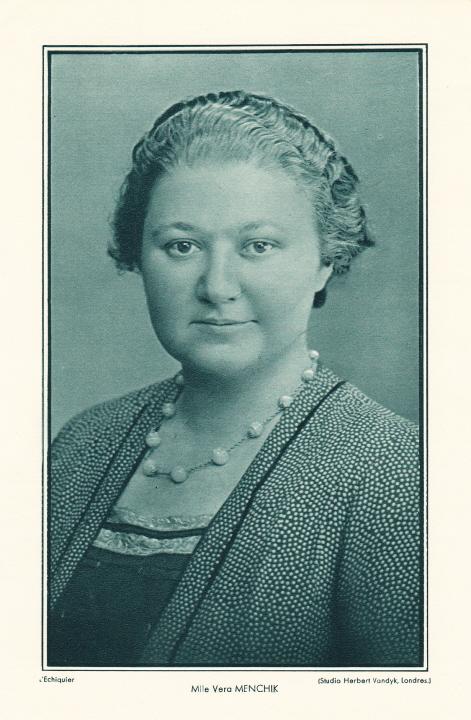

A Great Life with a Tragic Ending

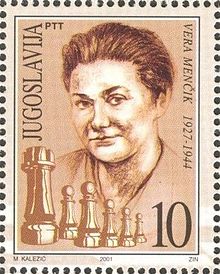

Few people know the story of Vera Menchik yet it deserves to be told. She was the first women’s world chess champion in 1927 and retained the title undefeated until her untimely death at the age of 38 in 1944 during a V1 flying bomb attack on London. She is more properly compared with the great male players of her era against whom she scored creditably. The absence of a full biography of Vera in English reflects the peculiar circumstances of her life and death.

Vera was, in modern terminology, a refugee and essentially a stateless person for much of her life. She was born in Moscow in 1906 during the period of the Russian Empire to an expatriate family who was forced to flee when she was 15 following the Russian Revolution having lost their livelihood. As they passed through Europe, her father and mother split up in his homeland Czechoslovakia which had been created out of the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian empire. She arrived in England and took up residence in the seaside town of Hastings. (The fact that Hastings had hosted the world’s longest series of annual chess tournaments since 1895 was a happy coincidence.) Vera never attained British nationality until near the end of her life even though she had been domiciled in England from 1921. She won the first-ever Women’s World Championships held in London in 1927 under a Russian flag; thereafter she nominally represented Czechoslovakia until finally she represented England in 1939 following her marriage to a senior official within the British Chess Federation.

Vera’s grandfather was Arthur Illingworth, a wealthy trader from Lancashire who had set up business in Moscow where his Anglo-Russian daughter Olga married František Menčik. He was a successful estate manager. Vera learned chess from her father and performed well at school. Her younger sister Olga was also a good chess player and the sisters remained close throughout their lives.

Vera was a woman in a man’s world – she had to struggle harder to achieve the kind of recognition which was accorded to men. She appeared like a comet in the sky and it would be many years until other women were able to reach her level. At her first major international tournament at Karlsbad in 1929, she was the only female participant in a tournament of 22 great players. Even as women’s world champion, some of the male players objected to her participation. The Viennese master Albert Becker joked that anybody who lost to her should belong to the Vera Menchik Club. By an irony of history, he became its first member losing to her in the third round. She beat many other grandmasters during her career including the Dutchman Max Euwe in 1930 and 1931 (both at Hastings) who was to become world champion in 1935.

Although she is often portrayed as being Russian or Czech or latterly British, she was a true cosmopolitan. She knew that life could be unstable in any country. She had lived through the Russian Revolution; one parent was left behind in Czechoslovakia; she had moved westwards across Europe and embraced different cultures and languages at formative stages of her life. It is no wonder that she learned also to speak Esperanto which was designated to be the world’s lingua franca before English achieved its dominance. As a leading chess player, she travelled back to Moscow and to Czechoslovakia several times as well as to South America for her final match to retain the women’s world champion title in 1939. She needed to be self-sufficient and was obtained roles as the games editor of a chess magazine as well as being appointed the manager of the National Chess Centre in Oxford Street which was destroyed during the Blitz in 1940.

She survived most of the war and now a widow moved in with her mother and sister to a house in south London. They took the precaution of going down to the cellar during bombing raids. Tragically the house received a direct hit from a flying bomb and the entire family was wiped out. Hardly any of her possessions remained save for one dented trophy. The records at the national chess centre were destroyed as were her personal effects including her chess memorabilia. At least there remains a record of the moves played in her games which serve as testimony to her remarkable career as not only the first women’s world chess champion but also a woman who broke boundaries wherever she went and demonstrated that a woman is capable of standing on her own feet professionally and leading a full and eventful life.

The Bomb Attack

BCN remembers that in the early morning of Tuesday, June 27th, 1944 (i.e. 77 years ago) Vera Menchik, her sister Olga, and their mother were killed in a V-1* flying bomb attack which destroyed their home at 47 Gauden Road in the Clapham area of South London.

We now know that the V1 in question landed at 00:20 hrs on the 27th and led to the death of a total of 11 people including the Menchik household. Here is a summary of recorded V1 and V2 landings in the Clapham, SW4 area.

(*The V-1 was an early cruise missile with a fairly crude guidance system.)

