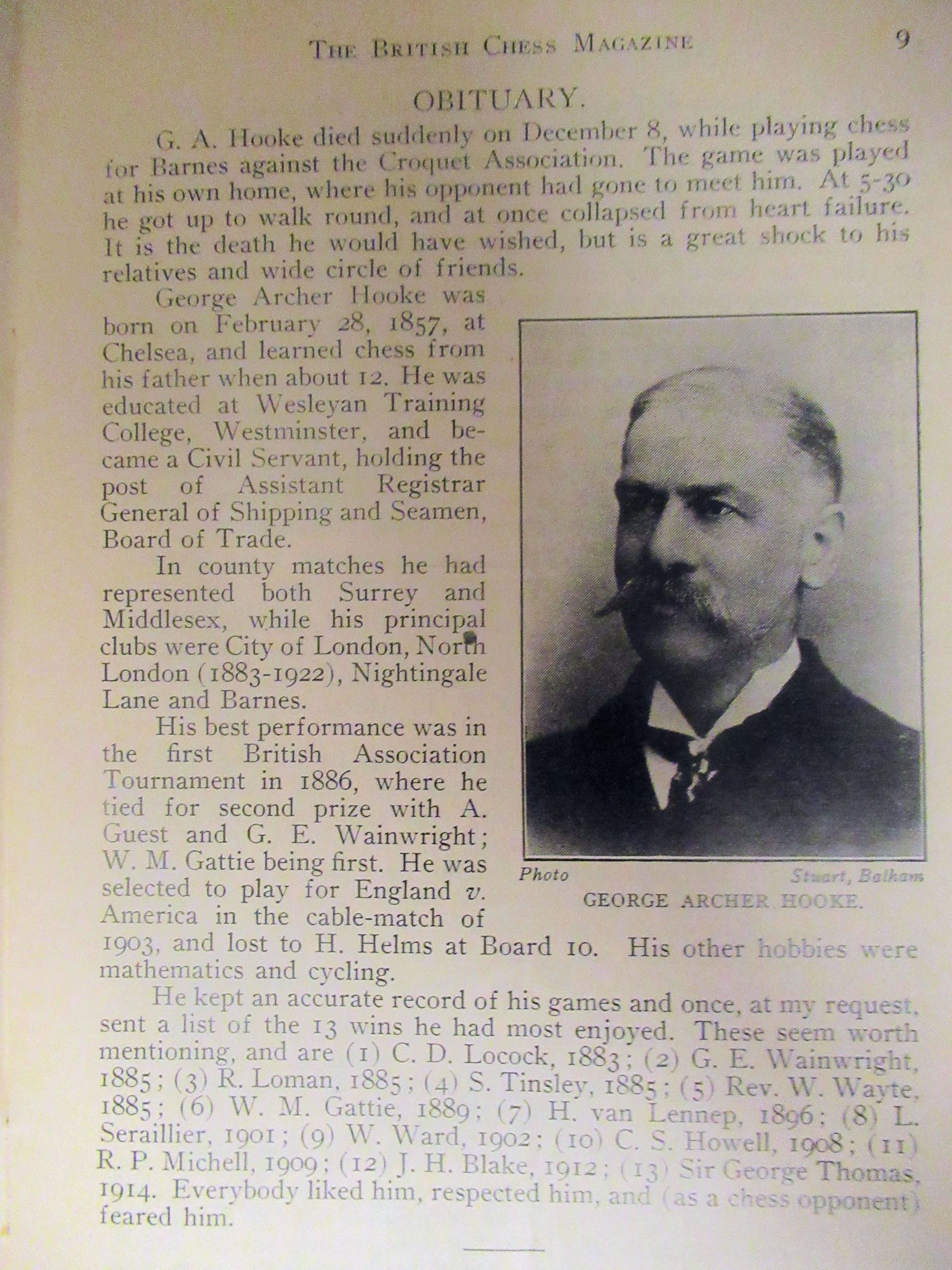

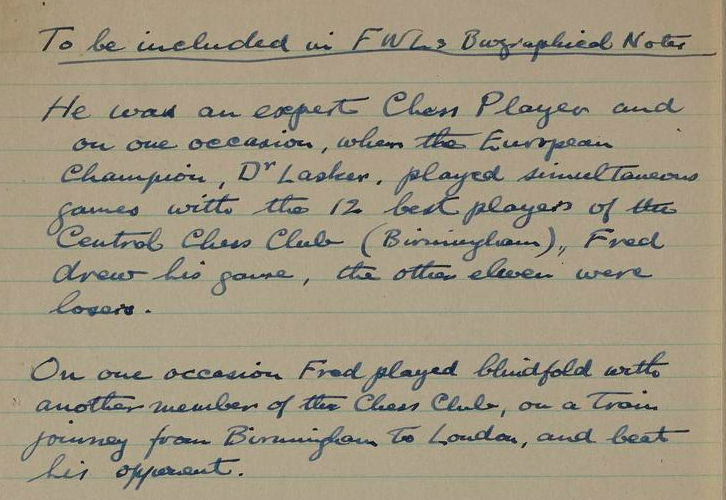

With Trixie now having joined Mildred at Cambridge, George (seen in the photo above from about this time) wrote her regular letters between 1912 and 1914, which, remarkably have survived within the family to this day.

They include several mentions of George’s favourite game.

I shall leave your sisters to tell you of their gaieties. My share has been another successful match game at chess but mainly my energies have been occupied with the Men’s Society and exceptional demands at the Office. (10 Nov 1912)

1913 seemed a quiet year for chess – at least he didn’t write much about it in his letters to Trixie, but the first few months of 1914 were busy.

I played chess on Friday and did not finish my game. Whether it will be adjudicated a win for me I do not know. My advantage was a very minute one. (18 Jan 1914)

My Chess has been successful. On Tuesday I was delighted to beat the Champion of the City Club and on Friday I drew with a weaker player. (15 Feb 1914)

This victory would have been the game against Sir George Alan Thomas mentioned in his BCM obituary below. Sadly, I haven’t been able to identify the circumstances and find the moves of this game.

