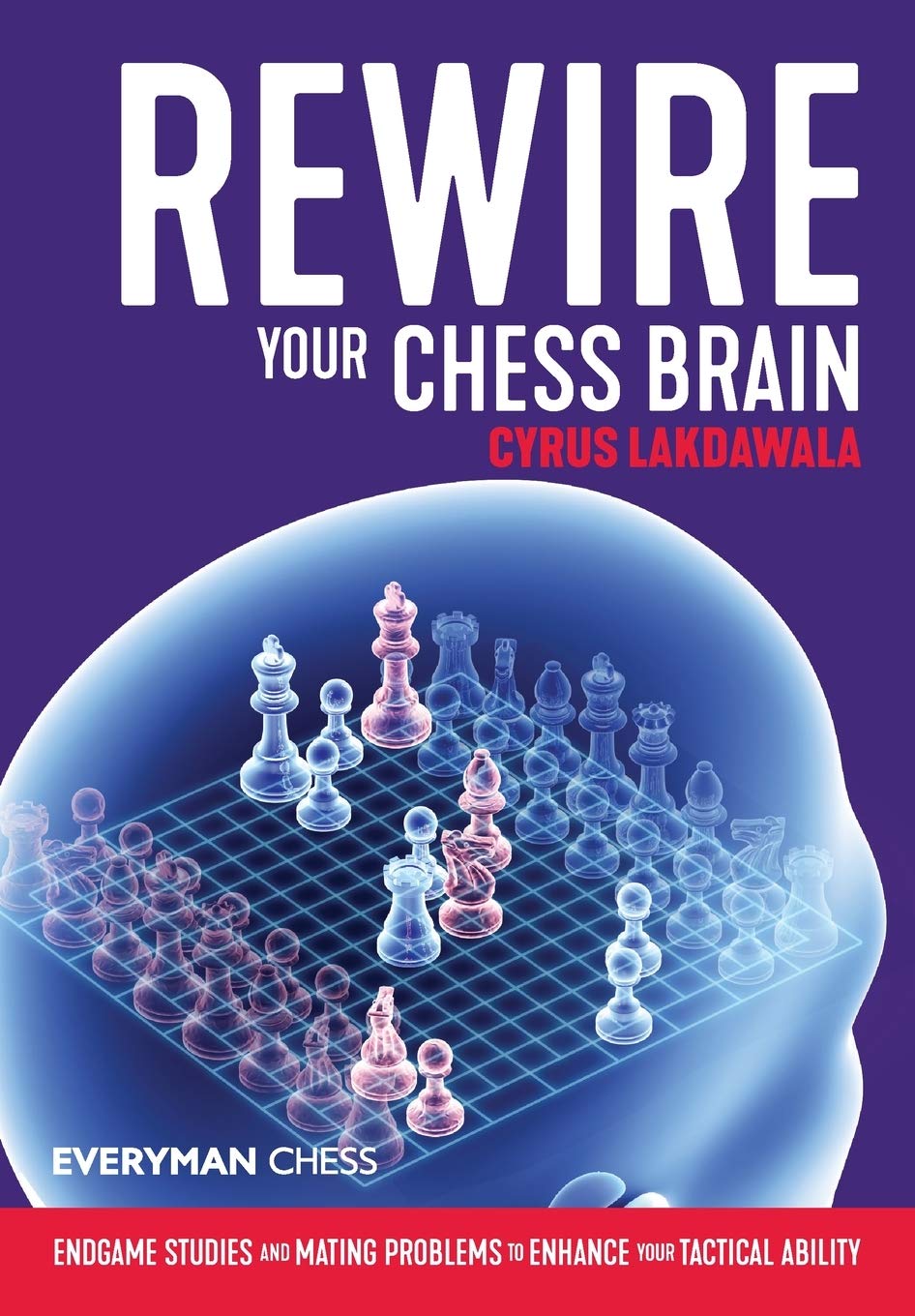

Cyrus Lakdawala is an IM and former US Open Champion who teaches chess and has written over 25 books on chess openings.

The ever prolific Cyrus Lakdawala’s latest book offers a collection of endgame studies and problems aimed primarily at players who are not all that familiar with the world of chess compositions.

Much of the material is taken from the Facebook group Chess Endgame Studies and Compositions which Lakdawala runs with Australian GM Max Illingworth. I should declare an interest here as I’m a member of, and a very occasional contributor to, this group.

The first half of the book introduces the reader to the world of endgame studies. After a brief preliminary chapter taking us on a journey of almost a thousand years up to 1750 (though I’m not sure how Al Adli was composing in both 800 and 900), we move onto a collection of studies with the stipulation ‘White to play and draw’. Like this one (the solutions are at the end of the review).