All three were cremated at the Streatham Park Crematorium on 4 July 1944. Vera was 38 years old.

Vera’s Parents and Sister

Vera Frantsevna Menchik (or Věra Menčíková) was born in Moscow on Friday, 16th February, 1906. Her father was František Menčik, was born in Bystrá nad Jizerou, Bohemia. František and Olga were married on June 23rd 1905 in Moscow and notice of this marriage appeared in British newspapers on July 22nd 1905. Vera’s sister was Olga Rubery (née Menchik) and she was born in Moscow in 1908. Olga Menchik married Clifford Glanville Rubery in 1938. Vera married Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson on October 19th 1937.

Her Maternal Roots

Our interest in unearthing her maternal English heritage / roots has led to the following:

Her mother was Olga (née Illingworth (1885 – 27 vi 1944). Olga’s parents were Arthur Wellington Illingworth and Marie Illingworth (née ?). Arthur was born in October 1852 in the district of Salford, Lancashire, his parents were George Illingworth (1827-1887) and Alice Whewell (1828-1910).

In the 1861 census Arthur is recorded as being of eight years of age and living in the Illingworth household.

In the 1871 census Arthur is recorded as being of eighteen years of age and living in the Illingworth household of nine persons at 5, Lancaster Road, Pendleton, Lancashire. Arthur’s occupation is listed as being a merchants apprentice. In fact, he was a stock and share broker.

Arthur died in Moscow on February 21st 1898. Probate was recorded in London on July 6th, 1900 as follows:

Illingworth Arthur Wellington of Moscow Russia merchant died 21st February 1898 Probate London 6th July to Walter Illingworth stock and share-broker Effects £4713 7s

£4713 7s in 1898 equates roughly to £626,600.00 in 2020 so it would appear that Arthur was considerably successful and almost certainly left money to Olga Illingworth.

What do we conclude from all of this? Quite simply that Vera’s maternal roots were from Salford in Lancashire.

BCM Announcement

The August 1944 British Chess Magazine (Volume LXIV, Number 8, page 173 onwards) contained this editorial from Julius du Mont:

“British Chess has suffered a grievous and irreparable loss in the death by enemy action of Mrs. R.H.S. Stevenson known through all the world where chess is played as Vera Menchik.

We give elsewhere (below : Ed.) an appreciation of this remarkable woman. Quite apart from her unique gifts as a chess-player-the world may never see her equal again among women players-she had many qualities which endeared her to all who knew her, the greatest among them being here great-hearted generosity.

We sympathise with our contemporary “CHESS” : Vera Menchik was for some years their games editor. Few columns have been conducted with equal skill and efficiency and none, we feel sure, with a greater sense of responsibility.

The news of this remarkable tragedy will be received by the chess world with sorrow and with abhorrence of the wanton and useless robot methods of a robot people.

One shudders at the heritage of hatred which will be theirs, but their greatest punishment will come with their own enlightenment.”

BCM Contemporary Obituary from EGR Cordingley

From page 178 of the same issue we have an obituary written by EGR Cordingley :

