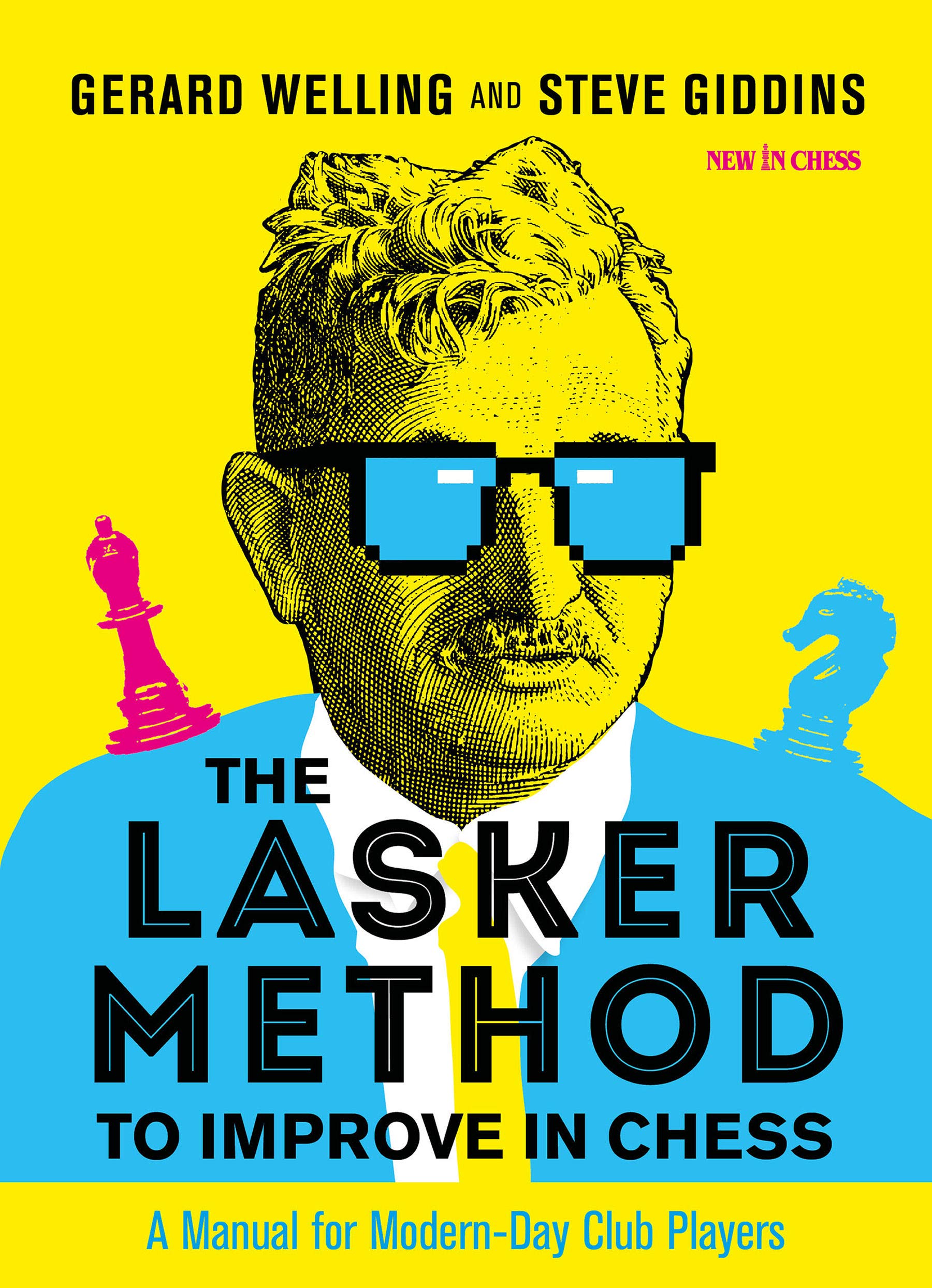

The Lasker Method to Improve in Chess : Gerard Welling and Steve Giddins

From the book’s rear cover :

“Many club players think that studying chess is all about cramming as much information in their brain as they can. Most textbooks support that notion by stressing the importance of always trying to find the objectively best move. As a result amateur players are spending way too much time worrying about subtleties that are really only relevant for grandmasters.

