We’re going to leave Twickenham for a bit, but don’t worry. We’ll be back there soon.

I’ve received a couple of requests for information on other players, both of whom (and they had a few things in common) seemed suitable for a Minor Pieces post.

I received an email the other day from my friend Ken Norman, who had come across some games from a Dr A Learner, who was active in Sussex chess in the 1960s, in an old copy of CHESS and, perhaps intrigued by the name, wondered if I could provide any more information. He also contacted Brian Denman, who knows almost all there is to know about Sussex chess history. Brian provided Ken with a games file which he was happy for Ken to share with me.

He seems to have been an interesting man who led an interesting life.

He was Dr Abraham Emanuel Learner, although he didn’t very often use his middle name and seems to have been known to his family and friends as Bill. He was born in London on 13 December 1904 and died in Eastbourne, Sussex on 16 February 1983. Some records spell the family name ‘Lerner’.

We can pick the family up in the 1911 census. His father, Arnold, was described as an ‘incandescent and clothing dealer’, born in Russian Poland, as was his mother, Deby, a dressmaker. Arnold and Deby married in the East London Synagogue in Mile End, right at the heart of the Jewish community, on 15 October 1904, only two months before Abraham was born. Another son, Mark, arrived in 1906. Soon afterwards they left London for Gateshead, in the north east of England, where they welcomed two daughters, Goldie and Sophie. It seems that all four siblings married outside the Jewish faith, and all of them emigrated to Australia, although Abraham, or Bill as we should perhaps call him, later returned to his home country.

Bill studied chemistry at Birmingham University, eventually earning a doctorate. During his post-graduate or perhaps post-doctoral work between 1927 and 1928 he wrote three papers on the structure of fructose and inulin along with Norman Haworth, who would win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1937, and, in two cases also with Edmund Hirst. I tried reading the papers but failed to get beyond the first paragraphs. If you want more information I’d suggest you contact my BCN colleague Dr John Upham, who knows all about this sort of thing.

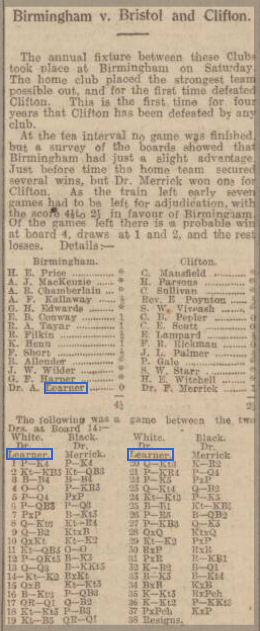

We first pick him up as a chess player in 1929. Here he is, playing on bottom board in a match between Birmingham and Bristol & Clifton, who fielded the great problemist Comins Mansfield on top board.

His loss against another doctor doesn’t appear in Brian’s games collection.