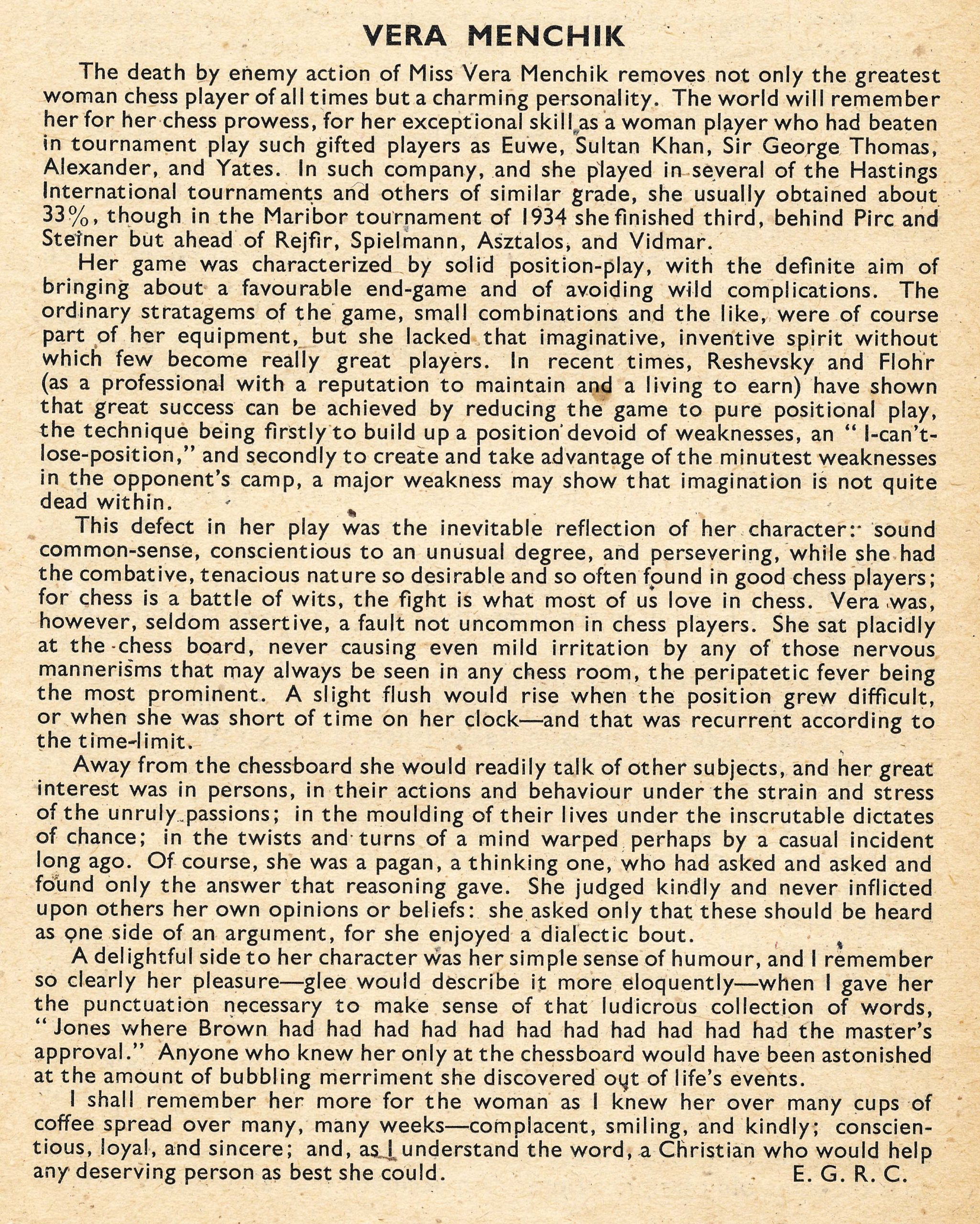

“The death by enemy action of Miss Vera Menchik removes not only the greatest woman chess player of all times but a charming personality.

The world will remember her for her chess prowess, for her exceptional skill as a woman player who had beaten in tournament play such gifted players as Euwe, Sultan Khan, Sir George Thomas, Alexander and Yates. In such company, and she played in several of the Hastings International tournaments and other of similar grade, she usually obtained about 33%, though in the Maribor tournament of 1934 she finished third, behind Pirc and Steiner but ahead of Rejfir, Spielmann, Asztalos and Vidmar.

Her game was characterised by solid position-play, with the definite aim of bringing about a favourable end-game and of avoiding wild complications. The ordinary stratagems of the game, small combinations and the like, were of course part of her equipment, but she lacked that imaginative, inventive spirit without which few become really great players.

In recent times, Reshesvky and Flohr (as a professional with a reputation to maintain and a living to earn) have shown that great success can be achieved by reducing the game to pure positional play, the technique being firstly to build up a position devoid of weaknesses, an ‘I can’t lose position,’ and secondly to create and take advantage of the minutest weaknesses in the opponent’s camp, a major weakness may show that imagination is not quite dead within.

