Happy Birthday IM Dagne Ciukšyte born on this day (January 1st) in 1977.

Here is her Wikipedia entry

Happy Birthday IM Dagne Ciukšyte born on this day (January 1st) in 1977.

Here is her Wikipedia entry

😐😕😱 ‘The Moves That Matter’ – Jonathan Rowson (Bloomsbury 2019). HB. p 352. cp £20.

Subtitled ‘A Chess Grandmaster on the Game of Life’, this is a chess publication like no other. To draw comparisons I would have to wander into other fields which is hardly the idea hereabouts and beyond my experience anyway. Having spent about seven or eight hours with this remarkable tome what follows is more of a reaction than a deadpan review.

When I bought my copy in Waterstone’s in Reading the lady said it was not shelved with other chess books and I am not surprised. It merits its own glass case as this is special but not to my taste. How the sales will pan out I have no idea. I imagine quite well as with ‘The Rookie’ by Stephen Moss, also a Bloomsbury. Moss’s book was an outsider’s view looking inwards. Rowson writes as an insider yet jumps (outside!) around seemingly not getting over himself. International travel, tournament success, marriage, maturity and great academic success have failed to bring him the answers he seemingly requires, the reader will bleed with him. His pain is now ours.

In a closing chapter, putting flesh on very intricate bones, he gives 19 annotated games. No diagrams that I spotted but should that matter? Here is philosophy offered in scholarly form, a life journey, as all the best autobiographies try to be. But I just was not entertained or instructed. It did, however, tell me all about this chess master.

The author is a largely retired Scottish Grandmaster.

James Pratt

Basingstoke, 2020

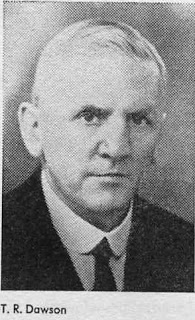

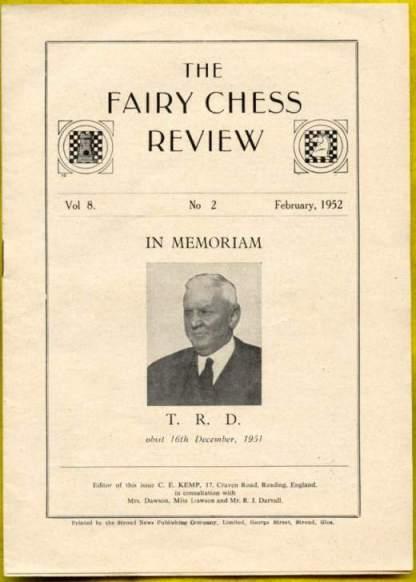

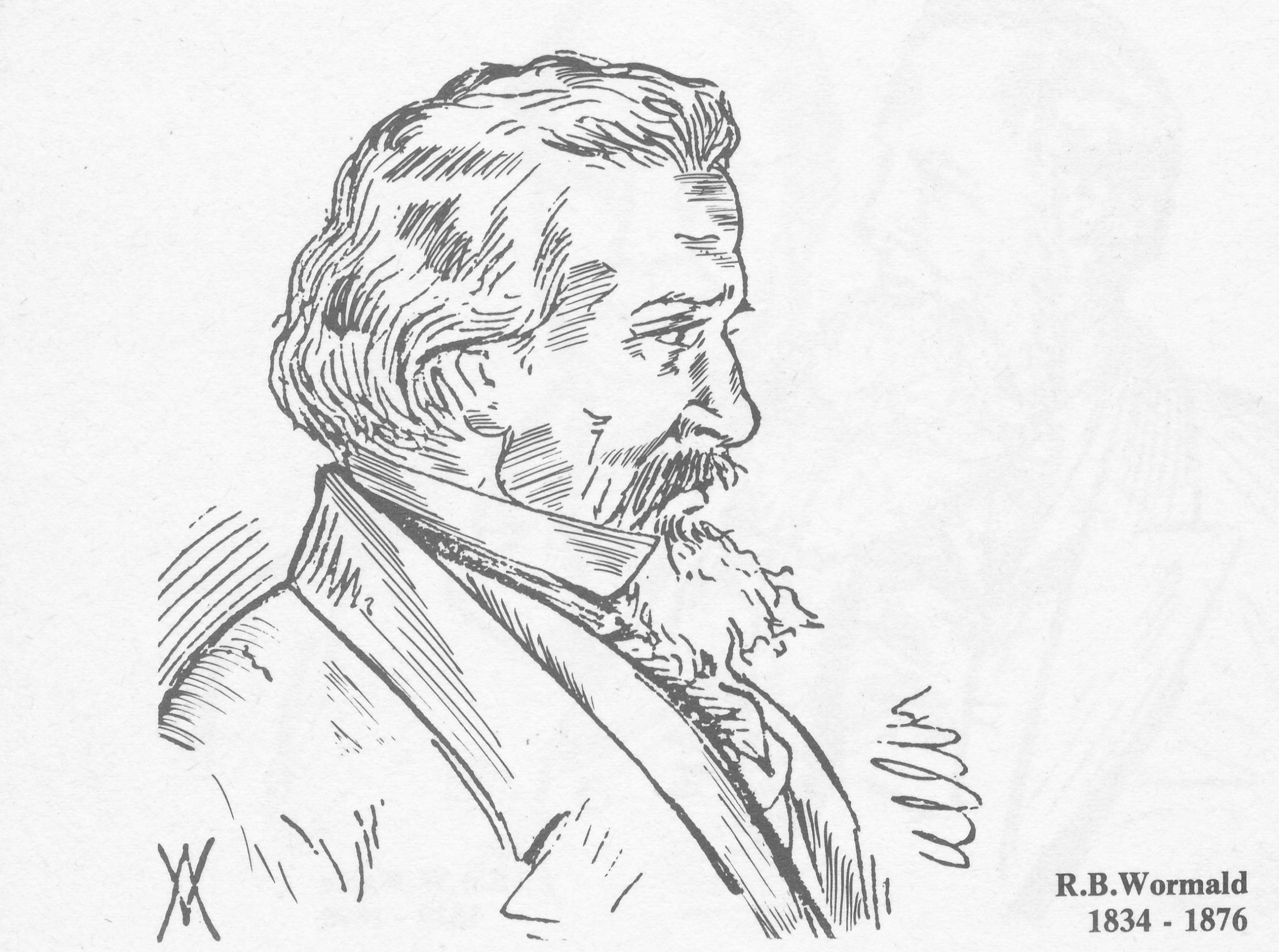

We remember Thomas Dawson who passed away seventy years ago on Sunday, December 16th, 1951.

He was also known by the pseudonym T. Dyke Robinson (we are looking for a primary source for this)

Thomas Rayner Dawson was born on Thursday, November 28th 1889 in Leeds, Yorkshire to Henry and Jane Dawson (née Rayner).

The early history of TRD and his family has been meticulously researched by Yorkshire chess historian, Steve Mann. We recommend you visit this page to discover the detail.

According to Edward Winter in Chess Notes TRD lived at the following addresses :

From The Oxford Companion to Chess (OUP, 1984 & 1996)by Hooper & Ken Whyld:

“English composer, pioneer of both fairy problems and retrograde analysis. His problems in these fields form the greater part of his output (about 6,500 compositions) and are better remembered than his studies and orthodox problems. For fairy problems he invented new pieces: grasshopper (1912) LEO (1912), NEUTRAL MAN (1912) NIGHT RIDER (1925), and VAO (1912); he codified new rules such as the maximummer (1913) and various kinds of series-mover; and he used unorthodox boards.