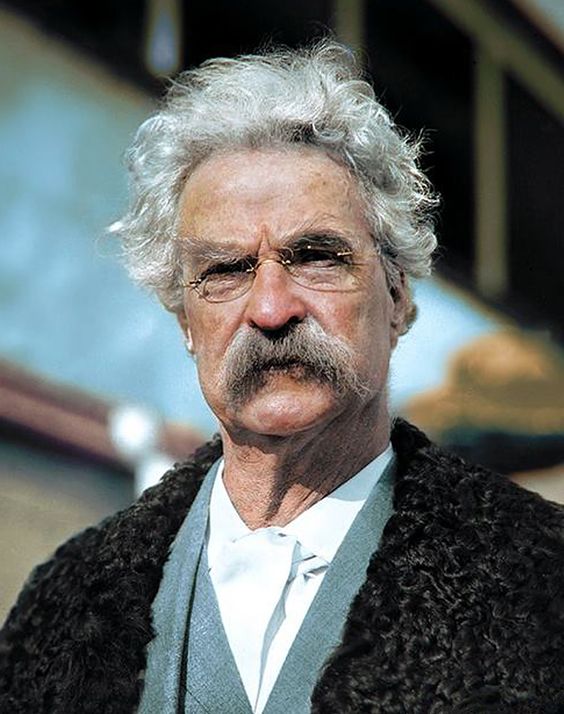

Emanuel Lasker, the second and longest reigning World Chess Champion (27 years!), understood that what a club player needs most of all is common sense: understanding a set of timeless principles. Amateurs shouldn’t waste energy on rote learning but just strive for a good grasp of the basic essentials of attack and defence, tactics, positional play and endgame play. Chess instruction needs to be efficient because of the limited amount of time that amateur players have available.

Superfluous knowledge is often a pitfall. Lasker himself, for that matter, also studied chess considerably less than his contemporary rivals. Gerard Welling and Steve Giddins have created a complete but compact manual based on Lasker’s general approach to chess. It enables the average amateur player to adopt trustworthy openings, reach a sound middlegame and have a basic grasp of endgame technique. Welling and Giddins explain the principles with very carefully selected examples from players of varying levels, some of them from Lasker’s own games.

The Lasker Method to Improve in Chess is an efficient toolkit as well as an entertaining guide. After working with it, players will dramatically boost their skills, without carrying the excess baggage that many of their opponents will be struggling with.”

“Steve Giddins is a FIDE Master from England, and a highly experienced chess writer and journalist. He compiled and edited The New In Chess Book of Chess Improvement, the bestselling anthology of master classes from New In Chess magazine. In 2019 Giddins published, together with Gerard Welling, the highly successful chess opening guide Side-Stepping Mainline Theory (ISBN 9789056918699).”