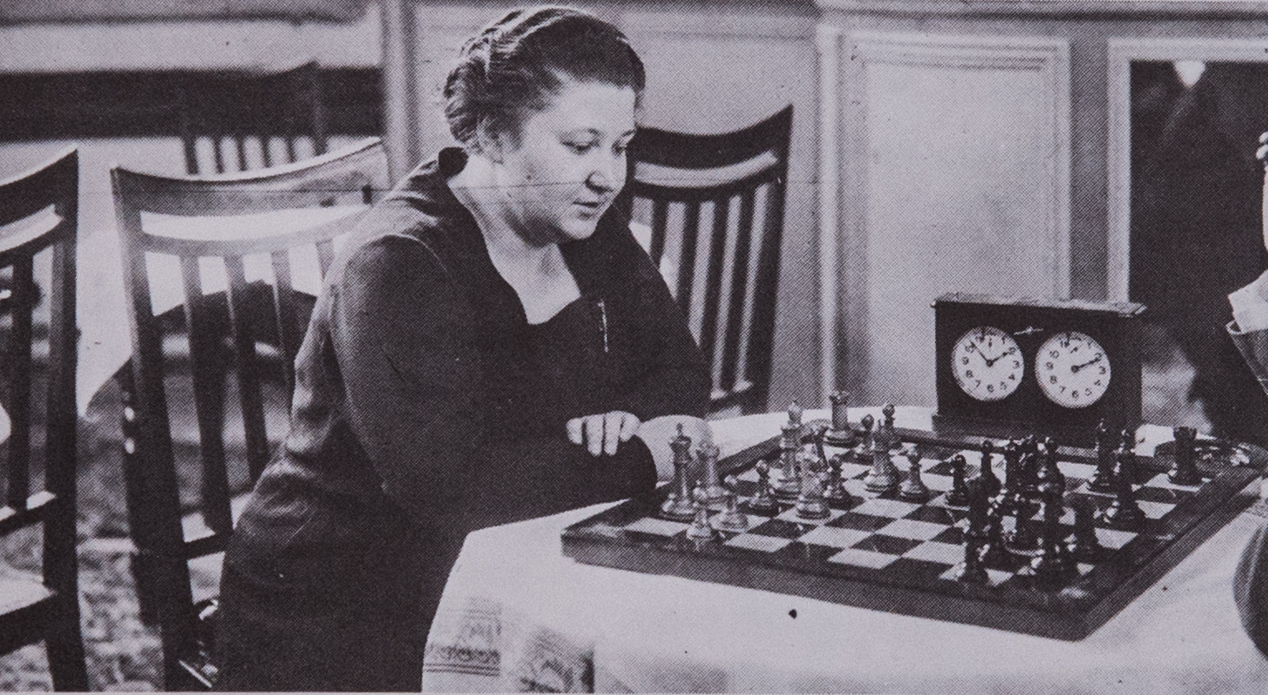

This defect in her play was the inevitable reflection of her character: sound common-sense, conscientious to an unusual degree, and persevering, while she had the combative, tenacious nature so desirable and so often found in good chess players; for chess is battle of wits, the fight is what most of use love in chess. Vera was, seldom assertive, a fault not uncommon in chess players. She sat placidly at the chess board, never causing even mild irritation by any of those nervous mannerisms that may always be seen in any chess room, the peripatetic fever being the most prominent. A slight flush would rise when the position grew difficult, or when she was short of time on her clock – and that was recurrent according to the time-limit.

Away from the chessboard show would readily talk of other subjects, and her great interest was in persons, in their actions and behaviour under the strain and stress of the unruly passions; in the moulding of their lives under the inscrutable dictates of chance; in the twists and turns of a mind warped perhaps by a casual incident long ago. Of course, she was a pagan, a thinking one, who had asked and asked and found only the answer that reasoning gave. She judged kindly and never inflicted upon others her own opinions or beliefs: she asked only that these should be heard as one side of any argument, for she enjoyed a dialectic bout.

A delightful side to her character was her simple sense of humour, and I remember so clearly her pleasure – glee would describe it more eloquently – when I gave her the punctuation necessary to make sense of that ludicrous collection of words, ‘Jones where Brown had had had had had had had had had had had the master’s approval’ Anyone who knew her only at the chessboard would have been astonished at the amount of bubbling merriment she discovered of of life’s events.

I shall remember her more for the woman as I knew her over many cups of coffee spread over many, many weeks – complacent, smiling, and kindly; conscientious, loyal, and sincere; as I understand the word, a Christian who would help any deserving person as best she could. E. G. R. C.

”

and here is the original article as printed:

BCM 1958 Appreciation by Peter Clarke

From British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXVIII (78, 1958), Number 7 (July), page 181 onwards) we have this retrospective from Peter Clarke:

“The night of June 27th,1944, Vera Menchik, World Woman Champion, was killed when an enemy bomb demolished her home in London; with her perished her mother and sister Olga. In these tragic circumstances the chess world lost its greatest woman player, still undefeated and at the height of her powers.

Vera Francevna Menchik was born in Moscow on February 16th, 1906, of an English mother and Czech father. There she spent her childhood, showing a love for literature, music, and, of course, chess, which at the age of nine she was taught by her father. She had a natural bent for the game and when only fourteen shared second and third places a schoolboys (!) tournament. The following year, 1921, the family came to England, where Miss Menchik lived the rest of her life.

As if by some fortunate coincidence, the Menchiks settled in Hastings, though it was not until the spring of 1923 that Vera joined the famous chess club. Her natural shyness and lack of knowledge of English caused this delay. However, they did not handicap her too much

as she herself afterwards wrote: ‘Chess is a quiet game and therefore the best hobby for a person who cannot speak the language.”

She studied the game eagerly, and very soon her talent caught the attention of the Hungarian grandmaster, Géza Maróczy, who was resident at Hastings at that time. Thus there began the most important period in her development as a player; a sound and mature understanding of positional play-and a thorough knowledge of a few special openings and defences: in particular the French Defence. The influence of

the grandmasters ideas was clearly apparent in her style throughout the whole of her career.

Miss Menchik’s rise to fame was meteoric: by 1925 she was undoubtedly the strongest player of her sex in the country, having twice defeated the Champion, E. Price, in short matches; and only two years later she won the first Women’s World Championship in London with the terrific score 10.5-0.5. She was just twenty-one, but already in a different class from any other woman in the world. For seventeen years until her death Vera Menchik reigned supreme in women’s chess, defending her world title successfully no less than seven times (including a match with Sonja Graf at Semmering in 1937, which Miss Menchik won 11.5-4.5. In the seven tournaments for the World Championship she played 83 games; winning 78, drawing 4, and losing 1 only! However, what was more remarkable was that she was accepted into the sphere of men’s chess as a master in her own right, a feat which no woman had done before or has done since. Up to then, women’s chess had been a very poor relation of the masculine game, but here was a woman who was a worthy opponent for the strongest masters.

Flohr wrote of her: ‘Vera Menchik was the first woman in the world who played chess strongly…who played like a man.’ It was as the ambassador extraordinary, so to speak, of the women’s game that Miss Menchik really made her greatest contribution to chess. Wherever she went, at home and abroad, she aroused great interest among her sex; others were eager to follow her, to identify themselves with her. Nowadays women’s chess is well organized, and much of the credit for this must go to Vera Menchik for first bringing it into the light. Among her many personal successes in international tournaments perhaps the greatest was at Ramsgate in 1929: as one of the foreign masters (she was still of Czech nationality) she shared second and third places with Rubinstein, * point behind Capablanca and above, among others, her tutor Maróczy.

Even the greatest masters recognized Miss Menchik’s ability; Alekhine himself, writing on the Carlsbad Tournament of 1929, said: ‘Vera Menchik is without doubt an exceptional phenomenon among women. She possesses great aptitude for the game…The chess

world must help her develop her talent!’