During the past week I have been fortunate enough to win 2 games of Chess I have 2 more to play – to-morrow and the next day and shall then give it a rest. (1 Mar 1914)

There was less chess activity during the First World War: it’s not clear whether or not George continued playing, although there are records of his participation in county matches after the war.

By the time of the 1921 census the family had moved to 3 Woodlands Road, Barnes, described by an estate agent today as a quiet cul de sac conveniently located within a short walk of Barnes station, which offers a frequent service into Waterloo. George, Ellen and Ella (working as a statistician for the League of Nations) were at home. Mildred was working as a maths teacher King Edward VI High School for Girls, Edgbaston, Birmingham. Frances was teaching domestic science at the Misses Mullins Ladies School in Eastbourne (about which I know nothing). I haven’t been able to locate Beatrix: perhaps she was abroad. Cyril was serving in the Royal Field Artillery in Fyzabad, United Provinces, India.

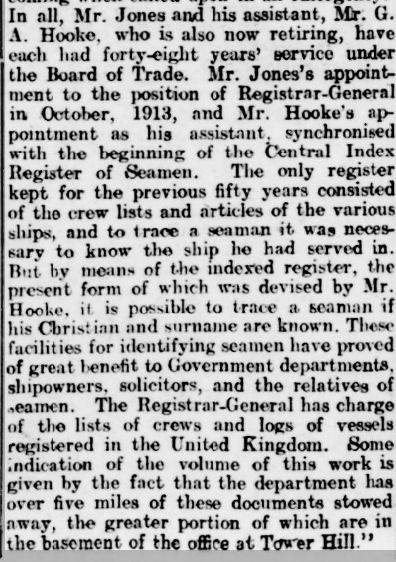

Now he was in his mid 60s, it was time for George to retire from his job with the Board of Trade after 48 years’ service.

