From the book’s rear cover :

“Are you struggling with your chess development? While dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating simply does not want to move upwards? Spending loads of money on chess books and DVDs, but feeling no real improvement at all? No worries – the book that you are holding in your hands might represent a game changer! Years of coaching experience as well as independent research has allowed the author to identify the key skills that will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually constitutes the cornerstone of chess training, being no less important than memorizing opening theory, acquiring middlegame knowledge or practicing endgames. By studying this book, you will:- learn how to universally deal with any position you might encounter in your games, even if you happen to see it for the first time in your life, – have the opportunity to solve 90 unique, hand-picked puzzles, extensively annotated and peculiarly organised for the Readers’ optimal learning effect, – gain access to more than 300 pages of original grandmaster thoughts and advice, leaving you awestruck and hungry for more afterwards!”

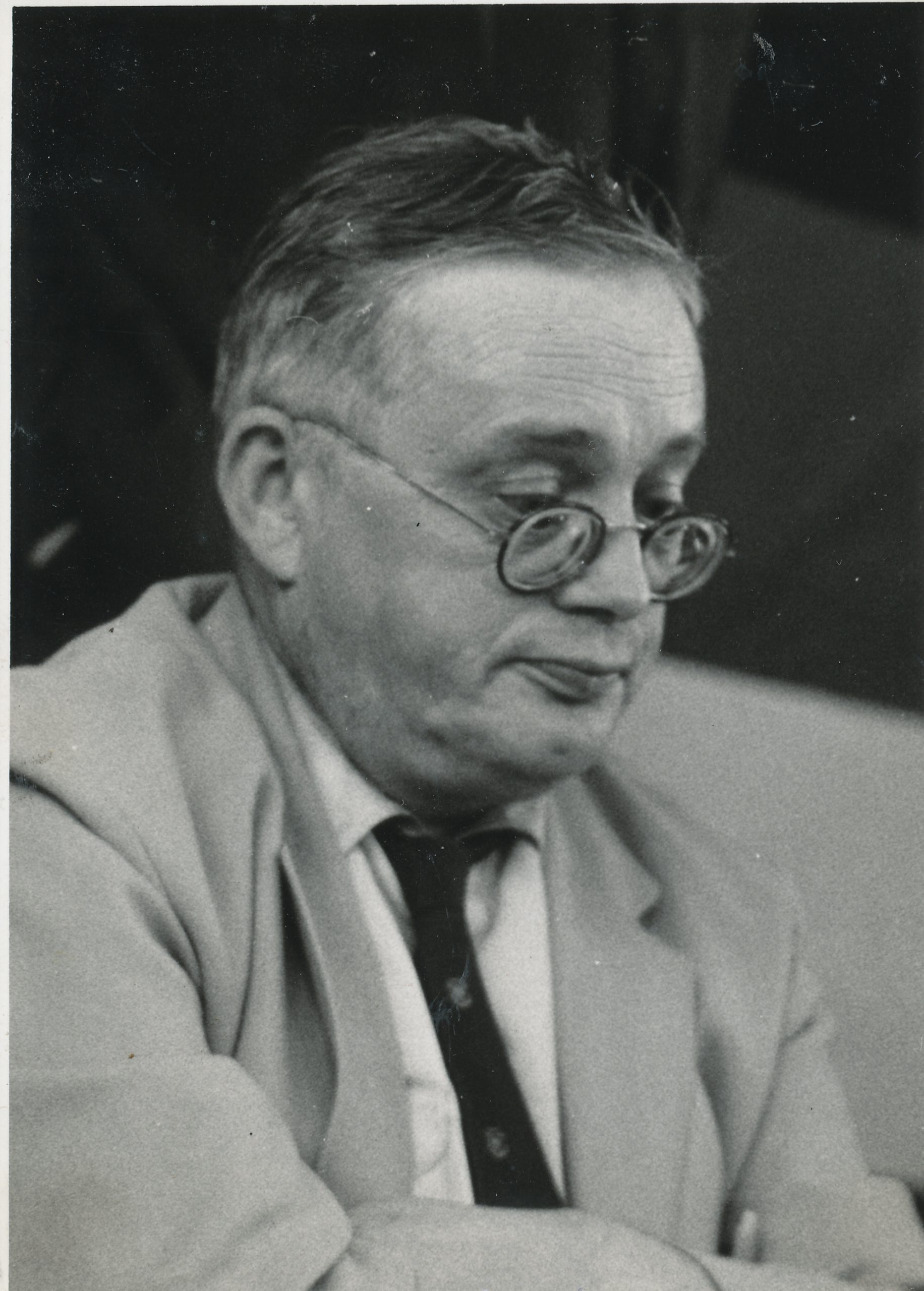