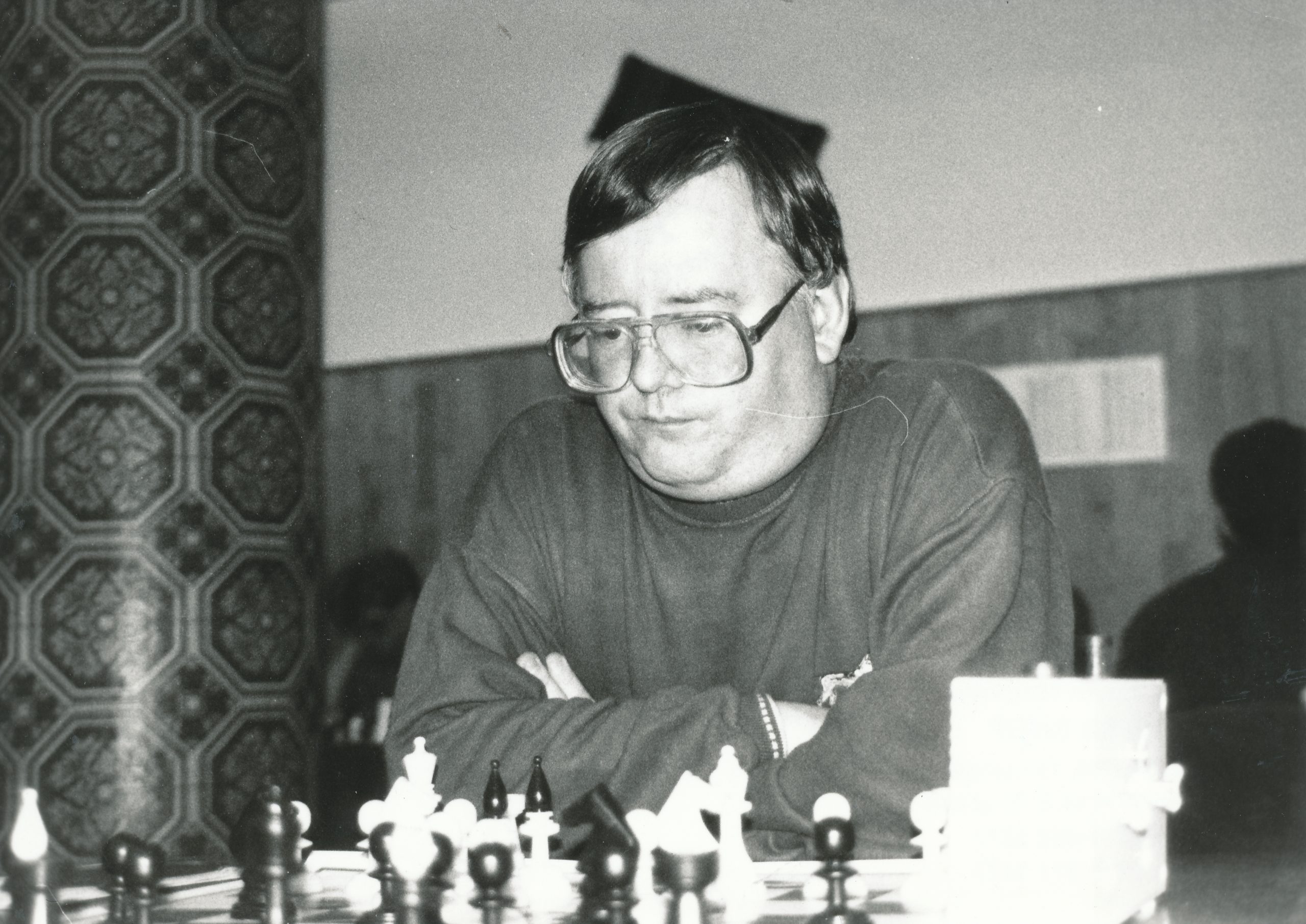

“Gerard Welling is an International Master and an experienced chess trainer from the Netherlands. He has contributed to NIC Yearbook and Kaissiber, the freethinker’s magazine on chess openings. In 2019 Welling published, together with Steve Giddins, the highly successful chess opening guide Side-Stepping Mainline Theory (ISBN 9789056918699).”

Most instructional chess books fall, broadly speaking, into one of two categories.

There are those, often written by younger players, which emphasise studying recent grandmaster games, teach openings by encouraging you to memorise long variations, provide annotated games with reams of computer-generated lines, offer very hard puzzles from top level competitions, and sometimes suggest you devise a timetable for study, setting aside a certain number of hours a day for opening study, tactics training, online games and so on.

Then there are books, usually written by older and, perhaps, wiser authors, very often not of GM strength, but with decades of experience both playing and teaching, who understand that most amateurs have a limited amount of time available. They recommend studying the classics, keeping things simple, choosing openings which are easy to learn, understanding ideas and plans, mastering the ending.

You won’t be surprised to learn that my sympathies are, with some reservations, more with the latter camp. And that’s what we have here.

You might not like the vivid yellow and blue cover, with our hero Manny Lasker wearing cool shades, but, putting that aside, let’s dive in.

The introduction is always a good place to start, so that we can see the authors’ aims in writing the book. In this case, they have much to say which I found particularly interesting, or perhaps just confirming my prejudices.

The amateur player has limited time for chess play and study, but still likes to practice his ‘major hobby’ as well as he can, and thus would like to base his game on reliable premises. He ideally wants to play trustworthy openings, and reach a sound middle game, and would welcome a basic grasp of endgame strategy, but often lacks the time to work on this.

Some amateurs, certainly, most, quite possibly, but not all. If you prefer to play dodgy gambits in the hope of winning a few quick brilliancies, this may not be the book for you.

You might recall, that a few years ago, John Nunn wrote a text book based on Lasker’s games. How does this book differ?