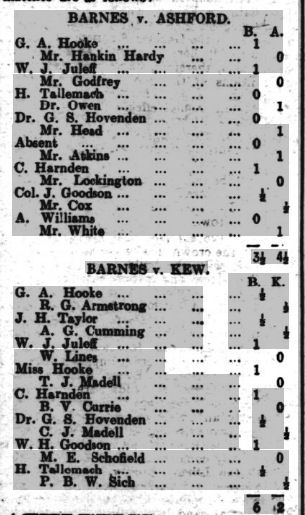

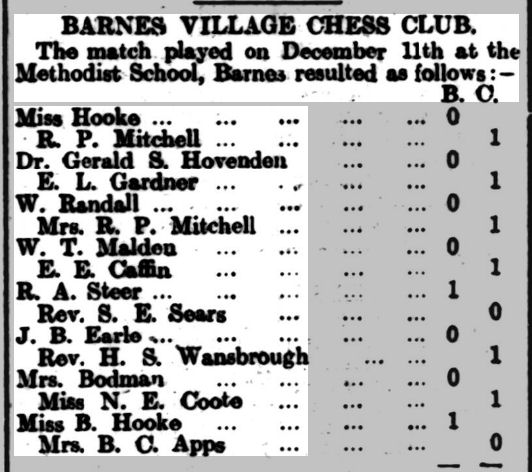

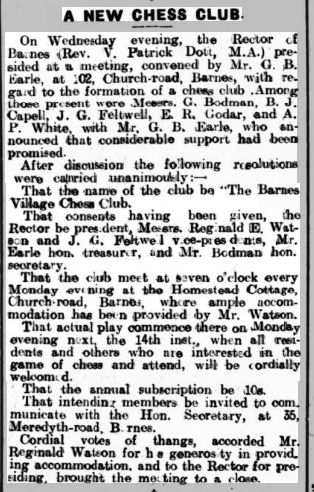

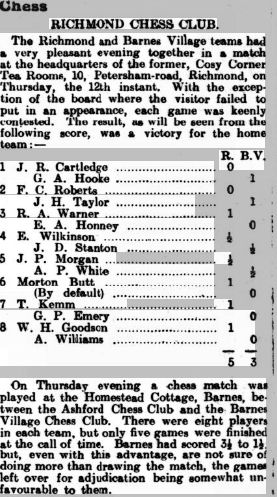

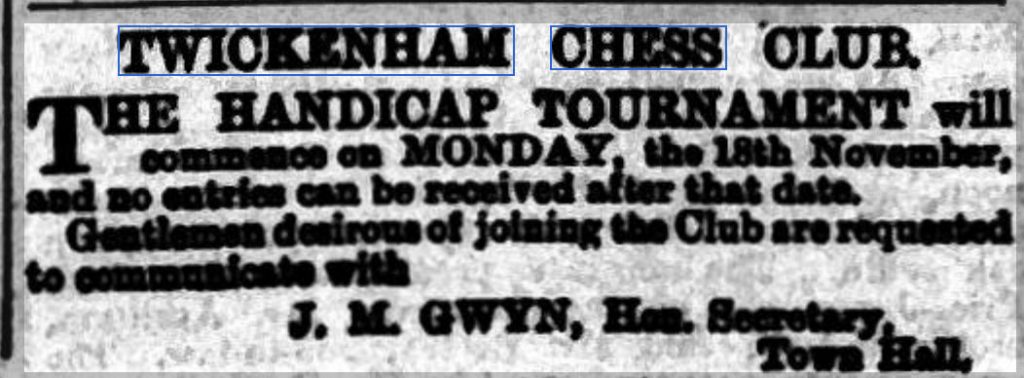

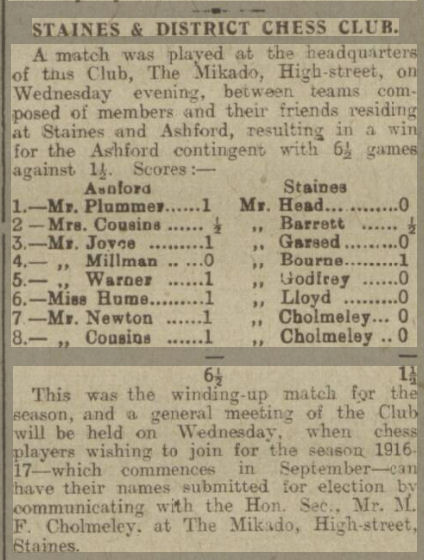

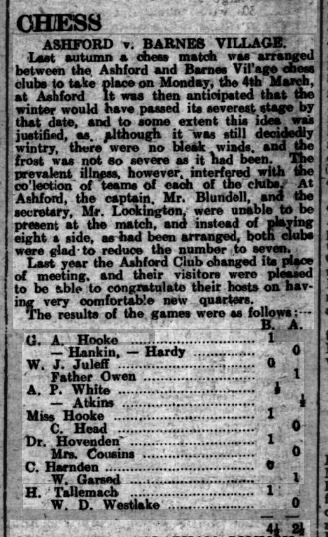

Then, as you saw last time, Barnes Village Chess Club was formed in 1924, right on his doorstep. Now retired, he would have had more time on his hands, and was happy to sign up, soon finding himself with the job of club secretary. The Richmond Herald was eager to report results from clubs within its circulation area, so we suddenly have a lot of information available about George and his new colleagues, not to mention their opponents.

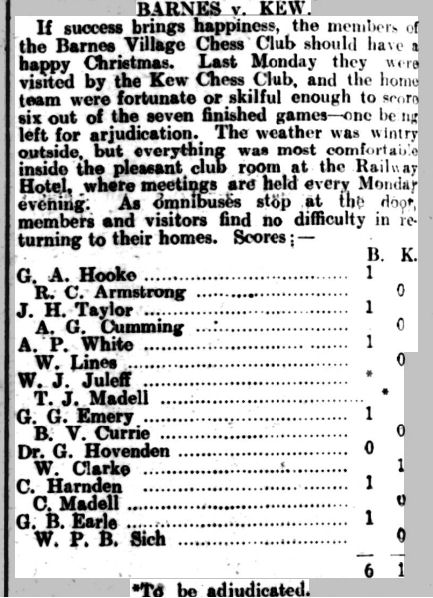

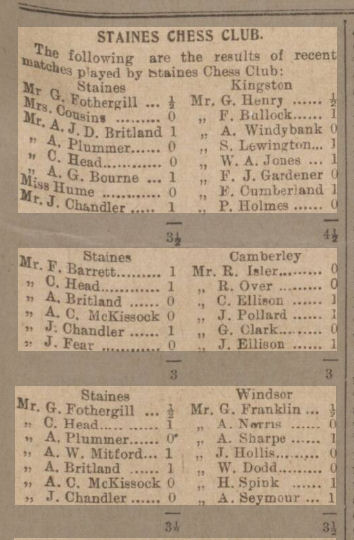

There were a number of new clubs formed in the Richmond area in the inter-war years. One such was Kew, who played Barnes Village in this 1927 match.