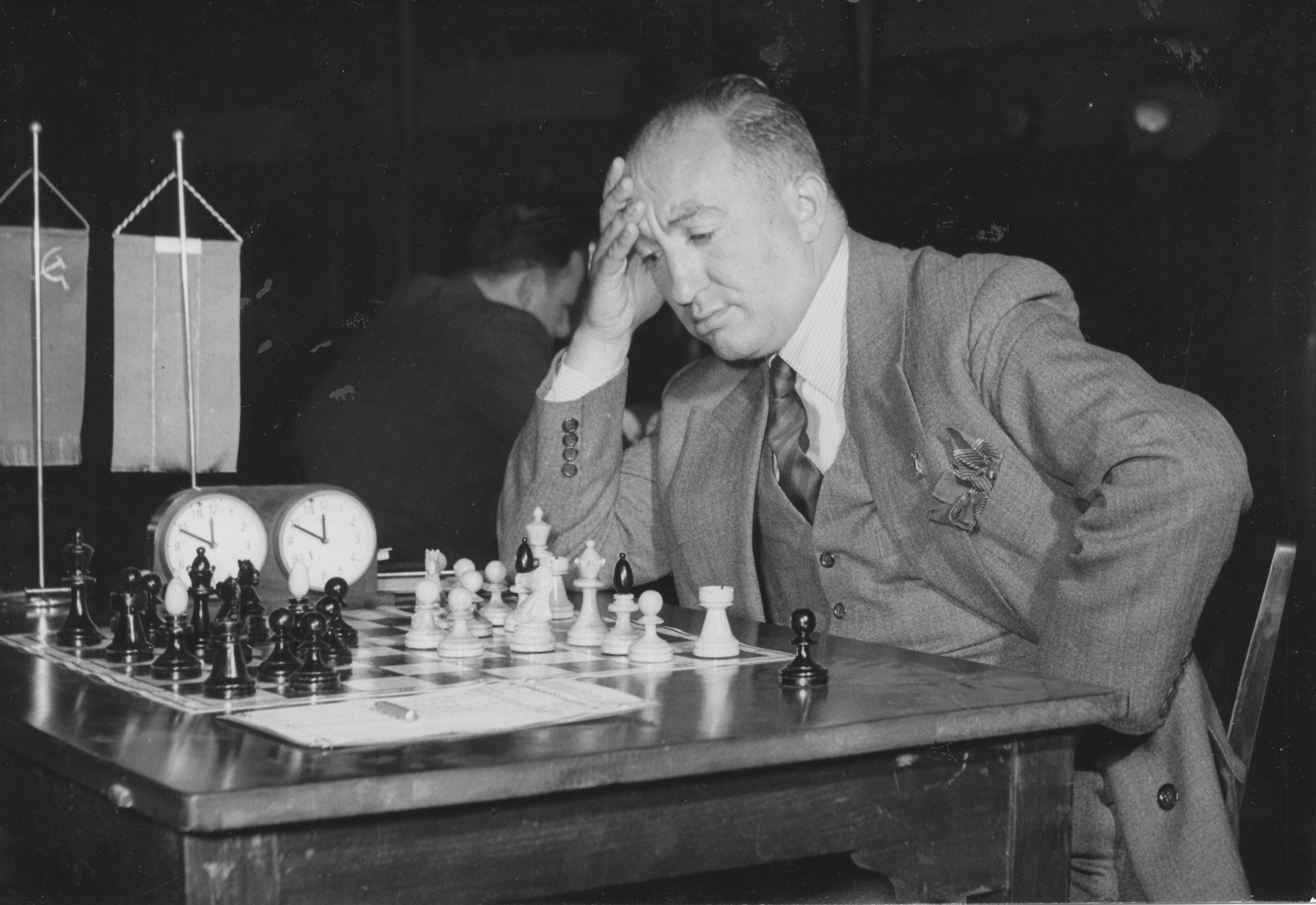

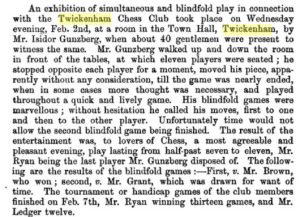

At about the same time he took part in a blindfold simul against George Koltanowski, winning with an attractive rook sacrifice. Kolty resigned, ‘seeing’ that a zigzag manoeuvre by the black queen would lead to a swift checkmate.

In 1933 Bill Learner married Elsie Harris in Birmingham. They would have just one son, named Arnold after his grandfather, who would predecease him.

During the 1930s Dr Learner continued to play for Birmingham, and for Worcestershire in county matches. In 1934, playing for his county against Oxfordshire, he was paired against another future Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Professor Robert Robinson, but lost that game. (Other chess playing, Nobel Prize winning chemists include Frederick Soddy and John Cornforth – might be worth a Minor Pieces series at some point.)

In this spectacular win Dr Learner played a dangerous gambit, offered a passive bishop sacrifice and finally gave up his queen for an Arabian Mate. But Black had a chance to turn the tables. After 17. Rae1? (the immediate Rf3 was winning) Qxc2, the second player has a winning advantage. A game well worth your time analysing, I think.

We can see from these examples that Bill Learner was a sharp tactician.

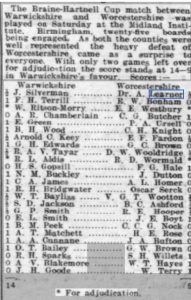

By 1935 he was on top board for Worcestershire. A county match against Warwickshire saw him up against another interesting opponent, future MP Julius Silverman. The result of this game was a draw. You’ll see a number of interesting names in both teams.