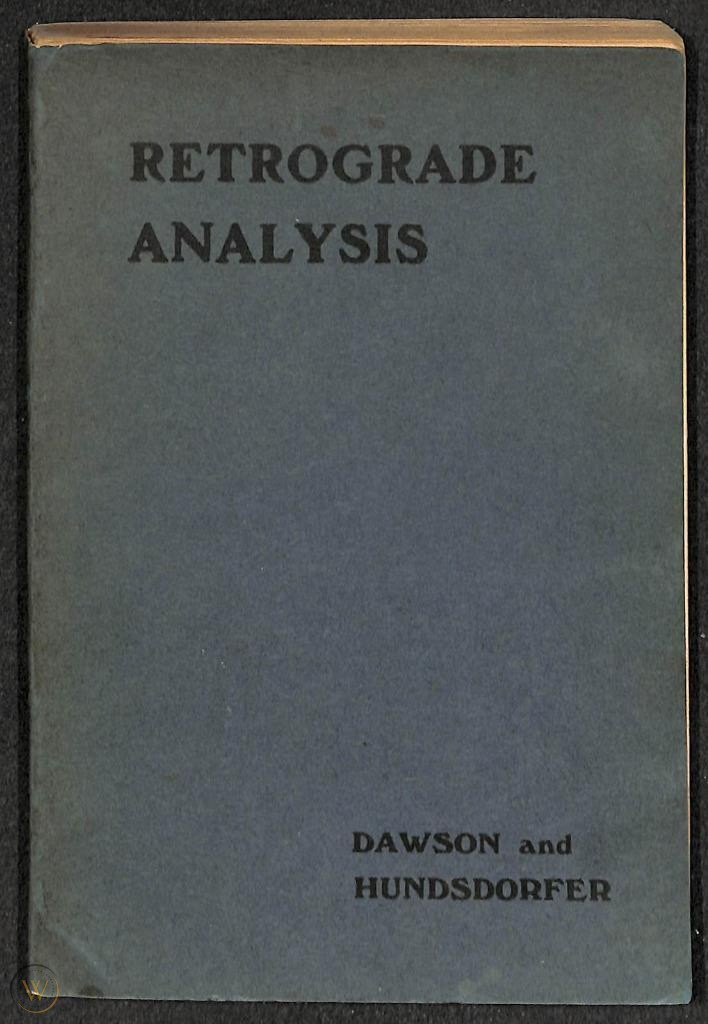

In 1915 he wrote Retrograde Analysis, the first book on the subject, completing the project begun several years earlier by the German composer Wolfgang Hundsdorfer (1879-1951).

From 1919 to 1930 Dawson conducted a column devoted to fairy problems in the Chess Amateur, In 1926 he was a co-founder of The Problemist , which he edited for its first six years and he founded and edited The Problemist Fairy Supplement (1931-6) continued as The Fairy Chess Review (1936-51).

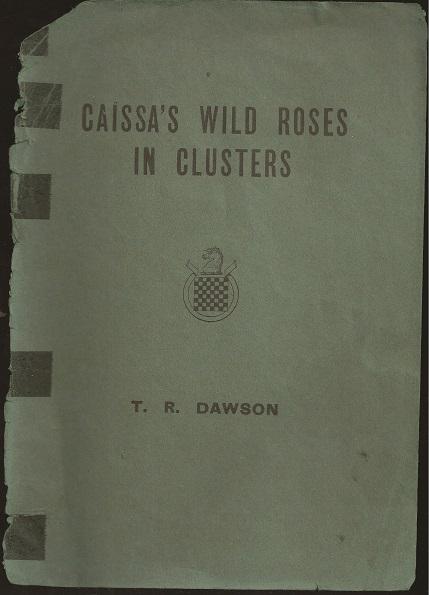

Besides conducting columns in several newspapers and periodicals, one of them daily and one in the Braille Chess Magazine, Dawson edited the problem section of the British Chess Magazine from 1931 to 1951; he devised and published in its pages (1947-50) a systematic terminology for problem themes in the hope that it would supplant the extensive jargon then and now in use, Dawson wrote five hooks on fairy problems: Caissa’s Wild Roses (1935); C. M. Fox, His Problems (1936); Caissa’s Wild Roses in Clusters (1937); Ultimate Themes (1938); and Caissa’s Fairy Tales (1947).

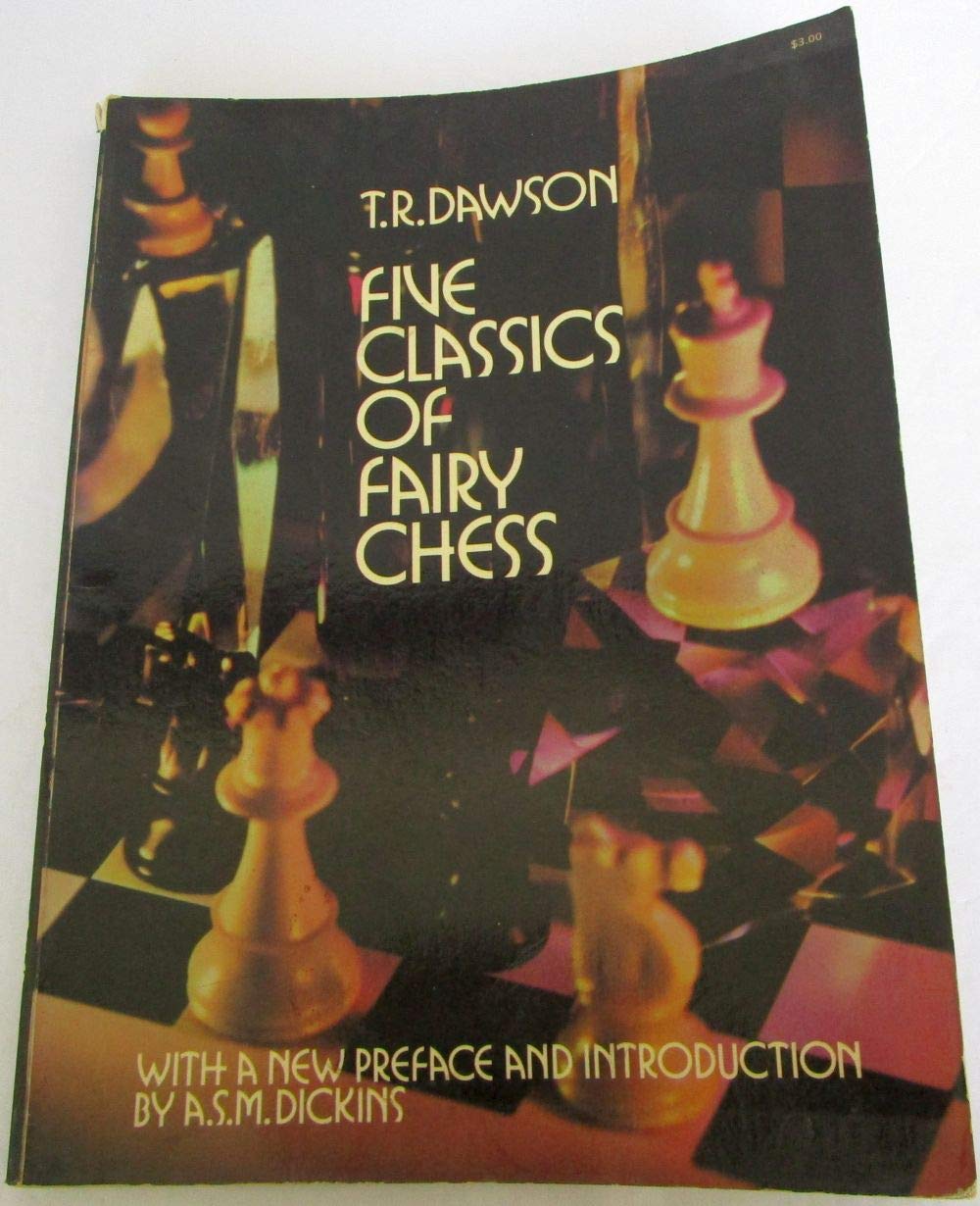

Charles Masson Fox (1866-1935) was a patron whose generosity made possible the publication of four of these books and the two fairy problem magazines founded by Dawson. Ultimate Themes deals with tasks, another of Dawson’s favourite subjects. In 1973 all five books were republished in one volume. Five Classics of Fairy Chess.

Dawson found it difficult to understand the problemist’s idea of beauty because it is not susceptible to precise definition. The artist talks of “quiet” moves, oblivious that they are White’s most pulverizing attacks! This aesthetic folly, reverence, response thrill to vain-glorious bombast runs throughout chess.(See Bohemian for a problem showing 16 model mates, a task Dawson claimed as a record but a setting Bohemian composers would reject.) His genius did not set him apart from his fellows; he could find time for casual visitors and would explain his ideas to a tyro with patience, modesty, and kindness. Although he won many tourney prizes much of his work was designed to encourage others, to enlarge the small band of fairy problem devotees, He composed less for fame than to amuse himself, confessing to another composer ‘We do these things for ourselves alone.’

A chemistry graduate, Dawson took a post in the rubber industry in 1922 and rose to be head of the Intelligence Division of the British Rubber Manufacturer for which he founded, catalogued, and maintained a technical library. Unwell for the last year of his life, he died from a stroke. K. Fabel and C. E. Kemp, Schach ohne Grenzen or Chess unlimited (1969) is a survey, written in German and English, of Dawson’s contribution to the art of fairy problems.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (Robert Hale 1970 & 1976), Anne Sunnucks :

“British problemist. Born on 28th November 1889. Died on 16th December 1951. Universally known as TRD., the great master of Fairy problems. His wealth of invention held the chess world enthralled. His output comprised about 6,400 problems and 150 studies.