It’s good to know that omnibuses stopped at the door of the Railway Hotel, and here it is, with an omnibus stopping outside.

It’s now been converted into flats, but today the 33 bus will take you back to Richmond, Twickenham and Teddington.

Speaking of pubs, if you have a long memory, the surname of the Kew Board 8 might look familiar. His initials are the wrong way round, but this was Percy Bertram Wardell Sich, the son of Steinitz’s opponent Alexander Sich.

The following year was a sad one for George, with the death of his beloved wife Ellen. Perhaps his sister Alice moved in with him at this point.

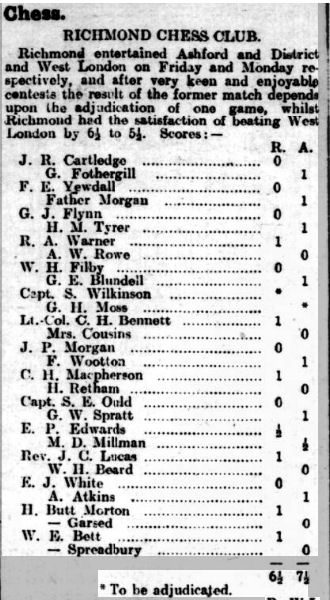

She certainly joined Barnes Village Chess Club in 1928. There she is on Board 4 in the local derby against Kew. You’ll find out more about her next time, but for the moment I’ll just point out that she was an important figure in the development of Ladies’ Chess in England.

Here’s a photo of George from towards the end of his life, impressively upright, still looking fit and active.