The Vera Menchik Club

An amusing incident occurred at this tournament. There were naturally sceptics among the masters over the lady’s participation. Flohr recalls how one of these, the Viennese master Becker, suggested:

‘Whoever loses to the Woman Champion will be accepted as a member of the Vera Menchik Club which I intend to organize.’

Becker was the first to lose to her, and that evening the masters chided him: “Professor Becker, you did not find it very difficult to join the club. You can be the Chairman.’ And forthwith he was chosen as Chairman for three years. Everyone wished that the new club would soon obtain more members! Indeed, the Vera Menchik Club has many famous names on its lists-Euwe, Reshevsky, Colle, Yates, Sultan Khan, Sir G. A. Thomas, Alexander, to mention a few.

In 1935 Miss Menchik returned to the country of her birth to take part in the great international tournament in Moscow. To be truthful, she had very little success, but she was everywhere treated with respect and sympathy by masters and spectators alike. The Soviet master l. Maiselis, writing in CHESS in 1944.(Shakhmaty za 1944 god), related the following entertaining anecdote from the tournament: One day a group of players and organizers were discussing the chances of Alekhine and Euwe in the forthcoming match. Flohr said: ‘It is quite clear that I will be World Champion.’ We looked at him inquiringly.

‘It’s very simple,” continued Flohr, ‘Euwe wins a match against Alekhine, Vera Menchik beats Euwe (at that time her score against Euwe was +2, =1, -1) and I will somehow beat Miss Menchik.’

We laughed at this good-natured joke, and we laughed all the more the next day when Flohr was unable, despite every effort, to defeat her in a vital game.

ln 1937 Miss Menchik married R. Stevenson, but in chess she continued to use her maiden name, made famous by so many victories. Her husband, a well-known organizer, became, Secretary of the B.C.F: in the following year and remained so until his death in 1943.

Since the days of Vera Menchik women’s chess has taken great strides forward; now there is a special committee of F.I.D.E. to look after its needs.- Only last year the first lnternational Women’s Team Tournament took place ln Emmen, Holland; the new World Champions, the U.S.S.R., became the first holders of the Vera Menchik Cup. So chess goes onwards, but the name of its first Queen will ever be remembered.”

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Robert Hale, 1970 & 1976) by Anne Sunnucks :

“Woman World Champion from 1927 to 1944. Vera Menchik was born in Moscow on 16th February 1906 of an English mother and a Czech father. Her father taught her to play chess when she was 9.

In 192l her family came to England and settled in Hastings (at 13, St. John’s Road, St. Leonards-on-Sea, TN37 6HP) :

Two years later, when she was 17, Vera joined Hastings Chess Club,

where she became a pupil of Geza Maroczy. The first Women’s World Championship was held in 1927. Vera Menchik won with a score of 10.5 out of 11. She defended her title successfully in Hamburg in 1930, in Prague in 1931, in Folkestone in 1933, in Warsaw in 1935, in Stockholm in 1937 and in Buenos Aires in 1939. She played 2 matches against Sonja Graf, her nearest rival, in 1934 when she won +3 -1 and in 1937, in a match for her title when she won +9 -1 =5.

The first woman ever to play in the British Championship and the first to play in a master tournament, Vera Menchik made her debut in master chess at Scarborough 1928 when she scored 50 per cent. The following year she played in Paris and Carlsbad, and it was at Carlsbad that the famous Menchik Club was formed. The invitation to Vera Menchik to compete among such players as Capablanca, Euwe, Tartakower and Nimzowitch was received with amusement by many of the masters. The Viennese master, Becker was particularly scornful, and in the presence of a number of the competitors he suggested that anyone who lost to Vera Menchik should be granted membership of the Menchik Club. He himself became the first member. Other famous players who later joined the club were Euwe, Reshevsky, Sultan Khan, Sir George Thomas, C. H. O’D. Alexander, Colle and Yates.

Her greatest success in international tournaments was at Ramsgate in 1929, when she was =2nd with Rubinstein, half a point behind Capablanca and ahead of Maroczy. In 1934 she was 3rd at Maribor, ahead of Spielmann and Vidmar. In 1942 she won a match against Mieses +4 -l -5. In 1937 Vera Menchik married R. H. S. Stevenson, who later became Hon. Secretary of the British Chess Federation. He died in 1943. She continued to use her maiden name when playing chess. On her marriage she became a British subject.

From 1941 until her death she was Games Editor of CHESS. She also gave chess lessons and managed the National Chess Centre, which opened in 1939 at John Lewis’s in Oxford Street, London and was destroyed by a bomb in 1940.

In 1944 Vera Menchik was a solid positional player, who avoided complications and aimed at achieving a favourable endgame. Her placid temperament was ideal for tournament play. Her main weakness was possibly lack of imagination. Her results have made her the most successful woman player ever.”

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess, (BT Batsford, 1977) by Harry Golombek :

Probably the strongest woman player in the history of the game, Vera Menchik was born in Moscow and, though her father was a Czechoslovak and her mother English, she played for most of her

life under English colours.