In the present book, we aim to do something completely different: we emphasise the specifically Laskerian approach and how it can be used by the average club player. Lasker emphasised most of all playing by understanding and general principles, with minimum rote-learning (especially of openings). This is perfect for the average amateur player, who wants to be able to maintain a good standard of play without relentless homework.

And again:

Nobody can possibly play the best moves all the time. Mistakes are inevitable and they are what decide games, so his (Lasker’s) aim was to try to induce more mistakes from the opponent than from ourselves. So, for example, for the average player, playing a position which he understands and feels comfortable in is more important than playing an objectively superior position that he doesn’t understand and doesn’t feel comfortable in, because he is more likely to go wrong in the latter.

If you, like me, are broadly sympathetic to this view of chess instruction, then, you’ll almost certainly enjoy this book. Younger and more ambitious readers, who prefer to study hundreds of ‘trainable variations’ on an online platform might have a different opinion.

Chapter 1 is very brief, looking at Lasker’s general ‘common sense’ chess philosophy. His Manual of Chess dates from 1925. Almost a century later, chess is very different, but do his principles still stand up? The authors believe they do.

Chapter 2 considers the three principles of positional play. 1: the principle of attack: if you have the advantage you must seek ways of exploiting it. 2: the principle of defence: as your opponent will attack your weakest point, you must defend it. 3: the aim of your actions should be proportionate to the size of your advantage.

In real life, of course, it’s not always as simple as that. You might, for example, have an extra pawn but a weakened king-side or a less effective minor piece. Imbalances of this nature are also important.

Chapter 3 looks at endings. The authors explain the need to know theoretical endgames, and offer a few examples from Lasker’s games.

In this position, for instance, from the first game of his 1911 World Championship match against Schlechter, he managed to draw the game by giving up a second pawn with 54… Re4! 55. Rc5 Kf6 to activate his pieces.

We move on to Attack in Chapter 4. Only the first game here was played by Lasker. The others, mostly unfamiliar, illustrate the point that if your opponent’s king is insufficiently well defended you sometimes need to strike quickly before he has time to bring up the reserves. The openings, though, are often not those you’d associate with Lasker. A small point here: in game 12, where Lodewijk Prins played the eccentric 1. e4 c6 2. b4, the black pieces were handled by Rupert, not Robert Cross.

The authors prefer verbal explanations to variations, and that can be seen in the instructive note here (Sosonko – Eising Mannheim 1975), where Black played 30… Nxg2!

The Australian master and didact C.J.S. Purdy warned that tactics dominate the game and can come out of nowhere, even in positionally lost situations. We believe it is a matter of formulation, because if there are correct tactics available, then, by definition, the position is NOT strategically lost. Lasker formulated this in a clear way, where he mentioned ‘a large superiority of force in a quarter where the opponent has an important weakness’.

Well, yes, but we’ve all lost games by blundering and allowing a tactic in strategically winning positions.

After Attack you’d be right to expect Defence. Two of the four examples here come from Lasker’s games. We’re often taught to seek counterchances or to enter swindle mode, but here the authors demonstrate that, in some cases, just sitting tight and trying to hold everything is the best policy.

Next, we have a short chapter on knights and bishops. Lasker had a particular appreciation for positions where knights outshine bishops, and here we learn about Giddins’ friend Michael Cook, one of the inspirations behind this book: a Lasker admirer who also favours equine manoeuvres.

The following chapter is perhaps unexpected: Amorphous Positions. Restrained but resilient formations without weak links but with potential energy. We first look at a couple of Lasker games where he placed a bunch of pawns on the third rank before moving on to meet another amateur, in this case a Dutch player named Philip du Chattel, who, when playing black, seemingly favoured Nh6 on move 1 or 2. I’m not sure this is something Lasker would ever have considered.

(As an aside, Welling himself is a chess maverick, and his latest book has been co-written with English maverick IM Mike Basman. I suspect there’s an interesting book to be written about strong (say 2200+) players who favour offbeat openings.)

Finally in this chapter we see some games played by Canadian maverick GM Duncan Suttles, who also preferred non-committal openings of this nature.

We’ve now, travelling backwards from the ending, reached the opening, and in Chapter 8 the authors propose a repertoire based on Lasker’s principles.