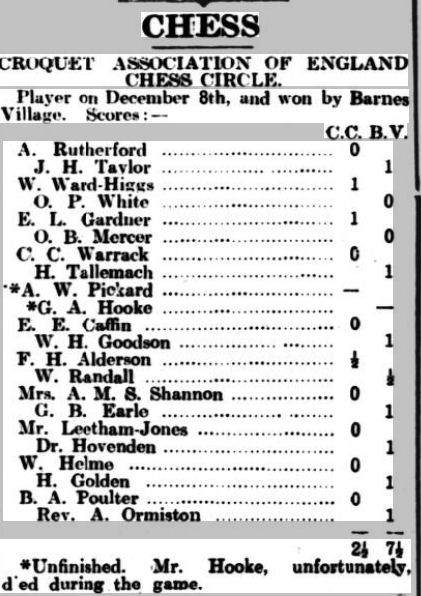

But by 1934 his health was starting to fail. He was no longer playing top board for his club, and, in this match from December that year, his opponent agreed to play their game at his house.

“Mr Hooke, unfortunately, died during the game”: having just won a piece he announced “That ends the game”, stood up and immediately suffered a fatal heart attack. It must have come as quite a shock to his opponent, Mr Pickard. I suppose, though, that George Archer Hooke died happy, doing what he enjoyed most, and in a winning position as well. “That ends the game” must be the perfect last words for any chess player. Very sad, but, at the same time, entirely appropriate.

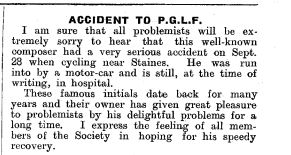

From elsewhere in the same issue of the Richmond Herald:

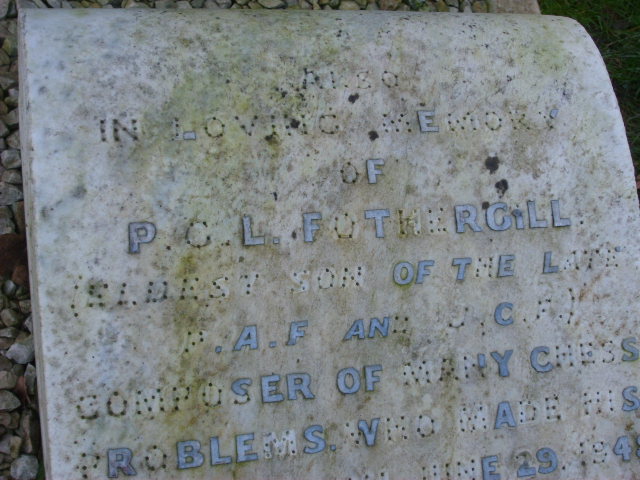

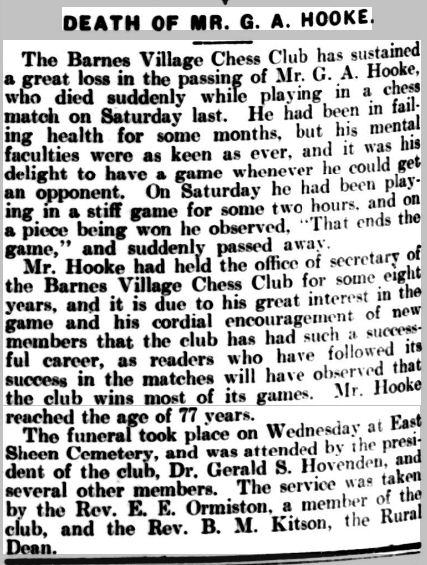

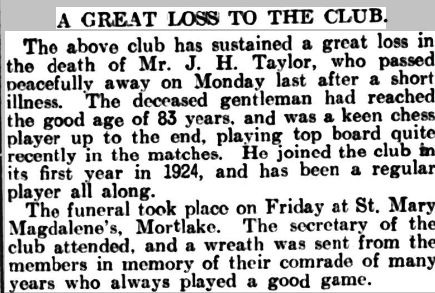

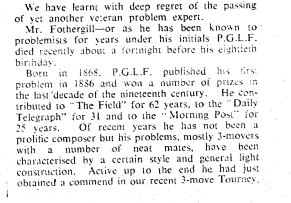

The British Chess Magazine published an excellent obituary the following month.