In l92l her family came to Hastings in England and there Vera became a pupil of the great Hungarian master, Geza Maroczy. This was to have a dominating influence on her style of play which was solidly classical, logical and technically most well equipped. Such a style enabled her to deal severely not only with her fellow women players but also with contemporary masters and budding masters. Vera did extremely well, for example, against C. H. O’D. Alexander

and P. S. Milner-Barry, but lost repeatedly to H. Golombek who was able to take advantage of her lack of imagination by the use of more modern methods.

Vera was soon predominent in women’s chess. In the first Women’s World Championship tournament, at London in 1927, she won the title with a score of 10.5 out of 11 and retained the championship with great ease at all the subsequent Olympiads (or International Team tournaments as they were then known more correctly) at Hamburg 1930, Prague 1931, Folkestone 1933, Warsaw 1935, Stockholm 1937 and Buenos Aires 1939.

With Sonja Graf, the player who came nearest to her in strength among her female contemporaries, she played two matches and demonstrated her undoubted superiority by beating her in 1934 (+3-l) and again in a match for the title in l937 (+9-l=5).

In 1937 Vera officially became a British citizen by marrying the then Kent and later B.C.F. Secretary, R. H. S. Stevenson (Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson: ed).

(Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson was home news editor of the British Chess Magazine, secretary of the Southern Counties Chess Union and match captain of the Kent County Chess Association).

Oddly enough, Sonja Graf, many years later, also became a Mrs Stevenson by marrying an American of that name some years after the Second World War.

Vera Menchik also played and held her own in men’s tournaments. She did well in the British championship and her best performance in international chess was =2nd with Rubinstein in the Ramsgate Team Practice tournament ahead of her old teacher, Maroczy. She also had an excellent result at Maribor in 1934 where she came 3rd, ahead of Spielmann and Vidmar.

Her husband died in 1943 and Vera herself, together with her younger sister Olga and her mother, was killed by a V1 bomb that descended on the Stevenson home in London in 1944.

This was a sad and premature loss, not only for British but for world chess, since there is no doubt she would have continued to dominate the female scene for many years.

As a person Vera was a delightful companion, jolly and full of fun and understanding. As a player she was not only strong but also absolutely correct and without any prima donna behaviour. Generous in defeat and modest in victory, she set a great example to all her contemporaries.

An example of Vera’s attacking play at its best against her nearest rival, Sonja Graf, is shown by the following game which was played in her 1937 match at Semmering in Austria :

From The Oxford Companion to Chess, (Oxford University Press, 1984) by Hooper and Whyld :

“Woman World Champion from 1927 until her death. Daughter of a Czech father and an English mother, Menchik was born in Moscow, learned chess when she was nine, settled in England around

1921, and took lessons from Maroczy a year or so later. In 1927 FIDE organized both the first Olympiad and the first world championship tournament for women. These events were run concurrently, except in 1928, until the Second World War began, and Menchik won the women’s tournament every time; London 1927 (+10=1); Hamburg 1930 (+6=1 — 1); Prague 1931 (+8);

Folkestone 1933 ( + 14); Warsaw 1935 (+9); Stockholm 1937 (+14); and Buenos Aires 1939 ( + 17=2). She played in her first championship tournament as a Russian, the next five as a Czech,

and the last as a Briton. She also won on two matches against her chief rival, the German-born Sonja Graf (c. 1912-65): Rotterdam, 1934 (+3-1), and Semmering, 1937 (+9=5—2),

In international tournaments which did not exclude men Menchik made little impression; one of her best results was at Maribor 1934 (about category 4) when she took third place alter Pirc and L. Steiner ahead of Spielmann. In 1937 she married the English chess organizer Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson (1878-1943), A chess professional, she gave lessons, lectures, and displays, and was appointed manager of the short-lived National Chess Centre in 1939. In 1942 she defeated Mieses in match play (+4=5-1), She, her younger sister Olga (also a player), and their mother were killed in a bombing raid.

Her style was positional and she had a sound understanding of the endgame. On occasion she defeated in tournament play some of the greatest masters, notably Euwe, Reshevsky, and Sultan Khan. Men she defeated were said to belong to the Menchik club. When world team championships for women (women’s chess Olympiads) were commenced in 1957 the trophy for the winning team was called the Vera Menchik Cup.”

BCM 1994 Appreciation by Bernard Cafferty

From British Chess Magazine, Volume CXIV (114, 1994), Number 8 (August), page 424 onwards) we have this retrospective from Bernard Cafferty:

Fifty yezus ago the chess world was tragically robbed of its most talented female representative of the first half of this century. A Vl rocket (ed: The V1 was not a rocket but a flying bomb) fell on a house in Gauden Road, Clapham, London, that was the residence of Russian-born Vera Menchik, her younger sister and their mother. The trio were sheltering in the cellar, as they usually did during the Nazi air raids on London. The house was completely destroyed. The air-raid shelter in the garden was all that was left.

Vera Menchik was born in Moscow on 16 February 1906, and died on 26 June 1944. The date of death is usually given as 27 June, but Ken Whyld has seen the death certificate and tells us the tragedy occurred before midnight, not after.

The young Vera grew up in a cosmopolitan family in Moscow, where her Czech father and English mother lived in a six-room flat, which they had to share, after 1917, with families from ‘the lower depths’ (the name of a famous play by Gorky which could also be translated as ‘on Skid Row’). In autumn 1921 the family left Soviet Russia and came

to England where they lived in Hastings.