At amateur level, especially, most games are decided by tactical opportunities and it is of no relevance at all whether one side or the other has a quarter of a pawn’s advantage after the opening. The important thing is just to reach a playable position, with the pieces developed and the king safe, preferably without significant pawn weaknesses.

(Another aside: the authors previously collaborated on a repertoire book which proposed playing a Philidor/Old Indian setup with both colours. Here we have something very different.

As Black, we’re going to defend classically. We’ll meet 1. e4 with e5, playing the Steinitz Defence (with 3… Nf6 followed by 4… d6) against the Ruy Lopez. Against the Italian Game we’ll play 3… Bc5, although we’ll need some concrete analysis. 4… d5!? is suggested against the Evans Gambit, but Greco’s 7. Nc3 in the old main line is dismissed rather too hurriedly. If you don’t like this, 3… d6 is an alternative. We’re also provided with safe and sensible lines against White’s alternatives. We’ll decline any gambit, meeting the King’s Gambit with 2… Nf6!? and the Danish Gambit with 3… d5. Against d4, likewise, we’ll opt for 1… d5, playing the Orthodox Defence to the Queen’s Gambit. Again, common-sense lines are offered against the main line, the Exchange variation, the Bf4 variation and the Catalan. But something seems to be missing here: there’s nothing about the currently popular and annoying London System, not to mention the Colle or Torre. The English and Réti are dismissed in a column and a half (1… e6 and 2… d5) and other first moves aren’t mentioned at all.

With White, we’ll play 1. e4. Against 1… e5 we’ll play the Ruy Lopez, but, following Lasker’s predilection for knights, we’ll trade on c6 at the first opportunity. In the Exchange variation proper we’re advised to play 5. Nc3 rather than O-O.

If Black offers the Petroff instead we’ll head for the ending with 5. Qe2. We’ll play the Closed Sicilian, with our king’s knight on the flexible e2 square. Against the French and the Caro-Kann you won’t be surprised to hear that we’ll trade pawns on d5. Again, this seems incomplete: there’s no recommendation against any other defence to 1. e4.

What do you make of this? It makes sense as far as it goes, but it’s certainly not for everyone. You’ll need a lot of patience as well as endgame skill to enjoy it. It might, of course, be exactly what you’re looking for. You might, as one often does with repertoire books, like some, but not all the suggestions.

Chapter 9 is the meat of the book: games for study and analysis based on the openings recommended in the previous chapter, 41 of them in total, well selected (many deeply obscure so you almost certainly won’t have seen them before) and well annotated. The young guns who tell you to study recent GM games will be horrified to see that most of the games are from the last century, although Carlsen makes an appearance playing the Exchange French. Welling and Giddins are not the first authors to comment on the similarity between Lasker’s and Carlsen’s approach to chess.

You won’t find many short brilliancies, but this is an exception:

Black chooses a modest opening formation giving White a slight advantage, but this game demonstrates how easy it is for the first player to overreach in this type of position.

We also meet Michael Cook again, and see two of his wins against the Ruy Lopez, one of them against my old friend Malcolm Lightfoot. I found the ending of the other game particularly interesting.

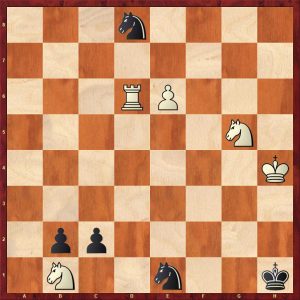

This is from a 1980 county match where Cook is black against R Bristow. Like many of my generation, I was brought up on Basic Chess Endings and led to believe that bishops were stronger than knights in endings with pawns on both sides of the board. Of course this is very often the case, and there’s an excellent example earlier in the book.

This position is objectively drawn, but it’s Black who can press for the full point.

The game concluded 29. Kg1 Nd6 30. g3 f6 31. Bb4 Nb5 32. Kf2 Kf7 33. Ke3 Ke6 34. Ke4 f5+ 35. Kd3 Kd5 36. Bc3 g6 37. Be5 h5 38. Bb2 Kc5 39. Bc3 Nd6 40. Bd2 Ne4 41. Be1 Kd5 42. Ke3? (a3 would have held) Kc4 43. Ke2 Kd4 44. Bb4 h4 at which point time was called and the adjudicator (yes, that’s how we played chess 40 years ago) awarded Cook the point. The authors claim that after 45. Kf3 hxg3 46. hxg3 Nc3 47. a3 Kc4 Black wins, but Stockfish isn’t convinced after, for example, 48. g4.