“Wojciech Moranda (1988), Grandmaster since 2009, rated FIDE >2600 in standard/rapid/blitz. Poland’s TOP 7 player (February 2020) and FIDE TOP 100 in Rapid (2018). Member of top teams from the German (Schachfreunde Berlin), Belgian (Cercle d’Échecs Fontainois) and Swedish (Visby Schackklubb) league. Captain of the third best Polish team (Wieża Pęgów) as well as the PRO Chess League team, The New York Marshalls. Professional chess coach, running his own chess school ‘Grandmaster Academy’ seated in Wroclaw (Poland), while training students worldwide, from California to Sydney. His other notable coaching experiences include i.a. working with the National Youth Chess Academy of the Polish Chess Federation (since 2012) and the Polish National Female Chess Team (2013). In his work as a trainer, Wojciech puts special emphasis on improving his students’ thought-process and flawless opening preparation.”

Time was when you knew what to expect from a puzzle book. With a few notable exceptions they tended to be ‘sac sac mate’ type of position.

21st century puzzle books are very different, and, at least for stronger players, quite rightly so as well. These days you can run a blundercheck on a bunch of games to identify the turning point, and then, with a careful selection of positions, produce a puzzle book in which anything might happen. A book of positions in which very strong players, even leading grandmasters, failed to find the correct plan. A book which exemplifies the wonderful complexity of contemporary chess, covering all aspects of the game: strategy as well as tactics.