Botvinnik recalls that he visited the Menchik household in Hastings in 1935, where he met Vera’s grandmother. Then, in 1936, he visited the other house in London, after the Nottingham 1936 tournament. At that time the Soviet Embassy arranged a reception in an attempt to counter the awful image of a country deep in the throes of the show trials and widespread repression. However, only Botvinnik, Menchik, Capablanca and Lasker turned up.

Vera Menchik was taught the moves of chess by her father, Franz, when she was nine years old. However, she only took the game seriously from the age of 17, when she joined the Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club, which at that time had its famous extensive sea-front premises near the pier.

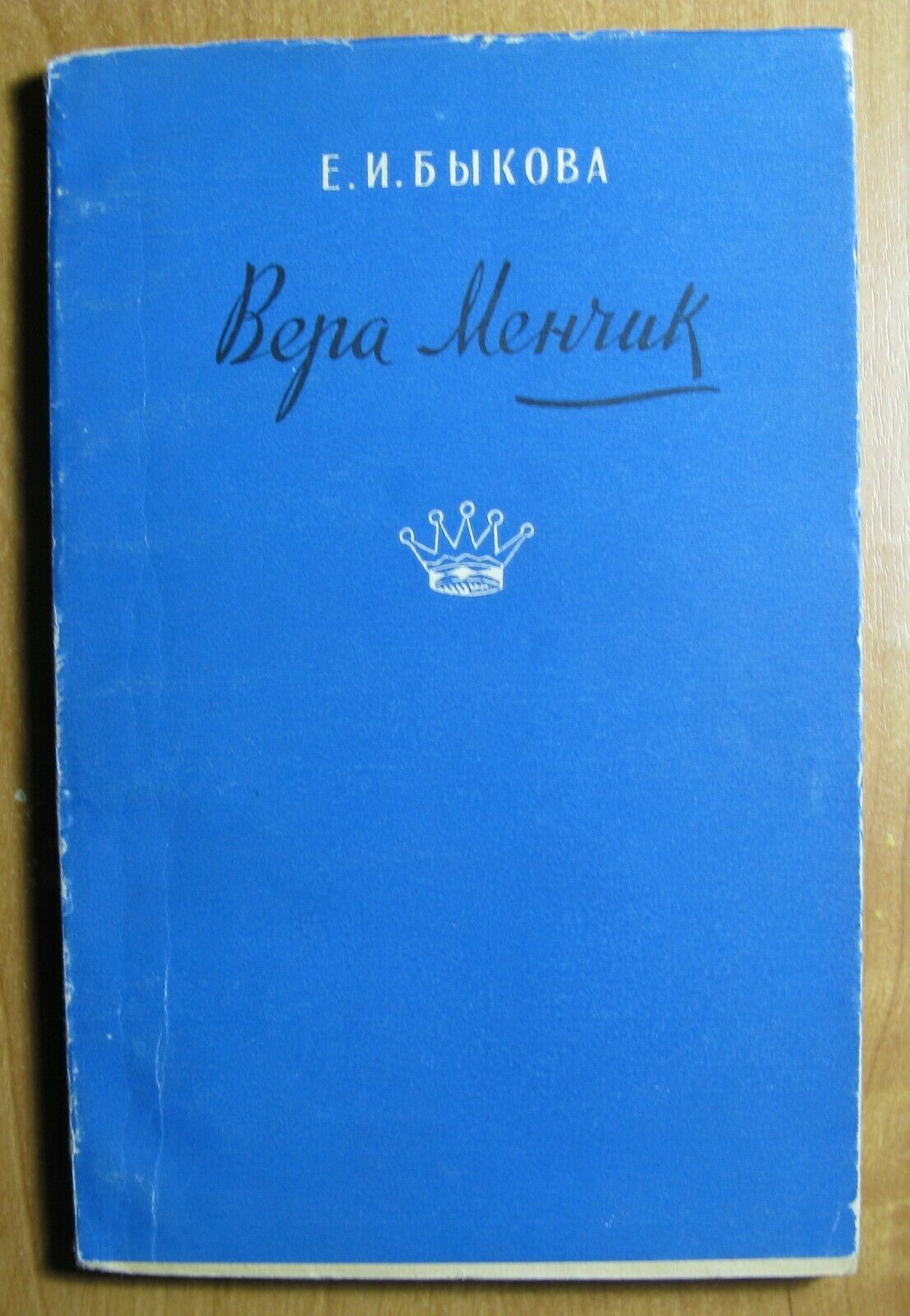

According to the 1957 book in Russian by Bykova, on which this account is largely based, Vera only knew Russian when she cam to England, and one of the reasons for her to join the chess club was that a fluent knowledge of English was not necessary for her to be able to benefit from such a silent activity as chess.

The young Vera was fortunate in that the Hungarian grandmaster, Géza Maróczy, had a professional engagement with the Hastings club at this time, and the young lady became his most famous pupil. Her sound style with no fear of long endgames was a mirror of her mentor. She was also helped by Professor JAJ Drewitt, another Hastings club member, in the study of openings, particularly the closed openings.