The authors comment:

Within reason, the objective assessment of the position does not matter that much, when it is just a matter of a slight plus one way or the other – what is much more important is knowing what you’re doing and understanding that the white advantage, if any, is relatively small.

… and:

An additional point, as we have seen, is that the white player will frequently overestimate his advantage and play too ambitiously, often just because ‘the books’ say this Steinitz Defence is not really very good. Just as Lasker said, he preferred the side ‘which has kept back his forces a little’. so deliberately heading for a position where one knows one is objectively slightly worse, but also knows that the disadvantage is small and manageable, and where one also knows how to handle the position, is often a very effective way to play for a win.

Interesting and thought-provoking, I think, and certainly a very different philosophy from the maximalist approach espoused by many authors of instructional manuals. It’s certainly not the only way to play chess, but it might just be for you. An awareness that your opponents might be taking that approach could also be useful.

Finally, there’s the almost obligatory puzzle section. We have 50 puzzles, split into easy, intermediate and difficult, taken, with one exception, from the games of the authors and their hero.

Again, they have some helpful insights to share:

Talking about the experience of analysing with a much stronger player:

The other chap just seems to ‘see’ things so quickly, noticing immediately little tactical tricks which escape the lesser player altogether, or else take him much longer to spot. And we are mainly talking not about spectacular sacrificial combinations, but about routine tactical ideas, 2-3 moves deep, on which so much of a chess game hinges.

Indeed. At club level it’s precisely this which decides most games.

So how does one acquire such ability? Well, as with most things in life, talent is obviously a factor, but hard work and regular practice is crucial. Tactical ability and alertness is rather like physical fitness – when you start from a very low level, a lot of work is needed to build yourself up to a certain level, but once you are there, 15-30 minutes’ exercise a day is all you need to maintain that level.

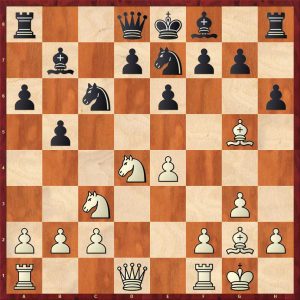

Here’s one of the intermediate puzzles.

In this position White played 24. Nxc4. Is this a blunder? You’ll find the solution at the foot of the page.

It’s often interesting when reading a book with two authors to try to guess which author was primarily responsible for which chapter. (You might like to do this with The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict.) Welling (eccentric openings) and Giddings (safe and simple openings) seem to have slightly different chess philosophies, but they converge with the idea that it doesn’t matter if you’re slightly worse: just that have more understanding of what’s going on than your opponent.

If you’re young and ambitious you might turn your nose up at books of this nature, but club players rated anywhere between, say, 1600 and 2200 who would like to improve their chess in between family and work commitments may well find this book inspirational even though they might not agree with everything the authors say, and might well find some or all the repertoire recommendations don’t suit.

I really enjoyed reading it, and felt I learnt quite a lot as well. I’ve always believed that you’ll benefit more from studying games played by someone 200-300 points stronger than you than you would from top grandmasters. Looking at their games you can think “Yes: I could learn to play like that”, and as Michael Cook, for example, was, at his peak, 200 points or so stronger than me, I could learn a lot from his games. My frustration was that the book seemed incomplete, and, as a result, perhaps not always totally coherent. There were a couple of signs that it might have been edited down from something much longer at the request of the publisher, but of course my hunch could well be incorrect.

The book is well written and produced to this publisher’s customary high standards. It may not be a book for everyone, but if you’re part of the target market you don’t need to hesitate. There are many fascinating and provocative insights which will encourage you to look at chess in a different way.

Solution to puzzle (Giddins – Carlier Antwerp 1993): 24. Nxc4 isn’t a blunder because after 24… Bxc4 he has the decisive blow 25.Rb6! Qxb6 26. Re6+ Kg8 27. Rxb6.

Richard James, Twickenham 4th May 2021

Book Details :

- Paperback : 240 pages

- Publisher: New in Chess (16 Mar 2021)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9056919326

- ISBN-13:978-9056919320

- Product Dimensions: 17.25 x 1.55 x 23.67 cm

Official web site of New in Chess