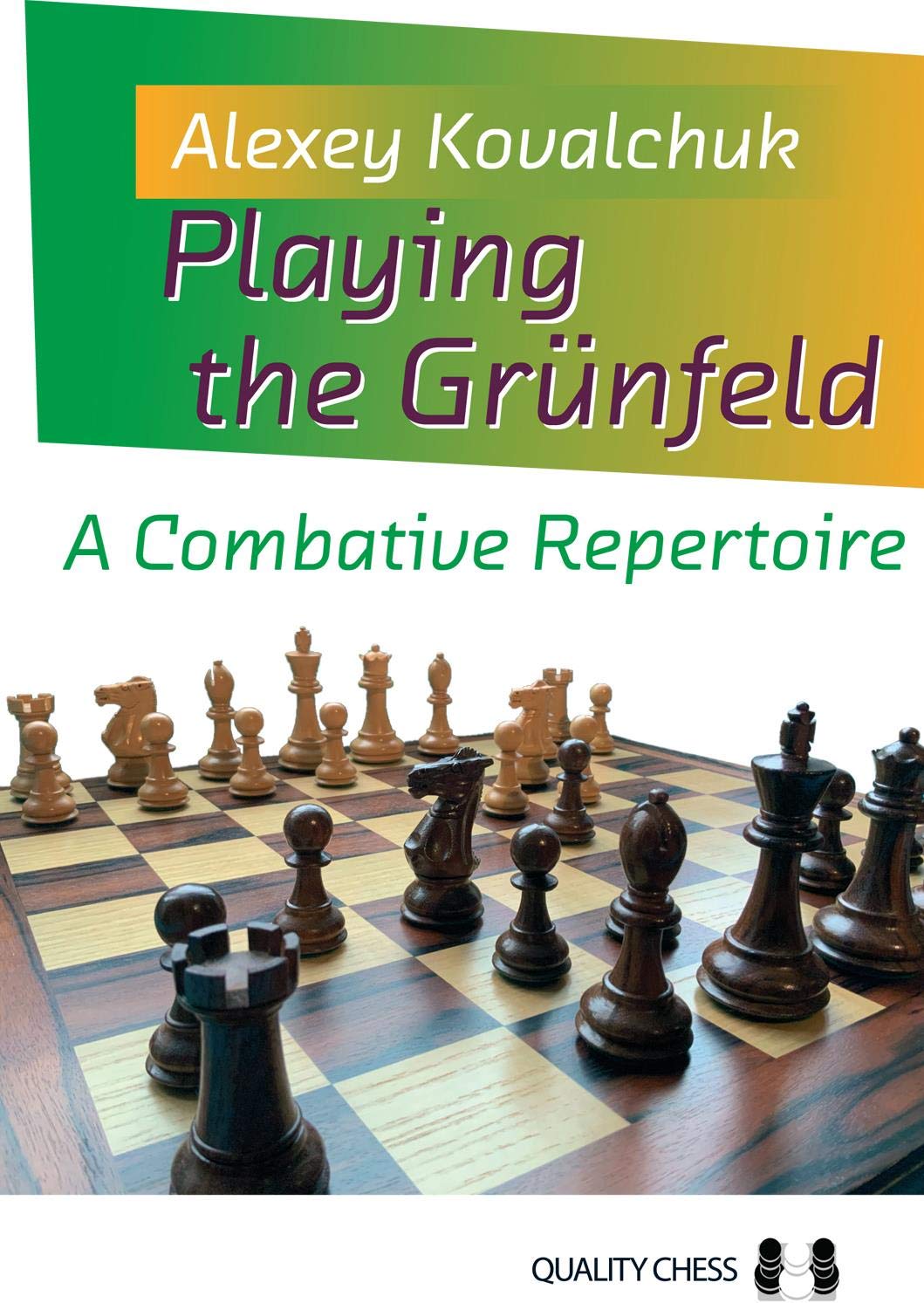

What we have here is very much a 21st century book written for strong and ambitious players. Indeed it seems in many ways very similar to this book from the same publisher: aimed at a similarly wide range of players and divided into three sections of increasing difficulty. One wonders if the authors of both books received a similar brief from Thinkers Publishing.

Let’s see what Moranda has to say for himself.