Vera was initially counted as a Russian and did not enter the British Women’s Championship at the traditional August BCF Congress. However, she made her debut in international chess at a lower section of the 1923-24 Hastings Congress. In 1925 she beat the leading English player Edith Price by a score of +5 =2 -3 in two private matches. She duly took part in the Hastings Congresses, year after year. In the 1926-27 event she scored her first big success by sharing first place with the young Milner-Barry on 6.5(9) in the Premier Reserves.

By 1927, VM was ready to enter the first Women’s World Championship, which was played at the 4th FIDE Congress, alongside the Olympiad in London. She conceded only one draw in her eleven games and so took the title which she was to retain with ease from that day, when she was just 21, till her death 17 years later. In her first title attempt, she

was counted as a Russian, but at the next five (at the Hamburg 1930, Prague 1931,

Folkestone 1933, Warsaw 1935 and Stockholm 1937 Olympiads) she played as a representative of Czechoslovakia. It was only after her marriage to the prominent English organiser R. H. S. Stevenson in 1937 that she was counted as British and played under the Union Flag in her last title defence at Buenos Aires 1939.

Her dominance can be gauged from the fact that she won all eight games at Prague, all 14 at Folkestone, all 9 at Warsaw, all 14 at Stockholm and conceded just two draws in 19 games in 1939. The most serious challenge came in a title match at Semmering-Baden with Sonja Graf, then of Germany. Here too it was largely one-sided: +9 =5 -2.

She made her debut against male masters in an international tournament at Scarborough in 1928, finishing equal 7-8 in a field of 10, but in only the following year, at the Kent Easter Congress, she had one of her best results.

It was decided to run a Scheveningen tournament at Ramsgate with seven foreign masters pitted against seven home representatives. As was only to be expected, Capablanca came top of the ‘external examiners’, yet the next placing was a sensation: Capablanca 5.5(7) followed by Miss Menchik and Rubinstein 5, Koltanowski and Maroczy 4.5, Soultanbeieff 4 and Znosko-Borovsky 3. Sir George Thomas, whom Menchik beat, scored 3 to head the English team of Yates, Winter, Michel, Tylor and E. G. Sergeant.

Naturally enough, after this it was inevitable that foreign invitations should follow. Later in 1929 the young ‘Russian’ took part in a Paris tournament and then in the great Carlsbad tournament, the last of a wonderful series. Her presence here created some scepticism, and on the eve of the first round the Austrian theoretician Becker suggested that a Vera Menchik club be formed, membership of which would be granted only to those who lost to the lady. According to Flohr, there was an expectation that it would be a small select club, but Becker was quickly proved wrong for he became its first member in the third round! His only consolation was that the club proved far more extensive and democratic as the years rolled by. In fact the club came to include grandmasters such as Euwe (who earned a two-fold qualification) Sultan Khan and Reshevsky as well as masters such as Saemisch, Colle, Golombek, Sir George Thomas, Alexander…

However, Miss Menchik could not make much of the universally strong opposition and made only three points out of 20, finishing last, three points behind Sir George Thomas. With further experience she was to have more impressive results, such as her 8th place at London 1932, won by Alekhine, where she came ahead of Milner-Barry, Sir George, Burger and Winter.

A high spot of the 1930s for Vera was her participation in the 1935 Moscow tournament, but her return to her native city was so taken up with social engagements that she was unable to give of her best, and she scored only one and a half points from 19 games though she did take a draw off the winner of second prize, Flohr.

Vera had to eke out a living from teaching chess, adjudications and simultaneous exhibitions. After her return from Buenos Aires she lived in London. She was appointed administrator of the new National Chess Centre at John Lewis’s store in Oxford Street, which, alas, was destroyed by enemy action in 1940.

Her last great success was a match with the veteran GM, Jacques Mieses who was a refugee from anti-Semitic German. Played in 1942, the result was +4 =5 -1.

In 1943 Vera’s husband died. In 1944 she was playing in the championship of the West London Club, a strong event which included Sir George Thomas, PM List, EG Sergeant and Mieses amongst the players. Doubtless she was looking forward to the resumption of International chess activity after the war. It was not to be. We live in an age when the achievements of women players such as Gaprindashvili, Chirburdanidze, Xie Jun and the Polgar sisters have built on the pioneer work of Vera Menchik. Yet the path of the pioneer is always the hardest.

Finally, by all accounts of contemporaries, Vera was a cultured and sympathetic person who never gave cause for offence amongst the many players she met. Had she lived, she would have continued to be a jewel in the crown of British chess, which had to drag itself up from the boot straps after the devastation of war. What a tragic loss.

She was inducted to the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2011. The Women’s Olympiad trophy is known as the Vera Menchik Cup in her honor. The fifth FIDE Vera Menchik Memorial Tournament was held in 2022.

The Caplin Menchik Memorial ran from Saturday 18th to Sunday 26th June 2022 (games started 14:00 BST) at the MindSports Centre, Dalling Road, London W6 0JD. The format was 10-player all-play-all, one game per day, WIM & WGM norm opportunities were made available.

Other Articles

Here is an excellent article from the Hastings and St. Leonard’s Club written by Brian Denman.

Here is an excellent article from Neil Blackburn (aka SimaginFan) on chess.com

Here is an excellent article by Albert Whitwood

Here is her Wikipedia entry.

Here is an excellent record compiled by Bill Wall.

Biography of Vera Menchik British chess player

Edward Winter was less than impressed with the above book.