Dawson was a nephew of the late James Rayner, himself a noted chess problemist . From as early as about 1910, TRD had conducted the ‘Chess Endings‘ section in the Chess Amateur, and its Fairy section from 1919. He worked with BG Laws from Mark 1930 conducting the problem pages of the British Chess Magazine, and following Laws’ death he assumed complete charge of the section from October 1931 to February 1951 when ill health forced him to relinquish the work.

The Problemist Fairy Chess Supplement subsequently renamed The Fairy Chess Review was started by TRD in August 1930. TRD was concerned in a number of other chess publications ; chess for the Blind, several books of the AC White Christmas series, BCPS Honours 1926-29, and the CM Fox series.

He was largely instrumental in the publication of the first issue of The Problemist on 1st January 1926, and was editor until May 1931. He was President of The British Chess Problem Society from September 1931 to 1943.

Apart from chess, Thomas Dawson, MSc, FRIC, FIRI was an international authority on rubber, and was responsible for the creation of the world-famous rubber library at Croydon, as well as its ‘Dawson’ system of rubber literature documentation. A Guide to Fairy Chess and The Problemist March 1952 detail the remarkable life-time accomplishments of TRD.”

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977), Harry Golombek OBE, John Rice writes:

“British problemist, output over 6,000, 5,000+ being fairies . Dawson is remembered especially for his enormous contribution to fairy chess, of which he was the world’s leading exponent. Not only did he invent new pieces (e.g. Grasshopper, Nightrider) and new forms (e.g. Serieshelpmate), he also popularised fairy ideas with unparalleled enthusiasm through his writing and editing.

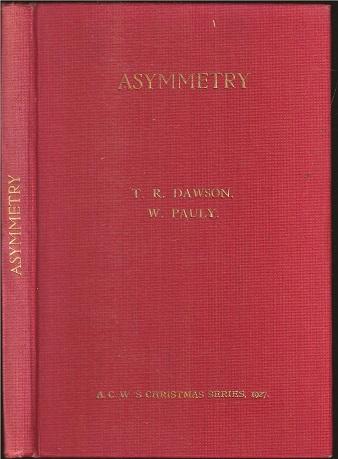

Books include Caissa’s Wild Roses (1935), Caissa’s Wild Roses in Clusters (1937), Ultimate Themes (1938), and Caissa’s Fairy Tales (1947); and in collaboration Retrograde Analysis (1915) and Asymmetry (1928).

Editor of The Problemist (1922-31), fairy secretary of Chess Amateur (1919-30, Fairy Chess Review (previously Problemist Fairy Supplement) (1930-51) and problem pages of the British Chess Magazine (1931-51). Of these, the Fairy Chess Review was probably his greatest achievement.

President of British Chess Problem Society 1931-43.”

When TRD stepped down as Endings editor of British Chess Magazine in December 1947 he wrote this:

“With this page I reluctantly terminate on health grounds some forty years of work in the Endings field, and my contributions to this corner of the “British Chess Magazine”. To the many readers of these pages, a Merry Christmas and steadily improving years.”

He handed over his column to Richard Guy.

From British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXI (71, 1951), Number 3 (March) pp. 78-80 we have notice of the retirement of TRD written by Brian Reilly:

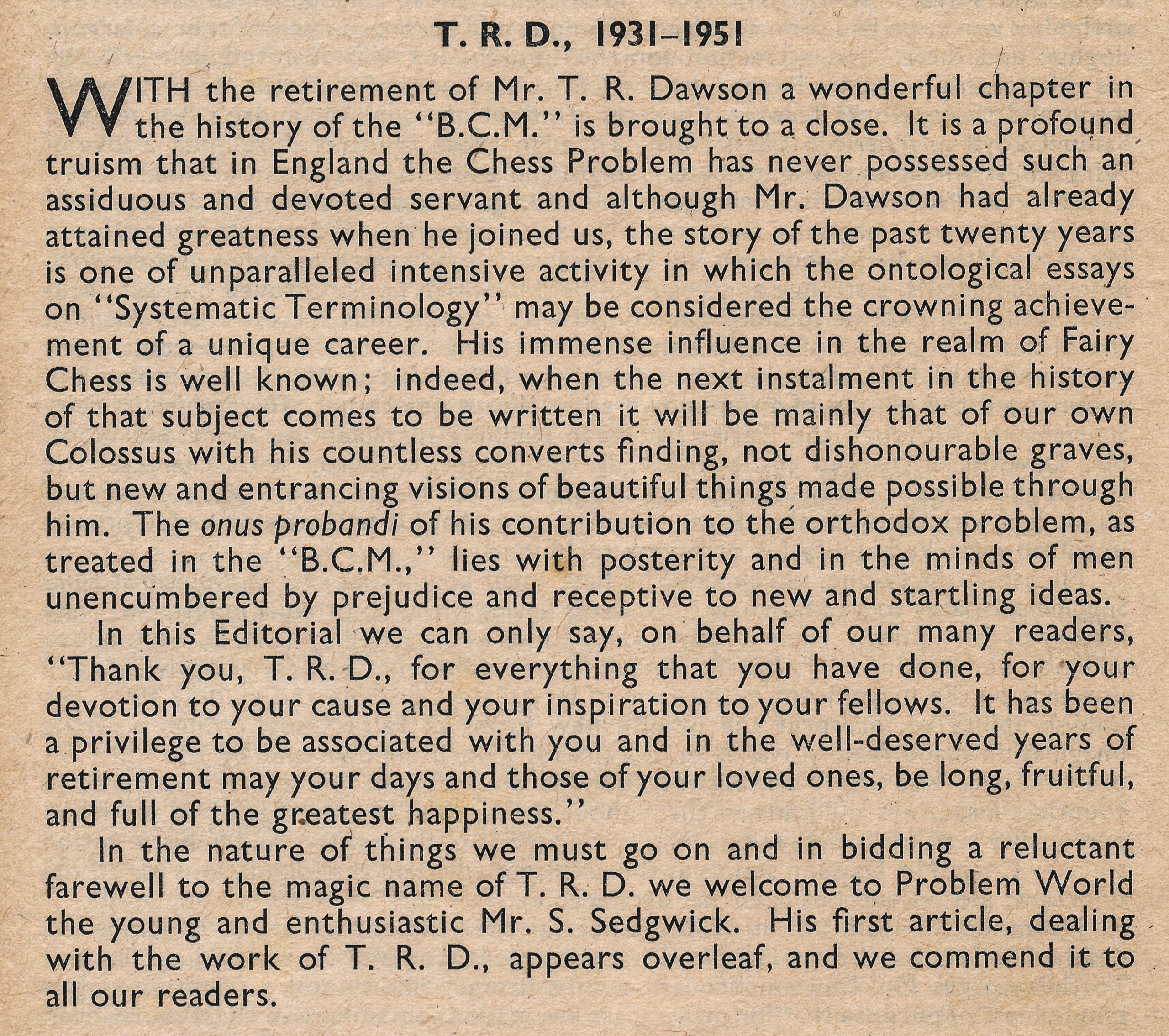

WITH the retirement of Mr. T. R. Dawson a wonderful chapter in the history of the “B.C.M.” is brought to a close. It is a profound truism that in England the Chess Problem has never possessed such an assiduous and devoted servant and although Mr. Dawson had already attained greatness when he joined us, the story of the Past twenty years is one of unparalleled intensive activity in which the ontological essays on “Systematic Terminology” may be considered the crowning

achievement of a unique career.

His immense influence in the realm of Fairy Chess is well known; indeed, when the next instalment in the history

of the subject comes to be written it will be mainly that of our own Colossus with his countless converts finding, not dishonourable graves, but new and entrancing visions of beautiful things made possible through him. The onus probandi of his contribution to the orthodox problem, as treated in the “‘B.C.M.,” lies with posterity and in the minds of men unencumbered by prejudice and receptive to new and startling ideas.

In this Editorial we can only say, on behalf of our many readers,

“Thank you, T. R. D., for everything that you have done: for your devotion to your cause and your inspiration to your fellows. It has been a privilege to be associated with you and in the well-deserved years of retirement may your days and those of your loved ones, be long, fruitful, and full of the greatest happiness.”