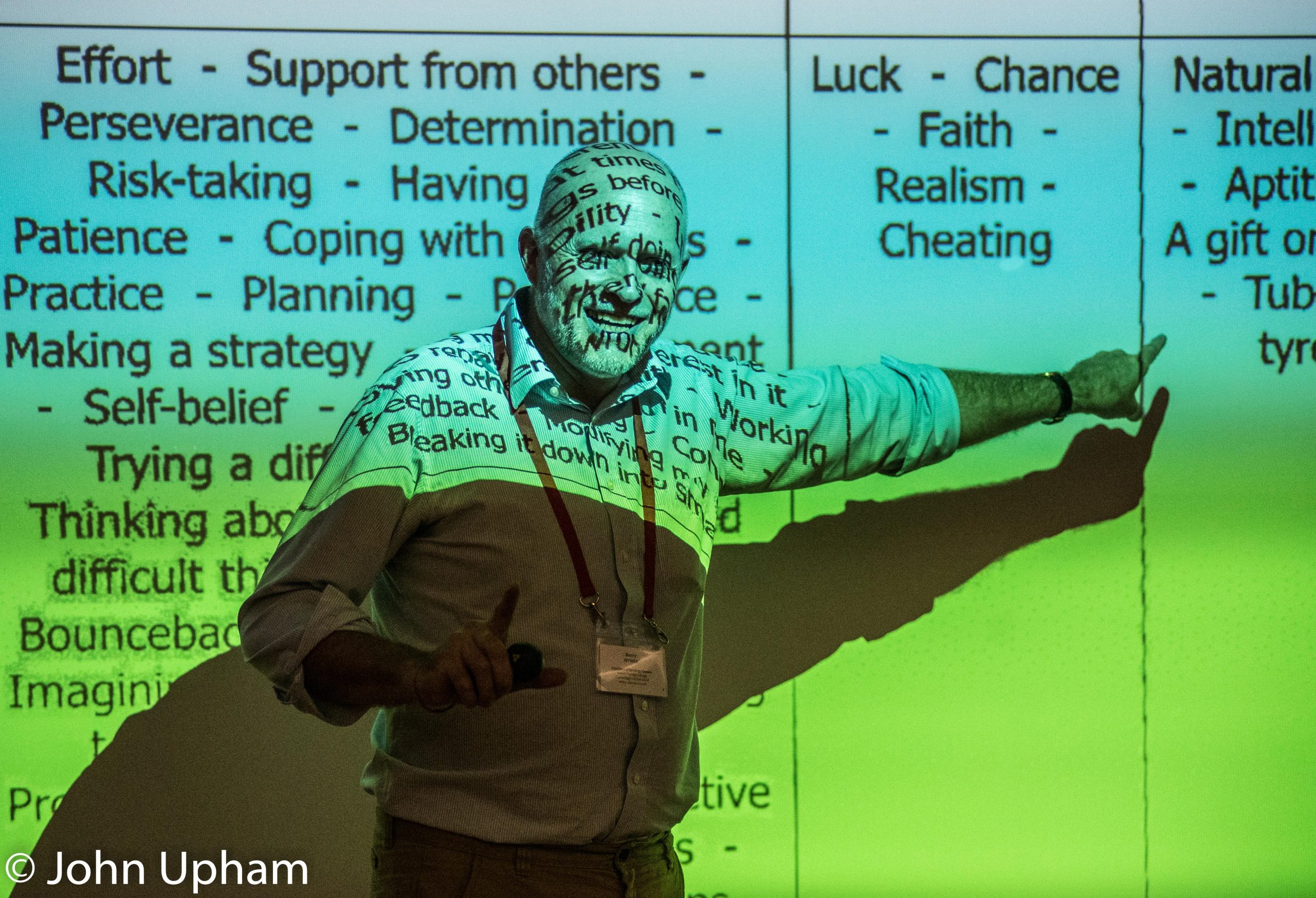

He identifies that his students have strategic problems in five areas:

- Anticipation & prophylaxis

- Attack & defense

- Coordination

- Statics & dynamics

- Weakness

Together, he considers these to be the basis of ‘Universal Chess Training’, “because knowing them will most certainly help you play a good move whether the position seems familiar or not”.

His book offers:

- Original content (he’s dismissive of books which repeat examples from the past, and also of books which haven’t been computer checked)

- Three levels of difficulty (the first part is for players of 1600-1900 strengh, the second part for 1900-2200 strength and the third part, presumably for 2200+ strength, where the questions demand ‘the highest level of abstract thinking’)

- Mixed exercises with no hints (so you have no idea what’s going to come next)

- Focus on what remained behind the scenes (so, instead of analysing the rest of the game he provides a possible conclusion given best play, which, he believes, provides more solid training material than the flawed continuation in the game)

There are 90 questions in total, 30 in each section. As a 1900 strength player the first two sections should be appropriate for me.

The first position in the book comes from Winterberg – Lubbe (Magdeburg 2019). You have to choose a continuation for White here.