Frédéric Lazard L’Échiquier de Paris 1949

(Lazard’s first name is anglicized to Frederick in the book. He died in 1948: perhaps this was first published in a posthumous tribute.)

The next, and longest, chapter is, you won’t be surprised to hear, devoted to ‘White to play and win’ studies.

Another short example:

Mikhail Platov Shakhmaty 1925

Then we move on from studies to problems. After a brief excursion to Mates in 1 in Chapter 4, Chapter 5 deals with mates in 2, like this one from the ever popular Fritz Giegold.

Fritz Emil Giegold Kölnische Rundschau 1967

(The first word of the newspaper is given as Kolner, without an umlaut: Wikipedia tells me the correct name.)

Another composer to feature heavily in this book is the great Puzzle King himself: Sam Loyd. Here’s an example from Chapter 6: Mates in Three Moves.

Sam Loyd Cleveland Voice 1879

Chapter 7 brings us some mates in four or more moves. Chapter 8 looks at some eccentric problems, Chapter 9 looks at study like themes in real games (yes, Topalov-Shirov, as you probably guessed, is there), and finally Chapter 10 presents us with some studies composed by young American IM Christopher Yoo.

On a personal level, I’d have liked some helpmates, which are often very attractive to practical players, and perhaps also problems with other stipulations: serieshelpmates or selfmates, for example. A short introduction to fairy pieces and conditions would also have been interesting. Something for a sequel, perhaps?

Cyrus Lakdawala has a large and devoted following, and his fans will certainly want this book. Those who don’t like his style will stay well clear. As for me, I find Everyman Cyrus a far more congenial companion than NiC Cyrus: do I detect a firmer editorial hand in removing some of the author’s more fanciful analogies? Given the nature of the book I think it works quite well: entertaining positions can take ‘entertaining’ writing but more serious material demands more serious writing.

The studies and problems are well chosen to be attractive to the keen over the board player who is not very familiar with the world of chess compositions. If you don’t know a lot about this aspect of chess and, perhaps enjoying the examples in this review, would like to investigate further, this book would be a good place to start.

The current Zeitgeist seems to demand that chess books are marketed as being good for you rather than just enjoyable and entertaining, and here it’s claimed that solving the puzzles in this book will ‘without question, undoubtedly improve the ‘real world’ tactical ability of anyone attempting to do so. Well, possibly. Solving endgame studies has been considered by many, Dvoretsky for one, to be beneficial for stronger players, and I quite understand why. I’m less convinced, though, that solving problems is the most effective way to improve your tactical skills, but it may well give you an increased appreciation of the beauty that is possible over 64 squares, and inspire you to find beautiful moves yourself.

My issue with the book concerns lack of accuracy, particularly in the problem sources. Puzzle 190 was composed by (the fairly well known) Henry D’Oyly Bernard, not by (the totally unknown) Bernard D’Oily. Frustratingly for me, I seem to remember pointing this out to the author on Facebook. Puzzle 242, a much anthologised #3 by Kipping, is given as ‘Unknown source 1911’. It took me 30 seconds (I know where to look) to ascertain that it was first published in the Manchester City News. As Fritz Giegold was born in 1903, it seems unlikely that he was precocious enough to compose Puzzle 237 in 1880. Again, a quick check tells me it was actually published in 1961. And so it goes on.

It’s not just the sources: the final position of puzzle 203 has three, not four pins. Someone with more knowledge of chess problems might have pointed out that in Puzzle 164 Sam Loyd displays an early example of the Organ Pipes Theme.

Even the back cover, which you can see below, is remiss, in claiming that ‘In a chess puzzle, White has to force mate in a stipulated number of moves’. No – you mean ‘chess problem’, not ‘chess puzzle’.

Chess problem and study enthusiasts are, by their nature, very much concerned with accuracy. It’s unfortunate that this book doesn’t meet the high standards they’d expect.

To summarise, then: this is a highly entertaining book which will appeal to many players of all levels, especially those who’d like to find out more about studies and problems. It’s somewhat marred by the unacceptable number of mistakes, which might have been avoided with a bit of fact checking and a thorough run through by an expert in the field of chess composition.

(Apologies for the repeated diagrams in the solutions: it’s a function of the plug-in used by British Chess News.)

Richard James, Twickenham 7th January 2021

Book Details :

- Paperback : 530 pages

- Publisher:Everyman Chess (31 August. 2020)

- Language:English

- ISBN-10:1781945691

- ISBN-13:978-1781945698

- Product Dimensions: 17.45 x 2.97 x 24.08 cm

Official web site of Everyman Chess