In the nature of things we must go on and in bidding. a reluctant farewell to the magic name of T. R. D. we welcome to Problem World the young and and enthusiastic Mr. S. Sedgwick. His first article, dealing with the work of T. R. D., appears overleaf, and we commend it to all our readers.

Here is that editorial as it originally appeared:

Following that we have this appreciation from the incoming Problem Editor, Stanley Sedgwick of 337 Strone Road, Manor Park, London E12:

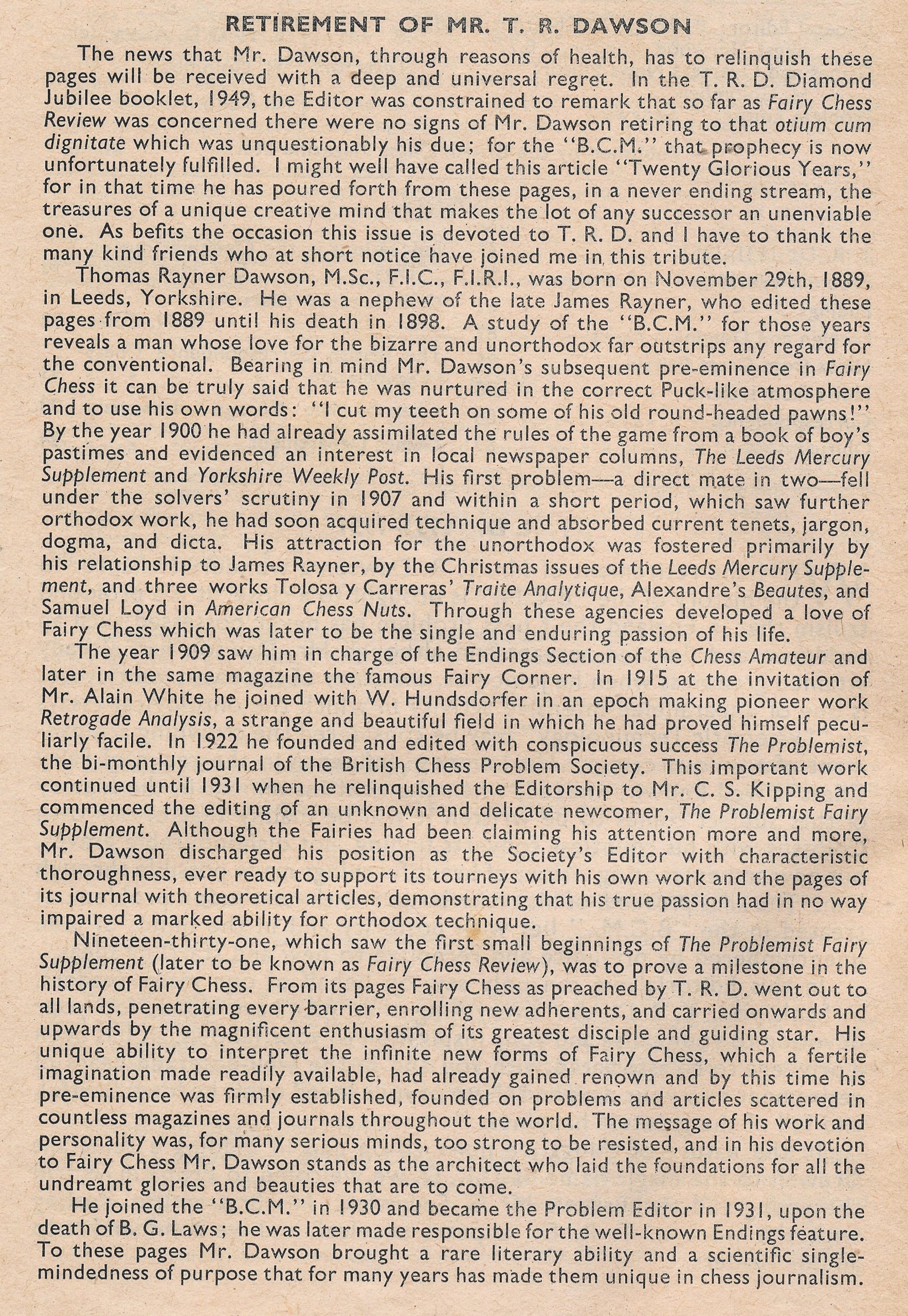

RETIREMENT OF MR. T. R. DAWSON

The news that Mr. Dawson, through reasons of health, has to relinquish these pages will be received with a deep and universal regret.

In the T. R. D. Diamond Jubilee booklet, 1949, the Editor was constrained to remark that so far as Fairy Chess Review was concerned there were no signs of Mr. Dawson retiring to that otium cum dignitate which was unquestionably his due; for the “B.C.M.” that prophecy is now unfortunately fulfilled. I might well have called this article “Twenty Glorious Years,” for in that time he has poured forth from these pages, in a never ending stream, the

treasures of a unique creative mind that makes the lot of any successor in unenviable one. As befits the occasion this issue is devoted to T. R. D. and I have to thank the many kind friends who at short notice have joined me in this tribute.

Thomas Rayner Dawson, M.Sc., F.I.C., F.I.R.I.. was born on November 29th, 1889, in Leeds, Yorkshire. He was a nephew of the late James Rayner, who edited these pages from 1889 until his death in 1898. A study of the “B.C.M.” for those years reveals a man whose love for the bizarre and unorthodox far outstrips any regard for the conventional. Bearing in mind Mr. Dawson’s subsequent pre-eminence in Fairy Chess it can be truly said that he was nurtured in the correct Puck-like atmosphere and to use his own words: “l cut my teeth on some of his old round-headed pawns!”

By the year 1900 he had already assimilated the rules of the game from a book of boy’s pastimes and evidenced an interest, in local newspaper columns, The Leeds Mercury Supplement and Yorkshire Weekly Post. His first problem – a direct mate in two – fell under the solvers’ scrutiny in 1907 and within a short period, which saw further orthodox work, he had soon acquired technique and absorbed current tenets, jargon, dogma, and dicta. – His attraction for the unorthodox was fostered primarily by his relationship to James Rayner, by the Christmas issues of the Leeds Mercury Supplement, and three works Tolosa y Carreras’ Traite Analytique, Alexandre’s Beautes, and Samuel Loyd in American Chess Nuts.

Through these agencies developed a love of Fairy Chess which was later to be the single and enduring passion of his life.

The year 1909 saw him in charge of the Endings Section of the Chess Amateur and later in the same magazine the famous Fairy Corner. In l915 at the invitation of Mr. Alain White he joined with W. Hundsdorfer in an epoch making pioneer work Retrograde Analysis, a strange and beautiful field in which he had proved himself peculiarly facile. In 1922 he founded and edited with conspicuous success The Problemist, the bi-monthly journal of the British Chess Problem Society.

This important work continued until 1931 when he relinquished the Editorship to Mr. C. S. Kipping and commenced the editing of an unknown and delicate newcomer, The Problemist Fairy Supplement. Although the Fairies had been claiming his attention more and more, Mr. Dawson discharged his position as the Society’s Editor with characteristic thoroughness, ever ready to support its tourneys with his own work and the pages of its journal with theoretical articles, demonstrating that his true passion had in no way impaired a marked ability for orthodox technique.

Nineteen-thirty-one, which saw the first small beginnings of The Problemist Fairy Supplement (later to be known as Fairy Chess Review), was to prove a milestone in the history of Fairy Chess. From its pages Fairy Chess as preached by T. R. D. went out to all lands, Penetrating every barrier, enrolling new adherents, and carried onwards and

upwards by the magnificent enthusiasm of his greatest disciple and guiding star.

His unique ability to interpret the infinite new forms of Fairy Chess, which a fertile imagination made readily available, had already gained renown and by this time his pre-eminence was firmly established, founded on problems and articles scattered in countless magazines and journals throughout the world. The message of his work and personality was, for many serious minds, too strong to be resisted, and in his devotion to Fairy Chess Mr. Dawson stands as the architect who laid the foundations for all the undreamt glories and beauties that are to come.

He joined the “8.C.M.” in 1930 and became the Problem Editor in 1931, upon the death of B. G. Laws; he was later made responsible for the well-known Endings feature. To these pages Mr. Dawson brought a rare literary ability and a scientific single-mindedness of purpose that for many years has made him unique in chess journalism.