Here’s how Moranda assesses the position:

“A brief review of the position reveals that a major backlash is coming in White’s direction. Black just needs to remove the queen from e6 and make way for the e7-pawn to go all the way to e5. As a result, White will not only be forced to concede space, but also have to spend time re-routing his minor pieces from their overly exposed outposts on d4 and h4. But this would by no means be the end of the story for White. With Black expanding his pieces would improve in quality, and it would only be a matter of time before they would shift their attention towards possible weaknesses present in White’s camp. Such a weakness is represented by the c5-pawn, which would be rather difficult to defend should the white bishop be compelled to step aside. At the same time, if White becomes too absorbed with maintaining control over the queenside, Black could very effectively switch to an attack against the white king due to his space advantage by means of …Nf7-g5. That is a grim prospect for sure but maybe there is an antidote to this looming chaos?”

I won’t tell you the answer: you’ll have to buy the book to find out.

Now look at the first question in Chapter 2:

It’s again White’s move in L van Foreest – Navara (Skopje 2018).

What do you think?

Moranda’s explanation again:

“At first sight it is hard to believe that this crazy position arose out of a Giuoco Piano which is a rather timid, manoeuvring opening. White has just embarked on a risky venture sending a knight deep into the heart of the opponent’s position. Black has responded with an offer to exchange queens, a perfectly viable solution from the perspective of limiting White’s chances of playing for an attack afterwards. The decision White should take is far from obvious as there are, at this point in time, five different discovered checks at his disposal. All of them look dangerous, but simultaneously none of them looks lethal enough. White would also love to include the remaining pieces into play, but he does not seem to have the time to do this. Notably, the proximity of the black queen to his own monarch constitutes an element White cannot easily ignore before furthering his attack. Thus I ask you dear reader, what should White do?”

A lot of words, a lot of explanations. The style is informal, often colloquial and sometimes amusing. “Do you ever have chess nightmares? You know, dreams of yourself taking part in a tournament and losing every single game or, even worse, finding yourself playing a game with the London System as White?” “At first glance this move is uglier than a Fiat Multipla.” You might like this sort of thing, or you might consider it out of place in a serious instructional book. Your choice. In general, though, I found the explanations excellent.

From a personal point of view, the 30 questions in the first chapter were pitched at just the right level for me: instructive and helpful. The second chapter, as well as the third, though, were much too deep. While I enjoyed reading the solutions and explanations I thought they were too hard for me to learn from. There’s a lot more than simply understanding the strategic ideas: you also have to calculate accurately to justify them: it was the calculation as much as the strategy that was too much for me. The book demonstrates clearly that tactics and strategy are inextricably entwined, and that, in today’s chess, positional sacrifices are an increasingly important weapon which ambitious players need to understand.

I’d have liked to have seen the openings of the games in question, and could have done with shorter explanations rather than the three or four pages of partly computer-generated analysis provided for each position, but, if you’re more serious about studying chess books than I am you may well disagree.

I read chess books mainly for enjoyment, and it’s 40 years or more since I had any real ambitions about improving my chess, so, although I’m the right strength, I’m not really part of the target market for this book.

Moranda is clearly an outstanding teacher at this level, and seems to come highly recommended online. The positions are well chosen and the ideas clearly explained: it’s obvious a lot of work and passion has gone into creating this book. The author is also an openings expert, seemingly favouring lines leading to positions which are both tactically and strategically rich: you’ve seen that he’s pretty scathing about the Giuoco Piano and the London System. If you prefer simpler methods of starting the game you will be less likely to reach the sort of positions featured here. While I consider the claim that it’s for anyone 1600+ to be a trifle optimistic, if you’re a strong and ambitious player (say 2000+, although anyone 1800+ will benefit from at least the first chapter) and you’re prepared to work hard, this book will undoubtedly improve your understanding of grandmaster chess strategy.

Richard James, Twickenham 2nd February 2021

Book Details :

- Hardcover: 352 pages

- Publisher: Thinkers Publishing; 1st edition (19 Nov. 2020)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9492510901

- ISBN-13:978-9492510907

- Product Dimensions: 17.78 x 2.54 x 24.13 cm

Official web site of Thinkers Publishing