What a pity that the scores of most of his favourite games seem to be unavailable. I presume his scoresheets were thrown out many decades ago.

This list demonstrates, though, that he was a dangerous opponent for almost anyone in the country, even into his 60s. Although he wasn’t quite in the same class as some of the other players I’ve featured: George Edward Wainwright, William Ward and Thomas Francis Lawrence, he was still able to beat them and other players of master standard on his day. From the relatively small number of games I’ve been able to find, my impression is that he was a very talented player who played for the love of the game rather than with any ambition to reach the top, and who perhaps hampered himself by his tendency to choose suboptimal openings. I wouldn’t be surprised that, with an important job and five children, he thought he had better things to do with his time than study opening theory. And who could blame him.

He comes across as a man who was liked and respected by everyone who met him, as well as being a formidable chess player. A life well lived, I’m sure you’d agree.

After his retirement from the Board of Trade he took up a new hobby: genealogy, researching the Hooke family back over several centuries. This interest was passed on to his family, along with a lot of letters and photographs, but, as far as I know, not his chess scoresheets.

These are now in the possession of his great grandson Graham Hooke, whose lovingly curated family website has been an inspiration for these articles, and who was himself inspired by the story of George Archer Hooke. Graham has generously given me permission to use the photographs and letters quoted here.

I’d strongly urge you to visit Graham’s website: this is the best place to start.

It remains for me to tell you what happened to George’s children.

Mildred had a distinguished career in education, was Headmistress of Bradford Grammar School for Girls for 28 years, being awarded the OBE. Towards the end of her life, she married the aeronautical engineer Sir William Farren, a friend since university days. There’s a lot more information from Graham here.

Frances seems to have been the quiet one of the family, who devoted much of her life to looking after her parents. However, her life would take an interesting turn. The 1939 Register finds her in Hadley Wood, near Barnet, working as a maid for the family of (Charles) Herbert Lightoller, who had been 2nd Officer on the Titanic. You can find out a lot more about Herbert here and here. He was portrayed by Kenneth More in the 1958 film A Night to Remember.

Beatrix worked as a statistician, and also studied human remains from the Romano-British period, co-authoring a paper on the subject. She also took up chess, joining her aunt Alice in playing for Barnes Village from at least 1937 to 1948.

In this match against, I think, the Croquet Association, it’s notable that both teams fielded three ladies. Reginald Pryce Michell (his name here, as so often, misspelt) was one of England’s strongest players for many years, and his wife Edith Mary Ann (née Tapsell) would have been very well known to Alice Hooke from the world of ladies’ chess. With any luck they’ll be the subject of future Minor Pieces.

In 1950 Beatrix would marry her good friend and teammate Dr Gerald Hovenden, celebrated for being the oldest practicing GP in the country.

Ella, like Frances, never married, and, like Beatrix, also worked as a statistician, although, by 1939 she was working as a school secretary at Nottingham Girls High School, and had been evacuated to Ramsdale Park, a mansion seven miles outside the city.

The only one of George’s children to have a family was Cyril. He joined the Army, winning the Military Cross for gallantry in the First World War, and then serving in India. It was there that he married in 1926, and where his first (of two) sons, named George after his grandfather, was born nine months later. Graham provides a lot more information about his much loved grandfather here.

There will be more about the Hooke family next time, when I tell the story of George Archer Hooke’s chess playing sister Alice Elizabeth.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

EdoChess (George Archer Hooke’s page here)

chessgames.com

British Chess Magazine

Hooke Family History (many thanks to Graham Hooke)

Brian Denman

Gerard Killoran

Other sources as quoted above

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

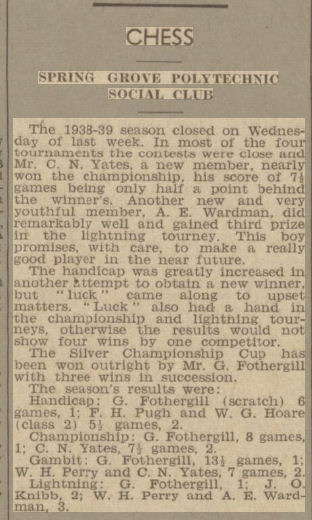

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.