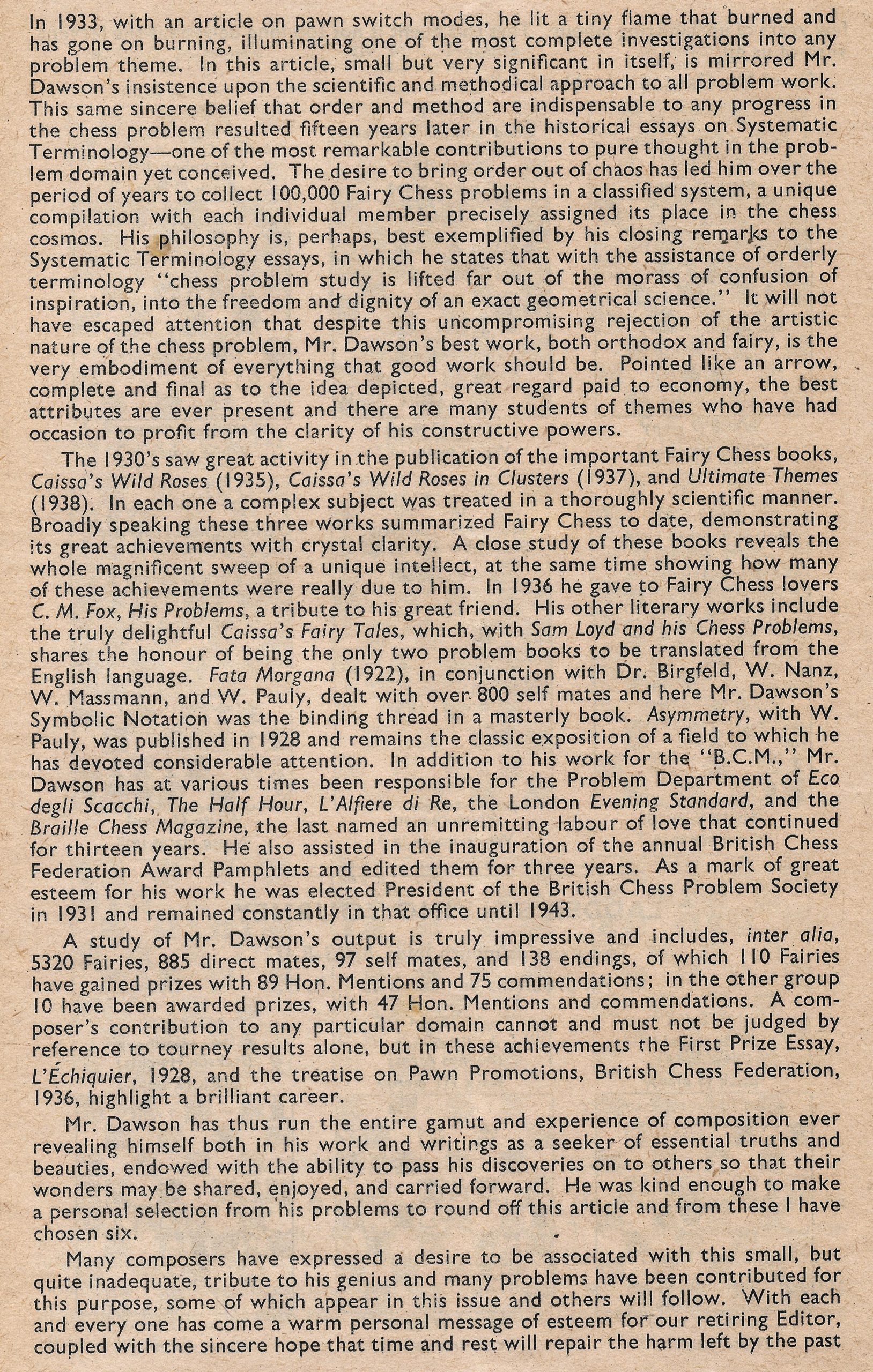

In 1933, with an article on pawn switch modes, he lit a tiny flame that burned and has gone on burning, illuminating one of the most complete investigations into any problem theme. In this article, small but very significant in itself, is mirrored Mr. Dawson’s insistence upon the scientific and methodical approach to all problem work.

The same sincere belief that order and method are indispensable to any progress in the chess problem resulted fifteen years later in the historical essays on Systematic Terminology – one of the most remarkable contributions to pure thought on the problem domain yet conceived. The desire to bring order out of chaos has led him over the period of years to collect 100,000 Fairy Chess problems in a classified. system, a unique compilation with each individual member precisely assigned its place in the chess cosmos. His philosophy is, perhaps, best exemplified by his closing remarks to the Systematic Terminology essays, in which he states that with the assistance of orderly terminology “chess problem study is lifted far out of the morass of confusion of inspiration, into the freedom and dignity of an exact geometrical science.” It will not

have escaped attention that despite this uncompromising rejection of the artistic nature of the chess problem, Mr. Dawson’s best work, both orthodox and fairy, is the very embodiment of everything that good work should be. Pointed like an arrow,

complete and final as to the idea depicted, great regard paid to economy, the best attributes are ever present and there are many students of themes who have had occasion to profit from the clarity of his constructive powers.

The 1930’s saw great activity in the publication of the important Fairy Chess books, Caissa’s Wild Roses (1935), Caissa’s Wild Roses in Clusters (1937), and Ultimate Themes (1938). In each one a complex subject was treated in a thoroughly scientific manner. Broadly speaking these three works summarized Fairy Chess to date, demonstrating

its great achievements with crystal clarity. A close study of these books reveals the whole magnificent sweep of a unique intellect, at the same time showing how many of these achievements were really due to him. ln 1936 he gave to Fairy Chess lovers C. M. Fox, His Problems, a tribute to his great friend. His other literary works include the truly delightful Caissa’s Fairy Tales, which, with Sam Loyd and his Chess Problems shares the honour of being the only two problem books to be translated from the English language. Fata Morgana (1922), in conjunction with Dr. Birgfeld, W. Nanz,W. Massmann and W. Pauly, dealt with over 800 self mates and here Mr. Dawson’s Symbolic Notation was the binding thread in a masterly book. Asymmetry, with W. Pauly was published in 1928 and remains the classic exposition of afield to which he has devoted considerable attention.

In addition to his work for the “B.C.M.,” Mr. Dawson has at various times been responsible for the Problem Department of Eco degli Scacchi, The Half Hour, L’Alfiere di Re, the London Evening Standard, and the

Braille Chess Magazine, the last named an unremitting labour of love that continued for thirteen years. He also assisted in the inauguration of the annual British Chess Federation Award Pamphlets and edited them for three years. As a mark of great respect for his work he was elected President of the British Chess Problem Society in 1931 and remained constantly in that office until 1943.

A study of Mr. Dawson’s output is truly impressive and includes, inter alia, 5302 Fairies, 885 direct mates, 97 self mates and 138 endings, of which 110 Fairies have gained prizes with 89 Hon. Mentions and 75 commendations; in the other group 10 have been awarded prizes, with 47 Hon. Mentions and commendations. A composer’s contribution to any particular domain cannot and must not be judged by reference to tourney results alone, but in these achievements the First Prize Essay, L’Echiquier, 1928, and the treatise on Pawn Promotions, British Chess Federation, 1936, highlight a brilliant career.

Mr. Dawson has thus run the entire gamut and experience of composition ever revealing himself both in his work and writings as a seeker of essential truths and beauties, endowed with the ability to pass his discoveries on to others so that their wonders may be shared, enjoyed, and carried forward. He was kind enough to make a personal selection from his problems to round off this article and from these I have chosen six.

Many composers have expressed a desire to be associated with this small, but quite inadequate, tribute to his genius and many problems have been contributed for this purpose, some of which appear in this issue and others will follow. With each

and every one has come a warm personal message of esteem for our retiring Editor, coupled with the sincere hope that time and rest will repair the harm left by the past years of unremitting labour. That this event is not too long delayed is the fervent wish of us all.