In a match against Leicestershire, his Stonewall Dutch scored a rather fortunate victory against Alfred Lenton (from whom you’ll hear a lot in future Minor Pieces) when his opponent, who shared 3rd place in the 1935 British Championship and 2nd place the following year, blundered in a winning position.

In 1937 Learner found himself on the wrong side of the law, being fined 10s for a speeding offence. I guess that’s what happens if you’re A Learner, driver. His address was given as Elmdon Avenue, Marston Green, Birmingham, very near Birmingham Airport.

Bill Learner won the Birmingham Post Cup in 1938, but when given the chance to prove himself at a higher level, in an international tournament organised by Ritson Morry the following year, he finished in last place. A dangerous attacking player, then, but perhaps not quite able (or ready) to compete against masters. By now, as you’ve probably worked out, World War 2 was about to break out, and that put his chess activities on hold.

The 1939 Register saw him at the same address, although Elmdon Avenue has become Elmdon Lane. (It appears to be Elmdon Road now.) He is a Managing Director, possibly of a paint factory. (The second line is not fully legible but we know, from his mother’s probate record, that he was a paint manufacturer. I guess the chemistry background would have come in useful.) Elsie and Arnold aren’t there: they’re up in the village of Ponteland, north west of Newcastle, staying with his sister Goldie and her family. Presumably they considered it safer there than in Birmingham. Bill had shown his love of the area by naming his house Ponteland.

He turned out for a club match in 1940, but then nothing until 1945, when chess resumed after the war, and he resumed where he left off, playing for Birmingham and Worcestershire.

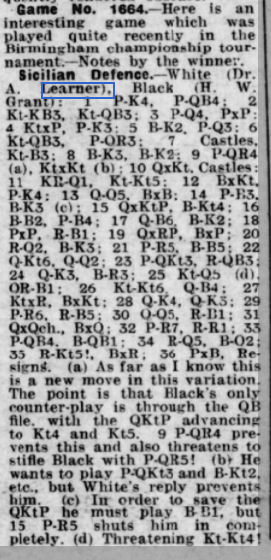

Here he is providing brief annotations for a win against an opponent I assume to be the problemist Herbert W Grant.

Then, at some point he emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, where he took part in the 1948-49 championship. He finished 13th out of 14 on 4½ points (Cecil Purdy was the winner) but did manage to defeat Maurice Goldstein, who blundered into a mate when he could have traded off into a winning ending.

By 1952 he was Vice-President of Melbourne Chess Club and wrote a long (but not especially interesting) article about the delights of his favourite game.

What was he doing in Melbourne when he wasn’t playing chess? In the 1949 and 1954 electoral rolls he was a manufacturer, in 1958 and 1963 a director. Was he still manufacturing paint? Perhaps he was working with his brother: Mark owned a large textile importing warehouse right in the city centre.

He continued to be active in Melbourne chess until 1963, when he decided to return to England for his retirement, settling on the south coast and soon getting involved in Sussex chess. Playing at Bognor Regis in 1964 he came up against a man who would, the following year, become Yugoslav champion and an International Master. Here’s what happened.

A pretty effective demolition of a strong opponent, I’d say.

Dr Learner had a habit of winning extremely short games. Here are two examples.

He continued playing chess until at least 1970 before deciding to hang up his pawns. The last game we have available is a draw against Brian Denman from a match between Hastings and Brighton. His 1970 grade was 191, down from 195 in 1969 and 201 in 1968, with his clubs given as Hastings and Eastbourne.

His address at his death (just three months after his wife) was given as High Bank, Borough Lane, Eastbourne, and his probate record tells us his estate was worth £102,858. He’d done pretty well for himself, in business as well as in chess.

Dr Abraham Learner was a strong county player, a dangerous tactician who, on a good day, could beat master standard opponents.

His career of more than four decades can, like Caesar’s Gaul, be divided into three parts: in Birmingham from the late 1920s to the late 1940s, in Melbourne until the early 1960s and finally in Sussex.

Players like him are the backbone of club and county chess.

My thanks to Ken for his interest in Dr Learner and to Brian for providing the game scores. If there are any other British chess players you’d like me to investigate do get in touch.

Other sources consulted:

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.findmypast.co.uk

www.newspapers.com

BritBase