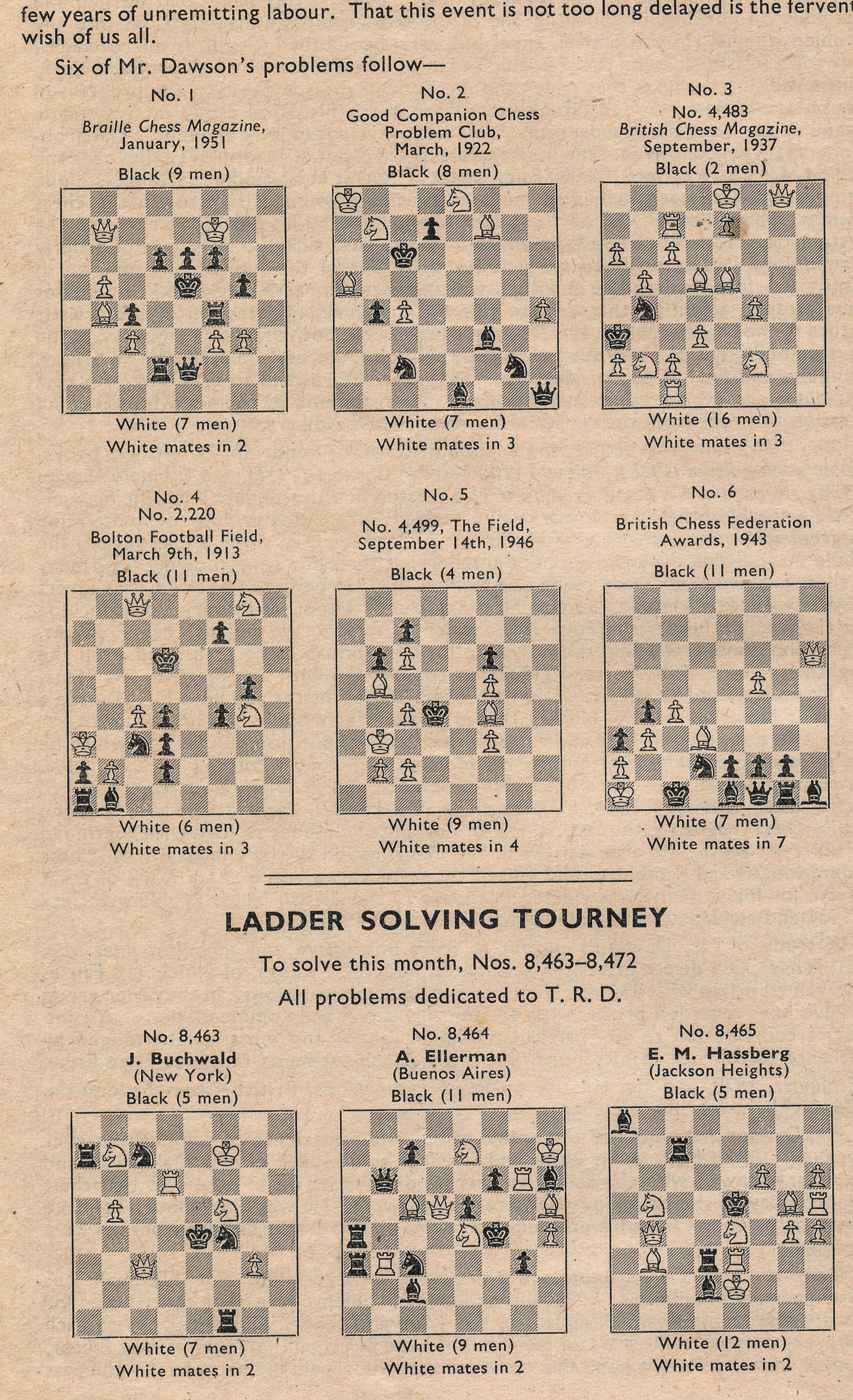

Six of Mr. Dawson’s problems follow –

No. 1

British Chess Magazine, January, 1951

White mates in 2

No. 2

Good Companion Chess Problem Club, March, 1922

White mates in 3

No. 3

British Chess Magazine, September, 1937

White mates in 3

No. 4

Bolton Football Field, March 9th, 1913

White mates in 3

No. 5

The Field, September 14th, 1946

White mates in 4

No. 6

British Chess Federation Awards, 1943

White mates in 7

and here follows the original article:

Unfortunately TRD was to pass away not much more than a year after the retirement notice and in British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXII (72, 1952), Number 4 (April) pp. 107 – 108 we have this obituary also from Stanley Sedgwick :

The same obituary contains the following appreciation by Gerald Abrahams :

According to Edward Winter in Chess Explorations (Cadogan Chess, 1996) page 106, Chess Note 457, :

“George Jellis suspects that a chess man has been named after a street:

Just south of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London is a private gated road called Nightrider Street which, I believe belongs to the Post Office and presumably derives its name from the night mail coaches of earlier days. It is only a short walk from the St. Bride’s Institute, where the British Chess Problem Society has held its meetings since its foundation in 1918. Among the founder members was TR Dawson, who published his first Nightrider problem in 1925.

From Wikipedia :

“Thomas Rayner Dawson (28 November 1889 – 16 December 1951) was an English chess problemist and is acknowledged as “the father of Fairy Chess”.[1] He invented many fairy pieces and new conditions. He introduced the popular fairy pieces grasshopper, nightrider, and many other fairy chess ideas.

Dawson published his first problem, a two-mover, in 1907. His chess problem compositions include 5,320 fairies, 885 directmates, 97 selfmates, and 138 endings. 120 of his problems have been awarded prizes and 211 honourably mentioned or otherwise commended. He cooperated in chess composition with Charles Masson Fox.

Dawson was founder-editor (1922–1931) of The Problemist, the journal of the British Chess Problem Society. He subsequently produced The Fairy Chess Review (1930–1951), which began as The Problemist Fairy Chess Supplement. At the same time he edited the problem pages of The British Chess Magazine (1931–1951).

Publications

Caissa’s Playthings a series of articles in Cheltenham Examiner (1913)

Retrograde Analysis, with Wolfgang Hundsdorfer (1915)

Fata Morgana, with Birgfeld, Nanz, Massmann, Pauly (1922)

Asymmetry, with W. Pauly (1928)

Seventy Five Retros (1928)

Caissa’s Wild Roses (1935)

C. M. Fox, His Problems (1936)

Caissa’s Wild Roses in Clusters (1937)

Ultimate Themes (1938)

Caissa’s Fairy Tales (1947)

The last five titles were collected as Five Classics of Fairy Chess, Dover Publications (1973), ISBN 978-0-486-22910-2.”

We send birthday wishes to IM Ian Lloyd Thomas born this day (December 14th) in 1967.

Ian was a member of London Central YMCA (CentYMCA).

Ian played top board for Watford Grammar School in the (Sunday Times) National Schools Competition.

His earliest games in MegaBase 2020 are from various Lloyds Bank Opens from 1983 onwards. He played in a few British Championships and then the Washington Open in 1990. His next appearance was in the Himalayan Open in 2010.

According to ChessBase, Ian reached his highest FIDE rating of 2365 in July 1991 aged 24 although we believe he achieved 2400 at a Hastings and then withdrew.

Where are you now Ian?

We think he is residing in the USA.

A Startling Chess Opening Repertoire : Chris Baker and Graham Burgess

FIDE Master Graham Burgess needs no introduction to readers of English language chess books ! Minnesota, USA based, Graham has authored more than twenty five books and edited at least 250 and is editorial director of Gambit Publications Ltd. In 1994 Graham set a world record for marathon blitz playing and has been champion of the Danish region of Funen !

We previously reviewed Chess Opening Traps for Kids also by Graham Burgess.

This new book is an extensive rewrite and update of the original (1998) edition by IM Chris Baker.

Baker and Burgess have provided a complete repertoire for the White player based around 1.e4 and the Max Lange Attack with suggested lines for White against each and every reasonable reply from Black. Logically, the content is organised based on the popularity of Black’s first move and therefore the order is

and for each Black defence the authors have selected sharp and challenging lines for White that will definitely give Black something to think about. We have sampled some of these lines and confirm that they are variations that Black needs to tread very carefully in to stay on the board. They are all sound and not based on “coffee house gambits” or cheap traps.

Who is the intended audience of this book ? Well, clearly anyone who currently plays 1.e4 or is contemplating adding 1. e4 to their repertoire. Also, anyone who faces 1.e4 (and that is everyone who plays chess!) should be aware of of what might land on their board when they are least expecting it. As Robert Baden Powell would advise : “Be prepared !”

Unfortunately, We do not possess a copy of the original 1998 edition and we were curious as to the extent of the changes. The Introduction states :

“For this new edition, I have sought to retain the spirit and aims of the original book, while bringing the content fully up-to-date, making a repertoire that will work well in 2019 and for years to come.

In a sense it is basically a new book: wherever anything needed correcting, updating, replacing or adding, I have done so. Where material is unaltered, this is because it passed verification and nothing needed to be added. … the overall recommendations were not changed unless this was necessary. Some lines covered in this book basically didn’t exist in 1998, so I needed to decide what line against them was most in keeping with the rest of the repertoire.”

We followed up on the above and contacted the author (GB) receiving a very helpful reply as follows :

Something like 70% of the content is either new or modified so much as to be basically new. Examples of lines that essentially didn’t exist in 1998 include “Tiger’s Modern” and the 3…Qd6 Scandinavian. Lines where the old recommendation has been replaced (since it was fundamentally flawed in some way) include the Modern Philidor and the Two Knights French with 3…d4 (I briefly explain the switch from 5 c3 to 5 b4).

The whole Three Knights/Four Knights section in Chapter 10 is new, both to fill the repertoire hole and to provide an alternative vs the Petroff to those who don’t like the Cochrane.

But, almost every part of the book features fundamental changes. Little remains of the original Part 3 of the Sicilian chapter (other than the basic theme of a fianchetto set-up), for instance.

My aim was to be faithful to the aims of the original book, but only to the specifics where they still work, or where there isn’t a new possibility that fits better with the repertoire.

and furthermore :

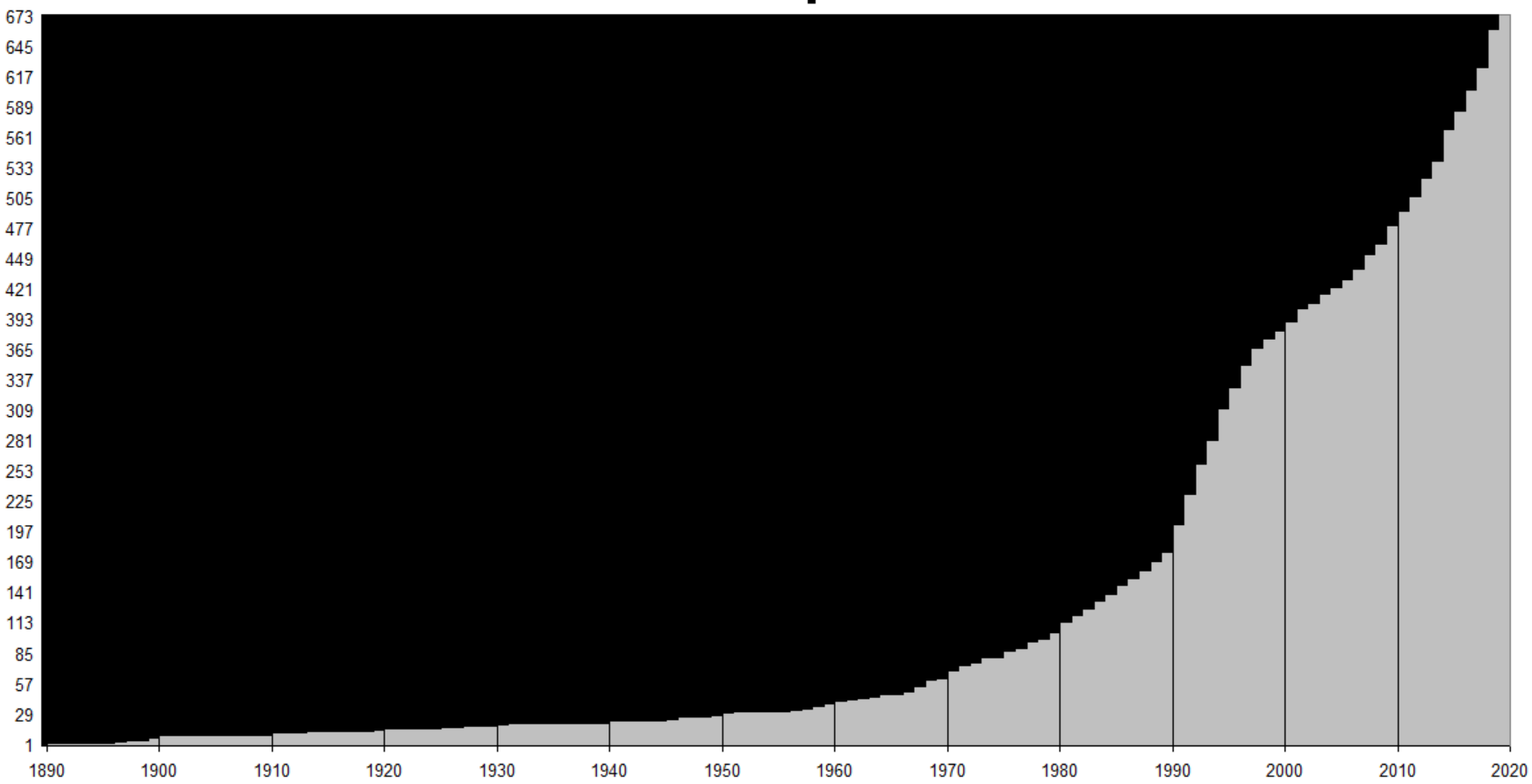

I have attached a graph showing the years the game references come from. The number for each year shows the cumulative total up to that year. Though this doesn’t really tell the full story, as I cited game references in a very sparing way, only using them when there seemed a real purpose in doing so.

and here is that graphic (courtesy of Graham) :

Clearly we are not going to reveal all of the suggestions here as that really would be a spoiler. Suffice to say that players of the Black lines would be wise to be aware of B&Bs suggestions ! We would recommend that any of the lines are tried out in off-hand games and on-line before important games and some of the more critical ones will need a degree of memorization to a fair few moves deep.

In the BCN office we have a Caro-Kann expert who confirmed that B&Bs suggestions for White are most definitely on the cutting edge and were checked with Stockfish 10. Indeed a team mate tried the suggestion for White in a league match and the opponent (a Caro-Kann player of more than forty years) had a catastrophic loss on his hands in short order.

As a taster here is a suggested line from the book that is full of pitfalls for Black :

We consulted an experienced (and successful) player of the Elephant Gambit* and was told that he had never faced White’s fifth move suggestion in more than twenty years and that it was an excellent suggestion worthy of respect. *Some might know this as the Queen’s Pawn Counter Gambit (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d5!?)

In summary, this second edition is a substantial update and improvement of a first edition well received and we recommend it heartily to anyone who wants to sharpen and refresh their 1.e4 repertoire and anyone who faces 1.e4. You will not be disappointed and you might be ready for someone’s preparation and shock tactics !

John Upham, Cove, Hampshire, December 13th 2019

Book Details :

Official web site of Gambit Publications Ltd.

Here is an excellent article from the Yorkshire Chess History site

Best wishes to GM Simon Williams on his fortieth birthday, this day (November 30th) in 1979.

Simon was Southern Counties (SCCU) champion in the 2001-02 (shared with Simon Knott) and the 2006-07 season.

His Wikipedia entry is here

The Gijon International Chess Tournaments, 1944-1965 : Pedro Méndez Castedo & Luis Méndez Castedo

Pedro Méndez Castedo & Luis Méndez Castedo

Pedro Mendez Castedo is an amateur chess player, an elementary educational guidance counselor a member of the Asturias Chess History Commission, a bibliophile and a researcher of the history of Spanish and Asturian chess. He lives in San Martin del Rey Aurelio, Spain. Luis Mendez Castedo is an amateur chess player, a full teacher at a state school, a member of the Asturias Chess History Commission, a bibliophile and an investigator of the history of Spanish chess. He lives in Gijon, Spain.

When I mention Gijón, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? Mustard? No, that’s Dijon. Dijon’s in France, but Gijón’s on the north coast of Spain, on the Bay of Biscay.

Small international chess tournaments were held there between 1944 and 1951, then between 1954 and 1956, and, finally, in 1965. These were all play all events, with between 8 and 12 players: a mixture of visiting masters and local stars. A bit like Hastings, you might think, but these tournaments usually took place in July, not in the middle of winter.

The strength of the tournaments varied, but some famous names took part. Alekhine played in the first two events and Euwe in 1951. A young Larsen played in 1956, while other prominent masters such as Rossolimo, Darga, Donner, Prins, Pomar and O’Kelly also took part. The local player Antonio Rico played in every event, with fluctuating fortunes: winning in 1945 ahead of Alekhine and 1948, but also finishing last on several occasions. English interests were represented on three occasions by Mr CHESS, BH Wood.

A nice touch is the Foreword, written by Gene Salomon, a Gijón native who played in the 1947 event before emigrating first to Cuba and then to the United States.

The main part of the book comprises a chapter on each tournament. We get a crosstable and round by round individual scores (it would have been better if these didn’t spill over the page: you might also think that progressive scores would be more useful). We then have, another nice touch, a summary of what was happening in the world at large, and in the chess world, that year. Then we have a games selection, some with light annotations: words rather than variations, giving the impression that little if any use was made of engines.

The book concludes with a chapter on ‘Special Personages’: Félix Heras, the tournament organizer, and, perhaps to entice British readers, BH Wood. Appendices provide a table of tournament participation and biographical summaries of the players.

Returning to the main body of the book, let’s take the 1950 tournament as a not entirely random example. A year in which I have a particular interest.

We learn a little about the football World Cup, the Korean War and a Spanish radio programme, the first Candidates Tournament and the Dubrovnik chess olympiad.

The big news from Gijón was the participation of the French player Chantal Chaudé de Silans, the only female to take part in these events, and rather unfairly deprived of her acute accent here. She scored a respectable 3½ points, beating Prins and Grob (yes, the 1. g4 chap).

Rossolimo won the event with 8½/11, just ahead of Dunkelblum and Pomar on 8. Prins and Torán, playing in his home city, finished on 7 points.

This game, between Arturo Pomar and Henri Grob, won the first brilliancy prize.

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 g6 3. Nc3 d5 4. cxd5 Nxd5 5. g3 Bg7 6. Bg2 c6 7. e3 h5 8. Nge2 h4 9. Qb3 Nxc3 10. bxc3 Nd7 11. a4 Nb6 12. a5

12… Nd7 13. a6 Qc7 14. Qc4 Nb6 15. Qc5 Rh5 16. Qa3 bxa6 17. Nf4 Rh8 18. Qc5 Bb7 19. Ba3 e5 20. Nd3 exd4 21. cxd4 Rh5 22. Ne5 O-O-O 23. g4 Nd7 24. Qc2 Rxe5 25. dxe5 Nxe5 26. Rb1 h3 27. Be4 Nxg4 28. Ke2 a5 29. Rxb7 Kxb7 30. Rb1+ Kc8 31. Bxc6 Ne5 32. Bb7+ Kb8 33. Ba6+ Qb6 34. Bd6+ Ka8 35. Rxb6 1:0

The annotations – by result rather than analysis – neither convince nor stand up to computer scrutiny. We’re told at the start of the game that ‘Pomar takes the initiative from Black’s error in the opening and does not relinquish it until the final victory’, but the annotations refute this claim. After criticizing several of Grob’s moves but none of Pomar’s, we’re told, correctly, that Black could have gained an advantage by playing 25… Qa5+. However, Grob’s choice was second best, not a ‘serious mistake’: Stockfish 10 tells me 26… a5 was still better for Black, and 27… a5 (in both cases with the idea of Ba6) was equal, though I guess those moves might not be easy to find without assistance. It was his 27th move, and perhaps also his 26th, which deserved the question mark.

This game was played in the last round of the tournament, on 26 July 1950. Two days later a boy would be born who would learn chess, develop an interest in the game’s history and literature, and be asked to review this book. What is his verdict?

An enjoyable read, a nice book, but not a great book. If you collect McFarland books you’ll want it. If you have a particular passion for Spanish chess history, you’ll want it. Otherwise, although the book is not without interest, it’s probably an optional extra.

The tournaments, apart perhaps from Alekhine’s participation in the first two events, are not, in the overall scheme of things, especially significant. The games, by and large, aren’t that exciting. The annotations are, by today’s standards, not really adequate. The translation and presentation could have been improved.

Just another thought: we could do with a similarly structured book about the Hastings tournaments. There was one published some years ago, but a genuine chess historian could do much better.

Richard James, Twickenham 20 November 2019

Book Details :

Official web site of McFarland

Emanuel Lasker: A Reader: A Zeal to Understand : Taylor Kingston

Taylor Kingston

Taylor Kingston has been a chess enthusiast since his teens. He holds a Class A over-the-board USCF rating, and was a correspondence master in the 1980s, but his greatest love is the game’s history. His historical articles have appeared in Chess Life, New In Chess, Inside Chess, Kingpin, and the Chess Café website. He has edited numerous books, including the 21st-century edition of Lasker’s Manual of Chess, and translations from Spanish of The Life and Games of Carlos Torre, Zurich 1953: 15 Contenders for the World Championship, and Najdorf x Najdorf. He considers the Lasker Reader to be the most challenging and interesting project he has undertaken to date.

When I’m asked who my favourite chess player is, I always answer ‘Emanuel Lasker’.

Why? Partly because he was a player who didn’t really have a style. Like Magnus Carlsen, with whom he has sometimes been compared, he just played chess. But more because he was such an interesting personality. Unlike most champions (Euwe and Botvinnik were exceptions) he had a life outside chess, on several occasions taking long breaks from the game. And what a life it was: mathematician, philosopher, writer, playwright, bridge player, and, lest we forget, chess player.

Chess historians are finally taking notice of this fascinating man. In 2009 a massive volume about him was published in German, edited by Richard Forster and others. Last year the first of three volumes of a greatly expanded edition of this work appeared in English. If you have any interest at all in chess history you should certainly possess this book, and, like me, you’ll be eagerly looking forward to volumes 2 and 3.

What we have here might best be seen as a companion to this work, and, if you’re a Lasker fan or have any interest in chess history you’ll want this as well.

Taylor Kingston has compiled and edited a collection of Lasker’s own writings, not just on chess but covering every aspect of his multi-faceted personality.

We start with the London Chess Fortnightly, which Lasker published for a year between 1892 and 1893, annotating his own games as he was trying to establish himself as a contender for Steinitz’s world title. Here and throughout the book, the editor adds the occasional contribution from Stockfish 8.

Lasker and Steinitz met in 1894, with our hero becoming the second official world champion as a result of winning the match. Both players annotated some of the games for newspaper columns. In 1906 Lasker published this in his chess magazine, which we’ll come to later, but in this book they appear in the correct chronological place.

The Hastings 1895 tournament book (if you don’t have a copy I’d like to know why) was unusual in that all the games were annotated by one of the other participants. The six games Lasker annotated feature here.

Lasker’s first book, Common Sense in Chess, was published the following year. We have here an extract from Chapter 9, the End Game.

We then jump forward to 1904. The longest and, for chess players, perhaps the most interesting section of the book covers Lasker’s Chess Magazine, which was published in New York between November 1904 and January 1909. The games themselves give the reader an overview of chess during those years, with amateurs as well as masters being represented. Lasker’s annotations and, in some cases, game introductions, were often colourful in nature and tell us a lot about the man himself.

Burn-Forgacs (Ostend 1906), for instance, ‘begins like a summer breeze and ends like a winter’s gale’.

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Bg5 Nbd7 5. e3 c6 6. Nf3 Qa5 7. Nd2 Ne4 8. Ndxe4 dxe4 9. Bh4 e5 10. Be2 f5 11. O-O g6 12. c5

‘Here the red lantern flashes out; queen and bishop prepare to take the diagonal from b3 to e6 and f7, which are woefully weak, and the black king will be in grave peril.’

12… Bg7 13. Qb3 Nf8 14. Bc4 Qc7 15. d5 h6 16. d6 Qd7 17. Be7 Ne6 18. Nb5 cxb5 19. Bxb5 1-0

Another major chapter concerns the 1908 Lasker-Tarrasch world championship match. After some details of the background to the match (there was little love lost between the two players: Edward Lasker quoted Tarrasch as saying ‘the only words I will address to him are check and mate!). Taylor Kingston presents the games with annotations from Lasker’s Chess Magazine, Tarrasch’s book of the match and other contemporary sources, along with the usual computer interjections.

We then have a chapter on Lasker’s unsuccessful 1921 match against Capablanca, and another on his non-appearance at New York 1927. Lasker’s Manual of Chess was first published in German in 1926: here we have an excerpt in which he discusses the theory of Steinitz.

Lasker’s chess writings are completed by an article on Lasker and the Endgame by guest contributor Karsten Müller, and a short section on Lasker’s problems and endgame studies.

The last 75 pages of the book consider other aspects of Lasker’s life: his philsophy, his contributions to mathematics, and Lasca, a board game he invented.

Perhaps the most interesting section offers extracts from The Philosophy of the Unattainable, his most important philosophical work, published in 1919. As far as Taylor Kingston is aware, it has never been published in English.

Lasker’s last work, The Community of the Future, was published in 1940, five months before his death. Here, Lasker considers the problems faced by the world and proposes a ‘non-competitive community’ as his solution, with ‘self-hope co-operatives’ to deal with unemployment. Again, fascinating reading, and, you might think, his utopian ideas are still of some relevance today.

The book is a well-produced paperback. There are a few notation errors caused by translation from descriptive to algebraic, but this shouldn’t cause you too much bother. I hope I’ve convinced you that this book deserves a place on your shelves.

Richard James, Twickenham 20 November 2019

Book Details :

Official web site of Russell Enterprises